Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画formerly Port Townsend, Washington now Kansas City, Missouri |

|

|

Ges thru Haji Index/Glossary |

|

|

|

The orange flowers will be

used to mark new additions

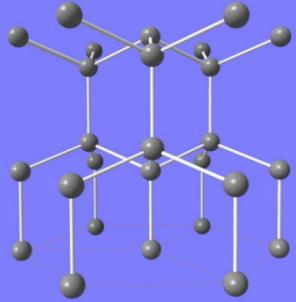

The molecular model on

Lonsdaleite was |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Gesaku, Geta, Gibōshi, Giga,

Gikakushi, Goko, Gōkyō jigoku, Gomazuri, Edmond de Goncourt, Gō no kagami, Gorōdayū Shonsui (or Shonzui), Goryō, Goshinbutsu, Goshoguruma, Gosu, Gozu, Gozu tennō, Gumbai, Gunjō, Guren jigoku and dai guren jigoku, Gyobutsu, Gyōyō, Ha, Habutae, Hachi dai-jigoku, Hachimaki, Hachiman, Hagatame, Hagoita, Hagoromo, Haiden, Haiku, Haimyō, Haji

戯作, 下駄, 擬宝珠, 戯画, 擬革紙, 胡粉, 五海道, 五鈷杵, 叫喚地獄, 業の鏡, 五郎太夫.祥瑞, 御霊, 護身仏?, 御所車, 呉須, 牛頭, 牛頭天王, 軍配, 群青, 紅蓮地獄 and 大紅蓮地獄, 御物, 杏葉, 派, 羽二重, 羽衣, 八大地獄, 鉢巻, 八幡, 歯固め, 羽子板, 拝殿, 俳句, 俳名, 黄櫨 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Gesaku |

戯作 ぎさく |

"The generic term for all popular fiction written between the middle of the 18th century and the close of the Edo period (1600-1868), and for literature of the early part of the Meiji period (1868-1912) that continued this tradition. The term originally meant 'written for fun'..." Generally flippant, facetious, but written with an 'elaborate structure'.

Quoted from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 3, p. 28, entry by Wolfgang Schamoni. 1 |

|

Geta |

下駄

げた |

Wooden clogs usually made of paulownia or cryptomeria wood with oak or magnolia teeth, i.e., ha (歯), supports. The term geta became popular during the Edo period although this type of footwear was being made as long ago as 300 B.C. During the Heian and Muromachi eras they were known by other names. The thong which holds the foot to the clog was generally made of cloth or leather.

Source: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 3, p. 30, entry by Miyamoto Mizuo. |

|

"Geta for men are plain wood and usually have black thongs while those for women are both lacquered and plain, and have beautifully colored thongs of silk or velvet."

Quoted from: Dictionary of Japanese Culture by Setsuko Kojima and Gene A. Crane, p. 76.

Mock Joya refers to the thong or strap as a hanao (鼻緒). Lacquer geta are referred to as nurigeta (塗り下駄). Tall geta are called mountain, yama, or travel, dochu, geta.

"As everything became luxurious in the Tokugawa days, geta also showed luxurious trends. During the Bunka-Bunsei era (1804-30) geta with little drawers to hold scent bags or tiny bells appeared. Such geta were used by fashionable women. Many women also discarded their geta after a few days, as they liked to always wear new geta." [This is what I call the Prada and Imelda effects.]

Quote from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 14.

Mock Joya also notes three other customs associated with geta: 1) They are often given as gifts to people on their sick beds in hopes this will help them get up and walk away; 2) Don't ever give them to someone you love because they might just use them to walk away and find someone else; And 3) Put moxa under the geta of a guest who just doesn't get the hint that they have overstayed their welcome. Light the moxa and the guest will leave.

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Eizan showing an elegant woman walking through the snow. She is wearing high, black lacquer getas. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

擬人化 ぎじんか |

Anthropomorphism |

|

Gibōshi |

擬宝珠

ぎぼうし

|

The jewel-like decoration found atop the newel post on a bridge, railing, platform or portable shrine. On the shrine it is called a souka (葱花 ).

Above is a photo taken by Fg2 and donated to the public domain through publication at http://commons.wikimedia.org/. In the right foreground is a large image of a gibōshi on a bridge leading to Matsumoto Castle.

The image to the left below was posted on commons.wikimedia.org and is also by Fg2, like the one posted above. It was too good to ignore.

First we want you to know that this 'jewel' always reminded us of a lotus bud about to flower. However, here it is: the following passage is from a footnote in W. G. Aston's Nihongi: Chronicle of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697. "Hirata conjectures that the jewel-spear (nu-boko or tama-boko) of heaven was in form like a wo-bashira.) Wo-bashira means literally male pillar. This word is usually applied to the end-posts or pillars of a railing or balustrade, no doubt on account of the shape on the top, which ends in a sort of a ball (nu or tama), supposed to resemble the glans. That by wo-bashira means a phallus is clear from his quoting as its equivalent the Chinese expression 玉莖, i.e. jewel-stalk, an ornate word for the penis." Others translate 玉莖 as the Jade Stem. |

|

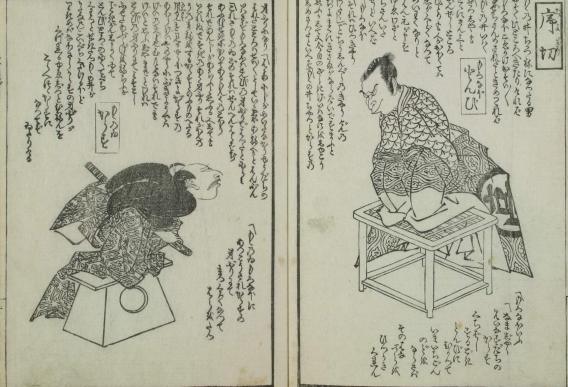

Giga |

戯画 ぎが |

Caricature, cartoon, comics - " "Giga" means pictures drawn in jest-that is, pictures showing entertaining comical stories, like cartoons. The word is also used to refer to pictures drawn just for entertainment." Quoted from: A Kabuki Reader: History and Performance: History and Performance by Samuel L. Leiter, p. 187.

