|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

J thru Kakure-gasa |

|

|

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Jakago, Janome, Janome-gasa, Japanese names, Japanese Woodblock Prints: Artists, Publishers and Masterworks 1680-1900, Jigoku, Jigoku Dayū, Jimbaori,

Jingasa,

Jiraiya Goketsu Dan, Jisei, Jitsubushi, Jitte, Jizai kagi, Jizō, Jizuri, Jō, Jō and Uba, Jōe, Jōhari no kagami, Jōi, Jōkamachi, Jōkyō, Jomon, Jōō, Jūnihitoe, Jūnishi, Junshi, Jūō, Juzu, Kabuto, Kabuki-za, Kaede, Kaemon, Kaeru, Kaerumata, Kagami, Kagami biraki, Kagamibuta, Kagami mochi, Kagaribi, Kage-e, Kagema, Kagerō, Kago, Kagome, Kaguyama, Kai awase, Kaiba, Kaimamiru, Kaimei, Kaimyō, Kaiseki, Kaishi, Kaji, Kaji no ha, Kaitai shinsho, Kakeawase, Kake-gō, Kakejiku, Kakemono, Kake soba, Kaki, Kakihan, Kaki shibu, Kakitsubata and Kakure-gasa

蛇籠, 蛇の目, 蛇の目傘, 地獄, 地獄太夫, 陣羽織, 陣笠,

辞世, 地潰し, 十手, 自在鉤, 地蔵, 自摺, 上, 尉 and 姥, 浄玻璃の鏡, 攘夷, 城下町, 貞享, 縄文, 承応, 十二単衣, 十二支, 殉死 , 十王, 数珠, 歌舞伎座, 兜, 楓, 替紋, 蛙, 蛙股, 鏡, 鏡開き, 鏡蓋, 鏡餅, 篝火, 影絵, 蔭間, 蜻蛉, 駕篭, 籠目, 香具山, 貝合せ, 海馬, 垣間見る, 改名, 戒名, 懐石, 懐紙, 解体新書, 梶, 梶の葉, 懸合せ, 掛香, 掛軸, 掛物, 掛け蕎麦, 柿, 書判, 柿渋, 杜若 and 隠れ笠 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Jakago |

蛇籠

じゃかご

|

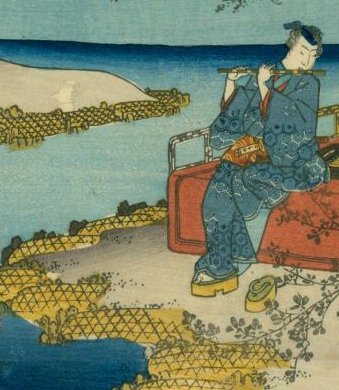

Gabion: Wicker containers which are filled with stones to help prevent erosion along breakwaters, jetties or river banks.

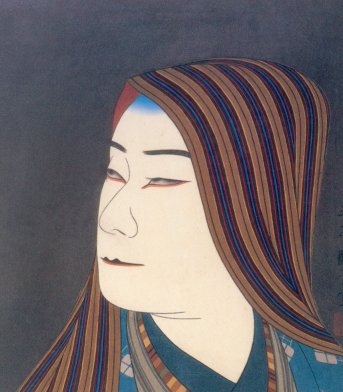

The image to the left above shows a detail of a Kuniyoshi bijin wearing a robe decorated with gabions. The one to the left below was sent to us by our generous contributor Eikei (英渓). It is a detail from a print by Sadahide (貞秀) ca. 1847-8 showing a fellow sitting by a river lined with jakago. Thanks Eikei!

The kanji 蛇籠 when parsed can mean 'snake' (蛇) plus 'basket' (籠).

|

|

Janome |

蛇の目

じゃのめ

|

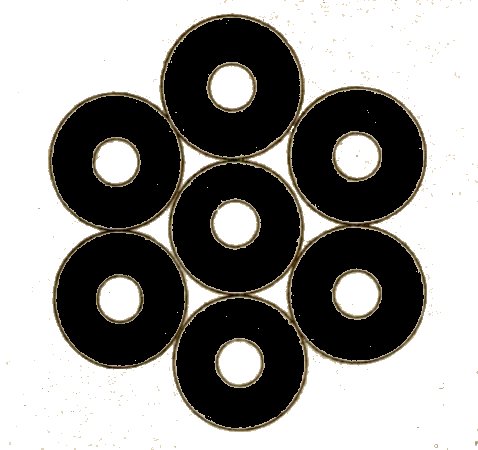

Bull's eye or snake's eye motif used as a family crest or mon. It is also the name of a type of umbrella which has that design as part of its structure. At the left are just two of the variations of this motif.

The kanji character 蛇 by itself means 'snake'.

"This motif was originally called tsurumaki, or 'bowstring spool,' because of its resemblance to the device on which warriors wound their bowstrings when the bow was unstrung. The spool was generally hung from the warrior's waist from his large sword by a loop run through the hole in the spool center."

Quote from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, published by Weatherhill, 1991, p. 134.

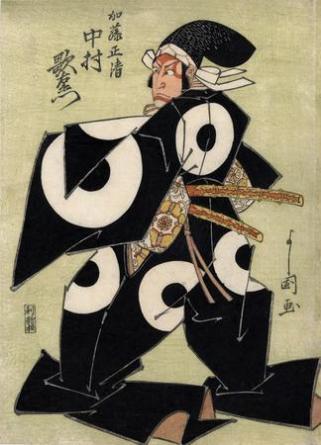

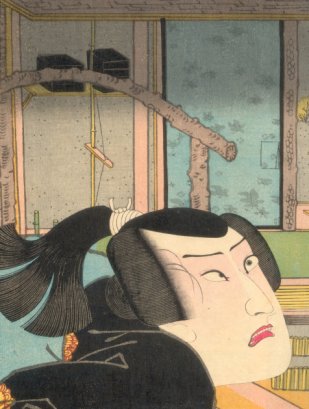

The image to the left below is from the Lyon Collection. It shows Nakamura Utaemon III in the role of Katō Masakiyo in an 1820 print by Yoshikuni. Katō Kiyomasa (1562-1611) used this symbol as his crest.

[The janome was] "...originally modeled after tsurumaki, a leather, ring-shaped spool used to reel bowstring. The tsurumaki [弦巻] was an essential part of a samurai's battle gear. Later, the design came to be called janome simply because of its resemblance to a snake's eye. It was usually adopted by samurai families for its warrior symbolism." Quoted from: Family Crests of Japan, p. 94. |

|

Janome-gasa |

蛇の目傘

じゃのめがさ

|

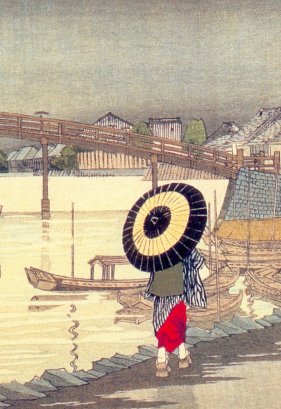

"...it is not surprising varied according to gender, rank and even geography... The janome (snake's-eye) type with black, brown, or indigo paper and a white center band came into fashion around the Genroku era (1688-1703); orange and red janome seem to have become popular much later. Among men, the janome was rarely used by the samurai class but was favored by monks and doctors. In the Osaka-Kyoto region, janome were used by women of samurai status; their umbrellas, always held by female servants, had long sticks and large covers. In Edo, however, even if a woman had two or three servants, she carried her own umbrella, and the stick was accordingly shorter."

Quote from: Rain and Snow: The Umbrella in Japanese Art, by Julia Meech, published by Japan Society Inc., 1993, p. 52.

The image to the left above is a detail from a print by Kiyochika from 1876 while the one below is from a print by Kunisada showing an actor carrying a janome from the 1830s.

|

|

Japanese names |

|

If I were a person who pulled his hair out when frustrated I would have been bald as a bowling ball years ago. Personally I find Japanese names confounding and almost completely inexplicable and worthy of self-abuse, but... Anyway, I was reading the preface to Japanese Names by Koop and Inada, which was first published in 1923, where they stated that "...the existing literature on the subject is confined to a few short articles in such works as Chamberlain's Things Japanese..." So, I went there and the information listed below is based initially on that source. |

|

1. "The kabane [姓 ] or sei [姓], a very ancient and aristocratic sort of family name.... The grand old names of Minamoto, Fujiwara, Tachibana, are kabane." (Chamberlain, p. 345) From the 5th thru the 7th or 8th century there were two types of family names: uji for clans and kabane. The kabane were divided into various subgroups each indicating either the persons direct relationship to the imperial family or services performed for it. These titles were hereditary.

"One of the most important foundations of the Ritsuryō state was laid in 684 by the Emperor Tenmu. Tenmu instituted an eight-rank kabane (hereditary title of nobility) system, which reorganized the tradition court rank system by granting a higher degree of status to those uji who had made useful contributions to the throne." (On Understanding Japanese Religion, by Joseph Mitsuo Kitagawa, p. 110) The emperor could have abolished the kabane system and replaced it with something else, but instead he kept it without punishing his enemies while using it to benefit his supporters.

One other note to keep in mind: If you don't actually know the family, person or place being named - using kanji characters - and you haven't memorized it through frequent contact then the chances are you might not get it right after all. There are far too many possibilities on how to pronounce it. Sometimes the variations are overwhelming. However, "It is true that, since some reading and characters are much more commonly used in names than others, it is usually possible to arrive at a likely reading when faced with a name written in characters..." (Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 5, entry by P. G. O'Neill, p. 324.)

2. "The uji or myōji [苗字 or 名字], our surname,... dating... only from medieval times. Most names of this class were originally nothing more than the names of localities in which the families bearing them resided, as Yama-moto, 'foot of the mountain;' Ta-naka, 'among the rice-fields;' Matsu-mura, 'pine-tree village.' Down to about 1870, surnames were borne only by persons of gentle birth..."

