JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

| Port Townsend, Washington |

BAD BOYS AND THEIR TATTOOS:

TATTOOS IN JAPANESE PRINTS

BUT FIRST FOR THE GIRLS

THE BOYS WILL FOLLOW SHORTLY

|

None of the examples shown on this page or future tattoo pages is for sale - unless specified otherwise! |

|

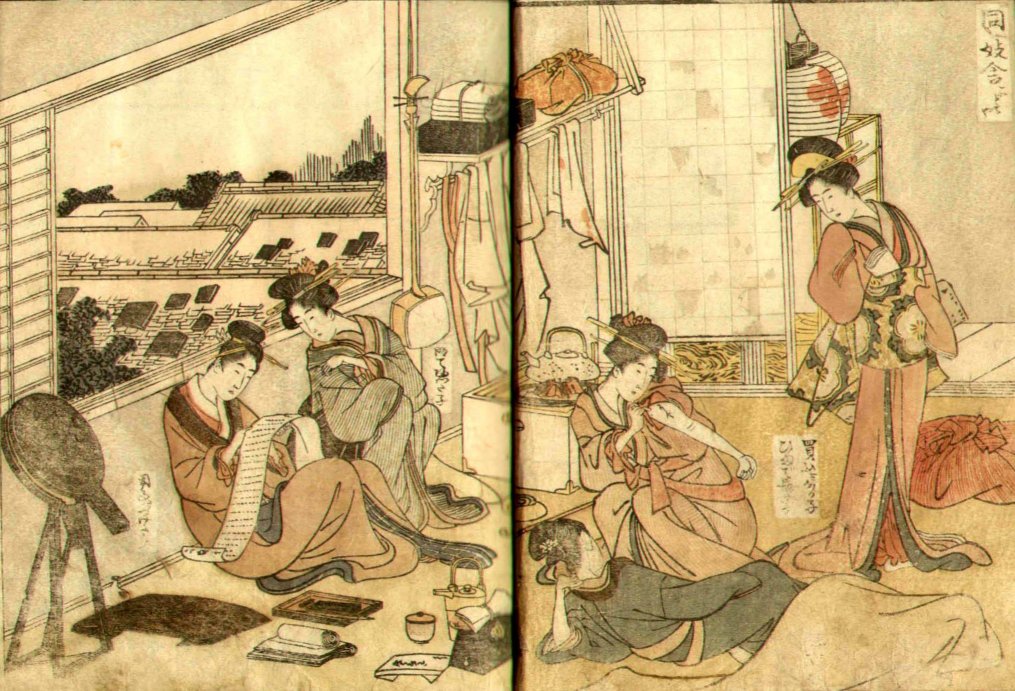

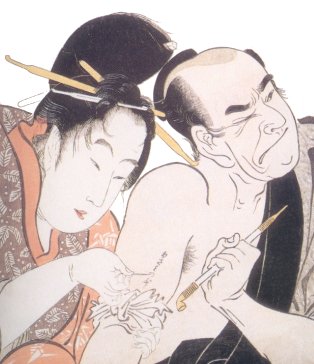

ISN'T IT IRONIC

that the earliest image I could find of a tattoo in Japanese woodblocks appears on the arm of a woman, a courtesan, who is showing off the name of her lover to her companions? After a fair amount of searching I consulted an expert on ukiyo prints and he sent me this example from an 1802 edition of Toyokuni I's illustrations for the Ehon Imaya sugata (絵本時世粧 or えほんいまようすがた) 'Picture Book of the Forms and Figures of Today'. Jack Hillier refers to this two volume set as Toyokuni's "finest achievement in book form" with the exception of his books of actor prints. The text states that the subjects represent "All types of women, from the noblest to the lowest class, virtuous or immoral..." Volume one is devoted to the ladies of virtue and volume two to the other side of the tracks. Naturally our image appears to be from the latter grouping.