Above is an ehon illustration by Toyokuni I from 1810. It is from the Zashikigei Chūshingura in the collection of Waseda University. |

|

Gikakushi |

擬革紙

ぎかくし |

Imitation leather made of paper - We have read that there were Buddhist strictures that prohibited the wearing or owning of leather goods, so this kind of faux leather was invented as one way of getting around this. In the Muslim world there were prohibitions banning the eating off of gold or silver plates. As a result their ceramicists created luster ware that gave the appearance of gold and/or silver without actually being either. The same principle may apply here.

The image to the left is of a tobacco pouch made of paper, but meant to look like leather. |

|

Gofun |

胡粉

ごふん

|

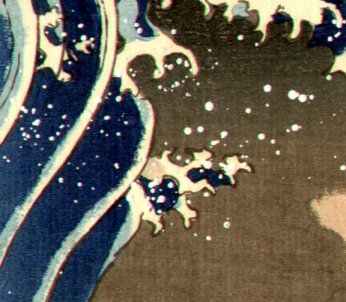

Literally "foreign powder": "...probably introduced from China. This white is made from ground calcined clam/oyster shells and can be mixed with colours using nikawa rather than nori to give opacity and thickness."

Quote from: Japanese Woodblock Printing, by Rebecca Salter, University of Hawai'i Press, 2001, p. 30

Nikawa is animal glue used as a binder. Nori is rice paste.

Unlike the rest of the printing technique the gofun is splattered onto the surface in a controlled manner. Generally it is found in snow scenes, but as you can see it is not strictly limited to that motif. Because it is splattered no two prints would be exactly the same. Nor would all examples of this print by Kuniyoshi necessarily have gofun applied after the traditional printing process is completed.

The images to the left are by Kuniyoshi. The top one shows a close up detail of the spume produced by the towering waves on the left.

The gofun illustrations were sent to us by our great contributor E. Thanks E!

beach in England. It was posted at Wikimedia Commons by S. Hinakawa.

|

|

|

||

|

|

||

|

Gokaidō |

五海道 ごかいどう |

The five great roads established during the Edo period (1603-1868) to link the provinces to the shogunal center which is now called Tokyo. The five were the Tokaidō connecting Edo with Kyōto along a coastal road, the Nakasendō which traveled to Kyōto through the mountains, the Nikkōkaidō, the Kōshukaidō and the Ohshūkaidō. |

|

Goko |

五鈷杵 ごこ |

A five-pronged vajra. See also our entry on kongōsho. |

|

Gōkyō jigoku |

叫喚地獄 ごうきょうじごく |

The Hell of Screams - the fourth of the Eight Great Hells: "Murderers, robbers, immoral people, heavy drinkers, those who sold saké mixed with water, and liars are destined to the Hell of Wailing (kyōkan jigoku 叫喚地獄)and to that of Great Wailing (daikyōkan jigoku), where they are terrified by the shouts of monstrous fiends mixed with the laments of sinners. The liars cannot even scream since their mouths and tongues are stuck together with iron needles, as a consequence of their past sins." Quoted from: "The Development of Mappo Thought in Japan" by Michele Marra in the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 1988, p. 43. |

|

Gomazuri |

ごま摺り |

In discussion of the special

technique of goma-zuri (ごま摺り) Hiroshi Yoshida notes in his Japanese

Woodblock Printing from 1939 that "Goma means sesame [胡麻] and suggests

black particles on white. It is obtained by a soft rubbing of the baren.

This is better produced while the surface of the paper is yet fresh. In

getting the goma effect, paste is not absolutely necessary, though it may be

needed to prevent the paper from slipping. A baren made of a four-strand

cord, or a worn-out baren, or a paper-cord baren - the weakest kind of a

baren - is the best for this purpose. An extravagant use of pigment is

required to produce a certain goma effect, and a scanty use of it produces

another effect. Use according to the need. Do not place too much pressure on

the baren." (p. 111)

"Gomazauri gets its name because it looks as if sesame seed has been sprinkled on the print. It is basically what happens when betazuri [falt color] does not print properly. The other name for this technique is kozozuri, from the Japanese word for 'youngster', because originally this effect was produced inadvertently by the apprentice printer trying to print flat colour. It is now seen as a technique in its own right, but is not easy to keep consistent across an entire edition. It happens more easily on rougher wood. In gomazuri, no nori is used on the block so the pigment particles remain suspended in the water and when printed appear as tiny spots. ¶ The fineness of the speckles depends on two further factors: the pressure of the baren and the dampness of the paper. Heavy baren pressure gives a finer texture than very soft baren pressure. The softest effect of all is achieved by just letting the paper rest on the block and absorb the colour. Damp paper gives softer definition to the spots than drier paper. Likewise, weakly sized paper will give a softer effect. Kōzo papers are particularly suitable. ¶ To print gomazuri apply a small amount of fairly watery colour (no nori) to the block and mix well with a damp brush. Print one or more times to achieve the desired effect. Gomazauri is best printed as the first impression on unprinted paper, other colours being added afterwards." Quoted from: Japanese Woodblock Printing by Rebecca Salter, pp. 108-109. |

