|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

Kutsuwa thru Mawari-dōrō |

|

|

The orange flowers will be

used to mark new additions |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Kutsuwa, Kuzuryū, Kyahan, Kyōgō, Kyōka, Kyōkatabira, Kyokki, Kyokuba, Kyōsoku, Kyūdō, Kyūri, Lake Biwa or Biwako, Richard Lane, Samuel Leiter, Machi, Maedate, Maegami, Magaki,

Magatama, Mage, Makai,

Makura sōshi, Makyō, Maneki neko, Manji, Manji, Manji tsunagi, Man'yōgana, Man'yōshū, Marumage, Maru ni mitsu kashiwa, Matsu, Matsuba, Matsubame-mono, Matsukawa-bishi, Matsumoto Koshirō V, Matsuri, Mawari-dōrō

轡, 九頭龍, 脚絆, 校合, 狂歌, 経帷子, 旭旗, 曲馬, 脇息, 弓道, 胡瓜, 琵琶湖, 人間国宝, 町, 前立, 前髪, 籬,

勾玉 or 曲玉, 髷, 魔界,

枕草子, 魔鏡, 招き猫, 萬治 or 万治, 万字, 万字繋 or 卍繋, 万葉仮名, 万葉集, 丸髷, 丸に三つ柏, 松, 松葉, 松羽目物, 松皮菱, (五世)松本幸四郎, 祭り, 回燈籠, |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Kutsuwa |

轡

くつわ

|

A bit motif: "These small pieces on each side of the horse's bit not only gave a martial impression when used as crest motifs, but also were later adopted by several Christian families because of the 'hidden cross' design."

Quoted from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, published by Weatherhill, 1991 edition, p. 106.

Lafcadio Hearn in his writings mentioned a cricket, the kutsuwa mushi ( 轡虫) or bridle-bit-insect, which made the sound the rings attached to the sides of each bridle would make. He even quotes a poem by Izumi Shikibu (和泉式部) who was born in the late 10th century.

Listen! His bridle rings - That is surely my husband Homeward hurrying now Fast as the horse can bear him! Ah! My ear was deceived! Only the Kutsuwamushi!

Hepburn says that a homonym for kutsuwa means "A prostitue house," but doesn't mention is it is a proper or common noun.

To the left we have added a detail from a Gyokushū print in the Lyon Collection. It shows a pair of kutsuwa lying in a tub next to a packhorse driver. It dates from 1834. |

|

Kuzuryū |

九頭龍

くずりゅう |

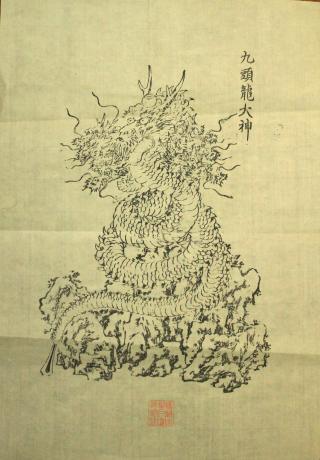

A 9-headed dragon of folklore. Centered at Togakushi in Honshū. It originally appeared in literature of the T'ang dynasty in China.

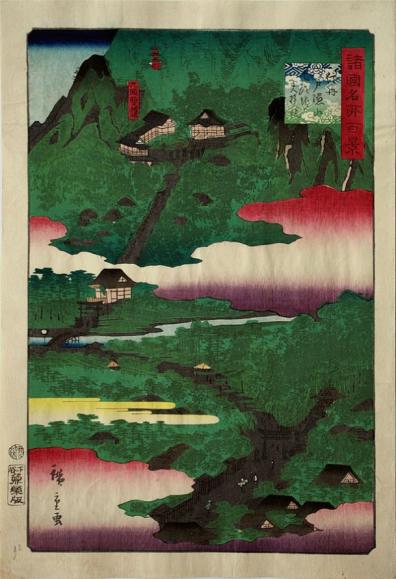

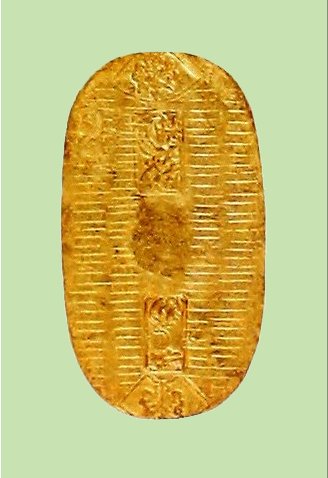

The image to the left is an ofuda of a Kuzuryū. The image shown above is a Hiroshige II print of the shrine at Togakushiyama. |

|

Kyahan |

脚絆

きゃはん |

The leggings worn by a pilgrim. See our entry on ajirogasa on our first index/glossary page to see a pilgrim wearing kyahan.

The photo to the left are leather kyahan worn by a samurai or one of his attendants. It was posted at Pinterest, but had originally shown up at the Japanese Wikipedia site. |

|

Kyōgō |

校合 きょうごう |

Black ink keyblock print used for making color blocks.

David Bull (デイビッド.ブル) of the Baren Forum adds that after the proof prints were pulled they were sent to the designer, i.e., artist, who would indicate what colors were to be used where. 1

Question: Why do any kyōgō still exist today? Hiroshi Yoshida provides the answer. "A few more impressions than the number of the colours to be used in the print must be taken. If ten colour blocks are anticipated, fifteen may be necessary." (Japanese Woodblock Printing, 1939, p. 31) ¶ In the 20th century other colors were used in printing kyōgō. "...they are often printed in red, green, or blue, in order to bring out the feeling which the artist desires." (p. 75) |

|

Kyōka |

狂歌 きょうか |

Literally "mad verse" - a 31 syllable comic poem |

|

Kyōkatabira |

経帷子

きょうかたびら |

A white kimono in which a dead person is dressed. Used in Shinto ceremonies or by Buddhists sometimes decorated with sutra texts.