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

A BURNING NEED

There is a print by Utamaro from ca. 1802 entitled "The Inept One" (Fudekashi-mono - 不作者 or ふでかしもの) in which a "...courtesan had the name of the man with whom she made a lover's pact tatooed onto her arm. But now the affair is over, and the picture shows her trying to burn the tatoo out with moxa." There are three known copies of this print. One is in the Cincinnati Art Museum, another in the Chazen Museum of Art and the third in the Takahashi Seiichirō Collection.

Quoted from: The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, text volume, p. 117. (The spelling 'tatoo' and tatooed' in the citation above is listed in the Oxford English Dictionary as an obsolete form of 'tattoo'.) |

|||

|

|

|||

|

In a 1994 article by Lawrence Rogers he discusses the Shikidō Ōkagami (色道大鏡 or しきどうおおかがみ: ca. 1680) or 'Great Mirror of the Erotic Way' by Hatakeyama Kizan (畠山箕山 or はたけやまきざん: 1624 or 26 to 1704). Kizan lists 6 shinjū* (心中) or 'sincere proofs of true love' "...in ascending order of gravity: tearing off a nail, the vow, hair-cutting, tattooing a lover's name, cutting off a finger, and piercing the flesh with a blade tip." [The italics and highlighting are mine.]

Tsume-hanashi is tearing off of a fingernail.

Kami-kiri (かみきり) - cutting off all or part of the hair.

In The Life of An Amorous Man by Ihara Saikaku two grave robbers are confronted after digging up the remains of a beautiful young woman. They did this so they could harvest the hair and fingernails to sell to prostitutes in the pleasure quarter. When asked why they would do such a base thing they responded: "It is this way. When courtesans pledge their fidelity to a favorite patron, they usually clip off strands of their hair and fingernails too and let the favorite keep them as a kind of momento..." The man who caught them knows this asks "...but what has that to do with the dead woman's hair?" Since beautiful women have many suitors this way they can dole out the hair and nails to unsuspecting dopes who won't know the difference and will think that they are special. Besides, for the grave robbers such work could be quite lucrative.

Yubi-kiri (指切り or ゆびきり) is the cutting off of a finger of a finger joint. [I am not absolutely positive about the Japanese for this practice because today 指切り means' linking fingers'. However, 切 by itself means 'to cut'.]

Kiseru-yaki (煙管焼 or きせるやき) branding with embers from a pipe.

Later Rogers quotes a passage from Yorozu no Fumihōgu (万の文反古) by Ihara Saikaku (井原西鶴 or いはらさいかく: 1642-1693). In it a prostitute laments all of the sacrifices she has gone through to prove herself to her faithless lover: wrote 13 pledges of love in her own blood, cutting her hair so short she was unable to put it up, scorched her thigh with her pipe, pulled out fingernails, cut off her little finger, wrote her lover's name 1,000 times a day for 3 months and "...I had your name and age, twenty-seven, tattooed on my left elbow..." Here, at least, there were only six categories of shinjū, but Santō Kyōden (山東京伝 or さんとう.きょうでん: 1761-1816) listed thirteen including drinking blood.

Keppan (血判 or けっぱん) is a "blood oath" or "blood seal"

Cecilia Segawa Seigle in her great book on life in the Yoshiwara said on page 192: "Women who wanted to make a more personal declaration of genuine love for her client/lover or secret lover could have his name tattooed on her arm without his knowledge. Although tattoos were considered inelegant and high-ranking courtesans avoided them, there were enough demands for them to warrant professional tattooers nearby. But to make it more sincere and private, most courtesans tattooed themselves. In later years, a courtesan would have her lover write his name on her arm, trace it with a knife, and pour black ink into the incision. Pictures were not tattooed as testaments of love: tattoos of lovers always consisted of characters to form words, brief expressions (For Life, for instance), or names."