|

"The shinsaku hanga from Watanabe's first decade in business were an initial step: his ambition was to seek out artists who could create pieces that corresponded to his vision of a revitalised woodblock print tradition, but not, in his words, artists constrained by traditional models or representing an attempt to 'emulate hand-drawn brushstrokes'. "Somewhat paradoxically, he found inspiration in the work of the Austrian painter and printmaker Fritz (Friedrich) Capelari(cat. 85-86), who had been stranded in Japan due to the outbreak ofthe First World War. In 1915, Capelari met Watanabe, who gave him reproductions of ukiyo-e masters and asked him to design original works derived from Japanese themes. The results pleased Watanabe and he instructed his printers to employ 'dry printing' techniques on thick hosho paper. In 'dry printing' (gomazuri, literally 'sesame seed printing') the proportion of water in the pigment is reduced, with the result that the printed surface becomes lightly speckled…” Quoted from: 'Waves of Renewal, Modern Japanese Prints 1900-60: Selections from the Nihon no Hanga Collection, Amsterdam'. |

||

|

Gō no kagami |

業の鏡 ごうのかがみ |

Karmic mirror (See also jōhari no kagami) |

|

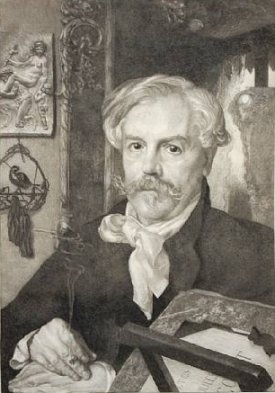

Goncourt, Edmond de |

ゴンクール. エドムンド |

Edmond (1822-96) along with his brother Jules (1830-70: ジュール) were among the first true enthusiasts for 'things Japanese'. They were early advocates for Japanese woodblock prints which had their first, official, government sanctioned debut in Paris in 1867. ¶ In 1891 Edmond published a book on Utamaro followed in 1895 with one on Hokusai. What these volumes lacked in factuality they made up for in enthusiasm and eloquence.

Edmond and Jules were inseparable. They wrote their novels together, gossiped maliciously together and debauched together. They shared all things good and bad. There was no negligible difference in their collective passion for an 'idealized' Japan based on their perceptions of the arts which they had seen in exhibitions and in the shops of a several brave dealers. To them Japan was a land of light - glorious light as expressed in the colors of their prints. ¶ While they considered themselves great literary stylists their novels never reached the popularity of several of their more famous peers like Flaubert and Zola. The Goncourts rejected romanticism for naturalism - even somewhat lurid naturalism. Van Gogh was believed to have read several of their works. Chérie is believed to be the impetus for Van Gogh's interest in Japanese prints. In Manette Salomon the Goncourts describe a fictitious Parisian artist depressed by the long, drab, gray days of winter. In an effort to escaped his malaise he opens an album of Japanese prints and is able to escape his dismal world by dreaming about a sun filled and exotic land. Later, "...in Maison d'un artist, Edmond de Goncourt recollects his collaboration with his brother Jules on Manette Salomon and theri interest in Japanaiserie: 'It is there that you will find those books of sunny prints in which, on the gray days of our dreary winter, with its cold, grimy skies, we made Coriolis [the hero artist] (ourselves in fact) seek some of the agreeable light of the empire of the RISING SUN'."

Source: An essay by Tsukasa Kōdera, "Van Gogh's Utopian Japonisme," at the beginning of the Catalogue of the Van Gogh Museum's Collection of Japanese Prints.

It is interesting that in the literary world they were known as realists and not romantics yet that didn't stop them from romanticizing an idealized Japan. It was this Japan which had such a profound effect on Van Gogh and is one of the main reasons he moved to the south of France. If he couldn't travel to Japan at least he could try to capture the light of the Midi as the next best thing.

The image to the left is from a print of Edmond by Felix Bracquemond. |

|

Gorōdayū Shonsui (or Shonzui) |

五郎太夫.祥瑞 ごろうだゆう.しょんずい |

"The introduction of real porcelain-making into Japan is attributed to Gorodayu Shonsui, who went to China to study the art, and returned to his own country in the year 1513. After his return he settled in Hizen, and succeeded in making a ceramic ware decorated in the Chinese fashion with cobalt under the glaze, although authorities differ as to the kaolinic structure of the material. A specimen of porcelain said to have been made by him in China and marked, with his name as inscribed below, is preserved in Japan at Nara." Quoted from: Oriental Ceramic Art: Collection of W. T. Walters, 1899, p. 736.

See our entry on sometsuke and gosu, found below. |

|

"It was a potter of the name of Gorodayu Shonsui who brought from China, about 1520, the elements of the making of porcelain. The village which rose up round his first kiln took the name of Arita. There is every reason to suppose that the pieces that came from the hand of Shonsui were timid copies of Chinese porcelain, probably of small dimensions and and of blue and white. His two pupils, Gorohichi and Gorohachi, were already more skillful." (Ibid., p. 712)

In Arts and Decoration, vol. 5, issue 10, 1915 (p. 392) it says: "About the beginning of the 16th century a prominent Japanese potter named Gorodayu Shonzui went to China to learn the secrets of the kilns at Foo-chow. There he learnend how to mix the paste and also to decorate with blue under the glaze. He was then able to make a fairly good imitation of the blue and white ware of the Ming dynasty. There is little doubt, however, that the actual beginning not only of the porcelain, but of all decorated pottery in Japan, was the immediate result of the invasion of Korea at the end of the 16th century, and indeed the Japanese acknowledge their indebtedness to Korean immigrant potters for the origin of the porcelain of Hizen and the decorated faience of Satsuma..."