"The deceased was left on his or her mattress until the priest arrived to read the first sutra chanting (makura-gyō). When the priest had finished the recitation and the sun was down, the bereaved performed a bathing ritual (yukan) for the deceased; they shaved his or her head (the sign of a Buddhist disciple) and clipped his or her nails... After the bathing ceremony, the deceased was dressed in a white death robe, which symbolized pilgrimage, a triangular headcloth (zukin), a pair of hand guards (tekkō), a robe (kyō-katabira),a pair of knee guards, and a pair of Japanese-style socks (shiro-tabi), all of which prepared the deceased for his or her journey to gain Buddhahood. Three women of the community followed strict rules in making the death robe. They measured the cloth by hand instead of with a ruler, tore the cloth instead of cutting it with scissors, sewed the seams so that the stitches were visible, left the ends of the threads unknotted, and made no collar. Making the garment different from the clothes worn by the living emphasized the contrast between life and death (Matsudaira, 189). The deceased, dressed in the death robe, was placed in a round, cask-like coffin (maru-kari), which forced the corpse into a sitting posture with the knees bent." Quoted from: The Price of Death: The Funeral Industry in Contemporary Japan by Hikaru Suzuki, p. 43.

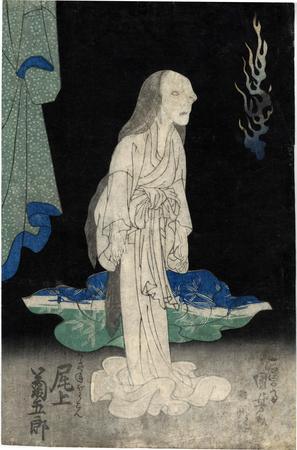

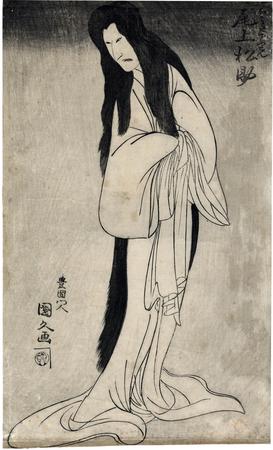

Both of these images, the one to the left and the one above are from the Lyon Collection. They represent ghosts in kabuki plays. The one to the left is of Oiwa by Kuniyoshi, while the one above is of Iohata by Kunihisa. |

|

Kyokki |

旭旗

きょっき |

Rising Sun Flag: It is the red and white of the flag which is important to us here. White represents the yin (陰) or male element and red the yang (陽) the female. Elsewhere I noted: "Another question arises from something else I read a number of years ago, but for the life of me have been unable to find again to check my sources. The quote said that the red and white of the Japanese flag represented the red or female element and the white was the male. It doesn't take a stretch of the mind to understand the sexually oriented use of these symbolic colors. The contrast of the two in combination is - if this is true - a clear analogy to the yin-yang concept."

Well, I finally sound something on the subject, but not exactly what I was looking for. "Let us return to the red and white, which colors have had a metaphorical resonance across Asia, from ancient Iran to Japan. The Chinese conception, reflected in the funerary rituals, is that the (red) flesh comes from the mother, whereas the (white) bones come from the father. More specifically, the mother's 'red drop' contributes the skin, blood, flesh, fat, heart, and soft, red viscera; whereas the father's white drop contributes the hair, nails, teeth, bones, veins, arteries, ligaments, semen - in other words, all that is white, hard, structural. This is very much like the Greek conception, described by Aline Rousselle, in which semen goes to build the 'noble white parts.' Therefore, a woman who wants a son must 'whiten' or 'masculinize' herself. According to Aristotle, 'Man produces sperm because he is a warm nature, such that he possesses a capacity for bringing about an intense concoction of the blood, which transforms it into its purest and thickest residue: sperm or male seed. Women cannot perform this operation. They lose blood, and at their warmest can only succeed in turning it into milk... Thus, the ultimate difference between the sexes lies in the fact that one is warm, and dry and the other is cold and wet, qualities that reveal themselves in their aptitude or inaptitude for achieving concoction.' Incidentally, this distinction is presented as the ultimate rationale and justification of the androcentric social order. The Egyptian theories of reproduction, too, ascribed the bones to the male principle and the flesh to the female."

Quoted from: The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender, by Bernard Faure, published by Princeton University Press, 2003, p. 83.

A side note: "According to an interesting (and widespread) Japanese belief, the gender of the child is said to depend on who gets the most pleasure from sexual intercourse. According to the Shaseikishū [13th c. - 沙石集], for instance, the conscience is formed by the fusion of the 'white drop' of the father and the 'red drop' of the mother; and depending where the sexual pleasure was, the child will resemble the father or the mother." (Ibid., p. 85)

Another fascinating side note which has nothing whatsoever to do with the Japanese flag, but does pertain somewhat to the text above: Faure quotes St. Jerome: "As long as a woman is for birth and children she is as different from man as body is from soul. But when she wishes to server Christ more than the world, then she will cease to be a woman and will be called man." (Ibid., p. 128)

For more on the curse of 'redness' look at our discussion of the Blood Pool of Hell on our page devoted to the Courtesan from Hell - a print by Kunisada II.

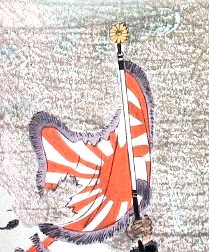

The image of the flag of the Rising Sun above is shown courtesy of Thommy at http://commons.wikimedia.org/. The detail to the left is from a triptych by Koson.

See also our entry on koshimaki or the red undergarment traditionally worn by Japanese women. You will find it on our Kogai thru Kuruma page. And see our entry on the hi-no-maru on our Hil thru Hor page. |

|

Kyokuba |

曲馬

きょくば |

Circus/equestrian feats: "Japan has had its own circus for nearly 500 years. It is called kyokuba or trick horse-riding was at first its main attraction. Kyokuba started in the middle of the Muromachi period (1394-1573), and from its very beginning consisted of fancy horse-riding, acrobatic acts, comic plays and performances by monkeys and dogs."

Quote from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 483.

The image to the left is a detail from a Yoshiharu print from 1871 showing a troupe (kyokuban - 曲馬団) of female, European riders. Click on the number to the right to see the full print.

A stunt rider is a kyokubashi (曲馬師). 1 |

|

Kyōsoku |

脇息

きょうそく |

Armrest: "A support board (hyōban) measuring approximately 18 by 6 inches...was elevated on legs at either end, and covered with a cotton-padded cushion. Armrests might be made of imported karaki woods, zelkova, or paulownia, or lacquered and decorated in mother-of-pearl inlay or maki-e."

