JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Port Townsend, Washington |

|

UTAGAWA KUNIYOSHI |

|

歌川国芳 |

|

うたがわくによし |

|

1797-1861 |

|

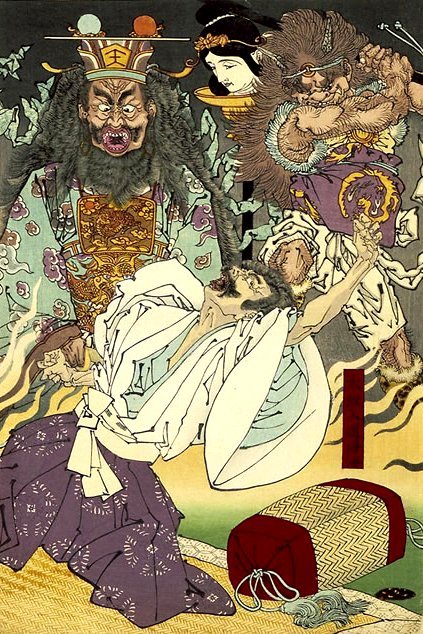

Subject: Death Portrait of Nakamura Utaemon IV in the role of Taira Kiyomori |

|

Date: 1852 |

|

Unsigned |

|

Publisher: Unknown |

|

版元: 不明 |

|

はんもと: ふめい |

|

Print Size: 14 1/4" x 9 3/4" |

|

SOLD! |

|

A note about the wallpaper on this page:

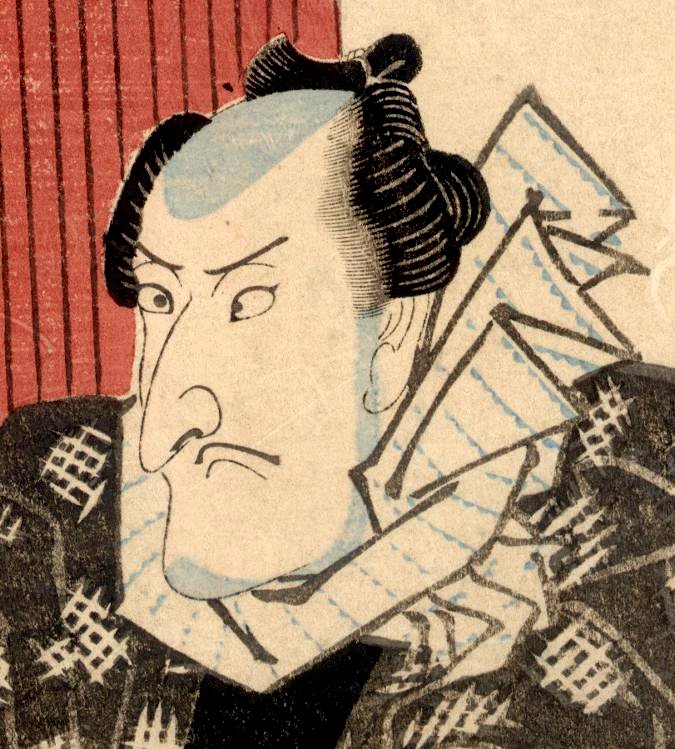

An anonymous source was kind enough to send me an image he owns from a series of Kuniyoshi graffiti prints which were published in 1847. Despite the childlike appearance of their scrawls the underlying hand of a genius is obvious. This series is one of my favorites of all time and from all places. After doing a little checking I was able to determine that this detail of a face in profile was none other than Nakamura Utaemon IV, the fellow being honored on the print featured on this page. The role in this sketch is unknown, but the hook of the nose and the intensity of the look make the identification undeniable. Besides, the catalogue from the Rijksprentkabinet cinched it. (Japanese Prints IV: Hiroshige and the Utagawa school, 1984, pp. 127-29) Had Kuniyoshi been a European artist we would be visiting museums today to see his more refined, elegantly rendered works, but there would also be shows dedicated solely to his remarkable caricatures. He would rank among the best. Like Kuniyoshi Picasso was also known for his ability to deftly capture the moment in a simple line even in his later years and to do so with an ease which betrays a far greater range of skills then would at first glance seem possible. Not every artist, only a very few in fact, have the ability to create such seemingly simple forms and to put them out there for all of the world to see and enjoy. Many have tried, but few have succeeded. Kuniyoshi should be positioned near the top of any such category. |

|

|

||

|

The tanka on this shini-e is by Umeya Kakuju (梅屋鶴寿 or うめや.かくじゅ) and makes a reference to Utaemon IV in his role of Taira Kiyomori (平清盛 or たいらのきよもり) 1118-1181. Amy Reigle Newland notes in her biographical entry on Kuniyoshi life and career in Heroes and Ghosts: Japanese Prints by Kuniyoshi 1797-1861 (p. 31) that the artist was a "...lifelong friend..." of the poet Umeya Kakuju. So, it would only make sense that he would write a dedicatory poem. |

|

|

|

The inscription at the top right reads:

[The actor's name] 中村歌右衛門

[His age at the time of his death and his poetic name] 行年五十五才

[His posthumous Buddhist name] 法名歌成院翫雀日光信士

[The last date he reportedly played the role, i.e., the 17th day of the 2nd month] . 二月十七日. |

|

The inscription at the top center to left reads:

