Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

Yakusha thru Z |

|

|

The molecular model on Lonsdaleite is being used as a marker for new additions from January 1 to May 31, 2021. The piece of sulphur posted at Wikimedia by Rob Lavinsky was used from June 1 thru December 31, 2020.

The detail from the diadem of

the Empress Eugénie |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Yakusha hyōbanki, Yama-ai, Yamaboko, Yamabuki, Yamabushi, Yamaotoko, Yamauba, Yamauba mono, Yamazakura, Yamazame,

Yanagi no mayu,

Yane-bune, Yang Gui-fei,

Yari, Yasakani no Magatama, Yashima Gakutei,

Yasuo Kume, Yatagarasu, Yatai,

Yatsuya guruma, Yōfūga, Yōga, Yōjutsu, Yōkai, Yōkai Attack: The Japanese Monster Survival Guide, Yoko, Yomeiri-bon, Yomogi-soba, Yōraku, Yoroi, Yōshi, Yoshisato, Yoshitsune, Yoshiwara, Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan, Yotaka, Yotsude-ami, Yotsume, Yozakura, Yüan (dynasty), Yūgao, Yuiwata, Yukata, Yuki, Yuki-Daruma, Yukimi dōrō, Yukiwa, Yumi, Yumiya, Yūrei, Zabuton, Zakoba, Zakuro, Zangiri-mono, Zarusoba, Zatō, Zendama akudama, Zori, Zōri tori, Zuishin and Zukushi

役者評判記, 山藍, 山鉾, 山吹, 山伏, 山男, 山姥, 山姥物,

山桜, 柳の眉, 屋根船, 楊貴妃,

洋風画, 洋画,

妖術, 妖怪, 洋紅,

源義経, 吉原,

雪見灯籠, 雪輪, 幽霊, 座蒲団, 弓, 弓矢, 雑魚場, 石榴, 残切物, 笊蕎麦,

座頭,

|

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Yakusha hyōbanki |

役者評判記 やくしゃ.ひょうばんき |

Annual actor critiques in printed form which appeared until c. 1890. |

|

Originally courtesans were rated on an annual basis and it was not a great leap to start doing so for actors too. The first such publications paid emphasis on the homoerotic allures of young male actors, but eventually covered the full range of actors. Samuel L. Leiter notes: "The contents of such books were likely to include descriptions of he actors' appearance, disposition, dancing ability, vocal quality, partying tastes, sexual proclivities, and so on, including examples of the actors' poetry and pictures of them and their mon [or crest].

This description sounds sneakily like the classified ads placed in the mostly 'adults only' alternative publications and on-line solicitations.

Leiter added: "In the early days the actors' looks and sex appeal were given more importance than their talents." I might add, that little has changed today. Many contemporary actors have better bodies and looks than skills and depth. But everyone knows that. (Quotes from: New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of kabuki jiten, 1997, p. 696)

Regis Allegre at Kabuki21 gives the last date for such books as 1890 while Leiter gives their terminus ante quem as 1877.

Regis Allegre has given us a more thorough explanation of this subject:

|

||

|

|

||

|

Yama-ai |

山藍

やまあい |

Leaves of the Mercurialis leiocarpa used to obtain a blue stain on the fabric aozuri. "In Japan, the leaves and rhizomes was used for dyeing in ancient days."

Quote and image was provided by Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. |

|

"I had given this matter some thought and, as I had asked Ono Tonomo-no-Suke Shigekata about it, he sent me an omigoromo. There were patterns on the jōe such as plum, willow, butterflies and birds, but one of its sleeves was missing. Mountain indigo (yama-ai) is called tōkotsusō, I hear, and is the berry of a shrub, but is now found among the wild plants that are used each year. Tōkotsusō is given different names in some dialects. I have heard country folk call its berry bishabo. Wild indigo (no-ai) is aohana. Sticking grass (tsukikusa) is so called because it prints on well (suritsuku). In old verse, yama-ai is also yamazuri, and no-ai is nozuri. Tsukikusa is still called tsuyukusa. It is a variety that is no longer used by dyers." Quoted from: Tendai Shoshin Roku Ueda Akinari (1734-1809), p. 143.

