JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

| Port Townsend, Washington |

|

Utagawa Toyokuni III |

|

三代歌川豊国 |

|

さんだい.うたがわ.とよくに |

|

1786-1865 |

|

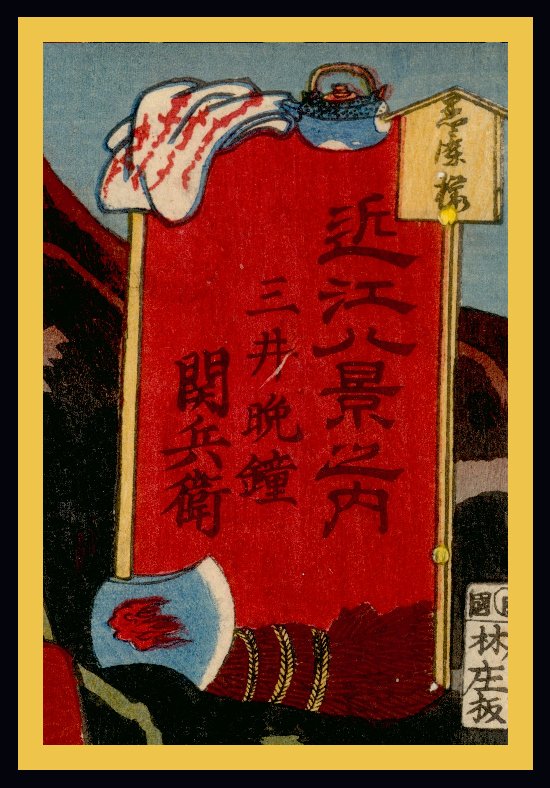

Title: Mii Bansho |

|

三井の晩鐘 |

|

みいばんしょう |

|

Series Title: Omi hakkei no uchi |

|

近江八景之図 |

|

Actor: Ichikawa Danzo VI |

|

市川団蔵 |

|

いちかわだんぞう |

|

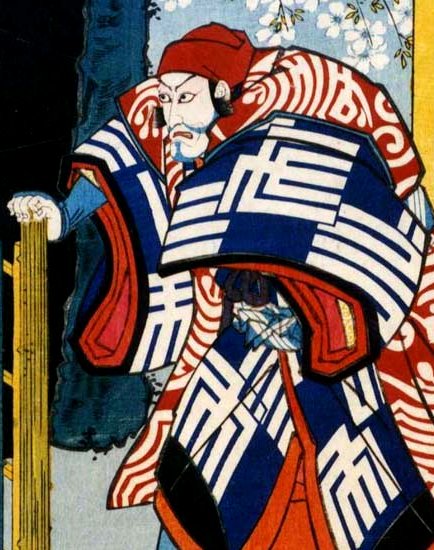

Role: Kuronushi |

|

黒主 |

|

くろぬし |

|

Publisher: Hayashi-ya Shojiro? |

|

Carver: Yokegawa Takejiro |

|

横川竹治郎 |

|

よこがわたけじろう |

|

Carver's Seal: hori Take (彫竹 or ほりたけ) |

|

Date: 1852, 6th Month |

|

Signature: Toyokuni ga |

|

Size: 14 1/4" x 9 5/8" |

|

Several areas are burnished like the black of his sleeve and Sekibei's hair. The darker areas of the landscape are flecked with mica. More subtle than any of these and impossible to reproduce in any photo or scan is the clear, but burnished interlinked toshidamas* in the title cartouche. (You would have to handle this print to see them for yourself.)

*The toshidama or otoshidama is the crest used by Kunisada/Toyokuni III and many other Utagawa artists. Kunisada used many variations of this as can be seen in the signature cartouche. |

|

SOLD! THANKS D! |

|

Otomo no Kuronushi 大伴黒主 |

|

|

|

|

|

The historical Otomo no Kuronushi was a ninth century poet whose family's stronghold was Otsu in Omi province which twice served briefly as the Imperial residence in the 7th century. With the advent of Buddhism and the emplacement of the Emperor in a more permanent setting in Nara and later Kyoto the power of the Otomo clan diminished. With the rest of the now-provincial clans, the Otomo, whose prestige and might preceded the Confucian and Buddhist restructuring of government, were seen as a potential source of unrest and sedition. More than that, as the brilliant urban Heian culture flowered at Kyoto, the provincial nobility came to be seen as illiterate bumpkins incapable of refinement but fit enough to supply the rice tax levy which enriched their betters at the Court.* |

|

|

*The information shown above was provided to us by A.K. Much of it is quoted without the marks because I have edited and rearranged some of the wording. My apologies to K. and hope he will appreciate my efforts. I certainly do his with enormous gratitude. Laura Resplica Rodd and Mary Catherine Henkenius in their Princeton Library of Asian Translations (1984, p. 416) note possible dates for Kuronushi as "830?-923?". They also point out that he was "One of the 'six poetic geniuses.' Member of a provincial family descended from the imperial line." |

