|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

Kesa thru Kodansha |

|

|

|

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Kesa, Keshō, Ketsubon kyō, Keyaki, Roger Keyes, Kichō, Kihada, Kijo, Kikkō, Kiku, Kikusui mon, Kikyō, Kikugawa Eizan, Kimedashi, Kimekomi, Kinbaibai, Kinchaku, Kine, Kingyo, Kinmedai, Kinpaku, Kinuta, Kiri, Kirikane, Kiri seal, Kiseru, Kisha, Kitsune, Kitsunebi, Kitsune ken, Kiwame, Koban, Kochōsō, the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan

袈裟, 化粧, 血盆経, 欅, 几帳, 黄蘗 or 黄檗?, 鬼女, 亀甲, 菊, 菊水紋, 桔梗, 菊川英山, 極込, 禁売買, 巾着, 杵, 金魚, 金目鯛, 金箔, 砧, 雲母摺, 桐, 桐紋. 煙管, 騎射, 狐, 狐火, 狐拳, 極め, 小判, 胡蝶装, 講談社日本百科事典 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Kesa |

袈裟

けさ |

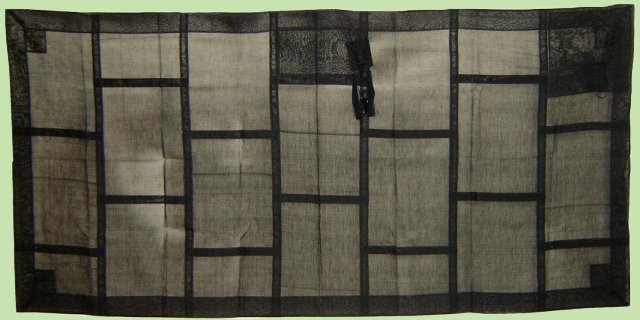

A Buddhist priest's or monk's robe. Traditionally made from a patchwork of scraps of inexpensive cloth modeled on a golden kesa made for Shakyamuni (just Shaka in Japanese 釈迦), the historical Buddha (ca. 563-483 BCE), by his mother. At the time of his death one of his disciples took the kesa to a mountain retreat to await the coming of Maitreya or the Buddha of the Future. [The Maitreya is called Miroku in Japanese (弥勒).]

These robes were made of donated pieces of cloth and frequently handed down from priest to priest as symbols of religious power and lineage. In time the robes became finer because better and better scraps were being donated.

Somewhat like a toga the kesa was worn "...diagonally covering the right shoulder and passing under the left armpit."

Quote from: Dictionary of Japanese Culture by Setsuko Kojima and Gene A. Crane, p. 166. |

|

These robes were often worn by komusō. (See that entry.) To the left is a detail from a Hiroshige print of two mendicant monks wearing kesa."

The kesa is sometimes described as a shawl or scarf. In The Art of Buddhism: An Introduction to Its History and Meaning Denise Leidy says: "The making of shawls is still considered a religious act. Such garments serve as a reminder of the teachings of Buddha, and some, which can pass from a master to a disciple, contain relics and presumably the wisdom and understanding of a deceased master. Other shawls were made from clothing, including theatrical costumes, donated to monasteries upon the death of a devotee in the hopes that the prayers associated with the making of clothing into a religious garment would also protect the soul of the deceased. ¶ A standard part of the monastic costume, shawls are commonly subdivided into horizontal and vertical registers as an illusion to the rags and other pieces of discarded clothing used by the Buddha and other early practitioners. Shawls with five such bands are used daily, while more elaborate pieces, which can be divided into up to twenty-five bands, are used by high-ranking monks during formal events.

"The kesa (kaśāya in Sanskrit)... is the oldest and most important Buddhist garment, and the prototype for other Buddhist textiles." (Quoted from: Flowers, Dragons and Pine Trees: Asian Textiles in the Collection of the Spencer Museum of Art by Mary Dusenberry, p. 256) Later the author notes "The monk Dōgen (1200-1253), a brilliant scholar and founder of the Sōtō sect of Zen Buddhism in Japan, wrote a treatise on the kesa in which he emphasized its crucial role in the practice of Buddhism. In his Kesa kudoku (The Merit of the kaśāya), Dōgen wrote that the garment 'is the very essence of those who have realized enlightenment.' Imbued with the spiritual power of a great master, the kaśāya was an important emblem of the transmission of authority from master to chosen disciple." The kesa gives both legitimacy and power to the possessor whether it was an individual or a temple. Dusenberry quotes a passage from "...the rules of conduct for the monastic community...": "My disciple! Unfold a kaśāya as if it were a stūpa (funerary or relic mound), For it gives good fortune, extinguishes crimes and saves both human and celestial beings.... If a dragon wears even a single thread of one, He will be saved from being devoured by a garuda. If one wears a kaśāya in crossing the sea, There is no reason to fear dragon-fish or demons." (Ibid.) ¶ Dusenberry traces its origin back more than 2,000 years to ancient India where it was worn much like a sari is worn today. The rules of conduct "...detailed instructions for constructing, handling, and even washing a kaśāya. According to this ancient document, as explicated by Dōgen [道元 or どうげん], the ideal kaśāya was known as a pāmasūla (funzō-e in Japanese), which means, literally, 'excreta-sweeping robe.' It was to be constructed of 'discarded cloth' of ten types: (1) cloth munched by oxen, (2) cloth gnawed by mice, (3) cloth burned by fire, (4) cloth soiled by menstrual blood, (5) cloth soiled by childbirth, (6) cloth discarded at shrines, (7) cloth discarded in a cemetery, (8) cloth presented as an offering, (9) cloth discarded by government officials, and (10) cloth used to cover the dead. ¶ Monks were instructed to gather these scraps of soiled cloth with their left hands (the hand reserved in traditional Indian society for impure tasks), tear off any irrevocably stained portions, wash the rest, and construct a kaśāya from these segments." Buddhist scriptures stress that these bits of cloth are the purest that can be used. ¶ "Like the pure white lotus blossoms that rises from the muck of a muddy pond, the impure fragments of cloth are transformed through the process of construction into a sacred garment. This is a powerful metaphor for the transformation and resolution of apparent opposites associated with the experience of enlightenment." (Ibid., pp. 256-7)

Side notes: Funzō-e is 糞掃衣 - and if you would like to read more about the lotus please go to our web blog post at http://printsofjapan.wordpress.com/2009/09/13/the-lotus-蓮/ .

Mary Dusenberry notes that "Despite these regulations, extant kesa do not include examples of cloth picked up from the streets or soiled by childbirth or menstruatioin. In fact, most extant kesa are made of luxurious fabrics. The list [in the rules of conduct] "...can be interpreted to leave room for these luxurious kesa." Later Dusenberry tells us that "Even the most luxurious kesa, however, bear traces of the idea of a patched cloth made from discarded fragments." Even gold brocade is reminiscent of poverty in that "...poverty and frugality are necessary companions in the search for ultimate truth." (Ibid., p. 257)

"The Buddha Śakyamuni (the historical Buddha, ca. 560 - ca. 480 BCE)... instructed his disciple Ānanda to construct a rectangular garment based on the divisions of rice fields and levees, and to teach this construction to the other monks." The Buddha even specified the type of stitch, the backstitch. He also told his followers that they should only own three robes: The first shoule be of small and of five column and worn like a skirt when doing menial tasks; The second, medium-sized of seven columns was worn over the first for religious ceremonies; The third was of nine columns - eventually expanded to twenty-five - and came to be worn over the other two in colder climes or even worn over traditional garb where it "...took on a primarily symbolic function." In time the increase in the number of columns in China and Japan came to be associated with the rank of the owner. (Ibid.)

Dusenberry continued: "Over time, as Japanese Buddhit temples became ever more firmly entrenched in the fabric of society, the patched kesa beame, oddly, a symbol of the prestige, power, and wealth of the clergy." More and more luxurious Chinese fabrics were "...woven in complex new techniques, and from specially commissioned brocades and damasks with Buddhist motifs (such as the lotus) woven into rich surfaces." In time four small patches were often added in the corners not only to reinforce the garment, but also to represent the Shitennō (四天王), the Four Celestial Monarchs. These four corner patches may have appeared as early as the 8th century or they may have been added later for strength. However, by the 14th century they do start showing up and by the 17th century they had probably become part of the canon. (Ibid., p. 258)

The two kesa above are shown courtesy of Sri at http://srithreads.com/index.php. Click on the Japan link near the top of that page and then click on 'Kesa and Buddhist textiles' to see more examples. The rest of the site is great too and well worth exploring. |

||

|

|

||

|

Keshō |

化粧

けしょう

|

Cosmetics or makeup: Why and when women - and men - first wore makeup in Japan can only be speculation. Surely people painted their faces long before the development of cosmetics. Perhaps the firs occurrence was accidental and then ritualistic. Perhaps it was meant to emphasize ferocity or some kind of connection with the spirits both living and/or dead. What we do know is that by the Heian period members of the court aristocracy were codifying its use and it had become a symbol of class status.

