JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

|

Ukiyo-e Prints 浮世絵版画 |

| Port Townsend, Washington |

|

ASHIYUKI 芦幸 あしゆき |

|

|

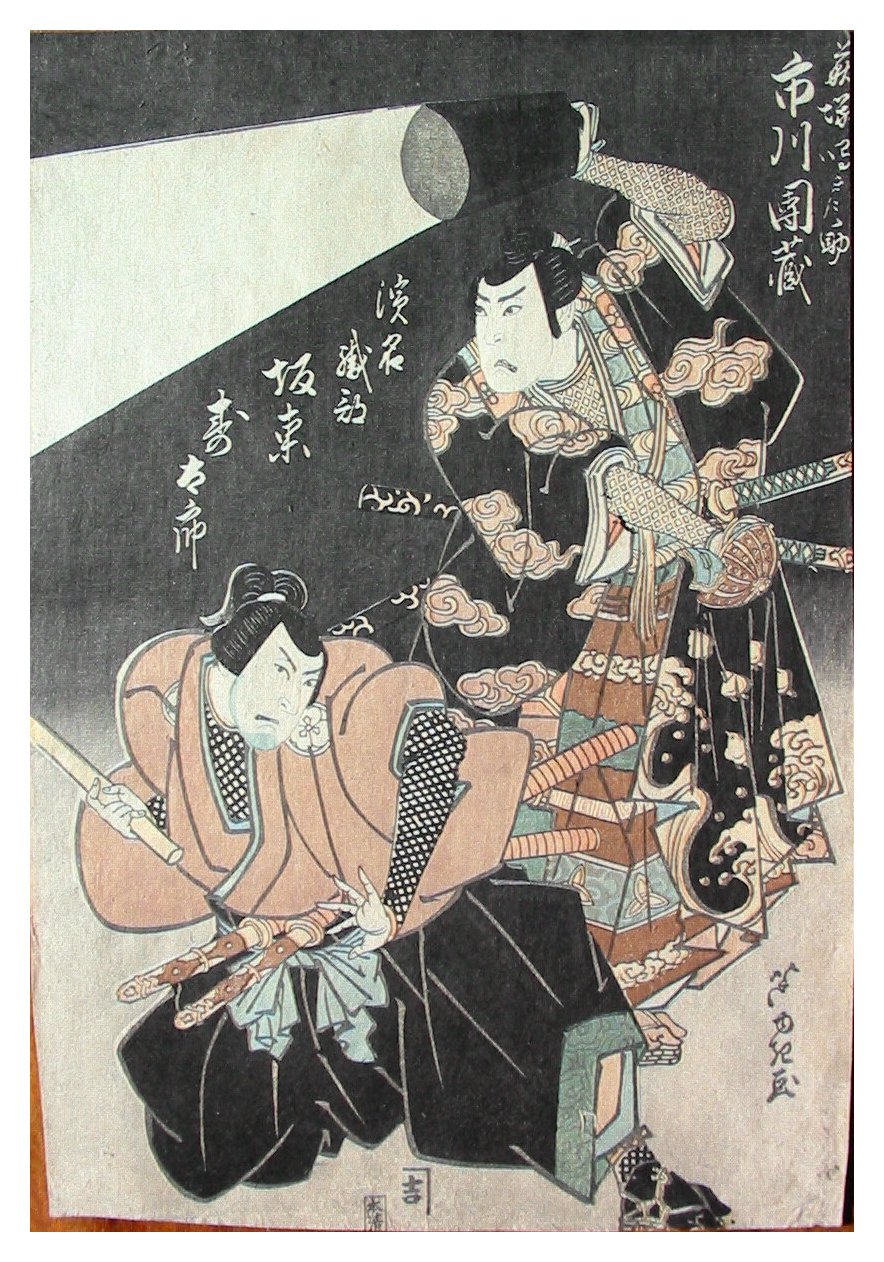

Actor on the Right: Ichikawa Danzō V as Hagizuka Narutonosuke |

|

|

市川団藏 いちかわ.だんぞう |

萩塚鳴戸之助 はぎづか.なるとのすけ |

|

Actor on the Left: Bandō Jutarō I as Hamana Oribe |

|

|

坂東寿太郎 ばんど.じゅたろう |

浜名織部 はまな.おりべ |

|

Play: Momochidori Naruto no Shiranami 百千鳥鳴門白浪 ももちどり.なると.の.しらなみ |

|

|

Size: 14 7/8" x 10" |

|

|

Date: 1825, 1st Month Bunsei 8 文政8年 |

|

|

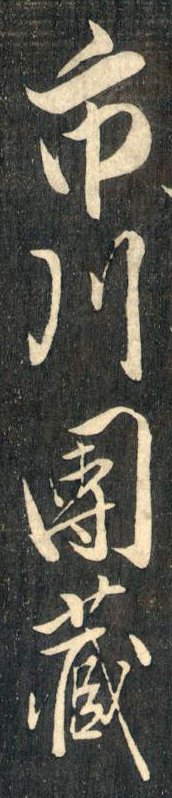

Publishers: Kichi (the upper right) and Honsei (Honya Seishichi)

|

|

|

吉 きち |

夲清 ほんせい |

|

Signature: Ashiyuki ga

|

|

| There is a copy of the full triptych at the Hankyu Culture Foundation. | |

|

$185.00 SOLD! |

|

This print featured above is the

right hand panel of a triptych.

| The full set is shown below, but is NOT for sale. | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|||

| We are displaying it here simply for your information. | ||||||

| I JUST REALIZED! |

|

|

The first word of the title to this play in Japanese transliterates as Momochidori (百千鳥). One translation of this term could mean "100 chidori". The word "chidori" is often translated as plover or snipe. This bird is frequently paired with images of dramatic waves and that is what is used to decorate the outer robes of the standing figure. According to Merrily Baird on page 103 of her Symbols of Japan "...the chidori is an auspicious symbol for the warrior class. The first ideograph used to write the word means 'one thousand,' and the second is a homophone for the words 'seize' and 'capture.' Because the bird overcomes high waves and winds to migrate, it is seen as an emblem of perseverance and the conquering of obstacles." |

|

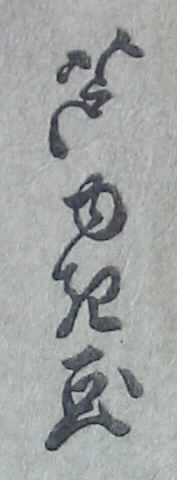

WHAT DOES THIS CREST

TELL US?

IT HELPS US TO IDENTIFY THE ACTOR! |

|

|

|