3. "The zokumyō [俗名] or tsūshō, literally, 'common name.' It corresponds closely to our Christian name. Very often such names end in tarō for an eldest son, in jirō for the second, in saburō for the third, and so on down to jūrō for a tenth son, as Gentarō, Tsunajirō, etc.; or else these distinctive determinations are used alone without any prefix. They mean respectively 'big male,' 'second male,' 'third male,' and so on. Other zokumyō, end in emon, suke, nojō, bei, - words formerly serving to designate certain official posts, but now quite obsolete in their original acceptation."

4. "The nanori [名乗り] or jitsumyō, that is, 'true name,' also corresponding to our Christian name.... Until recently the jitsumyō had a certain importance attached to it and a mystery enshrouding it. It is used only on solemn occasions, especially in combination with the kabane, as Fujiwara no Yoritsugu (no = 'of'). Since the revolution of 1868, there has been a tendency to let [the kabane] retreat into the background, to make [the uji] equivalent to the European surname, and to assimilate [the zokumyō and jitsumyō], both being employed indiscrimanately as equivalents of the European Christian name. If a man keeps [his zokumyō], he drops [his jitsumyō], and vice versa.

5. "The yōmyō [幼名], or 'infant name.' Formerly all boys had a temporary name of this sort, which was only dropped, and the jitsumyō assumed at the age of fifteen. Thus the child might have been Tarō or Kikunosuke, while the young man became Hajime or Tamotsu.

Chamberlain notes that the next list of name types, while still in use when he wrote the book, were not as important as the first group discussed above.

6. "The azana [字], traslated 'nickname,' for want of a better equivalent." Jim Breen gives as one of the definitions a "Chinese courtesy name..." Chamberlain notes that the azana is of a higher order than the Western nickname and basically is used respectfully.

This next entry is probably the most important one for our purposes.

7. "The gō [号]. 'Pseudonym' is the nearest English equivalent, but almost every Japanese of a literary or artistic bent has one. Indeed he may have several. Some of the Japanese names most familiar to the foreign ears are merely such pseudonyms assumed and dropped at will, for instance Hokusai (who had half-a-dozen others), Ōkyo, and Bakin. Authors and painters are in the habit of giving fanciful names to their residences, and then they themselves are called after their residences, as Bashō-an ('banana hermitage')...

8. "The haimyō or gagō [雅号]. These are but varieties of the gō , adopted by comic poets and by painters."

Number 9 is important too for our understanding of many Japanese actor prints.

9. The geimyō [芸名] is a stage name. For example, "...Ichikawa Danjūrō was not the real name, but only the hereditary 'artistic name,' of the most celebrated of modern Japanese actors. To his friends in private life he was Mr. Horikoshi Shū (Horikoji being the myōji, No. 2; Shū the jitsumyō, No. 4)."

10. "The okuri-na [諡], or posthumous honorific appellation of exalted personages. These are the names by which all of the Mikados are known to history, - names which they never bore during their lifetime. Jimmu Tennō and Jingō Kō gō are examples."

11. The hōmyo [法名] is a posthumous Buddhist name. We already have an entry on this form on our Hil thru Hor index/glossary page.

Chamberlain notes that the Japanese friend who helped him compile this list never considered mentioning the names for women. This Chamberlain adds as No. 12.

12. The yobi-na [呼び名] or women's names. [Most dictionaries I have consulted translate this as a 'given' or 'common' name and say nothing about gender.] "These are generally taken from some flower or other natural object, or else from some virtue, or from something associated with good luck, and are proceeded by..." the honorific 'O'.

According to Kawaoka Takeharu there was a practice in part of Hiroshima Prefecture until the middle of the Meiji period for a young man to change his name prior to marriage. "Boys got their names changed at the age of fifteen..." on the 15th day of the 1st month. Family members drank sacred rice wine on this occasion. |

||

|

|

||

|

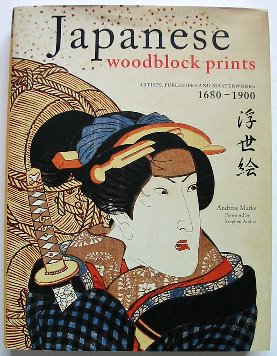

Japanese Woodblock Prints: Artists, Publishers and Masterworks 1680-1900 |

|

This volume by Andreas Marks is a valuable addition to the library of any serious collector of Japanese woodblock prints. Or, for that matter, for any scholar or dilettante interested in ukiyo-e in general. The one thing which we find the most interesting is the section on 49 different publishers. We know of no other volume in English with so much information on this important area of research. Stephen Addis in the foreword to this book wrote that Marks "...provides a much-needed recognition of the vital role played by publishers." We second that opinion completely.

The first half of the book is devoted to 50 individual artists and the second half to individual publishers. Both are in chronological order. |

|

Jigoku |

地獄

じごく |

The Japanese name for hell. Separately the kanji characters mean earth or ground 地 plus prison 獄. Jigoku was also the name given to the lowest class of unlicensed prostitutes - or they were called jigoku onna, hell women.

|

|

In Drums of the Waves of Horikawa, a play by Chikamatsu, the drummer Gan'emon chants:

|

||

|

|

||

|

Jigoku Dayū |

地獄太夫

じごくだゆう |

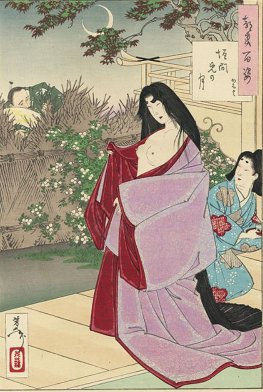

The Hell Courtesan, a possibly fictitious figure whose encounters with the Zen monk Ikkyū became the subject of novels, plays and fine art pieces. 1

The image to the left is by Kyōsai and dates from 1874. We found it at Pinterest. Timothy Clark in the Demon of Painting: The Art of Kawanabe Kyōsai, p. 103, said: "The courtesan seated on a priest's chair, seems to be impersonating Daruma's saffron monk's robes with the striking red gauze cloak worn over her costume. This has fallen open at the leg to show the end of her sash decorated with scowling Emma, King of Hell - so revealing her true identity as Jigoku Dayu. the Hell Courtesan. Letting fall her ceremonial priest's fly-whisk (hossu), she and her kamuro child attendant kneeling on the floor have both dozed off and see in their dreams the vision of Bacchanalia. ¶ With headstones knocked over in all directions, the skeletons party for all they are worth - drinking, dancing, playing music, playing go and even helping one another up out of the grave. None of this seems to bother the sleeping courtesan, but then we notice the skulls carved on the end of her tortoiseshell hairpins and realise that for her this must be quite a normal vision." |

|

Jimbaori (or jinbaori) |

陣羽織

じんばおり |

A formal surcoat worn over armor either for ceremonial purposes or else on the battlefield. Originally designed for more practical use as protection against foul weather and the cold, but in time these jackets became elaborate status symbols often decorated with a family crest or mon with strong design which could be seen clearly at some distance.

The image to the left is the backside of an Edo period jinbaori from the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. We found it at Pinterest. |

|

Jingasa |

陣笠

じんがさ |

An 1888 pocket dictionary defines the jingasa as "A kind of large hard hat worn by soldiers, or firemen."

In volume 3 of the Russo-Japanese War series from 1905 it say on page 909: "The introduction of fire-arms brought about great changes in the defensive armour of the warriors, iron plates taking the place of leather. An iron plate helmet, painted with lacquer, and called Jingasa, came into frequent use..."

Stephen Turnbull in his The Most Daring Raid of the Samurai (p. 25) notes: "Tools would have been wielded by non-combatant laborers who, unlikely to have been wearing armor, may well have been issued with a jingasa." Their coats would bear the crest or mon of their master.

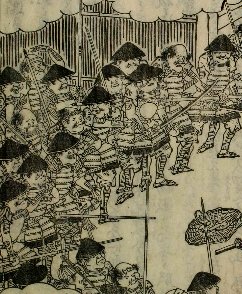

Foot soldiers wearing their jingasa.

The Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Land Warfare: An Illustrated World View by Byron Farwell gives a more expansive description: "A low-crowned Japanese war helmet of wood or metal, padded on the inside. Padded flaps hang down at the sides."

The Hutchinson Dictionary of Ancient and Medieval Warfare (p. 168) adds that this "...conical hat, usually made of iron in single or multiple plates, but sometimes of lacquered wood, worn in battle by the ashigaru from the Muromachi period (1333-1568) onwards. In later periods it was worn in parades."

The image to the left was posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Samuraiantiqueworld. |

|

Jinmaku |

陣幕

じんまく |

A military curtain - These can be described as either camp or war curtains. "In the feudal period Japanese generals surrounded their encampment with cloth curtains. These were usually sewn together horizontally and varied in colour to distinguish the individual generals." Quoted from footnote 16 in 'Mitate kokkei Chūshingura. Hiroshige's humorous parodies of the Loyal Retainers' by Pierre Wijermans and Henk Herwig in Andon 84, November 2008, p. 72. |

|

Jinmenju |

人面樹 じんめんじゅ |

The human-faced tree: According to Yokai Attack: The Japanese Monster Survival Guide by Hiroko Yoda and Matt Alt (published by Kodansha, 2008 pp. 114-117) this tree grows to a height of 6 to 35 feet. It is extremely rare and grows mainly in mountainous valleys. Its fruit takes the form of human heads which can speak either singly or as a chorus. If they aren't talking they giggle. The fruit is said to have a somewhat citric, tangy flavor, but as the authors of Yokai Attack muse "...we wonder what kind of person would bite into the head of a tiny human..." They offer no threat and actually are rather gentle. In fact, they are so easily amused that sometimes they laugh themselves right off the tree. ¶ Their lore may have reached Japan from China having originated in India and Persia. First mentioned in Japanese literature in 1712 in the Wakan Sansaizue (和漢三才図会). It may even be related to the Waqwaq tree of Arabian Nights fame where the fruit were said to bear a great resemblance to human faces. |

|

On 12/21/08 our great contributor 英渓 (Eikei) sent us an important passage from "Journey to the West" translated by Anthony C. Yu (University of Chicago Press, 1977, vol. 1, p. 264). It takes place on the Mountain of Longevity where there is the Taoist Temple of Five Villages which is the abode of an immortal. Unique to this temple is an extraordinary tree [and here is where it relates to the Japanese jimmenju]: "This treasure was called grass of the reverted cinnabar, or the ginseng fruit. It took three thousand years for the plant to bloom, another three thousand years to bear fruit, and still another three thousand years before they ripened. All in all, it would be nearly ten thousand years before they could be eaten, and even after such a long time, there would be only thirty such fruits. The shape of the fruit was exactly that of a newborn infant not yet three days old, complete with the four limbs and the fives senses,. If a man had the good fortune of even smelling the fruit, he would live for three hundred and sixty years; if he ate one, he would reach his forty-seven thousandth year."