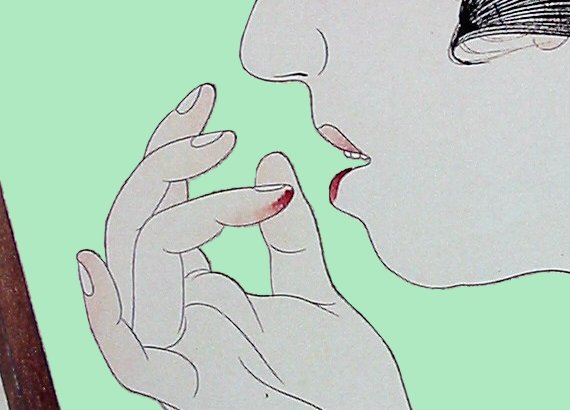

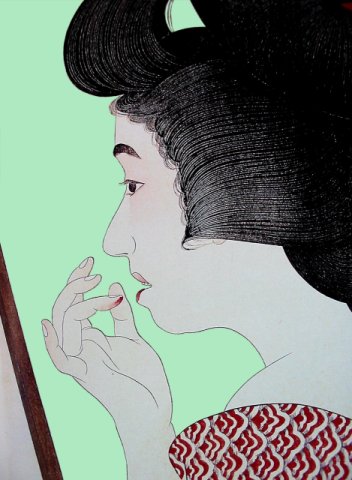

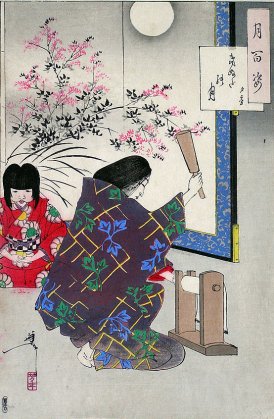

The above print of the "Eyebrow Penciling" from January 1928 has been contributed to this site by my dear friend M.

The images to the left are both details of a print by Kotondo (ca. 1930) entitled "Rouge". |

|

In a chapter entitled "Adopting the Caucasian 'Look': Reorganizing the Minority Face" by Masako Isa and Erik Mark Kramer the authors give a brief synopsis of the history of use of cosmetics in pre-Meiji Japan. "The manufacture and use of face powder, rouge, eyebrow paint, and other cosmetics were imported from the sixth century from Korea and China. In early times cosmetics were used only by special participants in religious ceremonies and festivals. Cosmetics were not worn for mundane adornment. The practice gradually spread among the aristocracy as a means of enhancing one's beauty. In the Heian period (794-1185) men as well as women used cosmetics."

Source: The Emerging Monoculture: Assimilation and the "Model Minority", by Eric Mark Kramer, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2003, p. 52.

In time new products arrived on Dutch, Spanish and Portuguese ships. (Ibid.) "Among the various compounds used, oshiroi [白粉], a white powder, and beni (rouge) [紅] contributed in constructing a woman's beauty. White powder was used to whiten the face and other parts of the body. The oldest form of face powder was made from white soil and rice flour. In the seventh century, the manufacture of keifun (mercury chloride) [けいふん] and empaku (white lead) [鉛白] was imported from China. Their use was confined to the upper classes until the seventeenth century, when it became popular among the general public." The empaku "...was used extensively during the Edo period... It was mixed with water and applied with a brush. In the 1870s, the toxic quality of lead was recognized, and soon after a lead-free facial powder began to be domestically produced." (Ibid.)

In A Treatise on Chemistry by Roscoe, Cain and Schorlemmer (published by MacMillan, 1913, p. 685) the production of keifun is described: "Calomel has long been known and manufactured in China and Japan under the name keifun (light powder). This product occurs as a light bulky powder, consisting of very thin minute scales, lustrous, transparent, and white or faintly cream coloured. It is quite free from corrosive sublimate and is manufactured by heating balls of porous earth and salt, soaked in bittern (the mother-liquor of partially evaporated sea-water), along with mercury in iron pots lined with earth. The forms hydrochloric acid from the magnesium chloride in the bittern, the mercury sublimes into the clay covers of the pots, air enters by diffusion and the following reaction occurs: 4Hg + 4HCl + O2 = 2Hg2Cl + 2H2O. The cover thus becomes filled with a network of micaceous particles of calomel."

There is an article on "Gender and Hierarchical Differences in Lead-Contaminated Japanese Bone from the Edo Period" from the Japan Society for Occupational Health (Journal of Occupational Health, vol. 40, no. 1, 1998). In this study it was found that members of the samurai class had far higher lead content in their systems than did that of farmers and fishermen. Women in both strata had higher lead deposits in their bones than did their male counterparts. In the abstract to this article it states: "We assume that facial cosmetics (white lead) comprised one of the main routes of lead exposure among the samurai class, because cosmetics were a luxury in that period." While male samurai may not have used white lead makeup they were exposed to it through their contact with samurai females and this accounts for the lead content found in their bones. In fact it would seem that the wealthier the samurai the higher the lead content.

One fascinating aside from this article that has nothing to do with Japanese cosmetic is the fact that: "The level of biological lead in the bones of a Peruvian buried 1,600 years ago was about one thousandth of the present-day American and British values." That was too interesting not to pass on to you here.

During the Heian period the practice of okimayu (置眉) began. This involved the shaving off the eyebrows and replacing them with fake ones painted on higher up on the forehead. At times both men and women of higher rank practiced this. Why? I haven't the slightest. It lasted, in one form or another until well into the Edo period.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Ketsubon kyō |

血盆経 けつぼんきょう |

The Blood Pool Sutra -

According to one scholarly paper the concept of the Blood Pool Hell

originated in China in the 10th century and came into Japanese thinking

during the Muromachi period in the 15th century. A very short sutra found in

the mass of Buddhist writings. Part of one of the translations of this sutra

reads:

Thus Mokuren used his holy

powers to come to the |

|

Keyaki |

欅

けやき

|

Japanese elm, Zelkova serrata: Hiroshi Yoshida in his Japanese Woodblock Printing (1939, p. 17) noted: "In olden times other kinds of wood, such as keyaki (Zelkowa serrata, Mak.), were inlaid in the block in order to give the benefit of the grain in special selected parts of the print." Silvio Bedini in The Trail of Time: Time Measurement with Incense in East Asia : Shih-chien Ti Tsu-chi (Cambridge University Press, 1994, p. 155) states: "The wood is used in Japan also for boatbuilding and the construction of temples. Because of its high oil content, the wood resists moisture and is greatly favored for cabinetmaking and inlay work." In World Woods in Color by William A. Lincoln (p. 130) notes that keyaki is resistant to insects and fungal attack. "It is durable." He adds: "In China and Japan the wood is used for building and maintenance of temples and is a protected tree reserved for this purpose.

The photo to the left above is shown courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. The one below it shows an example of the wood grain.

The value of keyaki is

brought home by an 1668 edict promulgated by the Edo government on the

heels of a major fire. It was to apply to a privileged set of samurai, the hatamoto. "Prohibition of the use of highly favored building

materials such as sugi and keyaki had a similar effect.

Normally doors in important chambers were made of the beautifully grained

sugi. Keyaki was hard, strongly grained timber prized for construction in

temples, shrines, castles, and residences, and preferred for the mon

which graced their entrances." (p. 271) The use of these materials, by

implication, would also be proscribed to ordinary townsmen. (p. 272)

However, "The hatamoto edict was reissued in 1699 omitting the prohibition

of the use of keyaki

Quote from: "Edo Architecture and Tokugawa Law", by William H. Coaldrake, Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 36, No. 3. (Autumn, 1981) |

|

Keyes, Roger |

ロジャー・キーズ |

Expert on Japanese prints, author of many books and articles. Keyes was married to Keiko Mizushima, who died at the age of 50 in Woodacre, California in 1989. She was exceedingly accomplished and could easily be described as a Renaissance woman.

Keyes was author or contributor to such important volumes as 1) Ehon: The Artist and the Book in Japan, 2) The Male Journey in Japanese Prints, 3) The Theatrical World of Osaka Prints, 4) The bizarre imagery of Yoshitoshi: The Herbert R. Cole Collection, 5) Japanese Woodblock Prints: A Catalogue of the Mary A. Ainsworth Collection, 6) Surimono: Privately Published Japanese Prints in the Spencer Museum of Art, nd 7) The Art of Surimono: Privately Published Japanese Woodblock Prints and Books in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin. 1 |

|

Kichō |

几帳

きちょう |

"Portable frame with thick decorated hangings behind which women normally sat when receiving callers."

