Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

Tomoe thru Tsuzumi |

|

|

|

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Tomo-e, Tōmyō, Tōmyōdai, Tonda chagama, Torii, Torimono, Tori no ichi, Tori no matsuri, Torite, Tōrōbin, Toshidama, Toshikoshi soba, Toshi otoko, Tōuchiwa, Toyohara Kunichika, Tōyōrin jigoku, Tsuba, Tsubaki, Tsubone mise, Tsuchigumo, Tsuchi mon, Tsuitate, Tsuji-gimi, Tsuka, Tsuka, Tsukimi, Tsukioka Yoshitoshi, Tsukubai, Tsukumo-gami, Tsuma, Tsumugi, Tsuno, Tsunokakushi, Tsurezugegusa, Tsuru, Tsuru, Tsuru-bishi, Tsurugi, Tsurukusa, Tsuruya Kokei, Tsuruya Namboku V, Tsūshō, Tsuyukusa and Tsuzumi

巴, 灯明, 灯明台, とんだ茶釜, 鳥居, 採物, 酉の市, 酉の祭, 捕り手 or 捕手 燈籠鬢, 年玉, 年越蕎麦, 年男, 唐団扇, 豊原国周, 刀葉林地 獄, 鍔, 椿, 局見世, 土蜘, 槌紋, 衝立, 辻君, 柄, 塚, 月見, 月岡芳年, 蹲い, 付喪神, 妻, 紬, 角, 角隠し, 徒然草, 吊り枝, 鶴, 弦, 鶴菱, 剣, 蔓草, 弦屋光渓, 鶴屋南北, 艶墨, 通称, 露草, 鼓 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the light green numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Tomo-e |

巴

ともえ

|

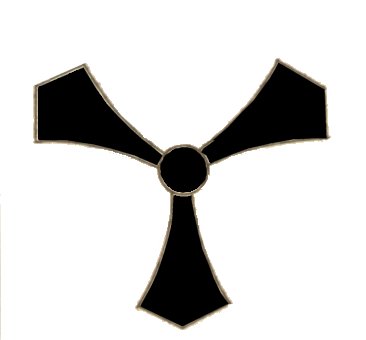

The origin of this motif is obscure and unknowable. Was it borrowed from another culture or did it spring up independently? Some forms seem a little to simple not to have occurred to different peoples in different times. Translated by several sources as a 'huge comma design'. Dower says Yorisuke Numata, an expert on Japanese heraldry "...emerged...as a design...being a picture (e) of a leather guard worn on the left wrist by archers to receive the impact of the bowstring after it had been released..." In fact the wrist guard is called a tomo but is written with a differnt character altogether, 鞆. (Source and quote: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 145)

The use of color is my own. If I have broken some kind of taboo I apologize. Just let me know.

"Tile fragments excavated from the site of Oda Nobunaga's Azuchi Castle, constructed 1576-1579, include eave-edge tiles with tornoe 巴, or comma, motif antefixes inlaid with gold." [An antefix is a "carved ornament at the eaves of a tile roof concealing the joints between tiles".] (Quoted from: "Edo Architecture and Tokugawa Law", by William H. Coaldrake, Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 36, No. 3. (Autumn, 1981), footnote 55, p. 255)

Gold inlay on eaves and ridge tiles was a typical feature of Momoyama and early Edo-period architecture, used as a means of enhancing the splendor of buildings by highlighting the profile of the roof." (Ibid.)

A tomo-e with two commas is called a "futatsu-tomoe" while one

with three is a "mitsu

tomoe".

|

|

Tōmyō |

灯明 とうみょう |

A light offered to a god or Buddha; a votive light. |

|

Tōmyōdai |

灯明台

とうみょうだい |

Literally a stand for the light offered to the gods or Buddha. A special type of temple lighting. Hepburn defined this as a 'light-house'. Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary from 1931 gives both definitions as acceptable.

The photo to the left was posted at commons.wikimedia by Kansai explorer. The one below which appears to decorate a ceramic plaque was placed at Pinterest by Hitomi Fujiwara.

|

|

Tonda chagama |

とんだ茶釜 |

The flying teakettle ceremony: Because of punning words plays the flying teakettle became an allusion to a sexually attractive woman. "...Ota Nampo relates a saying current in Edo about the second month of 1770: 'The tea ceremony kettle flew away and turned into a common teakettle' (Tonda chagama ga yakan nito baketa)." This may have been a reference to the elopement of Osen, a great teahouse beauty, who left her father to run his business without her. (Quoted from: The Actor's Image: Print Makers of the Katsukawa School, Timothy Clark, Osamu Ueda and Donald Jenkins, Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 78)

The image to the left is a detail from a Bunchō print from ca. 1770. |

|

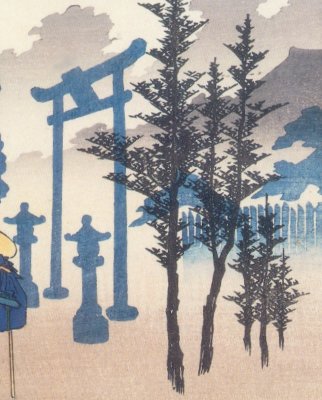

Torii |

鳥居

とりい

|

The Shinto shrine archway found at the entrance. Torii is one of those words which has entered the English language as is. There are words which you might look up in a dictionary and you find the word itself in the definition. Well, torii is one of those words.

In one of the best known early myths is the story of Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess, who shut herself up within a cave depriving the world of light. "...a cock sat outside crowing for her to come forth. According to some scholars, the distinctive Shinto gateway represents the perch on which the cock sat, while the straw rope often strung across the gateway was used to keep the goddess from reentering the cave once she had been enticed forth... The ideographs with which torii is written literally mean 'bird reside,' which seems to lend etymological support to this theory."

Source and quote from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 124. |

|

Torimono |

採物 とりもの |

"Things held. Items borne in the hand by performers of kagura and by shinshoku and miko in shrine performances, possession of which indicates that the holder is a suitable channel for communication with the kami. There are traditionally nine tori-mono: the sakaki sacred branch, the mitegura (cloth offering), the tsue (staff), sasa (bamboo grass), yumi (bow), tsurugi (sword), hoko (halberd), hisago (gourd) and kazura (vine)." (Quoted from: A Popular Dictionary of Shinto by Brian Bocking, p. 208.) |

|

Tori no ichi |

酉の市

とりのいち

|

"An annual fair held at Ōtori shrines during November on the days of the cock (one of the 12 signs of the zodiac.)" These shrines "...are dedicated to Yamato Takeru no Mikoto, a deity of war; today the shrines are worshiped by merchants praying for good fortune. The chief feature of the fair is the sale of bamboo rakes decorated with good-luck symbols: ornaments representing gold coins, cranes and tortoises, pine trees, figures of the Seven Gods of Good Fortune...etc. The rakes are believed to rake in good fortune." (Source and quotes: Dictionary Japanese Culture, by Setsuko Kojima and Gene A. Crane, Heian International, Inc., 1991, p. 364.)