Quoted from: Traditional Japanese Furniture, by Kozuko Koizumi, published by Kodansha, 1986, p. 102. 1

I was wondering in general how old this type of furniture was and was surprised to find that it is mentioned in the oldest piece of Japanese literature, the Kojiki (古事記) which was presented to the Imperial Court in 712 A.D. Toward the end of this tale Wodö-pime of Kasuga sings to the Emperor Yūryaku. In her song she wishes she were the armrest the Emperor leans upon. |

|

Kyūdō |

弓道 きゅうどう |

Archery: literally 'the Way of the bow'. "Archery is also resorted to as a means of divining whether the harvest will be abundant.... On Janualry 14th of the lunar calendar... the method used is archery on horseback (yabusame). The inclination which the arrow takes on the target gives the desired information about the next crops." Quoted from: Shinto: At the Fountainhead of Japan by Jean Herbert, p. 153. |

|

Kyūri |

胡瓜

きゅうり |

Cucumber: A kappa's favorite food.

Now...I have a confession to make. The cucumber to the left is not a Japanese cucumber - as far as I know. I bought it in a local grocery store today. I even searched for the one which I thought a kappa might find most attractive. Be that as it may, considering all of the international trade going on this cucumber may well come from Ecuador or Chile or some such place, but definitely not Cuba or North Korea. Of that I can be fairly sure. Besides, all I cared about was finding a decent looking kyūri for your visual and intellectual delectation. Now there's food for thought.

Kiuri is an alternate spelling for kyūri listed in the text volume of the Utamaro catalogue from the great British Museum show. I mention this because a scholarly friend of mine who is fluent in Japanese questioned my original use of kiuri. I revised my entry to this, i.e., kyūri, Anglicized variation.

The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, text volume, entry #119, p. 125.

Kyūri literaly means foreign 胡 melon 瓜.

Orikuchi Shinobu (折口信夫: 1887-1953) said that at some festivals frightening faces were drawn on cucumbers and they were then sent floating downstream. Since 胡瓜 can be parsed to mean foreign melon then painting it with an intimidating mug and sending it away is symbolic of ridding a village of evils brought from the outside.

Several modern Japanese scholars believe that the kappas love of cucumbers is more modern than ancient. |

|

Lake Biwa or Biwako |

琵琶湖 びわこ |

Japan's largest freshwater lake. 8 of its famous views have inspired many artists. 1 |

|

Lane, Richard |

|

Major author of works on Japanese prints including Hokusai: Life and Work 1 |

|

Leiter, Samuel |

サミュエル・L・ジャクソン |

|

|

Living National Treasure(s) |

人間国宝

にんげんこくほう

|

Starting in the late 19th century during the Meiji Period the Japanese began to recognize the importance of preserving and protecting tangible national treasures. In 1929 the Preservation of National Treasures Law (Kokuhō Hozon Hō) was enacted. "In the immediate post-World War II years a new effort to nurture traditional crafts and performing arts on a national basis resulted in the promulgation of the 1950 Law for the Protection of Cultural Assets (Bunzaki Hogo Hō), amended and expanded in 1954 and 1970. The 1950 law covered certain intangible assets (mukei bunka-zai) as well as intangible objects." Artist/craftsmen became known as 'bearers of important intangible cultural assets' or jūyō mukei bunkazai hojisha [重要無形文化財保持者]. This included everything from ceramicists, wordsmiths, fabric artists, lacquerers, doll makers, woodworkers, and performers and practitioners of music and theatrical arts, etc. |

|

"The first list of 31 persons designated by the government for 28 categories of skills was made known on 15 February 1955 and the public immediately transferred the word kokuhō, meaning national treasure, from the 1929 law referring to the preservation of important objects, to the individuals named in the first list, calling them Ningen Kokuhō (Human National Treasures). The termn has been used ever since, despite protestations on the part of the Ministry of Education and he designees themselves that the program is designed not to honor individuals, but to ensure that certain traditional skills will be transmitted for future generations."

65 different skills have been recognized. Each spring the list is reviewed. If an honoree dies he or she is not necessarily replaced with another. Sometimes it is a whole group like a dance troupe which is recognized. A small annual stipend is given to each individual or group. "There is no specific teaching requirement, but the honored individual is expected to find and train apprentices and successors..." Recipients are expected to leave full records, including films, or their practices and to participate in annual exhibitions.

Source and quotes: "Living National Treasures" by Barbara C. Adachi in vol. 5 of the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan (pp. 60-1).

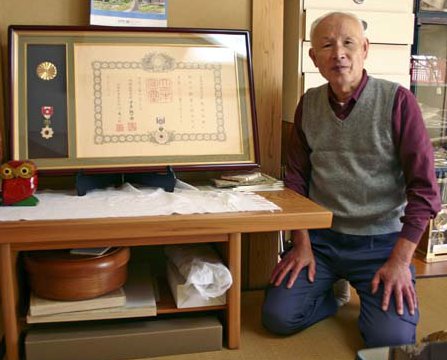

The top image shown above is a photo of Iwano Ichibei kneeling next to his certificate. He is a master paper maker who provides the finest sheets used for woodblock printing. (See our entry for mimi-tsuke below.) The bottom image of the Washington Monument with blossoming cherry trees is by Kawase Hasui (川濑巴水). He was named an honoree in 1955, but died in 1956. I don't know of any other ningen kokuhō named for woodblock print artistry since then. Itō Shinsui (伊東深水) was honored in 1950 when his print oeuvre was recognized as a national treasure, but that was before the 1955 designations although he lived until 1972 and could easily have been included in the list, but wasn't. If anyone out there knows of other print honorees please let me know and bring irrefutable proof. |

||

|

|

||

|

Machi or chō |

町 まち or ちょう |

Machi is one of those words which can be translated into several different meanings: town, block, neighborhood, street or road.

"Quant à machi, ce mot était surtout utilisé aux XVe et XVIe siècles pour caractériser de petites agglomérations qui avaient diverses origines et fonctions: jôka-machi (ville seigneuriale, littéralement « ville sous le château »), minato-machi (« ville port »), monzen-machi (« ville en face d'un temple ») distincte de dejinai-chô (« ville temple»), ichiba-machi (« ville marché ») ou shukuba-machi (« ville relais de poste »). Machi sera ainsi longtemps en usage pour désigner une catégorie d'agglomération de population distincte de la ville (shi) aussi bien que du village (mura) et en général dotée d'institutions d'autogouvernement. En outre, à Edo et dans les grandes métropoles, machi était utilisé pour désigner les secteurs de l'agglomération urbaine réservés à la classe des chônin, les et artisans (ou « bourgeois » , « gens de ville ») placés au bas de la de la hiérarchie sociale. Dans ce contexte, machi désignait donc une division élémentaire de l'espace urbain, ce qui le rapprochait de chô. Mais cette « ville dans la ville », si l'on veut, était, à l'époque d'Edo, exclusivement associée à un statut juridique particulier des habitants et des sols. D'où l'opposition du langage commun entre shitamachi, la ville basse ou des petites gens, et yamanote, la ville haute ou ville des grands. ¶ Les noms de machi-chi dérivaient de la profession principale de leurs habitants, de leur région ou ville d'origine, du nom du fondateur ou du daimyô qui avait fait construire le secteur." Quoted from: Les divisions de la ville, edited by Christian Topalov, pp. 195-196. |

|

Maedate |

前立

まえだて |

A crest attached to the front of a helmet. Some dictionaries define it as a plume or pompom.

