JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Port Townsend, Washington |

|

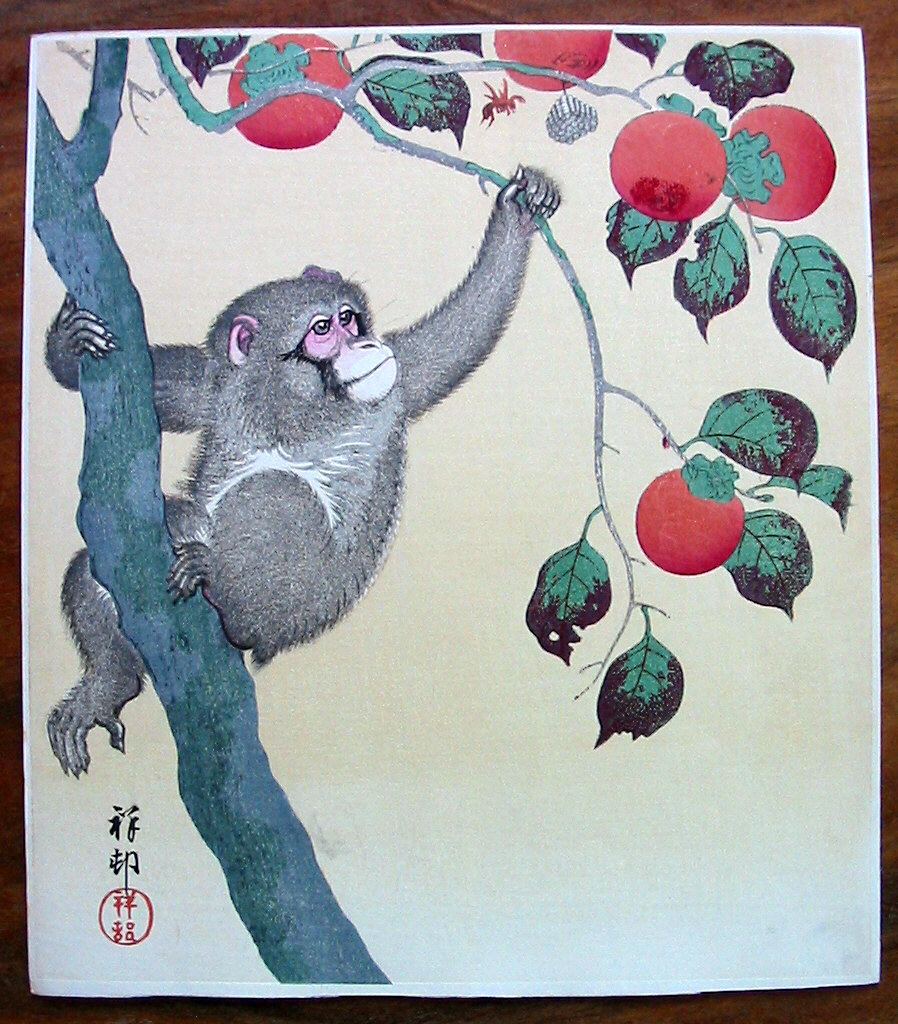

OHARA KOSON |

|

小原古邨 |

|

おはらこそん |

|

1877-1945 |

|

Monkey in a Persimmon Tree |

|

Date: 1935 |

|

Signature: Shōson |

| 署名: 祥邨 |

| しょめい: しょうそん |

| Size: 11" x 9 5/8" |

| Illustrated: Crows, Cranes & Camellias - The Natural World of Ohara Koson 1877-1945 Japanese Prints From the Jan Perrée Collection, by Amy Newland Reigle, Jan Perrée and Robert Schaap, by Hotei Publishing, Leiden, 2001, p. 201. |

