JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

Hoshi thru Hotaru |

|

|

|

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Hoshi, Hōshi, Hoshi-ami, Hōsō, Hōsō-e and Hotaru

星, 法師, 干し網, 疱瘡, 疱瘡絵 and 蛍 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Hoshi |

星

ほし

|

Hoshi, i.e., star motifs: If I could make a game of this I would show you the two images on the left and ask you to guess what they represent. Then I would show you the correct answer on another page. But that is a lot of work. Personally I doubt that many of you would guess that they are variations on star motifs. I know that I wouldn't get it right. But that is what they are.

Dower has quite a bit to say about these patterns noting that the Japanese of the Nara and Heian periods were quick to accept Chinese concepts of astrology and geomancy. "Each person had his own particular guardian star, determined by his date of birth. Similarly, certain stars and constellations had their own particular associations and were believed capable of existing protective influence."* Scrolls, clothing and the carriages of the aristocracy were often decorated with these circular patterns. (Remember there are many more variations on this motif than the two shown here.)

Because of the auspicious nature of star symbolism quite a few warrior clans adopted this motif as their crest.

"A depiction of three stars...was associated with Orion [オライオン] and called the 'three warriors' or 'stars of the general' in both Chinese and Japanese. In a similar manner, seven or more stars were associated with worship of Ursa Major...[ 大熊座]" (Source and quotes from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 43)

*Above I quoted Dower stating that each person had a guardian star based on his/her date of birth. That is not dissimilar to the worship of patron saints among the Catholics. Recently I was talking to my friend Scott Alexander Jones (スコット.アレクサンダー.ジョーンズ) and we were talking about names. When I mentioned that I liked his middle name he told me that it didn't come from Alexander the Great, but from someone named St. Alexander. Scott is only twelve right now and didn't know which St. Alexander it was, but he knew that it was one of them. Although four Alexanders have their feast days in October none of them line up exactly with his birthday. |

|

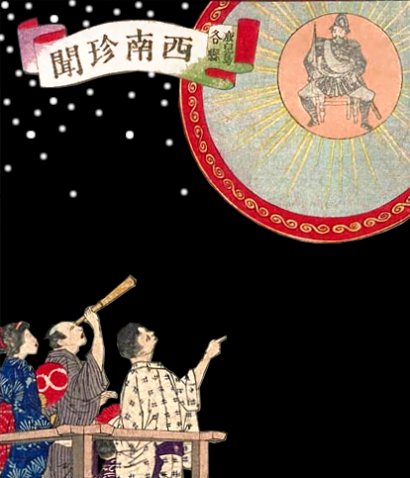

Literally hoshi means star(s). There is a curious reference to a red star which appeared toward the end of the Satsuma Rebellion (西南の役) of 1877. The superstitious said that it was the incarnation of the deceased leader of that revolt, Saigō Takamori (西郷高盛). Some people even claimed that they could see his image when they looked at it through a telescope. A number of newspapers tried to quell this outburst of astronomical zeal by stating that the red star was actually Mars. Below is our doctored version of a print by Kunimasa showing this theme.

A hoshi kabuto (星兜) is a descriptive term for a particular type of samurai - or daimyō - helmet. "There were essentially two types of hachi (helmet bowl): tsuji (ribbed), and hoshi (star, i.e. riveted) bachi." (Quoted from: The Samurai by Anthony J. Bryant, p. 45) "For a time, near the mid-to late 16th century, hoshi kabuto were replaced by tsuji kabuto, but the former staged a very successful comeback. Hoshi kabuto were originally intended for a small number of plates..." |

||

|

|

||

|

Hōshi |

法師 ほうし |

Buddhist priest or monk, bonze. W.G. Aston in his footnotes to his translation of the Nihongi says that hōshi is a priestly rank.

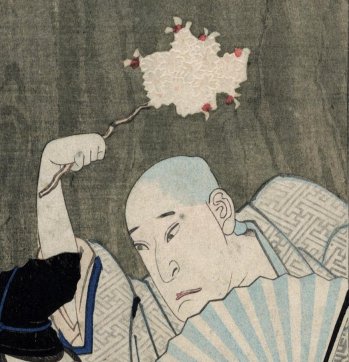

The image to the left is a detail from a print of The 6 Immortal Poets by Shigeharu from 1834. This one was a hōshi. The full print is in the Lyon Collection. Click on the image to see it and information about it. |

|

There is a sub-genre of Muromachi period (1392-1573) tales which include those of the love of an older Buddhist priest for a young male acolyte or chigo (稚児). "Another prominent category is priest tales, which include tales of awakening (hosshin) and confession, such as The Three Priests (Sannin hōshi), and stories about relationships between an older Buddhist priest and a young boy acolyte... in which love is often presented as a means to help the priest achieve enlightenment. The most famous of these is A Long Tale for an Autumn Night... in which a priest from Mount Hiei and a chigo from Mii-dera temple are caught in a human struggle between the two temples." (Quoted from: Traditional Japanese Literature: An Anthology, Beginnings to 1600, p. 1099)