If you are unfamiliar with "Journey to the West" you may know it through its shorter version, Monkey, translated by Arthur Waley. Both are based on the sixteenth century Hsi-yu Chi (西遊記) by Wu Ch'êng-ên (吳承恩). |

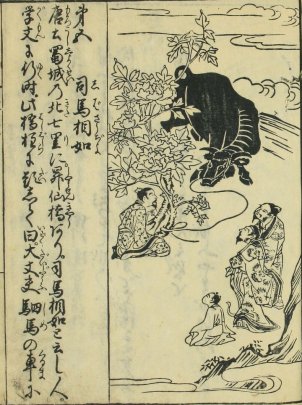

||

|

|

||

|

Jiraiya |

児雷也

じらいや |

"The image of a man with a toad, the man being without the usual leafy collar of the sennin, may be an illustration for the novel of Santō Kyōden (1731-1816) [sic] whereof Jiraya [sic] is the hero. The young man, though of noble birth, became a robber through lack of funds. One night having found shelter in the house of an old woman, he tried to rob her. But he was overcome by the woman who had changed into an old man and turned out to be a powerful wizard, the Spirit of the Toad. His victor apparently seeing some good in the robber treated him kindly and instructed him in his own art, pledging Jiraya at the same time henceforward to be a protector of the poor and oppressed. So instead of a robber our hero became indeed a hero. But there was a sorcerer of evil repute, who was still stronger than he. Now one day Jiraya met a pretty girl and fell in love with her. They married and as a dowry she brought him a very valuable and useful gift for she was a pupil of the Spirit of the Snail. Together these two performed many good deeds and overcame and killed Orochimaru, Python-fellow, the son of the Spirit of the Snake. One day as the young couple had taken lodgings in a temple, the Spirit of the Snake penetrated there and spat on Jiraya, poisoning him. In all haste the priest of the temple sent a messenger to India on the back of a tengu... to fetch an antidote. The messenger was back in time to save Jiraya's life and now in league with the Spirit of the Snail, Jiraya killed the Spirit of the Snake." (Quote from: The Animal in Far Eastern Art... by T. Volker, p. 169)

"Possibly this novel of Kyōden's was inspired by the popular belief incorporated into the triad called: 'San sukumi', three that fascinate each other: the toad, the snake and the snail. The snake eats the toad, the toad eats the snail but the slime of the snail (the same is said of human spittle), means death to the snake." (Ibid.)

*Santō Kyōden's (山東京伝) actual dates are 1761-1831. |

|

Jiraiya Goketsu Dan |

児雷也豪傑譚 じらいやごうけつだん |

"Conversations about the Hero Jiraiya" 1 |

|

Jisei |

辞世

じせい |

Death poem(s): "In Japan, as elsewhere in the world, it has become customary to write a will in preparation for one's death. But Japanese culture is probably the only one in the world in which a 'farewell poem to life' (jisei) took root and became widespread."

Quote from: Japanese Death Poems: Written by Zen Monks and Haiku Poets on the Verge of Death, compiled with an introduction and commentary by Yoel Hoffmann, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1986, p. 27.

"Poems written just before death appear in the most ancient Japanese sources, including the Kojiki, the Man'yoshu, and the Kokinshu."

Ibid., p. 44.

"At the moment of death, say followers of the Jodo sects of Buddhism, the dying person is greeted either by Amida, the Buddha of Everlasting Light, or by Kannon, the Bodhisattva of Compassion and Love. Anyone who call the name of Buddha before dying is reborn in the Pure Land in the West."

Ibid., p. 66.

There is a shini-e or memorial print by Kunichika dedicated to his master Kunisada. It shows several poems by devoted pupils. However, "The poem on the far left is Kunisada's death verse (jisei), signed 'The Old Man Toyokuni, aged seventy-nine,' in which the artist expresses his faith in Amida (Mida), the lord of the Western Paradise..."

Quote from: Kunisada's World, by Sebastian Izzard, Japan Society, Inc., 1993, cat. #100, p. 189. |

| On 9/11/08 we added the image of the cover of the book devoted to this subject compiled by Yoel Hoffmann. | ||

|

|

||

|

Jitsubushi |

地潰し

じつぶし |

A background printed in a single color. This may involve layering of different colors or of the same color, but the end product leaves a relatively flat printed ground.

The image to the left is a detail from a Yoshikawa Kanpō (1894-1979: 吉川観方) print. |

|

Jitte |

十手 じって |

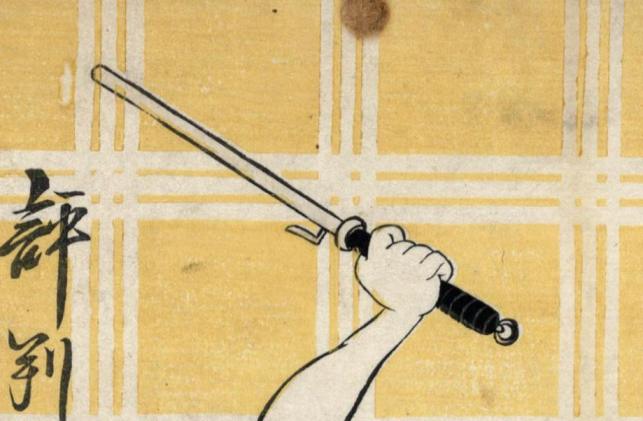

An archaic term for a short metal truncheon used by police to nab criminals. The image shown below is from an 1822 Hokushū triptych."The iron [jitte]

|

|

"The iron [jitte] were sometimes coated with ginnagashi, an amalgam of silver and mercury that gives a shiny, silvery effect when polished. Because this coating came off easily, some had silver plating instead, which is why jutte were sometimes called ginbo (銀棒, "silver sticks"). The jutte's hilt (nigiri-e) was usually no different from the rest of the metal rod, but it is possible to find models with the handle wrapped in leather, ray skin, or rattan, or fitted with brass collars. Very special ones had hilts constructed like those on a sword. Rare models were even provided with a scabbard. ¶ The jutte is often associated with the Edo-period policeman, as it was a symbol of his authority as well as being a useful weapon for apprehending criminals. Depending on the era, the rank of the user, and the level of danger he might encounter, the length of the jutte varied considerably. In addition to being a symbol of the Edo-period policeman, the jutte was often carried by troublemakers as well. ¶ There were a huge variety of jutte models, and one source claims that approximately two hundred kinds were used in the Edo period. The length ranged from The length ranged from 25-28 centimetres for short ones, and from 55-64 centimetres for long ones. Before the Edo period, however, long models measured between 70 to 90 centimeters. The short variety was nicknamed futokorojitte (懐中十手), koshijitte (腰十手), and koshizashi (腰指) because it could easily be concealed in the futokoro (kimono fold) or inserted into the obi behind one's back to allow it to be drawn quickly. Some longer jutte that were more suited for serious fighting with armed and dangerous criminals or ronin (masterless samurai) were called sentōyō-jitte (戦闘用十手, "fighting jitte/jutte). Ideally the jutte had to provide sufficient protection, and when held in a reverse grip with the metal rod against the forearm, the tip had to extend at least to the elbow. Around Around the Kyōhō era (1716-36), regulations were laid down to ensure that official police jutte conformed to a standard length. At one time the standardized jutte, or jōsunjitte (定寸十手), was approximately 36 centimeters. Both standard-issue jutte and private models existed, since, as a rule, the Edo-period policeman was issued with a service jutte when going out on patrol or going to arrest a criminal, but he had to return it to his station afterwards, since the jutte could only be used under the supervision of a ranking officer and could not be taken home. Thus, many lower-ranking policemen made or ordered private jutte and carried these, even when not. The jutte used by officers was fitted with a cord and tassel of different colors, depending on rank. Lower-ranking policemen and their assistants were not allowed to use a jutte with a tassel. This tassel-less jutte is called a bōzujitte (坊主十手, literally, "shaven jitte/jutte)... " Quoted from: Classical Weaponry of Japan: Special Weapons and Tactics of the Martial Arts by Serge Mol, pp. 77-78. |

||

|

|

||

|

Jizai kagi |

自在鉤

じざいかぎ |

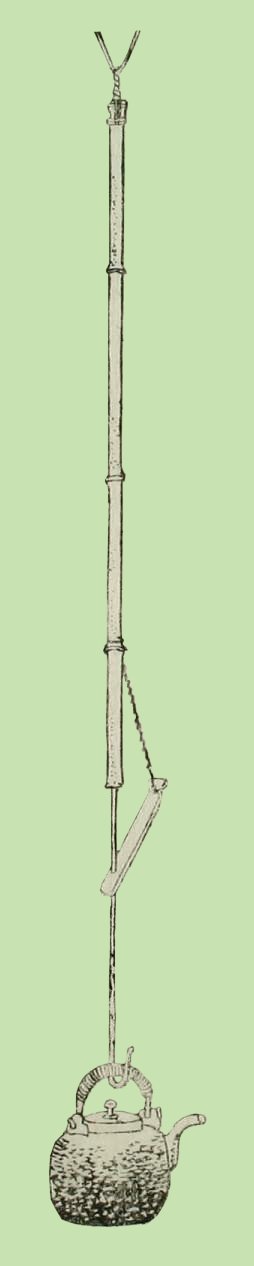

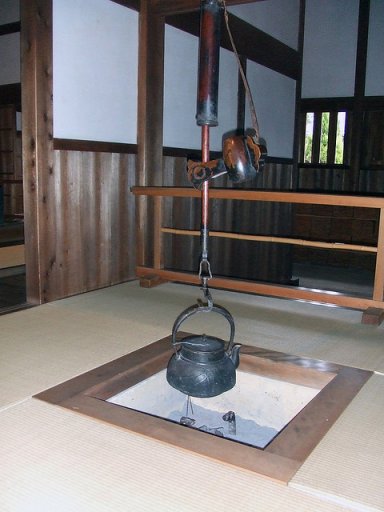

Pot hook: An height adjustable mechanism for hanging a pot over a fire traditionally found in most Japanese homes from those of peasants on up. There are two different kanji characters used for kagi. One means 'hook' [鉤] and the other means 'hanger'.

