JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

| Kansas City, Missouri |

|

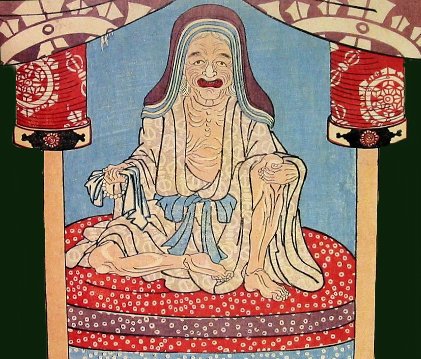

UTAGAWA KUNISADA II 二代歌川国貞 |

|

Subject: Jigoku Dayū 地獄太夫 |

|

Actor: Bandō Hikosaburō V 五世坂東彦三郎 |

|

Role: The Courtesan from Hell 遊君地獄太夫 |

|

Date: 1865, 3rd Month |

|

Bunkyū 4 文久4 |

|

Publisher: Iseya Kanekichi 版元: 伊勢屋兼吉 |

|

Size: 13 3/4" x 9 1/4" |

|

There is another copy of this print in the collection of Waseda University. |

|

SOLD! THANKS! |

|

|

|

JIGOKU DAYŪ THE HELL COURTESAN 地獄太夫 |

|

There is a story about the fifteenth century Zen monk Ikkyū (一休) who wandered about posing puzzling questions to anyone who would listen. The questions which probably were completely unanswerable were meant to edify and to lead eventually to Buddhist enlightenment. Nearly two hundred years after Ikkyū died an apocryphal tale claimined that the monk had encountered a famous courtesan who referred to herself as Jigoku Dayū. The two traded poems. In time the legend was expanded and took on a life of its own. By the nineteenth century it held a particular fascination.

In 1809 Santō Kyōden (山東京伝) published Honchō sui bodai zenden which dealt with this encounter between what ordinarily would be viewed as the sacred and profane. Kyōden's work inspired a number of later fine artists including Kuniyoshi, Kunisada II, Kunichika and Yoshitoshi. (1) It is not surprising that Kyōden would treat such a subject because that was the genre which dominated his works. (2) Mokuami (黙阿弥), who was one of the most prolific and popular playwrights of the mid-nineteenth century, wrote Jigoku Ikkyū-banashi which debuted on New Year's 1865. (3) |

|

***** |

|

"Let me tell you something, let me tell you something. A lot of those that you see in the stories is not true, but at the same time, I have to tell you that I always say, that wherever there is smoke, there is fire. That is true."

Quote from Arnold Schwarzenegger (アノルド シュワルツェネッガ) while running for governor on October 2, 2003.

Ikkyū (1394-1481) actually lived, but I can't be so sure about that particular courtesan. However, the stories that developed around his encounters with Jigoku Dayū make a lot of sense historically.

Ikkyū claimed to be the son of an emperor of Japan. This may or may not be true. What we do know is that he was never an imperial prince. Donald Keene acknowledges this, but adds: "...there is evidence in Ikkyū's poetry that he believed himself to be of imperial stock, and he often visited the palace to see the emperor." (4)

At the age of five his mother sent him to a temple to study to be a priest. Over the years he became well known for his keen mind, devotion and piety. Various stories are told of his unconventional nature and how that won him fame. Like Siddhartha in Hermann Hesse's novel Ikkyū spent years of religious adherence and abstinence only to give that up for the pleasures of the flesh. Not only did he seek out women, but boys too. (5) One of his more famous poems, The Brothel, describes the embraces of an elderly Zen priest and a prostitute. His peers expressed shock and abhorrence at his behavior., but he countered by charging them with hypocrisy. His counterclaim is more believable. (6) |