"In the sixteenth century Gorodayu Shonzui visited China and learned the art of making porcelain, and on his return to Japan brought a quantity of the clay with him. On the supply being exhausted, however, the manufacture stopped. ¶ After Hideyoshi's invasion of Korea, towards the end of the century, many captives were brought back, including a Korean potter, Risampei, who discovered on the hills of Hizen a clay suitable for the making of porcelain. Kilns were erected, and the new manufacture started in earnest." Quoted from: Arts and Crafts of Old Japan by Stewart Dick, 1909, p. 103. |

||

|

|

||

|

Goryō |

御霊 ごりょう |

Spirits of the dead, often described as angry. Ghosts! "In the tenth century, more miyadera [mixed Buddhist/Shinto sites] appeared in the capital as sites for a new type of ritual practice; the pacification of so-called goryō or 'angry ghosts.' Here, again, it must be noted that these ghosts were neither traditional kami, nor part of the Buddhist pantheon... Goryō were the ghosts of aristocrats who had been falsely accused of some political crime and had died in disgrace, often in exile. Their spirits were believed to have returned to the capital, where they not only haunted their enemies, but also caused epidemic that struck the entire population. Goryō festivals started as a popular practice in the early ninth century.... These festivals, called goryōe, also included a wide range of entertainments (songs, dances, wrestling, horse races, archery and popular theatre), and attracted large crowds. Understandably, the Court felt ill at ease with this popular worship of those ghosts of its dead enemies, and tried to suppress or at least control goryōe. One way to achieve this was by staging official goryōe, while prohibiting 'private' goryōe." After an extended epidemic which took many lives the Court held a goryōe on its own grounds in 863. "Altars to six noted goryō were erected, monks chanted... musicians played court music, sons of the prominent courtiers, as well as Chinese and Koreans... performed dances, and various 'miscellaneous entertainments' were staged. The gates of the palace were opened, and commoners flocked to the grounds to enjoy the display. Two years later, in 865, private goryōe were banned, but with little effect." (Source and quote from: Buddhas and Kami in Japan: Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm, p. 26-7)

Goryōe were performed in graveyards, temples and miyadera. By ca. 950 special buildings, Goryōdō, had been erected on holy ground to hold these events. One of the most important of these was at the Kitano Tenmangū devoted mainly to the spirit of Sugawara Michizane.

See also our entry on Tenjin, the deified name of Sugawar Michizane, on our Tengu thru Tombo page. See also our entry on onryō a different type of vengeful spirit on our O thru Ri page. |

|

Goshinbutsu |

護身仏?

ごしんぶつ |

A small round amulet, pocket-sized, with an image of a Buddha or other similar efficacious figure.

The image to the left is from the British Museum collection. It dates from the Edo period. |

|

Goshoguruma |

御所車

ごしょぐるま |

An ox-drawn cart used by the early court nobility. The image to the left is a detail from a print by Hokusai.

According to Royall Tyler a 14th c. commentary relates the story that the Empress asked Lady Murasaki to write some new tales to amuse the court. "Having none to offer, the empress asked Murasaki Shikibu to write one. The lady therefore went on pilgrimage to Ishiyama-dera, a temple near the southern end of Lake Biwa, a day's journey by ox carriage east of Kyōto, in search of inspiration." This may have been the origin of The Tale of Genji.

Quoted from: "Harvard Magazine", May-June 2002, Vol. 104, No. 5, p. 32.

John K. Nelson in his Enduring Identities refers to this vehicle as an iidashi-guruma, or more informally, a gissha. |

|

Gosu |

呉須 ごす |

"The best blue-and-white wares were painted with the manganiferous-cobalt ore imported from China, called by the Japanese gosu, and as this ore was carefully refined the blue colour is often of fine quality, though in the most careful painting it looks paler and lighter than the Chinese pigment." Quoted from: Porcelain: A Sketch of its Nature, Art and Manufacture by William Burton, 1906, p. 143.

In Outlines of the Geology of Japan... from 1902 gosu is described as "impure earthy cobalt".

See also our entry on sometsuke. |

|

"The earliest Seto porcelain was decorated with under-glaze blue, the native Japanese cobalt (ji-egu) being used till 1830, when it was superseded by the richer Chinese gosu." Quoted from: Porcelain, oriental, continental and British... by Robert Lockhart Hobson, 1906, p. 104.

"The Japanese under-glaze blue in the older porcelains was made from the cobaltiferous ore of manganese imported from China, and the fine quality of this imported blue, which the Japanese call gosu, forms a useful criterion of the age of the piece ; the more modern ware being usually decorated with a cheaper smalt sent out from Europe, which has a thin, garish and altogether inferior tint." (Ibid., p. 75)

"In Japan, underglaze painting on porcelain means cobalt brushwork (sometsuke) or painting with natural gosu, a 5-percent cobalt mineral with iron, aluminum, and manganese components. To prevent the color from running, a suspension of concentrated green tea is used. A somewhat indistinct purple or grayish shade of blue is produced by firing in reduction. Using an industrially produced mixture of pure cobalt, manganese, iron oxide, and nickel fritted at about 2192°F (1200°C) creates a brighter blue." Quoted from: Modern Japanese Ceramics: Pathways of Innovation & Tradition by Anneliese and Wulf Crueger and Saeko Ito, 2007, p. 29.