Definition, i.e., quote from: The World of the Shining Prince: Court Life in Ancient Japan, by Ivan Morris, Kodansha International, 1994, p. 318.

"One piece of furniture which plays an important part in the literature of the time was the kichō, a six-foot portable frame supporting opaque hangings, which Waley translates as 'screen of state'. The hangings were attractively decorated, the material and the patterns being changed with the seasons. The bottom part was left unsewn, so that objects could be handed through the opening. The main purpose of the screen of state was to protect the ladies of the house from prying eyes. When receiving a gentleman caller, a woman normally ensconced herself behind these curtains where, at the best, she could be seen only in dim outline."

Ibid., p. 32.

Note: The graphic is my creation as are the decorative touches which have nothing to do with genuine, historical authenticity. While the kichō rarely shows up in ukiyo prints, however when it does appear infrequently it is in the works of artists who are trying to capture something of the Heian period. Eishi more than others seems to have used this prop in both his book and full, oban sized prints. At other times the kichō is an unobtrusive addition to a painting of a beautiful woman. |

|

Kihada |

黄蘗 (or 黄檗?)

きはだ

|

A rich, creamy yellow colorant obtained from the inner bark of the Phellodendron amurense or Amur corktree. (Phellos is Greek for cork and dendron means tree.) A member of the Rutaceae or citrus family.

The image of the bark to the left is used courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. |

|

"The thick trunk of Amur Corktree, while having a relatively smooth bark in youth, develops a deeply furrowed, ridged, and cork-textured bark with maturity, hence the common name."

Quoted from an Ohio State University web site on plants.

At a Virginia Tech web site there is a photograph of a piece of the bark showing the inner layers being held in the palm of a hand. The yellow color is startlingly strong in contrast to the pink of the person's flesh. Another site describes the yellow as 'neon'. It is clear from this image why the Japanese would have chosen it as a yellow dye. Now I wonder what process they had to put it through to extract the color and make it usable. Was it labor intensive or easy? The brilliance of the yellow would make it seem easy, but I don't know.

All of the web sites I have visited have noted that this tree is virtually pest free.

The cell color shown here is kihada yellow.

Don't forget that color descriptions are not exact. As there are many shades of green or blue for example, there are many slight variations within each of the colors shown here which may or may not conform precisely to your own perceptions of what they should be. |

||

|

|

||

|

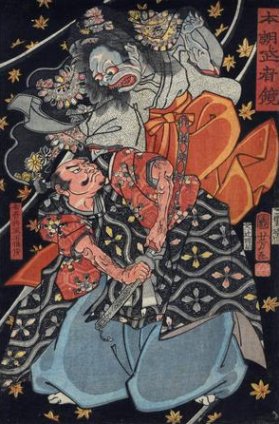

Kijo |

鬼女 きじょ |

Demoness, she-devil, witch, ogre - Lafcadio Hearn wrote: "Kijo, another Buddhist word signifying a kind of female goblin, appears in the common name of an orchid — Kijoran (goblin-orchid)."

See also our entry on hannya.

The Kuniyoshi image to the left shows Taira no Koremochi battling with a kijo. It is from the Lyon Collection. Click on it to see more information. |

|

Kikkō |

亀甲

きっこう |

Tortoiseshell motif used as a crest or mon. This is a basic hexagon shape which is often combined with other motifs generally encapsulated within each segment.

|

|

Kiku |

菊

きく

|

"The 16-petalled chrysanthemum is used as the crest of the Imperial Family of Japan, and the kiku is often called the national flower of the country. But the chrysanthemum was formally adopted as the Imperial crest only since the beginning of the Meiji era." However, the court had been using this flower as a decorative motif since as early as the 12th century.

There is a tale that in ancient China one of the favorites of the emperor was exiled because of an inadvertent transgression. Before he left the emperor told him to recite a specific Buddhist chant over and over after he leaves. "Living in the secluded mountain of Li-hsien, Tzu Tung faithfully repeated the passage every day. One morning he wrote the sacred words on a chrysanthemum leaf as he stood by a stream. The morning dew that collected on the lettered leaf fell into the water, and then a sudden change took place. The water became a sacred medicine to prolong life. Before the young man appeared a paradise of singing birds and fragrant blossoms, and angels came to wait upon him. With joy he drank the water of the stream, and lived for 800 years. All people living along the lower flow of he stream prospered and lived almost indefinitely." (Source and quote from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, pp. 353-4)

Merrily Baird in her Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design (p. 75) notes a noh version of this theme, but here it is the petals that are painted with Buddhist characters.

She also says that there are at least 95 different variations on the chrysanthemum crest or mon. To the left are just two of them.

Personal note: All of the coloring applied to any crests or mons is my choice. If I have crossed any cultural taboo lines then I apologize. But if I have done so it is totally out of ignorance and not even with a sliver of maliciousness.

Alfred Koehn in an article about Chinese flower symbolism quoted an old saying: ""Their autumn leaves were cut from emeralds, their cool flowers carved in golden jade." He added later: "The Chrysanthemum is the flower of Autumn, a symbol of Joviality, and it is associated with a life of Ease and Retirement." |

|

Kikusui mon |

菊水紋

きくすいもん

|

"An example of a mon story

focused on human sources of prestige is that of Kusunoki Masashige. His

brilliant defense of strongholds loyal to Emperor Go-Daigo was instrumental

in restoring the emperor briefly to power in the Kenmu Restoration

(1333-1336). Go-Daigo recognized Masashige by granting him a mon based on

the normally-restricted imperial chrysanthemum, showing it supported by

water. Go-Daigo explained that Masashige, in the same way, had kept him

afloat by his support.

The image to the left is a detail from a photograph posted at Flickr by Katie. |

|

Kikyō |

桔梗

ききょう

|

Chinese bellflower motif: John W. Dower notes that this "...is a five-petal, indigo flower which blooms in August and is known as one of the 'seven plants of autumn.' " Originally a wild flower that was eventually domesticated and grown in gardens. It was first worn as a warrior crest or mon in the 13th century because of its beauty. There are many diverse variations on this motif.

Source: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 48.

Kikyō can also be found under the term rindō (竜胆). Dower noted that "...the bellflower is one of the Japanese design motifs most adaptable to variation." These three examples don't even begin to show the breadth of differences between the various bellflower motifs. Some of them are hardly recognizable as such.

|

|

Family crest for the Akechi (明智) clan. It is always important to remember that other clans used one of the variations on this crest for their own personal use. For example, the Ōta (太田) daimyō used a kikyō displayed within a narrow, circular band.)

The photographic images are shown courtesy of Sue Shuehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. You should definitely visit that site. |

||

|

|

||

|

Kikugawa Eizan |

菊川英山 きくがわ.えいざん |

Artist 1787-1867 1 |

|

Kimedashi |

きめだし |

Detail from a Toyokuni III print. To see the full image click on the detail shown above.

"Kimedashi (heavy embossing) This is a bolder version of karazuri which produces a deeper but softer embossed mark on larger areas. It was frequently used in traditional prints to represent the bulging muscles of sumo wrestlers or the soft flowers of the cherry blossom. The method is the same for karazuri except that the thickish dampened paper is forced down into the texture of the block by pressing with a ball of cloth, an eraser or even the elbow rather than with a baren." (Quoted from: Japanese Woodblock Printing, by Rebecca Salter, University of Hawai'i Press, 2001, p. 110) In a book on the collection of prints at the Victoria And Albert Museum it states that kimedashi was produced through hammering as opposed to rubbing. A homonym for kimedashi describes a sumo fighting technique. |

|

Kimekomi |

極込 (?) きめこみ |

Synonymous with kimedashi, the entry shown above. There are at least three different types of blind printing or embossing: nunomezuri or fabric printing; karazuri; and kimekomi. In Cecilia Segawa Seigle's Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan (University of Hawaii Press, 1993, p. 147) notes a distinction between kimekomi and karazuri. She states that Harunobu used the former to give form to a whole figure while the latter was used "...for special effects for rich fabrics..." ¶ At a Brooklyn Museum web site they note that kimekomi gives a sense of volume to the area being embossed. They state that it is normally done with the key block - but not always - and pressure can be applied by the use of an elbow. |

|

Kinbaibai |

禁売買 きんばいばい |

'Not for sale': a term printed on some items indicating that they were probably given out as gifts. |

|

Kinchaku |

巾着

きんちゃく |

A Smithsonian publication from 1889 says that a kinchaku is "a pouch for child, suspended in the girdle".

Above is a detail from a print by Utamaro. The one to the left is from a print by Kuniyoshi. Notice the kinchaku in each.