|

1. Demon of Painting: The Art of Kawanabe Kyōsai, by Timothy Clark, British Museum Press, 1993, p. 100. 2. In World Within Walls: Japanese Literature of the Pre-Modern Era 1600-1867 by Donald Keene the author gives a thorough description of Kyōden's work. On page 407 Keene describes an early collection of short stories describing forty-eight different ways of procuring a courtesan. One sincere male guest describes his enormous financial debt because of his love for this one woman. When she blames herself he tells her that he would rather wear rags than be without her. Awwwwwwwwwwwwwwwww, ain't that sweet. 3. Clark, p. 101. 4. Some Japanese Portraits, by Donald Keene, Kodansha International Ltd., 1983, p. 19. 5. Ibid., p. 23. 6. Ibid., pp. 22-3. Ikkyū excoriated many of his peers, but saved the best for his description of Yōsō, the twenty-sixth abbot of the Daitoku-ji. Keene tells us that he referred to him as "...a poisonous snake, a seducer and a leper." Don't hold back Ikkyū. Tell us what you really think. He also parallels the railings of Martin Luther who criticized the papacy for its selling of indulgences. Important Zen religious figures extorted money out of patrons with the promise of salvation. |

| CROSSING OVER |

|

|

The Greeks believed that when a person died the boatman Charon would ferry the soul of the deceased across the river Acheron to Hades.(1) In Japan Charon's near counterpart was Datsueba (奪衣婆), the Old Hag of Hell, seen above. (2) While the Old Hag does not ferry the souls to Hell she does sit by the river which flows into it, i.e. Sanzu no kawa(三途の川), and strips the damned of their robes which she hangs on a tree before their descent into the depths. |

|

|

|

(1)There was one proviso before Charon could transport a soul across the river. Upon death and proper burial or cremation a coin called an obol was placed under the tongue. When the soul reached the riverbank the coin acted as payment to the ferryman for the crossing. No coin, no transportation! --- at least not yet. Souls who failed to pay had to wander the shoreline for what some sources say was one hundred years before the crossing could be made.

Although I seriously doubt that there is any connection this is not totally dissimilar to ancient Chinese practice of placing a jade cicada in every orifice of a corpse. The Chinese believed that the cicada would die only to be reborn years later and these jade pieces would aid the soul of the deceased in their re-birth or resurrection in the afterworld. |

|

"O, be thou my Charon, And give me swift transportance to those fields Where I may wallow in the lily-beds.." Troilus to Pandarus, Act III, Scene II of "Troilus and Cressida" by William Shakespeare. |

|

Edna St. Vincent Millay, that ever upbeat

poetess, also wrote about Charon

in her "Sappho Crosses the Dark River into Hades." |

|

There are a number of versions of a famous painting by Arnold Böcklin, a late nineteenth century Swiss artist. Most people know this painting by the title "The Isle of the Dead." It portrays a picture of an oarsman, presumably Charon, delivering a totally swathed, mysterious standing figure seen from the back to an equally mysterious island. I am not a Böcklin scholar and have no idea what the artist intended, but what I do know is that the this is not Böcklin's title for the painting, but rather one chosen for it by an art dealer sometime later. The name stuck. |

|

|

|

One other thought: when we are children we can ask one of our parents "What is that?" It could be about almost anything and unless the parent doesn't know the answer the child becomes just that much more informed. As we grow older, if we are still curious enough, we can look things up for ourselves --- that is, if the information is out there and is readily available. That is the major problem: so much remains unanswered. I do not know much about Datsue-ba, but would like to know more. If anyone can assist me it will be greatly appreciated. |

|

The information on Datsueba comes from a great catalogue, The Demon of Painting: The Art of Kawanabe Kyōsai by Timothy Clark, pages 87-9. People who are interested in Japanese culture do not have to be interested in Kyōsai to want to own this book. This book is a font of information. I recommend it highly. (2) While researching Datsueba I found that there were two alternate readings of the kanji for her name: 奪衣婆 or 脱衣婆. Furthermore, I ran across the fact that 脱衣 means "to undress" or "taking off of one's clothes" and that a "dressing room" or "bathhouse" is a 脱衣所. All of these are certainly appropriate relationships linguistically to role played by the Hag of Hell. |