In Potters of Japan: Another Look at the Timeless Art of Nine Families by Bill Geisenger from 2010 the author discusses the preparation and application of gosu on works by members of the Kondo family (p. 27): "Gosu is the blue pigmentused in sometsuke. As used by the Kondo family, it is a natural material containing various mineral elements, with cobalt being the dominant colorant. Such natural blends of cobalt, producing various qualities of blues, has been key in the history of porcelain decoration from Japan to Persia. The gosu is prepared by grinding in a mortar for days until very fine. To improve its character for for brush application, it is mixed with green tea. It may be applied to greenware, but generally work is bisque fired first prior to the gosu application. A clear glaze is then sprayed on the surface. ¶ After firing, the gosu can be many shades of blue depending on the concentration in the tea, thus giving depth to the images painted by these master artists: but before firing, the difference between concentrations is nearly imperceptible. Naturally occurring gosu with the right balance of elements to give the particular tone of blue desired by the Kondo family is not available anymore..."

On p. 29 Geisinger adds: "Firing of the kiln is critical to have the gosu turn its unique shade of blue." |

||

|

Gozu |

牛頭 ごず |

Ox-headed demon or deity often found in images of the Buddhist hell.

"...Gozu's task was to torment those who during their lifetime had eaten beef (a breach of Buddhist dietary laws)..." |

|

Gozu tennō |

牛頭天王 ごずてんのう |

Said to be the Indian god Gavagriva.

"The main deity enshrined here was (at least by the mid-eleventh century) Gozu Tennō or 'the Bull-Headed Heavenly King,' a deity of unknown origin who was later identified further with the more orthodox Buddhist divinities Yakushi and Jūichimen Kannon on the one hand, and the kami Susanoo on the other. In a variety of sources,it is suggested that Gozu Tennō was a foreign deity of Indian or Korean origin. Whatever his origin, this foreign deity was believed to possess extraordinary magical powers, and to be supremely effective in dispelling and destroying disease-spreading goryō." Quoted from: Buddhas and Kami in Japan: Honji Suijaku as a Combinatory Paradigm, introduction by Mark Teeuwen and Fabio Rambelli, p. 27.

"...the transformation of vengeful spirits into protectors can be seen in Gozu Tennō who protects people against smallpox, dōsojin road deities who protect travelers, and Kitano Tenjin for everything related to water, fire, and thunder." Ibid., entry by Irene H. Lin, p. 70 |

|

Gumbai (or gunbai) |

軍配

ぐんばい |

War paddle

We found the image to the left at Pinterest. |

|

I have to admit to a bit of confusion on this one. In our entry on tōuchiwa we list it as a fan which has its origin in the T'ang Dynasty (618-907) from China. But it looks remarkably like the gumbai and what the difference is is unknown to me. Dorothea Buckingham in her The Essential Guide to Sumo (p. 70) is absolutely convinced of the distinction between the two. "The wooden fan held by the referee is not a fan at all, but a war paddle. Legend has it that Nobunaga [1534-82 - 信長] ...was an avid sumo fan and designed the gunbai for the sumo referee. The gunbai was later used by the warring commanders as a battle signal." Turning the gumbai signaled the beginning of a battle. Buckingham notes that some experts believe it was a war paddle long before it was used in sumo.

The rank of the referee (gyōji: 行司) is indicated by the color of the braided cord (himo: 紐) hanging from the gumbai. The highest rank uses a purple cord and the next highest a purple and white one. Lower ranks use scarlet followed by scarlet and white, then green and white followed by green or black. "The gunbai of the senior gyoji are often trimmed in silver. Some are decorated with gold leaf designs or kanji characters; others are lacquered."

紐 or himo, which is the braided cord hanging from the gumbai, can also be read as gigolo or pimp. I have no idea why. This seems rather odd, don't you agree? If you know why this is please write and tell me. (No opinions please. Just the facts maam or sir as the case may be.) |

||

|

|

||

|

Gunjō |

群青

ぐんじょう

|

Ultramarine -

The Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary from the 1954 edition defines gunjō as "...ultramarine; sea blue; navy (=French) blue."

The image to the left on top is a piece of azurite found in Shilu Copper Mine, Guangdong Province, China. It was posted at Wikimedia Commons by Eric Hunt. The image below is from a commercial website, pigment.tokyo, which is an absolutely remarkable source on pigments. It shows the natural color gunjō when two coats have been laid down. We would encourage you to visit and explore this site. It is astounding. (We will remove the image if they request that we do so.) |

|

Guren jigoku and dai guren jigoku |

紅蓮地獄 ぐれんじごく and 大紅蓮地獄 だいぐれんじごく |

The Crimson and Great Crimson Lotus Hells: "...the seventh and eighth of the eight freezing hells. They are named after the splotchy red appearance of their inhabitants’ frostbitten skin, which is said to resemble the blossoms of a crimson lotus." Quoted from footnote 46 of R. Keller Kimbrough's translation of The Tale of the Fuji Cave.

These hells are reserved for thieves, burglars, bandits and pirates. The souls condemned to freeze in the ice there are to remain for 35.000 years. |

|

Gyobutsu |

御物 ぎょぶつ |

Imperial treasure(s) |

|

Gyōyō |

杏葉

ぎょうよう |

Apricot leaf - used as a family crest or mon.