Kazin wrote: "The standard method of tattooing is to have the man the prostitute fancies write it out, and then have it tattooed on her skin. The tattoo is cut into the skin either with a razor or a needle. In the case of the razor, the characters are ill-defined, whereas those made with a needle are attractive."

Kazin said there were two schools of tattooing. The first inserts the ink with the jab and the second jabs, wipes away the blood and then inserts the ink. Tattoos are darker where the ink has been inserted more than once.

Kazin: "Since ancient times the Sinograph inochi 命, 'life', has been written after the lover's name and is so written today. This is meant to symbolize the idea that the beloved is loved more than life itself and will be loved as one lives, which would seem to be amateurish in the extreme."

Seigle continued: "In the previous century, Kizan had criticized a tayū in Kyoto who, for the sake of originality, had all her patrons' names tattooed between her fingers. He condemned such behavior as inelegant and indiscreet." Later Seigle noted: "The value of a tattoo as a love token was, of course, that it was indelible, or so it was believed. Kizan, however, refers to the erasing of tattoos, though he does not explain how this was accomplished." In 1655 one account said that a courtesan Sanseki was expert at erasing her tattoo and "...she had changed the name on her arm seventy-five times." (Ibid., p. 193) Actually one way of getting rid of a tattoo was burning it away with a moxa treatment. Yeow!

*For all you smarties out there who think I have made a mistake... Well, I haven't - at least not this time: In contemporary parlance shinjū means lovers' double suicide, but Rogers has noted that over the centuries the definition has morphed. "...the word shinjū today is popularly taken to mean the double suicide of lovers or multiple suicide, usually of a family. This contemporary meaning, however, came into use some twenty years after Shikidō Ōkagami was completed. In Kizan's time the suicide of lovers was apparently not yet widely known as shinjū, but as shinjūshi 心中死, or shinjū death. Kizan thought that double suicide was a base act and hence not a shinjū, as he understood it. For him the ultimate act was cutting off one's own finger to prove devotion. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

According to Kizan only prostitutes would get a tattoo. Respectable women wouldn't because they weren't entertaining many men at the same time and hence had less reason to prove fidelity to one man.

Another expression for tattooing is horiire (掘入), 'dig and insert', which is "apparently an Osaka term."

The dot tattoo or irebokuro (入贅 ). This reference is from footnote 96 of the Rogers paper quoting W.R. van Gulik: "...'inserted mole'. Initially this was apparently a specific kind of tattoo: 'a dot on one of the hands halfway between the base of the thumb and the wrist, such that when the man and woman in question would hold each other's hand... the tip of the thumb would be adjacent to the dot.' "

"The practice of irebokuro first seems to have made its appearance in the Kansai region, having its origin in the pleasure districts of Kyōto and Ōsaka, around the second half of the seventeenth century, and was later taken over in Edo, where it soon developed from the tattooing of a dot on the hand to the tattooing of names or appropriate short texts of a few characters on the shoulders or arm." (Van Gulik, p. 25)

"According to Tamabayashi, irebokuro still appeared to be existing after the Meiji period among the lower grade harlots (yujō) in the harbour cities of Toba and Shimoda." (Ibid.)

Kizan says that of all the shinjū "The fact remains that tattooing is the most amateurish..."

Kizan noted that prostitutes were not the only ones to tattoo themselves: "Tattooing is not limited to cases of single-minded love. Types such as footmen, carters, and boatmen will have their crests inscribed on themselves, an act they undertake on their own accord with no encouragement from others. Some derive pleasure from having the seven-character invocation to the Buddha [南無妙法蓮華経 or なむみょうほうれんげきょう: the Nichiren sect invocation], the six-character name of the Buddha, or a likeness of a string of thirty-six prayer beads tattooed on their shoulder. Can we say that these tattoos are stupid and petty? And yet although it is foolish to derive pleasure from inscribing the name of one's beloved, can we say this practice is base? And can we say that it is shrewd to have oneself tattooed as a ruse to achieve salvation?" |

|||

|

|

|||

|

BUT WITHIN A FEW YEARS

Toyokuni I had also published an image of a figure with a name tattooed on an arm, but this time it was that of a man. I believe it dates from the early 1820s.

