|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Port Townsend, Washington |

|

|

None of the examples shown on this page or future tattoo pages is for sale - unless specified otherwise! |

|

|

THE TATTOO IN JAPAN

I may not believe in Santa Claus but Christmas came early this year when I discovered that Google had posted on-line most of Willem R. van Gulik's expert book, Irezumi: The Pattern of Dermatography in Japan. This is the volume most frequently cited by serious scholars and van Gulik's credentials are excellent to boot. He was first appointed curator of the Japanese Department of the National Museum of Ethnology at Leiden, the Netherlands, and then was its director from 1982 to 1990. He was inspired by the work of a predecessor who wrote about the namazu or giant catfish which the Japanese believed was a cause of disastrous earthquakes. I believe that he is also the son of R. H. van Gulik who wrote one of my favorite books in my library: Chinese Pictorial Art.

Van Gulik tells us that the earliest reference to tattoos in Japan is made in the Nihon Shoki of ca. 720 A.D. W. G. Aston in his translation (p. 200 of Book 1) says that during the 27th year of the reign of the Emperor Keikō on the 12th day of the 2nd month "Takechi no Sukune returned from the East Country and informed the Emperor, saying:-'In the Eastern wilds there is a country called Hitakami. The people of this country, both men and women, tie up their hair in the form of a mallet, and tattoo their bodies. They are of fierce temper, and... their land is wide and fertile. We should attack them and take it." ¶ The Nihon Shoki was written in Chinese and the characters translated as tattoo were wen (文), 'decorating' or 'embellishing', and shen (身), body. While the Sino-Japanese pronunciation would be bunshin scholars say that it should be read as mi wo modorekete. Mi refers to the body and modorekete to making dots, stippling, mottling or stiping. Van Gulik notes (p. 5) that the original ideograph before 900 B.C. in China for the character 文 was an image of a man with a tattoo on his chest. What is particularly interesting is that while the Japanese term for tattoo is irezumi (入墨) by the time of the Tokugawa period 文身, the ancient Chinese form, was also pronounced that way and now meant 'inking' and by extension 'tattoo', too. Yet, "In most cases, it appears that these characters were used to indicate tattooing as a form of punishment." ¶ At the beginning of the Meiji period (1868-1912) the characters 刺文 were used on all legal documents. After the Meiji period they switched back to 文身 and more recently to 刺青 which is also pronounced irezumi. The first character, 刺, means to stab, prick or sting while the second character, 青, means blue or green. Van Gulik is puzzled by this and wonders why they hadn't adopted the kanji for black instead. I would agree.

The oldest account of tattooing as punishment also comes from the Nihon Shoki. Aston describes an event from the year 400 when on the 17th day of the 4th month - a summer month and not our April - the Emperor ordered that Hamako, the Muraji of Azumi, be branded near the eye for rebellion against the state. The Emperor was showing leniency because Hamako could just as easily been put to death. After that such punishment was referred to as Azumi eye. Aston footnoted the term 'branded': "Literally 'inked.' The branding consisted in tattooing a mark on the face or other part of hte person. Until quite recenly criminals were branded on the arm with ink, each prison having its own special mark. Branding was originally one of the 'five punishments' of China."

In 467 the Nihon Shoki records that a man was tattooed on his face and made a bird-keeper after his dog killed one of the Emperor's birds. Van Gulik tells us that being made a bird-keeper was a demotion for the man because that was a position considered to be lower than that of even the serfs.

Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold (フィリップ・フランツ・フォン・シーボルト: 1796-1866) was assigned as physician in 1822 to the Dutch trading center at Deshima near Nagasaki. Among his many observations was the fact that penal tattooing varied according to the geographic location of the prisoner. In some areas black stripes were applied to the upper arm while in others it was the lower part. In Tamba a kanji character was tattooed to the convict's forehead. Van Gulik tells us that the character 悪 (aku or あく), i.e., evil, bad or inferior, was applied to the forehead in the Edo area in ca. 1670. By 1743 two black stripes were being used right above the left elbow. If the convict was found committing another crime a third stripe could be added. Van Gulik notes that until 1879 incorrigible members of the British military were branded with a 'BC' on their arm indicating that they had a 'bad character'. In Chikuzen province a criminal was branded with a straight horizontal line on the forehead for the first offense. For the second offense another line was added that cut through the first one. The third offense finished the character for inu (犬 or いぬ) or dog.