|

$540.00 |

|

||

|

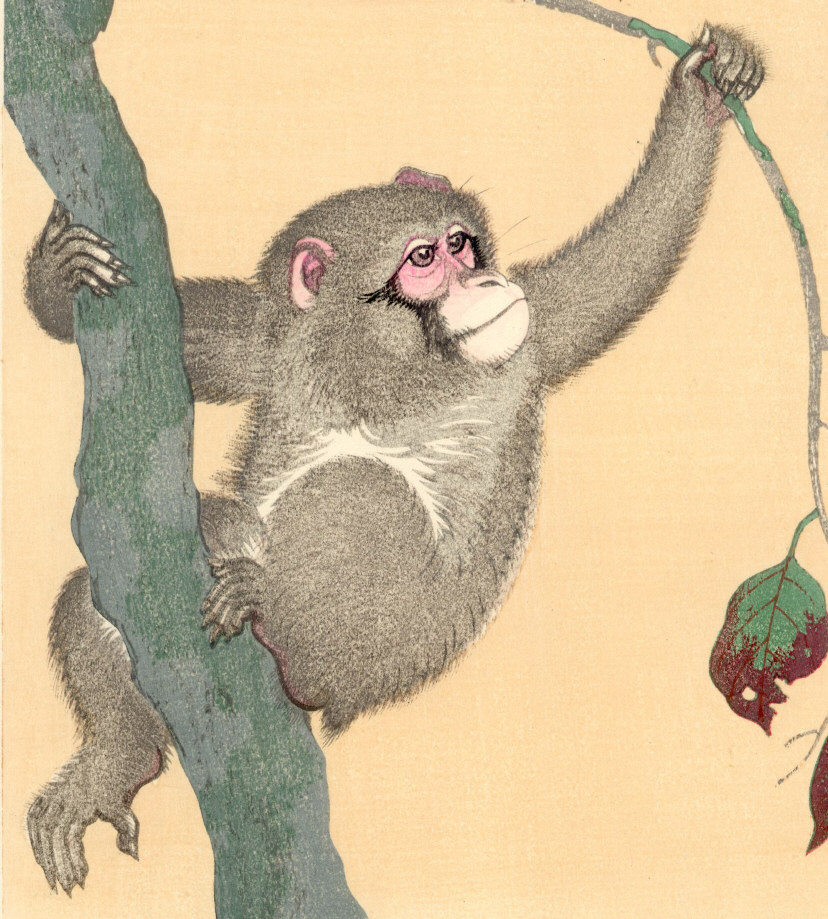

The Monkey and the Wasp

There is an exhibition right now of Edo Period paintings from the Price collection showing at the Sackler Gallery on the Mall in Washington, D.C. One of the works is a hanging scroll by Mori Sosen (1747-1821: 森狙仙 or もり・そせん) of a monkey 'tracking' a wasp. In a review in the Washington Post (November 15, 2007) Joe Price notes that this image is actually a visually pun. The words for wasp and fiefdom rhyme - hachi and hochi - as do the words for monkey and lord.* The moral: Watch out! If you are given a fiefdom by your lord you might get stung.

*My understanding of Japanese is not good enough to prove this concept right or wrong, but sometimes you just have to accept certain bits of information on faith. Besides, it sounds reasonable to me. |

|

Koson/Shōson/Hōson

Years ago I did some basic research on Koson. I was limited by my inability to read Japanese and by my overall ignorance. Being from Missouri I am also skeptical of almost everything through and through. Nevertheless, I did repeat the information which I was able to compile at that time: Koson changed his name to Shōson in 1912 and then quit producing bird and flower prints for the next 14 years. However, the latest thought on that hiatus has now been reconsidered by the experts. The gap may not have been so glaring after all. "...the artist may well have continued to use the name Koson into the Taisho period, thereby debunking the previous explanation that he ceased his printmaking activites from 1922 to 1926." (The New Wave: Twentieth-century Japanese Prints from the Robert O. Muller Collection, p. 123) The problem is that Koson didn't date his prints and unlike earlier periods there are no tell tale seals or stamps which can help us.

Then there is the issue of his background. "Despite a print legacy numbering in the hundreds, little is known about the life of Ohara Koson. He was born Ohara Matao in 1877 in Kanazawa..." Amy Reigle Newland notes that he reportedly was the student of Suzuki Kason who was grounded in traditional art movements. While Newland uses the word 'reportedly' to describe Koson's possible connection with Kason the Toledo Museum of Art catalogue from 1930 states definitively that he was his student. (Modern Japanese Prints, 1997 repro.) Helen Merritt repeats this in her Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints (University of Hawaii Press, 1992, p. 116): "Studied with Shijō-style painter Suzuki Kason." In The New Wave: Twentieth-century Japanese Prints from the Robert O. Muller Collection - Amy Reigle Stephens as general editor - the catalogue entry on Kason (p. 88) states that: "Ironically, however, the artist is best-remembered as the teacher of Ohara Koson (Shōson)..." The confusion may be more a matter of where Koson studied with Kason as opposed to whether he ever studied with him at all. Some sources say the student met the teacher in Kanazawa. Others say it was Tokyo. But Newland notes: "Matao's adoption of hte artist's name Koson - the son in Koson corresponding to the last character in Kason - would have been in keeping with the tradition of transmission from teacher to pupil and is perhaps additional proof of their association." (Crows, Cranes and Cemellias: The Natural World of Ohara Koson 1877-1945, Hotei Publishing, 2001, p. 9) If this leaves you a bit befuddled, forget it. Move on. When push comes to shove it is the final product of Koson's prints which count and that is really all that matters.