One category of itinerant priests were the blind biwa hōshi (琵琶法師). During the Kamakura period (鎌倉時代: 1185-1333) they accompanied armies. "The first variants of The Tales of Heike were probably recorded by writers and priests associated with Buddhist temples who may have incorporated Buddhist readings and other folk material into an earlier chronological, historically oriented narrative. These texts in turn were recited from memory, accompanied by a lute (biwa) played by blind minstrels... who entertained a broad commoner audience and had an impact on subsequent variants... which combined both literary texts and orally transmitted material. The many variants... differ significantly in content and style, but the most famous today is the Kakuichi text... This variant was recorded in 1371, by a man named Kakuichi [覚一], a biwa hōshi who created a twelve-book narrative shaped around the decline of the Heike (Taira) clan.... [¶] Thanks largely to Kakuichi, the oral biwa performance of The Tales of Heike eventually won upper-class acceptance and became a major performing art, reaching its height in the mid-fifteenth century. After the Ōnin war (1467-1477), the biwa performance declined in popularity and was replaced by other performance arts, such as nō and kyōgen (comic drama), but The Tales of Heike continued to serve as a rich source for countless dramas and prose narratives." (Ibid., p. 707)

Donald Keene discusses the origins of Kyōgen on pages 1030-31 of his Seeds in the Heart: Japanese Literature from Earliest Times to the Late Sixteenth Century: "It is not clear from existing sources when and how Kyōgen acquired its name. The art itself may have originated not as a stage performance but as recitations rather in the manner of present-day rakugo. The earliest reference to what seem to be Kyōgen performers occurs in a document dated 1350, where mention is made of okashi hōshi ('funny priests'), who seem distinct from both sarugaku (Nō) and dengaku actors. These 'funny priests' entertained audiences with their adroitly delivered monologues, and before long they acquired ado, or 'partners,' who served as foils." Okashi is 可笑しい.

Prior to the development of Nō theater performers of its folk antecedents were known as sarugaku hōshi and dengaku hōshi..." and, of course, biwa hōshi. "Inevitably, the term hoshi dropped out of usage as a designation for formally ordained priests, being replaced by other terminology, but its continued use in the names for many types of simple folk performers reflects within a folk Buddhist context the underlying understanding of the semireligious function of the performing arts." (Source and quotes: The Legend of Semimaru Blind Musician of Japan by Susan Matisoff, p. 18)

See also our entry on mekura or blindness. |

||

|

|

||

|

Hoshi-ami |

干し網(?)

ほしあみ疱瘡 |

Fishnet motif : I do wish I could tell you something significant or deep about this motif, but so far I have come up with zilch. However, I am adding the detail below from a Kuniyoshi print. Lovely, isn't she?

|

|

Hōsō |

疱瘡 ほうそう |

Smallpox - We started out to expand our entry on aka-e or red pictures meant to ward off smallpox or help people suffering from it. However, the information about this subject requires its own listing. |