SO HOW IS IT THAT TATTOO AS DECORATION BEGAN?

Since branding automatically cast a person out of respectable society in that of the pariah set there was an inevitable need to 'rebrand oneself'. Traditionally there were the burakumin (部落民 or ぶらくみん) who were referred to pejoratively as the eta (穢多 or えた) and were already on the outside because they either handled the dead or were leather tanners. For them it wouldn't have mattered one way or another if they were tattooed or not. Then there were the tattooed criminals who tended to group themselves together more out of necessity or social need than for any other reasons. Members of the second lowest class, the hinin (非人 or ひにん) or non-humans, included beggars, prostitutes, wandering performers, and outlaws, but these groups could ostensibly change their ways and therefore become upwardly mobile. However, such an upward movement was extremely difficult. ¶ In Edo "...where tattooing was restricted to the arms, it happened that these minority groups gave rise to a primary innovation created by the need to camouflage these marks in some way. What happened was that figures, decorative motifs, and the like were tattooed over the mark-lines, which means that we have here one of the variables which ultimately developed into the representational tattooing. The negative connotations attached to the irezumi by society, offered to the convicted who were strengthened by their solidarity, a strong incentive to undertake intimidation and terrorization. As a result, irezumi as punishment began to have the opposite of the desired effect, was no longer applied, and was finally officially abolished in a decree, issued on the twenty-fifth day of the ninth month of the third year of the Meiji period (1870)." It should also be noted that tattooing was not a punishment which had been imposed on members of the samurai class.

The earliest form of tattooing or branding was probably related to slavery or servitude. People were branded as slaves much as cattle were branded by ranchers in the American West to delineate possession. Tattooing fell into general disuse between the time of the Taika Reformation in 645 until the beginning of the Edo period almost a thousand years later. It was in the pleasure quarters where the courtesans entertained their customers that the practice of representational or figurative tattooing first appeared, i.e., non-penal tattoos. By the late 19th century tattooing was still stigmatized by 'respectable' society. Van Gulik writes: "The association, however, of tattooing with criminals only enhanced the terrifying aspect of tattooing in the minds of the public at large. The consequent reaction of the public is therefore quite understandable, such as the example of tattooed people whose presence in a public bathhouse was the cause for other visitors to flee away in fright, especially when these people were seen to be elaborately tattooed on the arms." |

|

THE TATTOO IN CHINA

The general consensus is that the application of the tattoo in China was almost if not exclusively a form of punishment. That is what most books have stated and for that reason that is how it is viewed on the street. But there are exceptions and we will discuss them. But first I want to cite a passage from an unexpected source, Paris Inside Out by David Applefield published in 1998, in which the author talks about the contemporary Chinese community in that city. He notes that there culture is in high vogue, but has it low commercial elements that go along with this. Applefield tells us about the "Chinese men and women [who] sit outside the Center Pompidou..." and other popular tourist sites and offer to write your name in Chinese characters - Votre prénom en Chinois. The only problem is that "...most Chinese people find this calligraphy substandard, at best." Not only that but "...semi-meaningless Chinese characters pepper both Parisian clothing and skin." I would think this is probably the case in the U.S. as well. Applefield finishes by noting parenthetically that tattoos are almost non-existant in China today because of their historical association with the criminal element.

Joe Studwell in his 2003 The China Dream: The Quest for the Last Great Untapped Market on Earth makes the same point: "The curiosity of Chinese character tattoos in Europe and America leaves Chinese observers baffled and somewhat amused. The tattoos are often done by non-Chinese artists and are frequently misdrawn. The sight of Caucasians with 'Butterfly' or 'Enemy' or some such incongruous word scrawled on them is a strange one."

