JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

formerly Port Townsend, Washington now Kansas City, Missouri |

|

|

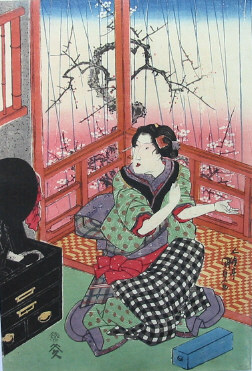

UTAGAWA KUNISADA |

|

|

|

歌川国貞 |

|

|

1786-1864 |

||

|

View of the Spring Rain |

||

|

Harusame no kei |

||

|

春雨の景 |

||

|

Circa Early 1820s |

||

|

Oban Triptych |

||

|

Signed: Gototei Kunisada ga 五渡亭国貞画 |

||

|

Publisher: Eikyudo |

||

|

|

SOLD! THANKS! |

|

|

Illustrated: 1. Catalogue of the Van Gogh Museum's Collection of Japanese Prints, by Charlotte van Rappard-Boon, Willem van Gulik and Keiko van Bremen-Ito, Waanders Publishers, Zwolle, 1991, cat. #147, pp. 132-34 2. There is another copy of this triptych in the Museum für angewandte Kunst in Vienna. This is exhibited on-line. |

|

|

|

|

THE SUBLIMINAL MESSAGE AND THEN SOME. |

||||||

|

A friend came to visit recently --- today is December 3, 2003 --- and I was showing him this triptych and trying to explain why and how it pushed my aesthetic buttons. He had brought a friend of his along. While talking my friend's friend said he had a couple of Japanese prints by Hiroshige, but didn't know much about them. I pulled out my copy of the Van Gogh museum catalogue to show him that museum's version of this triptych and to look for other examples of images of the ones he owned. That is when it struck me: Van Gogh had copied a well-known Hiroshige print which exhibited some of the same elements which so excited me about this Kunisada.

The question for me is: What did Hiroshige know and when did he know it? Is the prominent role played by the plum blossoms in the Kunisada triptych and the Hiroshiges a coincidence? Or, did Hiroshige know the triptych shown on this page and was perhaps influenced by it? I am not sure that this is answerable. Hiroshige purists would probably say "No!" and give a lot of reasonable arguments against this connection. But I am not that confident and will leave the issue open.

Below are two inserted details of prints by Hiroshige so you can judge this for yourself. |

||||||

|

Both of these examples are from Hiroshige's series "One Hundred Famous Views of Edo" |

|

||||

|

This is a detail of Hiroshige's "The Plum Garden at Kameido" Kameido Umeyashiki 亀戸梅屋舗 がめどうめやしき 1857 |

This is a detail of Hiroshige's "The Plum Orchard in Kamata" Kamata-no Umezono 蒲田の梅園 かまたのうめぞの 1857 |

|||||

|

Why is that woman playing the koto with her foot? |

||

|

|

|

|

|

One day, a long time ago, I had a couple visit me. Both very nice. He was more knowledgeable, but she shared her husband's enthusiasm for Japanese prints. While showing this triptych to them she asked the question about the foot. Immediately I reacted: "She is not playing it with her foot." I said this with a true ring of disdain in my voice. My visitor insisted and pointed at the spot. That is when I saw it: there is a child in this print being taught to play. I can't tell you how long I owned this print or how many times I had looked at it both in person and in books --- oodles I am sure --- but I had never seen the child within.

Sometimes it just takes an innocent eye.

If you are still having problems seeing it. The child is looking down and you are looking at the top of her partially shaved head, the blue area. (The Japanese adopted the use of blue to indicate the stubble of a shaved area be it a man's beard, the kabuki actor's pate or the tonsured head of a Buddhist monk or nun.) |

