JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

| Kansas City, Missouri |

|

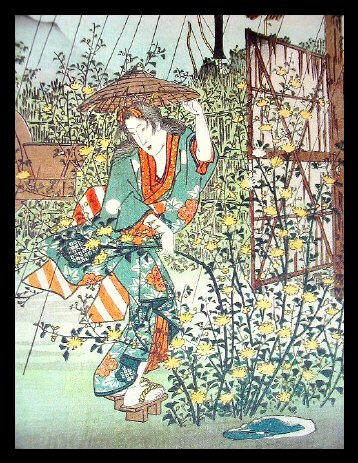

NISHIMURA HODŌ |

| 西村蒲堂 |

| にしむらほどう |

| Title: Yamabuki |

| 山吹 |

| やまぶき |

| Size: 15 9/16" x 11" |

| Date: 1939, 3rd Month |

| Showa 14 |

| 昭和14 |

|

From the collection of Robert O. Muller |

|

SOLD! THANKS D! |

|

Our great contributor A.K. has been invaluable in the construction of this page. Thank you A.K.! |

|

"He paused. 'And her yamabuki - it is in bloom as I cannot remember having seen it before. The sprays are gigantic. It is not a flower that insists on being admired for its elegance, and that may be why it seems so bright and cheerful. But why do you suppose it chose this year to come into such an explosion of bloom? - almost as if it wanted us to see how indifferent it is to our sorrows.' "

Quoted from The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu, translated by Edward Seidensticker, published by Alfred A. Knopf, 1992, p. 779. |

| HAPPENSTANCE |

|

Sometimes things happen which are totally inexplicable. After I added this print I searched the Internet for information about the Kerria japonica or yamabuki as it is called in Japan. I followed the standard procedures and hoped to find a site which not only would provide a good photographic image, but one which would permit my use of it without demanding that I jump through hoops or even more. After looking at a number of examples I ran across the image shown above, went to their home page, retrieved their e-mail address, wrote and hoped for the best. In no time at all I got a positive response. |

|

|

|

But there is a bonus for those of you who link to their page because not only is there basic information provided about the yamabuki, but the commentary is well written, personal and provides a remarkable amount of collateral information about this plant's place in Japanese history --- both literal and literary. So, do yourself a favor and either click on the photograph shown above or the link at the bottom of this section for a thoroughly enriching experience. |

| One more thing: for those of you who are interested in gardening, horticulture, whatever, explore the rest of Paghat the Ratgirl's site. I am sure it will be worth your time. |

| http://www.paghat.com/kerria.html |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The image shown above is a detail of print by Hiroshige from the 1840s. | |

|

Paghat's web page notes (with accompanying illustrations) the story of Ōta Dōkan 1432-1486 (太田道灌) stopping by the hovel of an impoverished family during a heavy rainstorm. He asked a young maiden for a raincoat. Instead she brought him a back a flowering branch of the yamabuki plant. (Note that like so many other Japanese tales there are several variations on this story.) Dōkan was infuriated at first, but came to realize later that the young woman was too poor to provide for his needs. But the significance of the story does not stop there because the use of the word yamabuki was layered with various allusions.

Paghat commented on the fame of this tale, but that is not what I knew best about Ōta Dōkan. For me his most important role in Japanese history was based on the fact that in 1487 he was the first war lord to build a castle at Edo, now called Tokyo. |

||

|

|

||

|

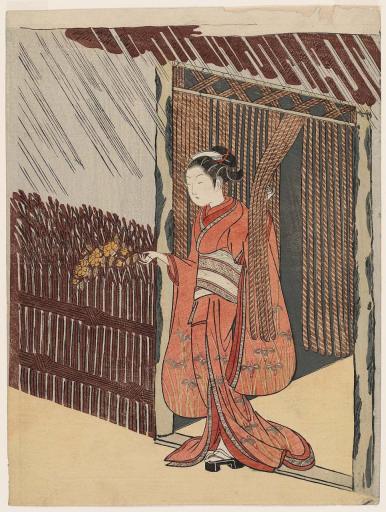

"Though untitled, the scene would have been recognized by its Edo-period viewers as a reference to an episode in the life of Ōta Dōkan... a warrior famous as the architect of Edo Castle. Once, visiting the countryside, he was caught in a rainfall and ran to a local residence to borrow a straw raincoat (mino). Instead of providing a raincoat, the young woman who answered the door wordlessly handed her visitor a branch of double-blossoming kerria. Dōkan flew into a rage until he was later reminded of the double meaning of a waka poem in the 1086 anthology Goshūi wakashū:

Nanae yae hana wa sakedomo yamabuki no mi no hitotsu dani naki zo kanashiki

Though it blossoms in myriad layers, the kerria rose, sadly, bears not a single fruit

In an alternate reading of the poem, the lines "not a single fruit" can be interpreted as "not a single raincoat." Realizing that, far from being rude, the woman's gesture had been an authentic and elegant expression of regret for being unable to grant his wish. Dōkan vowed to devote himself to the sudy of waka, later becoming a Buddhist priest.

This copy is from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

||

|

|

||

|

YAMABUKI AND THE TALE OF GENJI |

|

|

|

Paghat (click on the photo of the yamabuki on this page to go to her web site) mentioned that the Kerria japonica appears in the "Tale of Genji." A.K., one of our best contributors, sent me a list of several of the references.

He drew my attention to Edward Seidensticker's 1978 translation from chapter 41, "The Wizard". A.K. notes that it deals "...with Genji's crushing and inconsolable grief after the death of Murasaki." Since I have three separate translations I decided to make a comparison. They are listed below in chronological order beginning with Arthur Waley's translation from the 1930s, followed by Seidenticker's in the 70's and that of Royall Tyler in 2001.

Waley

"Spring advanced, and Murasaki's gardens took on their wonted splendour; but the sight of them gave him no pleasure, and indeed he longed to be in some place far off among the mountains, so bare and desolate that neither sight of flower nor song of bird would sharpen his sorrow. First the globe-flower reached its glory in a tangle of dewy blossom."

Seidensticker

"It was high spring and the garden was as it had always been. He tried not to remember, but everything his eye fell on brought such trains of memory that he longed to be off in the mountains, where no birds sing. Tears darkened the yellow cascade of the yamabuki."

Tyler

"The further the season advanced into spring, the more her garden looked just as it had then, but this gave him no pleasure, on the contrary, it was troubling, and so many things tugged painfully at his heart that he longed only for the mountains as remote as another world, where no bird would ever sing. The kerria roses blooming in merry profusion only called to his eyes a sudden rush of dew." |

|

|

|

SUBTEXT: A CAUTIONARY NOTE - BEWARE OF PEDANTRY

One of my favorite books in my library is Hokusai: One Hundred Poets by Peter Morse (1989) in which he states on page 9 "Every scholar has commented on the vast difficulty of translating Japanese poetry into Western languages. Despite this obstacle, there have been no fewer than fourteen complete translations of the One Hundred Poets anthology into English. (There have also been at least three into German, one into French, one into Italian and one into Ukranian.) Selecting among these has provided an embarrassment of riches." Later, and this is really important to keep in mind, he offers a "Comparison of Thirty-Six English Translations of Ono no Komachi (Poem Number 9)." Imagine 36 credible and decent variations on the translation of a single poem. All of you should keep this in mind when either reading, recalling or quoting a specific title, poem, commentary or passage. It would appear that there is no 'correct' answer. There are many. |

|

|

|

Yamabuki no utsurite ki naru izumi kana |

山吹の |

The yamabuki, dyes its waters yellow. |

|

HATTORI RANSETSU 服部嵐雪 1654-1707

|

||

|

|

||

|

Horohoro to yamabuki chiru ka taki no oto |

ほろほろと

山吹散か |

The yamabuki

petals - at the sound of the waterfall? |

|

MATSUO BASHŌ 松尾芭蕉 1644-1694

|

||

|

Composed at Nijikō (西河) on the Yoshino River ( 吉野川) where the rapids are said to be turbulent. This haiku was probably influenced by an the earlier poem of Ki no Tsurayuki shown below. |

||

|

|

||

|

Yoshino gawa kishi no yamabuki fuku kaze ni soko no kage sae utsuroinikeri |

吉野川 岸の山吹 吹く風に 底のかげさへ うつろにけり |

The yamabuki on the banks of the Yoshino River are scattered by the blowing winds changing their watery reflections |

|

KI no TSURAYUKI 紀貫之 882-945

|

||

HOME

HOME