"The puzzling 'tassel' design, written with ideographs that literally mean 'apricot leaf,' appears to be a pattern which originated in Southeast Asia and eventually came to Japan through T'ang China." This motif resembled the tassels attached to saddles and bridles. It is often confused with the zingiber motif.

Source: The Elements of Japanese Design: A Handbook of Family Crests, Heraldry and Symbolism, by John W. Dower, p. 126. |

|

Ha |

派 は |

Ha means clique, faction, school or sect. For example, Torii Kiyonaga (鳥居清長: 1752-1815) was the fourth head of the Torii school or Torii ha (鳥居派). |

|

Habutae |

羽二重

はぶたえ |

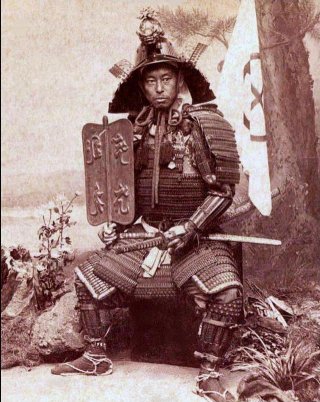

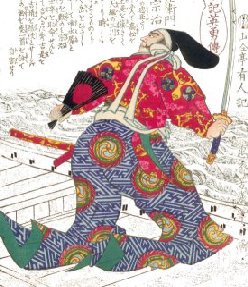

A type of silk that was worn by samurai. According to at least one web site there were government edicts which restricted its use at times only to this class of men. Peasants and women were forbidden to wear it.

The detail to the left shows a rōnin or masterless samurai wearing a habutae as a summer garment. Notice the crest or mon visible near the figures left shoulder blade. This fellow is taken from an early Kunisada print ca. 1816-17 portraying the actor Matsumoto Kōshirō V as Ono Sadakurō. |

|

Habutae |

羽二重 はぶたえ |

This new term is the same as the one above, but here it means something somewhat different. "Today actors cover their real hair with a tight cloth called a habutae." Quoted from: A Guide to the Japanese Stage: From Traditional to Cutting Edge by Cavaye, Griffith and Senda, p. 75. |

|

Hachi dai-jigoku |

八大地獄 はちだいじごく |

The Eight Great Buddhist Hells |

|

Hachimaki |

鉢巻

はちまき |

A headband: A thin towel or strip of cloth tied around the head. Originally imbued with a religious significance today they are also worn by laborers. They date from as early as the 4th century.

"Hachimaki came to be worn in battle, apparently because they were believed to strengthen the spirit. They were also believed to repel evil spirits; for this reason boys wore hachimaki made of iris leaves on Boy's Day...and sick people or women giving birth often donned them." (Quoted from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 3, entry by Miyamoto Mizuo, p. 74)

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Shunshō.

Hachimaki can also be written as 鉢巻き. Literally this term means 'to tie around a bowl'. "Many Japanese wear one when they apply themselves to an arduous task, to gather strength, both spiritually and physically. It also serves to absorb sweat. They wear one when carrying a portable shrine (mikoshi) at festivals, when selling items at street fairs, when doing construction work, or when studying for entrance examinations. Schoolchildren often wear red or white ones at athletic meets (undōkai) to distinguish teams." (Source and quote from: Dictionary of Japanese Culture by Setsuko Kojima and Gene A. Crane, pp. 86-7)

"Under the helmet and inner cap, finally, the bushi wore a band of cloth around his head tied either at the back... or in the front. This headband was called hachi-maki, and it was usually white in color, in deference to the ever-present possibility of death. Headbands in red (aka) were also used. These hachi-maki became extremely popular among Japanese fighters of all ages, classes and periods. During World War II, white hachi-maki were employed as the insignia of the suicide pilots, the kamikaze, who hurled themselves and their planes loaded with explosives against enemy vessels in a desperate attempt to reverse the tide of war. These headbands are still used today in many Japanese clubs where arts of combat and other competitive sports are taught and practiced." (Quoted from: Secrets of the Samurai: The Martial Arts of Feudal Japan by Oscar Ratti and Adele Westbrook, p. 217) |

|

"Whether a hat (kasa) is worn or no, the head is invariably wrapped with a hachimaki, a sort of small towel (tenugui) of white cotton. In warm weather this is tied as a band about the forehead and knotted in front (knotting it behind was the warrior's fashion) ; in winter it becomes a hōkaburi, covering the top of the head and tied beneath the chin. Women wear it turban-fashion, completely enveloping the hair." Quoted from: Victoria and Albert Publication 120T by Albert J. Koop, p. 18, 1920.

"The sweatbands used by mikoshi bearers and other matsuri teams are called hachimaki, created from a cotton towel or tengui, which can be twisted, folded, rolled, or knotted in many different ways. The style of wrapping can refer to a specific task or a particular figure in folklore, and it further distinguishes members of one group from other matsuri participants. Like the happi coat, wearing a hachimaki indicates intent to exert strenuous effort." Quoted from: The Cherry Blossom Festival: Sakura Celebration by Ann McClellan, p. 61. |

||

|

|

||

|

Hachiman |

八幡 はちまん |

God of War - Hachiman is "One of the most popular Japanese deities, traditionally regarded as the god of archery and war, in which context he is referred to as yumiya Hachiman..." He is worshipped at tens of thousands of shrines and sub-shrines. That amounts to about half of the registered shrines in Japan.

'Hachiman' literally means 8 flags.