Peter Constantine (and others) says that kinchaku can also be slang for a strong vagina. |

|

"There were two major turning points in the life of a child born (or adopted) into the buke [or military class]. The first was the introductory ceremony in which he was given his first sword, the mamori-gatana, 'a charm sword with a hilt and scabbard covered with brocade, to which was attached a kinchaku (purse or wallet)... worn by boys under 5 years of age...' " Quoted from: Secrets of the Samurai: The Martial Arts of Feudal Japan, p. 254.

"The dress of the Japanese having no pockets, if we except the recesses of the sleeves which cannot be used for anything heavy, it has been the custom from a remote era to attach to the girdle various objects of every-day service. Of these the oldest is the kinchaku, or money- pouch. Originally it was tied to the girdle, but subsequently another method of attachment was adopted, the string of the pouch being fastened to a button which was passed under the girdle and brought out above it so as to offer an effective obstacle to the withdrawal of the pouch without its owner's knowledge." Quoted from: Japan: Described and Illustrated by the Japanese, vol. 5, p. 161, edited by Frank Brinkley.

We have decided to quote the whole paragraph which includes a reference to kinchaku in Things Japanese by Basil Chamberlain (p. 125). It was too good not to do so. "Children's dress is more or less a repetition in miniature of that of their elders. Long swaddling-clothes are not in use. Young children, have, however, a bib. They wear a little cap on their heads, and at their side hangs a charm-bag (kinchaku), made out of a bit of some bright-coloured damask, containing a charm (mamori-fuda) which is supposed to protect them from being run over, washed away, etc. There is also generally fastened somewhere about their little person a metal ticket (maigo-fuda), having on one side a picture of the sign of the zodiac proper to the year of their birth, and on the other their name and address, as a precaution against their getting lost. Japanese girls do not, like ours, remain in a sort of chrysalis state till seventeen or eighteen years of age, and then 'come out' in gorgeous attire. The tiniest tots are the most brilliantly dressed. Thenceforward there is a gradual decline the whole way down to old age, which final stage is marked by the severest simplicity. Many old ladies even cut their hair short. In any case, they never exhibit the slightest coquciterie de vieillesse." Many other authors and experts, including contemporary ones, note the 'charm' element of the kinchaku. |

||

|

|

||

|

Kine |

杵

きね |

The pestle motif which was used as a family crest or mon. The pestle is associated with the pounding of mochi, a sticky rice cake made especially for New Year's. It has an extremely powerful religious symbolism to the Japanese. Also it is associated with the Japanese belief that the moon is the home of a large rabbit (or hare) pounding mochi.

It is my speculation, but it would seem that the pestle could easily be considered an instrument of strength and hence a potent symbol of power.

I have an admission to make: I made a mistake. The image to the left is a replacement for one I put there earlier. The first one was actually a pair of crossed tsuzumi, i.e., drums. If you go to that entry you will see the reason for my confusion. Just compare this new one with that one. |

|

Kingyo |

金魚

きんぎょ

|

Goldfish: I am a sucker for etymologies. So, although the term 'goldfish' is obvious I though I might be able to find a little more history about it by looking in the Oxford English Dictionary. I was wrong. It didn't give any. However, other sources did somewhat. But all of that is moot considering that the kanji character 金 means gold and 魚 means fish. It is a literal borrowing. Not from the Japanese, but from the Chinese.

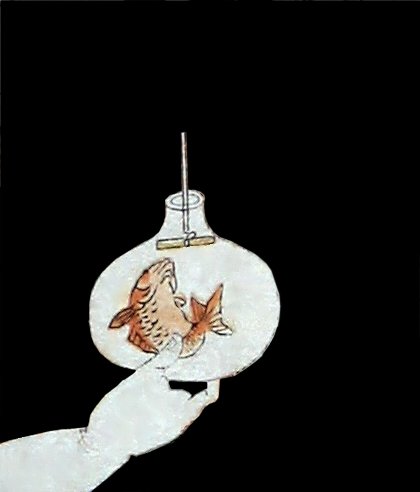

"It is presumed to be around the 11th century that goldfish breeding was conducted actively in China, and goldfish seem to have been imported to Japan on several occasions during the 16th and the 17th centuries." There was a 'goldfish boom' during the Genroku period (1688-1704). Later during the Bunka and Bunsei eras (1804-30) ukiyo artists used them as a creative motif."

Source and quote: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 3, entry by Saitō Shōji, p. 43.

"The practice of scooping for goldfish at temples and shrines on special days on special days and summer evenings began during the Meiji era."

Quoted from: Japanese Tradition in Color & Form [Pastimes]. Graphic-sha Publishing Company, Ltd., 1992, p. 121. |

|

Kinmedai |

金目鯛 きんめだい |

The name of a fish, often used for sushi. Splendid alfonsino or Beryx splendens.

The dish shown above is kinmedai Nizakana (煮魚), i.e., fish simmered with soy sauce (and sugar). We found this image posted at Wikipedia commons by Brücke-Osteuropa. |

|

Kinpaku (also kimpaku) |

金箔

きんぱく |

Gold leaf - There were two types of gold leaf available, entsuki (縁付) and tachikiri (断切り). The cost of the leaf is set by the kind of paper used to sandwich it and not by the gold itself which is always the same. Tachikiri paper is made more quickly and it contains sulphates and carbon to prevent static. Up to a thousand sheets at a time are cut using this paper while individual sheets of gold are cut when speaking of entsuki.

The image to the left if from a ja.wikipedia site of processed gold from the Kanazawa Gold Factory. |

|

Kinuta |

砧

きぬた |

A wood or stone block for beating cloth; a fulling-block.

This image was posted at commons.wikimedia by Tkunawan.

There is a nō play by Zeami called Kinuta. |

|

"Kinuta is the shortened word of kinu-ita (cloth-fulling block). Cloth is beaten or fulled with a mallet on a board to give more gloss or to soften starch in it. The sound has its own pathetic tone and it has been used in poems, songs or paintings as a tasteful subject from old times. Tea people also pay attention to kinuta when making an assortment of tea things in the autumn. Just a kinuta-shaped flower container might work. There are some theories as to the origin of the name kinuta seiji. A flower container Yoshimasa owned was kinuta-shaped, or Rikyû's flower container was in that shape, or Rikyû's flower container had a crack which had a particular sound when struck. It was produced in China at either Ryûsen-yô kiln or Ka-yô kiln." Quoted from; Chado: The Way of Tea by Sanmi Sasaki, p. 534.

In the Autumn of 1684 Bashō wrote:

beat the fulling block, make me hear it - temple wife

Yosa Buson wrote a poem which relates to that of Bashō:

as I am melancholy beat the fulling block, but stop now, it's enough

In a footnote to this poem it says: "In classical poetry it [the kinuta] was associated with the melancholy and cold of long nights in autumn, as poets wrote of hearing its lonely sound on a sleepless night on a journey, and thinking of loved ones far away."

Yoshitoshi used the theme of fulling in one of his 100 Views of the Moon. We found this image at commons.wikimedia.

We are not linguists, but we have noticed that many sources state that 'kinuta' means 'to pound silk.' In The Noh Theatre of Japan by Ernest Fenellosa and Ezra Pound translates the name of one particular Nō play, Kinuta, as 'The Silk-board'. In Himalayan Languages: Past and Present, James S. Matisoff, an accomplished linguist, says: "Instead of using kanatoko 'anvil' (lit. "metal-bed"), for the bone of the ear, Japanese uses kinuta 'fulling-block' < kinu 'silk' + uta 'to pound'), [sic] a wooden block on which silk cloth was spread and pounded in order to straighten the fibers and increase their gloss." However, we are unable to confirm this concept of pounding silk. Not only that, we find that this idea is repeated numerous times at Internet web sites. Repetition does not make something so. Silk as well as any other fabric could be pounded on a kinuta There is no reason to romanticize this word. |

||

|

|

||

|

Kirazuri |

雲母摺

きらずり |

"...mica printing to obtain a silver tone in the print."

Quote from: Japanese Print-Making: A Handbook of Traditional & Modern Techniques, by Toshi Yoshida & Rei Yuki, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1966, p. 168.

The example to the left is from a Kuniyoshi print which we have already sold. It shows a subtle use of such highlighting. Click on the number one in the column to the right to see the full print. 1 |

|

Rebecca Salter in her Japanese Woodblock Printing published by the University of Hawaii in 2001 (p. 112) states that the prints of Sharaku best illustrate the use of mica. "Mica was used because silver was too expensive and in many ways it was better because it did not discolour as easily. The background was often printed in a dark grey before being overprinted with nori or nikawa and sprinkled. Excess mica is lightly shaken off, the print allowed to dry completely and then brushed gently.

The same technique can be used for gold, silver or bronze powder. If the mica or powders are mixed with nori/nikawa and/or pigment and printed directly they lose a lot of their sparkle.

