|

|

JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

|

(No print shown on this page is being offered for sale by Ukiyo-e Prints.) THE PAIRING OF LIONS AND PEONIES IN JAPANESE PRINTS

When I was little my mother recited a poem to me that went something like this: I saw a man upon the stair. I saw a man who wasn't there. I saw him there again today. Gee, I wish he'd go away.

In the 19th century Gustave Courbet, the great French realist painter was asked to paint an angel for a church. His response: "I have never seen angels. Show me an angel and I will paint one." If Leonardo, Raphael, Tiepolo and Delacroix had felt the same way we would all be that much poorer.

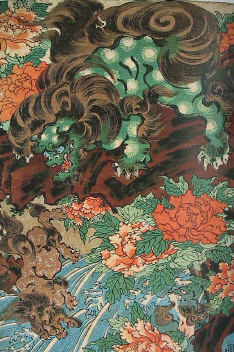

I don't know if there were any Japanese Courbets who begged off representing things they could not see. But like the man upon the stair there were no real lions in China or Japan. There was no physical model on which to base the imagery even though the lion was adopted as a Buddhist symbol of power and protection.

How then did the representations come to look so much more like a Pekinese with a perm than the regal king of beasts? I can not answer that. It would only be speculation. Nevertheless, in time one of the most common motifs showed squat little lions with decorative tufts of white swirling fur covering their bodies while they gamboled among huge peonies --- and occasionally chased butterflies. How threatening is that? It is certainly more reminiscent of Ferdinand the Bull than anything else. Cultural anthropologists have pointed out that when Christian missionaries tried to translate the Bible into native languages they were often confronted with the difficulty of describing such things as the Cedars of Lebanon to people who lived in the tundra. Huge trees became enormous shrubs for populations which had never seen a forest. Describing lions to people who had never seen one must have been the same thing. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

One of the visitors to our web site sent me this example of a tsuba which he owns. It shows two lions gamboling near the upper and lower edges. But where are the peonies? Go to the bottom of this page to find out.

PRIVATE COLLECTION SWITZERLAND |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

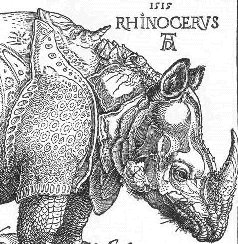

| DÜRER'S RHINOCEROS |

|

|

It should come as no surprise to anyone who has visited a zoo, read the National Geographic or traveled through one of those phony drive-through nature habitats that Albrecht Dürer never really saw a real, live rhino. Just look at the detail of his famous woodcut above.

Early in the sixteenth century an Asian potentate decided to send the gift of a rhinoceros to the King of Portugal. Surely he needed one. It caused quite a stir at the time. One man saw and sketched the animal and then wrote to Dürer with a description. Based on this the great German master created his woodcut.

WHAT DOES THIS HAVE TO DO WITH LIONS?

As we noted above no Chinese artist or craftsman ever saw a live lion as far as we know. They had to rely on Indian imagery and descriptions for their creations. For centuries all that most Europeans knew of the rhinoceros was Dürer's print. Likewise, the Chinese and Japanese had to rely visually on what in judicial terms is referred to as "hearsay" and is not admissible as evidence in court. What's a fellow to do? |

|

|

There are a number of different Japanese terms for peony. One is kaō (かおう or 花王) which translates as "king of flowers." Another is shaku (しゃく or 芍) which by itself means peony. This can be combined with yaku (やく or 薬) which means medicine, but together they translate as peony.

The character 牡 or bo (ぼ) means male, but combined with 丹 or tan* (たん) results in tree peony. |

||

|

*丹 by itself is pronounced ni. |

|

JUST PLAIN LIONS WITH PEONIES |

|

SHAKKYŌ THE STONE BRIDGE |

|

|

|

Shakkyō has an ancient tradition which has been adulterated or evolved through the years. Of Buddhist origin it tells the story of the pilgrimage of the priest Jakushō to Mt. Wutai (五台山) in Shanxi Province in China. One of the holiest sites in East Asia it became a magnet for Japanese monks and "...was associated with the paradise of the bodhisattva Manjuśri..."

"At a stone bridge crossing a deep ravine on the slopes of the holy mountain, Jakushō's is greeted by a shishi, a kind of mythical lion, auspicious messenger of the bodhisattva, who frolics and dances among blooming peonies. A version of the story appears in Konjaku Monogatari, an early twelfth-century collection of tales and is also the theme of several medieval Nō plays. Popular adaptations of what is essentially a 'lion dance' were popular from the seventeenth century onward." |

|

|

|

Source and quote: The Actor's Image: Print Makers of the Katsukawa School, Timothy Clark, Osamu Ueda and Donald Jenkins, Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 118. |