|

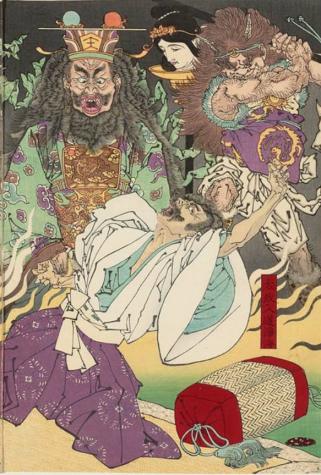

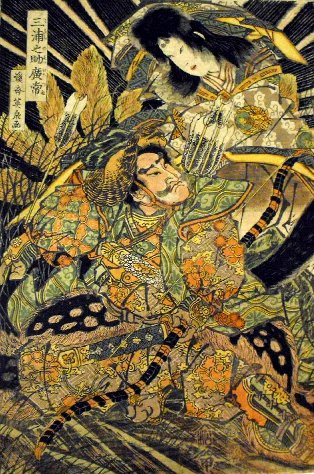

The image above shows details from a print by Kuniyoshi. On the left is Minamoto Tametomo (1139-1177 or 1170 depending on your source and who you believe: 源為朝), an historical figure of Homeric proportions who is even described in the Historical and Geographical Dictionary of Japan by E. Papinot (Charles E. Tuttle Co., 1992, p. 380) in that way: "It is said he was 7 feet high and of a Herculean strength. On the right are the god of smallpox accompanied by children's toys which act as protection against the disease or as amulets which would lessen its impact once it has arrived. Notice that each of them is either red or has something red accompanying them. ¶ There seem to be a multitude of stories told about Tametomo with several variations on each of these. Here is one account from Warriors of Old Japan: And Other Stories by Yei Theodora Ozaki and Hugh Fraser (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1909, p. 18-19): One day our hero, who was once again in exile, was walking along a shore watching the waves. In the distance, a great distance because he had incredible eyesight, [what else?], he spotted something small approaching him. It was a little old man. "Tametomo could hardly believe his sight; he had never seen anything so strange in his whole life [even though he had just returned from an island dominated by vicious red haired, red bodied, demons who he quelled and made his subjects]; he rubbed his eyes, thinking he must be dreaming, and looked and looked again. There sure enough was a tiny man, no bigger than one foot five inches high, sitting gracefully on a round straw mat." ¶ Tametomo walked to the edge of the water and asked the approaching figure "Who are you?" "I am the microbe of small-pox," answered the stranger pygmy. "And why, may I ask, do you come to this island?" inquired Tametomo. "I have never been here before, so I came partly for sight-seeing and partly with the desire to seize hold of the inhabitants - " answered the little creature. ¶ Before he could finish his sentence Tametomo said angrily: "You spirit of hateful pestilence! Silence, I say! I am no other than Chinsei Hachiro Tametomo! Get out of my presence at once and take yourself far away from this place, or I will make you repent the day you ever came here!" As Tametomo boomed the microbe pygmy man kept shrinking until he was only the size of a pea. It apologized and said it hadn't realized that this was one of Tametomo's possessions and said it would never come again and "...to this day the islanders [of Oshima] ascribe the immunity they enjoy from the horrible pestilence to Tametomo..."

It has been noted many times by numerous authors and scholars that the assistance of gods have been sought for their prophylactic, palliative or curative powers. There is Lourdes, for example. Or, in the Plague by Camus Father Paneloux tells the people of Oran that their lifestyles have brought on the wrath of God. (The priest eventually softens his opinions because of the extreme suffering and in the end even he is consumed.) Or the example of Jesus exorcising the demons and driving them into a herd of pigs. (Matthew 8.28-34) Even today many contemporary fundamentalist Christians believe that the curse of AIDS and the attacks of September 11th are due to the displeasure of God. So, shouldn't seem so far fetched that the Japanese would seek salvation through a person who has been raised to the level of a god? ¶ In 1917 "American Medicine" published its 23rd volume. On page 117 of its February edition Dr. T. Yaétsu noted that it was reportedly the bravery of Tametomo which drove the scourge of smallpox away from the island of Oshima. Some people believed that if they painted a picture of Tametomo's house "...on a piece of red paper and paste this on the door-posts of their own houses, they can prevent the visit of the spirits of disease." Dr. Yaétsu adds that by the early 20th century the afflicted household would also send for a medical doctor, too. Better safe than sorry. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

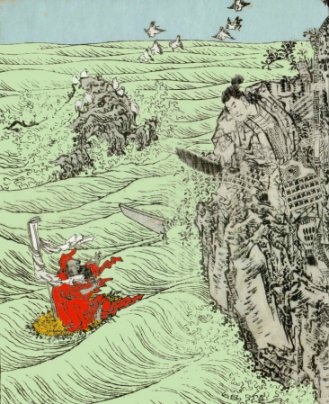

The day after we posted the Kuniyoshi image of Tametomo before the god of smallpox accompanied by toys associated with that disease our great contributor E. sent us the Kuniyasu image shown to the left above. Clearly it portrays the confrontation between the approaching smallpox-microbe-man who thought it might be nice to go sightseeing on the island of Oshima. It does not conform to our quoted account from the Warriors of Old Japan: And Other Stories where Tametomo, standing on a beach, warns the disease to stay away. Such differences are incidental. Besides, remember the Japanese already believed that Tametomo was 7' tall and the smallpox-man only 17". By placing our hero on the edge of a cliff he would have seemed that much larger to the disease. (Of course, that is my theory, but then again it might only have been Kuniyasu's artistic license or perhaps he was working from another account. Who knows? I don't.)

Now for the detail shown on the right above: It is particularly fascinating. It operates on so many levels at once. The figure of smallpox as clad in red makes perfect sense. Like the story told above he is riding the waves on a small, round, straw mat. However, even here Kuniyasu has added something new - a sail-like element made up of a Shinto religious prop. But the comparisons don't stop there: The smallpox-little-guy-microbe looks strangely reminiscent of Daruma, a buddhist deity. Daruma is generally bearded, frequently draped in red and is either shown with legs or without them. Here the microbe's left foot appears while its right leg is implied hidden below its robes. (Keep in mind that Daruma meditated before a wall so long that his legs rotted off.) Another oddity is that the face of the microbe seems to be reminiscent of that of a Chinese man or perhaps even a Taoist immortal. Either way, it might represent an unwanted (non-native) foreign curse. There is another Daruma/Bodhidarma connection which may simply be a matter of convenience: Smallpox is sailing toward Oshima on a tiny mat? Bodhidarma traveled from India to China by standing on a blade of grass - or some such thing. This connection with Daruma is made clearer by the inclusion of a red Daruma doll in the picture by Kuniysohi.