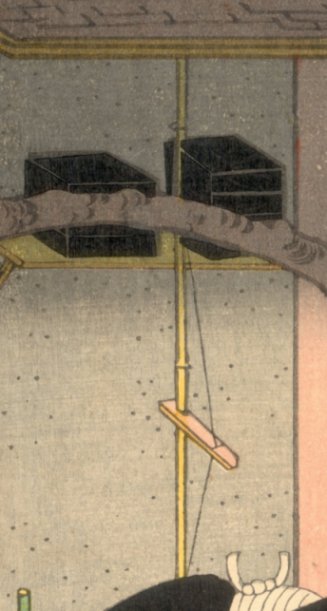

Some of you may wonder why I add such esoteric subjects as the jizai kagi. Well, I'll tell you. In this case the jizai kagi appears in two separate woodblock printings I know. The large one to the left is from an ehon illustrated by Sadahide. The two examples given above are from the left panel of a Kunitsuru diptych. If an image appears and if anyone out there was wondering what it might represent or be then that is the reason we are trying to cover these elements in such an encyclopedic way. You may not agree on this approach, but basically if it is out there I want to know what it is and why. |

|

"Kettle Hangers: A feature of most irori (sunken hearths) is the iron pot or kettle full of water that is kept over the coals. Although a pot or kettle can be placed on an iron tripod or four-legged stand within the hearth, quite often it is hung over the irori on a hook affixed to a metal chain or a thick rice straw rope. The chain or rope, in turn, is suspended from the building structure either by being directly attached to a beam or other structural member or, more often, by being connected to a vertical bamboo or wood pole Which is joined to the structure. In some cases, the hook may be connected directly to a vertical or wood or bamboo pole rather than a chain. ¶ An ingenious contraption, the jizai (“at one's will”) or jizaikagi (kagi means “hook”) is used to adjust the height of the kettle. There are many variations of the jizai, but the concept behind it is the same for all —to use the weight of the kettle and the friction of one component (generally a wooden paddle attached with a metal rod) against another (the vertical bamboo or wood pole) to hold the kettle in place. In simple minkaI, jjzai are equally simple, whereas in upper-class houses, jizai can be quite elaborate, incorporating carved wooden fish or other symbolic forms of symbolic metalwork." Quoted from: Traditional Japanese Architecture: An Exploration of Elements and Forms by Mira Locher, 2013.

This image was posted by Andurinha at Flickr. |

||

|

|

||

|

Jizō |

地蔵

じぞう |

Patron saint of children and travelers: Jizō is the Japanese name for the bodhisattva Ksitigarbha. There are ten variant manifestations of Jizō, perhaps more. One is to oversee the safety of souls who have died until the coming of the next Buddha. "...there is also a Jizo who is especially named Ko-sodate-Jizo [子育て地蔵] (children raising Jizo). It is said that when children die, they go to the banks of the Sanzu River, but as they play there, devils come to disturb them. Then Jizo arrives to protect these children."

This is an interesting contrast to the Christian belief that everyone is born into original sin and has to be baptized for the soul to be properly saved.

The image to the left is from a tattoo on the back of someone who wishes to remain absolutely anonymous. I want to thank the Jizō wearer for having submitted this photo to this site. We needed a good example for these pages. Thanks Anonymous! (Note the children gathered around the feet of this bodhisattva frolicking within the petals of the lotus flower.) |

|

Some people believe that the oracle of Delphi made her pronouncements after inhaling fumes rising from a fissure in the ground. Perhaps she did. Over the years I have visited both Yellowstone and Mt. Lassen. Both are incredibly active geological sites and both have pools of superheated water some of which are predominantly sulphuric. Both have bubbling mudpots and hissing fumeroles. Both have suffered cataclysmic/global altering explosions. Well, the area around Mt. Osore (恐山 or おそれざん) where the statue of Jizō shown above is found has many great similarities to our two national parks. Located at the northernmost part of Honshū, not far from the strait which separates it from Hokkaidō the traditional home of the Ainu. This region stinks of sulphur. It is seismically active: today is 9/12/08 and yesterday there was a 6.9 quake not far away. Of course, this area differs in certain ways from its sister regions in Wyoming and California, but overall the similarities are greater than the differences. ¶ Traditionally the Ainu viewed the Mt. Osore area as a spiritual center. (New Agers still make pilgrimages to Mt. Shasta which is a near neighbor to Lassen.) The greenish-yellow lake, Usoriyama, shows almost no signs of life. Almost nothing can live there. In fact, it only supports one hardy, extremely hardy, species of fish, the ugei or big-scaled redfin. There are almost no birds in this part of the Shimokita Peninsula (下北半島) - Aomori Prefecture (青森県). Rhododendrons grow there, but they do well in highly acidic soils. However, most plants if they did take seed would wilt if they did survive germination. Loud black crows flock here and that alone would give the sense of pending doom and darkness considering there are rocky barren stretches everywhere. ¶ After the arrival of Buddhism at Mt. Osore the same kind of syncretism took place as it did everywhere else in Japan. (Remember that until they were forced apart in the 19th century Buddhist Temples and Shinto shrines were often indiscernible.) Osorezan can be translated as the Mountain of Dread and the Buddhist adapted to this. By the 9th century they had built a temple there, Entsūji (円通寺). There is also the Bodaiji Temple (菩提寺?) which is close to the Lake of Blood, the Mountain of Swords, and a dry river bed which many believed was the mythical Sai no Kawara (西の河原) or River Bed of Souls over which the living cross to the land of the dead. ¶ The souls of children who die young, before their parents populate this area. The living make pilgrimages here in efforts to assuage the suffering of these souls and obviously to mitigate that of their own. They leave toys and candy treats as offerings. This is why Jizō plays such a prominent role. He is traditionally the greatest protector of these youthful' souls. ¶ Working alongside the Jizōs are the itako (いたこ) or blind - generally unmarried female - shamans who are able to contact the souls of the dead. For centuries parents would give over young daughters for itako training, but since the end of World War II child protection laws has caused their numbers to dwindle. Primarily, itako exercise kuchiyose (口寄せ): they summon the spirits of the dead who communicate with the living using the itako as a mouthpiece." (Shinto in History, by John Breen and Mark Teeuwen, p. 190) For the Jizō holiday in August itako gather at Osorezan and perform their craft for three days. "It appears that throughout the history of their profession, itako have performed, in particular, memorial rites for the souls of aborted foetuses, mizuko kuyō, and these rites also aim at helping mothers come to terms with their feelings of guilt, their distress, and their anxieties." (Ibid., p. 191)

"The scene is reminiscent of a Hitchcock movie as clouds of steam rise from hissing vents in the ground and flocks of ravens swarm over shrines dotted across the barren slopes. The shrines are surrounded with garishly coloured toys and children's whirligigs spin in the breeze. Paths lead down to the leaden waters of the lake that has formed in the caldera. The small statues of Jizō, the Buddhist deity in charge of the spirits of departed children, are covered with bibs and sweets. ¶ Whatever your beliefs, it would be hard to deny that there is a strong, sinister feeling here of otherworldly power." (Japan entry by Robert Strauss, Lonely Planet Publications, 1991, pp. 274-5)

The photo of the statue of Jizō above was placed in the public domain by Jpatokal. For this we are extremely grateful. The original is posted at http://commons.wikimedia.org/.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Jizuri |

自摺

じずり |

Self-printed

To the left is the seal from a Hiroshi Yoshida print. |

|

Jō |

上 じょう |

The kanji character used to mark the first volume in a series.

The images to the left are from the Lyon Collection. Click on them to go to see more information. |

|

Jō and Uba |

尉 and 姥 じょう and うば |

These two are an old and loving couple who are representatives of marital bliss. Jō means 'old man' and Uba 'old woman.' Their physical presence came to be represented by two pine trees. In one account these trees are growing next to each other and are entwined. Another version puts them at some great distance from each other. The spirits of both of these people are said to possess each tree. And it is said that on dark, misty, moonlit nights the souls of Jō and Uba reappear, he with a rake and she with a broom. The rake may symbolize the gathering of a those things which make for a happy future while the broom may represent the dispersal of evil. After living in marital bliss for ages and ages they are said to have died together on the same day and at the same hour. When they reappear they are said to go to the beach at Takasago to gather pine needles.

They are often seen accompanied by a tortoise and crane, both symbols of longevity. "Their statuettes are given as wedding presents and on this occasion the Nô-play, depicting their lives was often played. The Takasago-song from the play is even nowadays sung at weddings." Quoted from: The Animal in Far Eastern Art... by T. Volker, 1950, p. 154.

The image to the left was altered by my friend Evan Black from an original photo by Jnn at commons.wikimedia. |

|

Jōe |

浄衣 じょうえ |

Literally a pure garment - A white robe or costume. Brian Bocking says of this piece of clothing: "A white silk version of the kariginu; a Heian-style garment used by priests and others in religious ceremonies."

The picture shown above was posted at Flickr by Kumar nav. |

|

Jōhari no kagami |

浄玻璃の鏡 or 浄頗梨鏡

じょうはりのかがみ

|

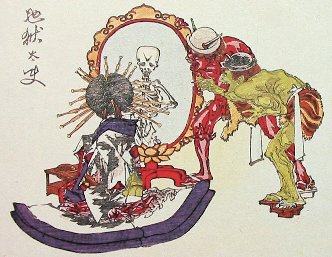

Jōhari no kagami (Pristine Crystal Mirror)

The karmic mirror in hell which will reflect all of the bad things a person has done after the age of 7.