This is interesting for two reasons: First - the artist has mimicked the earlier example shown above of a woman displaying her lover's name tattooed on her arm and secondly because Toyokuni I is the teacher of Kuniyoshi whose art is credited with making tattooing popular among a large section of the Japanese population and is still valued among a large number of people worldwide today. Surely, Kuniyoshi was aware of the work which preceded his. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

IT IS ALSO IRONIC

that the only other image of a woman with a tattoo which quickly comes to mind is a print by Yoshitoshi called "Looking in Pain: The Appearance of a Prostitute of the Kansei Era". Doubly ironic. Published sixty-six years after the image by Toyokuni I it maintains an aesthetic link which is remarkably strong if not out right derivative. Spiritually Yoshitoshi was the artistic grandson of Toyokuni I and one of his greatest heirs. Toyokuni taught Kuniyoshi who taught Yoshitoshi. Nevertheless, it isn't only the generational line which binds the two artists, but it is also the pose and subject matter. Perhaps the Yoshitoshi is actually an homage to his much respected predecessor. Imagine the woman in the Toyokuni I sitting quietly in agony while the tattooist pricks her skin with his needle. Trying not to scream out loud, biting down on a cloth, her eyes filling with tears all so that she may honor her lover. That is what the Yoshitoshi offers us - the process. Just compare the two. The similarities are uncanny. |

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|||

|

|

|

WAIT A SEC! THERE IS A THIRD EXAMPLE BUT IT AIN'T EXACTLY JAPANESE |

|

|

|

|

|

|

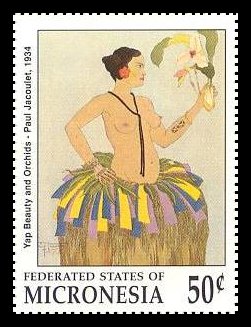

|

Paul Jacoulet, the artist of the print detail shown above, was born in Paris sometime between 1896 and 1902. The exact date is uncertain. While he was still very young his father accepted a teaching job in Japan and the family moved there. His father was called back to serve in World War I and died from his injuries. After the great quake of 1923 Jacoulet decided to devote the rest of his life to his art. His mother married again this time to a successful, young Japanese doctor. Because of this she was able to support her son, his travels and his projects until 1938. Jacoulet lived in Japan for the rest of his life - even through the wars years with their privations. He died in 1960.

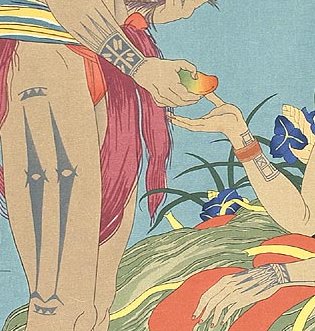

The image above was published in 1935 and is entitled "Femme tatouée de Falalap, Ouest Carolines" and was inspired by one of his trips to the South Seas. Supposedly this was Jacoulet's favorite woodblock print and is said to owe a lot to the work of Matisse. Although it is a woodblock print and was created in Japan on Japanese paper using the traditional methods - and it shows tattoos as you can see - it doesn't look very Japanese. Why should it? It portrays a non-Japanese woman designed by a Frenchman who was thinking of 20th century European avant garde artist, but still I thought it belonged here.

