JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

formerly Port Townsend, Washington now Kansas City, Missouri |

|

TOYOHARA KUNICHIKA 豊原国周 1835-1900 |

|

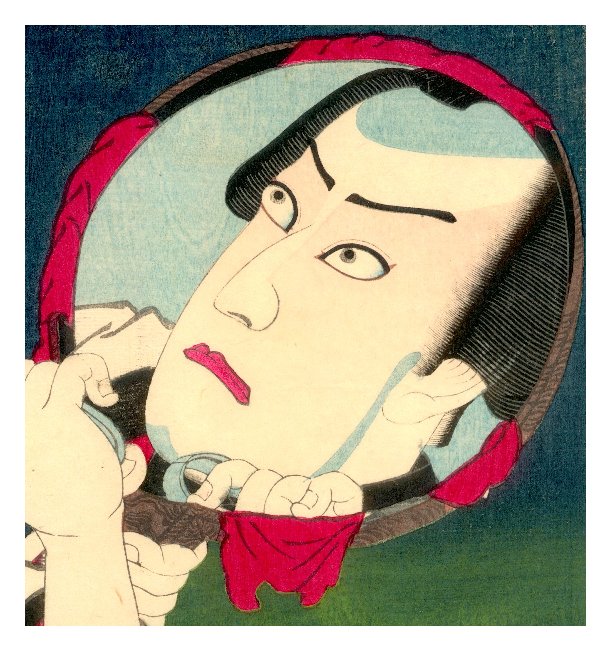

ACTOR: Kawarazaki Sanshō (1839-1903) 河原崎 三升 AKA Ichikawa Danjūrō IX |

|

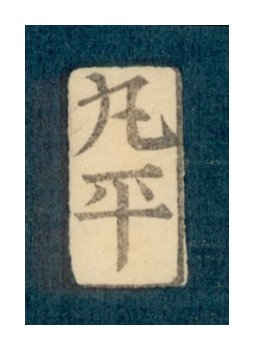

PUBLISHER: Maruya Heijirō

丸屋平次郎 |

|

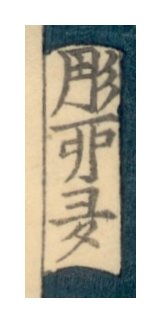

CARVER: Hori Uta

|

|

DATE: 1871, 11th month

Meiji 4 明治4 |

|

SIGNATURE: Toyohara Kunichika hitsu 豊原国周筆 |

|

SOLD! THANKS! |

|

Our contributor A. K. helped with the identification of this actor. Thanks A. K.! |

|

THE NAME SANSHŌ AND MY PROBLEMS RESEARCHING IT |

||

|

|

||

|

My first instinct was to grab for Leiter's compendium New Kabuki Encyclopedia. Unfortunately, for all of its qualities and the mass of information it provides, like all expansive studies, it has gaps which make the researcher's efforts all that much more difficult. In defense of Professor Leiter it must be said that it would be almost impossible for him to provide every bit of information regarding kabuki and its participants. That would probably involve the production of a multi-volume set of books and an entire staff of compilers. The New Kabuki Encyclopedia is a reworking of the Kabuki Jiten and in the preface Professor Leiter notes that it is "...in no way a mirror image of its Japanese counterpart." He adds that it was intended to correct errors of fact and printing of which there were many.

One problem: The name Sanshō does not appear in the entry on the Ichikawa Danjūrōs nor is it listed in the index. However, the information he does provide gives a good solid grounding for an understanding of this actor. Danjūrō IX was the fifth son of Danjūrō VII (1791-1859) by one of his concubines. "He was soon adopted by actor-manager Kawarazaki Gonnosuke VI and raised by him." That would explain the family name which he used early on in his career. His education was both intensive and extensive in all areas relating to the arts. In 1869 he took the name Gonnosuke VII, but "He left the Kawarazaki family and returned to the Ichikawa, assuming the name of Danjūrō IX that same year (1874).

As Danjūrō IX he stressed the psychological nature of the character and sought out new plays which were more historically accurate. This new approach did not sit well with the traditionalists, but the actor was convinced he was right. And for this modern kabuki owes him a great debt.