Yamato Takeru no Mikoto is one of the gods mentioned in the Kojiki (古事記: 712), Japanese oldest work of written literature.

The rakes sold at the shrines are called kumade (熊手). Mock Joya says that "Once you buy kunmade you have to buy it every year to ensure your good fortune. Not only this, but the kumade you get must be larger every year." This was a practice started by merchants in the Edo region. Since it was unseemly for members of the samurai class to purchase such items they sent others to do it for them.

The tori no ichi celebrations take place at least twice every November, but sometimes three 'cock days' can fall within a month. Having three such propitious days meant that there would be greater prosperity, but also a greater number of fires "...because prosperity makes the people careless." (Source and quotes: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 402-3)

Kumade, the Japanese word for rake, is made up of two characters meaning 'bear' and 'hand' - 熊 and 手.

The two detailed images to the left and below are from a print by Toyokuni III showing a fellow carrying a decorated kumade in a procession wending its way to an Ōtori shrine.

|

|

Tori no matsuri |

酉の祭 とりのまつり |

Also referred to as tori no machi (酉の待・酉の町). "The Tori-no-Matsuri, or Fęte of the Cock, is celebrated on the cock days in November... As a rule, on those fęte days all the prostitute-quarters open every gate and receive the visitors, who also see the occasion to see their loving objects - beautifully dressed harlots." (Quoted from: The Yoshiwara From Within)

On this day all access routes into the Yoshiwara district were thrown open and anyone of either sex could enter freely. This was known as a monbi (紋日) or holiday when each prostitute was expected to take a customer or at least pay a fee as though they had generated the same amount of income. |

|

Torite |

捕り手 or 捕手

とりて |

Archaic term for a policeman; official in charge of imprisoning offenders - Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary defines it as "a raiding constable".

The image to the left is from 1822 and is by Hokushū. It is a left-hand panel of a triptych. It shows the actor Ichikawa Ebijūrō I as a torite. |

|

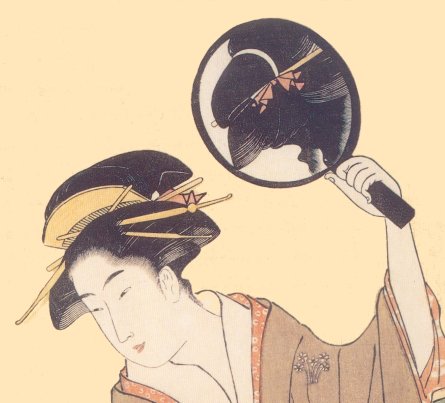

Tōrōbin |

燈籠鬢酉の

とうろうびん |

A hair style "...called lantern locks (tōrōbin), in which the side locks were combed outward to resemble the silhouette of a paper lantern, had just become the rage [in ca. 1775]."

Quote from: The Actor's Image: Print Makers of the Katsukawa School, Timothy Clark, Osamu Ueda and Donald Jenkins, Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 214.

This style of sweeping the hair back and out from the bottom of the ear originated in the Kansai district which includes the areas around Osaka and Kyōto. (Ibid., p. 229, fn. 2)

This style remained popular for decades and can often be seen in prints by Utamaro, Toyokuni I and others. This detail is from a print by Eishi. |

|

Toshidama |

年玉

としだま |

New Year's gift: For much more about this topic please go to our web log posting on the otoshidama at http://printsofjapan.wordpress.com/2009/06/02/otoshidama/.

To the left is a modern otoshidama posted at Wikimedia commons. |

|

Toshikoshi soba |

年越蕎麦

としこしそば |

"Year-crossing" soba 1 The length of the noodles seems to have a relationship with the wish for propsperity in the coming year. Some sources say it is to promote a long life and a smooth transition from one year to another. This is also part of the Shinto celebration of greeting the New Year.

"On New Year's Eve, soba (buckwheat noodles) is served in a clear broth. Soba served on the eve is called toshikoshi soba (year-crossing soba). It is said that long ago in Japan, goldsmiths and silversmiths used soba dough to collect scraps of gold and silver. Therefore, soba is associated with earning money and is eaten as a lucky charm ensuring a prosperous New Year. The noodles are also a symbol of longevity." Quoted from: Ethnic Foods of Hawaii by Ann Kondo Corum, p. 61.

Rick LaPointe in The Japan Times of December 30, 2001 stated that the practice of eating these noodles on New Year's Eve is at least 200 years old.

The image to the left was posted at Flick by Ted Kanakubo. We have trimmed it ever so slightly.

"As Yanagata (1970) observes, the Japanese normally conceived of a day from evening to evening rather than morning to morning, and so the first meal of the New Year is actually taken on New Year's Eve. The period before the meal is one of strict abstinence until the first sounds of the temple bell at eleven o'clock could be heard around the town. When they were younger, the children of the household had then paid their respects to their grandparents and received sweets in return called toshi dama. The family then ate a meal of Japanese noodles (toshikoshi soba)" and a large stew of the usual winter fare: potato-starch noodles, fried bean curd, eggs, tofu, daikon and shiitake mushroom flavouring." Quoted from: Ceremony and Symbolism in the Japanese Home by Michael Jeremy and Michael Ernest Robinson, 75. |

|

Toshi otoko |

年男 としおとこ |

Literally it means 'man of the year'. In a daimyō's abode it is the servant who is "...responsible for setting up the New Year pine tree decorations , drawing the first water of the year and arranging the offering to the god who ruled the year's lucky direcetion (toshitokujin)." Quoted from: Reading Surimono..., edited by John Carpenter, p. 374.

Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary defines this term as the one who scatters beans at the Setsubunritual. |

|

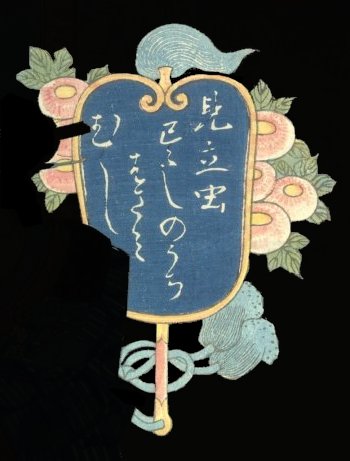

Tōuchiwa |

唐団扇

とううちわ |

A T'ang Dynasty fan shape. Very similar in shape to the gumbai (軍配) or war paddle which was also carried in sumo by the umpire.

