|

JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

formerly Port Townsend, Washington now Kansas City, Missouri |

|

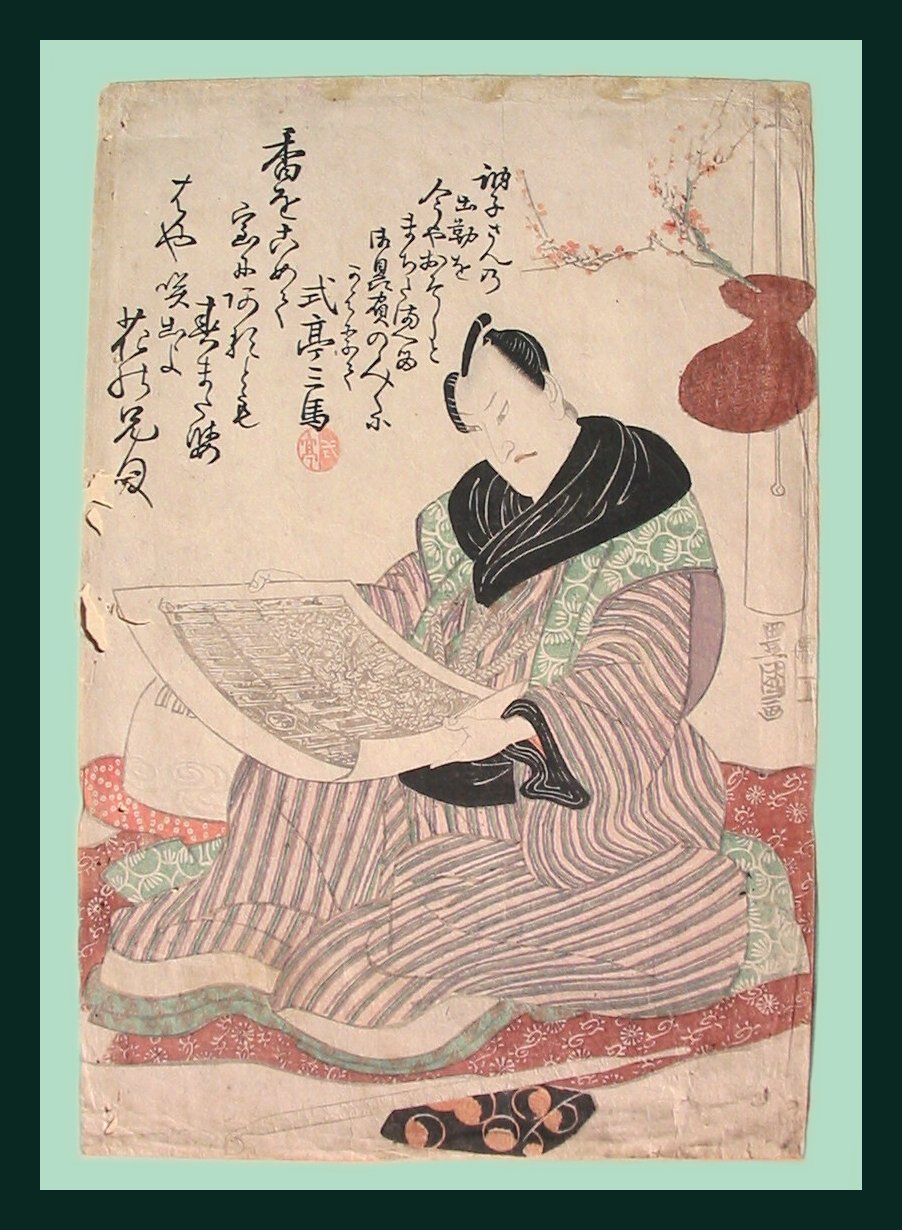

UTAGAWA TOYOKUNI I |

|

歌川豊国 |

|

1769-1825 |

|

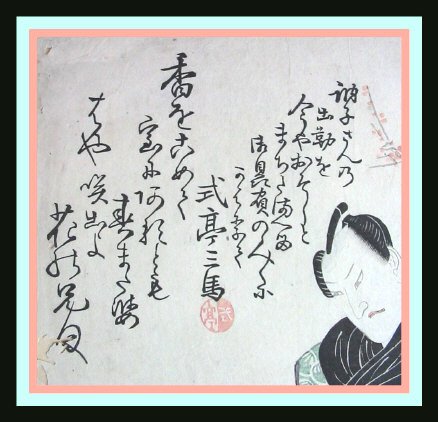

Portrait of Sawamura Sojūro IV (1784-1812) 沢村宗十郎 viewing a Nakamura-za theater program |