|

|

|

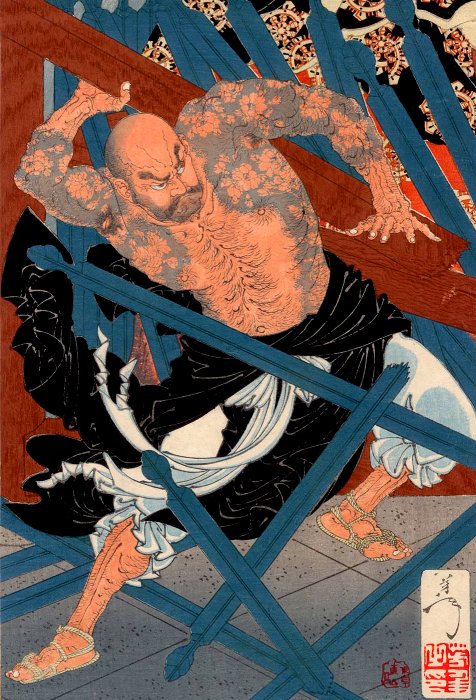

Detail from the lower half of a vertical diptych by Yoshitoshi. This image was sent to us courtesy of our friend Mike. Thanks Mike! |

|

|

|

In chapter two of The Bandits of the Water Margin a military captain kills a butcher who has assaulted his own mistress. Forced to flee he goes to Mt. Wutai and becomes a monk, but he is more a monk in name than in practice. In time he gets rip roaring drunk and attacks the monastery there. That is what is happening in the image by Yoshitoshi shown above.

We mention this because of another section on this site which we are currently developing. It is called "Bad Boys and Their Tattoos" and while the figure above shows neither lions nor peonies there is nevertheless a cultural link between the subject of this commentary and that of a literary classic which sets the scene is the same location. This was too strong a thread to ignore.

If you would like to see what we are doing on our tattoo pages - the first of which uses a detail of the strongman's tattoo - then click here: BAD BOYS AND THEIR TATTOOS. The full image of the rampaging monk is not yet posted there, but will be soon. We're working on it. |

|

We hope to add more information to this section in the next few days. Today is December 27, 2005. |

|

ANDO HIROSHIGE (1797-1858) |

広 重 |

あ ん ど う ひ ろ し げ

|

|

|

UTAGAWA KUNIYOSHI (1797-1861)

Detail of a print of a mother lion tossing her cub into the canyon. |

芳 国 |

く に よ し |

|

|

LION DANCES WITH PEONIES |

|

花笠音頭 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Above is a large detail of a print by Bunchō of the actor Segawa Kikunojō II performing a lion dance ca. 1770. This was sent to us from our friend Mike.

Thanks Mike! |

|

|

TORII KIYOHIRO (fl. 1751-1763) Detail of a print of Nakimura Tomijuro I in the dance "Hanabusa Shujaku no Shishi." |

清 広 |

き よ ひ ろ |

|

|

SUZUKI HARUNOBU 1725-1770

Ca. 1769-70 |

春 信 |

は る の ぶ |

|

|

KIYONAGA (1752-1815) |

清 長 |

き よ な が |

|

|

UTAGAWA TOYOKUNI III (1786-1864)

|

豊 国 |

と よ く に |

|

|

NIWAKA FESTIVAL IMAGES |

|

KITAGAWA UTAMARO (1753-1806) |

歌 麿

|

う た ま ろ |

|

|

UTAGAWA KUNISADA (1786-1864) |

国 貞 |

く に さ だ |

|

|

UTAGAWA KUNIYOSHI (1797-1861) |

芳 国 |

く に よ し |

|

|

LIONS & PEONIES ON SCREENS |

|

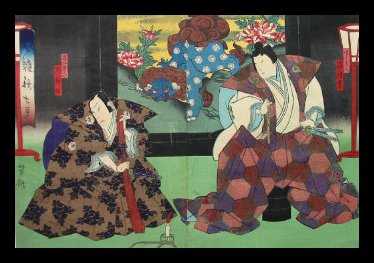

UTAGAWA TOYOKUNI III (1786-1864)

4th Month, 1859 |

豊 国

|

と よ く に

|

|

|

UTAGAWA YOSHITAKI (1841-1899) Detail of lion and peony screen in the background of a scene from the kabuki play Iro Kurabe Aki no Nanakusa Ca. 1867 |

芳 |

よ し た き |

|

|

KIMONOS DECORATED WITH LIONS & PEONIES |

|

CHOBUNSAI EISHI (1756-1829) Detail of a kimono decoration. |

栄 之 |

え い し |

|

|

UTAGAWA KUNISADA II (1823-1880) We changed the attribution on this page from Toyokuni III to Kunisada II on 8/8/08. We also changed the graphic to a larger image.

|

国 貞

|

く に さ だ

|

|

|

TATTOOS OF LIONS & PEONIES |

|

UTAGAWA KUNIYOSHI (1797-1861) |

芳 国 |

く に よ し

|

|

|

UTAGAWA KUNISADA II (1823-1880)

Detail of tattooed back of

Danshichi Kurobei. |

二代国 貞 |

く に さ だ

|

|

|

TOYOHARA KUNICHIKA

(1835-1900) |

国 周 |

く に ち か |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

There they are...the peonies. Beautiful aren't they. Thank you anonymous contributor. We appreciate your generosity.

PRIVATE COLLECTION SWITZERLAND |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

.jpg)

HOME

HOME