"Reflected therein are 'each act of good and evil, every karma-producing act performed during that person’s previous life.' The text describes the vision as “akin to actually encountering people and seeing their faces, eyes, and ears.' The proceedings in Enma’s court do not anticipate vehement denial of good deeds, but rather function to expose evil behavior easily concealed in life. In the face of omniscient witnesses and irrefutable corroboration, sinners cannot repudiate or redefine the facts." There is no use trying to fudge the truth because each soul has a 'together-born-deity' which will testify as to the actual facts right after the deceased has testified. Source and quote from: 'The Inflatable, Collapsible Kingdom of Retribution: A Primer on Japanese Hell Imagery and Imagination' by Caroline Hirasawa, pp. 15-16. Published in the Monumenta Nipponica, 63:1.

"In the many Japanese hell paintings incorporating images of such mirrors, the crime most commonly recorded is killing. Aside from cardinal sins such as murdering monks or setting fire to temple property, the mirrors reflect killing associated with vocational and culinary customs such as the butchering of animals, fishing, and hunting game. Animals gather around some mirrors, accusatorily facing their slaughterers. Other mirrors depict warriors engaged in battle. Such iconography prompted consciousness of the retribution awaiting those engaged in certain professions and primed them to consider their options for salvation." (Ibid., p. 16)

In a footnote Hiraswa writes: "Lest the mirror, banner stanchions, and witnesses were not enough to ensure justice, a scale belonging to the fourth king weighs sinners against their sins." (Ibid.)

|

|

Jōi |

攘夷 じょうい |

Expel the Barbarians - There were several efforts among the Japanese to rid themselves of foreign influences during the Edo period. In 1825 the bakufu promulgated an act to renew these efforts: "[the foreign ships] have become steadily more unruly, and moreover, seem to be propagating their wicked religion among our people. This situation plainly cannot be left to itself. ¶ All Southern Barbarians and Westerners... worship Christianity, that wicked cult prohibited in our land. Henceforth, whenever a foreign ship is sighted approaching any point on our coast, all persons on hand should fire on and drive it off." Quoted from: International Relations and Identity: A Dialogical Approach by Xavier Guillaume, p. 79.

Xavier Guillaume also says: "It is ironic that a term aiming at enforcing jōi was inspired by 'Western learning' (rangaku)." Ibid., p. 80. |

|

Jōkamachi |

城下町

じょうかまち |

Castle town: Traditionally places like Fuchū, Hikone, Hirosaki, Iida, Kanazawa, Matsue, Matsumoto, Nagoya, Okazaki, Takashima and Toda, et al. were laid out in a hierarchical pattern with the castle keep or tenshukaku (天守閣) at the center. Early on Edo, another jōkamachi, did not follow this pattern. In fact, originally it was just the opposite with the most important vassals located some distance from the center, i.e., the castle. Here is was meant more as a defensive positioning meant to protect the Kantō plain.

Above is Matsumoto castle posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Σ64.

In The Economic Emergence of Modern Japan E. Sydney Crawcour said on p. 18: "In each domain, the castle town acted as the commercial as well as the administrative center and performed at the domain level the functions analogous to those that Osaka and Edo performed at the national level. Licensed or 'privileged' merchants acted as agents for the collection, distribution, import, and export of goods from the domain, financed and often managed domain enterprises, and backed and managed domain note issues (hansatsu)."

To the left is a photo of Kanazawa castle posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Fg2. "Kanazawa is considered to be one of the few successful cases in which a castle town was developed into a large local city and yet has maintained it original historical character." Unlike most other major Japanese cities Kanazawa had survived World War II relatively unscathed by comparison. While this was considered to be a handicap preventing it recreation as a modern city in time it came to be viewed as an asset since so much cultural heritage had been bombed into oblivion elsewhere. (Source and quote from: International Urban Planning Settings: Lessons of Success, Volume 12, p. 312) Kanazawa gained its wealth from being at the center of the largest rice growing region of Japan. It also had the largest population of any jōkamachi during the Edo period and was said to have 120,000 inhabitants at the beginning of the Meiji Restoration. By 2000 the population was only 100,000 in the older, preserved parts of the city, but the general area hold more than 4 times that number. (Ibid., p. 314) |

|

In the 16th and 17th centuries castle towns were being developed along militaristic lines. "Most of Japan's modern cities began as towns built around a daimyo's castle. A castle town or jokamachi symbol of the regime's military and political authority was the main feature in the development of the cities in Japan during this period. The castle was the centre of each domain's defence and government. The town that grew around them became the focus of dominant commerce activities in developing the area. There was rapid growth of cities in this era due to the growth in trade. There were about 100 cities built over a period of 50 years." ¶ "The Castle Town of Kanazawa in Ishikawa Prefecture is one of the best-known surviving examples of an old castle town. Maeda's family, the wealthiest daimyo in the land during that era owned a castle that was built on the confluence of two rivers. The town was laid out around the Saikawa and Asanogawa rivers." (Quoted from: An Introduction to Japanese City Planning by Chin Siong Ho, p. 29)

Jōkamachi literally meant 'town below the castle'.

During the Tokugawa period samurai gravitated to these castle towns and operated as menials or bureaucrats, but not very good ones. This kept them dependent on the local daimyos and out of trouble.

Carl Mosk in his Japanese Industrial History: Technology, Urbanization, and Economic Growth (p. 38) gives a very succinct and precise description of the jōkamachi: "The most important facet of the building boom outside of the core was the proliferation of castle towns, jōkamachi, that served as the residential headquarters for daimyō and their retainers. The number of such castle towns fluctuated somewhat during the early modern period, since the number of fiefs changed from time to time, varying between about 240 and 295 in number. In many cases, these castle towns were erected upon a pre-Tokugawa foundation. Originally, many had been staked out as market towns, their sites reflecting natural advantages as transportation nodes. Under the federal structure that developed with bakufu rule, castle towns took on a rich combination of administrative and commercial functions. None were formally called cities - the Chinese character for city, shi, was not applied to any conurbations until the 1880s - nor were they under some form of municipal government rule as were some cities in the West at this time. Indeed, under the standard administrative model of the bakuhan system, a castle town was administered by one (or several) machi bugyō, municipal administrators appointed by the ruler of the domain governing the castle town. In practice, neighborhood (chō) associations played an active role in managing urban affairs, organizing religious events, and assembling and recruiting fire brigades to fight conflagrations. In sum, the construction of castle towns created a network of regional administrative cum commercial nodes connected by roads, rivers, canals, and seacoast, so that core was linked to periphery, and points in the periphery were linked to one another." ¶ The construction of castle towns and roads spurred a 'massive building boom'. Relocating samurai retainers to the jōkamachi put physical distance between them and rural peasants and farmers which brought an end to "protracted squabbling over water rights, and the arbitrary diversion of water brought from rivers along irrigation canals by aggressive villagers riding roughshod over their neighboring villages." Water was all important - especially for the production of rice which was the measure of one's wealth. (Ibid. p. 14) [The part about relocating samurai to the castle towns does not always jibe with what we have read elsewhere, but tends to be the general consensus among historians and scholars.]

"In 1950, about 50% of all Japanese cities (Hokkaidō excluded) were former castle towns." (Quoted from: Modern Japanese Society, Part 5, Volume 9, p. 282)

"Throughout Japan, though in differing degree in different areas, the civil wars of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries had begun the process of detaching samurai from the land. The need to have an army more or less on call had led the daimyo to insist that their followers live round a central stronghold. This samurai community became in many cases the nucleus of a castle town. When peace was restored under the Tokugawa, the practice continued, partly because of its administrative convenience, partly because it strengthened a lord's authority over his men. As a result the majority of samurai became townsmen, resident in or around the castle, except when they were sent to serve in Edo... or were employed as officials in a rural area." (Quoted from: The Meiji Restoration by William Beasley, p. 21)

"During the years of Nobunaga and Hideyoshi, small castle towns sprang up like toadstools, along with a variety of port and highway towns - some ninety new towns appearing between 1572 and 1590 alone - and after 1600 most of them continued to grow. (Quoted from: Early Modern Japan by Conrad Totman, p. 63)

"At the beginning of the 16th century most of the major cities of modern Japan were completely undeveloped, but during the three centuries from 1570 to 1850, the castle town, or jōkamachi, assumed an importance out of all proportion to other types of urban communities." (Quoted from: Max Weber in Asian Studies by Andreas Buss, p. 91)

"An important change took place in rural life as the new barons established themselves in their fortified castles. They grew more and more averse to letting their more important vassals and followers reside on their own estates, where they might plot mischief. Consequently they obliged such important people to reside near the castle, leaving their estates to be managed by stewards. This action resulted in the growth of castle towns (jōka-machi) and the separation of the warrior from the farmer. Hitherto there had been no clear distinction between the two classes, since a warrior might be a farmer living on is own land. But now the professional soldier lived an urban life, and rural society developed on new lines, with an elaborate organization of village life and marked social distinctions between the headman and the plain cultivator." (Qutoed from: A History of Japan, 1334-1615 by George Sansom, p. 256)

"Within any castle town, some wards were made up almost entirely of a small group of elite merchants who supplied certain crucial military or prized luxury goods to the daimyo, items such as munitions or arms, rice in bulk shipments, silks and other quality clothing materials, or cakes and saké. The daimyo would grant charters to these men, vouching that he would buy their products and thus coining the generic term, gōyō shōnin, purveyors to the lord, that defined this distinctive group. In addition to the charters, the lord often bestowed on these merchants tax exemptions and residential housing plots within the better wards, generally known as the hommachi, that were close to the castle and among the first laid out, locations that had the additional advantage of being near the wealthier samurai customers. ¶ Also given preferential treatment were the forwarding agents, the men who procured packhorses, arranged coolie labor, and otherwise managed the details of the daimyo's export trade. Typically they received residential plots in the center of the commercial section, an area that then became known as Temmamachi, literally the post horse ward. Similarly, each daimyo required the services of certain kinds of artisans - swordsmiths, armorers, carpenters, stone cutters, plasterers, and tatami makers - to entice them to his domain he would offer guarantees of employment, tax exemptions, and housing that was conveniently situated close to the castle." People of similar skills would be clustered together and often those areas would take on the name of their trades and some of these names continue in use today. (Source and quote from: The Japanese Economy in the Tokugawa Era, 1600-1868, p. 142-3) |

||

|

|

||

|

Jōkyō |

貞享

じょうきょう |

The reign era from 1684-88. [This] "...is a brief [period] but marks the magnificent end of the first phase of Japan's plebeian renaissance. In literature, Saikaku and Basho produced the major works of their middle period, and in ukiyo-e, Moronobu, Sugimura and Hambei completed their impressive series of illustrated books and albums which portray so vividly the life of the times." Quoted from: "Historical Eras in Ukiyo-e" by Richard Lane in Ukiyo-e Studies and Pleasures, Society for Japanese Arts and Crafts, the Hague, 1978, p. 28.