|

Signed: Toyokuni ga |

|

1811 Bunka 8 文化8 |

|

15" x 10" 38.1 x 25.4 cm |

|

The Poem is by Shikitei Samba 式亭 三馬 1776-1822 |

| Publisher: unknown |

| 版元名: 未詳 |

|

Condition: Fair, soiling, worm holes, stains and wrinkling on edges, but still a great print! |

|

There are other copies of this

print in the Tokyo-Edo Museum and at Waseda University. |

|

Originally priced at $360.00 Now on sale for $240.00 NO LONGER AVAILABLE! |

|

|

In a Sotheby's catalogue from 1993 they speculated that this print was created possibly to commemorate the change of name of this actor from Sawamura Gennosuke to Sawamura Sōjūrō IV - which had taken place the year before he died in 1811. |

|

|

Below is the printed text of

the inscription by Shikitei Samba |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

訥子さんの

式亭三馬

香をこめて

"On behalf of the fans who are anxiously awaiting Tosshi's comeback and success as the elder brother of another popular actor Tanosuke"

Tosshi was Sawamura Sojūro IV's haimyō or poetry name. |

|

|

|

THE FINEST KABUKI SITE ON THE INTERNET! |

|

http://www.kabuki21.com/index.htm

Many of the people who are reading this will already know of this site. But if you don't then go to it and definitely bookmark it as one of your 'favorites.' It will serve you well. There is material to be found there which is hard if not impossible to find anywhere else. This is a great site for students, collectors, dilettantes and the just plain curious. |

|

|

|

For More Information on and Images of Sawamura Sōjūrō IV click on this specific link below

|

|

|

|

All of that said, this kabuki site provides more supplement information, both visual and written, than any other I know when it comes to viewing the actor prints which I am offering. With their kind permission I will be adding links to individual pages for you to expand your own knowledge base. Make use of it. Below is a link to a single page dealing with Sawamura Sōjūrō IV. Follow their internal links to see more examples --- and make sure you note the use of the kangiku or 'chrysanthemum viewing' mon which appears repeatedly on Sōjūrō's robes and which are discussed on this page.

|

|

THE DRINKING OF CHRYSANTHEMUM DEW |

|

There is a wonderful two volume catalogue on Utamaro which is more than a mere listing of this artist's productions. It also serves as a partial guide into the world of late eighteenth and early nineteenth century Japan. The description for a hanging scroll (cat. #4, "Courtesan in procession") also provides a translation of the inscription at the top. This makes a reference to "...chrysanthemum dew from the Sweet Valley [Amaya no Kikusui]..." Like so many other literary passages this one is an allusion to a Chinese source. Here it is to a fabled Chinese river which flowed with the essence of chrysanthemum dew. Those who drank from it were said to never age.* |

| *The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, by Shugo Asano and Timothy Clark, British Museum Press, 1995, text volume, pp. 77-78. |

|

|

|

THE CHRYSANTHEMUM AND THE TALE OF GENJI |

|

|

|

In the second chapter of The Tale of Genji two remarkable references are made to the beloved/revered chrysanthemum. The first in Royall Tyler's wonderful translation appears on page 30 of volume one: "The chrysanthemums had turned very nicely, and the autumn leaves flitting by on the wind were really very pretty." Tyler explained that "Frost withered chrysanthemums were prized." How odd? There must be something more to this. Something metaphorical about a faded beauty. But I am only speculating.

