JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Port Townsend, Washington |

|

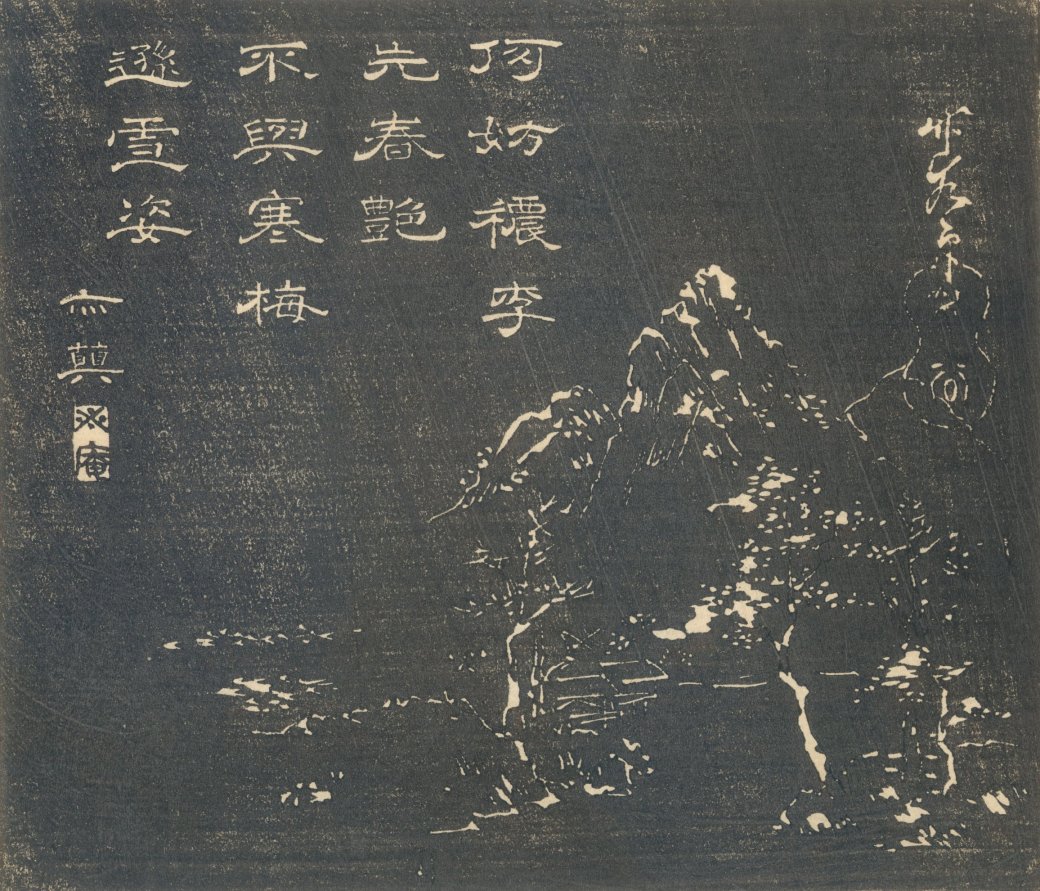

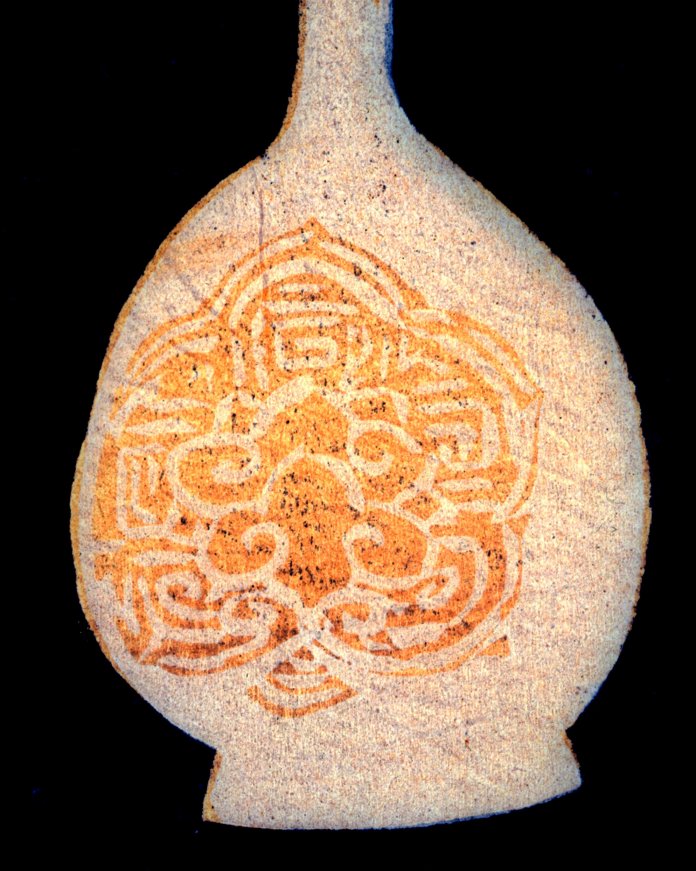

MIYAGI GENGYO |

|

宮城玄魚 |

|

みやぎげんぎょ |

|

(1817-80) |

|

Print type: harimaze |

|

張交図 |

|

はりまぜ |

|

Date: Ca. 1850 There is a very similar print by Gengyo in the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts in San Francisco - accession #1963.30.20308. It is dated from the 11th month of 1853 which puts it right in line with the approximate dating of our print which lacks censor and date seals. Although it has the mark of a different publisher that is not totally unknown for a single series of prints. To see a great reproduction of the Achenbach print go to famsf.org and do a search under Gengyo. |

