|

JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Port Townsend, Washington |

|

Utagawa Hiroshige II 二代歌川広重 うたがわひろしげ (1829-69) |

|

|

Print from the series "Edo no Hana Zukushi" (List of Beauties of Edo) 江戸の花尽くし えどのはなずくし |

|

|

Print size: 9" x 6 3/4" |

|

|

Date: 1849-50 |

|

|

Censors: Kinugasa (Kinugasa Fusajirō) and Watanabe (Watanabe Shōemon) |

|

|

衣笠 きぬがさ |

渡辺 わたなべ |

|

Print type: aizuri-e 藍摺絵 あいずりえ |

|

|

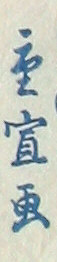

Signed: Shigenobu ga

|

|

|

Publisher: Wakasa-ya Yoichi 若狭屋与市 わかさやよいち |

|

|

$118.00 SOLD! |

|

|

花を欺く美人 |

|

**** |

|

はなをあざむくびじん Hana wo azamuku bijin "A WOMAN AS PRETTY AS A FLOWER" |

|

**** |

|

The translation of Japanese terms can be a bit confounding. For example, the title of this series is Edo no hana zukushi which can be translated as "The List of Beauties of Edo." However, the word hana can mean either "a flower" or (by extension) "a beautiful woman." This explains the pairing of the two major elements of this print.

|

|

**** |

|

両手に花 |

|

The expression shown above has a dual meaning: 1) to be doubly blessed or 2) to be a man sitting between two women, i.e., flowers. Literally it translates as having flowers in both hands. |

|

**** |

|

大和撫子 |

|

Yamato nadeshiko

or Japanese pink - the flower and not the color - also means a woman who has

all of the qualities most admired in traditional feminine virtues. In Renaissance Europe the stem of a pink or carnation was often held in the hands of a woman who was betrothed to be married. The symbolism clearly compares the fleeting beauty of bride at her best to that of a flower which eventually will fade and die. The bride's half-length portrait would always be paired with that of her husband or fiancť. |

|

**** |

|

蕾 |

|

THE VIRGIN AS METAPHOR |

|

In the West when a female loses her virginity it is commonly said that she was deflowered --- especially in the case of a sexual assault. However, in Japan a virgin is often compared to a flower bud or tsubomi. When a Japanese woman loses her virginity she is like a bud which then blossoms. |

|

**** |

|

徒桜 |

|

The above term can mean ephemeral like easily scattered cherry blossoms or it can be a fickle woman. |

|

**** |

|

姥桜 |

|

An uba is an aged woman and zakura is a cherry blossom --- hence a faded beauty. |

|

**** |

|

花魁 |

|

The term oiran which designated the highest order of courtesan in the 19th century is a combination of the word hana (花) which means flower plus the word kai (魁) which means charging ahead of others --- or the leading flower. |

|

**** |

|

花街 |

|

If women are flowers then it makes sense that the red-light district would translate literally as the flower district. |

|

**** |

|

壁の花 |

|

A shy woman is described as a wall (壁) flower (花) as in the West. |

|

**** |

|

花柳 |

|

Flower + willow = red-light district |

|

**** |

|

花柳病 |

|

Flower + willow + disease = venereal disease |

|

**** |

|

花婿 |

|

**** |

|

百花繚乱 |

|

Literally this is a profusion of flowers, but by allusion it is also a gathering of many beautiful women in one place. |

|

**** |

|

I have used a number of sources for the information listed above. Especially useful was Womansword: What Japanese Words Say About Women by Kittredge Cherry and published by Kodansha in 1987. |

|

|

There are two triptych by Hiroshige II in the collections of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco which also link women with flowers. Both are from 1857 and are entitled "A Procession of Women on a Journey of Flowers " or Hana no tabi onna gyoretsu (花の旅女行列 or はなのたびおんなぎょうれつ).

Anyone passionate for prints and paintings and unfamiliar with the image base of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco should seek it out and bookmark it. It is one of the greatest resources of its kind on the Internet. |

|

藍摺絵 AIZURI-E |

|

|

The need for a colorfast blue must have been obvious to the print makers of the late 18th century. Aigami (藍紙 or あいがみ?), an organic colorant made from the dayflower (1), faded quickly --- especially when exposed to daylight. Ai, an indigo blue, was not much better. Any collector of Harunobu, Shunsho or Kiyonaga, et al., must have been aware of this problem and perhaps just a little mortified.