In some prints the mica printed area was crumpled (momigami) and then flattened out again by re-sizing the back of the print and pressing flat with a baren. The effect was rather like the crazing in an old Chinese ceramic glaze." [This last technique mentioned is one that absolutely drives me crazy - in a good sort of way.]

See our entry on mica or unbo on U thru Yakata-bune index/glossary page. |

||

|

|

||

|

Kiri |

桐

きり

|

The kiri tree (Paulownia tomentosa) in the West is known as the paulownia. Large purple flowers bloom in the early spring before the leaves even appear. The effect is quite dramatic. However, to the researcher as opposed to the casual viewer it is its nomenclature which is most surprising. When the Swede Karl Thunberg visited Japan he named it Bignonia tomentosa in 1783. (Its winged seeds, opposite leaves and large showy flowers led Thunberg to put it in that genus.)

In 1835 Siebold and Zuccharini named it the Paulownia imperialis after the Queen of the Netherlands.* Endlicher moved it in 1839 to the Scrophulariaceai family because the seed pod contained an endosperm. Now even that attribution is in dispute. Some botanists seem to think it lies somewhere between the two genera.

*Anna Paulovna Romanov (1795-1865), daughter of Tsar Paul I and granddaughter of Catherine the Great, married the future Willem II of the House of Orange in 1816. She was Queen of the Netherlands from 1840 to 49.

William A. Lincoln in his World Woods in Color (Linden Publishing Co., Inc., 1986, p. 143) "It has a fine straight grain and smooth even texture. "Weak in all strength properties, which are unimportant in the uses to which it is best suited." "Kiri is highly valued in Japan for a wide range of uses including cabinet and drawer linings, musical instruments, clogs, floats for fishing nets, and for peeling into exceptionally thin 'scale veneers', mountedon paper and printed to produce special visiting cards..." In the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan (vol. 6, entry by Matsuda Osamu, p. 166) notes: "The tree has a wide variety of other uses as well: the wood is burned to make charcoal for sketching and powder for fireworks, the bark is made into a dye, and the leaves are used in vermicide preparartions". |

|

In 1888 the Meiji Emperor established the Grand Cordon of the Order of the Rising Sun, Palownia Flowers (勲一等旭日桐花大綬章) which is only given to men of the highest rank such as admirals, generals, diplomats, jurists and politicians. It has even been bestowed on foreigners. General Douglas MacArthur (マッカーサー) received it in 1960 and later Mike Mansfield who acted as the American ambassador to Japan from 1977-88.

This entire entry originated from my rereading of "The Tale of Genji". The first chapter is Kiritsubo (桐壺). Royall Tyler (ロイヤル・タイラー) in 2001 translates this as "The Paulownia Pavilion", Seidensticker in 1975 as "The Paulownia Court", Suematsu Kenchō (末松謙澄) in 1882 as "The Chamber of Kiri" while Waley (ウェーリー 1925) and McCullough (1994) just call it "Kiritsubo".

The images to the left have been generously provided by Sue Shuehiro. Please visit his extensive botanical site at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. Compare the shape of the large leaf at the bottom and the cluster of flowers above with the kirimon featured in the section below. There is also additional information there about this greatly revered tree. |

||

|

|

||

|

Kiri seal |

桐紋

きりもん

|

The paulownia, i.e., kiri was the most popular of Japanese crest motifs. "According to Chinese legend, the mythical phoenix... alights only in the branches of the paulownia tree when it comes to earth and eats only the seed of the bamboo."

"As an explicitly imperial crest, the paulownia ranks only slightly behind the chrysanthemum, and both are usually taken as the dual emblems of the Japanese throne." In the early 13th century the emperor Godaigo (後醍醐) bestowed both crests upon the head of the Ashikaga (足利) clan. With that the bestowing of the paulownia motif was also an Ashikaga prerogative which they used to reward loyalty. The recipient clans wore it as a symbol of "legitimacy and power." In the 16th century, Hideyoshi (秀吉), who was born a commoner, after adopting it as his own crest also gave out the motif to some of his most loyal supporters. By the late feudal period nearly 20% of the warrior class wore it as their own personal crest.

Source and quotes from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, pp. 68-9.

Farmers once planted kiri trees upon the birth of a daughter because it was so fast growing that by the time she was ready to marry the tree could be cut down and made into a tansu (箪笥)or chest.

|

|

"The name kiri came from the kiru (to cut) [切る] as it was believed that the tree would grow better and quicker when it was cut down often." It can grow to more than 30' in height and has fragrant purplish blossoms in April or May.

Source and quote from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, pp. 358-9.

The image to the left on the bottom is the seal used predominantly by Kuniyoshi. It is important to note that he did not always use it and that certain students of his also used it occasionally too. 1 |

||

|

|

||

|

Kiseru |

煙管

きせる |

Naturally the habit of smoking (tobacco) was introduced into Japan by the Europeans in the 16th century. One familiar with the pipes used can't help but notice that the bowls are extremely small allowing for only a 'hit' or two before being emptied of ash and being refilled. A lot of my contemporaries have commented how much the bowl looks like the ones used for hash pipes. (That's right - hash pipes.) However, scholars are convinced that the bowls were originally designed like this because of the strength of the tobacco being imported. Besides, it would probably save quite a bit of expense if the tobacco was consumed in smaller quantities.

According to Mock Joya the longer more elaborate pipes - up to three feet long -were generally used by women and then only indoors. Click on the number 1 to the right and notice that it is a man holding the pipe and not only that but he is represented as being outdoors.

Source and quote from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, pp. 267.

The bowl of the pipe is called a gankubi (雁首), the stem is the rao (羅宇) and the mouthpiece is a suikuchi (吸い口).

The image to the left is a detail from a diptych by Toyokuni III. The actor holding the pipe is playing a character who was born ages before the introduction of tobacco into Japan. Hence, the pipe is an anachronism. 1 |

|

According to Classical Weaponry of Japan by Serge Mol (Kodansha, 2003, p. 187) early pipes might just hide small, but effective blades. They were so small - think of the size of the standard smaller pipe - that one would have to be incredibly close to the victim to be able to cut an artery quickly and with total surprise. I knew from past readings that early hairpins could also double as weapons for vulnerable women, but not the shorter men's pipes. I suppose almost anything could be cleverly disguised as an ordinary object while secretly doubling as a lethal instrument. But somehow this seems so reminiscent of a Charlie Chan movie and to have sprung from the mind of a mystery writer. Mol calls these shikom kiseru (仕込煙管). "Because the stem of the pipe was slender, it could not conceal much more than a spike or needle-like weapen." Mol notes: "Pipe tobacco was carried in a small pouch (tabake-ire), and the pipe was in a separate case called kiseruzutsu, or kiseru-ire, which could be made of leather, wood bamboo or papier-mâché. Pouch and case were usually tied together and the set was known as dōran. Some pipe cases, however, did not contain a pipe but held a short dagger. These trick pipe cases are known as shikomi kiseruzutsu (仕込煙管筒) or shikomi kiseru-ire (仕込煙管入), and the set is called dōran shikomi no kakushibuki or shikomi dōran (仕込胴乱) . ¶ The author notes that there are numerous other deceptive uses of disguised items: a shikomi writing set; shikomi flute; shikomi fan; etc.

In Smoke: A Global History of Smoking by Sander L. Gilman and Xun Zhou (2004, p. 78) Barnabas Tatsuya Suzuki tells us that the Japanese were already using kiseru when the Dutch arrived in 1609. (The Japanese learned about tobacco from the Portuguese about a century earlier.) "Dutch traders even supplied silver kiseru and finely shredded tobacco to their colleagues in other colonies or trading posts in Asia." And by 1634 there are records that the Japanese were exporting tobacco to other countries. ¶ "Initially, tobacco was sold as whole leaves, not shredded. It was cut at the tobacco shop at the customer's request, or the smoker shredded the tobacco leaves at home. Later, finely shredded tobacco became available in the market. Shredded tobacco was normally carried in a folded sheet of pocket paper; at home, it was kept in a box. ¶ The first attempt to produce and sell cigarettes in 1869 was unsuccessful. "Cigarette smoking became popular only after M. Iwaya began to manufacture cigarettes in Tokyo in 1882, and 1890, when the Murai brothers established a cigarette factory in Kyoto." (p. 83) But the kiseru hung on as a 'useful' cultural artifact until after W.W. II.