The example to the left is from a print by Shigenobu.

Above is a detail from a print by Sadakage. To see this image in context click on his name. As yet we do not know what the text says. |

|

Toyohara Kunichika |

豊原国周 とよはらくにちか |

Artist 1835-1900 |

|

Tōyōrin jigoku |

刀葉林地 獄 とうようりんじごく |

Sword-leaf hell where a man driven by lust for a beautiful woman is condemned to jump up and down on a tree with leaves which are swords. |

|

Tsuba |

鍔

つば |

Sword guard. The hole in the center is referred to as a nakagoana (茎孔) because it holds the tang (茎) of the sword. Tsuba were generally made of steel, but other metals and alloys were used too. The tsuba prevents the users hand from slipping onto the blade and offers some protection in combat. "The weight of the guard also functions to bring the sword's center of gravity closer to the handle of the sword, adding 'balance' and force to a blow, and reducing fatigue to the wrist." The earliest known tsubas date from the Nara period (奈良時代) of 710-794.

Quoted from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 8, p. 108, entry by Walter Ames Compton. |

|

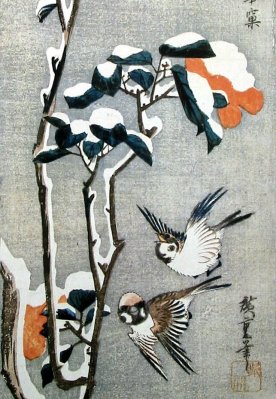

Tsubaki |

椿

つばき |

Camellia japonica: Lafcadio Hearn tells us that the Japanese "...believed in trees inhabited by malevolent beings,—goblin trees. Among other weird trees, the beautiful tsubaki (Camellia Japonica) was said to be an unlucky tree;—this was said, at least, of the red-flowering variety, the white-flowering kind having a better reputation and being prized as a rarity. The large fleshy crimson flowers have this curious habit: they detach themselves bodily from the stem, when they begin to fade; and they fall with an audible thud. To old Japanese fancy the falling of these heavy red flowers was like the falling of human heads under the sword; and the dull sound of their dropping was said to be like the thud made by a severed head striking the ground. Nevertheless the tsubaki seems to have been a favorite in Japanese gardens because of the beauty of its glossy foliage; and its flowers were used for the decoration of alcoves. But in samurai homes it was a rule never to place tsubaki-flowers in an alcove during war-time."

Hearn translated a poem as "When the night-storm is shaken the blood-crowned and ancient tsubaki-tree, then one by one fall the gory heads of the flowers, (with the sound of) hota-hota!"

|

|

A goblin tsubaki is known as a furu tsubaki (古椿)or "Old tsubaki". Young tsubaki start out innocent. These is true of other goblin trees like the willow and énoki, too.

The severed head seen above was contributed by Yoshitoshi. I added the pool of blood. The tsubaki flower is shown courtesy of the site run by Shu Suehiro http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. A site well worth visiting. This particular camellia is from the yabu tsubaki (藪椿).

Above is a detail from a Hiroshige print of sparrows and camellia in winter.

"The image of a camellia appears frequently in classical Japanese poetry. Although camellias bloom in different colors, it is the red camellia that has become part of the conventional hon'i ['the true purpose': 本意 or ほんい] of the poetic motif." (Quote from: Basho And The Dao: The Zhuangzi And The Transformation Of Haikai by Peipei Qui, pp. 57-8)

Above is another detail from a Hiroshige tsubaki print, but somewhat altered.

Tsubaki mochi (椿餅) are rice cakes filled with bean paste jam wrapped in camellia leaves. "Strained bean jam is wrapped up with dōmyōji [a rice pastry] and flattened for sandwiching between two leaves of tsubaki (camellia). This cake has a long history even going back to The Tale of Genji, where it appears in the chapter 'Wakana' as tsubai-mochihi. However, bean jam was not made in those days." (Quoted from Chado: The Way of Tea, p. 136) The elegant faint scent of tsubaki-mochi reminds one of the real things.

Royall Tyler in his brilliant translation of The Tale of Genji gives the setting for the eating of tsubaki mochi in chapter 34, 'Wakana' (vol. 2, p. 621): "The privy gentlemen had round mats put out for them on the veranda. Camellia cakes, nashi, tangerines, and other such things then appeared quite informally mixed together in box lids, and the young men ate them merrily. Then there was wine, accompanied by the appropriate dried seafood." Tyler then gave an extremely informative footnote: "Camellia cakes (tsubaimochii) were normally served after a kickball game. Cakes of powdered glutinous rice and powdered cloves, sweetened with syrup from the amachazuru vine, were wrapped in camellia leaves. The fruit known as nashi is round and crisp like an apple but in color and taste more like a pear."

These photos are also posted at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm.

In Joseph Dautremer's The Japanese Empire and Its Economic Conditions from 1910 describes the tsubaki: "It clothes the Japanese hills, and it often obtains a height of 33 feet. Its wood is hard and used in carpentering. The berries are used for the making of oil, with which the women freely plaster their hair." Robin Gill translated and commented on the writings of Luís Fróis said in Topsy-turvy 1585. Fróis referring to hair: "Japanese women go around reeking of the oil with which it is anointed." Gill: "European women who rarely bathed smelled good thanks to perfume., while Japanese women who bathed regularly stunk of oil. I doubt, however, that noblewomen reeked. I do not know if cloves - worth their weight in gold - were still added to their hair oil, i.e., mizu-abura, (literally 'water-oil') were still used in the sixteenth-century, as they were hundreds of years earlier, but Okada cites a work of literature where a woman is advised to trade in her sesame oil for the less smelly walnut oil if she would get into the good graces of her master, and this suggests to me that not all women smelled. I suspect also that this was a period when more and more common folk began to copy upper-class hair-styles that required oil. As few could afford the best oils, they had to settle for the somewhat cloying camellia (tsubaki), itself not cheap, or the pungent sesame (these oils, like olive smell wonderful fresh but turn smelly almost immediately in contact with the body). But it is a fact that smells are a very subjective matter." (pp. 144-45)

Constantine N. Vaporis in his article "Samurai and the World of Goods: the Diaries of the Toyama Family of Hachinohe" notes that "...the Toyama household purchased hair oil (binzuke) in Hachinohe for everyday use, but acquired more high-quality types, scented tsubaki abura [椿油] and oil for dyeing hair black (kuro abura) in Edo." Binzuke is 鬢付け油.

