JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Port Townsend, Washington |

|

TSUKIOKA YOSHITOSHI |

|

月岡芳年 |

|

つきおか.よしとし |

|

1839-1892 |

|

Subject: Tokugawa Iemitsu and Ii Naotaka on the Sacred Bridge* at Nikkō |

|

Series: "Mirrors of Famous Commanders of Great Japan" |

|

Dai Nippon meishō kagami |

|

大日本名將鏡 |

|

たい.にっぽん.めいしょ.かがみ |

|

Date: 1878 |

|

Meiji 11 |

|

明治11 |

|

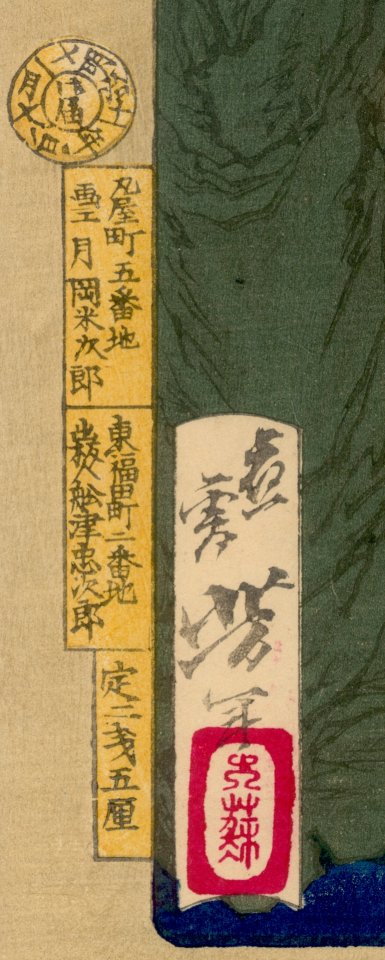

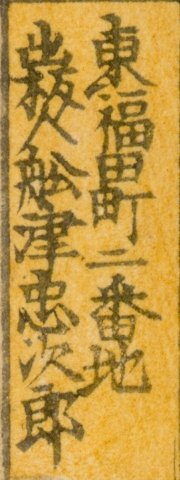

Publisher: Funazu Chūjirō |

|

船津忠次郎 |

|

ふなつ.ちゆうじろう |

|

Print Size: 14 1/8" x 9 1/2" |

|

Signature: ōju Yoshitoshi hitsu |

|

署名: 応需芳年筆 |

|

しょめい: おうじゅよしとしひつ |

|

Seal: Taiso |

|

Illustrated on-line: There is another copy of this print in the Hagi Uragami Museum |

|

Condition: Good color, printed on heavy paper, slight stain in the yellow area of the sky below the bridge. Also, some very slight staining near the top area of the water. |

|

SOLD! |

|

SHINKYŌ 神橋 しんきょう SACRED BRIDGE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Above is a great photograph of this bridge.

It has been placed in the public domain by someone who refers to him or herself as Fg2.

We are grateful to this person for the opportunity to show this. Other photos by this contributor can be found at http://commons.wikimedia.org/.

|

SEEING RED |

|

|

|

Recently a correspondent, K., wrote to me with a few ideas about why the bridge at Nikkō is red. K. wrote:

"I was browsing your web site [and]... I think I can offer some useful information regarding the question of 'why' the red bridge at the Tokugawa Tomb.'

The red color is

called ['bengara'] in Japanese, which is a corruption of 'Bengal'. This

precise shade of red is/was used on Shinto shrines, palaces (which doubled

as religious sites in ancient times, the Emperor was a 'priest-king' back

them), the color is also used on bridges and torii. So, the short answer is,

'it's red because it's a sacred bridge.'

This explanation seems more than reasonable to me and until I hear otherwise this is the one I will accept. However, it raises a few more questions in my mind. Since bengara (ベンガラ) is a name derived from the Bengal region in India rich in iron oxide soil used to acquire this particular color from the 16th century on what color did they use before that and what did they call it. Was it still a deep red, but derived from a different material?

Another question arises from something else I read a number of years ago, but for the life of me have been unable to find again to check my sources. The quote said that the red and white of the Japanese flag represented the red or female element and the white was the male. It doesn't take a stretch of the mind to understand the sexually oriented use of these symbolic colors. The contrast of the two in combination is - if this is true - a clear analogy to the yin-yang concept.

