JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

formerly of Port Townsend, Washington now Kansas City, Missouri |

|

TSUKIOKA YOSHITOSHI |

|

月岡芳年 |

|

1839-1892 |

|

Foreign Means of Conveyance Gaikoku kuruma zukushi no zu |

|

外国 車 盡 (?) 之 圖 |

|

10th Month, 1871 Meiji 4 明治4 |

|

Print Size: 13 3/4" x 9 1/8" |

|

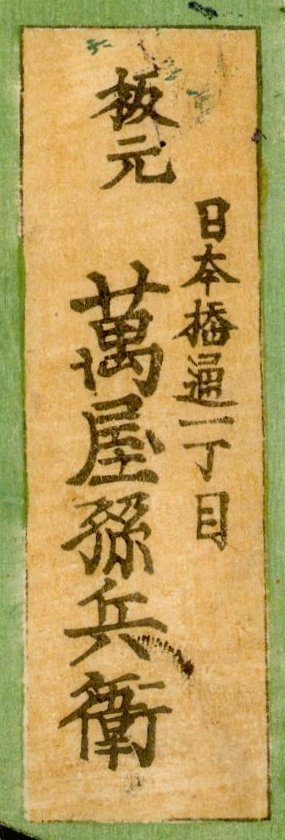

Publisher: Yorozu-ya Magobei 萬屋孫兵衛 よろずや.まごべい |

|

Signed: Oju Yoshitoshi (something) |

|

There is another copy of this print in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. |

|

$320.00 SOLD! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DOES ANYONE KNOW WHY.....? AND CAN YOU CORROBORATE IT? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

If anyone knows what is used as a covering for the wheels of the cannon would you please write to me and let me know. Is it fur or straw or what? Also, do you know why? Do you know of any other illustrations or early photograph of this practice? Please! please! please! let us hear from you.

PROPOSITIONS:

So far two [now three] people have told me why they think the wheels are covered. Personally I wish someone would give me some solid documentation, but until they do these two suggestions sound absolutely reasonable to me.

The first was made by a fellow I met who lives on a boat and is a musician. He said he was sure the wheels were covered to muffle the sound of the approach of the cannon. That way one could surprise one's enemies with a sneak attack.

The second suggestion comes from Barbara Mason, an artist, who contacted me by e-mail and makes an equally thoughtful argument. She said: "It seems pretty obvious that the covering for the wheels in the Yoshitoshi print was to keep the wheels from sliding in mud...the covering would give a lot more traction. It looks like cloth with something inside, maybe straw. I am no historian...so this is a guess."

What do you think?

I'm waiting. |

|

|

AT LAST - A FULLER RESPONSE (This might just be the one we have been waiting for.)

In September 2010 we received the following e-mail from Stephanie G. -

From various books,

including books about the US Civil war and the Wellington campaigns, the

covering for the wagon wheels was whatever was available (straw, brush,

rags, small branches) when the need arose for the following purposes:

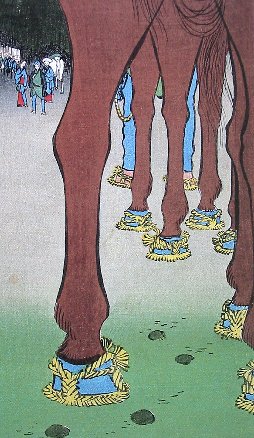

Above is a detail form a Hiroshige print showing the hooves of the horses and the feet of a man protected by straw

coverings. In a follow up message Stephanie G. added:

Here's one quote about the

wheels - Napoleon is sneaking his artillery wagons past an Italian fort

(Fort Bard). "Tow" is the waste fibers from flax or hemp, used at that time

for swabbing out cannons, filling mattresses - a general purpose fiber. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

Publisher: Yorozuya Magobei |

|

|

Signature: Oju Yoshitoshi (something) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Date Seal: 1871, 10th Month |

|

|

|

THE RICKSHAW WAS NOT A FOREIGN VEHICLE |

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

OR WAS IT? |

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

人力車 JINRIKISHA じんりきしゃ (literally: a man-powered vehicle) |

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

There is much confusion over the origin of the rickshaw. Was it invented by the Japanese or by Westerners? Or both? The sources vary considerably. The Dictionary of Japanese Culture states: "There are two theories as to its invention: one, that it was an invention of Yōsuke Izumi, and the other that it was invented by Jonathan Goble (died 1898), an American Baptist missionary. They first appeared in Tokyo in 1870 as a public conveyance replacing the kago (palanquin)." (1) The Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan tells a somewhat different story. "Said to be invented by three Japanese, who claimed to have been inspired by the horse-drawn carriage which had been newly introduced from abroad, the rickshaw was produced on a large scale after the government permission was obtained in 1870." (2) However, on the second point it did agree: "Because of its speed and mobility, it quickly replaced the palanquin (kago)." (3) Julia Meech-Pekarik sides with the Japanese inventor Yōsuke Izumi and notes that with the help of two friends and a government license had a three year monopoly and that by 1872 there may have been 50,000 rickshaws on the streets of Tokyo. She even emphasizes it significance by calling it "...perhaps the most momentous transport innovation of the Meiji period." (4) |