Tōkotsusō may be 透骨草. |

||

|

|

||

|

Yamaboko |

山鉾

やまぼこ

|

A festival float. Also, referred to as hikiyama (曳山) or festival floats. Members of a neighborhood association "who are in good physical condition are assigned by a steering committee made up of representatives of the older wealthier families in the community to build festival wagons (hikiyama). To be considered 'alive' or functioning, a wagon requires two leaders, two traffic negotiators, abundant decorations, and a continuous source of music. The hikiyama often carries structures upon which a yorishiro, or place suitable for a deity to alight is built. This usually takes the form of a mountain (yama) sculpted of papier-mâché. It is deemed an appropriate 'god-seat' since mountains, particularly impressive mountains, have been considered holy since earliest times. It is thought that in Japan 'sacred mountains' were originally designated as such because of their significance as sources of water for the surrounding farmland."

Quote from: :Matsuri: Japanese Festival Arts, by Gloria Granz Gonick, UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 2002, p. 45.

Right after I posted this entry I wrote to one of our great contributors to see if he had any print images of yamaboko. He didn't, but he did have these photos. Brilliant!, aren't they? The top one shows a detail of the float itself. Brilliant!

Properly speaking hikiyama (曳山) means 'mountain pulling' because they are moved by men using large, thick ropes. In the Kantō region these floats are called dashi (山車) which literally would mean 'mountain vehicle'. Ostensibly dashi are meant to be of a size intended to draw the attention of the kami. (See our entry on kami on our Kakuremino thru Ken'yakurei index/glossary page.) Dashi is supposedly derived from dasu (出) which means 'to stick out' among other things. |

|

Yamabuki |

山吹

やまぶき

|

Yamabuki or Japanese Rose is also known under the botanical name Kerria japonica.

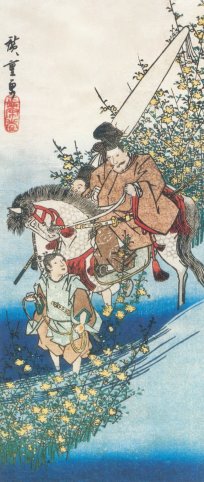

In the catalogue to the great Utamaro exhibition at the British Museum Timothy Clark describes a courtesan arranging a flowering kerria branch and notes "This is an oblique reference to the most common pictorial representation of the Ide Jewel River, which was a courtier crossing the river on horseback, with kerria blooming at the water's edge." (Quote from: The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, text volume, p. 117)

The detail of the image with the rider is by Hiroshige shows the poet Fujiwara no Shunzei (1114-1204) crossing the Ide Tama River inspired to write a poem about the yamabuki flowers clustered there.

こまとめてなを水かはんやまぶきの

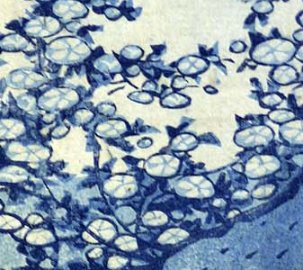

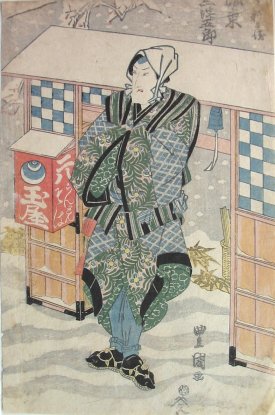

花のつゆそふ井での玉河 The image below that is a detail from a print by Kunisada - seen above. In the foreground is an actor. Behind him is an aizuri-e landscape with a relatively subtle reference to the crossing of the Ide Tama River. Here, of course, the flowers are printed all in blue, but the connection is clear. I want to thank my great friend Mike for sending me this image. 1

|

|

Yamabushi |

山伏 やまぶし |

Mountain ascetics |

|

Yamaotoko |

山男 やまおとこ |

Wild men who live in the mountains and seem not unlike yeti or bigfoot if one follows traditional descriptions. Carmen Blacker in her "Supernatural Abductions in Japanese Folklore" (published by Nanzan University, Asian Folklore Studies, Vol. 26, No. 2, 1967, p. 115) gives a full description as to their nefarious intents: "The tall, hairy difficult if not impossible to escape, were yamaotoko or 'mountain men'. These mysterious, semi human denizens of mountains, the belief in whom some Japanese folklorists think may have originated in an ancient and unfamiliar race of mountain people, are described fairly uniformly by woodcutters of various districts. They are very tall, with glittering eyes and long hair straggling down to their shoulders. Sometimes they are covered with leaves or tree bark instead of fur. These creatures, it will be noted, never take the child on entertaining journeys to strange lands and mountains. They carry it straight back to their lair in the mountains, there keeping it in strict durance as a servant or catamite. [Now there's a euphemism for you.] Women, it will also be noted, are kidnapped only by yamaotoko and for the sole purpose of becoming the wives of the creatures. They are never taken on the magic journey." (See also our entry on kamikakushi or spirit abductions.) |