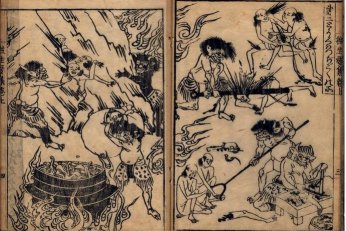

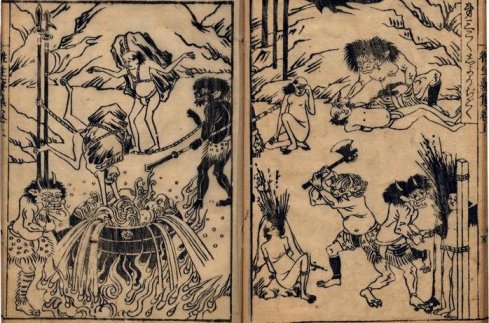

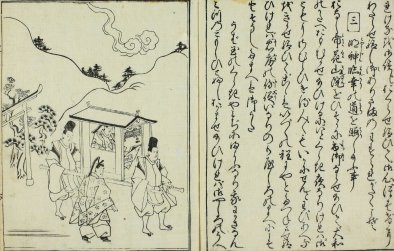

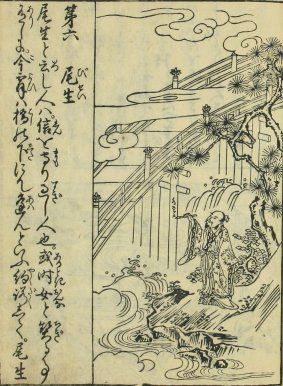

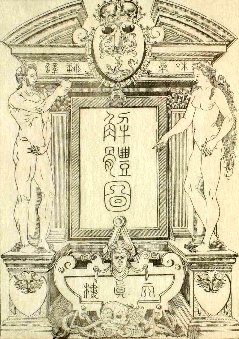

The image to the left and immediately above are from a 1687 edition of the Yoshino shu monogatari. The two below are from a 1688 edition of the Ehon Hokan. We are showing these book illustration details are representations of the typical carving skills of this period.

|

|

Jomon |

縄文 じょうもん |

An early cultural period in Japan named after a type of pottery with a corded pattern. The literal translation of the characters mean straw-rope or cord decoration. Some scholars date its earliest proto-period to 10,000 B.C. or before. Others give a much later date. All agree that this period ended in ca. 300 B.C. The example shown below comes from the Tokyo National Museum.

|

|

Jōō |

承応

じょうおう |

The reign era from 1652-55. This period "saw the banning of 'Young Men's Kabuki' and increasing emphasis on art and skill in Kabuki rather than sex appeal. The genre/ukiyo-e style of painting was at an early peak of popularity... and appears more and more in the book illustration of the period." Quoted from: "Historical Eras in Ukiyo-e" by Richard Lane in Ukiyo-e Studies and Pleasures, Society for Japanese Arts and Crafts, the Hague, 1978, p. 28.

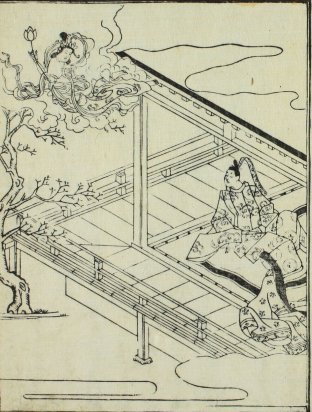

The image to the left is from a 1654 edition of the Tale of Genji. It shows more refined hands in designing and cutting this block than those produced in the previous decades. |

|

Jūnihitoe |

十二単 or 十二単衣

じゅうにひとえ |

The ""twelve-layered" formal robe worn by high ranking women of the Heian court. Also referred to as a karaginumo (唐衣裳).

"Probably the most famous Japanese example of this kind of 'wrapping' is the junihitoe of the court ladies of the Heian period, whose twelve layers of kimono were chosen to create an aesthetically pleasing combination of colour contrasts. Such sumptuous attire represents the ultimate expression of the way clothes and their colours were indications of social status..., a phenomenon certainly not peculiar to Japan. Nowadays, these garments are only to be seen at Imperial weddings when they also indicate the extreme formality of the occasion, as do fewer layers for more ordinary mortals. A regular bride in modern Japan often wears at least three layers of garments, the outer one being the most luxurious, but with the inner layers visible at its peripheries." Quoted from: Unwrapping Japan: Society and Culture in Anthropological Perspective, in an essay by Joy Hendry, p. 17.

In early May there is a purification ceremony for the head priestess, the saiō, of the Shinto shrines at Shimagamo and Kamigamo. She is represented by a stand in, a saiō-dai. "Since style and elegance continue to charm modern-day Japanese just as they did their ancestors, it is likely that people are more interested in seeing the attire, makeup, and stately demeanor of the saio-dai and her attendants than the extremely short purification ritual itself. The saio-dai wears a twelve-layered kimono called 'juni hitoe' covered with a white outer robe, the omigoromo. Both are associated with Heian period courtly life as famously described by Murasaki Shikibu in the Tale of Genji and as depicted in the scroll paintings (e makimono) of that era. She carries a large tan (hiōgi) wrapped with many multicolored strands of braided silk. Most strikingly, her gold-plated headpiece (saishi) is said to evoke the crowns of early shamanic rulers both on the continent and in Japan: it is an upright tree whose branches are bedecked with silver plum blossoms. The tree is anchored by an upper half-disc of sun, which in turn is supported by a lower half-disc of moon at the bottom of the saishi just above her forehead. This design recalls the himorogi, or original sacred place of early kami worship (as well as the vertical universe of Siberian shamanism), while the sun and moon symbols speak of Taoism and yin-yang balances thought integral to the proper functioning of cosmic and human worlds." Quoted from: Enduring Identities: The Guise of Shinto in Contemporary Japan by John K. Nelson, p. 207.

The image to the left was posted at Flickr by Nemo's great uncle. |

|

There was a theatrical piece, The Twelve-fold Kimono: Komachi and the Cherry Tree (Jūnihitoe Komachi Zakura) composed by Sakurada Jokō I (1734-1806). "Because no script of Twelve-fold Kimono exists, scholars have had to piece together whatever they can of the full play,,, Producing Twelve-fold Kimono as the season opener meant that it was the company's 'face-showing' (kaomise) performance, designed to show off the stars. Such plays were filled with exaggeration, fantasy, illogicality, adn what some critics consider outright silliness. Thus, some claim, the lack of the lost material is no great loss." Quoted from: Kabuki Plays on Stage: Villainy and Vengeance, 1773-1799, pp. 216-217.

Below is an image by Toshikata (1866-1908) of an empress at the Jakko-in.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Jūnishi |

十二支 じゅうにし |

The 12 signs of the zodiac. These include the rat, ox, tiger, hare, dragon, snake, horse, goat, monkey, cock, dog and boar.

In Chinese Symbolism and Art Motifs by C.A.S. Williams (Castle Books, 1974 edition, p. 412) it states: "The first explicit mention of the practice of denoting years by the names of animals... is found in the history of the T'ang dynasty, where it is recorded that an envoy from the nation of the... (Kirghis?) spoke of events occurring in the year of the hare, or of the horse. It was probably not until the era of the Mongol ascendancy in China that the usage became popular; but according to Chao I... -A.D. 1727- traces of a knowledge of this method of computation may be detected in literature at different intervals as far back as the period of the Han dynasty, or second century A.D."

Later Williams notes that "Professor Chavannes has written a learned article to prove that the group known as the Twelve Animals was borrowed fromt eh Turks, and was used in China as early as the first century of the Christian era..."

"The figure of 360, which we recognize as the number of degrees in the circle, is almost as good as a Babylonian signature. By the early fifth century B C the Babylonians had the makings of a co-ordinate system, for they had by then begun their division of the zodiac into twelve 'signs' of equal length, naming them after the constellations or important star groups..." (Quote from: The Norton History of Astronomy and Cosmology, by John North, W. W. Norton & Company, 1995, p. 39)

Joseph Needham in The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China: 2 (Cambridge University Press, 1981, p. 111) states: "It has been suggested that both systems [the Chinese and the Indian-Arabic] were derived from a Babylonian 'lunar-zodiac' which was received by all Asian peoples. Certainly in the library of the Assyrian king Assurbanipal (668 to 612 B.C.) at Ninevah, there are some cueiform tablets whose contents date from the second millennium B.C. Thees show three concentric circles, divided into 12 sectors." |

|

Junshi |

殉死 じゅんし |

Ritual suicide - "sacrifice one's own life in order to follow one's lord to the land of shades". According to an ancient Chinese source it was banned in 646, but had to be outlawed several times later through the centuries. "Despite this, many samurai and servants killed themselves when their master or lord died. The last example of junshi occurred when General Nogi and his wife committed suicide when Emperor Meiji died in 1912. Throughout the Edo period, it was common practice for samurai close to a lord to commit seppuku when the lord died. Junshi was considered a giri (moral obligation). But many daimyo forbade it and, in 1683, the rules in the Buke-shohatto banned it again." Quoted from: Japan Encyclopedia by Louis Frédéric, p. 437.