||

|

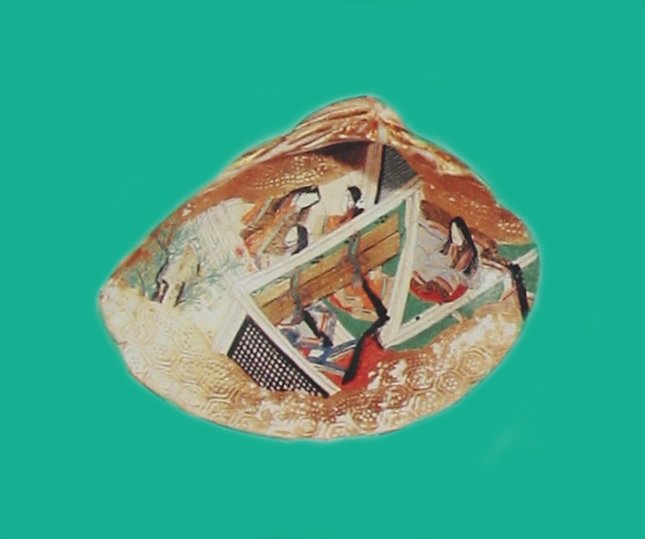

KAI AWASE 貝合せ THE SHELL MATCHING GAME |

|

|

It is a rainy, lazy day. The TV and the phone aren't working because they haven't been invented yet. Not for centuries to come. No fashion magazines, no cars, no Nintendo.

So, if you are a refined member of the upper crust seeking diversion you might perform on a musical instrument, recite poetry or play a game like kai awase or shell matching.

I wouldn't be mentioning it on this page were it not for the fact that it appears as a very subtle element of the dress of the woman in the right-hand panel --- you know, the one who is teaching the child to play the koto.

Below are several isolated examples. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

According to Saitō Ryōsuke in the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan shell matching was popular among the Heian (平安) court aristocrats (794-1185). Originally unadorned shells of various types were mixed together and the player was to find its match. Eventually plain shells were adorned with lines of poetry and/or pictures. Saitō also points out that with the decline of the court also came a decline in the game's popularity, but that kai-awase was a precursor of other games such as utagaruta (歌留多) or card matching.[1] What is striking about Saitō's description is its brevity. Perhaps this was an editorial decision at Kodansha. |

|

|

|

Mock Joya provides a lot of supplemental information. Joya stresses the use of hamaguri (蛤) as the preferred clams for this game.[2][3] He also cites a reference to this game by Kenkō (1283-1352)[4] in his Tsurezuregusa (徒然草) or "Essays in Idleness" from ca. 1329-1333.[5] Joya states that 360 shells were divided between two groups of players. Half of the shells were placed face down and were referred to as the jigai (地貝). The other half, the dashigai (出貝), were drawn from a container.[6] As a match was made that complete shell belonged to that participant. "Later, the shells were laquered or beautifully painted."[7] These evolved into the poem shells or uta-kai (歌貝). "The game of kai-awase was played by the upper class women up to the end of the Tokugawa period."[8] At the end of his entry Joya notes that during the Kyoho (享保) era (1716-36) a new custom appeared: hamaguri soup was served at weddings because each shell had only one corresponding match much, very romantically, like the bride and groom.[9]

Masahumi Sugai in Japanese Tradition in Color & Form: Pastimes states that the changeover from matching plain shells to ones with poems and/or pictures was a process of simplification. I suppose that it would be easier to make a match if you knew your poetry well. Sugai then notes that Ihara Saikaku (井原西鶴) in his "Tales of Samurai Honor" (武家義理物語) of 1688 said that the shell matching was a "...game of refinement..."[10] |

|

"As the bi-valve clam only fits its other half perfectly, it has sexual connotations and is a symbol of fidelity and true love." A new bride from the upper classes often received a game set for her dowry.[11] |

|

1. "kai-awase", entry by Saitō Ryōsuke, Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 4, p. 108, 1983. 2. Mock Joya's Things Japanese, by Mock Joya, The Japan Times, Ltd., 1985, p. 478. 3. Hamaguri shells are used for the best white go (碁)pieces. 4. Mock Joya refers to this author as Kenkō Hoshi (兼好法師). However, if you go searching for him in a library or on the Internet you might also want to look him up under these alternative names: Urabe Kaneyoshi (卜部兼倶), Urabe Kenkō (卜部兼好), Yoshida Kaneyoshi (吉田兼倶) or Yoshida Kenkō (吉田兼好). 5. There is a wonderful description of Kenkō and the "Essays in Idleness" in Seeds in the Heart: Japanese Literature from the Earliest Times to the Late Sixteenth Century, by Donald Keene, Henry Holt and Company, New York, pp. 852-67. 6. Playthings and Pastimes in Japanese Prints, by Lea Baten, Weatherhill, 1995, p. 23. 7. Joya, op. cit. 8. Ibid., this is an interesting statement which I believe to be true. However, it doesn't jive entirely with the information provided by Saitō in the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan. 9. Ibid. 10. Japanese Tradition in Color & Form: Pastimes, entry by Masahumi Sugai, Graphic-sha Publishing Company, Ltd., 1992, p. 10. 11. Baten, op. cit. |

HOME

HOME