An interesting aside: When parsed the kanji characters for maedate mean separately 前 'in front' and 立 'stand up' or 'erect'. Not surprisingly these two combined also deal with prostate issues.

|

|

Maegami |

前髪

まえがみ |

Forelock: If anyone had told me years ago that I would be writing about forelocks and I wouldn't have believed them and would have laughed out loud. Nor would I have imagined that forelocks have historically played such an important role in Japanese culture. (See our entry on murasaki bōshi.) Who would have thought it. Turns out that the forelock on young men in Japan was supposedly an extra special turn on for many homosexuals. The only forelocks I remember from my youth were those on Superman (スーパーマン) and some popular singers. If I wasn't wearing a crew cut or a flattop I would occasionally have a forelock. Still do sometimes. However, either because times have changed or for cultural reasons or for a lack of a certain physical pizzazz I was not the focal point of older men. (I am not complaining.)

Samuel L. Leiter wrote: [A] " 'Forelock wig,' worn by a youth whose forelock (maegami) still has not been cut off, an action that was part of the celebratory rites surrounding his passage into manhood (genpuku [元服]). There are a variety of names for the maegami. Those split down the center into two parts are the hachiware [はちわれ], those stiffened with pomade are the aburakomi [あぶらこみ], those fashioned like a pompon are the tsukamitate, and so on." (New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of kabuki jiten, p. 383)

"Plays about male-male love filled the repetoire during the time female impersonation was banned (1651-54), and continued after the ban was replaced by a 1654 regulation of permissible actors hairstyle... The long forelocks (mae-gami) were the glory of the boys' appearance, and the shearing of the wakashu [a young male actor] was a shocking mortification to actors and a source of mourning for the patrons. Ihara wrote that shaving the mae-gami was 'like seeing unopened blossoms torn from the branch.' One source said a young man without his forelock was no longer a young man. "He was, as they said at the time, no more than a peasant. Finding that their beautiful wakashu were no longer wakashu, their admirers, it is said, wept tears of blood." However, enterprising actors found that by using a purple cloth they could remain as alluring as ever. (Source and quotes: Homosexualities, by Stephen O. Murray, University of Chicago Press, 2002, p. 174) |

|

The shaving of the forelock may not have been such a sudden act for a boy of 15 or 16. In the introduction to the The Great Mirror of Male Love (Stanford University Press, 1990, p. 29) Paul Gordon Schalow tells us "At the age of eleven or twelve the crown of the male child's head was shaved, symbolizing the first three steps toward adulthood. The shaved crown drew attention to the forelocks (maegami), the boys distinguishing feature. At the age of fourteen or fifteen the boy's natural hairline was reshaped by shaving the temples into right angles, but the forelocks remained as sumi-maegami (cornered forelocks). This process, called 'putting in corners' (kado o ireru), was the second step towards adulthood. From being a maegami (boy with forelocks), the wakashu had now graduated to being a sumi-maegami (boy with cornered forelocks). The final step, completed at age eighteen or nineteen, involved cutting off the forelocks completely; the pate of his head was shaved smooth, leaving only the sidelocks (bin). Once he had changed to a robe with rounded sleeves, the boy was recognized as an adult man (yarō). He was no longer available as a wakashu for sexual relations with adult men like himself but was now qualified to establish a relationship with a wakashu."

Schalow addresses the historical issues of sexuality and the cutting of the forelocks on pages 35-36: "Much to the chagrin of the authorities, kabuki next became a vehicle for displaying the charms of beautiful boys, whether as wakashugata or as onnagata. During the reign of the third Tokugawa shogun, Iemitsu, the social problems produced by this situation were not addressed, possibly because he was known as something of a connoisseur of boys himself. Within a year after his death in 1651, boys were finally banned from the stage, first in Edo and then in Osaka and Kyōto. Theater proprietors negotiated with the authorities and were eventually allowed to reopen the theaters under certain stipulations: the name kabuki was forbidden, and the name 'Mime Theatrical Show' (monomane kyōgen zukushi) replaced it; actors were told to reduce eroticism and increase the realism and dramatic quality of their roles; and perhaps most important, boy actors were required to shave off their forelocks in the manner of adult men (yarō)."

Above is the cover to the paperback edition of The Great Mirror of Male Love written by Ihara Saikaku. In it are numerous references to older men smitten with young boys and either waxing poetically about or pining for one more view of the young boys' forelocks.

Saikaku in Kichiya Riding a Horse mentioned a fight among samurai which broke out over a young boy. Schalow tells us that was in the 6th month of 1652 and led to the rule about shaving forelocks. Saikaku wrote: "Theater proprietors and the boys' managers alike were upset by the effect it might have on business, but looking back on it now the law was probably the best thing that ever happened to them. It used to be that no matter how splendid the boy, it was impossible for him to keep his forelocks and to take on patrons beyond the age of twenty. Now since everyone wore the hairstyle of adult men, it was still possible at age 34 or 35 for youthful-looking actors to get under a man's robe. How strange are the ways of love!"

"Hair was in fact believed to provide a direct connection to the gods. For example, the forelock on children was left uncut because it was believed that this is what the gods would yank on if the children were in trouble." Quoted from: Asian Material Culture, essay by Martha Chaiklin, p. 41. |

||

|

|

||

|

Magaki |

籬

まがき |

A latticework. In the Yoshiwara or red-light district "There were three classes of bordellos..." The houses with the highest class of prostitutes had a latticework which was the largest, most expansive, running from near the floor all the way to the ceiling. This was referred to as the ōmagaki or sōmagaki, i.e., the large or complete lattice. Medium sized houses had lattices which which only covered 3/4th of the space of the ōmagaki. These were called han-magaki or majiri-magaki (a half or mixed lattice). The lowest class houses which never offered the highest rank of courtesans had a half lattice, i.e., the bottom was latticed and the top half was open. These were called so-han-magaki or 'complete half-lattice'. (Source: Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan, by Cecilia Segawa Seigle, University of Hawaii Press, 1993, pp. 234-5)

A magaki can also be a fence or hedge as can seen in the image below. 1

See also our entry on kōshi on our Kogai thru Kuruma index/glossary page. |

|

Magatama |

勾玉 or 曲玉

まがたま |

Comma-shaped jewels

The magatama seen above are from the 4th century. They were found at an archeological dig and are now in the collection of the Tokyo National Museum.