Even more interesting for the non-scholar and English reader is the fact that one's interpretation of the Tale of Genji depends greatly on which translation is being read. For example, Arthur Waley's version (p. 35) is considerably different here: "The chrysanthemums were just in full bloom..." There is no mention of frost or the flowers being past their prime. On the contrary, here they are "...in full bloom..." Seidensticker (p. 36) on the other hand does mention frost: "The chrysanthemums were at their best, very slightly touched by the frost...".

The Zen monk Godō (梧堂) who died in 1801 left a death poem which may allude to a frost bitten blossom: "Chrysanthemums were yellow/ or were white/ until the frost." (Japanese Death Poems: Written by Zen Monks and Haiku Poets on the Verge of Death, introduction and commentary by Yoel Hoffmann, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1996, p. 173.)

The second reference in Genji is surprising, but maybe not as much as the first one because it deals once again with chrysanthemum dew (p. 35). Genji and his friends are lying around discussing the different types and aspects of women. One of them mentions the Chrysanthemum Festival, trying to write the appropriate Chinese poem, "...and here comes a lament from her, full of 'chrysanthemum dew'..." Fortunately Tyler footnotes this passage because otherwise it would have passed me by completely. In note 47 he writes: "Ladies moistened a bit of chrysanthemum-patterned brocade with dew from chrysanthemum flowers, rubbed their cheeks with it to smooth the wrinkles of age (since chrysanthemum dew conferred immortal youth), and composed poems lamenting the sorrows of growing old." |

|

|

|

The chrysanthemum flower displayed above is shown courtesy of Shu Shuehiro and his wonderful botanical site. We would encourage you to visit it at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. There is much more to be seen there. Something for everyone interested in nature and its marvels. |

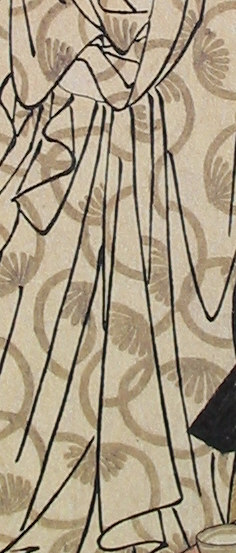

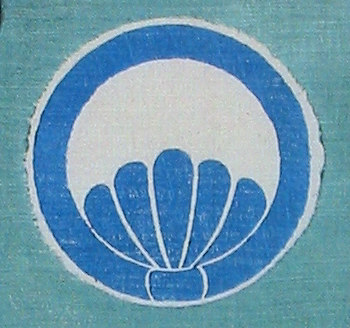

| kangiku |

| 観菊 |

| CHRYSANTHEMUM VIEWING |

| our background motif |

| The kangiku motif is a stylized chrysanthemum used as a mon or crest by Sawamura Sōjūrō IV. Translated literally kangiku means 'chrysanthemum viewing'. |

|

We chose this chrysanthemum motif for its beauty, simplicity and elegance. Our choice was aesthetic and totally unintentional regarding its historical significance. However, while researching this print we encountered several other examples of either almost exactly the same robe or other robes with variations on this mon. These examples are listed below: 1. A print by Toyokuni I of Sawamura Gennosuke I (later Sōjūrō IV) from ca. 1801. The figures in this print are much more crudely drawn and the kangiku motif on the robe is much more pronounced. 2. The central panel of a triptych by Kuniyoshi from 1834 showing Sawamura Sōjūrō V as Matsue Kurando. Here the kangiku motif is small and isolated like golden rings in a field of deep green. 3. A print by Kiyonaga from 1788 Sawamura Sōjūrō III as the courtesan Takao. This onnagata's kangiku motif appears on the obi. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

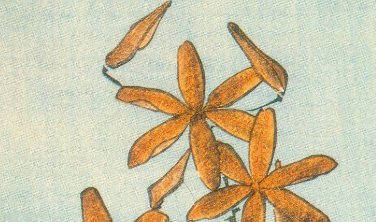

Above is a chrysanthemum mon detail from a print from 1843-47. This is a beautiful interpretation which is meant to reproduce a paste-resist fabric decoration or tsutsugaki (筒描き) in woodblock print form. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Detail from a Kunisada print from ca. 1830-35. |