Above is a book illustration by Hokusai created as early as the first decade of the nineteenth century . It was published decades before the one by Kuniyasu (ca. 1845-6) which was sent to us by our contributor E. Clearly one was the model for the other. The Hokusai accompanies a text by Bakin. By the way, the coloring is ours.

In The Greatest Killer: Smallpox in History by Donald R. Hopkins (University of Chicago Press, 2002, p. 111) the author lists a number of epidemics which spread through Japan in the 11th and 12th centuries. He notes that a number of royal princes had contracted the disease some of whom died while others recovered. He even speculates, via a quote from Samson, that Kiyomori died of it in 1181. "...suffering from a high fever... suffering torments, crimson in face, and 'burning like fire.' ...he died that day." Below is a detail from a triptych by Yoshitoshi showing Kiyomori in his death throes. In the original he is backed by flames and figures from Hell. With the death of the 63 year old Kiyomori his rivals, the Minamoto, were able to seize power and consolidate their position.

According to Hopkins Tametomo's "...image, printed in red ink, was one of the most popular pictures Japanese families used to hang on the walls of their homes to protect or help cure family members from smallpox..." (Ibid., p. 112)

Japanese Dolls: The Fascinating World of Ningyo by Alan Scott Pate (Tuttle Publishing, 2008, p. 266) defines "hōsō-ningyō [as a] Talismanic doll form used to protect against smallpox. Usually decorated in a predominantly red palette. Typical figures used as hōsō-ningyō include a mythological water imp (shōjō), Shoki the Demon Queller, Minamoto no Tametomo, Daruma, and a long-eared owl."

Above is a detail from a print by Kuniyoshi showing a red Shoki.

I always wondered why there were so many red Shokis around. Not that they are common, but I had seen quite a few of them over the years and found them very striking. Now I know why they are red: Smallpox. Yup, that's it and we will explain more later. Soon hopefully. |

||

|

|

||

|

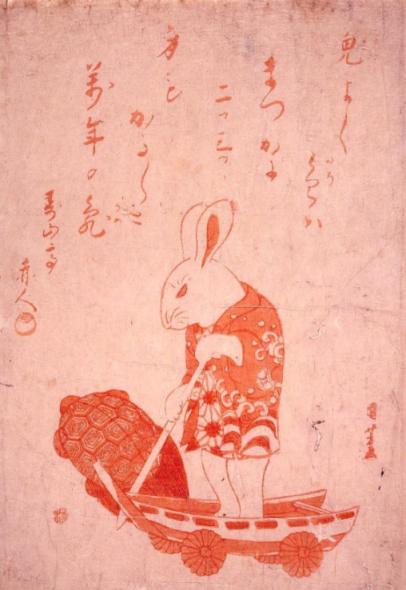

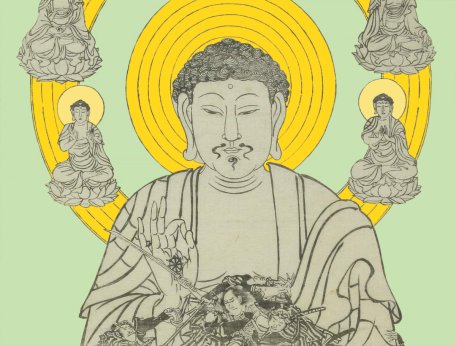

Hōsō-e |

疱瘡絵

ほたる |

Smallpox prints - Prints meant to appease or drive away the smallpox spirits. Rebecca Salter wrote at length about these prints in her Japanese Popular Prints: From Votive Slips to Playing Cards, p. 121: "Prevention was infinitely preferable to dealing with the illness, so efforts were made to confuse the smallpox kami and make him go elsewhere. In some parts of Japan, to protect newborns, the character for dog would be written on the child's forehead to fool the kami into not recognising it as a human child. If the worst happened and the disease was contracted then all the effort went into making sure it was as mild as possible. A lot of dos and don'ts included: no saké for 100 days; avoiding salty and spicy food; avoiding those with smelly armpits and avoiding the smell of latrines and burning hair and the comings and goings of religious people! A mixture of musk, cinnabar and castor oil plant was applied to the patient with a spell. It was painted between their eyebrows, on the bridge of the nose, hollow of the stomach, hands and feet, and the mixing bowl and brush were then thrown into the river. Alternatively, a printed calendar of the year of the child's birth was taken, their date of birth cut out and burned and the residue fed to the patient. This belief in the power of paper and sumi ink (and the written/printed word) was found in the practice of pilgrimage. If lucky enough to be given a votive slip by a pilgrim who had performed the circuit many times, it was said to be particularly beneficial to soak the slip in water and eat it."