The images to the left are from the same Kofun period and are in the same collection. |

|

Curved or comma-shaped stone beads known as magatama (勾玉/曲玉) are often considered to have been used as amulets, talismans, or ritual items in ancient Japan. They are connected with beliefs in the magical power of various symbolically represented animals and the celestial world, the moon, or the soul and spirit. Throughout the Jōmon period, magatama were embedded within common household objects and tools as well as ritual items and they were used, lost, or discarded within houses. The specific functions and meanings of the magatama found in Jōmon houses are not clear, but these beads were consistently present for thousands of years in everyday settings where daily household activities were carried out. In Late Jōmon, however, some magatama beads were included in grave goods in northern Japan (Tōhoku and Hokkaidō). This transformation in their role occasionally spread to central parts of the main island of Japan, such as Hokuriku and Kantō. Other bead types made of talc or jadeite had already been buried in tombs since Early Jōmon, but it was not until Late Jōmon that magatama became regularly buried in tombs, apparently being worn by or given to the deceased at the time of entombment. The dramatic increase in the production of these small curved stone beads and their deployment in clusters of grave pits in cemeteries suggest that this was a personalization process leading to more individualized ownership of the magatama. After Late Jōmon, much smaller and more varied magatama shapes began to occur in graves along with other personal items such as combs, pendants, and earrings. The increased production and individual ownership of these body ornaments suggest that the Jōmon people enjoyed relative material comfort in northern Japan.

Above is the abstract for 'The Evolution of Curved Beads (Magatama 勾玉/曲玉) in Jōmon Period Japan and the Development of Individual Ownership' by Yoko Nishimura.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Mage |

髷 まげ |

Topknot - "The usual wig for male characters consists of a back hair section and side-locks that are dragged back and tied into a forward-facing topknot (mage)." Quoted from: A Guide to the Japanese Stage: From Traditional to Cutting Edge by Cavaye, Griffith and Senda, p. 75.

"...signs of dishevelment to the topknot or sidelocks are usual indications of mental distraction or of a rather disreputable character." (Ibid.) |

|

Makai |

魔界 まかい |

Realm of demons, world of spirits, hell. |

|

|

巻 まき |

Volume (of a book) |

|

Makimono |

巻物

まきもの

|

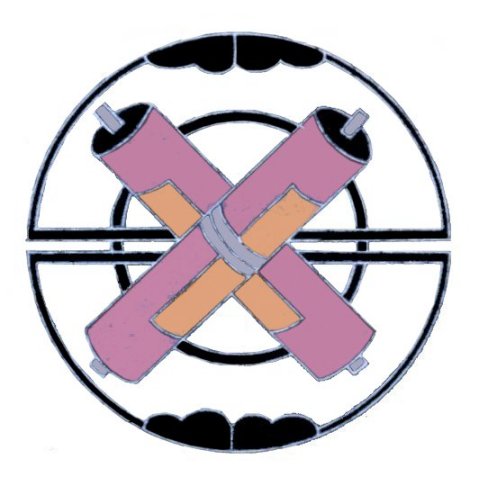

Scrolls: When shown in pairs they are one of the symbolic lucky treasures. They are often displayed crossed.

The image to the left on top is similar to one shown in John Dower's book on Japanese crests or mon. However, Dower lists it under a section on amulets and notes that it was used by a branch of the Ikeda family from Bizen province who remained 'hidden Christians' after the outlawing of Christianity. This design was chosen not because of its well known connection with Buddhism, but because it contained a hidden cross motif. The image shown below that is shown in its more traditional form as one of the lucky treasures. (See the first graphic entry on manji below.) Source: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, published by Weatherhill, 1991 edition, p. 102. |

|

Makura |

枕 まくら |

Pillow - In Back and Bed: Ergonomic Aspects of Sleeping by Bart Haex from 2004 it says "The traditional Japanese pillow (makura), for example, is filled with red beans, or buckwheat chaff." |

|

"In Far Eastern countries the pillow was generally made of solid wood, and, for use in the summer, of ceramics, covered with a small bag containing tiny seeds, etc. The wooden pillow often contained a drawer or opening in which amulets were kept. In Japan during the Tokugawa period, the daimyō' s pillow was often a lacquered box having a slightly curved upper surface perforated with ornamental designs. Through these was emitted smoke of burning incense stored within, to ensure redolent slumber for the daimyō." Quote from: The Trail of Time: Time Measurement with Incense in East Asia by Silvio Bedini, 1994, fn. 17, p. 132.

"...in this cupboard the guests sometimes find the sleeping blocks that serve the locals as pillows for their heads. The blocks are shaped like a cube, are hollow, and are made of six thin boards joined together. They are varnished on the outside, smooth and clean, not much longer than one span, while their width and depth is somewhat less, so that turning them in various ways one's head may be higher or lower. The traveler cannot expect any further bedding from his host. Those who do not carn their own bedding use the mat-covered floor as a mattress, their coat as a blanket, and this hollow block of wood as a pillow." Quoted from: Kaempfer's Japan: Tokugawa Culture Observed, 1999, p. 264. Kaempfer's book was first published in 1727.