Tattooing was used in ancient times to brand convicts. "According to the information in the Treatise on the Norms of Punishment in the History of the Han dynasty tattooing was abolished in 167 B.C. and replaced by the shaving of the hair on the head combined with slave labour." (van Gulik, p. 7)

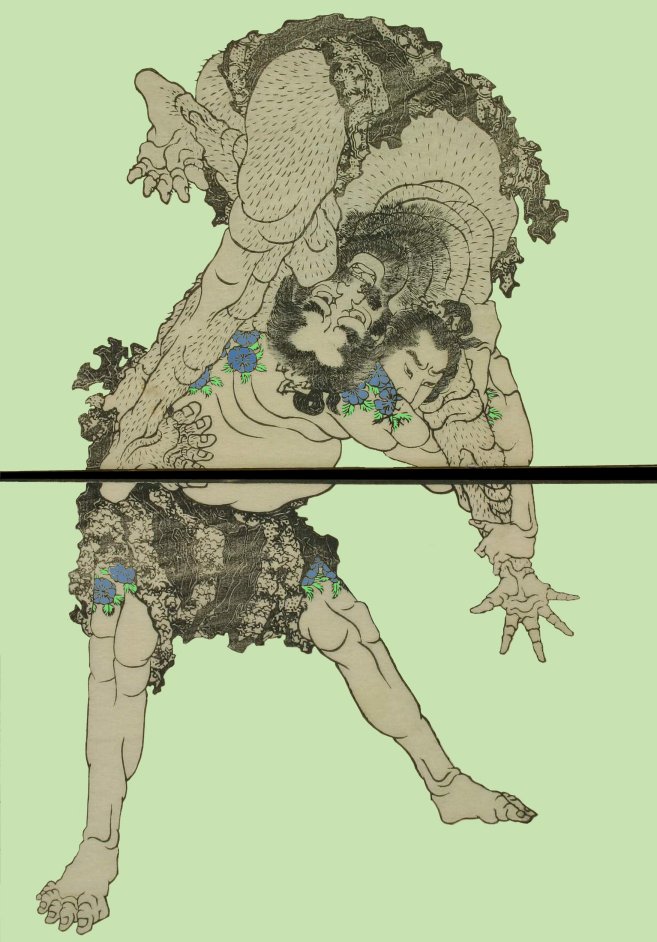

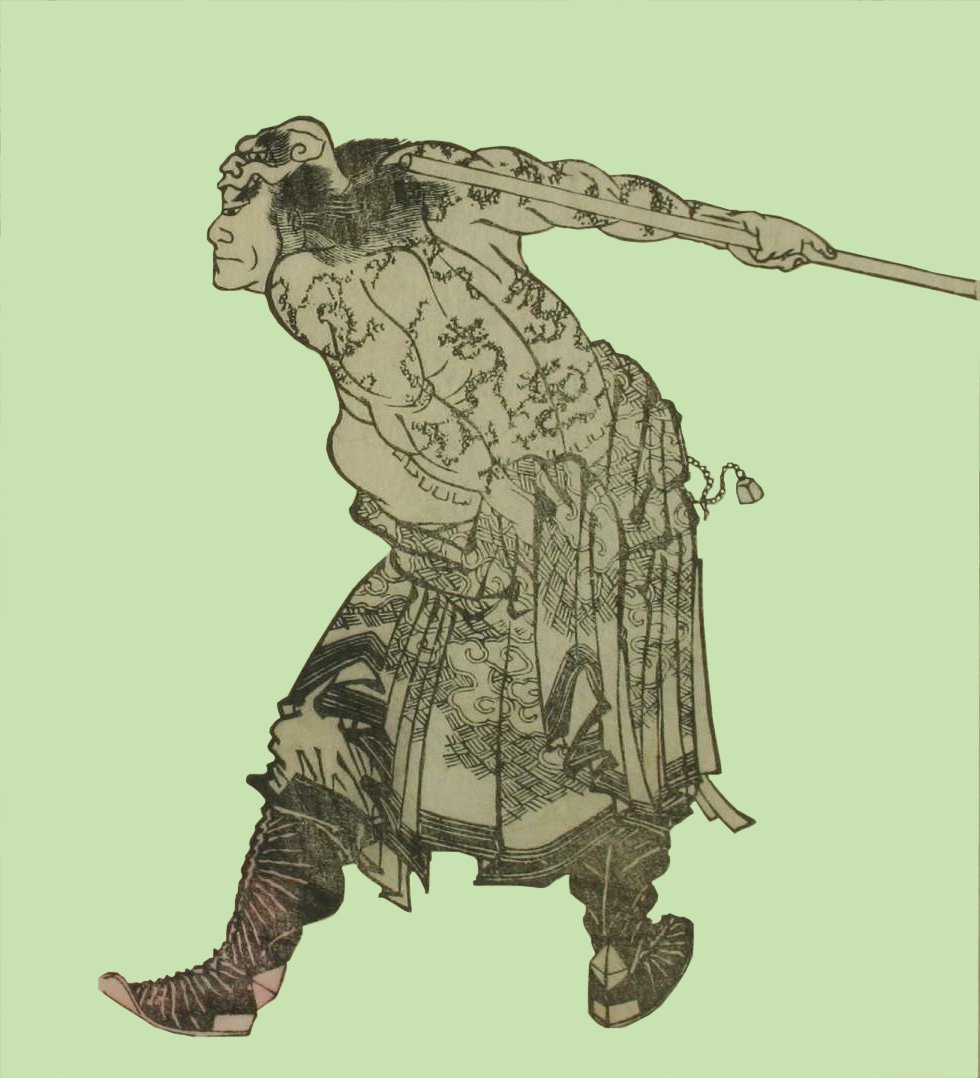

Below are two book illustrations by Hokusai to Bakin's 'Shinpen Suiko Gaden' which first appeared in 1805. They illustrate two of the outlaws of the marsh best known generally through the Japanese name the Suikoden. The first one is adorned with dragon tattoos and the lower one is clearly blossoms. (I added the color.) These predate Kuniyoshi's famous prints created decades later.