|

Yamauba |

山姥

やまうば

|

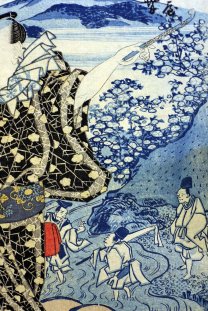

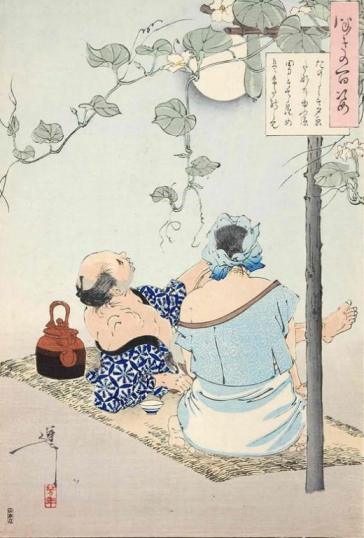

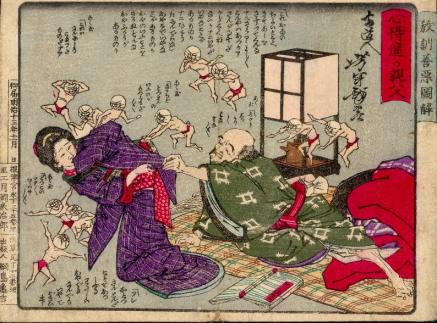

"Yamauba

was originally a female flesh-eating ogre who lived deep in the mountains,

but in the Edo period she was transformed into the mother or wet-nurse of

the strong boy Kintarō (Kidō-maru), who grew up to be the warrior hero

Sakata Kintoki, one of the four great retainers of Minamoto no Yorimitsu." Quote from: Demon of Painting: The Art of Kawanabe Kyōsai, by Timothy Clark, British Museum Press, 1993, p. 105. The top example to the left is a detail from a print by Kuniyoshi showing Yamauba in them more romantic mode of the Edo period. The one in the center is from a book illustration where she is shown as a truly frightening had. The Utamaro at the bottom portrays her as the doting mother.

|

|

Yamauba mono |

山姥物 やまうばもの |

"Mountain hag

play": "'Yamauba pieces' is the name given to the lineage of Kabuki dances

deriving from the concluding scene of Chikimatsu Monzaemon's puppet play

Komachi Yomamba." This genre became a motif in print form for the

expression of love of a mother for a child. Quote from: The

Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum

Press, London, 1995, text volume, p. 224. Chikimatsu's Yamauba "...appears as a wild old woman with long hair and ragged clothes who dances opposite the infant Kintarō." Quote from: Quote from: Demon of Painting: The Art of Kawanabe Kyōsai, by Timothy Clark, British Museum Press, 1993, p. 105. |

|

Yamazakura |

山桜

やまざくら |

One of several woods used to print woodblocks, but this was the most common and popular one of the ukiyo period. Referred to as the wild mountain cherry tree or Prunus serrulata in the West. 1

Long before the mountain cherry tree was used for ukiyo-e prints it was a favorite of the poets. In one of the greatest compilations, One Hundred Poems by One Hundred Poets, the Hyakunin Isshu (百人一首), poem #66 by Saki no Daisōjō Gyōson (前大僧正行尊: 1055-1135):

On a mountain slope,

The image shown above is courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. He identifies this tree using the synonymous term Prunus jamasakura. |

|

A wild cherry tree are mentioned in chapter 28, The Typhoon, of The Tale of Genji. Although the term used, kabazauka (かばざくら) or 'birch cherry', is now obsolete all three major English language translations give it as some slight variation of a flowering mountain cherry tree or yamazakura. The setting for Nowaki (野分き) or The Typhoon - Yūgiri arrives right after a storm to visit his father, Prince Genji, and gets his first glimpse of Murasaki. Below are partial quotes from Waley, Seidensticker and Tyler.