"Stacked beside the futon were the soba gara makura (soh-bah gahrah mah-koo-rah). These small pillows, designed a thousand years ago, were filled not with the feathers from suddenly naked, shivering geese, but of all things, with the hulls of buckwheat! They were about as far from our fluffy, cushy Western headrests as a pillow could be without being a chunk of wood. After a rough day at work it was at first difficult to be lulled into dreamland by these pillows. Rather, yoursleepy senses were convolutedly shocked awake. In particular, your delicate hearing. As the weight of your head pressed into the pillow, a bejillion tiny buckwheat hulls—sounding up close more like their cousins, the harder and tougher peppercorns—began combatively shifting in a noisy, grinding grating crunch until their jostling finally gave up on the pecking order and settled into place. This place turned out to be the perfect contour of your head. ¶ If you lay your head cheek-down upon this container of grit with one of your finely-tuned ears (whose ability to hear had now, without warning, magnified because of its close proximity to all the racket) it sounded uncannily like the explosions under automobile tires as they drove over a bountiful fall harvest of plump acorns spread across a cement driveway. The ensuing, seemingly endless eruptions continued until all the hulls had at last come to their raspy resting places—the exact imprint of your now wide awake profile." |

||

|

|

||

|

Makura kotoba |

枕詞 or 枕言葉 まくらことば |

Pillow word - "...a fixed epithet placed before the names of provinces, mountains, and certain other nouns, and perhaps intended originally to invoke the magic of a place by mentioning its special attribute — its title, as it were. It is rather like the epithets found in Homer, such as 'ox-eyed Hera' or 'fleet-footed Achilles,' used even when the eyes or feet of the person are not in question." Quoted from: The Pleasures of Japanese Literature by Donald Keene, pp. 26-27. |

|

Makura sōshi |

枕草子 まくらそうし |

"Pillow book" - "The meaning of 'pillow book' (makura sōshi) is uncertain, but the term is commonly thought to have designated some kind of notebook. A sōshi ("book") was a stitched fascicule of paper, often with leaves in a variety of colors." Quoted from: A Tale of Flowering Fortunes by Helen Craig McCullough, volume 1, 1980, p. 651. |

|

Makyō |

魔鏡 まきょう |

An ancient Chinese mirror making technique adopted by the Japanese in which a hidden image appears in certain lighting. |

|

Maneki neko |

招き猫

まねき.ねこ |

Beckoning cat: When the wearing of earrings became more popular among young men a number of years ago I was incredibly naive. I still am, but now I know that there was a coding system at that time as to which ear it is worn in. Quickly I was taught the anti-gay mantra of "Right is wrong and left is right". And no I am not anti-gay, buy that is the saying. I mention this because there seems to be a lot of discussion out there as to the significance of which paw the beckoning cat has raised. Mock Joya says that there is "...a popular tradition that when a cat passses [sic] its left paw over its left ear it is a sign that visitors will come." It must be true because these creatures are ubiquitous. They come in ceramic, wood, bronze and other forms. They show up in shops and restaurants everywhere. Sometimes the businesses are owned by Japanese, but one is just as likely to run into them in Chinese, Korean or even Waspish establishments.

One story about its origin: There was a famous Yoshiwara courtesan who had a pet cat. As the woman was entertaining a client the cat kept pawing at her and would not go away. Irritated the client drew his sword and beheaded the cat. Its head flew up toward the rafters and it killed a snake which was about to strike the courtesan.

Grief stricken the courtesan gave it an elaborate burial and erected a tombstone. Then she asked a sculptor to recreate the cat in all its features. When done it showed the cat with a left paw raised to its ear. She caressed and fed it - or tried to - everyday. And this was the first maneki neko. (Source and quote: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 110)

The image to the left was created by David Wilcox especially for this site. Thanks David! |

|

"Always in the dwelling which a band of geisha occupy there is a strange image placed in the alcove. Sometimes it is of clay, rarely of gold, most commonly of porcelain. It is reverenced: offerings are made to it, sweetmeats and rice bread and wine; incense smoulders in front of it, and a lamp is burned before it. It is the image of a kitten erect, one paw outstretched as if inviting--whence its name, 'the Beckoning Kitten.' It is the genius loci: it brings good-fortune, the patronage of the rich, the favour of banquet-givers. Now, they who know the soul of the geisha aver that the semblance of the image is the semblance of herself--playful and pretty, soft and young, lithe and caressing, and cruel as a devouring fire." (Quoted from: Glimpses of an Unfamiliar Japan by Lafcadio Hearn) |

||

|

|

||

|

Manji |

萬治 or 万治

まんじ |

The reign period from 1658-1661. This era "...though brief, forms a key point in the development of ukiyo-e. For it was during this period that in Edo (reconstructed after the Meireki Fire of early 1657), the first illustrations and prints in fully developed ukiyo-e style appeared, these being the work of that anonymous artist we call the 'Kambun Master'. Manji marks, for that matter, a minor peak both in Kyoto and Edo illustration, and many of the masterpieces of early Japanese book illustraton date from this brief period." Quoted from: "Historical Eras in Ukiyo-e" by Richard Lane in Ukiyo-e Studies and Pleasures, Society for Japanese Arts and Crafts, the Hague, 1978, p. 28.

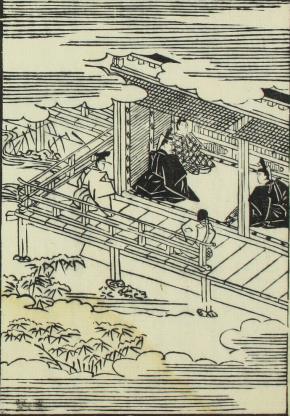

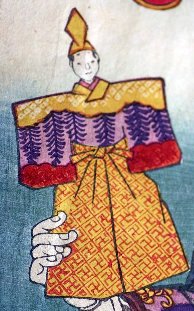

The image to the left is an illustration from 1660 from the Utsuho monogatari from the collection at the Waseda University Library. |

|

Manji |

万字

まんじ

|

The swastika which has its origins in Indo-Aryan design and was adopted as a positive Buddhist symbol of happiness and well-being. In China it came to mean 10,000 or longevity, even eternity. "In Zen it symbolizes the 'seal of buddha-mind'..." (Quoted from: The Shambala Dictionary of Buddhism and Zen, p. 214)

See also our entry for sayagata.

A personal note: If I have heard it once I have heard it a thousand times that the arms of the Asian swastika go a different direction from that of the Nazi swastika. As best I can tell this is untrue. The Asian swastika was so often incorporated into decorative schemes that it can be found going both ways in the same design. It would seem that people insist that there is a distinct and noticeable difference between the swastika as it was used by the Asians and by that of the Germans because they are trying to exonerate the original source. However, this is really no more realistic than your run of the mill urban myth.