Whether or not the use of red is meant as the 'female' aspect of the universal whole the thoughts contributed by K. make a wonderful addition to this site and are greatly welcomed. Thanks K! |

|

TOKUGAWA IEMITSU THE SHOGUN ON THE BRIDGE |

|

|

|

Tokugawa Iemitsu (1604-1651 徳川家光 or とくがわ.いえみつ) was the third shogun of his line ruling from 1623 until his death.

1633: Forbade foreign travel. Banned Christianity.

1634: Began the reconstruction of his grandfather Tokugawa Ieyasu's shrine, the Tōshō-gū Shrine (東照宮 or とうしょうぐう) at Nikkō. This took two years.

1635: Established the Sankin Kotai system which meant that each daimyo or regional lord had to maintain a separate household in Edo, the shogunal headquarters. The daimyo were forced to split their time between Edo and their homes while leaving their wives and children living near the shogun.

1639: Decided that only China and the Netherlands were allowed to visit the port at Nagasaki.

1651: The only shogun to die in office.

Interred at the Taiyūin-byō (大猷院廟 or だいゆういんびょう) at Nikkō. Smaller than Ieyasu's tomb, but similar in design.

Iemitsu solidified the control established by his grandfather, Ieyasu who was one of the greatest figures in Japanese history. In fact, Iemitsu probably held greater powers than his two predecessors and created the state which would rule in relative peace and safety until 1868 when the Meiji Emperor was installed as the head of nation.

Prior to the Meiji Restoration it would have been illegal for an artist to portray Iemitsu or any other Tokugawa shogun in a historical setting. Ten years into the new era and topics which had been proscribed were now fair game. The artists' repertoires had suddenly grown at a time when woodblock printing was on the wane. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

RUDYARD KIPLING TOOK A WHACK AT MYTHOLOGIZING |

|

|

|

In 1889 Kipling left India on a trip around the world and stopped in Japan on the way. While there he decided to visit the shrine/tomb of Tokugawa Ieyasu at Nikkō. After a five hour train ride he disembarked expecting to travel the last twenty-five miles by rickshaw. However, his guide convinced him that it would be better and more comfortable to go by cart. This was a mistake. "Never go to Nikkō in a cart" Kipling said. It started out pleasantly enough. The Englishman was truly impressed. Both sides of the road were lined with eighty foot tall cryptomeria trees "...with red or dull silver trunks and hearse-plume foliage of darkest green" The sunken road was dwarfed by a solid wall of wood. The first five miles were "Glorious! Stupendous! Magnificent!" But after that spirits sagged. Had it been a warm, sunny day it would have been one thing, but it wasn't. It was cold and what had started out so nicely soon turned oppressively dreary. After another five, long, torturously bumpy hours they reached Nikkō. There they were met by a fresh wall of giant trees looming over a cascade of turbulent greenish waters splashing over blue boulders. But most remarkable of all was the elegant, bright red bridge arching gently over the ravine. At this point Kipling's description leaves the world of observation and fact for the realm of fantasy. He hypothesized that long ago a "great-hearted king" visited the site and was so taken with the natural beauty that he felt that he must do something to enhance it. It needed something --- perhaps a touch of color. But what? Gently the king tried placing a small child dressed in blue and white against the wall of dark green. An elderly beggar standing nearby saw this tender and sensitive act. He moved forward to beg for alms. Not wanting to be bothered while he was decorating the king deftly cut off the old man's head in one swift stroke. Blood gushed everywhere and some of it fell on some of the rocks by the river. That was it! This beautiful scene needed a touch of red. And that is how they came to build a blood red bridge over the river. At least, that is the Kipling version. To save people the trouble of searching out the accuracy of this story he added that you will not find this in any of the guide books.

From: Sea to Sea, Chapter XIX, "The Legend of Nikko Ford and the Story of the Avoidance of Misfortune", 1899. |

|

|

|

Of course, this is not the true story of the origins of this bridge. But that is what makes Kipling Kipling. Besides, he was never known for what we now call 'political correctness.' Then what is the true story? We are still trying to figure that one out. Hopefully, soon, we will be able to give you a somewhat more accurate account. Much of what we already read is outright contradictory. Stay tuned. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Publisher: Funazu Chūjirō |

|

Date Seal: Meiji 11 (1878) |

|

HOME

HOME