The 1929 translation (1993 edition) by Arthur Waley: "There, in full view of anyone who came along the corridor, reclined a lady of notable dignity of mien and bearing would alone have sufficed to betray her identity. This could be none other than Murasaki. Her beauty flashed upon him as at dawn the blossom of the red flowering cherry flames out of the mist upon the traveller's still sleepy eye. It was wafted towards him, suddenly imbued him, as though a strong perfume had been dashed against his face. She was more beautiful than any woman he had ever seen."

The 1976 translation (1992 edition) by Edward Seidensticker: "He stopped to look at the women inside. The screens having been folded and put away, the view was unobstructed. The lady at the veranda - it would be Murasaki. Her noble beauty made him think of a fine birch cherry blooming through the hazes of spring. It was a gently flow which seemed to come to him and sweep over him."

The 2001 translation by Royall Tyler: "There was no mistaking her nobly warm and generous beauty: she looked like a lovely mountain cherry tree in perfect bloom, emerging from the mists of a spring dawn. The breath of her enchantment seemed irresistibly to perfume his face even as he watched. She was nothing less than extraordinary."

Are all of these translations related to a poem by Ki no Tsurayuki (紀贯之: 872-945) listed as Kokinshū (古今集) no. 479:

A fleeting glimpse as of mountain cherries through the thick veil of spring mists I scarcely saw the one who captured my heart

In about 1504 Sōchō (宗長: 1448-1532) who was about to build an isolated hut wrote a poem again linking the concept of cherry blossoms with haze:

The mountain cherries - how my longing for them is enhanced by the haze!

Quoted from: Song in an Age of Discord: The Journal of Socho and Poetic Life in Late Medieval Japan by H. Mack Horton, p. 37.

In 1778 Yosa Buson (与謝蕪村: 1716-1783) wrote a particularly poignant and touching verse:

Is it blossoming because of lonliness? the mountain cherry

The wild cherry tree and its blossoms seem to have a connection with things military. One book published in the West in 1902 referred to the yamazakura as an "...emblem of Japanese knighthood." An oft cited poem by Motoori Norinaga (本居宣長: 1730-1801) reads: "If one should inquire of you concerning the spirit of a true Japanese, point to the wild cherry-blossom shining in the sun." Basil Hall Chamberlain in his Things Japanese quotes this - as do many others - and adds this proverb: "The cherry is the first among flowers, as the warrior is first among men." The cherry blossom is preferred over that of the prunus, i.e., plum because the latter is thought to be of Chinese origin. One of the units of kamikaze pilots during World War II was named after the yamazakura mentioned in Norinaga's poem.

The flowers of the yamazakura could serve as a symblol of the impermanence of life. When the Heike warriors were forced to flee the capital they said their sincere and tearful goodbyes to people they were close to like the abbot of Ningi. One of the priests, Gyōkei (行慶), composed a poem commemorating their departure - "...a poem which echoes the dominant theme of the Heike - that all that exists in the world is doomed to pass away:"

Oh how pitiful it is That mountain cherry trees Whether they be young or old, Whether they blossom early or late, Must in the end shed their flowers.

"...the Taira warriors [i.e., the Heike] are being compared with the cherry blossoms. Elegant and refined they may be, but in the end they too are destined to fall." (Source and quotes from: The Russo-Japanese War in Cultural Perspective, 1904-05, edited by David Wells and Sandra Wilson, p. 54)

As should be clear by now an entire web site could be devoted to poetry and yamazakura. We have only touched the tip of the iceberg here.

There are a considerable number of different cherry tree varieties in Japan. That is why "...in 1984 two Americans... decided to untangle the thicket by dividing the flowering cherries into two groups: Yama-zakura, or mountain cherries for the wild species, and Sato-zakura for village cherries or the cultivated plants..." (Quoted from: Enduring Roots: Encounters with Trees, History, and the American Landscape by Gayle Samuels, p. 74)

While modern hybrids, that is since the time of the Meiji period, have become the standard form recognized in Japan and around the world for what we think of when we muse about flowering cherry trees, it is the yamazakura that in backwoods areas such as Kyushu (九州) "...are still seen highlighting the forests like dabs of paint." (Quoted from: Hitching Rides with Buddha by Will Ferguson, p. 72)

Rebecca Salter in her book on Japanese Woodblock Printing (p. 15) gives quite a nice description of this wood: "Japan was particularly fortunate in having plentiful supplies of yamazakura... [This tree] has few flowers or fruit and the pith on the inside lining of each annual growth ring is the same density as the ring itself. The best planks come from trees grown on mountains near the sea, particularly on the Izu peninsula near Tōkyō. The grain from these trees was fine and even, the wood was relatively easy to carve yet highly cohesive and did not splinter. Cherry from too far north in Japan was considered tougher to carve and did not take the colour well. ¶ Supplies of yamazakura are however, now diminishing rapidly." Early on this wood was used for carving texts which Salter distinguishes from similar Chinese carvings. In Japan cursive was preferred over block lettering and only the best wood would do for such printings. |

||

|

|

||

|

Yamazame |

山鮫

やまざめ

|

Literally a mountain shark, a crocodile-type creature.