||||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

|

The detail on the left of an engraving by Huquier after a painting by Claude Gillot ca. 1700 clearly shows a rickshaw like carriage drawn by a donkey. In another painting by Gillot, "Les deux carrosses" in the Musée du Louvre, two figures from the Commedia dell'Arte pull two similar vehicles replacing the animal with man power.(5) |

||||

|

1. The Dictionary of Japanese Culture, by Setsuko Kojima and Gene A. Crane, Heian International, Inc., 1991, p. 126. 2. Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, entry by Tsuchida Mitsufumi, 1983, vol. 6, p. 311. 3. Ibid. 4. The World of the Meiji Print, by Julia Meech-Pekarik, Weatherhill, 1986, p. 84. 5. Anyone familiar with these web pages must realize by now that I am intrigued by more than just one narrowly focused subject. While researching Gillot's representations of these two wheeled vehicles I ran across a surprising term for them: vinaigrette. I knew that a vinaigrette was a mixture of oil and vinegar which I put on my salads, but I did not know that it was also a type of carriage. The first known reference to that term was made in 1660. Harrap's New and Standard French and English Dictionary, vol. II, p. V:18 refers to it as a "two-wheeled sedan" with the notation that it is categorized as an ancient usage. It also notes that faire vinaigre means "to hurry." Perhaps there is a tenuous connection there, but for the life of me I can't figure it out. ***Here is an update: Yesterday, June 15, 2004, I ran across another French dictionary in my library which I had overlooked earlier. According to the Dictionnaire du Français non Conventionnel by Jacques Cellard and Alain Rey and published by Hachette in 1981: "Début du 19e siècle. De 'vinaigre!', injonction par laquelle les enfants invitent un(e) camrade à presser le mouvement de la corde à sauter, dans le jeu. Sans doute convergence de faire vite! et de l'idée d'acidité, de piquant, du vinaigre." (p. 830-1) |

||||||

|

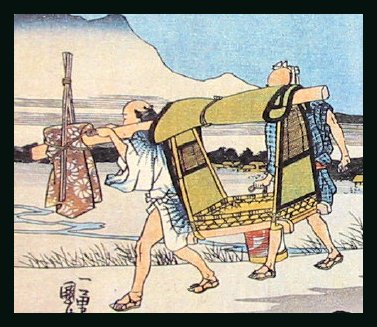

|

According to Meech-Pekarik the kago (篭 or かご), like the one to the left shown here, was the most popular form of comfort transport prior to the introduction of the rickshaw. This detail of a Kuniyoshi print shows a simple kago. More elaborate earlier ones were called koshi (輿 or こし). The difference would be somewhat comparable in modern terms between riding in a Lexus or a Yugo. |

|

||||

|

|

||||||

|

|

There was a much earlier form of luxury travel reserved for the highest members of the Imperial court: the gissha (牛車 or ぎっしゃ) or ox carriage. These traveled along at the lightning speed of about 2 mph under the best of conditions. The detail of print by Hokusai to the right shows one of these carriages and, although it is not readily visible, a reclining ox in the lower right with its draped back to the viewer. |

|

||||

|

"AN EIGHTH WONDER OF THE WORLD" In A Dictionary of Japanese Artists Laurance P. Roberts points out that Yoshitoshi changed his family name to Taiso (大蘇) after 1873. In the foreward to Beauty and Violence: Japanese Prints by Yoshitoshi 1839-1892 the first reference is to Tsukioka Yoshitoshi while on the next page is the memorial print by Kanaki Toshikage called "Portrait of Taiso Yoshitoshi." Koop and Inada in their Japanese Names and How to Read Them (p. 69) refer to art-names as gō. "Although often quoted in company with the ordinary names in signatures, the gō is regarded as independent of them - belonging to another and higher life, as it were." As if all of this weren't daunting enough Andrew Nathaniel Nelson states in his The Modern Reader's Japanese-English Character Dictionary: Second Revised Edition (p. 10) "The readings of characters in personal and place names constitute quite a separate problem from ordinary words, one that could never be adequately treated within the scope of a portable dictionary, if indeed a fully satisfactory solution can ever be found. Probably, the most thoro study made to date is the Japanese work by Araki Ryozo, Nanori Jiten... As Mr. Araki humorously puts it, this problem of Japanese names is indeed an eighth wonder of the world."

|

|

|

|

THE NAME GAME

Sexton gives a range of dates for when Kunisada

dropped his former signature and took up his new one. According to Sexton

Kunisada quit using the Kunisada Kōchōrō "...signature on the 7th day

of the new year 1844."

|

HOME

HOME