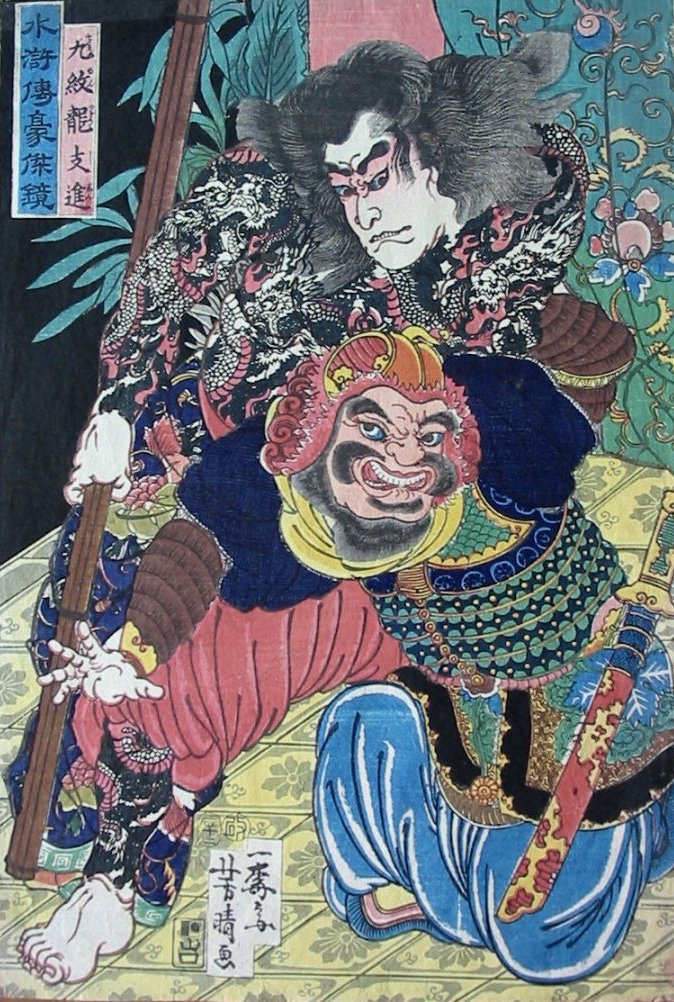

Below is a cropped version of a Yoshiharu print from c. 1854. Here the marsh bandit Kyūmonryū Shinshinis struggling with the robber chief Chōkanko Chintatsu. Compare this Suikoden figure's dragon tattoo with that done by Hokusai nearly fifty years earlier shown above. The same character is shown in the Hokuei section lower down this page. It dates from 1835.

|

|

OPPROBRIUM IN CHINA... AND EVERYWHERE ELSE FOR THAT MATTER

Somewhere in this site I am sure I mentioned that when I was a child tattoos were definitely looked down upon by almost. Only low-lifes got them or occasionally the scions of respectable families who had decided to go slumming on a drunken lark. Sailors had them and so did carnies, not to mention convicts and generally scary types. But now tattoos are almost de rigeur. Not only the children of wealth have them and many great athletes and more not so great, but also people who use terms like de rigeur. It has even been said that the future leaders of commerce and industry will be sporting visible tattoos and piercings in the board room. One U.S. senator has three tattoos: 2 visible and one a little more discretely placed. (Of course, it helps to know that he is an ex-Marine.) Boy have things changed.

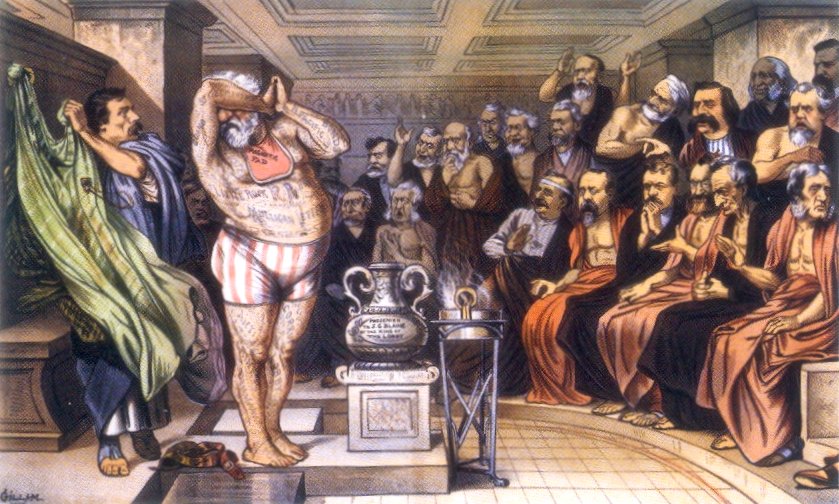

In the late 19th century James G. Blaine tried three times to obtain his party's nomination for president. He finally got his wish in 1884 as the Republican candidate. He had served in the House of Representatives and the Senate. He had even been Secretary of State in the cabinets of three different presidents: two before his run and one after. Blaine was a man with a history. He was accused of being anti-Catholic even though his mother was one and his sister was a nun. He was a big target and as such was the object of scorn in one of the most famous political cartoon ever. He was swift-boated even before there was such a term. Accused of corruption at many levels his indictments appeared etched into his skin in the "Tattooed Man". Revealed for what he 'really' was before his peers he hides his face in shame.