Actually there are at least three more prints of women with tattoos from the Caroline Islands by Jacoulet, but but their bodywork is much more subtle. There are also two images with men with tattoos from the same grouping, although I don't know if they are bad boys or not. Can't tell from the prints. |

|

|

|

I don't know if you can see it in the image, but the right hand is tattooed as is the left forearm. |

|

|

|

Above is a detail from a print by Jacoulet called "Amoureux à Tarang. Yap, Ouest Carolines". |

|

|

|

THAT EVER PRESENT RuPaul FACTOR |

|

|

|

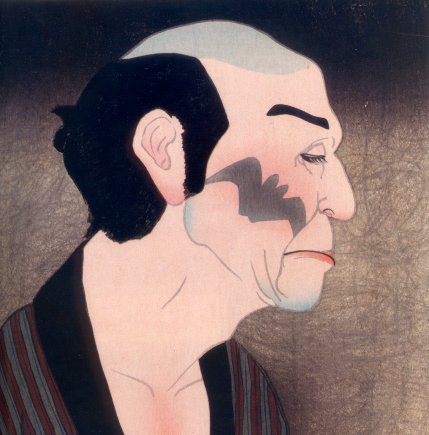

Detail from a print by Toyokuni III dated 1859. This conflicts with the information provided below about the original date of the play discussed in this section. I don't know yet how to reconcile the discrepancy. |

|

|

|

Flipping quickly through a stack of equally beautiful Japanese woodblock prints one may be forgiven for thinking that one is looking at a picture of a woman in this image. But no. This is our first truly tattooed bad boy print we have chosen to show. True, he might have the chest of a Jamie Lee Curtis, but Jamie Lee Curtis has the chest of a Jamie Lee Curtis and she is damned sexy - at least to me. Here we have the dashing, young bandit, Benten Kozo Kikunousuke who has dressed up as a woman to carry off one of his escapades. While it is true that he is only a literary character created by the playwright Mokuami that doesn't make him any less real to us. Besides we live in an age bombarded with gender confusion: Tony Curtis, Jamie Lee's real life father, and Jack Lemon donned dresses to escape bad boys who were trying to kill them - and Lemon even ended up engaged to Joe E. Brown; 6' 4" John Lithgow played a cross-dressing, transsexual, ex-jock in drag; 5' 6" Dustin Hoffman in "Tootsie"; That really tall Aussie Dame Edna is better recognized as a woman (sort of) than as a man; And don't forget the 5' 7" Julie Andrews who played a woman playing a man playing a woman. So, why not a Japanese bad boy? Besides Shakespeare wrote similar roles. |

|

|

|

"BENTEN KOZO COCKS AN IRONIC EYEBROW"

Benten Kozo (弁天小僧 or べんてん.こぞう) is our first bad boy - or, at least, the first of several we will be dealing with. How did he go wrong? Did he smoke dope. No! Did he go whoring? Yes, but so did everyone else. He was from a reasonably respectable family. That is, if a merchant's family could be considered respectable. At least his father wasn't an outlaw. But so many good kids from decent families go bad, don't they? They hang with the wrong crowd, they get tattoos... Sounds contemporary doesn't it.

Below I will try to give you a fairly concise description of this character based on the summary of the play "Benten Kozo" as laid out by Aubrey S. and Giovanna M. Halford in their The Kabuki Handbook published by Charles S. Tuttle Company in 1990 (pp. 11-16).

The play was written in 1862 as a vehicle for the nineteen year old actor Onoe Kikunosuke V (尾上菊之助 or おのえきくのすけ). Our hero-cum-bad boy is the son of a wealthy cloth merchant. As a boy his father placed him in the service of a man of a distinguished rank, but he is caught stealing and runs away. Calling himself Benten Kozo Kikunosuke he survives by preying on the vulnerability of the pilgrims at two of the major temples in Kamakura. This was made easier because not only was he extremely handsome, but also because he was a good actor. Could there be a better combination for a con artist?

Act I (Before the Hatsuse Temple)

Benten Kozo appears disguised as the deceased young samurai Shinoda Kotaro accompanied by one of his cohorts, Rikimaru, who is posing as his servant. [Bad boy act #1 - the con job]

Shinoda Kotaro's fiancé, the Princess Senju, comes to the temple to pray for her lovers soul. Although they were engaged they had never seen each other. The princess notices the handsome young man and sends one of her maids to find out who he is. When she is told who he is said to be she is overjoyed.