|

Publisher: Maruya Tetsujirō |

|

Print Size: 14 5/8" 9 3/4" |

|

Condition: Good color with some soiling. Professionally hinged and matted. |

|

ORIGINALLY PRICED AT $135.00 NOW ON SALE FOR $90.00 REDUCED EVEN FURTHER TO $70.00 SOLD! |

|

CARVED IN STONE OR SO IT WOULD SEEM

ISHIZURI-E 石摺絵 |

|

|

|

The earliest pictographs in China carved on bones or tortoise shells were used by oracles. These images evolved into the complex Chinese system of characters each representing words or concepts totally unlike the lettered alphabet which we use in the West to form sounds. The explosion of specialized characters helped lead to the development of calligraphy and it is the art of calligraphy which concerns us here. Writing is considered the greatest art among the Chinese. So, for centuries wonderful examples were carved on stone monuments and steles because of their greater permanence. The precision and flow of each character was lovingly translated from the transience of the brush and ink into stone which were meant to last for the ages.

That is how and why the art of stone rubbings came about. Numerous museums today are filled with these rubbings although they are seldom shown to anyone other than the most interested scholars. For centuries rubbings spread calligraphic masterpieces far from their original settings.

The Japanese adopted and adapted many genres of Chinese art and scholarship. It was only a matter of time before someone would try to repeat the art of stone rubbing visually into woodblock print form. In the West there is a commonly known art phrase, trompe l'oeil which means 'trick the eye'. The translation of this concept into Japanese woodblocks is clearly expressed by ishizuri-e - literally 'stone-printed picture(s)'. "There can be little doubt that the method was adopted because of the Chinese associations, but the manner in which the imitation 'stone-print' was created could not have been more complicated or more demanding on the printer." (1) "This taku-hanga (rubbing or intaglio woodblock print) method of reproduction reverses the image and the background in the same manner as do traditional ink rubbings, so that the subjects appear uniformly in white and the background is inked with contrasting values of black or gray..." (2)

In the late 18th century Jakuchū (1716-1800) created masterpieces of this art. While he wasn't the first he raised this style to new and greater heights. Perhaps as early as the 1840s Hiroshige and his publishers began producing ishizuri-e. In the 1850s he came out with a whole series of harimaze much like the one by Gengyo featured on this page where one prominent area was done in the stone-printed style. Surely Gengyo knew these prints.

1. The Art of the Japanese Book, by Jack Hillier, published by Sotheby's, vol. 1, 1987, p. 311. 2. The Paintings of Jakuchū, by Money L. Hickman and Yasuhiro Satō, published by Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 1989, p. 24 |