Sir Edwin Arnold in a series of articles entitled Japonica in Scribner's Magazine in 1891 speaks exactly to an issue which I have tried to explain to my contemporaries: Why is the bowl of the pipe so small? Whenever I tell someone(s) that the bowl was used for single hits of tobacco I get either incredibly skeptical looks or looks of amazement. This is true especially of people who grew up during the hippie/drug culture days and had been used to smoking small amounts of strong pot or hash from such bowls. They either don't believe me or think I am trying to sugar coat some hidden Japanese secret. But Sir Edwin's quotes should clear this up: "To be quite Japanese, we will begin by taking from our girdle, the little brass pipes and silken tobacco bags, filling the kiseru, and inhaling one or two fragrant whiffs of the delicate Japanese tobacco. In their use of the nicotian herb, as in very many other things, the Japanese display a supreme refinement. [They] are content with this tiny pipe which does not hold enough to even make Queen Mab sneeze." They might load the pipe once or twice and then quit and are appalled at the Western practice of smoking large quantities at one sitting (or standing, if you like). Sir Edwin tells us that the Japanese are "...always wondering how we can smoke a great pipeful to the 'bitter end,' or to suck for half an hour at a huge Havana puro. 'Kiseru no shita ni doku arimas!' they say - 'At the bottom of the pipe there lives poison.' "

Two sources which I have come across both claim that the word kiseru originated in the region of Southeast Asia. Once says the word is of Cambodian derivation and the other says Annamese, which is close to the same thing, but give two different root sources. I can't vouch for either. |

||

|

|

||

|

Kisha |

騎射 きしゃ |

Equestrian archery - see also our entry on yabusame. |

|

Kitsune |

狐

きつね

|

Fox

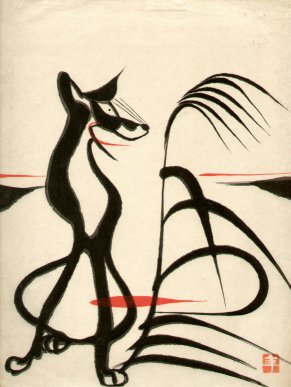

The top image to the left is a detail of a print by Koson, aka Shoson, from the first decade of the 20th c. The image below that one is probably from the early 1960s and is by Inagaki Toshijirō (稲垣稔次郎 - 1902-63), aka Nenjirō Inagaki. This image was sent to us courtesy of E. one of our great contributors. Thanks E! Both prints show the whimsy with which the Japanese treated the mischievous fox.

Recently a correspondent in Maine who we will call D. wrote and included several images of deer and foxes which he had taken in his own back yard. A couple of them were particularly good and it was difficult to choose, but I finally decided to post the one below. Although I am sure all of you know what a fox looks like I still think it is a good thing to be able to see a photographic representation next to those created by artists. True it is a Maine fox and not one from Japan, but beggar's can't be choosers. Thanks D!

|

|

There are foxes and there are foxes. Scientifically speaking there are various types of foxes.* The same is true of myths and folklore when dealing with this animal. U. A. Casal in his article "The Goblin Fox and Badger and Other Witch Animals of Japan" published in volume 18 of Folklore Studies in 1959 discusses several of these. "Savants tell us that there are a good many varieties of foxes, good, bad and indifferent. The common fox, kitsune, or field-fox, yako [やこ], hardly counts in lore, although it is of course not easy to know whether the animal in question is a simple yako or one of its more moody peers. Like the white foxes, the black ones, genko [げんこ], are friendly, and their appearance of a good omen. A red shakko [しゃ こ] is still fair, but the "field-shield" yakan is highly harmful. The air-fox kūko [くうこ] and the celestial-fox tenko [てんこ] are probably rather tengu of sorts, goblins that can fly through the air and of which it is best to beware, since the entire tengu-tribe can be very nasty. The ktūko and tenko seem rather Chinese conceptions, of no folkloristic importance in Japan..." (p. 3) There are also spectral foxes: "Written references to goblin-foxes does not seem to exist before the very early 11th century, in the well-known Genji Monogatari; a somewhat more definite reference to this type of magic foxes - some demoniacally powerful reiko [れいこ], ghost-fox, or some almost as dangerous koryō, haunting-fox - appears in a slightly later story-book, the Uji-shūi Monogatari, also of the 11th century." (pp. 1-2) Casal argues that such superstitions were imported into Japan because 1) he found no earlier native references and 2) the Chinese already held such views a thousand years before they appeared in Japanese literature.

In 1959 Casal wrote: "The Ainu, too, dislike the fox and avoid him as much as possible. This notwithstanding, the fox-skull with them is a fetish, set up on sacred posts outside their house to protect them from evil spirits." (p. 4)

However, in 1999 in a catalogue devoted to the Ainu put on by the Smithsonian it states: "Fox spirits are a matter of dispute among different Ainu groups, with some believing them to be helpful spirits while others see them as evil. Nevertheless, their skulls were often used as guardian spirits while others see them as evil. Nevertheless, their skulls were often used as guardian spirits for fishing, hunting, and daily life, and they were also used for fortune-telling. Whether it was believed that the spirits remained in skulls used for this purpose is ambiguous: theoretically, if they had been through a sending ceremony, they should have lost their active power; to be a guardian deity, its spirit must exist. Ethnography has not yet provided answers to such questions."

Quoted from: Ainu: Spirit of a Northern People, edited by Wm. W. Fitzhugh and Chisato O. Dubreuil, entry by Shigeki Akino, Smithosonian Institution and University of Washington, 1999, p. 252.

Casal tells the Ainu legend of the good and bad spirits getting together to decide which are going to rule the world. They finally fix on a scheme: The first spirit to see the sun rise will win for its side. The fox was considered one of the benevolent spirits. They all lined up looking east toward the horizon while the fox turned its back and looked westward. "The others of course poked fun at him; yet it was the Fox-god who first exclaimed: "I see the sun!" And indeed, when the others turned around, there was the brilliant sunshine reflected from a high peak in the West!" (p. 4)

In the first footnote in his article Casal notes that "The Chinese, but not the Japanese, nevertheless use the name "Fox" as a family-name. It has been surmised that this is due to ancient totemism."

*I claim no expertise here, but as I understand it there are four genera of foxes - Gray, bat-eared, Zorros and true foxes - made up of twenty-three species.

The fox can see into the future. It can find lost objects. Humans who are searching for such items will pray to Inari (稲荷), the fox-deity. (Inari was also originally the harvest god.) In China there is the story of a man who urgently needed to find one document in particular from among a multitude. Frustrated the man lit incense and prayed to the fox-god for help. Closed up the room and left for awhile. When he returned he noticed that one packet of incense stood out from the others and that this pointed the way to the document he was looking for. (p. 5) Anecdotes seem to work quite well as proofs for the superstitious.

Assuming human form: "A most frequent "trick" of the fox is to take on human shape. For this he needs a skull-preferably human-and a few old bones, of horse or cow, which he places on his head and holds in his mouth. He first goes through some mysterious performances, and decks himself out with leaves and grasses. Then he faces the North-star, and "worships." His genuflexions and obeisances begin slowly and circumspectedly, but their motion gradually increases in rapidity, until finally the fox seems to perform an "Indian dance", with jumps towards the star. Yet the skull does not fall off. After a hundred acts of worship, the beast becomes able to transform himself into a masculine human being; he is now a jinko, "man fox", but if he wants to be able to turn into a young and elegantly dressed girl it is essential that he constantly live near a grave-yard..." ( p. 6) Casal notes that the Chinese add a second way for a fox to take on human form: It can do good deeds or learn 'the classics'. (p. 7) "This human disguise may be transitory or semi-permanent. But only aged and wise foxes have power to act as people for a prolonged time; incidentally, age and wisdom do not imply benevolence." But wary Japaness have ways of detecting the fox-spirit disguised as a human. In the first place, some foxes give off an inner glow most noticeable at night. This inner fire can be so bright that the hair and kimono patterns can be seen clearly at six feet. Often, too, the 'human' face is unnaturally long.

Human speech: "Another important sign: the fox, while he can learn to talk like a human in a year's time, experiences some difficulty in pronouncing certain words or sounds. It is impossible for him, for instance, to say "moshi-moshi" in quick succession. He just manages to say moshi once, and it sounds somewhat awkward." Casal adds: "It is in order not to be mistaken for a bakemono-fox that true humans never use moshi .only once, but always double it: moshi-moshi! Not to do so would be quite impolite, as people might become scared at the contingency of being confronted by a spook-fox..."

The fox in human form also has another telltale give away. It has a 'faint shadow' which is the real thing. So, "It is therefore important, when one intends to kill a bakemono, that the thrust be not made at the human figure, but at the vapoury fox-shape!" One other thing I forgot to mention was that it doesn't hurt to have a dog with you when you go out. Dogs are never fooled. They always know when there is a transformed fox nearby.