She asks B. K. what he is doing there and he says that he is in hiding and begs her not to tell anyone. She thinks he is actually hiding so he won't have to marry her so she grabs his sword and tries to kill herself. B. K. stops her and leads her to a local teahouse where he can prove his love. They do it - or, at least, I think they do. [Bad boy act #2 - seduction of a vulnerable princess through deception]

While all of this is happening a young man runs out of a temple having stolen a large sum of money. He is pursued by the men he robbed. They catch and beat him and get their money back. Then they go to a teahouse where they are robbed again by the servant of the first thief. The second thief wants to return the stolen the money to the first thief. [Are you still with me on this one?]

B. K. and the princess leave the teahouse and she gives him an incense burner and begs him to take her to his home. "Benten Kozo cocks and ironic eyebrow at his comrade Rikimaru. Then, taking the girl's hand, he leads her down the hanamichi. [The hanamichi is the raised walkway that passes through the audience in a kabuki theater.]

Act II (In the mountains.)

B. K. and the princess stop at a shrine and he tells her who he really is. "...overcome with shame that she should have given herself to a criminal, flings herself over a cliff." A monk from the shrine overheard the whole conversation and demands that B. K. give him the incense burner. B. K. refuses and the two men fight. [Bad boy act #3 - brawling] The monk wins and B. K. begs him to kill him. The monk refuses and forces B. K. to join his outlaw gang as a blood brother. Obviously he wasn't really a monk.

The first thief - remember him - who is about to kill himself stumbles on the body of the princess and discovers that she was only stunned by the fall. She recovers and they tell each other their personal stories. It turns out that the first thief had been the servant of her dead fiancé. When she hears that she finally succeeds in killing herself. [At least we don't have to deal with her anymore.] The first thief goes back to his original plan to commit suicide when the second thief show up and gives him the money he stole. They decide that thievery can be profitable and preferable to death so they dedicate their lives to crime. They too become blood-brother members of the so-called monks gang.

|

|

Detail from a print from 1864 by Kunichika showing a disheveled Benten Kozo.

Note the subtly exposed, tattooed upper arm of the actor. |

|

Act III Scene 1

The monk/gang leader has a third persona - that of a respectable samurai, but his neighbors suspect that he has connections with the criminal underworld so he sends two of his thugs out to rob a nearby shop. Then the gang leader/fake samurai will show up and apprehend the thieves and win everyone's respect again - plus a probable reward. The shop they choose is the one owned by B. K.'s real life father. Dressed as a high-ranking young lady [see the images above and below] B. K. and his buddy go into the shop. B. K. pretends to steal a piece of cloth and there is a scuffle. His buddy proves that the cloth is not from that shop and produces a receipt from another business. B.K., aka the young lady, is slightly injured on 'her' forehead and her 'servant' demands compensation. After much arguing the owner pays up. [Bad boy act #4 - extortion] That is when the monk/gang leader/respectable samurai shows up and uncovers their deception. B. K.'s father "...has caught sight of a pattern of cherry blossoms tattooed on the lady's shoulder and believes she is a man in disguise." "This is the great moment of the play." B. K. owns up but his father doesn't recognize him even as he begins removing his costume.

The monk/gang leader/fake samurai offers to behead the two scoundrels, but the father thinks that would be bad for business and wants to forget the whole affair. He gives his son money for medicine to treat his wound and B. K. "...kilts up his woman's clothes and he and Rikimaru go off."

Scene 2

The monk/gang leader/faux samurai gets drunk with the father and tries to rob him after telling him the truth. Threatening to kill the father his shop manager/son-in-law offers to die in his stead. At that point the monk/g. l./f. s. realizes that the manager/son-in-law is his own long-lost son. The police arrive, but the gang leader gets away.