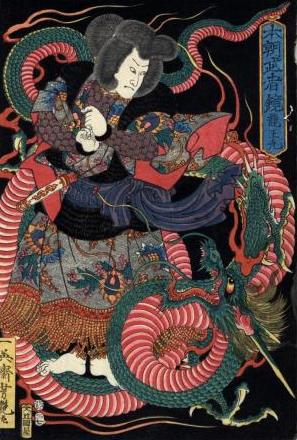

The image to the left and above are both by Kuniyoshi. The one to the left is from the British Museum and dates from ca. 1843. The one above is from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and is dated to ca. 1830. The text on that print makes reference to the 山鮫 yamazame. |

|

Yanagi |

柳

やなぎ

|

Willow tree: In an article entitled "Chinese Flower Symbolism" by Alfred Koehn in the Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 8, No. 1/2, 1952, p. 131 it states: "As a symbol of Spring and Meekness, the Willow has inspired poets and painters; they are fond of using it as an emblem of Femininity. Popular belief holds that the Willow exercises power over evil spirits. Tombs are swept with it, and its branches are fixed to the gates of houses as an omen of Good Luck."

Merrily Baird (Symbols of Japan, p. 66) adds that the Chinese also believed that it could prevent blindness and purify. Baird notes that in Japan that yanagi "...is commonly represented with water, snow, swallows, or herons. A branch of willow (yoshi) is one of the attributes of Buddhist deity Senju Kannon [観音] (Thousand-Armed Kannon), who is said to use the branch to sprinkle the nectar of life contained in a vase."

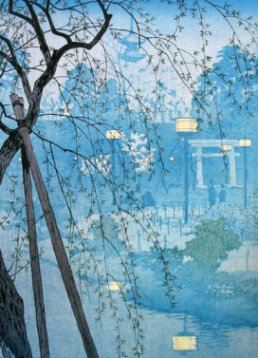

The top two photos were graciously supplied by Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. The bluish print detail is from a work by Kasamatsu Shirō (1898-1991: 笠松紫浪). The title is given as "Evening Rain at Shinobazu Pond" (夜雨不忍池) from 1932.

Koehn in his Japanese Flower-Symbolism from 1939 noted that the display of a willow branch which has been twisted to form a circle somewhere along the branch at a farewell gathering was meant to convey "...wishes for a safe return."

In China the custom was different, but its similarities seem clear. "Willow branches were commonly snapped when parting form a firend, 'willow' (liu) being homophonous with 'stay' (liu). Since officers in Chang-an were constantly being sent off in military service or to civil posts in the provinces, the willows by the royal moat tended to have more snapped branches than most." Quote from: An Anthology of Chinese Literature: Beginnings to 1911, edited and translated by Stephen Owen, W. W. Norton & Company, 1996, footnote, p. 394.

Mock Joya adds much to our knowledge of willow lore. A 'willow waste' described a graceful, slender woman.

On New Year's Day "...the Emperor would exclaim: 'Under the yuzu [柚] (citron) tree? to which the Empress replied 'Medetashi' (happy)." Since the yuzu was a royal prerogative commoners substituted the yanagi for this ritual. "It is probably that from this ancient custom of using this happy expression on New Year's day, chopsticks made of willow wood are still used during New Year celebrations even today." These chopsticks are used exclusively and burned afterwards." (Source: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 378-9)

|

|

Years ago I was told or I read that the weeping willow was a symbol of prostitution in ancient China. I have been unable to confirm this and have had experts I respect disagree with me. Supposedly brothels - both legal and illegal - prospered along waterways where this type of tree was commonly seen. In 1589 one of Hideyoshi's retainers opened the first licensed district in Kyōto. At the entrance to this district were two huge willow trees. It was called Yanagi-no-baba, but came to be called Yanagimachi (柳町) or "Willow Street". There was another Yanagimachi in Edo, J. E. de Becker this one "...did not derive its title from the one in the Western city." (Source and quote from: Yoshiwara: The Nightless City, by J. E. de Becker, Frederick Publications, 1960, p. 2)

The references below all come from an article entitled "Kung Hsien's Self-Portrait in Willows, with Notes on the Willow in Chinese Painting and Literature" by Jerome Silbergeld published in Artibus Asiae in 1980 (Vol. 42, No. 1, pp. 5-38).