Sometime between 765 and 781 Hachiman received the Buddhist title of Daibosatsu or great bodhisattva and was regarded as an incarnation of the Amida Buddha. The Minamoto adopted Hachiman as their clan deity. In time he was portrayed as both a warrior and a Buddhist priest. (Source and quotes: A Popular Dictionary of Shinto by Brian Bocking)

At Tobishima in Ugo province Hachiman devotees don't eat chicken because the god was believed to dislike them. Another group which worshipper a different god have a taboo against eating crabs. |

|

Hagatame |

歯固め

はがため |

Tooth hardening: "...the practice of chewing tough edibles - such as rice cakes, radishes, or certain varieties of meat and fish - during the New Year's season. Strong teeth, it was thought, ensured good health and longevity." (Quoted from: Quoted from: Jewels of Japanese Printmaking: Surimono of the Bunka-Bunsei Era 1804-30 by Joan Mirviss and John Carpenter - cat. entry #15, p. 62)

"Among the many New Year's customs was that of tooth-hardening. This was observed in the Palace on the second day of the year, when the Imperial Table Office prepared certain dishes, such as melon, radish, rice-cakes, and ayu [鮎] fish, which were supposed to strengthen the teeth. This in fact had the same purpose as many other New Year practices, viz. the promotion of health and longevity. Evidently the tooth-hardening foods were served on yuzuriha [譲葉] leaves. This strikes Shōnagon as strange since the same leaves were used to serve the food for the dead." (Quoted from: The Pillow Book of Sei Shonagon, translated and edited by Ivan Morris, Penguin Classics, 1979, footnote 124, p. 294)

The photo to the left is of yuzuriha leaves shown here courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. |

|

Hagi |

萩 はぎ |

Bush clover:

We chose the marubahagi (丸葉萩), Lespedeza cyrtobotrya image posted by Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. |

|

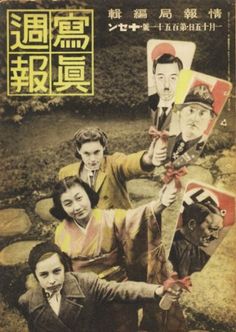

Hagoita |

羽子板

はごいた |

A battledore used in the game of hanetsuki.

"As New Year's approaches, hagoita...are displayed in all their glory in shops. Particularly women, young and old, crave for these hagoita. These beautiful battledores are, however, not to be used for playing the game of hane... It is the plainer ones that are used for thsi purpose." The game goes back to the Muromachi period (1392-1573). The shuttlecock was composed of several feathers stuck in a soapberry nut and the battledore was generally carved from paulownia, cryptomeria or other light wood.

Originally the battledores were simple, but in time some were spruced up by elaborate paintings. These were the ones used by members of the Imperial court. "Later on, Edo citizens with wealth and culture added so many artistic touches and such elegance to them that they became unsuitable in actually playing the game.... As Kabuki dramas were popular, there appeared in Edo hagoita bearing the likenesses of famous actors in their great roles, made with oshie or gorgeous silk and brocade pieces pasted together to represent persons and their costumes."

Sources and quotes from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese (p. 470-1)

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Tamikuni (多美国) showing the actor Sawamura Kunitaro II as an onnagata decorating a battledore.

In the section above Mock Joya puts the earliest date for the use of the hagoita back to the 14th c., but in 1984 The Shogun Age Exhibition gives a different chronology on page 259. "Documents of the time indicate that hanetsuki originated in the Heian period (12th century) as a kind of exorcism, and only in the Muromachi period (15th century) did it become a form of recreation."

But wait! The Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan (vol. 3, p. 77, entry by Yamada Tokubei) states "The first recorded mention of the game occurs in 1432, when it was played at the imperial court." This was published in 1983, one year before the Shogunal exhibition. Both cannot be correct.

Our policy is to post contradictory information whenever we feel that each source has some degree of credibility. Conflicts are way beyond our ability to resolve. That is for future generations of scholars. Perhaps our postings will help in this process. |

|

"The girls, dressed in their best robes and girdles, with their faces powdered and their lips painted, until they resemble the peculiar colors seen on a beetle's wings, and their hair arranged in the most attractive coiffure, are out upon the street, playing battledore and shuttlecock. They play not only in twos and threes, but also in circles. The shuttlecock is a small seed, often gilded, stuck round with feathers arranged like the petals of a flower. The battledore is a wooden bat; one side of which is of bare wood, while the other has the raised effigy of some popular actor, hero of romance, or singing-girl in the most ultra-Japanese style of beauty. The girls evidently highly appreciate this game, as it gives abundant opportunity to the display of personal beauty, figure, and dress. Those who fail in the game often have their faces marked with ink, or a circle drawn round their eyes. The boys sing a song that the wind may blow; the girls sing that it may be calm, so that their shuttlecocks may fly straight." Quoted from: The Mikado's Empire by William Elliot Griffis, 1896, p. 455.

A modern hagoita posted at Pinterest

"Two prominent features of the New Year's celebration are the many-formed and elaborate kites which are flown the first half of the first month by the boys, and the battledore and shuttlecock sets which are the pride of the girls. The battle boards, often of excellent workmanship, are made of fine kiri wood and padded on one side with bright silks into a raised portrait of a famous actor or hero in history. The shuttlecock is made of the seed of the soapberry (mukuroji) plumed with five feathers at one end. The penalty for letting the shuttlecock touch the ground is a black smudge on the face." Quoted from: Japanese Collections (Frank W. Gunsaulus Hall), published by the Field Museum of Natural History, 1922, p. 10.

"Their battledores are works of art." Quote from: The Heart of Japan: Glimpses of Life and Nature... by Clarence Ludlow Brownell, 1904, p. 77.