Act IV

The gang make their escape after beating the some policemen.

Act V

B. K. repents his life of crime and retrieves the incense burner which he wants to offer to a temple in memory of the princess. When he arrives at the temple gate he is surrounded by the police. "They chase him onto the roof of the gate. After a spectacular fight he drives them off..." and shouts out his story, but wishes to make amends. He then kills himself. [The story goes on from there, but....I am worn out. Sorry.]

|

|

|

|

WHICH OF THE THREE WOULD YOU ASK OUT ON A DATE?

The (doctored) detail below is from a print by Tsuruya Kokei of the actor Onoe Kikugoro VII as Benten Kozo. It was created in 1995.

Given the choice of going out with any of these three actors dressed as women which would you choose? If the choice were based on the quality of the tattoos it would be something else - hypothetically speaking - between the top and bottom examples, but then again look at that mug on the one below.!

It takes a real man to be covered with flowers. Don't you think? |

|

|

AINU THIS |

|||

|

|

|||

|

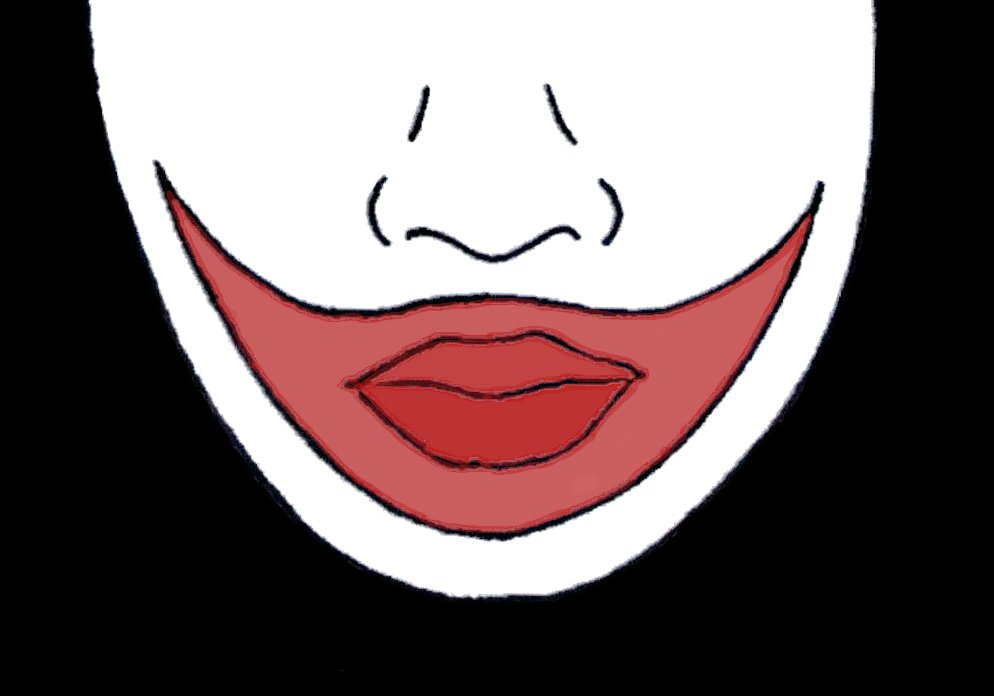

Actually I didn't. Recently I spent several hours interviewing David, a tattooist artist, who said "What about the Ainu?" To be honest they hadn't occurred to me, but I do think a few words should be added here - especially since it was only the women who were tattooed.

If you don't know, the Ainu are a group of people who are ethnically different from the Japanese. They lived mainly on Hokkaido in the north and were not conquered until the late 18th century. While there are some cross-cultural links the Ainu nevertheless remained mainly distinct. Like so many other cultures they have had long tradition of being tattooed.