|

|

|

|

| Kuronushi the Poet | |

|

ひいでて こひしきときは はつかりの なきてわたると ひとしるらめや |

Omoiidete koishiki toki wa hatsukari no nakite wataru to hito shirurame ya |

|

Lost in memories of our times of love: the first wild goose departs, lamenting and I wander lamenting too: Do you even remember? |

|

|

This is from the Kokinshu #735 and is translated by A.K., our contributor. |

|

|

近江のや 鏡の山を たてれば かねてぞ見ゆる 君が千年は |

Omi no ya kagami no yama o tatetareba kanete zo miyuru kimi ga chitose wa |

|

High it rises in Omi, Mirror Mountain, stands high established reflecting the thousand years our lord will reign |

|

|

Kokinshu #1086 transalted by A.K. |

|

|

|

|

||

|

Carver's Seal: hori Take representing Yokegawa Takejiro |

Date Seals: 1852, 6th Month |

Publisher's Seal: Hayashi-ya Shojiro?

Trimmed on the right. |

||

| A BUM WRAP? |

| "Both Kuronushi and the formidable woman poet Ono no Komachi were preparing their entries for a poetry competition to be held in the Emperor's presence. Kuronushi, anxious that Komachi's poem might be better than his, lurked near her house and overheard her practicing her recitation. Struck by the excellence of her verse and unwilling to lose to her, he formed a devious plan. Memorizing her poem, he wrote it into a copy of the ancient anthology Man'yōshū. After her recitation at the contest, Kuronushi accused her of plagiarism and produced the Man'yōshū to prove it. Komachi, quick-witted though astonished and stung by Kuronushi's treachery, asked for a basin of water to be brought. She dipped the manuscript into it, and as she did so, the fresh writing of Kuronushi's forgery washed away, while the ancient writing remained. Kuronushi's deceit exposed, she won the prize."* |

|

* We are grateful to A.K. for contributing this tale. He went on to say that whether this is simply based on malicious court gossip or not it is enshrined in the Noh play Soshiarai Komachi (草紙洗小町) and has blackened Kuronushi's reputation ever since. Logic tells us that someone out there or perhaps a whole faction was intent on dissing the man. Anyone and everyone competently literate at the time when this story would have taken place would have known that that was not an old poem.** **Donald Keene in his Seeds in the Heart: Japanese Literature from Earliest Times to the Late Sixteenth Century (p. 245) notes that the compilers of the Kokinshū wrote "...one of the earliest and best known documents of Japanese poetic criticism." They stated that none of the Six Immortal Poets of the ninth century could rival the poets of the Man'yōshū. Ono no Komachi's poetry was said to be weak "...like an ailing woman wearing cosmetics." But if that weren't bad enough Kuronishi took his own pounding: "His style is extremely crude, as though a peasant were resting in front of a flowering tree." And that wasn't even their harshest appraisal. |

| SEEING STARS | ||

|

||

| In the kabuki play Seki no To (関の扉 or せきのと) the villain Otomo no Kuronushi (大伴黒主 or おおともくろぬし) is portrayed as the character Sekibei. He is plotting to take over the country. In this scene he is disguised as the guard of a barrier gate. While drinking from a red lacquer bowl "...a stylized black and silver cloud appears, and within it the stars of the Big Dipper. He sees them reflected in the [bowl], notes the position of Saturn, and realizes that this is the precise moment to cut down the...[large black trunked, blossoming] cherry tree [nearby]." Burning the wood of the tree will help him in his efforts to usurp power. However, the tree is possessed and before he can cut it down a female spirit appears. They struggle --- one of the most dramatic scenes in kabuki --- and in the end Sekibei is thwarted. | ||

| A visitor to this site and frequent correspondent of mine has pointed me in the right direction many times. After I posted this image on the Internet he asked in an e-mail what the yellow "sparklies" were in the bowl. At that point I didn't know and told him so. He did the basic research and provided me --- and you --- with the answer. For purposes of modesty or discretion he prefers being referred to as "AK." Thank you AK. Now we all know. | ||

| THE NATURE OF SEKIBEI'S COSTUME |

|

| While Leitner makes a point of describing Sekibei's costume it does not jive with those of the print featured on this page or that of the detail of the image shown immediately above which is also by Toyokuni III but portraying Ichikawa EbizŰ V here. Perhaps it is poetic license or perhaps I have not seen the exact costume to which Leitner is referring. He states that Ono no Komachi "...requests passage through the barrier, but is refused by the barrier guard Sekibei, dressed in a bold, green and white, checkerboard-patterned (ichimatsu moyō) padded kimono, with a brown turban-like cap on his head."* Clearly Leitner must be noting the oddly designed costumes seen on this page which seem to be unique to this particular character. |

|

* The New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of the Kabuki Jiten, by Samuel Leiter, Greenwood Press, 1997, p. 565. |

|

THE FINEST KABUKI SITE ON THE INTERNET! |

| http://www.kabuki21.com/index.htm |

|

For additional information about and images by various artists of Ichikawa Danzo VI link to the web site below. |

HOME

HOME