See also our entry on aka-e for more information. |

|

Hotaru |

蛍

ほたる |

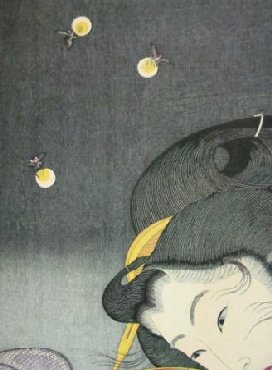

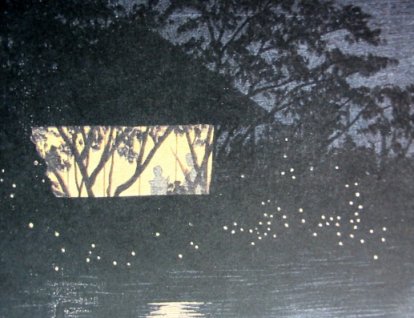

Firefly: Merrily Baird in her Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design (pp. 110-111) notes that "As early as the Nara period..." fireflies were a poetic symbol for passionate love. During the Heian period the nobility went on outings to view and capture these insects on warm summer nights. "From the Chinese, the Japanese appear to have derived the custom of viewing fireflies as souls of the dead..." The ones at the Uji River near Kyōto even came to represent the deceased warriors of the opposing armies of the struggle between the Minamoto and Taira clans during the 12th century. "Given it's size..." Baird concludes "...the firefly does not lend itself to solo treatment on a large scale."

The detail to the left is from a print by Yoshitoshi.

The modern Chinese word for fluorescence is made up of the characters for firefly (螢) and light (光). |

|

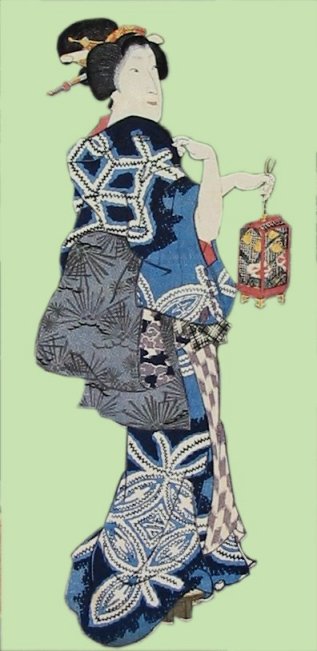

The image to the left is a detail of a print with certain figures by Toyokuni III, like the one shown above and the night background by Hiroshige. The bijin shown here appears to be carrying a cage filled with hotaru. She could have caught them herself as seen in an early print by Harunobu or she could have bought them from an hotaru-uri or firefly merchant. Such hawkers are mentioned in J. E. De Becker's Yoshiwara: The Nightless City (p. 14) as hanging out during summer months in the Yoshiwara.

The detail shown above is from a print by Kuniaki. |

||

|

These two details are both from prints by Kiyochika. The one below is from "Tennōji-shita Koromogawa" (天王寺下衣川 or てんのうじしたころもがわ) Koromo River below Tennōji Temple, 1880

|

The entry on fireflies in

the

Kodansha Encyclopedia

of Japan

entry by Saitō Shōji (vol. 2, p. 280) mentions the "...legend of a poor

scholar who unable to afford lamp oil, studied by the glow of fireflies in

the summer." Sei Shōnagon [清少納言] made a list of attractive

things and placed fireflies on a moonless night at the top of her list. "In

the Tale of Genji... Prince Hotaru, Genji's half-brother, catches his

first glimpse of Lady Tamakazura by the light of fireflies." Saitō ends this

section by noting the popularity of 'firefly viewing' during the Edo period.

"There were special boats for viewing fireflies at the river Ujigawa in

Kyōto and at Ishiyama on the shore of Lake Biwa.

The following entry on 'firefly viewing' is by Inokuchi Shōji. Hotarugari (蛍狩り) originally was a pastime for Heian aristocracy (794-1185), but by the Edo period (1600-1868) it was popular among all groups. "Since the number of fireflies in Japan has decreased because of pollution and agricultural chemicals, fireflies are raised for hotels and large restaurants, which sponsor firefly displays to attract guests." A wonderful web site run by the University of Virginia notes the use of pesticides as a major problem in the decline of fireflies. The pesticides kill kawanina (川蜷) or river snails off which firefly larvae feed. |

|

|

In Mock Joya's Things Japanese (Japanese Times, Inc., 1985 edition, pp. 124-125) children are described hunting for fireflies with fans and bamboo branches. When caught they were often put in cages covered in gauze. "In cities, hotaru are sold in cages at street stalls." "Hotaru-gassen [蛍合戦] or firefly battles are one of the most wonderful summer sights. Huge masses of fireflies come from different directions and mingle in confusion as they come together, making hillsides and streams bright with tiny yellowish lights."