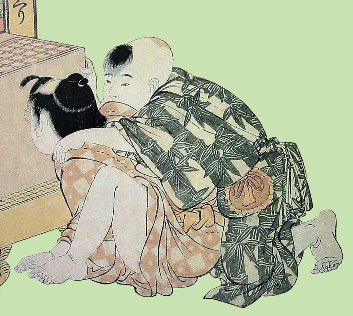

The beginner's mistake: Sometimes when a young fox has just learned how to transform itself into a 'human' it is filled with careless giddiness. (I am projecting here.) It has done his magic perfectly: Its face may be a bit long, but so what?; Its kimono is colorful and well composed; No real human will ever know. Except...except for one small oversight our fox might just pull off its ruse: Its tail is visible out of the back of the kimono. The Japanese have a phrase for this: Shippo o dasu (尻尾を出す) - To show one's true colors, to expose one's faults, To give oneself away. No self-respecting older fox would make this kind of amateurish mistake. (p. 8)

The people of Izumo think that when a transformed fox knocks on their doors it is always somewhat muffled because the fox knocks with its tail and not with its knuckles. (Ibid.)

Or, if you are walking along and encounter a fox-spirit which has taken human form you can determine whether this is a fox or a real persons by pinching yourself. Do it hard! Now, if you don't feel anything then you can be sure it is a fox which has bewitched you. However, if it does hurt then you can rest easy that this is only another human. Ouch! Or, you can always carry a fried rat with you just to be safe. Foxes love fried rats. In fact, they can't resist them. Casal says: "One other efficacious way to detect a bakemono fox is to depose a fried rat on the road along which the suspicious person comes: the animal is so fond of fried rats, that he will immediately abandon his prank and pounce upon the tidbit. "

Casal continues: "But, as usual with spectres and eerie animals, not all foxes are able to bakeru, to metamorphose themselves, to assume the garb and speech of humans, to bewitch people. At least so the savants say, although the common man prefers to avoid all kinds of foxes. Those who are better versed in their doings declare that only a red, white or yellow fox can ever hope to attain this stage; and before being "safe" in doing these things, he must escape the mortal danger of thunder three times, or be at least five-hundred years old." The older the fox the wiser it is. If it reaches 800 to 1,000 years it becomes a "Celestial Fox," takes on a golden color, has 9 tails and knows the secrets of Nature.

Above is a 9 tailed fox from a famous Kuniyoshi print. This is only a detail. I asked a friend who owns the original to send me an image. He did posthaste. I did the doctoring. Thanks friend!

Foxes which live in or near graveyards are the most dangerous because they develop a symbiotic relationship with human ghosts.

A major Chinese dictionary from ca. 100 A.D. says that the fox was the vehicle ridden by ghostly beings. (p. 9) In Japan "The fox-goblin may approach a lonely house as an old man who has lost his way, as a pilgrim-monk or Buddhist priest, or as a damsel in distress - rarely in any other human form." The monk or priest disguise bodes the worst for the mortal being that encounters it. "The most dangerous transformation, people believe, is when the fox becomes a bōzu [坊主], Buddhist priest. Perhaps only the very powerful beasts can adopt this saintly disguise." (p. 10)

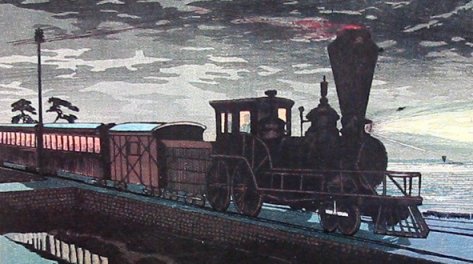

Fox-spirits and the machine age: "The weirdest of all fox-transformation stories is, I do not doubt, one of the most modern, dating from 1889. In that year it was widely circulated and believed that a fox had taken the phantom shape of a steam-train on the Tokyo-Yokohama line!" One day an engine-driver saw another train coming directly at him on the same track. Startled he blew his whistle and kept blowing it. But soon he noticed something very odd about the other train. No matter how far the engineer-driver went the other, approaching train never got any closer. Realizing what was happening the engineer decided to speed up instead of slowing down. "And at last he caught up with the phantom-there was a slight jar and, lo and behold! a fox was found crushed under the wheels..." (p. 12) Below is a detail of a print of a train by Kiyochika from 1889. Or, is it really a fox? Who knows?

You would think that the foxes would have learned from the train episode, but no. Sometime after the introduction of the automobile into Japan it happened again. A fox-car played chicken and the fox lost. (p. 13) Will they never learn?

I married a teenage fox: The most famous story of a human marrying a fox and fathering a child is that of Kuzonoha. Human animal marriages are called irui konin banashi ( いるい.こんいん.ばなし?). (For more on this theme go to our Yoshiiku Kuzunoha fox woman page.) Casal notes (pp. 16-17): "...it is said that the very name for fox, ki-tsu-ne, means "come and sleep", and is derived from such a tale dating back to the year 545..." A man from Mino waited a long time to find his ideal woman. One night he was crossing a moor and he met her. They married and had a child. His dog gave birth to a pup at the same time. As the pup grew it became more and more menacing to the fellows wife, but them man refused to kill the dog. Then "One day it attacked his wife so fiercely that in despair she resumed her proper fox-shape, jumped over the fence, and disappeared in the moor. Ono was crushed. But he loved his wife in spite of her fox identity, and "because she was the mother of his son." So he shouted after her that whatever she be he wanted her to "ki tsu ne"; and so, every night she stole into the hut and slept in his arms." (p. 17)

The image above is a doctored detail from a print on the Kuzunoha theme by Kuniyoshi. Our great contributor E. helped us by providing the complete print.

The fox can bestow the gift of kiki-mimi (ききみみ) on a human allowing him to understand the languages of birds and beasts. (p. 18) There are other foxes which can bestow wealth or prosperity. Sometimes there is a whole class of humans called fox-owners or kitsune mochi (狐持ち). However, families that fall within this category pay for this privilege in certain ways: They are social outcasts and are forced to stick to their own. They even marry within their group. To do otherwise means ostracism. But their ties to the foxes should guarantee them a certain level of security. Outsiders look at them and find that the only way to explain the success of this group must be their close bond with the foxes. In a footnote on page 20 Casal notes that Saul in the Old Testament drove out the people who possessed 'familiars': "...and Saul had banished from the land all who trafficked with ghosts and spirits." The cultural comparisons are clear.

"...fox-owning families are believed to have living with them a tribe of small, weasel-like foxes to the number of seventy-five, called human foxes [jinko], by whom they are escorted and protected wherever they go, and who watch over their fields and prevent outsiders from doing them any damage. Should, however, any damage be done either through malice or ignorance, the offender is at once possessed by the fox, who makes him blurt out his crime and sometimes even procures his death. So great is the popular fear of the fox-owners that anyone marrying into a fox-owning family, or buying land from them, or failing to return money borrowed from them, is considered to be a fox-owner too. The fox-owners are avoided as if they were snakes or lizards. Nevertheless, no one ever asks another point blank whether or not his family be a fox-owning family; for to do so might offend him, and the result to the inquirer might be a visitation in the form of possession by a fox. The subject is therefore never alluded to in the presence of a suspected party. All that is done is politely to avoid him." (p. 21)

Yamabushi (山伏), literally 'one who lies in the mountains', were ascetic monks who were said to have magical powers. They often blew a conch shell trumpet or horagai (法螺貝) "...to convoke a meeting and also to dispel evil ghosts on the road..." and to call foxes to them to be their servants. "According to the "savants", the yamabushi had several types of helpers: the kiko or spirit-fox as a general assistant in sorcery; the osaki-kitsune, whose written name means "tall-promontory", but should probably be but a 'tail-tip', of very small size; and the even smaller kanko or kuda-kitsune, the "pipe-fox", because it could be enclosed in a bamboo tube and carried in the hand by the yamabushi while on his pilgrimage! Whatever their size, these foxes, being the most powerful of all goblins, through their presence in a holy cause would then dispel and vanquish all inferior spirits." (pp. 24-25) |

||

|

|

||

|

Kitsunebi |

狐火

きつねび

|

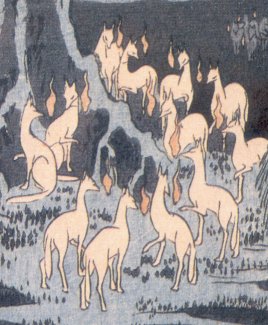

Foxfire (St. Elmo's Fire): "Indeed, foxes are very fond of luring people to an unholy place by creating a welcoming light or 'fire', so fond that the ignes fatui are called kitsune-bi, 'fox fires'. The fire is produced by the fox striking the ground with his tail, or it may also be his luminous breath. It will either burn quietly, like a lamp, to attract the intended victim into a phantom house, or it will wander about like a torch and confuse the late traveller, sometimes ensnaring him into an inextricable forest or a swampy moor. At other times the beckoning flame will promptly extinguish at the approach of the victim, leaving him in complete darkness far away from the road. Or it may suddenly 'fly away and disappear in the sea'... The breath-exhaled fire may even 'shoot forward to the distance of some two or three feet'. . . "

Quote from U.A. Casal, "The Goblin Fox and Badger and Other Witch Animals of Japan", Folklore Studies, vol. 18, 1959, p. 10.