|

Fresh information on Datsueba |

|

| Detail shown above of an enshrined image of Datsueba by Kuniyoshi. |

|

On July 31, 2004 we asked our Internet visitors if anyone out there could provide more information about Datsueba. That day A.K., a frequent correspondent and contributor to this site, wrote to tell us of a web page posted by the Institute of Medieval Japanese Studies at Columbia University which summarized recent research on this figure. The main points stated that 1) Datsueba is first mentioned in a spurious Chinese sutra which deals with Bodhisattva Jizō and the Ten Kings of Hell. Along with a elderly, demonic male companion she punishes a thief, ties his head to his feet, strips him of his clothes and send him off to his final judgement. 2) In a 13th century work she skins the sinner if they arrive without clothes. 3) The Old Hag may also function as a goddess: At birth she may provide the newborn with their skin which she will remove at their death. |

|

Datsueba and her connection with the Blood Pool Hell chi no ike jigoku 血の池地獄 |

|

|

|

According to some sources there was a special torment reserved for certain women called the Blood Pool Hell. It is closely related to a belief systems dealing with pregnancies - both successful and failed. Here Datsueba played a different role and evolved into "a guarantor of safe childbirth." At birth she provides each child with a "placental cloth" which must be returned at the time of death.

WARNING! For those who are easily made queasy, disturbed or are just plain prudish: Do not read the entry shown immediately below.

The most blatant case of Buddhism's relentless enforcement of the blood taboo is the propagation of the Sūtra of the Blood Bowl (...Jap. Ketsubongyō [けつぼんぎょう]). The short apocryphal scripture of Chinese origins opens with the arhat Mulian... descending to hell in search of his mother. Upon discovering a blood pond full of drowning women, Mulian asks the hell warden why there is no man in this pond, and is told that this hell is reserved for women who have defiled the gods with their blood. Having found his mother, Mulian is unable to help her. In despair, he returns to the Buddha and asks him to save his mother. The Buddha then preaches the Sūtra of the Blood Bowl. This scripture first explains the cause of women's ordeals: women who died in labor fall into a blood pool formed by the age-long accumulation of female menses, and are forced to drink that blood. This gruesome punishment is due to the fact that the blood was spilled at the time of parturition contaminated the ground and provoked the wrath of the earth god."

Quoted from: The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender, by Bernard Faure, published by Princeton University Press, 2003, p. 73.

Mulian in Japanese is Mokuren (目連). In the Chinese version of the story of his mother she is a terrible woman who is not only greedy, but refuses to offer food to monks. And these are only two of her sins. In the Japanese version, the Mokuren no sōshi, she has morphed into a model mother. (Ibid., p. 146) "Yet, she is reborn as a hungry ghost as a punishment for her obsessive maternal pride. The 'sin of motherhood,' based on blind love of a parent for a child, is expressed by the topos of the 'darkness of heart' (kokoro no yami) of the mother." (Ibid., p. 146-7) Kokoro no yami = 心の闇.

There is another story of a living woman descending to the Blood Pool to rescue her mother. Like Mulian she is willing to drink from the pool. Her willingness alone transforms the Blood Pond into the Lotus Pond and all of the suffering women are rescued. "In a version of the ritual inspired by this scripture, and still performed today in Taiwan, the children of a dead woman, at the time of the funeral, redeem their mother's sin by symbolically drinking the blood that was spilled during their childbirth.

The Blood Bowl Sūtra seems to have spread in Japan during the medieval period. The fact that the Japanese commentaries emphasized menstrual blood rather than parturition blood has led to the somewhat misleading translation of the scripture's title as 'Menstruation Sūtra.'" This becomes a sin damning all women. "Because they were born as women, their aspirations, to buddhahood are weak, and their jealousy and evil character are strong. These sins compounded become menstrual blood, which flows into two streams in each month, polluting not only the earth god, but all the other deities as well." (Ibid., p. 76)