Every culture I know of uses symbols not only as talismans or markers for class distinctions, but also just for easy identification. Sports teams wear different colors and one can easily find oneself in the stands among a sea of orange coated boosters fanatically screaming for victory for their side. Crusaders followed the sign of the cross, Muslims the crescent moon. Medieval knights had their colors and heraldic escutcheons. Napoleon resurrected the ancient image of the bee. And modern pan-national societies have used everything from the hammer and sickle to such symbols of capitalist consumption as the Louis Vuitton logo. The problem with the Vuitton and other logos is that they are so often counterfeited. We are surrounded by symbols. In fact, we are awash in them.

Japanese culture is no different. It has followed similar patterns from the ancient use of talismanic devices to clan crests to actors mons to modern logos.* That is why the crest featured above is significant. It was a marker which quickly identified to those in the know the name of that particular actor, Ichikawa Danzô V. But there should be a cautionary note for the modern viewer ignorant of how to read each little element: The clothing of the performer might display a lot more than just the actor's crest. There might even be other crests in near proximity. In fact, the clothing offers many different clues as to who is being portrayed or some great literary allusion, etc., and most of which still alludes the majority of us. [See the section called "I Just Realized!" further up this page.] |

|

|

|

*When I was little I noticed the visceral reaction and repulsion toward the German swastika long before I knew anything about the Nazis. Then once I did learn the history of that period I began to share the abhorrence of my contemporaries. But such a reaction can also be blinding and a cause of great ignorance and naiveté. The Germans had borrowed the swastika from their other distant relatives among the Indo-Europeans. That symbol was in use thousands of years before Hitler chose it for his own. To counter that argument modern individuals like to say things like "The arms of the Nazi swastika go one way and the ancient ones the other." This is not true, but it is almost impossible to shake people from their beliefs. Ask anyone in the West who is not already versed in ukiyo-e art what kind of paper the Japanese printed on and they almost to a person say "Rice paper." Again they are wrong, but just try to tell them that.