There is a legend of an extremely pious, but poor old farmer named Kanshiro who makes a religious pilgrimage every year. However, he rarely travels during the summer months because he generally suffers from dysentery at that time. Nevertheless, despite all of his infirmities Kanshiro makes the journey every year. As long as he can get around he will pay homage to the gods. Finally he feels that this will be his last circuit and that he must go even though it is summertime. His neighbors raise a considerable fund to help him on his way. After a few days his old ailments strike again and he has to find a place to rest for a few days. Because he is unclean he feels that he cannot enter any shrines and that even the money he has been given is now tainted. Desperate to rest up he stops at a cheap inn and asks the owner, Jimpachi, to help him back to good health and to keep the money safe for him until that time. After several days he sets out again, but finds the inn owner has replaced his purse of coins with stones. Kanshiro returns to the inn and confronts the owner who denies the theft and with the help of others beats the old man to a pulp. Despite this the old man makes his way to Ise even though he has had to crawl and beg the whole way. By the time he returns home he is completely wasted. Some of the people who gave him the money believe his story. Others do not. He sells all his property to replace the funds which were stolen. When that is done the old man sets out again to scold the owner of the inn who now is living in considerable wealth. Once more the inn owner denies the charge of theft and drives the old man away. Driven by the authorities from the town because he is now a beggar the pious, old farmer dies, but not before he curses the now wealthy thief. Soon thereafter the inn owner falls ill and takes to his sick bed. A few days later a swarm of fireflies rise from the Kanshiro's grave and surround Jimpachi's mosquito-curtain. They are unrelenting trying to force their way in. Even their light dazzles the sick man. Jimpachi's neighbors try to kill the fireflies until they realize that each one they eliminate is replaced by a new one streaming directly from the old man's grave. The effort is futile and probably unwise. As soon as Jimpachi dies the fireflies disappear. (Source: Ancient Tales and Folklore of Japan, by Richard Gordon Smith, Bracken Books, 1986 edition, first published in 1918, pp. 282-86)

In the Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu both Seidensticker and Tyler translate the title of chapter 25 as 'Fireflies'. Waley, on the other hand, calls it 'Glow-Worm'.

A contemporary of the author of the Tale of Genji was Izumi Shikibu who wrote some very beautiful poetry. Steven D. Carter in his Traditional Japanese Poetry: An Anthology translates many of them like the one below from page 123. It combines the sense of self and soul and yearning in one brief passage.

So forlorn am I that when I see a firefly out on the marshes, it looks like my soul rising from my body in longing.

Another reading of the poem shown above is from Brower and Miners Japanese Court Poetry (p. 222):

As I fall in sadness At his neglect, the firefly of the marsh Seems to be my soul Departing from my very flesh And wandering in anguish off to him.

In The Clear Mirror: A Chronicle of the Japanese Court During the Kamakura Period (1185-1333) by George Perkins there is a particular beautiful poem by Minamoto Arifusa (源有房?: 1251-1319):

Thanks to the light shed by fireflies assembled at my window, I bathe in radiance beyond all expectation.

In 1511 the priest Sōchō, living in isolation wrote - as quoted from Song in an Age of Discord: The Journal of Socho and Poetic Life in Late Medieval Japan by H. Mack Horton, p. 155:

By the pinewood door lit by fireflies when it grows dark. One learns the meaning of tedium when one dwells in isolation.

Stephen Addis in his essay The Three Women of Gion in Flowering in the Shadows: Women in the History of Chinese and Japanese Painting discusses and compares the poems of Kaji, the grandmother, Yuri, the adopted daughter and Gyokuran, the natural born granddaughter. They lived and wrote in the late 17th to the mid-18th centuries. Each woman wrote about fireflies, but the first two appear to be allusions to longing and lost loves and the third simply dealt more directly with nature. As Addis points out the differences may have more to do with the events in each woman's life. Not only are these poems lovely and evocative, but considering the familial relationships, that much more interesting.

Kachi's poem

Flaming as they pass, the fireflies of the swamp - I would show them to an uncaring lover as my overflowing feelings.

Yuri's poem

Never extinguished can be the suffering that I will always feel - I am like the firefly that has scorched its own body.

Gyokuran's poem

Summer evening - over the shallow swampland, shining upon the waters are the entangled reflections of fireflies.

Haruo Shirane in his Early Modern Japanese Literature: An Anthology, 1600-1900 wrote about the use of fireflies in haiku as allusions/metaphors: "...those that mingle among the pinks are said to share the feelings of Prince Hyōbukyō..." Its footnote tells us that the reference is to the brother of Genji, in The Tale of Genji, in the Fireflies chapter. Hyōbukyō sees Tamakazura for the first time and only behind a screen in the light of the fireflies released by his brother, "...causing [Hyōbukyō] to immediately fall in love with her. The wild pinks (tokonatsu) refer to Tamakazura." (p. 173) Below is a photo of a tokonatsu (常夏) shown courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/plants-ta/tokona.htm.