"...it is generally agreed that the use of curvilinear design in the unique Ainu tattoos on the back of women's hands and around their arms was intended to protect them from evil spirits... The tattoo design was also a sign of maturity and recognized as such among adults." (1) "Similar types of tattoos were worn by early Eskimo peoples of the Bering Sea region as early as 2,000 years ago." (2)

Unlike the emphasis on tattoos featuring creatures seen on the bodies of so many Japanese in during the Edo period the Ainu never used representational animal designs in any form. To do so would have meant capturing and displeasing the spirit of the animal which was viewed as a god. This is not far removed from the beliefs of many other cultures that mirrors, photographs or illustrations captured the soul. Hence the almost exclusive use of linear and geometric patterns.

The 'beautification' process of tattooing females started when they were as young as six or seven years old and continued until they were of a marriageable age. Their lips, forearms, hands, eyebrows and foreheads were all fair game. A small cut would be made with an obsidian blade. Then soot from the bottom of a pot "...would be rubbed into the wound, followed by the application of antiseptic juice from plants like mugwort." (3)

The first tattoo a young female would receive was a small spot on the upper lip. Eventually the area around the mouth might be covered in designs which would lead to lines on the cheeks which would curve up toward the ears. (4) This got me to thinking: Why the women and not the men. Well...one reason may be in the nature of contrast between the sexes. The women had generally hairless faces whereas the men were downright hirsute. In fact, they even had a special prayer stick that they were said to be used as "mustache lifters" when drinking sake. (5)

The Japanese shogunate was disdainful of this practice of tattooing women and proscribed it. This was reiterated by the Meiji government and as a result "Today the custom of tattooing has completely disappeared." (6) |

|||

|

JUST LIKE BATMAN'S

JOKER

Although I don't have access to an image of a tattoo on the face of an Ainu woman I do have a graphic. What really struck me was the fact that when complete the area around the Ainu woman's lips looked remarkably like the makeup used on the figures of the Joker in the Batman comics and movies.

Personally I am grateful as I am sure most Japanese men were that Japanese women weren't tattooed on their lovely, lovely faces.

David Wilcox provided me with the basic design of this image. Thanks David! |

|||

|

1. Ainu: Spirit of a Northern People, edited by William W. Fitzhugh and Chisato O. Dubreuil, Univ. of Washington Press, 1999, p. 294. 2. Ibid., p. 292. 3. Ibid., p. 325. 4. Ibid., p. 326. 5. Ibid., p. 14. 6. Ibid., p. 325. |

|

WAS I WRONG ABOUT THE EARLIEST DATED TATTOO IMAGE?

YES, I WAS! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

I started thinking about a movie I once saw - "Utamaro and His Five Women" directed by Mizoguchi Kenji (溝口健二 or みぞぐち.けんじ) in 1946. Supposedly it is a modern classic, but it bored me to tears or close enough. However, there was one scene which I remember fairly well - that of a courtesan getting her back tattooed. She was known not only a great beauty but also for her skin was said to be flawless. Because she was perfection itself the tattooist was too timid to even begin the process. No image he could think was worthy or her. Utamaro saved the day by volunteering to create a design.

That started me thinking about Utamaro and tattoos. Perhaps there would be an earlier example than the one illustrated at the top of this page by Toyokuni I dated 1802. And there was. Utamaro created an image of a woman tattooing the arm of a man dated circa 1796-8.

So, I guess it wasn't so ironic after all. Oh well! As Rosanne Rosannadanna used to say: Never mind. (Sigh. Big sigh.) |

|

|

|

BELOW ARE LINKS TO THE OTHER THREE PAGES DEVOTED TO BAD BOYS AND THEIR TATTOOS

CLICK ON THE IMAGES TO GO TO THOSE PAGES

|

||

|

|

|

|

|

PAGE TWO has been removed. |

PAGE THREE |

PAGE FOUR |

HOME

HOME