This problem was finally resolved by the importation of Prussian blue (2) through the port of Nagasaki (長崎 or ながさき) in the 1820s. Roger Keyes (3) notes that one of the earliest known examples of the usage of this pigment on a Japanese print appeared in Osaka in 1825 on the cap of a flying immortal in a surimono dedicated to the retirement of Nakamura Utaemon III (三代中村歌右衛門). This deep blue color didn't show up in commercial prints in Edo until the spring of 1829 in the work of Eisen. |

|

|

|

|

|

(1) Aigami was made from the Commelina communis or dayflower of lily family. In Japanese it is called Tsuyukusa ( 露草 or つゆくさ) or rainy season plant. The beauty and intensity of this plant's flower make it understandable that artists would want to use it as a colorant. Unfortunately the color was just as fugitive as the flower itself. Roger Keyes pointed out in a paper delivered at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1999 that aigami turns greenish yellow when fading. However, he also added, that all pale colored prints are not necessarily faded. Some were printed pale as a cost saving measure. (2) Prussian blue (プロシヤ青) is also known as Berlin blue or bero-ai (ベロ藍). (3) Japanese Woodblock Prints: A Catalogue of the Mary A. Ainsworth Collection, Roger Keyes, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, 1984, p. 42, plate #140, p. 91 and catalogue entry #439, p. 185. |

|

|

To the right is a dayflower. It is from this that fugitive colorant aigami was made. It was replaced by the more colorfast Prussian blue in the 1820s. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

BY WAY OF ANALOGY... WHY THE INTRODUCTION OF A NEW COLOR CAN HAVE SUCH A PROFOUND EFFECT ON THE NATURE OF A NATION'S CULTURE. |

|

|

When I was young, because my mother thought of herself as cultured and that her children should be too, I was made aware of a specific category of ceramics referred to as blue and white. Blue and white was everywhere: delft ware, Willow Pattern, Worcester, etc. In my mind it quickly became very ho hum. It wasn't until decades later when I was studying the historical development of Chinese porcelain that I realized what an exciting moment it must have been when that particular category first appeared during the YŁan dynasty in the 13th century. The Mongol YŁan were crude ruffians by Chinese standards. blue and white became inextricably bound to that period and to those usurpers. But the Chinese knew a good thing when they saw it and by the time of the reestablishment of a native ruling class, i.e., the Ming, blue and white was fully embraced. By the 16th century the purification of the blue element, cobalt, and the refinement of pottery techniques was beginning to rival the glory days of the earlier Sung dynasty. * Although blue and white porcelains are now among the glories of the world's great museums most people hardly notice them. Stand in a room or corridor at the Met, for example, and watch the hordes walk right by these masterpieces. Like single malt Scotch blue and white is an acquired taste. * When the rarity and expense of importing East Asian porcelains meant that only the wealthiest Europeans could afford it necessity became the mother of invention. Augustus the Strong, the Elector of Saxony and King of Poland, paid huge sums for individual pieces of Chinese porcelain. This was one of his passions and it depleted his treasury enormously. That was when he decided it would be cheaper to reinvent Chinese porcelain than to buy it. The end result: Western production was off and running. In time Europeans started making cheaper and cruder knock offs and the spread of blue and white quickly caught on among the burgeoning middle class. Eventually manufacturers in China began the mass exportation of cheaper versions of what had once been available only to the Chinese emperor. According to Robert Copeland in an article entitled "Joshiah Spode and the Origins of the Willow Pattern" published in the 'Antique Collector' in 1978 much of the export ware bound for Europe was stored in the bilge water "...to act as a platform on which the more expensive and vulnerable cargos of tea were stowed..." Inspired by these pieces Spode* created the Willow Pattern which was so amazingly popular in nineteenth century England and America and is still much sought after by dedicated collectors today. Little did Spode or the original buyers know that this lovely little motif of the graceful willow had an iconographic association with prostitution in China. If the 19th century New England descendants of the Puritans had understood the symbolism do you think they would have said grace over these plates before beginning their Sunday repast? I don't think so. But all fads must pass --- even the fads which last for centuries. If you were to ask anyone under the age of 30, or maybe even 40, let alone 20, what 'blue and white' is they wouldn't be able to tell you. Of course, there might be a few exceptions, but those would only come from youngsters who had the equivalency of an education from a girl's finishing school. |

|

|

*One astute reader of this page wrote to tell me on April 28, 2005 that I had made a factual error in the text above. Originally I had stated that the Willow Pattern was produced in China and exported to the West. The reader was kind enough to point me in the right direction by sending me a link to the history of this pattern at www.spode.co.uk. There they reproduce the article by Copeland for all to read. I want to thank this correspondent and hope that more of you contact me when or if you find similar errors in these pages. |

|

|

|

|

|

On May 19, 2005 I was reading Women of the Pleasure Quarters by Lesley Downer. On page 39 she notes that in 1589 the first licensed district devoted to prostitution was called Yanagimachi (柳町 or やなぎまち) or Willow Town. |

|

To

the left is an example of Prussian blue pigment.

To

the left is an example of Prussian blue pigment. HOME

HOME