But...but...but what about the name Sanshō. Turns out that it had been used by other Ichikawa Danjūrōs as one of their poetry, i.e. literary, names. Extremely accomplished and literate figures they were often prominent members of poetry clubs and even added poems under that name to their contributions to surimonos. Yet it isn't as simple as that because like so many other aspects of the Japanese language and culture the name Sanshō operates on more than one level and can be understood in more than one way. (We have noted this layering of meanings on many other pages at this site. We can't even imagine what we have missed and is yet to be uncovered.) |

||

| IT IS A MATTER OF POETRY | ||

|

Sanshō as noted in the section above was a literary/poetic name adopted by a number of actors who had taken the name Danjūrō. Active members of poetry clubs they often added haiku and other forms to surimonos. Danjūrō VII under the name Nanadaime Sanshō added his thoughts to a print by Hokusai sometime in the first decade of the 19th century.* One print from ca. 1821 or 1822 by Kunisada in the Spencer Museum of Art in Lawrence, Kansas has a poem signed by "Sanshō VII". |

||

|

* There is a problem with the passage noted above. Leiter states that Danjūrō VII was born in 1791 while the Art of the Surimono published by the University of Indiana ascribes a poem and signature to him on a surimono designed by Hokusai as being no later than 1808. Actually they give the approximate dates as "1800-1808". If the earliest date was correct Danjūrō VII would have only been nine or ten years old. Not likely. The print cited was on loan from the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard for an exhibition in 1979. |

||

|

|

|

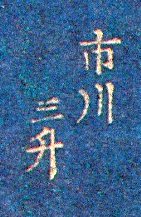

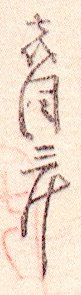

| Above is the detail of an Ichikawa Danjūrō VII signature (Ichikawa Sanshō) in metallic inks on a dark blue ground. It accompanies a poem he had written. | Above is the detail of an Ichikawa Danjūrō VII signature on a surimono designed by Kunisada from 1823. Note the freely written final character of Sanshō and contrast it with the more precisely printed form to the left. | |

|

|

||

|

THOSE DAMNED DIACRITICAL MARKS OR MACRON VS. CIRCUMFLEX OR ( ¯ V. ^ )

I have to admit that I am almost entirely intellectually deaf in my understanding of diacritical marks. Some of them make perfect sense to me, but others do not. When I took French there was a clear distinction between an accent aigue such as á and an accent grave as in à. With German it was umlauts (ä, ë, ö and ü ). Spanish had its tilde (ñ). I never studied the Scandanavian tongues so I never grasped å. My ear was not as bad as that of Steve Martin in "The Jerk" where he thought he was a little black boy, but he had no rhythm. I am not that bad. But these were all Western languages. Then I studied Mandarin and tonal differences. At the beginning of the course the distinctions were made perfectly clear. One could say mā - high and straight - and mean mother. Or, má - a rising tone - and mean hemp. Or, mǎ - falling, then rising - horse. Or, mà - falling - curse. However, because there is little standardization others will use numbers one through four to indicate those marks. And don't get me started on Arabic or any other foreign tongue.

All of this brings me to my problem with Japanese and the construction of this site. As I noted above there are gaps in the information provided by Leiter. But there are other issues too. He does list one actor as Ichikawa Sanshô, but almost everyone else refers to him as Sanshō. I cannot explain this. As best I can tell Leiter only uses the circumflex ^ and never the macron ¯. Perhaps it doesn't make any difference or perhaps it was sloppy typesetting and editing.

I have to admit that I have been terribly inconsistent here. My trangression with these diacritical marks is far worse than Leiter's --- that is if he has transgressed at all. I have no way of knowing. I only repeat the mistakes of others. Sometimes my source is writing in German or French and I tend to follow their lead with the assumption that they know better than I. But anyone who knows anything knows that we say Paris and the French pronounce it Paree or something like that. My point: Do they have a different approach to the use of diacritical marks? Is there no universality? No codification?

Also, my apologies to you all --- especially to sticklers. Sometimes I like using a font like Copperplate Gothic Bold and it just won't take accents --- or, at least on my computer it doesn't seem to want to. So, at the expense of accuracy and to satisfy my sense of aesthetics --- sometimes spelled esthetics --- I very cavalierly leave them out. (The Oxford English Dictionary gives 'haughty' as a synonym for 'cavalierly.')