"The vegetable oil used in the old Japanese lamps used to be obtained from the nuts of the tsubaki." (Lafcadio Hearn) Just for contrast we are adding a quote from Heian Japan, Centers and Peripheries (p. 317) "The provinces generally pressed oil from sesame seeds, perilla seeds, hemp seeds, walnuts (kurumi), viburnum (hemi, yabudemari), camellia (tsubaki), and an unidentified plant called hosoki. Sesame and hosoki oils were the main lamp fuels, and all oils were used in the court's kitchens."

In Mansfeld's Encyclopedia of Agricultural and Horticultural Crops it states on page 1338 that the tsubaki was "Cultivated as an oil crop and ornamental. Seeds contain an oleic-rich, non-drying oil, which is used as watchmaker-, hair-, and vegetable oil, and also medicinally. In the past it was used as an antirust agent for swords. Dried flowers are used as a vegetable and leaves serve as a substitute for tobacco and tea."

In 1889 The Industries of Japan: Together with an Account of its Agriculture, Forestry, Arts and Commerce J. J. Rein describes comb making using tsubaki wood: "Ginger, or Ukon, is often used to give camellia wood the yellow colour of box, but cannot impart to it the more important qualities, equal fineness of grain, hardness and toughness."

For much more about ukon go to our web log page at http://printsofjapan.wordpress.com/2009/06/11/ukon-鬱金-turmeric/.

Lower down this page is an entry for tsuchigumo or "The Earth Spider" which is thought to be a metaphor for a band of thugs who terrorized parts of ancient Japan. In the earliest sources they are said to have been killed by a band of warriors who carried clubs made of tsubaki wood. This can be found in the Nihon-shoki.

"Tsubaki (camellia) surely holds the first place among the flowers for tea during the time of ro." [Ro (炉) is the word for the sunken hearth used between November and April in much of Japan.] (Quoted from Chado: The Way of Tea, p. 111) Tsubaki leaves were used to polish wood. (p. 112)

"Camellia japonica was the first species to be brought into cultivation m the West, and although it was described on the basis of material from Japan, probably all the early introductions during the late Eighteenth Century and early Nineteenth Century were from China. Linnaeus named the species in 1753 on the basis of the illustration and description in Engelbert Kaempfer’s Amoenitatum Exoticarum Politico-Physico-Medicarum, published in 1712." The first illustration of this plant to appear in the West was drawn by James Petiver, an English apothecary. It was published in 1701. (Quoted from: "The Chinese Species of Camellia in Cultivation" by Bruce Bartholomew)

In China the character used by the Japanese for the camellia, 椿, did not stand for the same plant. In China it represented the Cedrela sinensis. [Below is a detail of that plant supplied by the site run by Shu Suehiro.]

In Japan it combined the element for tree, 木, plus the element for spring, 春. Combined together they came to mean camellia. "It should be noted that traditional Japanese scholars not only knew that the name 海石榴 for camellia had been borrowed from T'ang China, but also recognized the fact that in China from Sung times on this name for camellia had become obsolete (having been replaced by shan ch'a) and was commonly misunderstood by Chinese readers of T'ang literature." This was the term used in the Man'yoshu (万葉集). ¶ In 777 the Japanese emperor gave the Chinese envoy a container of camellia oil. (Source and quotes from: Flowers in T'ang Poetry: Pomegranate, Sea Pomegranate, and Mountain Pomegranate by Donald Harper. Published in the Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 106, No. 1, Jan-March, 1986, p. 144.)

There is a brief remark in the Color Trade Journal, vol. III, for July to December 1918, that says "Camellia Japonica (Tsuboki); the leaves when pressed give a green coloring matter used for the dyeing of cheap mosquito nets." The '(Tsuboki)' mentioned above appears to be a mistake. |

||

|

|

||

|

Tsubone mise |

局見世 つぼねみせ |

A low class brothel. |

|

I have eaten in four star restaurants and I have eaten in dives. I have even eaten at MacDonald's a time or two or three or more. I mention this because most people will understand the distinctions between these establishments. They are enormous. The differences between a dish with truffles and armagnac and MacDonald's secret sauce are like the differences between a sip of Chateau Yquem and a swig of Ripple.

This is a truism even for the Japanese pleasure seekers in the 18th and 19th centuries. There were high class brothels and there were low class ones like the tsubone mise. The qualities between the women who served in these houses could not have been greater. If one wanted a four star treatment one had to pay for it. But one could even go a little lower than the woman of the tsubone mise.

"One important factor in the Yoshiwara's transformation of the first half of the eighteenth century was the competition imposed by neighboring Edo. The city of Edo was host to hordes of prostitutes ranging from relatively expensive 'gold cats,' 'silver cats,' and 'singing nuns,' to the low-class 'boat tarts'....and finally the 'night hawks' who operated in the open air." (Quoted from: Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan, by Cecilia Segawa Seigle, University of Hawaii Press, 1993, p. 128)

One last note: Year ago I saw the low caste prostitutes Seigle calls 'boat tarts' referred to as 'boat dumplings'. Either term conveys the idea nicely except that the latter sounds more W.C. Fieldish. |

||

|

|

||

|

Tsuchigumo |

土蜘 つちぐも |

"The Earth Spider" - a subject of Noh and Kabuki theater 1 |

|

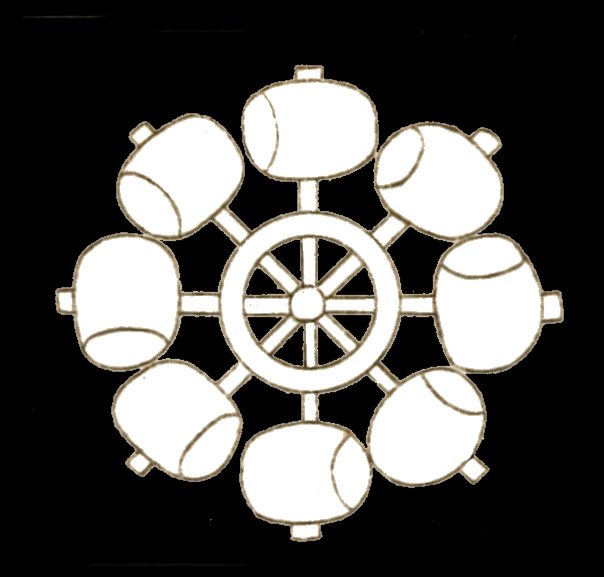

Tsuchi mon |

槌紋

つちもん |

Mallet crest or mon: The mallet as a family crest holds two nearly contradictory roles. In the example to the left you see Daikoku's mallet, the uchide no kozuchi, in a white circle representing wealth and prosperity. On the other hand, it could also be used as a military crest because symbolically it represents the owner potential for pummeling his enemies.