Fireflies and lilies are said to stand for Minamoto Itaru, of the Tales of Ise, who peered into a woman's carriage with the aid of firefly light. Fireflies that "...on Mt. Hiyoshi are compared to the red buttocks of monkeys, and the ones that glitter at Mount Inari are thought to be foxfires."

Sorry. No monkey butts here, but at least this is a Japanes monkey as posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Alphonsopazphoto.

"Fireflies are also said to be the soul of China's Baosi..." who was transformed into the 9 Tailed Fox, Tamamo no mae. This creature bewitched the retired emperor Toba "...by disguising itself as a beautiful woman. Toba ordered Miura no suke Yoshiaki to kill her. At death she was tranformed into the Sesshōseki (殺生石) or Killing-Rock. Below is a detail from a print by Eisen showing Tamamo no mae being stalked. It is shown courtesy of our great friend Dan.

And then there is the haikai comparing monks to fireflies where there is a play on the word hajiri "...which means both 'holy men' and 'fire buttock' (lower part of a hearth) implying homosexuality, which was not uncommon among priest in the medieval period.

At Mount Kōya Even the fireflies in the valley are holy men

Sometimes Japanese poetry related to the firefly was both witty and inelegant. A poem quoted in Haikai Poet Yosa Buson and the Bashō Revival by Cheryl A. Crowley makes this clear.

scholarly brilliance issues forth from your bottom firefly

At times in courtly Japanese poetry fireflies have been compared to the fires used to lure fish or the stars in the night sky. These creatures can stand as a metaphor for sexual passion.

In Jack London's Smoke Bellew in a chapter entitled The Stampede to Squaw Creek there is passage worth quoting: "Oh, I don't know. Mebbe that 'sa firefly ahead there. Mebbe they 're all fireflies — that one, an' that one. Look at 'em ! Believe me, they is a whole string of processions ahead."

The Continuum Encyclopedia of Animal Symbolism in World Art by Hope Werness gives lots of interesting information on fireflies - most of which we will cite here. In Japan hotaru were said to be souls, ghosts or warriors in battle. Werness, using Joly, relates the story of the Firefly Princess (Hotaru hime). In vying for her other insects were burned trying to bring her fire, but Hi Maro, the Firefly Prince succeeded. The author also discusses the role of fireflies in Mayan culture. The Death Lords told the Hero Twins [Hunahpu and Ixbalanque] they must keep their cigars lit all night. An impossibility. However the twins tricked the gods by placing fireflies at the end of their cigars to make them appear lit. Fireflies may also have been metaphorical references to the stars. T. Volker's version of the story of Hotaru hime is somewhat different. In it the winning suitor is a dragonfly - the symbol of Japan. (See our entry on tombo on our Tengu thru Tombo page.) In The Hidden Maya Martin Brennan gives a fuller detail (p. 179) of this American myth. The Heroes "...are compelled to play ball with the Lords of Death during the days and they are subjected to a series of ordeals during the nights. On the first night they are placed in the Dark House and given a torch and two cigars, which they are commanded to light and yet, impossibly, return in tact in the morning. The Twins outwit the lords by placing fireflies at the tip of their cigars and passing a macaw's tail as the flame of the torch."

There is a style of porcelain decoration adopted from the Chinese referred to as hotarude (蛍手) or firefly-style. When discussing Chinese porcelains it is referred to as the rice-grain patter. The hardened clay form is pierced through and then the openings are filled over with a translucent glaze giving each piece a special sense of delicacy - especially if the plate, bowl, cup or vase are of the kind known as egg-shell porcelain. Plique-a-jours is a similar technique, but with enamels.

And there is a firefly squid or hotaru-ika (蛍烏賊). It is the Watasenia scintillans or sparkling enope squid. Supposedly it is the most bioluminescent squid in the world which emits bright flashes at times - hence, the name. Tourist boats at Toyama take passengers out to watch these creatures as the near the surface and they flash their blue-white lights. There are different explanations for this behavior, but most modern sources say it occurs during spawning season. The photo below was posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Takoradee. What we don't know is how far back this name goes.

Since we don't have an image of the squid at night doing its hotaru thing we created the negative of the photo shown above to give you an inkling - get it? - of what it might look like in nature.

Just for good measure here is a part of a poem by Bessie Rayner Belloc (ベッシー Rayner ベロックス: 1829-1925) where the fairies are chasing fireflies. We know that it has absolutely nothing to do with Japan or its culture, but for now that is what got us chasing fireflies ourselves, metaphorically speaking.