|

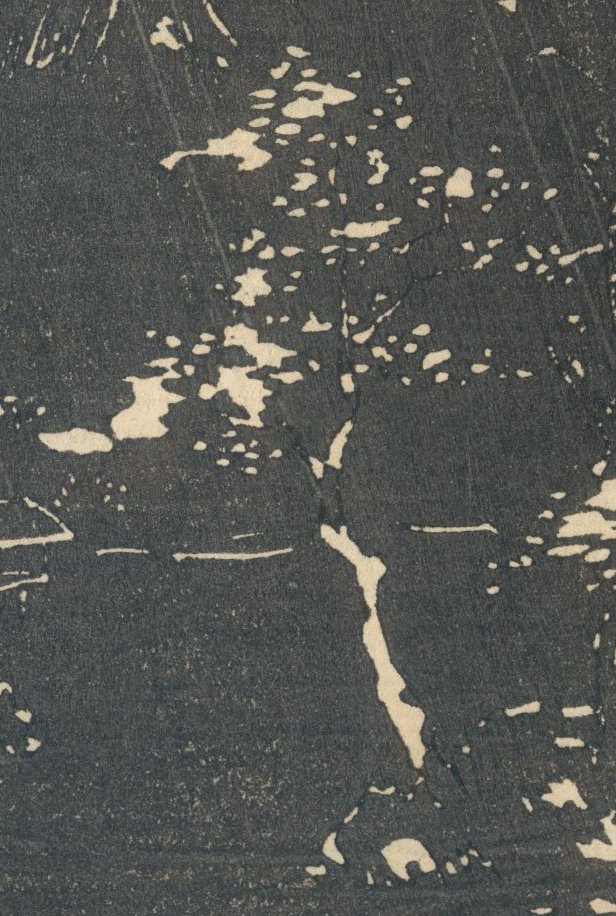

Above is an enlarged detail showing a tree with what I believe are two huts. |

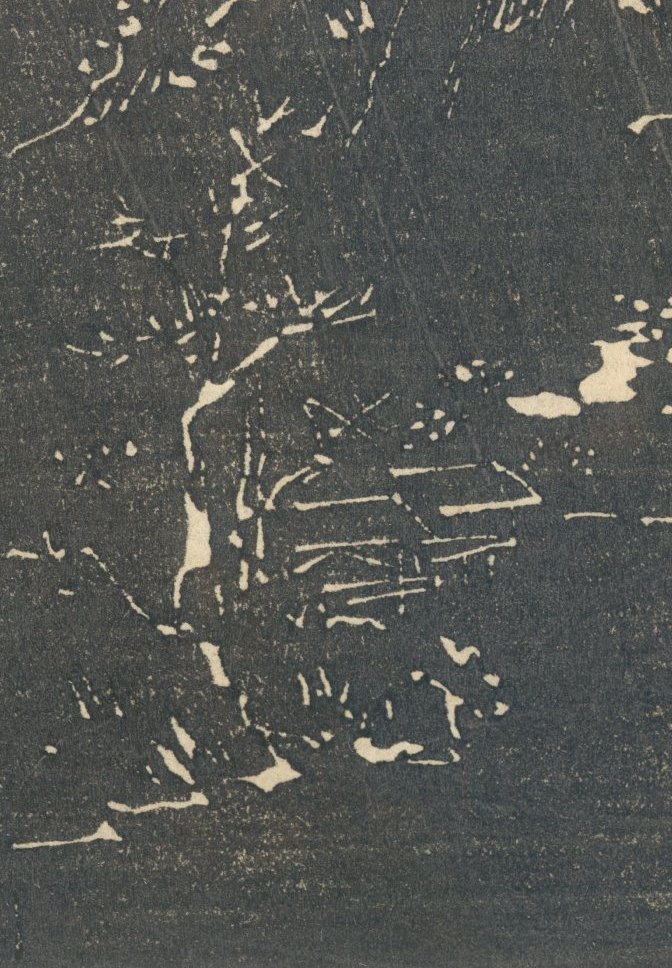

Another beautifully rendered tree. |

|

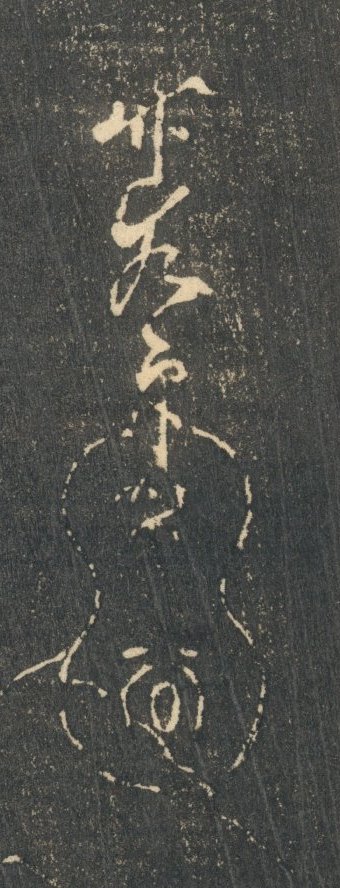

And a signature accompanied by a gourd-shaped seal similar to the one seen in red on the print near the deep blue vase. |

|

SUBTLETIES

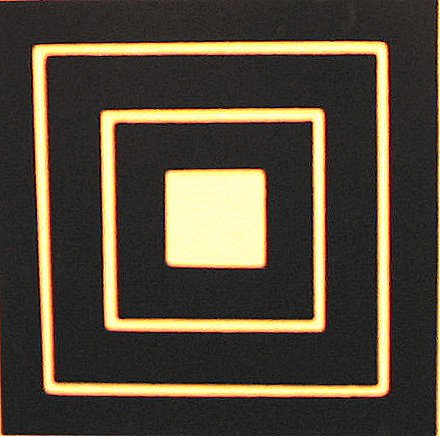

It is remarkable what is lost in the casual viewing of Japanese prints - even lesser ones. One would expect the most remarkable techniques to be used in the greatest prints by Utamaro or Kuniyoshi. A close study of such prints centimeter by centimeter - even millimeter by millimeter - reveals one sumptuous treat after another. Even lesser examples like the one illustrated on this page can be deceivingly simple at first glance, but look again. See the vase? It looks plain enough. Awkwardly drawn with slight moderations in color. Nevertheless, it practically hides its patterned surface. The enlarged detail below clearly shows that. Yet even in the magnified form it barely makes itself known. That is why I have added another example below tht showing it in the negative with contrast and brightness considerably enhanced. In that image the decoration is clear, distinct and obviously intentional. Go back and look at the prints in your own collections and if you are careful and patient I think you will be surprised at some of the 'new' things you will see in your old friends.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

HOME

HOME