Another point of interest is the inclusion of the 'celestial' or 'sacred jewel' clearly seen in left hand flattened side of the mallet shown to the left. More can be found about this motif in our entries for both hōju and yakara no tama. |

|

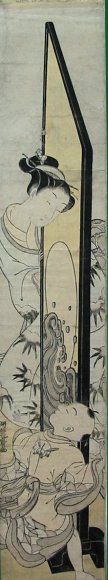

Tsuitate |

衝立 ついたて |

A free-standing single-panel screen.

The image to the left is print by Koryusai from the 1770s. It shows a mother (?) and child playing by running around a tsuitate.

To see a clearer and larger image of this print click on the number to the right. 1 |

|

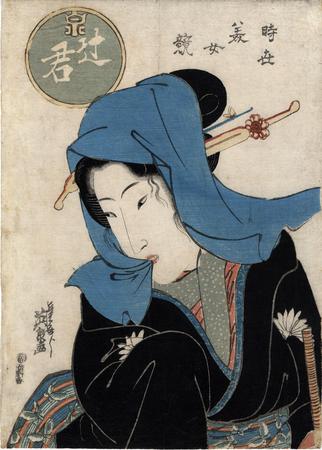

Tsuji-gimi |

辻君 つじぎみ |

The lowest class of prostitute.

The image to the left is an Eisen from the Lyon Collection. It has the term tsujigimi in the title. To see more information about this print click on the one shown here. |

|

Timothy Clark in the great Utamaro catalogue says that tsuji-gimi literally means "crossroads girl." This confounds me. Clark's understanding of Japanese is light years beyond anything I would ever hope to reach, but my reading of these two characters would be - using Nelson - "crossroads mister." ('Crossroads' could also be read as 'street corners.') Perhaps this is completely explicable in the same sense as a beckoner who says 'Hey sailor.' The 'mister' here is a reference to the 'john' and not the whore herself.

Tsuji-gimi can also be referred to as yotaka (夜鷹) which translates as nighthawk or street walker.

Years ago, many years ago, I read that the lowest rank of unlicensed prostitutes were often called 'boat dumplings.' Often women who had outlived their prime as courtesans - and that could be a very few short years - were lost as to what to do. Many of them tried to eke out a living by the only thing they really knew how to do well. Since traditionally many red-light districts were located near waterways hence the appellation 'boat dumplings.' |

||

|

|

||

|

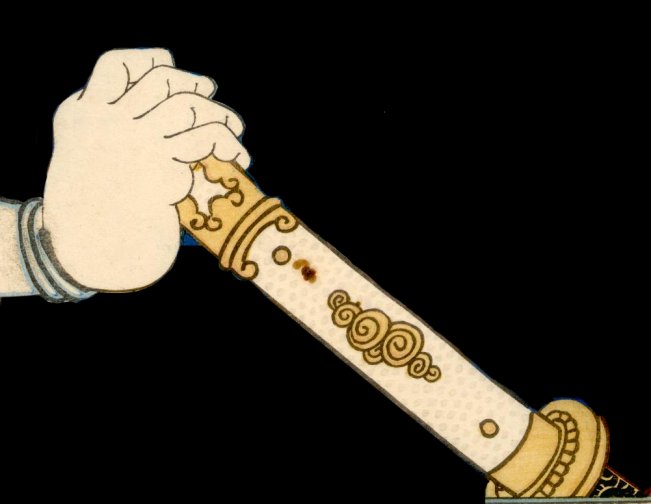

Tsuka |

柄

つか |

The hilt (haft) or handgrip of a sword, dagger or knife.

Below is the front and back of a tsuka we found at commons.wikimedia. It is from the collection of the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore. It was designed by Ishiguro Masaaki (1813-37) and illustrates scenes from the story of Kamatari and Tamatori. Their curatorial files describe it thus:

|

|

|

||

|

Tsuka |

塚 つか |

A mound, heap, tumulus, tomb, barrow: tsuka sometimes is pronounced -duka or -zuka.

Above is a detail from a Toyokuni III/Hiroshige print from 1855. |

|

|

||

|

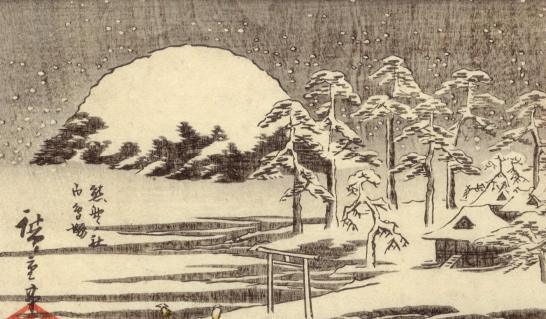

Tsukimi |

月見 つきみ |

Moon viewing: Traditionally this was celebrated on jūgoya (十五夜) or the 15th day of the eighth month. |

|

"The Japanese adopted the Chinese custom of setting out melons, green soybeans, and fruits in the garden as offering to the moon on this day. Jūgoya is considered to be the 'harvest moon' and is an occasion for thanksgiving and partying. Sprays of susuki (eulalia) are displayed on the veranda and tiny skewered dumplings (dango) and vegetables are offered to the moon. It is said that displaying susuki, which resembles the rice plant, will ensure a good harvest."

"Moon viewing is a common theme in Japanese poetry... It ranks with snow viewing and hanami (cherry-blossom viewing) as the three most favored settings for declarations of love and poetic outpourings of the soul." Quotes from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 5, p. 248, entry by Inokuchi Shōji. |

||

|

|

||

|

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi |

月岡芳年 つきおか.よしとし |

|

|

Tsukubai |

蹲い

つくばい |

A stone basin set in a tea house garden used for ritual washing and rinsing. "Rikyū stated that the principle of tea is only to boil water, make tea, and drink it. The Roji, or the garden path leading to the tearoom, was a place for guests to rid themselves of their desires and wills in anticipation of the pure experiences of tea. As such, the tsukubai, a stone water basin set on the path for the guests to wash their hands, has an important role. Rikyū designed water basins in such a way that the guests had to bend over to wash their hands. In a similar manner the entrance to the tearoom, the nijiriguchi (from the Japanese nijiru meaning crawl), also required humbling postures intended to induce humility and openness." Quoted from: Architecture, Culture, and Spirituality, p. 207.

"The most famous washbasin is said to have been made of the cornerstone of Imperial Castle in Korea, brought to Japan by the samurai Kiyomasa Kato during the Korean wars, and presented to Hosokawa. This washbasin is located several steps below the garden level, so that people using it to cleanse their hands and minds before entering the tea house are afforded an enhanced feeling of solitude." Quoted from: Japanese Gardens: Tranquility, Simplicity, Harmony by Mehta and Tada.