But when the stars of the South shine bright, We chase the firefly thro' the night; When the tigers growl and the lions roar We fly over their heads and laugh the more

"There are many places in Japan which are famous for fireflies - places which people visit in summer merely to enjoy the sight of the fireflies. Anciently the most celebrated of all such places was a little valley near Ishiyama, by the lake of Omi. It is still called Hotaru-Dani, or the Valley of Fireflies. Before the Period of Genroku (1688-1703), the swarming of the fireflies in this valley, during the sultry season, was accounted one of the natural marvels of the country. The fireflies of the Hotaru-Dani are still celebrated for their size; but that wonderful swarming of them, which old writers described, is no longer to be seen there." This was replaced by Uji in Yamashiro. Every summer special trains run from Kyoto and Osaka to Uji, bringing thousands of visitors to see the fireflies. But it is on the river, at a point several miles from town, that the great spectacle is to be witnessed - the Hotaru-Kassen, or Firefly-Battle." Sometimes they appear "...to the eye like a luminous cloud, or like a great ball of sparks." At times it "...is said to appear like the Milky Way, or, as the Japanese people poetically call it, the River of Heaven." (Quoted from: Lafcadio Hearn: Japan's Great Interpreter: A New Anthology of His Writings 1894-1904 by Louis Allen and Jean Wilson, p. 190)

T. Volker noted that some people believed that the so-called firely-battles were reenactments of the souls of the Heike warriors. "The bigger specimens are called Genjibotaru, the smaller ones Heikebotaru." Later he writes: "After the battle of the river Uji in 1180, where his son was killed, Minamoto no Yorimasa, retreated to the Byodō, a temple in the neighborhood and performed seppuku. It is said that the soul left the body in the form of a swarm of fireflies."

Hotaru-Dani (火垂る谷); Hotaru-kassen (蛍合戦).

"Many persons in Japan earn their living during the summer months by catching and selling fireflies: indeed, the extent of this business entitles it to be regarded as a special industry.... From sixty to seventy firefly-catchers are employed by each of the principal houses during the busy season. Some training is required for the occupation. A tyro might find it no easy matter to catch a hundred fireflies in a single night; but an expert has been known to catch three thousand. The methods of capture, although of the simplest possible kind, are very interesting to see. [¶] Immediately after sunset, the firefly-hunter goes forth, with a long bamboo pole upon his shoulder, and a long bag of mosquito-netting wound, like a girdle, about his waist. When he reaches a wooded place frequented by fireflies - usually some spot where willows are planted on the bank of a river or lake - he halts and watches the trees. As soon as the trees begin to twinkle satisfactorily, he gets his net ready, approaches the luminous tree, and with his long pole strikes the branches. The fireflies, dislodged by the shock, do not immediately take flight... but drop helplessly to the ground, beetle-wise, where their light - always more brilliant in the moments of fear or pain - render them conspicuous. If suffered to remain on the ground for a few moments, they will fly away. But the catcher picking them up with astonishing quickness, using both hands at once, deftly tosses them into his mouth - because he cannot lose the time required to put them, one by one, into the bag. Only when his mouth can hold no more, does he drop the fireflies, unharmed, into the netting. [¶] Thus the firefly-catcher works until about two o'clock in the morning - the old Japanese hour of ghosts..." At that hour the fireflies move to ground and the catchers use a bamboo rake to stir the ground cover and get the fireflies to react and be caught there. A little before dawn the men would return home. ¶ At the shops theses insects are separated according to their luminosity. The brighter ones being the more valuable because they fetch higher prices. Some buyers selected them for summer parties. The cages ranged from the simplest to the most elaborate and beautiful. Since the captive fireflies had a high mortality rate they could still be redeemed financially when they were sold to specialists in the preparation of Chinese-style medicines. "Even today some curious extracts are obtained from them; and one of these, called Hotaru-no-abura, or Firefly-grease, is still used by wood-workers for the purpose of imparting rigidity to objects made of bentwood." ¶ Hearn believed some of the firefly medicines belonged more to the category of demonology than to therapeutics. "Firefly-ointments used to be made which had power, it was alleged, to preserve a house from the attacks of robbers, to counteract the effect of any poison, and to drive away 'the hundred devils'. And pills were made with firefly-substance which were believed to confer invulnerability..." sometimes as 'Commander-in-Chief Pills' or as 'Military-Power Pills'. (Ibid., pp. 190-2) Hotaru-no-abura (火垂脂).

Hotaru-gari (蛍狩り or ほたるがり) or firefly-catchin: "Anciently it was an aristocratic amusement; and great nobles used to give firefly-hunting parties..." (Ibid., p. 192)

Basil Hall Chamberlain in A Handbook of Colloquiel Japanese quotes Schopenhauer (ショーペンハウアー: 1788-1860), the German philosopher: "Religion is like a firefly. It can shine only in dark places." |

||

|

LINKS TO OUR OTHER INDEX/GLOSSARY PAGES Click on any of the pages listed below!

|

||

HOME

HOME