|

|

JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

formerly Port Townsend, Washington now Kansas City, Missouri |

|

UTAGAWA TOYOKUNI III |

||

|

三代目歌川 豊国 |

||

|

1786-1865 |

||

|

Subject: "Jiraiya Goketsu Dan" 主題: 児雷也豪傑譚 |

||

|

"Conversations about the Hero Jiraiya" |

||

|

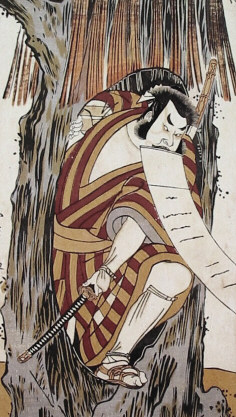

The actor in the female role may be playing a character named Princess Tagoto (田毎姫). The fellow coming out of the tree is more than likely Jiraiya himself. |

||

|

Combined Book Diptych Print Size: 7" x 9 1/4" |

||

|

Author: Mizugaki Egao 1789-1846 美図垣笑顔 |

||

|

Mat Size: 16" x 20" |

||

|

Date: Ca. 1845 |

||

|

Signed in the red cartouche in the upper left: Ichiyūsai Toyokuni ga 一陽斎国貞画 |

||

|

Publisher (possibly):

和泉屋市兵衛

Waseda University Library says 芝神明前三嶌町 |

||

|

Condition: Excellent color and condition. One small pinhole restoration in the lower right of the right hand panel. Professionally hinged and matted. |

||

|

|

print in the collection of Waseda University Library. |

|

|

Originally priced at $185.00 Now on sale for $129.00 SOLD! |

|

|

DECEPTION AND TRICKERY |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It seems that in Japanese theater and literature there is an overabundance of trickery, disguise, guile and sorcery. There are a multitude of examples. Of course, this is not limited to Japan. The West has a great number too, but the Japanese seem imbued with them.

Recently - today is February 14, 2007 - a fellow contacted me about this diptych. That caused me to look at it anew. I had already noticed the figure who is meant to be disguised as a mendicant monk held a shakujō or staff which is actually a sword, but had never considered its full significance. The meaning still eludes me and will until I know the entire story.

For more information about mendicant staffs click here on shakujō. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

In European art there are at least two different examples of people turning into trees. One is best represented by Bernini's sculpture of Daphne turning into a laurel tree to avoid the advances of Apollo and the other is "The Tree of Forgiveness" by Burne-Jones. Both very sexy. Another tree-human connection in Western art is the "Tree of Jesse" found in so many early illuminated manuscripts with a family tree growing out of that patriarch's navel. |

|

Two kabuki actors viewed within a tree. (I have no idea what this scene represents. If I find out you will be among the first to know.) |

|

On the left is a detail of an 18th c. example of a print of a man coming out of a tree. There are enough different versions of this (sub)motif to classify it as a (sub-)genre of its own.

Note that the themes using this motif vary and hence can not be seen as more than tenuously related. |

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

I only mention the examples above because of the human fascination with the nature of trees and not because there is any connection whatsoever between Western examples and those used in Japanese art. |

|

|

|

|

|

Kawatake Mokuami: "the Last Great Kabuki Playwright" (1) |

|

The Author of "Jiraiya Goketsu Monogatari" |

|

河竹黙阿弥 |

|

1816-93 |

|

|

|

Donald Keene said: "Mokuami was the last great figure of Edo Kabuki. In the opinion of many critics, he elevated Kabuki to its highest level of artistry." (2) Descended from generations of fishmongers his father broke with his past and became a pawnbroker. Mokuami was disowned early on because of his profligacy - he cavorted with geishas. After a period as a total ne'er-do-well Mokuami "got a job as delivery boy for a lending library" (3) at the age of sixteen. This period served him well later in his writing career.

Because of life's uncertain vicissitudes Mokuami became an apprentice to a major dramatist, Tsuruya Namboku V (鶴屋南北 1796-1852). By the end of his career he had written 360 plays. "Although Mokuami did not write every act, relying on assistants for much of the work, he sketched the scenarios and bore full responsibility for the whole." (4) (5)

Mokuami wrote Jiraiya Goketsu Monogatari in 1852 two years before his first great success which truly launched his career. It is probably safe to say that he revolutionized much of the stage. One of his major genres was the shiranami-mono (白浪物) which focused on lower class lowlifes such as thieves, scoundrels and blackmailers. These were the heroes of his plays and the audiences loved and identified with them. Even his love scenes were more explicit. "But Mokuami's works of violence or eroticism were tempered by their poetic language..." (6)

The introduction of the shiranami-mono was considered very bold and daring in its day. But Mokuami made other innovations which were as profoundly startling. At the insistence of the Danjūrō IX (九世代団十郎), the most prominent actor of his day, Mokuami introduced the katsureki-mono (活歴物) or 'living history plays.' Although they were never popular with the more traditionalist bound audiences. After the Meiji Restoration (明治維新) in 1868 Mokuami gave the theater world the zangiri-mono (残切物) or 'cropped-hair plays.' kabuki now included Western dress and styles, hot air balloons, modern, i.e, nineteenth century, forms of transport, social changes and current events --- albeit very inaccurately. Poetic license, I guess. Everything from military conscription to the subject of school girls was fair game. (7)

Mokuami added one other major category which is still being produced today, matsubame-mono (松羽目物) or 'Pine-tree board pieces' which are kabuki adaptations of Noh (能) theater. Among these was "Tsuchigumo" (土蜘) or 'The Ground Spider.' (Click here to see an example from this play by Kunichika.)

Keene concludes his biographical notes on Mokuami with a very succint appraisal: "One senses in his plays the corruption of the times, the petering out of a dynasty." (8) |

|

|

|

(1) The Kabuki Theatre, by Earle Ernst, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1998, p. 205. (2) World Within Walls: Japanese Literature of the Pre-Modern Era 1600-1867, by Donald Keene, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, 1976, p. 470. (3) Ibid., p. 471. (4) Ibid. (5) "Although Mokuami did not write every act..." There are some intriguing comments in scholarly writings about Ukiyo prints which parallel this quote from Donald Keene. Like so many other forms of art the end product which we experience has been made possible by a large number of people and it takes a lot of parsing to determine who made which contributions. We will be adding a commentary later on this conundrum and just how we do --- and how we just might view differently --- and are supposed to interpret the roles of the dominant players. Suffice it to note that often the artist whom we credit with the creation of a Japanese print may only have provided a loose sketch and may not have been as fully involved as one might think. (6) Ibid., p. 472. (7) "Mokuami", Kodansha Enclyclopedia of Japan, entry by Ted R. Takaya, vol. 5, 1983,pp. 234-5. (8) Op cit., p. 474. |

|

|

|

Mokuami only took the name by which we know him today in 1880. Prior to that he had been known as Kawatake Shinshichi. |