The ancient swastika which was called the manji in Japan originally did not carry the baggage which weighs down the post 1945 Nazi totem. In fact, it had a much more positive aspect because of its identification with Buddhism. Nevertheless, in the 19th century in Japan there were Shinto purists who railed against such foreign based imagery and this set off a wave of native iconoclasts hell-bent on destroying the manji and so much more. We saw the same thing happen during the Reformation in Europe when the Dutch stormed the Catholic churches and destroyed the statuaries and paintings. We saw this again in Afghanistan at Bamiyan in early 2001 when the Taliban decided to blow up enormous sculptures of Buddha. The choice of the World Trade Center buildings represented something grotesquely symbolic to their enemies. The world was helpless to prevent it. Such is the way of the world. It will happen again...and again...and again. Such is the power of the symbol. |

|

FIVE SURE-FIRE WAYS TO FIND OUT WHO THE ACTOR IS IN ONE OF YOUR PRINTS!

DISCLAIMER: WELL SORT OF... |

|

|

|

THE CREST OR MON

もん |

|

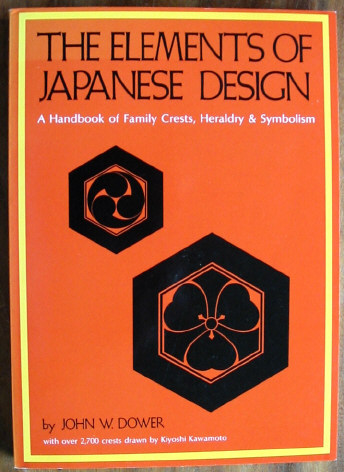

There are Japanese volumes of illustrations that show mon after mon after mon. These represent the crests specific to each family or to individuals or groups of actors. Unfortunately, there is not that much compiled in English that I am aware of and one has to search through several sources in the hope that they will find just exactly what they are looking for.. |

|

|

|

John Dower's book shown above is an excellent guide to the breadth and inventiveness of Japanese design motifs used for mons. "...with over 2,700 crests drawn by Kiyoshi Kawamoto" there is no finer compendium of its type which I know of in English. While it is not particularly helpful in the identification of which mon goes with which actor it is remarkable in its scope and basic details. Well organized, it illustrates everything from stylized radishes to feathers and everything else in between. It would be a good addition to anyone's library who is interested in researching these crests. Because it is so basic it will not tell you everything you want to know. However, all in all, I would recommend it highly. |

|

|

|

PORTRAIT-QUALITY LIKENESS

NIGAO 似顔 にがお |

|

According to Donald Jenkins Katsukawa Shunshō (1726-92) was the first Japanese print artist with a "...skill in capturing likenesses." This Jenkins says is "...undoubtedly most important [aspect]...for a designer of actor prints. None of his contemporaries could touch him in this regard...and it is hard to think of any later print artist who could equal him. Shunshō's abilities as a portraitist must have seemed all the more remarkable in that no such portrayals had ever been attempted in the actor print genre before." (1)

Roger Keyes in his catalogue of the Ainsworth Collection said that "Utamaro may have been the first artist to apply ideas of physiognomy..." (2) I am not sure that this contradicts what Jenkins said about Shunshō since Webster's Dictionary defines physiognomy as "the facial features held to show qualities of mind or character by their configuration or expression." One artist captured the look and the other captured the causes which give us that look.

Prior to Shunshō the only way a person could tell which actor was being portrayed was 1) the prominent display of the actor's crest or 2) kanji text which spelled it out for them or 3) having seen in person the performance for which this print was created as a memento.

When I was a youngster and went to major league baseball games one of the first things I learned was "You can't know the players without a program." In general, the same principal works for the identification of actors in Japanese prints.

The caricature used in profile above is by Kuniyoshi. |

|

|

|

1. The Actor's Image: Print Makers of the Katsukawa School, by Timothy Clark and Osamu Ueda with an essay by Donald Jenkins, Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 19. 2. Japanese Woodblock Prints: A Catalogue of the Mary A. Ainsworth Collection, distributed by Indiana University Press, Roger Keyes, 1984, p. 36. |

|

|

|

TEXT IN KANJI

|

|

|

|

|

|

BOOK, CATALOGUE OR ON-LINE COLLECTION |

|

Just because a print you own is illustrated in a book or on-line does not make yours authentic. On the other hand it doesn't make the example you are looking at authentic either. The odds are greater that a print is the real McCoy if it appears in a book by a credible author or in a catalogue from a reputable museum exhibition. The problems: There are lots of copies and forgeries out there. (For some interesting information about art forgeries and fakes take a look at the June 2005 issue of "Art News". These articles are not about Japanese prints, but they do provide a lot of information about the problem of fraud in general.)