As early as the Han dynasty (206 B.C. to 220 A.D.) in China the willow was used "...as a metaphor for feminine beauty, romantic and often erotic."

By the T'ang dynasty (618 to 970) the elegant willow was being compared to a woman's slender waist. Later Po Chü-i wrote about Ming-huang's yearning for Yang Kuei-fei. Here a woman's eyebrows are likened to the willow. (See our entry for yanagi no mayu below. Clearly the Japanese borrowed this Chinese model.)

Home again, the pools and gardens were all just as before- The hibiscus of the T'ai-i Pool, the Wei-yang Palace willows. But the hibiscus were like her face, the willows like her eyebrows, And facing them, what could he do but cry.

Even the drooping branches came to be compared with the delicate gossamer clothing of a beauty. In the anthology "Three Hundred T'ang Poems" the willow is mentioned more than any other plant. In the capital cities of Lo-yang and Ch'ang-an famous courtesans and great beauties adopted surnames meaning Willow or if not that nicknames using the same references. "The nation's finest gay quarters were in Ch'ang-an, and one of them must have been a willow-lined district known as the Chang-t'ai or Chang Terrace. The phrase "Chang-t'ai Willow," used in reference to these courtesans..." One famous poet wrote about his lover, 'the Willow of Ch'ang Terrace', who fled in turbulent times to a nunnery only to be abducted by an enemy general. The poet wrote of her:

Is the fresh green of former days still there? No, even if the long branches are drooping as before, Someone else's hand must have plucked them now!

"Willow Village, Flower Street" became synonymous with any brothel district anywhere. In Mathew's Chinese English Dictionary (p.589) a willow lane was a reference to brothels. And the expression "sleeping in the flowers, lying among willows" [is] simply translated as "passing the nights in the brothels..."

In footnote 66 Silbergeld notes other attributes ascribed to the willow by the Chinese, but not mentioned in the poetry of Kung Hsien: "...namely their common use as an herb of healing (containing a natural form of aspirin), as a ritual object in Buddhist purifi- cation rites, as a charm for warding off evil spirits, and as an aid in spirit-conjuring..."

One Confucian scholar likened a fondness for willows with dissipation and decline.

Alfred Koehn wrote: "Popular belief holds that the Willow exercises power over evil spirits. Tombs are swept with it, and its branches are fixed to the gates of houses as an omen of Good Luck."

"A code of sexualized symbols existed that almost all the inhabitants of Edo would have instinctively understood. Red, symbolizing the transition to womanhood, was considered an erotic colour. A glimpse of bare feet against a line of crimson silk undergarment was considered electrifying. The willow tree, seen growing outside and within the gates of the Yoshiwara, was a symbol of prostitution." Quoted from: Tokyo A Cultural History by Stephen Mansfield, p. 35. |

||

|

|

||

|

Yanagi no mayu |

柳の眉 やなぎのまゆ |

Willow eyebrows - a metaphor for a beautiful woman. (Source: Jewels of Japanese Printmaking: Surimono of the Bunka-Bunsei Era 1804-30 by Joan Mirviss and John Carpenter - cat. entry #16, p. 64)

In Chinese this metaphor reads: 柳眉杏眼 - willow eyebrows and almond shaped eyes.

In a popular Ming drama, The Peony Pavilion (Ch: 牡丹亭), from 1598, a beautiful young woman is painting a self-portrait to leave for her parents because she is about to be forced into an unwanted marriage. The text describes her features:

This is quoted from the doctoral thesis of Li Guo at the University of Iowa in 2010.

During the T'ang Dynasty Li Shang Yin (813-59) wrote about 'willow eyebrows'. |

|

The link between eyebrows and willows must go back to the earliest contacts between the Chinese and Japanese courts. "Willow charcoal is eyebrow charcoal, a fancy Chinese term apparently used to mean simply 'willow.' Or perhaps the title underlines the association of willow leaves with graceful eyebrows and hence with beautiful women, suggesting that Yakamochi [compiler of the Man'yōshū] is thinking of the ladies of the capital as much as of its willow-lined streets. This apparently remote possibility, first suggested by the eminent early Man'yo scholar Keichu, is somewhat bolstered by the poem's resemblance to one of the anonymous songs of Book X: [10:1853]

Quoted from: A Warbler's Song in the Dusk: The Life and Work of Ōtomo Yakamochi (718-785) by Paula Doe, p. 156.