Faure continues by giving examples of ghost possession which can cause a female to descend to hell, but he also gives remedies to correct this injustice. One sect would place the Sūtra of the Blood Bowl into a woman's coffin to help bring about her salvation. (Ibid., p. 77)

"The Blood Pond Hell also appears in a text related to Tateyama, a place believed to be the gate to the other world..." Women were not allowed to climb the mountain, but they were allowed to ritually change themselves into men. However, to be careful, they were still banned from making the pilgrimage. Instead they would acquire copies of the Sūtra of the Blood Bowl which they would then give to monks who would carry them to the top and throw them into "...an earthly replica of the Blood Lake." (Ibid., pp. 77-8)

Faure notes that Buddhism considers menses natural, but still give it a sexist twist by giving it a karmic meaning. Hence, females defile their world because of past transgressions. While it may be considered natural "At the same time that it reinforces female guilt, Buddhism claims to offer absolution. By its magic power, the Blood Bowl Sūtra allowed women to avoid the ritual pollution of menses and childbirth to come into the presence of the gods and buddhas." Now the sutra wasn't just used for funerary purposes, but also as talismans for the living. On one hand Buddhism seemed to be condemning blood pollution while on the other praising motherhood. This concept of Buddhist salvation "...is based on male superiority, exploiting female fears, more than on compassion." (Ibid. p. 78)

"The blatant injustice of the Blood Pond Hell was accepted by women as just another 'fact of life' (or rather, of death) - a woman's life of toil and trouble." (Ibid. p. 79) In another account a nun describes a woman's life of grief: The husband has total control. "After they are married she necessarily suffers the pain of childbirth, and cannot avoid the sin of offending the sun, moon, and stars with the flow of blood." By the time of the Heiki monogatari (平家物語) pregnancy and childbirth were described as "pure hell" and 90% of women were thought to die giving birth. This, of course, was an exaggeration. (Ibid., p. 80) In a text called 'The Path to Purification' a description of the child in the womb makes it sound as disgusting as disgusting can be. This is as far from being reborn on a lily pad in the Western Paradise as one can get. 90% would be a shocking figure if it were true, but odds are, while the numbers were great, it couldn't have been that high. Faure relates a couple of other possibilities for the death of the mother after a long and torturous pregnancy and birth: 1) In the case of Māya, Buddha's mother, who passed away one week after giving birth, she died to avoid sexual intercourse in the future. Obviously a willful death. Or, 2) she died heart-broken knowing that Buddha, her beloved son, would be leaving soon. There are even accounts that say that the mothers of all of the Bodhisattvas died for the same reason seven days after their deliveries. "the could not escape the grief of motherhood." Māya's sister adopted the new born child, but she became blind from weeping when he left home. Her sight was restored when he returned. (Ibid., pp. 148-9)

The exclusion of women from sacred sites in Japan due to blood pollution is referred to as nyonin kekkai (如人結界). We have noted elsewhere that women were prevented from making pilgrimage climbs up mountains. This made sense in the Japanese mind for both the traditional association of the mountains with kami and the Buddhist concepts of pollution. "The mountain and the temple are symbolically equivalent. Therefore, the most extreme purity was required in both the temple's inner sanctuary and on the sacred peak. This contrasts with the profane impurity that rules at the bottom of the mountain or outside the urban temple's gate." Faure does cite the belief expressed by Abe Yasurō (阿部泰郎) that if a woman does defile a Buddhist site it is miraculously purified anyway. (p. 238)

In the 2008 translation of the Tale of Heike by Watson and Shirane it states in footnote 8 on page 161: "According to Buddhist belief, a woman may not become (at least directly) a Brahma, an Indra, a devil king, a wheel-turning king, or a buddha. She is expected to submit to and obey her father in childhood, her husband in maturity, and her son in old age when she is widowed." |

| THE FINEST KABUKI SITE ON THE INTERNET! |

| http://www.kabuki21.com/index.htm |

|

For additional information about and images by various artists of BANDŌ HIKOSABURŌ V link to the web site below. |

| BANDŌ HIKOSABURŌ V |

HOME

HOME