The image to the left was posted at Wikimedia.commons by Totorin. It shows the Tsukubai at Tofuku Temple in Kyoto. |

|

Tsukumo-gami |

付喪神

つくもがみ |

Inanimate domestic utensils possessed with spirits. "Around the fourteenth century... [the] Japanese began to believe that spiritual entities reside not only in nature but also in the objects that people make..." A spoon could place a curse on someone, a pot could change itself into an oni and if venerated and shown proper respect all such items could become kami in time. "By the middle of the sixteenth century, however, phantom household objects were beginning to swagger through the streets at night." Of course, this existed only in the minds of the most superstitious - which included just about everyone - and artists who portrayed them.

"Around the sixteenth century, the general name for specters of utensils was tsukumo-gami. Tsukumo means ninety-nine, and tsukumo-gami can be taken to mean literally 'the spirit... of a utensil that is ninety-nine years old.' "

"From the Kamakura period (1185-1333) onward, one prevalent image of mono-no-ke was the tsukumogami, common household objects with arms and legs and an animated — even riotous — life of their own. According to 'Tsukumogami-ki,' a Muromachi-period (c. 1336-1573) otogi- zōshi ('companion book') tale, 'When an object reaches one hundred years, it transforms, obtaining a spirit [seirei], and deceiving [taburakasu] people's hearts; this is called tsukumogami.' The word is thought to be a play on tsukumo-gami, with tsukumo indicating the number ninety-nine and gami (kami) denoting hair; the phrase can refer to the white hair of an old woman and, by extension, old age. The premise is that, when any normal entity — a person, animal, or object — exists for long enough, a spirit takes up residence within the form." Quoted from: Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese Monsters and the Culture of Yokai, by Michael Dylan Foster, p. 7. |

|

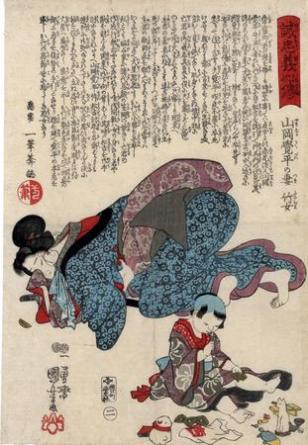

Tsuma |

妻

つま |

Wife - a term often used in identifying characters in ukiyo-e prints.

To the left is a Kuniyoshi print from the Lyon Collection. It shows the wife of Yamaoka Kakubei, one of the 47 Loyal Retainers. She is weeping as her child plays nearby. The print has the word 'tsuma' in the title. |

|

Tsumugi |

紬

つむぎ |

Pongee - a soft, thin cloth woven from rough silk.

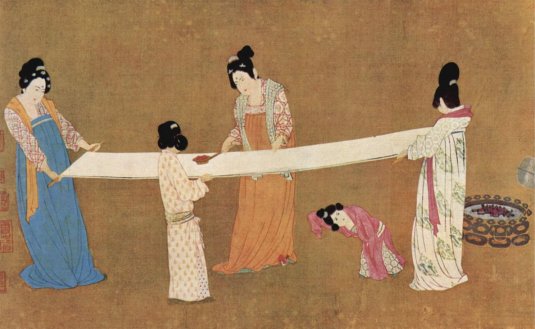

The image shown above is an early Song Dynasty copy of an even earlier painting. It is from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, but we found it at commons.wikimedia. It shows a group of ladies examining a newly created silk cloth which looks very much like pongee and may even be in that form.

The detail of the Harunobu to the left shows "A young man attired as a date kommusō... The young man carries a shakuhachi and a deep basket hat (tengai), and wears a friar's robes of pongee silk (tsumugai), together with a black kesa (Zen stole)." The quote is from the catalogue of David Waterhouse of the Harunobu collection at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, vol. 1, p. 313.

Click on the image to the left to go to the page devoted to the full print and to see what else Waterhouse said about it.

"The parts of the cocoon that are unsuited to reeling (beginning and end) are often hand spun to form noil (tsumugi), or second-class cocoon pulled and stretched to form batting (mawata) for lining clothes or stuffing comforters. A rural textile style adopted by some modern artists is pongee (tsumugi), which has reeled, partially de-gummed warps and hand-spun wefts." Quoted from: Encyclopedia of Contemporary Japanese Culture, text by Monica Bethe, p. 460. |

|

Tsuno |

角

つの |

Antlers or horn motif: Dower believed that antlers were chosen for designs originally because of their symmetry. However, during the period of feudal warfare they were adopted by various families as their crest or mon because of their martial nature.

Source: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 88. |

|

Tsunokakushi |

角隠し つのかくし |

A bridal headdress. Literally a 'horn cover' it is meant to cover the horns of jealousy. Jealous women were said to grow horns and become devils. Hence the headdress is said to remind women to fight off feelings. Timothy Clark notes that the tsunokakushi was worn "...to protect [a woman's] hair from the dust of travel..." during a bridal journey. |

|

Tsurezugegusa |

徒然草

つれづれぐさ |

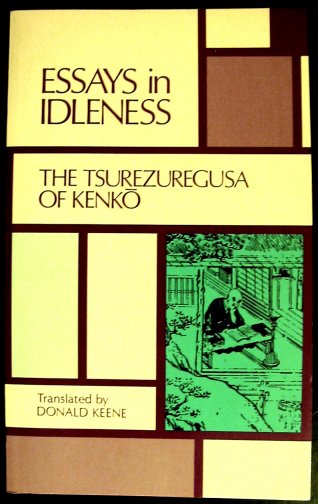

"Essays in Idleness (Tsurezuregusa) is a collection of essays... It has exercised an influence out of all proportion to its bulk, and would surely be included in any list of the ten most important works of Japanese literature." The birth and death dates of its author's life are unknown, but believed to be 1283 to 1350. Known to us as by his Buddhist priestly name as Kenkō he can also found under his lay names Urabe no Kaneyoshi and Yoshida no Kaneyoshi. "His family were hereditary Shintō priests of modest rank..." (p. xiii) ¶ "Kenkō was able, thanks to his abilities as a poet, to secure a place at the court. Kenkō's poetry is likely to strike us as conservative or even dull, but these qualities were precisely those most esteemed by the reigning school of poetry, which frowned on innovation and originality as betrayal of tradition." (p. xiv) |

|

Tsurieda |

吊り枝

つりえだ |

Hanging branches: "...decorative borders of artificial flowers or branches suspended over the stage (from the hiōi) in dance plays..." Sometimes cherry blossoms are displayed. At other times it is maple leaves or pine branches.

Source and quote: New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of kabuki jiten, compiled by Samuel L. Leiter, 1997, p. 669.