Yakamochi also uses conventional Chinese metaphors common in Six Dynasties love poetry, such as in the following poem from his years in Etchū, where he likens a woman's eyebrows to willow leaves and her skin to rosy peach blossoms: [19:4192]

Ibid., p. 49

Cho Kyo wrote on page 77 of The Search for the Beautiful Woman: A Cultural History of Japanese and Chinese Beauty: "As willow eyebrows (liumei) was a fixed phrase referring to a beautiful woman in literature, so were, in art too, long eyebrows with a gentle curve a metaphor for a favored countenance." |

||

|

|

||

|

Yane-bune |

屋根船 やねぶね |

Covered pleasure boat - In 1904 Frank Brinkley wrote in his Japan [And China]: Its History, Arts and Literature that Edoites in May and June would go out in these boats at low tide to party, picnic and gather sea shells. "These pleasure-seekers launch themselves in the favourite vehicle of Tokyo picnics, the yane-bune, — a kind of gondola, — and float seaward with the ebbing tide, singing snatches of song the while, to the accompaniment of tinkling samisen, or of that graceful game ken, so well devised to display the charms of a pretty hand and arm. Such outings differ in one important respect from the more orthodox picnics of Tōkyō folks, — the visits to plum-blooms, cherry-blossoms, peony beds, chrysanthemum puppets, iris ponds, and river-openings. They differ in the fact that there is no display of fine apparel."

See also our entry on yakata-bune.

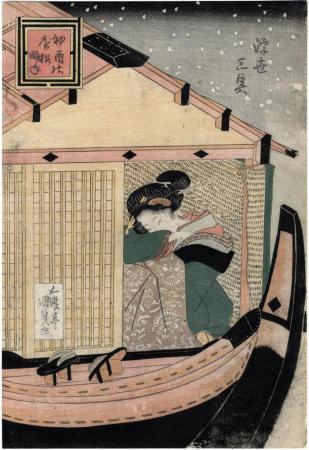

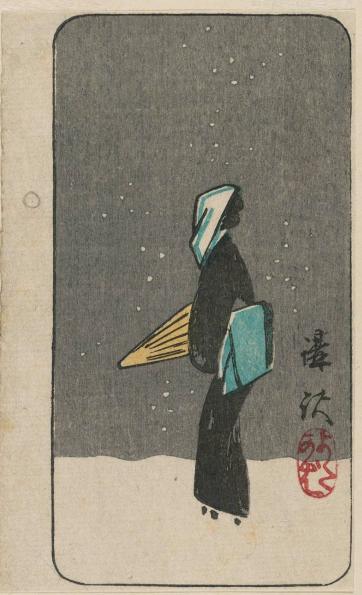

The image to the left is from the Lyon Collection. It shows a woman in a covered pleasure boat in winter. It has yanebune in the title. Click on it to see more information. |

|

Yang Gui-fei |

楊貴妃

ようきひ

|

Great beauty (719-56) who was the love object, i.e., main squeeze, heart throb, honey pie, of the T'ang dynasty emperor Xuan Zong. Romantic tales of this tragic love affair blame the collapse his empire on the emperor's neglect of his duties. Similar to the misconception that Rome burned while Nero fiddled here it is Xuan Zong's obsessive infatuation with Yang Gui-fei which leads to disaster.

Prior to modern historiography the general focus of historical events was placed on individuals rather than the larger paradigms such as economics, etc.

"Emperor Xuanzong's concubine Yang Guifei almost brought him down with her, yet, she was redeemed in popular memory because of her tragic end, and was even deified in Japan as an avatar of the Bodhisattva Kannon. According to one tradition, Xuanzong even came to Japan looking for her, and eventually found her at Kumano, a place assimilated to the Daoist 'Island of the Immortals,' Penglai."

Quoted from: The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender, by Bernard Faure, published by Princeton University Press, 2003, p. 204.

|

|

Murasaki Shikibu, the author of "The Tale of Genji" was born in 978? at a time when it only made sense to look at personalities as the movers and shakers. We know that she was educated and must have been well versed in Chinese literature. At the very beginning of "The Tale of Genji", Kiritsubo (The Paulownia Pavilion), makes this eminently clear. The Japanese emperor falls in love with and dotes on a minor court beauty.