To the left we have added a new image by Kunisada of the kitsunebi. For a discussion of the iconography of this image go to our page devoted to Yoshitaki's Yaegakihime.

Go, too, to our entry on hitodama on our Hil thru I index/glossary page for a further discussion of flames which float in the air. |

|

Kitsune ken |

狐拳 きつねけん |

This is a rock, paper, scissors game where the loser has to drink a cup of saké or do some such thing. It can also be played like strip poker. |

|

Timothy Clark describes an Utamaro print from ca. 1793-4: "Three tea-house beauties of the day are playing the party game 'catch the fox' (kitsune ken), with the forfeit that the loser has to drink some saké. In 'catch the fox', three contestants face one another and compete making gestures simultaneously to represent one of three types: a hunter with a rifle, a squire and a fox. The hunter beats the fox, the squire beats the hunter and the fox beats the squire..."

Quoted from: The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, Text volume, p. 122. |

||

|

|

||

|

Kiwame |

極め

きわめ |

The major censor's seal used from ca. 1790 to 1842. Literally this term translates as "investigated thoroughly." 1

In talking about the sale of a series of Hiroshige prints in 1916 Arthur Baldwin Duel said: "Many expert believe the Kiwame stamp to be the publishers' guarantee that the prints on which it appeared were by the artists whose names were signed to them."

Hepburn in 1903 defined kiwame as "To define, determine, decide, fix, establish, settle; to end, finish, exhaust; to carry to the utmost; to investigate thoroughly..."

Basil Stewart who was extremely opinionated and often wrong translated kiwamé as "perfect". |

|

In The Artist As Professional in Japan Julie Nelson Davis wrote on page 117: "When required by the bakufu, approval by the publishing guild is seen in the inclusion of the kiwame (guarantee seal), otherwise known as the censor's seal."

In Nelson's Japanese-English Character Dictionary it defines kiwa(meru) as "investigate thoroly". Note: We use and trust Nelson, but his use of 'thoroly' which does not appear in any acceptable dictionary does give us a reason to pause. |

||

|

|

||

|

Koban |

小判

こばん |

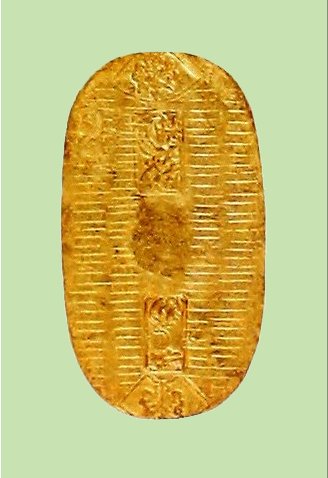

An oval gold coin: Chinese coins from 300 B.C. to 300 A.D. have been found in archeological sites in Japan and are mentioned in the Nihon Shoki (720). The first Japanese coins were issued in 708, but the Bureau of the Mint or Chūshenshi was abolished in 987. It was centuries before any more attempts were made to establish a financial system grounded in hard currency. Then in the late 16th century Toyotomo Hideyoshi introduced a large, no huge, gold coin called an ōban. It was nearly 6" long by 4" wide. Hideyoshi also minted more manageable copper coins. ¶ Because the ōban was more symbolic than practical Tokugawa Ieyasu introduced the smaller koban. It has been described as being valued at anywhere between 1/10th and 1/7th that of the ōban.

Source: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 5, p. 242.

Gold coins show up occasionally in ukiyo prints. In fact they form a rather odd sub-genre. I use the word 'odd', but you will see for yourself.

The image I have known the best over the years is the one of a figure striking a water basin and having gold coins spew forth. There are a number of variations on this theme, including one of a woman named Umeage praying for just such an event when she is overheard by a customer of a nearby business. He takes pity on her and showers down the gold coins she is hoping will be miraculously bestowed. However, I have yet to find the earliest version of this story. |

|

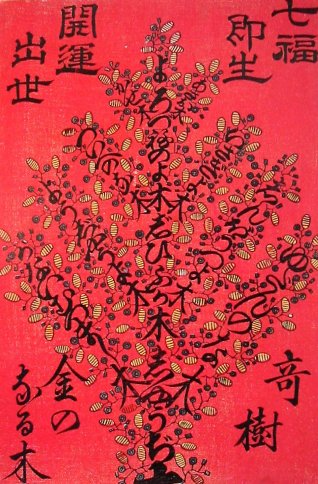

Who says money doesn't grow on trees? - at least metaphorically The image above is from the top half of a Yoshitoshi vertical diptych. There are numerous other examples of the Meiji period of the use of this motif by other artists. Note that the branches of the tree are made up of script, i.e., writing. This is a much older convention. |

||

|

In the U.S. we have a saying "That ain't chicken feed." There is also "Pennies from heaven", a phrase popular during the Depression when a penny meant something. I have no idea what is happening in this early 19th century book illustration. You tell me.

|

||

|

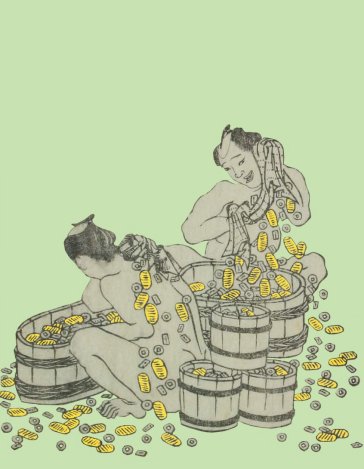

Then there is bathing in it. Imagine. To be 'awash in money'. As a child I loved comic books. In one of them Scrooge McDuck is shown sitting atop a mountain of coins pouring them gleefully over himself. Toyokuni I illustrated this more graphically at least 140 years earlier - sans duck.

|

||

There is a Japanese saying: "Neko ni koban" 猫に小判 translating as 'Gold coins to a cat', but comparable to the Western adage: 'Casting pearls before swine'. |

||

|

|

||

|

Kochōsō |

胡蝶装 こちょうそう |

Butterfly-binding: "It was also during the Tang that the so-called 'butterfly binding', kochōsō 胡蝶装 came into use, and was subsequently transmitted to Japan. This involved folding each sheet of paper in half and laying it on its predecessor and then gluing a cover to the folded edges: it derives its name from the fact that when opened each pair of pages tends to stand up with an effect resembling the wings of a butterfly. This technique was mostly used for printed books, unlike the yamato-toji 大和綴 (also known as techōsō 綴葉装), a technique that appears to have no parallel in China and to have been developed independently in Japan. In this the folded pages were placed one inside the other until a fascile or booklet had been formed, whereupon thread was used to sew them together along the fold, several of these fasciles being put together to form one volume. This technique was widely used from the late Heian period onwards, and particularly for manuscripts of Japanese literary works. By the Tokugawa period it was seldom used for printed books, except for the Nō texts published in Saga in the first half of the seventeenth century... and some Buddhist texts pertaining to the Jōdo sect. It continued, however, to be used for manuscripts, mostly for luxury productions intended as bridal gifts (yomeiribon 嫁入り本) or for the collection of daimyō and members of the court aristocracy in Kyoto." Quoted from: The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth Century by Peter Kornicki, pp. 43-44. |

|

"From the late Tang to the early Song, printed books gradually replaced manuscripts, and album leaf replaced the scroll system. ¶ Album leaf refers to binding several single leaves into a volume suitable for printing. The earliest album leaf system was butterfly binding, which evolved into wrapped-back binding and then stitched binding. When machine-based printing was introduced, binding gradually moved to paper and hard-cover binding.... ¶ The name butterfly binding emerged from its resemblance to a butterfly when the book was spread out. It was the main layout system used during the Song dynasty. In butterfly binding, two pages were printed on a sheet, which was then folded inwards. together at the fold to make a codex with alternate openings of printed and blank pairs of pages. A hard cover (sometimes coated with cloth or silk) was made . In appearance, it looked like a modern paper or hardcover bound book and the shape of the leaves and the manner in which the book opened and closed resembled the wings of a butterfly." Quoted from: Chinese Publishing by Hu Yang and Yang Xiao, pp. 74-75. |

||

|

Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan |

講談社日本百科事典 |

A wonderful nine volume encyclopedia of Japanese culture for a general but quick reference point. 1 |

|

LINKS TO OUR OTHER INDEX/GLOSSARY PAGES Click on any of the pages listed below!

|

||

_Factory_wikipedia.jp_7b.jpg)

HOME

HOME