This information differs somewhat with that given by Marius Jansen in his The Making of Modern Japan (pp. 43-44): "At the time of [the shogun Iemitsu's] death five of his senior aides accompanied him in ritual suicide (junshi), a procedure that was later, in 1663, forbidden by the bakufu." |

|

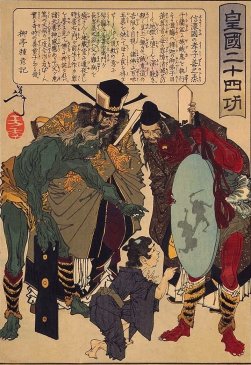

Jūō |

十王 じゅうおう |

The Ten Kings are the ten judges of the dead. |

|

Juzu |

数珠

じゅず |

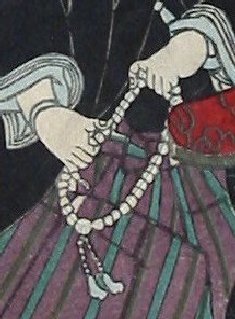

A Buddhist roasary: "Buddhist rosaries, have 108 beads, symbolizing the 108 worldly sins. One moves each bead in prayer to be saved from committing the particular evil it stands for." This originally accompanied the prayer namu-amidabutsu or "May the soul rest in peace." For practical purposes there are shorter strings of 54, 27 or even as few as 14 beads. The example shown to the left appears to be one of those. A shortcut to going through all the beads individually can be made simply by holding them or by clasping them between hands held together in prayer in various configurations. In this case the longer strands are frequently wound around the hand for convenience sake.

"Juzu beads are generally made of iron, copper and gold alloy, crystal, coral, amber, glass, various kinds of hard and fragrant wood and many other materials." Kyoto was known for the production of these items and some of them could be quite expensive.

Source and quote from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 514.

Last night, February 15, 2006, I was reading a passage in a novel which helped reinforce one of the points of information made above: "To keep count of the thousands of paces, Huree Chunder's experience had shown him nothing more valuable than a rosary of eighty-one or a hundred and eight beads, for 'it was divisible and sub-divisible into many multiples and sub-multiples."

Quote from: Kim, by Rudyard Kipling, Penguin Books, 1989, p. 211. 1 |

|

Kabuki-za |

歌舞伎座 かぶきざ |

A major kabuki theater in Tokyo 1 |

|

Kabuto |

兜

かぶと |

Helmet: "As protection for the head, the kabuto was clearly one of the most important component parts in a set of armour. As such, a considerable degree of consideration was given to its construction. The aforementioned form, though strong, was complex and difficult to produce as it required the smith to create a low round helmet bowl from a series of flat iron plates. Thus over time such work became the speciality of the most talented of smiths, or katchû-shi, many of whom, like any successful artisan, developed a reputation for excellence that earned them both the patronage and respect of the warriors as well as a following of budding apprentices. The various characteristic features and distinctive idiosyncrasies that these pupils learned to replicate, eventually evolved into prescribed principles that formed the foundations around which individual guilds or schools of armour makers grew." Quoted from: The Watanabe Art Musuem Samurai Armour CollectionVolume I ~ Kabuto & Mengu, vol. 1, Trevor Absolon, p. 18.

The photo to the left of the helmet was posted by Thierry Bernard at commons.wikimedia. It was being shown in Dallas on loan from the Musée du Quai Branly, Paris. |

|

Kaede |

楓

かえで |

Maple leaf: John W. Dower in his The Elements of Japanese Design (p. 62) notes "...the word for maple, is itself suggestive - the pronunciation puns on 'frog's foot,' which is how the ancients apparently described the leaf, while the single ideograph used is made up of the elements for tree and wind, conveying a rather gentle image of rustling foliage." |

|

Kaemon |

替紋 かえもん |

An alternate or substitute crest meant specifically for use by only one actor. For example, a crane was used by Utaemon III while Danjūrō VII's was a peony and Kikunojō V's was a chrysanthemum. For a more general use see our entry on mon. |

|

Kaeru (also pronounced kawazu) |

蛙

かえる

|

Frog - The frog is one of only two creatures mentioned in the preface of the Kokinshu: "The songs of Japan take the human heart as their seed and flourish as myriad leaves of words. As long as they are alive to this world, the cares and deeds of men and women are endless, so they speak of things they hear and see, giving words to the feelings in their hearts. Hearing the cries of the warbler among the blossoms or the calls of the frog that lives in the waters, how can we doubt that every living creature sings its song?"

Both photos to the left are from botanic.jp. The bottom image is a Japanese tree frog. The image above is from an 19th century Japanese netsuke showing the underside of a mushroom with a frog. It is from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

|

Kaerumata |

蛙股

かえるまた |

Often translated literally as 'frog's legs' it can also be translated as 'frog's crotch'.

"In these temples the long cornice beams, which extend horizontally from the brackets, requiring additional support between the principal corbelled clusters, are partly upheld by minor arrangements of bracketing supported upon ornamental strutting of a curved form. The native name (Kaeru-mata) means frog's-leg form, a name which well expresses the general outline of the arrangement... Between the pairs of curiously curved struts, which spread outwards like the legs of a frog, a short central post is often placed. This is rounded at top and bottom, ending at the top in a curved boss or tail projecting over the front of the supporting lintol. When the post is not used between the struts, the curved space enclosed is filled with a panel of carving, in high relief, representing some such subject as the stork and pine tree, or chrysanthemum and jay... Sometimes the struts themselves are elaborately carved to represent clouds or water. The flat spaces left between principal and secondary bracket supports are decorated, sometimes in colour, and sometimes by means of oblong panels of carving which is mostly very realistic in its execution. The faces and soffits of the cornice beams are decorated with polychromatic diapers upon a white or gilded ground; and the intermediate spaces are boarded, and the intermediate spaces are boarded, in flat or curved surfaces, with small projecting ribs." Quoted from: Transactions of the Royal Institute of British Architects, Volume 2, 191.

The image to the left was posted at Wikimedia commons by Reggaeman. The image above was posted at the same site by Fg2. It represents the kaerumata at the Kitano Tenmangū. |

|

Kagami |

鏡 かがみ |

This is the Japanese word for mirror, but it is often used in a metaphorical or more expansive sense in reference to print titles. |

|

Kagami biraki |

鏡開き

かがみびらき |

It might be best if you read the entry on kagami mochi below first.

The kagami biraki is the ritual breaking of the mochi created for the New Year's celebration. It is allowed to harden in the open air for a number of days. Due to a natural process of desiccation this stack of rice cakes often shrinks somewhat and cracks too. Then on different days across Japan - starting around January 11th and in the following days - based on local custom the kagami mochi is broken up either by hand or by hammer. It would seem that cutting the stack might well be considered a bad choice among traditionalists. The crumbled pieces can then be put into several different types of soups and ingested in the hope that this will bring good luck and protection throughout the new year.

The graphic to the left was created especially for us by David Wilcox. Thanks David! I think it looks great and I'm picky. |

|

Kagamibuta |

鏡蓋

かがみぶた |

A type of netusuke - "The kagamibuta ("mirror lid") is a rounded shape having a disk, or lid, commonly of metal, set into a bowl of ivory or wood. This Hd can be opened by releasing the tension on the cord, which is strung through the back of the bowl. Decoration was usually restricted to the metal, but in rare examples the bowl was elaborately carved as well."

Quoted from: Netsuke: Masterpieces from the Metropolitan Museum of Art by Barbra Teri Okada, pp. 11/13.

The item to the left is from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

|

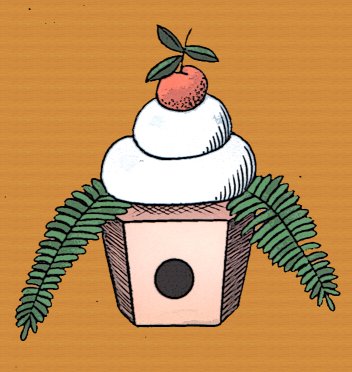

Kagami mochi |

鏡餅

かがみもち |

A "...big fat round rice cake in the traditional shape of a mirror (kagami). Two or three of these cakes, of different sizes, one on top of the other, form the basis of the New Year decoration in homes." Topped with bitter orange (daidai), dried persimmons (kaki), kelp (konbu) or any one of an assortment of other traditional items. "On January 11 the cakes are usually cut up and served in zōni [mochi in soup] or shiruko [a sweet soup].

Quotes from: A Dictionary of Japanese Food: Ingredients and Culture, by Richard Hosking, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1996, p. 67.

Now here is the rub: In a web site devoted to children kagami mochi is discussed with definite clarity and it states that this now hardened New Year's decoration is definitely not cut because that has such bad connotations. Instead they say that it is broken up by hand or smashed with a hammer - as though that wouldn't have bad connotations too. This ceremony is referred to as kagami biraki (鏡開き).

Now here is another rub: When looking up the definition of kagami biraki the very credible sites I checked referred to it as the cutting up of the mochi. They all can't be right. Moral: Never trust your sources including this one.

On New Year's Eve I received an e-mail from C. S. complimenting me my work on this web site and wishing me a happy holidays. C. S. had found the site through a search on Google on mochi pounding. For that reason I am dedicating this first index/glossary entry for 2006 to C. S. Keep them coming please. Thanks C. S.!

The graphic to the left was created especially for this site by David Wilcox. |

|

Kagaribi |

篝火

かがりび |

A bonfire, watch fire or a fire on a tripod stand used in night fishing. The detail to the left is from a print by Eisen illustrating cormorant fishing. See our entry on ukai for further information.