I have a reasonably large resource library on Japanese prints and culture and use it all of the time. It has been invaluable when I am doing research: Titles, artists, editions, publishers, iconography, dates, etc. Handling large numbers of authentic prints is the best learning process. In time it becomes rather easy to make the determination between a fake and an original. Unfortunately everything else in between falls into those ubiquitous shades of gray. |

|

|

|

ASK AN EXPERT |

|

This is an obvious route which can be taken. But here too there should be a cautionary note or two or three. Many of the so-called experts speak from the mountain top. I suppose they have to because they don't want to be seen equivocating. Makes them look weak or wrong or both. However, they aren't always right. They might think they are and you might think they are, but that doesn't make it so. Remember Newton was right until Einstein came along. Of course, Newton was no slacker, but...

It doesn't hurt to get a second opinion. Somewhat like visiting a doctor you aren't too sure of. But be prepared to pay for their services. They don't all charge and don't all charge for the same types of advice/opinions. The second opinion could be your own research. Check their facts if you can even if you feel the field is too daunting. Relax, breath deeply and try to find corroboration. Experts often don't agree and everybody is wrong sometimes.

There are a lot of very cheap people out there --- you know who you are --- or, at least, you should know --- who are forever looking for free advice. Why pay when you can get it for free? Right! Well, you get what you pay for. And yet even when you do pay sometimes you get led astray. It's a crapshoot. |

|

|

|

WHY ARE THERE TWO PUBLISHERS' SEALS ON THIS PRINT?

To be perfectly candid we don't know why. This issue came up again recently --- today is May 8, 2005 --- when one of our correspondent/contributors, E, wrote to us to point out that Roger Keyes and Keiko Mizushima in their The Theatrical World of Osaka Prints mentioned in the back of the catalogue in a section entitled "Concordance of Names" that the Honsei (夲清 or ほんせい) seal appeared with that of numerous other smaller publishing houses and specifically with that of Kichi (吉 or きち) from 1823-33. (1) Our print featured on this page with both of these seals was issued toward the beginning of this period, i.e., 1825. Kichi, on the other hand, is only shown as working with two different publishers and both of these may have been Honsei using alternate names.

Dean J. Schwaab helps to clear up the two publishers issue, but only somewhat. In the end he doesn't really tells us how or why this happened. He tells us that the production of actor prints in the Osaka/Kyōto area had a long tradition and that in time the local publishers came to specialize almost exclusively in kabuki themes. Unlike Edo where publishers sprouted up everywhere something prevented similar entrepreneurial growth in Osaka. The publisher Shiochō seems to have a strangle hold on the production of Edo-style oban prints from their inception in ca. 1812. But then in 1816 "...four publishers succeeded in breaking that monopoly..." (2) They were Tenki, Wataki, Honsei and Toshin. "They in turn, either by governmental restriction on licenses or through collusion, managed to keep out further competition until the late 1830s." (3)

"This is not to say that the seals of a group of minor publishers do not occasionally appear during this period - Ariharadō, Iden....and Kichi to name a few during the 1820s. But these names generally appear alongside the seal of a major publisher." (4)

But why? The question is still unanswered. Considering the nature of the extended family in Japanese culture perhaps these minor publishers were related somehow to the larger houses. Perhaps some of the work was farmed out to them, but required the seal of the benefactor house for legitimacy. Still we don't know and wish someone out there could tell us. It would help in our overall understanding of the production of Osaka prints. If any of you know why or have a theory please contact us. We aren't averse to emending this page. |

|

1. The Theatrical World of Osaka Prints, by Roger Keyes and Keiko Mizushima, published by the Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1973, pp. 301 & 305. 2. Osaka Prints, by Dean J. Schwaab, published by Rizzoli, 1989, p. 11. 3. Ibid. 4. Ibid. |

紋

紋

HOME

HOME