|

JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Kansas City, Missouri |

|

Keisai Eisen |

|

渓斎英泉 |

|

1790-1848 |

|

A Beauty Representing Contemporary Joruri |

|

Series Title: "Modern Pine Needles" |

|

当世松の葉 |

|

Tōsei matsu no wa |

|

Subject: Yūkasumi Asamagadake: Itchūbushi no hogo moyō (Mt. Asama in Evening Mists) |

|

Print Size: 14 3/4" x 10" (37.6 x 25.54 cm) |

|

Mat Size: 20" x 16" (50.8 x 40.64 cm) |

|

Date: Mid to late 1820s |

|

Signature: Keisai Eisen ga 渓斎英泉画

|

|

Publisher: Jōshūya Kinzō

|

|

上州屋金蔵 |

|

There is another copy of this print in the Spencer Museum of Art at the University of Kansas,

|

|

SOLD! |

|

|

|

One of the fascinating subtleties of Japanese woodblock prints of bijin or courtesans is that they often wear motifs which are repeated on their robes and, in this case, on a cloth in the background in the upper right corner. These are not capricious choices. Or are they? |

|

|

WATER PLANTAINS AND WISTERIA

After walking away for months from the problem of solving this design enigma I returned with a fresher approach. And voila! It doesn't appear to be a single motif, but the combination of two. Although there may have been a family that used this particular design I have been unable to locate it and until I do I will hold to the belief that this image is fanciful with no single historical association. |

||

|

|

|

|

WATER PLANTAIN MOTIF 澤瀉 Omodaka |

|

WISTERIA MOTIF 藤 Fuji |

|

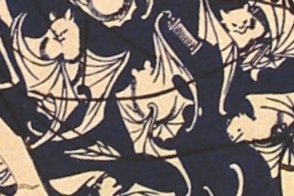

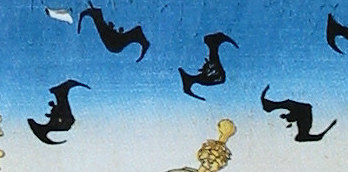

THE BAT MOTIF

Chinese is a tonal language with a many characters having the same sounds, but written with different brush strokes. As a result there are far more homophones in Chinese than there are in English or any other Western language. This allows for greater punning and what appears to us as an obtuse visual reference is easily recognizable and commonplace to the Chinese viewer. One such prominent example is the use of the characters for the sound fú which is spoken with a rising tone. Fú, meaning the word bat, is written as 蝠 while the word fú meaning happiness is written as 福. As a result the bat was portrayed in China as a substitute for the concept of happiness. The Japanese borrowed both characters for their kanji dictionaries and applied them to their own words for happiness and bat. The educated elite and eventually the general population would have known that the image of a bat on such items as clothing was a propitious symbol: may the wearer be happy. Red bats were the most efficacious --- even more than blue bats. That is the message displayed in the obi of the beauty shown above. |

|

|

|

||

|

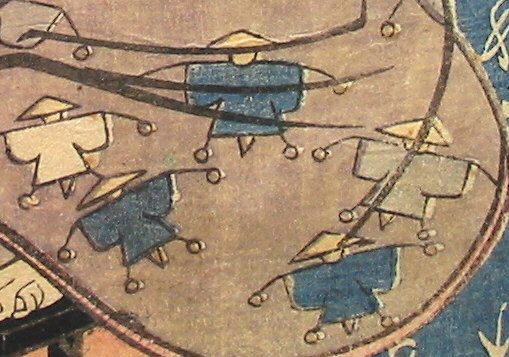

Eisen or his publishers obviously had a penchant for the portrayal of bijin wearing obis decorated with bats. Above are three such examples. The two on the right and left are instructive because they are from the same or almost identical blocks, but are printed differently. |

||||

|

One of the joys of Japanese print art is the subtleties to found upon closer examination. Above is a detail of a bath towel in a Kunisada print which I possessed for quite some time before I ever became aware of the lineless bat motif. This is not a Rorschach test (ロールシャッハテスト) or Hamlet (ハムレット) and Polonius (ポロ ー ニ アス) contemplating the shapes of clouds: this is definitely a bat. For me it is unmistakable. Perhaps it took me longer than usual to spot it because it was so overwhelmed by the other striking and beautiful details of the Kunisada print. Take a look for yourself by clicking on the image above. It will take you to that page, but note that I have turned this detail 90 degrees to the left to make it easier for the viewer to read. |

||||

|

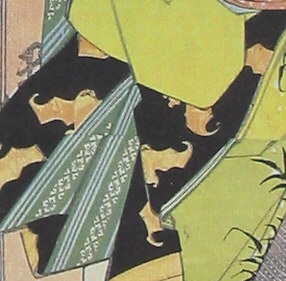

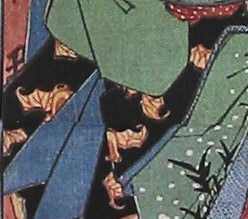

There is a very sexy print of a standing bijin who appears loosely wrapped in a robe after her bath. She is standing on and among the script of joruri texts very much like the Eisen on this page. And like the Eisen there is a subtle use of bat images as can be seen from the robe details on the right and left. These details of bats hardly seem subtle here, but when seen as only one part of a particularly exquisite print they could easily be lost as merely design elements. |

|

||

|

|

||

|

||

|

Detail of bats from a Kunisada print. |

||

|

Above is a detail from a Kuniyoshi triptych showing a bat on an actor's robe as seen from below with its wings spread. Click on the image to go to triptych and look for it in the left panel. |