The word 'swastika' is of Sanskrit origin and was meant to convey a concept of well-being, fortune or luck. Among certain Tibetan groups this symbol was always shown rotating counterclockwise... "unlike the Hindu, Jain and Buddhist swastika, whose sacred motion is clockwise." (Source and quote: The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs, by Robert Beer, published by Shambala, 1999, p. 344)

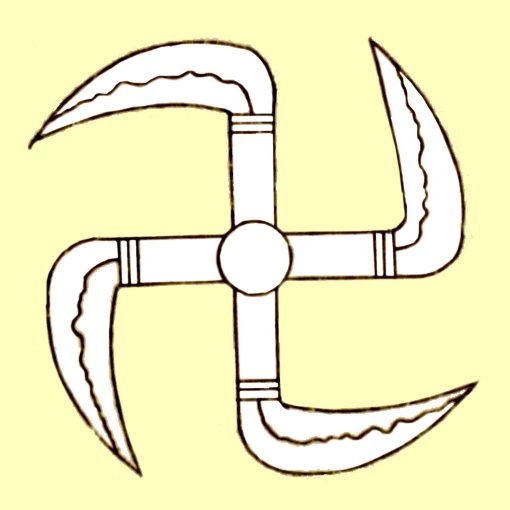

The image to the left is a detail from a Kuniyoshi print.

To the left above the sickle, kama (鎌), crest or mon functions on various levels. As a sickle it is associated with a protective deity which cuts down its enemies. Combined into a swastika form would simply magnify its efficacy.

Anyone who has studied ukiyo-e long enough will know that the manji is used frequently, almost ubiquitously, over a period of decades. Ordinarily it appears in the most subtle forms on the under-robes - generally in blue and white patterns which are interlaced - being worn by some of the figures. Because of its positive connotations it is rarely seen on the clothing of villains as it is here.

Below is an example by Kunitsuna where the blue and white swastika design is clearly shown. To the left we have isolated a part of the design for easier viewing.

|

|

Manji tsunagi |

万字繋 or 卍繋 まんじつなぎ |

The interlocked swastika motif. The term tsunagi refers to any number of motifs which are interlinked, like .

The detail to the left comes from a print in the Lyon Collection. Click on the image to see the full print. |

|

Man'yōgana |

万葉仮名 まんようがな |

"Man'yōgana are a set of unmodified Chinese characters that were once used as phonetic symbols to represent Japanese syllables. As the name suggests, man'yōgana (manyo + kana) was the writing system used in the Man'yoshu, an 8th century anthology containing poems from the 5th century to 759 AD. Most attempts to write Japanese prior to the Heian period (794-1185) fall into the category of man'yōgana. Thereafter man'yōgana gives way to other forms of kana." These characters were written "...without modification or simplification." Since they represented only sounds they might look like a traditional Chinese text but would be completely unreadable nonsensical to a Chinese reader. (Source and quotes from: the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 4, p 131, entry by Haruo Aoki) |

|

Man'yōshū |

万葉集 まんようしゅう |

Japan's oldest poetry anthology dating from the 8th century. Donald Keene in his Seeds in the Heart: Japanese Literature from Earliest Times to the Late Sixteenth Century (Henry Holt and Company, 1993, p. 3) says: "Japanese poetry did not begin with the Kokinshū. Indeed, it is generally accepted that many of the finest poems of the language are found in the Man'yōshū, a collection compiled well over a century earlier; but the secret of how to read the complicated script in which the poems of the Man'yōshū were transcribed was not unlocked until the seventeeth century, and during the nine hundred years after the completion of the Man'yōshū, poets looked back to the Kokinshū as the finest flowering of court poetry, a model that they sought to emulate in language, subjects and above all its typical form, the waka."

"The myth of Japan's creation tells less of the islands' physical formation than their ritual creation. Myths contained in the Kojiki (the earliest Japanese history, compiled in 712) and the Nihon Shoki (a history of Japan compiled in 720) were probably mythical accounts of ancient rituals, especially imperial ones. It is likely too that the Man'yōshū (a collection of ancient poems compiled in the mid-eighth century) was meant to record ritual language, in the form of songs used in a variety of rituals and ritual occasions and which were subjected to ritual protocol." Quoted from: Chaos and Cosmos: Ritual in Early and Medieval Japanese Literature by Herbert Plutschow, p. 3. |

|

Marumage |

丸髷

まるまげ |

"...lit. a round chignon. the marumage hairstyle, a traditional coiffure developed during the Edo period (1603-1868). The style is made up of an elevated oval-shaped chignon, a small front tuft, and puffed-out back and side locks. It was widely worn by married women until the end of the Meiji era (1868-1912).

Quote from: Dictionary of Japanese Culture by Setsuko Kojima and Gene A. Crane, p. 203. |

|

|

||

|

Maru ni mitsu kashiwa |

丸に三つ柏

まるにみつかしわ

|

A samurai family crest of three oak leaves in a circle. It has been said that when food was offered to the Imperial family on special occasions it was often placed on oak leaves, a platter worthy of the gods. This motif may also have been used or licensed for commercial establishments because it appears as part of the designs of certain Japanese woodblock prints by Utamaro, Shunchō and Eisen and probably others.

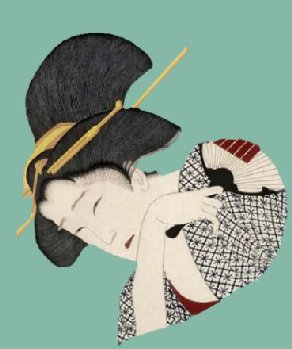

All of the images are from the collection of the British Museum. Both prints represent Ohisa, a great beauty whose father owned a teahouse. The image to the left is by Shunchō and the one above is by Utamaro from ca. 1793. |

|

Matsu |

松

まつ

|

Pine tree - a symbol of longevity, winter and New Years and being virtuous.

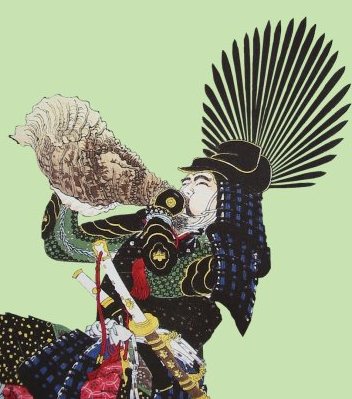

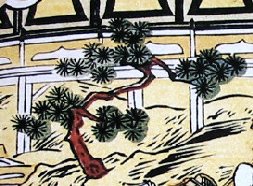

The image to the left on top is a detail from a Toyokuni I print showing a painted backdrop.

Being green throughout the year, resistant to strong winds and heavy snows the pine came to symbolize longevity. Several families adopted a variation on the pine motif for use as their family crest. |

|

Matsuba |

松葉

まつば |

Pine needle(s): These were "...were used to express one's sincerity and sentiments in presenting gifts to others." (Quoted from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p.364)

Above is a photo of Portuguese pine needles posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Tintazul.