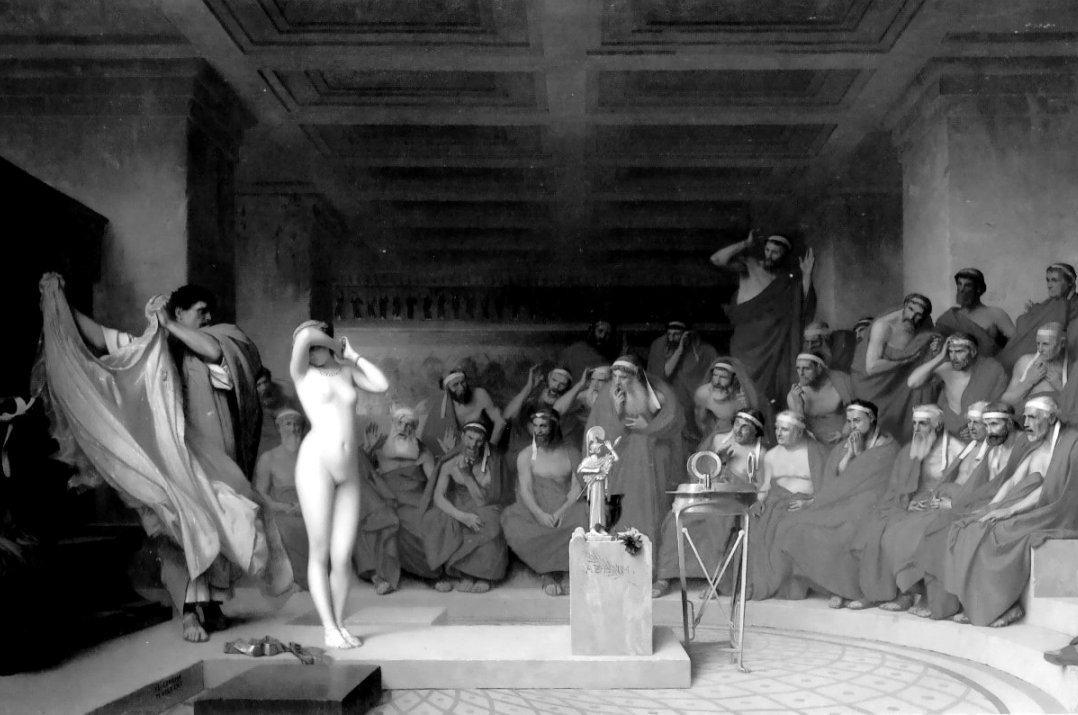

But the cartoon had a double whammy to it because it was based on the 1861 painting by Jean-Leon Gerome of Phryne Before the Areopogus shown below.

Phryne had posed for a statue of Venus by Praxitiles, the most famous sculptor of his day. As I recall, she was charged with blasphemy for presuming to believe that she was as beautiful as the goddess. Brought before a panel of judges, the Areopogus, her lawyer is losing her case. In desperation her advocate rips off her robe and declares something like "Gentlemen, judge for yourselves." They were astounded and she was acquitted. [Remember, I am doing this from memory and may not be completely on the mark.]

Phryne may have come out of this a winner, but James G. Blaine didn't. Grover Cleveland won! The tattoos may have decided the election. |