The rod used to hold the fiery basket is called a kagaribo (篝火棒?). |

|

Kage-e |

影絵

かげえ |

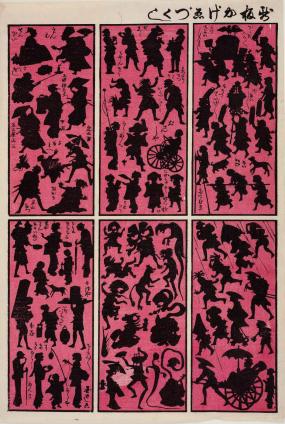

Shadow or silhouette pictures - "A shadow picture that consists of shadow images of people and animals [or spectres], as if light were cast from behind." This emended quote is from the Kumon Museum of Children's Ukiyo-e.

The image to the left, a

possible Kunitoshi, is from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts,

Boston. It is entitled 'Newly Published Collection of Shadow Pictures' (Shinpan

kage-e zukushi - 新板かげゑづくし). |

|

Kagema |

蔭間

かげま |

Kagema is an interesting term. The first character, 蔭, means 'shadow' while the second part, 間, means 'place' or 'space'. Timon Screech in his The Shogun's Painted Culture: Fear and Creativity in the Japanese States, 1760-1829 gives a different reading: "...kabuki was the hub of male prostitution. Attractive actors supplemented their earnings by accepting paid engagements with fans. Full-time rent-boys took the title 'stagehands' (kagema) to excuse their hanging about at night: the word literally meant 'in the shadow' (i.e., off-stage), but the pun was obvious. (Published by Reaktion Books, 2000, p. 139) Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary (1931, p. 644) defines kagema as 'professional catamite'.

|

|

There were special assignation teahouses specializing in these young men. Stephen O. Murray in his book Homosexualities discusses these places. "The increasingly rich and dominant class of merchants (townsmen; chonin) became patrons of theater and of impecunious youth. and the ideal in boys onstage and off became decidedly more effeminate. By the late seventeenth century, male houses of prostitution with effeminate boys existed alongside female houses, especially in the larger cities. There were at least fourteen wards (machi)... with kagema-jaya (catamite teahouses) during the 1760s... Three of these were in the theater quarters. The rest were adjacent to shrines.... In fact, one house employed as many as one hundred boys for sexual purposes..." (Homosexualities, University of Chicago Press, 2002, pp. 176-77)

In "Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan" published by Asiatic Society of Japan in 1891 there is a long list of the categories of citizens. Number 30 gives us "Jorō (prostitutes), yarō (low fellows), and kagema (boys used for sodomy), are not to be permitted in the mura, and if they arrive from other parts, houses are not to be rented to them." (p. 182)

Mark McClelland contributed an essay, Japanese Queerscapes: Global/Local Intersections on the Internet, in Mobile Cultures. In it he summarizes the confusion over translating Japanese terms into English: "Japan has a long tradition of transgendered men offering sexual services to gender-normative men. In the Tokugawa period (1600-1867), transgendered prostitutes (kagema), who were often affilitated with kabuki theaters, would offer their services to male members of the audience. In the Taishō (1912-1927) and early Shōwa (1927-1989) periods this role seems to have been taken over by okama [御竈], a slang term for the buttocks that, when applied to male homosexuals, means something like the English 'queen.' In the 1960s and 1970s, the term geiboi [ゲイボーイ] (gay boy) referred to cross-dressing male hustlers, and gei (gay) still carries transgender connotations today. Giving fixed content to any Japanese terminology dealing with sexual- or gender-nonconformist individuals is problematic and producing English-language equivalents almost impossible." (Quoted from: Mobile Cultures: New Media in Queer Asia, Duke University Press, 2003, pp. 58-59)

"...yarō, as well as kagema and iroko, were terms for male prostitutes during the Edo period. Until the beginning of the Meiji period yakusha kai, 'to buy an actor,' was an expression as familiar to the people as jorō kai, 'to buy a prostitute,' or geisha kai, 'to buy a geisha'... Yoshizawa Ayame and Segawa Kikunojō, famous onnagata of the Genroku period, has both started their career as iroko, as 'sexy boys.' Iroko who also appeared on stage were called butaiko, 'stage boys.' In the Kyōhō era (1716-36) the iroko reached the peak of their popularity and, at least until the Tempō era in the middle of the nineteenth century, every theater had its own group of iroko, who were managed either by the 'owner' of the theater or popular actors, musicians, reciters, or by theater teahouses or irokoya, brothels for male prostitutes..." (Quoted from: "From Pleasure to Leisure: Attempts at Decommercialization of Japanese Popular Theater", by Annegret Bergmann, in The Culture of Japan as seen through its Leisure, SUNY Press, 1998, pp. 254-55)

Stephen O. Murray in Pacific Homosexualities (published by the Writers Club Press, 2002, p. 278-9) quotes a Japanese scholar who tell us "...that after the end of the 18th century the kagema mostly dressed themselves as girls, while during the Genroku period (1688-1703) they had dressed themselves gracefully as beautiful young men..."

Hepburn, who gave us one of the first useful Japanese-English dictionaries, translated kagema as "A boy used by sodomists."

"While the new regulations had a restraining effect on the overtly erotic content of the performances, they had no effect on the brisk off-stage sexual trade of the young male actors. Called tobiko, “fly boys,” their numbers grew rapidly to meet the demands of the growing urban population enjoying the prosperity of Tokugawa Japan. The fly boys of the theater were quickly joined by other, full-time male prostitutes, called kagema, who worked in tea houses and in brothels, known as kagemajaya, which sprang up quickly in the theater districts. The fly boys and the kagema were immensely popular among the merchant class and cultural sophisticates of the day, who practiced a debauched form of nanshoku, wining and dining the young men in a caricature of the noble love of the samurai. The young kabuki stars were much in demand among wealthy patrons who competed with each other for the privilege of purchasing their services. The more beautiful actors even had devoted followings and were celebrated like the Hollywood stars of today." Quoted from: The Origins and Role of Same-Sex Relations in Human Societies by James Neill, p. 290. |

||

|

|

||

|

Kagerō |

蜻蛉

かげろう |

Mayfly: Although the characters 蜻蛉 are pronounced kagerō they can also be pronounced tombō which is the word for dragon- and damselfly. On the other hand 蜉蝣 also represents the mayfly (or ephemera) and is read as kagerō.

The image above of the (French) mayfly, Ephemera danica, was taken by Jean Pierre Hamon and placed in the public domain at http://commons.wikimedia.org/.

The Genji mon or crest to the left indicates chapter 52 of the Tale of Genji. At the beginning of his masterful translation of The Tale of Genji (Vol. 2, published by the Penguin Group, 2001, p. 1045) Royall Tyler tells us why this chapter is entitled Kagerō:

The kagerō ("mayfly") hatches in summer and dies only a few hours later. The chapter title comes from the chapter's closing poem, by Kaoru.

"There it is, just there, yet ever beyond my reach, till I look once more, and it is gone, the mayfly never to be seen again."

The mayfly lives as an adult only for a day or two during which the mate, molt and lay their eggs. They appear in huge numbers at dusk in the early spring. The males swarm and when a female flies into their group one male grabs her and they fly off together. You know the rest of the story. One other unusual factor is that their mouths are not completely formed so they do not eat. |

|

Motoori Norinaga (1730-1801: 本居宣長) tells us that seimei (せいめい) is another term used for mayfly.

Source: The Poetics of Motoori Norinaga: a Hermeneutical Journey, by Norinaga Motoori, translated by Michael F. Marra, University of Hawaii Press, 2007, p. 63.

When written in kana, i.e., かげろう, can refer to either the shimmering heat of summer (陽炎), the mayfly (蜉蝣 or 蜻蛉) or something ephemeral. Because of these homonyms puns are readily at hand.

In Essays in Idleness: The Tsurezuregusa of Kenkō the author wrote: "If man were never to fade away like the dews of Adashino, never to vanish like the smoke over Toribeyama, but lingered on forever in the world, how things would lose their power to move us! The most precious things in life is its uncertainty. Consider living creatures - none live so long as man. The May fly waits not for the evening, the summer cicada knows neither spring nor autumn. What a wonderfully unhurried feeling it is to live even a single year in perfect serenity."

Quoted from: Essays in Idleness: The Tsurezuregusa of Kenkō, by Yoshida Kenkō, translated by Donald Keene, Columbia University Press, 1998, pp. 7-8. (These essays were probably composed between 1330-32.)

Alfred Lord Tennyson (1809-92) in his poem Maud deals with the same issues of transience:

For nature is one with rapine,

a harm no preacher can heal;

For the mere reason that I like it I am going to quote the next stanza:

We are puppets, Man in his pride, and Beauty fair in her flower; Do we move ourselves, or are moved by an unseen hand at a game That pushes us off from the board, and others ever succeed? Ah yet, we cannot be kind to each other here for an hour; We whisper, and hint, and chuckle, and grin at a brother’s shame; However we brave it out, we men are a little breed.

The mayfly in the West is also known as a drake fly. |

||

|

|

||

|

Kago |

駕篭

かご |

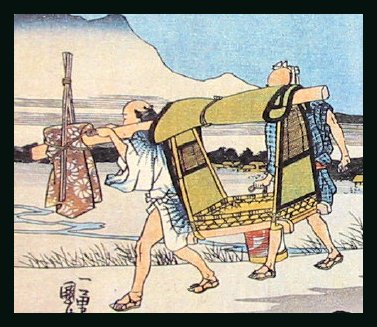

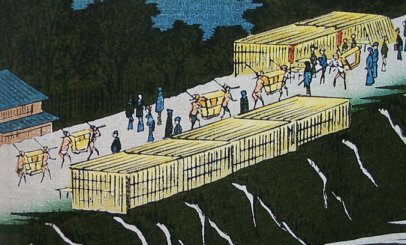

A palanquin or litter used for travel. The roads were tamped down, but unpaved and wheeled vehicles were not used generally prior to modernization starting in the late 19th century. One author noted that when Westerners started arriving in Japan after Perry's visit they found these litters very uncomfortable. They were too squat as carriers for the traveler to sit up straight and too short for them to straighten their legs. 1 |

|