There are numerous prints which have sold or are presently offering which prominently display tsurieda. The image detail to the left is from a diptych by Kunitsuna. To see the full print click on the number one to the right. For other examples click on the other numbers. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 |

|

Tsuru |

鶴

つる

|

The crane has a rich history among the Japanese and Chinese. Often associated with the pine, bamboo and tortoise the crane has come to symbolize longevity. It also was a vehicle for certain Taoist immortals.

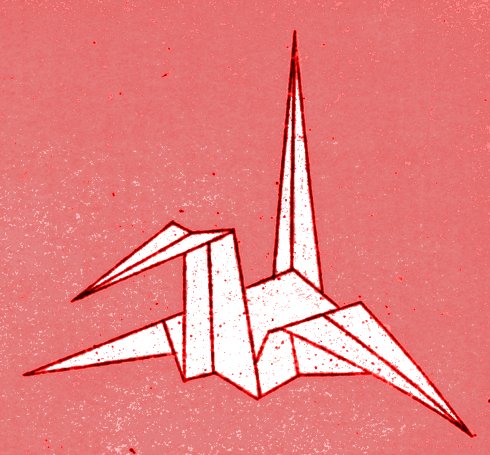

On the left are two of many variations of the crane motif used for both family crests or, as in the case of the origami example on the bottom, merely decorative design. If you look carefully you will occasionally find origami birds decorating the kimonos of women and children in ukiyo prints. Source: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 88.

A Red-crowned crane (Grus japonensis) at the Columbus Zoo. Posted at Wikimedia commons. |

|

Tsuru |

弦

つる |

Tsuru is an archer's bowstring.

In "The Tale of Genji" in chapter 4 the prince has taken his most recent infatuation away from her lodgings to a dilapidated and eerie structure. Spooked by their new surroundings Genji orders his guards to strum their bowstrings. "Have my man twang his bowstring and keep crying warnings." In footnote 43 Royall Tyler explains that this practice was "To repel the baleful spirit."

As one of his attendants was leaving him "The young man disappeared toward the steward's quarters, expertly twanging his bowstring (he belonged to the Palace Guards) and crying over and over again, 'Beware of Fire!'"

Footnote 44: "An all-purpose warning cry."

Source and quotes: The Tale of Genji, translated by Royall Tyler, vol. 1, p. 67.

In section 56 of Sei Shōnagon's 'Pillow Book' entitled 'The Roll-Call of the Senior Courtiers' the author wrote: "As soon as the roll-call is finished one hears the loud footsteps of the Imperial Guards of the Emperor's Private Office, who come out while twanging their bowstrings." I find it interesting that both contemporaries, Sei Shōnagon and Murasaki Shikibu, bother to mention the twanging of the bowstrings. Obviously it was a well known and important ritual act in the late 10th century.

Quoted from: The Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon, translated by Ivan Morris, Penguin Books, 1979, p. 76.

James Hepburn listed meigen [鳴弦] in his Japanese-English dictionary as "Twanging a bow-string to keep off evil spirits." This is still practiced during Setsubun (節分) which marks the end of Winter. Beans are tossed because they are considered particularly effective in driving away demons. |

|

Some musings: The tsuru is the same word used for archery as for that of musical instruments. So, the connection between the twanging of the warriors bowstring to ward off evil and the mystical power of music to perform wonders is only reasonable.

Orpheus (オルペウス), the son of the muse Calliope (カリオペ - ), according to Ovid (オヴィッド), used his talents to control the world about him. When set upon by the Ciconian women one of them threw a great stone at him. "...as it hurtled [through the air the stone] was overcome in midair by the harmony of voice and lyre and fell prone at his feet like a suppliant apologizing for so furious an assault."

Pythagoras (ピタゴラス) of Samos (c. 580-496 B.C.) saw a direct connection between music and math. His conclusions often mystical were also grounded in logic and fact. Pythagoras is quoted as having said that "There is geometry in the humming of the strings... there is music in the spacing of the spheres."

There's music in the sighing of a reed; There's music in the rushing of a rill; There's music in all things, if men had ears; Their earth is but an echo of the spheres. (Lord Byron - バイロン卿)

There are numerous other examples of the controlling powers of music in both the East and the West: Odysseus (オデユッセウス) and the Sirens (サイレン), invocating chants like the Om mani padme..., the Pied Piper of Hamlin (ハメルンの笛吹き?), etc. But there is one from my childhood which strikes a particular chord, the Buster Brown Show. The host would say: "Pluck your magic twanger Froggy" and a puff of smoke would appear along with Froggy himself. What happened after that is a haze for me, but I think they sang and danced while I sat there slack-jawed and wide-eyed. There obviously wasn't much separating my beliefs from that of Genji's at the time.

One more thought: The strings of the harp are often related to conceptualizations of heaven in the Christian West. In European paintings (King) David is often shown playing a harp, a Greek instrument and probably an anachronism, casting his glances skyward. The symbolism is absolutely clear.

In The Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon on p. 342 footnote 392 Ivan Morris noted that "During the course of each of the night watches an officer would strum his bowstring to keep away evil spirits; then, after naming himself, he would announce the time in a stentorian voice." This spurred me to do further research and the to look into the use of noise making as a form of magic. In Shinto: (the Way of the Gods) by William George Aston published by Longmans, Green and Co. in 1905 on page 335 the author notes made by "shaking or jingling talismans..." In the next paragraph he adds: "Part of the outfit of a district wise-woman or sorceress in recent times was a small bow, called adzusa-yumi, by twanging which she could call from the vasty deep the spirits of the dead, or even summon deities to her behests. Another small bow, called ha-ma-yumi (break-demon-bow) [破魔弓 or はまゆみ] is given to boys at the New Year." In ancient times, during the tsuina (追儺) ceremony or 'bean tossing' meant to drive out demons at the New Year, a fellow would dress up at court as demon and young men would shoot arrows at him using peach wood bows. Perhaps the twanging of the bow came to act as a warning. It certainly saved searching for or wasting a lot of arrows. Peach wood staves were used for oni-yarahi (鬼やらひ) or 'demon-expelling'. Aston also notes on page 189 that the peach wood came to stand for the male element and hence was thought of as phallic.