Detail from a Toyokuni I print from ca. 1815. |

|

|

Detail from a Toyokuni I print from 1811. Click on the image above to go to that print. |

|

||

| Detail from a Shunsho print ca. 1780. |

|

CHRYSANTHEMUMS AND POETRY |

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Much has been written about flowers and flower viewing in East Asian cultures. Man's link to nature is on the one hand intimate and on the other awe inspiring and humbling. Some of the earliest known Chinese poetry had agricultural and martial themes, but by the 7th century B.C.E. more genteel subjects began to appear: "Peach tree soft and tender,/how your blossoms grow."(1)

* The ninth month has traditionally been referred to poetically as kiku-zuki (菊月) or the chrysanthemum month. Tao Yuan-ming 陶淵明 (365-427), the most famous Chinese poet prior to the T'ang dynasty, may have been the first to write about chrysanthemums. He retired from public life to compose and to contemplate his garden. Mums appear prominently in several of his works. "I was dwelling in peace and loved the name 'double ninth.' Fall's chrysanthemums filled the garden, yet I had no means to take strong brew in hand. So I swallowed the flowers of the ninth by themselves, and expressed what I felt."(2) Li Qing Zhao 李清照 (1084-ca. 1151), one of the greatest early female Chinese poets, spoke of the Double Ninth Festival, drinking, lounging and the scent of chrysanthemums on the sleeves of her robe. During the T'ang dynasty Yuan Zhen 元稹 (799-831) wrote a wistful poem about the coming of winter in which he noted that the chrysanthemum was not his favorite flower --- but sigh, it was the last flower until spring. Nearly 800 years later Matsuo Bashō 松尾芭蕉 (1644-94) wrote his own variation on this poem: (Paraphrased) After the chrysanthemum there is only the radish.(3) * The Kokin wakashu 古今和歌集 or as it is known in its abbreviated name, the Kokinshu, is the earliest of the Imperially ordered anthologies of completely native Japanese poems - ca. 905. Number 269 in the section on Autumn is by Fujiwara no Toshiyuki 藤原敏行 (880-907):

久方の

Here 'the clouds far above' represent the Imperial Palace and the 'cluster of stars' are the courtiers. This is the first of at least ten poems centered on the emotional significance of chrysanthemums. * We could have given dozens of other examples of literary references to chrysanthemums --- not even including the oblique ones which require an astounding knowledge of the language and culture. You can bet that each and every educated Japanese during the Edo period would have known these works. They became integral parts of their sense of refinement. The proof is rife with the connections between the great Kabuki actors and the world of poetry. Many of them even had their own poetic noms de plume. Therefore, one can easily draw the conclusion that the choice of this mon was more than just decorative and operated on many different levels. This is as true when it comes to the multitude of other symbols found in Japanese prints as it is in the iconographies of every other culture. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

(1) Quoted from An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911, edited and translated by Stephen Owen, Norton, 1996, p. 34. (2) Ibid., p. 315. (Owen points out that the term "double ninth" refers to the festival held on the ninth day of the ninth month --- obviously a most propitious moment. Owen continues to explain "To promote longevity, chrysanthemums were taken in an infusion with wine; but Tao, lacking wine eats his chrysanthemums dry." (3) Reference: Basho's Haiku, published by Toshiharu Oseko, 1996, Vol. 2, p. 317. |

||

|

|

|

Shikunshi |

|||

|

四君子 |

|||

|

The Four Gentlemen |

|||

|

|

|

|

|

PLUM |

ORCHID | BAMBOO | CHRYSANTHEMUM |

| 梅 | 蘭 | 竹 | 菊 |

| UME | RAN | TAKE | KIKU |

|

|

|||

|

The symbolic layers of meaning in Japanese culture are astounding. Shikunshi or The Four Gentlemen is a reference to four particularly noble plants: the plum, orchid, bamboo and chrysanthemum. Borrowed from the Chinese they came to represent Confucian qualities. |

|||

|

乱菊 pronounced rangiku is the description of patterns of chrysanthemums with disordered petals, especially found as mons or crests. |

HOME

HOME