火のきえしやうになしけりわさをきの平相国を名ごりにはして

Hi no keishi yō ni nashikeri wasa wo kino Taira Shōkoku nigori ni wa shite |

|

I once sold a triptych by Yoshitoshi which featured Kiyomori in his fevered hallucinatory death throes. Yoshitoshi was one of Kuniyoshi's pupil. Kiyomori obviously captured the passionate imaginations of more than one artist or actor. Below is the center panel of that triptych entitled "The Fever of Taira no Kiyomori" or Taira no Kiyomori hi no yamai no zu published in 1883. |

|

|

| THE EYES HAVE IT |

|

|

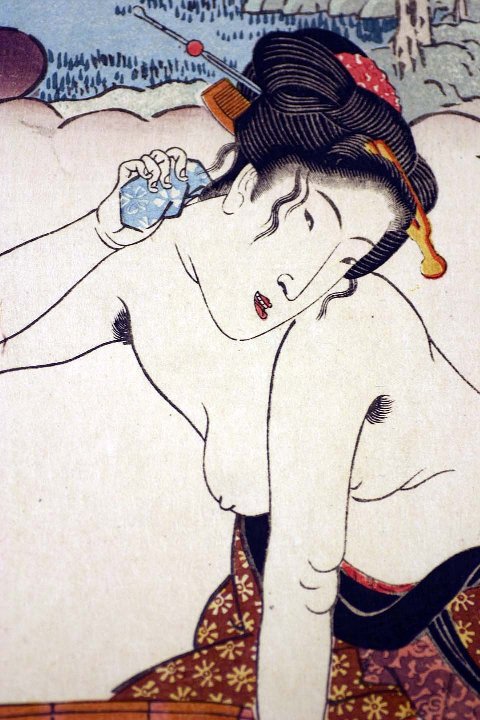

When I was a small child I learned the ditty about the purple cow.

I never saw a

purple cow;

What does this have to do with Japanese prints? Well, I'll tell you. The display of certain types of body hair on ukiyo prints is almost as rare as seeing or being a purple cow. However, in this shini-e or death/memorial print dedicated to the passing of Nakamura Utaemon IV the eyelashes are most definitely there. But this is not the only time an artist or his publisher/printers bothered to include such details. Recently an anonymous source sent me an image of a camel imported into Japan in the early 1820s. This exotic beast must have captured the imagination of all who saw it, but only Kuniyasu, as far as I know, gave us such a loving portrait which prominently display the animal's long, 'sexy' eyelashes. (See below) |

|

|

|

BUT IT WASN'T JUST EYELASHES THAT WERE RARE - THERE WAS ALWAYS ARMPIT HAIR TOO |

|

|

|

Above is a

detail from an image of an

*I corrected an error on October 20, 2014. I had originally identified this detail as coming from a Kunisada print when, in fact, it is from an Eisen. Sorry! |

|

|

|

BLUE IN THE FACE BLUE HAIR BLUE BEARD

Words take on different connotations in every language. Combinations of words work the same way. It is hard enough for one English speaker to understand the meaning of another English speaker. But let a person not raised in the nuances of a language speak to one who was and... Well, let's just say that wars have started for less. How many bar room conversations have ended tragically simply because someone else was inebriated and didn't understand the innocent remark? But then again one doesn't have to be drunk to fail to grasp a meaning. It happens within families all of the time. In "My Fair Lady" one of the lyrics reads "The moment he talks, he makes some other Englishman despise him." Isn't that the truth.

Literal meanings rarely cross the cultural and linguistic divides. That is why the French have an expression for such terms: faux amis ('false friends') or words that appear at first to mean the same thing in two different languages, but in reality don't. Actuellement may look like actually to an American, but in French it means 'at the moment'. A biscuit in America is not quite the same thing as in Britain. But enough of this: back to the subject of Japanese prints.

In Anthony Trollope's The Small House at Allington published in 1864 he gave us a new phrase: "And as to talking to her, you may talk to her till you’re both blue in the face, if you please.” [My italics.] This is an expression most native English speakers would now understand, but not others necessarily. They might get the gist, but still miss the mark. However, long before this passage was composed the Japanese were printing their portraits of kabuki actors with blue shading --- as seen on the portrait featured near the top of this page. This was a common practice to indicate the stubble of a man's beard. (See the detail of the head of Matsumoto Kōshirō V by Kunisada shown below. Note the line of light blue printed from near the middle of the ear and follow it down to the neck only to reappear as a triangular peak on the bottom of the chin. The blue pigment would indicate the thickest hair growth on a grown man's shaved face. As an aside: The speed or this printing or the lack of quality controls at the time of its publication allowed the sellers release this image even though the blue dye was printed over the lower part of the ear. I am fond of this print, but technically it is not perfect.) |

|

BLUE HAIR

Now here is an example of what I have been talking about. In the U.S. a blue hair is an older woman who has her hair done, even dyed, and the result is white with a bluish tint. 'Blue hair' is American slang and as far as I can tell is not an expression used in England or anywhere else. It certainly doesn't appear in the OED or in standard American dictionaries as far as I can tell. Maybe I should look harder. Anyway, that is not my point. My point is that the blue area on the top of the head of Japanese print representations of kabuki actors and monks is another attempt to represent the stubble left over from shaving off the hair. There are lots of wonderful stories about why actors shaved their heads, but I will save that for another time and place. Nevertheless, it is a telltale sign that the man portrayed is either one or the other, a monk or an actor --- with a few other exceptions. Why print it in blue? Why not gray or brown? I don't know. Perhaps it suited the Japanese esthetic sensibilities better. If anyone knows otherwise I would love to hear from you. I can always correct this page. |

HOME

HOME