Above is what appears to be a another bat viewed open winged and from below. It is very subtle, but looks very much like the form of the Kuniyoshi on the left. Click the image above to go to the full triptych by Kunisada. |

|

||||

| Above is a detail of an anonymous, late 19th century bat mon in the form of a kanji character. |

|

|

||

|

I know that many of the people who have read that bats are a symbol of happiness in the East don't quite get it. The thought of bats alone sends shivers down the spines of lots of people who just don't understand how something so horrific can be viewed as positive. Well, they have a point and the detail of the Shigenao print on the right of bats paired with spider webs should prove that. |

||

|

|

|

|||

| Detail on the right is from a child's print by Yoshifuji. | ||||

|

Detail above of a giga figure by Hiroshige in which not only is his robe decorated with bats with a bat flying above, but his hairstyle is in the shape of a bat too.

On the right is a detail of a lantern with a crest made up of three bats. This is from the same print. |

|

|

||

|

Hiroshige created many humorous and witty images on the theme of bats. Above is a detail of a man doing a kind of bat dance. |

||||

|

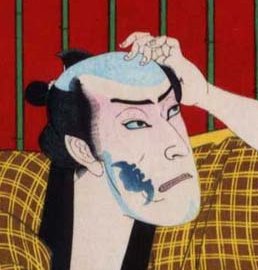

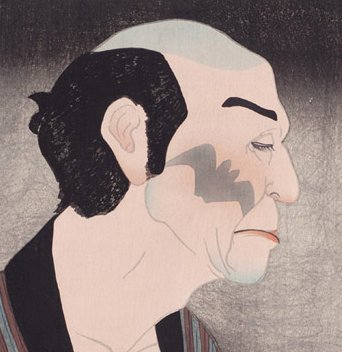

KOMORI YASU or Yasu the Bat 蝙蝠安 |

||

|

|

||

|

There is one more use of the bat in print form which I have failed to mention until now - today is December 27, 2004 - and that is an example of a bat tattoo applied to the face of a rather disreputable kabuki character. The popular play Yowa Nasaki Ukinano Yokogushi was first performed in 1853. In Act III a petty thug named Yasugoro, nicknamed 'the bat', makes his appearance. His striking right cheek has featured prominently in several Japanese woodblock prints (see below). His tattoo represents a negative contrast to the positive bat motif so frequently used by Eisen. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

|

|

Yasu the Bat by Kunisada II 1892 |

Yasu the Bat by Koka 1917 |

|

|

According to the Rietberg Museum catalogue the figure in the fan cartouche may represent the hero of a particular joruri play while the kanji script in the background are identified as the lyrics to that particular performance. Illustrated: Masterpieces of Ukiyoe from the Rietberg Museum Zurich, page 120, number 208, right hand panel. |

| As an aside: I recently realized that I had made a typo repeated several times over a couple of pages misspelling the name Rietberg. I corrected it. That led me to a search of information about the Rietberg and found out that the main building is the Villa Wesendonck which was owned by patrons of Richard Wagner. Wagner stayed there and is said to have been so smitten with his hostess that he was inspired to compose "Tristan and Isolde." |

|

A TOY STORY |

|

|

|

A WHIMSICAL TOUCH |

|

Lea Baten* notes that generically this type of balancing toy is referred to as a mamezo (豆蔵)**, but can also be called a yajirobei (やじろべえ) which is named after one of the two comic characters in Jippensha Ikku's popular novel "The Shank's Mare." |

|

*Playthings and Pastimes in Japanese Prints, by Lea Baten, Weatherhill, Inc., 1995, pp. 54-5. **I am not convinced of my research results yet. A 豆蔵 is translated as a chatter box or loquacious man. The question is: Is this the same set of kanji characters for the balancing toy? If anyone knows please contact me. One connection may be that Yajirobei was a comic blabbermouth. There is a juggling club in Japan which makes reference to this which leads me to this tentative conclusion. |

Above is a detail of a Yajirobei balancing toy motif from the robe of a young boy. The figure of the boy on this print is by Toyokuni III ca. 1854 --- the landscape element, not shown, is by Hiroshige. |

HOME

HOME |