|

THE PROCESS YEOW! |

||

|

||

|

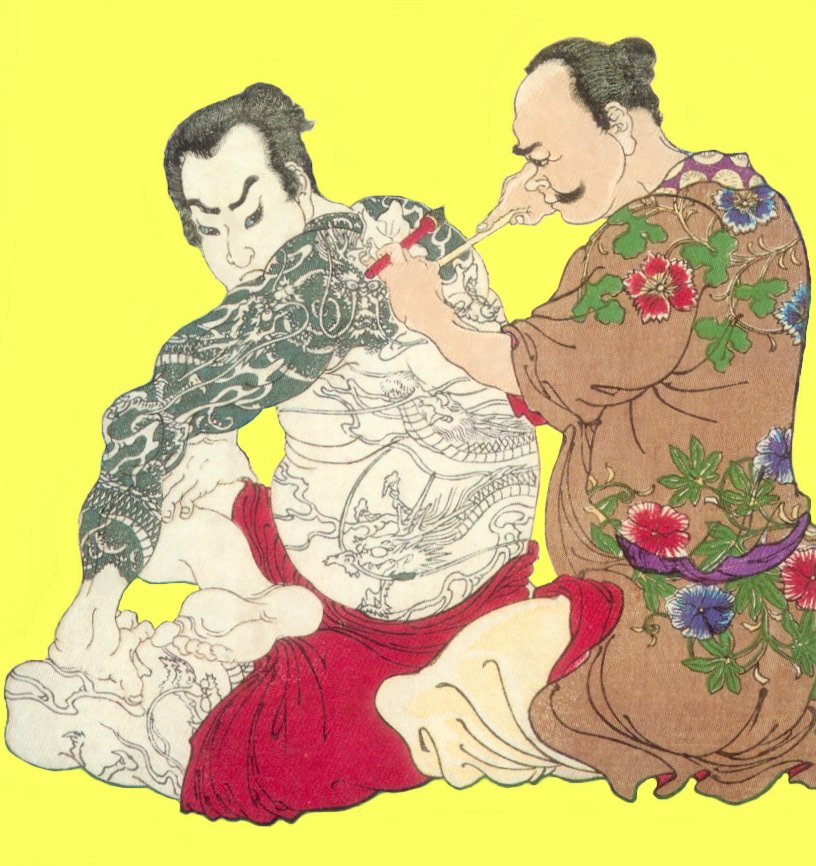

Above is a (doctored) detail from an 1868 print by Yoshitoshi showing a tattoo artist at works on one of the bandits of the Suikoden. |

|

A PIÈCE DE RÉSISTANCE A HOKUEI MASTERPIECE

THIS FOUR PANEL MASTERPIECE IS ONE OF MY FAVORITES OF ALL JAPANESE WOODBLOCK PRINT CREATIONS

THE TWO END PANELS BOTH DISPLAY ELABORATELY TATTOOED ACTORS

SNAKES & DRAGONS

DOES IT GET ANY BETTER THAN THIS? SOME MAY THINK SO. SOME MAY PREFER KUNIYOSHI SUIKODEN IMAGES, BUT I LIKE THEM BOTH!

This Osaka tetraptych dates from ca. 1835.

I HAVE A FEW QUESTIONS FOR YOU.

WHAT KIND OF MAKEUP DID THEY USE TO PAINT THE BODIES OF THESE ACTORS?

WAS THIS KIND OF MAKEUP APPLIED DIFFERENTLY THAN THE STANDARD PROCESS?

HOW LONG DID ONE APPLICATION LAST? DID THEY HAVE TO REAPPLY IT EVERY DAY FOR EACH NEW PERFORMANCE?

*** VERISIMILITUDE

If anyone out there knows anything about this technique would you please fill me in. Dean J. Schwabin his Osaka Prints (pp. 172-3) notes that these four panels illustrate a scene from a play which was never staged. So, not only does it represent a scene with two tattooed figures which never took place, but the tattoos are not really real. They are stage craft - or would have been if they hadactually shown a genuine performance.

This four-panel composition raises all kinds of puzzling issues. Although this is not the place nor the time to wrestle with them it does not change the fact that actors more than likely decorated their bodies with faux tattoos. The illustration of Benten Kozo Kikunousuke on our first "Bad Boys and Their Tattoos" page is a case in point. Click on the name above to see what we mean.

I can't help think of all of those interminable interviews with actors and directors who lament the time it took every day to put on their makeup for such movies as "Planet of the Apes" or "Star Wars". Or, were they bragging?

My friend M. gave me permission to use these prints. Thanks M! |

|

BELOW ARE LINKS TO THE OTHER THREE PAGES DEVOTED TO BAD BOYS AND THEIR TATTOOS

CLICK ON THE IMAGES TO GO TO THOSE PAGES

|

||

|

||

|

PAGE ONE |

PAGE TWO has been removed. |

PAGE THREE |

|

Any questions or comments? Please contact us. |

HOME

HOME