Sometime in the recent past another Japanese print dealer/friend forwarded an e-mail he had received from a fellow in Florida. The message blasted my friend for quite a number of possible lapses he had made while listing a print for sale, but what I remember best was the attack on his use or lack thereof of diacritical marks. It was brutal and from our perspectives really rather silly. But I couldn't help thinking --- better he than me. |

||

|

|

||

|

On a personal note, as if all of this hasn't been personal enough, the use of diacritical marks don't mean diddly to most people. The average American lover of Japanese prints isn't even going to understand their use or the distinction they are making. It doesn't make a fig's difference if the name is written as Danjuro or Danjūrō. Either way they will get the meaning. The marks are there for the academics and the purists --- and a few others I dare not mention. |

||

|

|

||

|

THE COUNTERARGUMENT

In mid-December 2004 Professor Leiter in a correspondence with me was kind enough to clarify this issue. He wrote: |

||

|

"As for diacritics, both the caret or chevron over vowels and the macron are considered appropriate diacritics for Japanese. They are very important because their use not only indicates the long vowel for pronunciation, but because it also helps determine which word is intended when the diacritic is or is not used (Japanese being such a homonymic language)."

|

||

| This is not the first time I have been wrong, nor will it be the last, but it does go a long way in helping me personally to understand the use of such marks. | ||

|

On September 16, 2004 I received an e-mail from a visitor to this page which was first posted on the 11th. He told me that years ago he read Alan Watts The Way of Zen in which the author "...explained his non-use of diacritics in Sanskrit and Japanese words, saying that they would be meaningless to those who knew nothing of those languages, and needless for those who did." I am always grateful to know that there are others out there who might agree with me to some degree. |

||

|

TWEEZING

|

|||

|

|||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Above is a detail from a print by Harunobu which shows Daruma tweezing his beard by using water as a mirror. |

|

The detail above shows a courtesan tweezing her right eyebrow. This is from a series of beauties by Kunisada. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

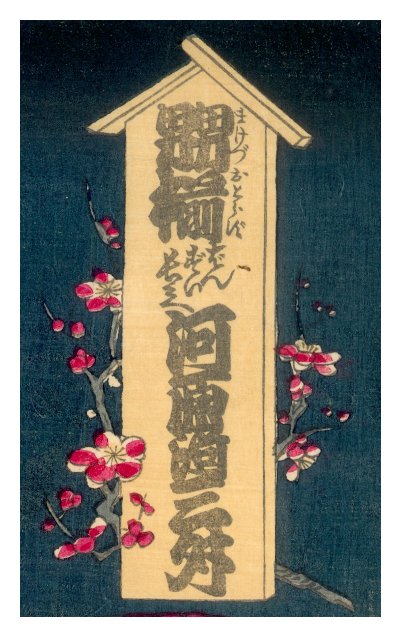

KANTEI STYLE 勘亭流 KANTEIRYŪ |

|

|

|

According to Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan (vol. 4, 1983 edition, p. 153) the Kantei style of calligraphy originated in 1779 (An-ei 8 or 安永8年) with Okazakiya Kanroku (岡崎屋勘六)an employee of the Nakamuraza (中村座). "Its thick, curved strokes form compact characters with few open areas between them, suggesting a 'full house,' and it quickly won favor in the theatrical world. Easily recognized at a distance...[it is still used today]." It is also used to announce the rankings of sumo wrestlers - although Leiter notes that their is a slight difference in style.

Leiter in his New Kabuki Encyclopedia (1997 edition, p. 281) provides additional information. "Minami Okazakiya Kanroku (1746-1805), a teacher of his family's calligraphy, who lived in Edo's Sakai-chô [堺町], created the style when he did the ônodai kamban...signing his work 'Kantei.'" Originally the Kantei style was used exclusively on kanban (看板) or billboards used to announce theatrical productions, but later were used for programs and scripts.

Kunichika or his publishers must have been very fond of this script because it appears so frequently on his theatrical prints. |

|

|

|

||||

|

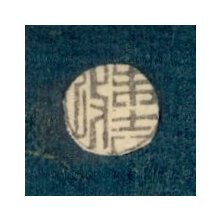

ARTIST'S SIGNATURE: TOYOHARA KUNICHIKA HITSU

WITH TOSHIDAMA SEAL |

|

TWEEZERS ARE FOR SPLINTERS |

||||

|

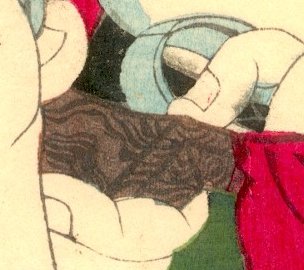

There is an interesting feature to this print. In fact, there are a number, but one in particular is the use of real wood grain for the reflective background in the mirror and a faux wood grain used for the handle and the frame of that mirror. |

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

|

|

||

| Real wood grain | Fake wood grain | |||

HOME

HOME