In a prominent Kyoto restaurant one dish is called matsuba sōmen or green tea noodle fans. It is described as "Fans of thin noodles, deep-fried to resemble pine needle sprays."

In some cases real green pine needles are used as skewers for food much in the same way people in the West use toothpicks.

The International Dictionary of Food and Cooking describes a particular display of splayed cucumber as matsuba because it is reminiscent of pine needles.

Mushi-garei (蒸鰈) is steamed flatfish which is cooked with pine needles at the beach.

The image to the left is shown courtesy of Shu Suehiro http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. |

|

Masaoka Shiki (正岡子規: 1867-1902) wrote a thoughtful and evocative poem in 1898 - as translated by Burton Watson:

Gusts of winter wind- pine needles strewn all over the outdoor Noh stage

In a discussion of tattooing techniques in Irezumi: the Pattern of Dermatography in Japan by Willem R. van Gulik (p. 100) lists matsuba-mikiri (松葉みきり) or a pine-needle border of "...closely spaced short vertical straight lines."

One of the houses of prostitution in the Yoshiwara district of Edo was the Matsuba-ya or House of Pine Needles. Courtesans from this establishment were illustrated by Choki, Eishi, Utamaro and Kunisada. Below is a print of the courtesan Ichiwa of Matasuba-ya by Utamaro. It is in the collection of the Cincinnati Art Museum. Notice that the background pattern is the pine bark motif (see matsukawa-bishi further down this page):

An age-matsuba (上げ松葉) is a teahouse in a garden where pine needles carpet the ground to keep it and the moss from freezing in winter. It is said that "...Furuta Oribe [古田織部: 1545-1615] devised this technique. These strewn matsuba are picked up (ageru, age) little by little from New Year's Day in the lunar calendar starting with those closer to the teahouse until they are completely removed." (Source and quote from: Chado: The Way of Tea, p. 105) A poem by Fuhaku (不白: 1716-1807) from the same book goes: The day when the bush warbler starts singing is the day pine needles are picked up. |

||

|

|

||

|

Matsubame-mono |

松羽目物 まつばめもの |

Kabuki plays adapted from Noh theater 1 |

|

Matsukawa-bishi |

松皮菱

まつかわびし

|

Pine bark lozenge motif

|

|

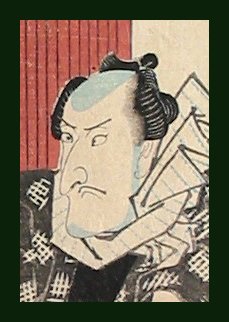

Matsumoto Kōshirō V |

(五世)松本幸四郎

(ごせ)まつもと.こうしろう |

|

|

Matsuri |

祭り まつり |

Festivals |

|

Scott Schnell in the Rousing Drum: Ritual Practice in a Japanese Community (University of Hawaii Press, 1999, p. 290) tells us exactly what the purpose of a matsuri is. "The matsuri has been used at various times by its participants to commune with the supernatural, establish or strengthen interpersonal relations, generate and preserve a sense of collective identity, garner prestige, further political ambitions, assert or reaffirm the authority of the local elite and/or the state, challenge that authority, seek retribution for perceived injustices, relieve tensions through cathartic expenditure of energy, settle old scores, and stimulate economic development."

Gloria Ganz Gonick in her Matsuri! Japanese Festival Arts (published by the Fowler Museum, UCLA, 2002, p. 24) adds to what Schnell says: "The essence of matsuri is a prescribed sequence of religious rites held for a group and led by a Shinto priest. The original impetus for establishing a matsuri was usually a felt need to commemorate a historic event of local significance or to seek a fortuitous change in the economic or agricultural outlook of a community. To accomplish this, it was deemed necessary to directly interact with the Japanese deities (kami) and beseech their cooperation." ¶ These festivals "...may include a lively costumed pageant, promenading band, adn semiprofessional dance troops, as well as abundant feasting and drinking." All of this originally has a religious basis, but today such gatherings are increasingly secular. ¶ "Matsuri are hosted by a particular Shinto shrine (jinja) of one community and organized by its neighborhood association (chōnai-kai)." For that reason each matsuri has it own local flavor.

See also our entry on yamaboko or festival float on our Ya thru Z index/glossary page.

"All matsuri make deities visible in one way or another." Quoted from: Matsuri: The Festivals of Japan... by Herbert Plutschow, p. 2. |

||

|

|

||

|

Mawari-dōrō |

回燈籠

まわりどうろう |

Magic lantern -

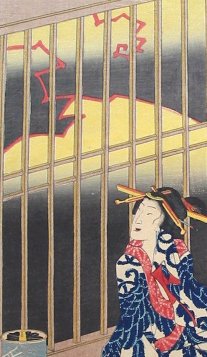

We found the image to the left, dating from before 1936, at Pinterest. It is by Shotei (aka Hiroaki - 1871-1945) and comes from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. The Okumura Toshinobu from the 1720s seen below is from the collection of the MFA in Boston. It, too, was posted at Pinterest.

Mawari-dōrō were "Introduced from China... [They] were popular during the Edo period (1600-1868) for viewing on summer nights. The lantern consists of a cylinder pasted over with paper silhouettes and placed inside a circular frame covered with thin paper or cloth; heated air from a lighted candle in the center of the cylinder causes this to revolve and produce moving images on the translucent outer covering." Quoted from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, Volume 5, entry by Saitō Ryōsuke, p. 142. |

|

Timothy Clark wrote about this print that it shows a courtesan lounging on a hot early autumn day. She is "...admiring the shadow show on the rotating mechanical lantern (mawari-dōrō) beside her, which shows the retinue of a grand courtesan (oiran dōchū) in procession beneath a large parasol. The winding path amid reeds along the bottom of the lantern must represent Nihon-tsutsumi (Japan Embankment), the route to the Yoshiwara pleasure quarter. Hanging behind her to the left of the reed blind is a large decorative bon lantern (bon-dōrō) for the ura-bon festival, hled in veneration of dead ancestors around the fifteenth day of the seventh month. ¶ Prominent on the courtesan's sleeve is a crest of combined wisteria and water plantain (fuji-omodaka). Not the crest of a kabuki actor, it is probably the personal crest of the courtesan. This is thus a genre scene, not a theatrical print. The character shinobu written on the courtesan's fan may be her name." Quoted from: The Dawn of the Floating World p. 269. |

||

|

LINKS TO OUR OTHER INDEX/GLOSSARY PAGES Click on any of the pages listed below!

|

||

HOME

HOME