It is generally agreed that Ernest Fenellosa (1853-1908) encouraged Koson to send his paintings to the United States for exhibition and sale. His prints, too, were meant for foreign consumption. "Shōson was commissioned by Watanabe after 1926 to do both small souvenir prints....and full-size shin hanga. These decorative prints by Shōson, intended exclusively for export, are reported by Robert Muller to have been a staple of his own business in sending print exhibitions around to American schools in the early post-war period." (The New Wave, p. 33)

Now for the Hōson issue: This is the name he used "...on works published by Sakai-Kawaguchi." (Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints) |

|

THE PERSIMMON 柿 かき THE PRACTICAL FRUIT |

|

|

|

As far as I know the persimmon has no symbolic meaning in Japanese culture, but it certainly does have quite a few practical uses and associations. Grown on all of the islands except Hokkaido the persimmon is divided into two major categories - astringent and non-astringent. Both are edible under different circumstances, but it is the astringent kind that has some surprising applications. For example, in the production of gold leaf or kimpaku (金箔 or きんぱく) it is very important that the gold itself not become stuck to the sheets of paper used in the process. This is where the persimmon juice comes in handy. Gampishi (雁皮紙 or がんぴし), a special type of paper, treated with the astringent juice of this fruit, is made so smooth that the delicately thin gold will not stick to it even with additional pounding leaving it as thin as 1/10,000th of a millimeter thick.

|

|

|

|

WHAT'S IN A NAME?

One of my frequent correspondents has thoroughly enjoyed sending me articles about what possibilities the Japanese have for naming their children these days. Since 1990 the Ministry of Justice has increased the number of options considerably. A panel originally enlarged the selection with numerous other kanji characters and then the public was allowed to comment. At that point certain kanji were eliminated from the list like those which meant "hemorrhoid" and "debauchery". But others which are not likely to be used like "armpit" and "pots" were allowed to remain. Even "shrimp" or ebi stayed on the list, but is not likely to show up on kindergarten rosters. [This strikes us as even odder considering the history of the use of the kanji for shrimp. See our ebi page for numerous examples.] One kanji character which did make the cut was the one for persimmon which like its sister name strawberry may become far more popular. If Frank Zappa could name his children Dweezil and Moon Unit then as far as I am concerned the Japanese can name their children whatever they like --- even Persimmon. |

|

|

|

WHAT'S IN SAKE?

Some sake producers mix certain ingredients in shallow wooden troughs coated with persimmon tannin. |

|

|

|

IN FISHING

Prior to the use of nylon netting fisherman treated their nets with persimmon juice to keep them from rotting and to create surfaces which were smoother and less likely to bundle or snag. In this way the persimmon served a similar purpose to that used for making gold leaf as can be seen in the entry at the top of this section. |

|

|

|

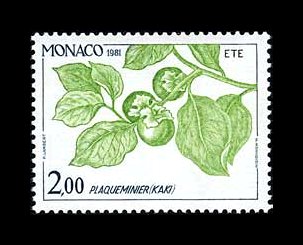

Above is a postage stamp issued by Monaco in 1981 showing a fruited branch of a persimmon tree. As you can see they used the French term for persimmon 'plaqueminier' and the Japanese 'kaki'. |

|

|

|

|

|

Stupid me! I set out to write something about persimmons in Japanese culture and totally forgot that one of my favorite personal objects is a very small and very, very heavy cast iron reproduction of that fruit. Its purpose? It is a vermillion seal ink holder. See the image below. (This item is not for sale.) |

|

|

|

|

|

Direct purchase may be made through check or money order or by payment through PayPal. |

HOME

HOME