"It was customary under the old régime in Japan to compliment the parents of a new-born infant with a battledore and shuttlecock if it was a girl, with two bows and arrows if it was a boy." Quoted from: The Badminton Magazine of Sports and Pastimes, Volume 3, 1896, p. 433.

The print shown above is by Shibakuni, dated 1824. It comes from the collection of Mike Lyon. To see more of his collection go to http://woodblockprints.org/lyon_collection/index.php

During the economic reforms instituted by Matsudaira Sadanobu (1758-1826) one of the stipulations was that "In the making of toys, dolls and their paraphenalia, battledores and toy bows for commoners, the use of gold and silver leaf was forbidden." Quoted from: The Economic Aspects of Japan by Yosaburō Takekoshi, vol 3, p. 153.

"The game originated in China and was known in Japan as early as the Heian period. At first it was a pastime reserved for the nobility, and beautifully gilded and painted hagoita were presented by caprpenters and other tradesmen to their patrons at New Year.... That hagoita were decorated with auspicious symbols possibly led to their being made and sold at shrine and temple festivals as lucky charms and protections against fire and, of all odd things, mosquitoes! Playing initially served as an exorcism rite becoming a girl's game in the Muromachi period (1333-1568)." Quoted from: Playthings and Pastimes in Japanese Prints by Lea Baten, pp. 25-26.

"The earliest hagoita were flat, delicately painted and gilded on both sides. By the end of the Edo period, one side was flat and painted while the other side bore the flamboyant portraits of kabuki idols, their costumes made of silk and brocade of the oshi-e (padded picture) technique." (Ibid., p. 26)

While researching hagoita we found the image shown above posted at commons.wikimedia. Instead of actors decorating these paddles it shows Prime Minister Konoe, Mussolini and Hitler. Now there is a trio for you. |

||

|

|

||

|

Hagoromo |

羽衣

はごろも

|

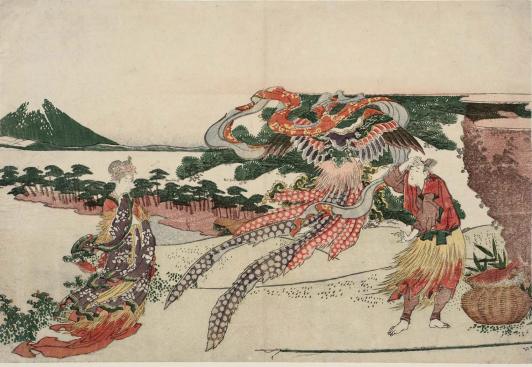

A heavenly feather robe - "The hagoromo legend, handed down in several versions, also extant in China, recounts how a Buddhist angel (tennin) ascends the mountains in order to admire the view of the Suruga landscape. On the branches of a pine tree, the angel had left her heavenly feather robe which is discovered by the fisherman Hakuryō who happens to pass by. The fisherman consents in returning the feather robe to the angel only under the condition that she should first perform for him a celestial dance. (Suruga no mai)." Quoted from: Irezumi by Willem R. van Gulik, p. 70.

Hokusai illustration to the Nō

play Hagoromo.

The image to the left is also from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and is by Hiroshige. Below is a Hokkei surimono from the collections at Harvard.

"In the Nō play Hagoromo, 'Feather Robe', by Zeami, an angel (tenjin) falls down to Matsubara on the Bay of Miho, and a fisherman takes her feather robe, which he finds hanging on a pine tree. She laments that she will be unable to fly back to Heaven without it, and eventually the fisherman yields to her entreaties, on condition that she dance for him. She performs a beautiful dance of joy, and ascends to heaven, bestowing gratitude and blessings." Quoted from: The Harunobu Decade: A Catalogue of Woodcuts by Suzuki Harunobu and his followers in the Museum of Fine Arts by David Waterhouse, text volume, p. 208. |

|

Haiden |

拝殿

はいでん |

In Shinto the "Hall of Worship. A shrine building or equivalent space, part of the hongū, which is available to worshippers for their prayers and offerings."

To the left is the Kanshinji haiden (観心寺.拝殿) posted at commons.wikimedia by Kenpei. |

|

Haiku |

俳句 はいく |

"The term haiku (俳句) was coined in the 1890s by Masaoka Shiki (1867-1902), a poet, author, and literary critic in Meiji Period Japan. He proposed to 'reform' the hokku (発句) by separating it completely from the verse sequences of which it previously was used as the opening verse. With time, hokku and haiku grew farther apart." Quoted from: 'Surprise comparisons in Kunisada's print series Mitate sanjūrokkusen' by Herwig, Vos and Griffith, Andon 96, footnote 2, p. 61. |

|

Haimyō (also haimei) |

俳名 はいみょう |

Poetry name. It can also be called a haigō 俳号. Andrew Gerstle in his Creating Celebrity: Poetry in Osaka Actor Surimono and Prints speculates that actors, who were considered among the lowest levels of Japanese society, were allowed "...to circumvent the class system and socialize through art circles. This was important for actors." |

|

Haji |

黄櫨

はじ |

Japanese sumac tree - the bark was used to make a yellow pigment, the berries are gathered for wax to be made into a higher quality of candles.

The image to the left is from CAMEO, a pigment site at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. |

|

LINKS TO OUR OTHER INDEX/GLOSSARY PAGES Click on any of the pages listed below!

|

||

|

|

The beautiful photo of wisteria being used as wallpaper is shown courtesy of Katorisi at http://commons.wikimedia.org/. |

|

HOME

HOME