In the Nō play Aoi no Ue (葵上) or "Lady Aoi" a sybil is brought in at the beginning to conjure up an evil spirit which is afflicting Princess Aoi. The sibyl beats on a drum "...and twangs her of catalpa wood..." The spirit comes forth, announces who she is and strikes a single folded robe, stage center, which is symbolic of the Princess. The vengeful spirit is that of Lady Rokujō who was "...superceded and disgraced..." by the Princess. Both are characters from The Tale of Genji. The sibyl - see our entry on miko - can call the spirit, but cannot dispel it. A holy man is brought in and he invokes the name of Fudō to dispel and then save the spirit of Lady Rokujō through her eventual salvation into a state of Buddhahood. (Source: The Catalpa Bow: A Study of Shamanistic Practices in Japan by Carmen Blacker)

Below is an image of a catalpa tree from a park in Belgium posted at commons.wikimedia by Jean-Pol Grandimot.

"The bow and arrows which the medium for the sun goddess wore about her person are likewise to be found in the panoply of the continental shaman. There the bow is not so much a weapon as an instrument of magical sound, a one-string zither which when twanged emits a resonance which reaches into the world of spirits, enabling the shaman who manipulates it to communicate with that world. For the miko, from ancient times until the present day, the bow has likewise been an instrument whose sound magically compels spirits to draw near.... We shall also see in a later chapter that a similar bow is still used by blind mediums in the north when they summon ghosts and kami. [¶] For the ancient miko, however, that the bow had a further function. It was a torimono, an object which 'held in her hand' as she danced, and which acted as a conductor along which the deity could make his entry into her body. To this day the bow, together with the sword, spear, bamboo wand and branch, numbers among the nine varieties of torimono which the kagura dancer may hold in her hand during a performance." (Ibid., pp. 106-7) |

||

|

|

||

|

Tsuru-bishi |

鶴菱

つるびし |

Nakamura family crest of a crane (in a lozenge, sometimes.) 1

"One of Shikan I's crests was tsuru-bishi (a crane in a diamond-shaped background) and this, too, was used by his fans. The Nishimuraya family all had this crests on their purses, tobacco cases, furoshiki [a cloth used to carry small items...]. Nishimuraya's favorite hobby was indoor archery, and all the equipment for this was decorated with this crest; the feathers of the arrows were shikancha [a dull bitter red brown] in color. Hachiku from Nagahori put this crest not only on his small furniture but also his letter-paper. Merchants that came to Kiyu's shop to do business had to prepare a paper crest with the crane design and paste it over any wild orange crests that they had on them."

The image to the left is a detail from an 18th century robe in the Kyoto National Museum. |

|

Tsurugi |

剣

つるぎ |

Sword motif used in many different combinations with other symbols/images such as the sun, plants and butterflies to give a more martial sense to each image. |

|

Tsurukusa |

蔓草 つるくさ |

A vine or creeper: Often used as a decorative motif on paintings, kimonos, etc.

This is a term which has been very difficult to track down with a precise botanical example. It is mentioned by Günter Zobel in his contribution to The Origins of Theater in Ancient Greece and Beyond: From Ritual to Drama (Cambridge University Press, 2007, p. 296). In a re-enactment of the raucous dance performed by Ame-no-Uzume used to lure Amaterasu out of her self-imposed confinement Ame-no-Uzume "...put a vine, called tsurukusa, inside the cord tucking up her sleeves and attached it to her frontlet." ¶ That would certainly make this a very powerful and ancient symbol. However, in the two copies of the Kojiki and one of the Nihongi which I have at hand the descriptions vary slightly and the exact term tsurukusa is not used. In Basil Hall Chamberlain's Kojiki translation "...Her Augustness Heavenly-Alarming-Female [i.e., Ame-no-Uzume] hanging [round her] the heavenly clubmoss of the Heavenly Mount Kagu as a sash..." (Published by Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1993, p. 64)

*The second set of brackets is Chamberlain's, the first one mine.

In Donald L. Philippi's translation "...Amë-nö-uzume-nö-mikötö bound up her sleeves with a cord of heavenly pi-kagë vine..." (University of Tokyo Press, 1995, p. 84)

In W. G. Aston's translation of the Nihongi "Moreover Ama no Uzume no Mikoto... took club-moss and of it made braces..."(Published by Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1993, p. 44)

I don't know if you have noticed or not, but not only the spellings vary greatly, but, also, club moss is not a creeping or climbing vine. This compounds the confusion. |

|

Tsuruya Kokei |

弦屋光渓 つるや.こうけい |

Artist - Born 1946 1 |

|

Tsuruya Namboku V |

鶴屋南北 つるや.なんぼく |

Major dramatist 1796-1852 1 |

|

Tsūshō |

通称 つうしょう |

Nickname, alias |

|

Tsuyazumi |

艶墨 つやずみ |

Glossy black: More than one layer of a high quality black ink mixed with animal glue or nikawa (膠) is laid down. Once printed the surface is burnished with a piece of ivory or something similar until that area is shiny. This technique is most often used on hair, fabrics, lacquer, armor, etc. |

|

Tsuyukusa |

露草 つゆくさ |

Day flower or "rainy season plant" from which aigami is made 1 |

|

Tsuzumi |

鼓

つづみ |

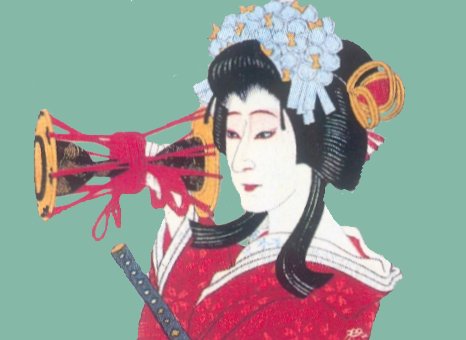

"A traditional hourglass-shaped drum; it consists of two leather skins each sewn onto an iron ring larger in diameter than the drum body, then laced with ropes onto the lacquered wooden drum." Several such instruments were introduced into Japan prior to the Nara period (710-794). Frequently used in Noh and Kabuki theater. "...played with the right hand and fingers..." Quoted from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 8, p. 119-20, entry by Kojima Tomiko.

The detail to the left is from a print by Natori Shunsen.

To the left we had added graphics for three different crests using the tsuzumi motif. John W. Dower noted that drums were "Not introduced as a design motif until late in the feudal period..." Quote from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p 110.

The one below is from a Kunisada print showing a family crest on the headband being worn by an actor playing a role. It is an interesting variation on the drum motif because it looks like an hourglass or one of those early European stools which were meant for sitting. However, here it is shown with an organic element surrounding it.

"During the Toka-sechi-e of the Atsuta-jingű, the sound obtained by a priest on a small drum (tsuzumi) indicates whether the harvest will be good or bad." Quoted from: Shinto: At the Fountainhead of Japan by Jean Herbert, p. 153. |

|

LINKS TO OUR OTHER INDEX/GLOSSARY PAGES Click on any of the pages listed below!

|

||

|

Hotoke thru Igaya |

||

HOME

HOME