"From this sad spectacle the senior nobles and privy gentlemen [of the Japanese emperor's court] could avert their eyes. Such things had led to disorder and ruin even in China, they said, and as discontent spread through the realm, the example of Yōkihi [Yang Gui-fei's Japanese name] came more and more to mind, with many a painful consequence for the lady herself, yet she trusted in his gracious and unexampled affection and remained at court.... His majesty must have had a deep bond with her in past lives as well, for she gave him a wonderfully handsome son [Genji]."

Quote from: The Tale of Genji, by Murasaki Shikibu, translated by Royall Tyler, published by Viking, 2001, vol. 1., p. 3.

In all of the versions of the story of Yang Gui-fei the Chinese emperor's concubine has to die to save the state. Whereas the analogy is not one to one Genji's mother dies young and the emperor's grief is inconsolable. He neglects almost everything, but his loss. Murasaki Shikibu's erudition is made clear in her allusion to the Chinese poem, "A Song of Unending Sorrow", by Bai Juyi's (772-846). In it Xuan Zong sends a Taoist priest to find the soul of Yang Gui-fei. The priest returns with a message declaring that long after the earth and the heavens cease to exist the lovers' grief will be eternal. [Bai Juyi can also be spelled Po Chü-i and Bo Ju-yi.]

The story of Yang Gui-fei would have been a favorite theme in the arts of the love-loving Japanese based on Bai Juyi's poem alone, but the inclusion of this theme at the beginning of "The Tale of Genji" must have cinched its place as a Japanese motif.

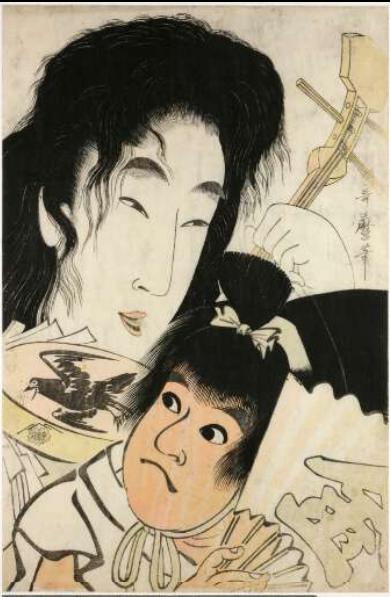

The doctored and cropped images to the left are from a print by Toyokuni I [top] and Utamaro. Note that in the bottom one both the Chinese emperor and his lover are playing on the same flute.

One other note: T'ang dynasty and later Chinese renditions of Yang Gui-fei show a full-bodied, size 16-18, Rubensesque woman. The Japanese images are generally much more svelte.

During the Ming dynasty the artist and connoisseur Wên Chên-hêng created the earliest fully extant guide for the "Calendar for the displaying of scrolls". It starts at New Year's morning when he suggest the hanging of Sung dynasty paintings of the Gods of Happiness or images of the Sages of old. "On the eighth day of the fourth month, the birthday of Buddha, you shold display representations of Buddha by Sung and Yüan artists, or Buddhist pictures woven in silk dating from the Sung period." And so it goes from event to event until "the eleventh moon [when] there should be paintings of snow landscapes, winter plum trees, water lilies, Yang Kuei-fei indulging in wine, and suchlike pictures."

Source and quote from one of my favorite books: Chinese Pictorial Art, by R. H. van Gulik, Hacker Art Books, 1981, pp. 4 & 5. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

矢の根

|

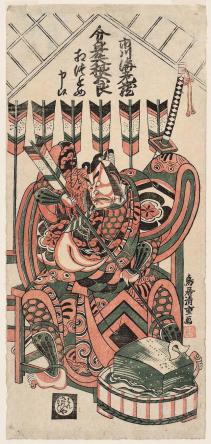

Arrow-sharpening scene - "Frequently depicted in actor prints, usually featuring one of the formidable Ichikawa Danjūrōs who incorporated this piece into their family collection (kabuki juhachibari), the arrow-sharpening scene from the play Yanone is one of the most universally recognized images to emerge from Kabuki. Soga Gōrō, polishing his arrows with a whetstone at his feet and with a huge arrow in his hand, full of bravado and pent-up energy, epitomized the aragoto acting style of Edo Kabuki." Quoted from: Ningyo: The Art of the Japanese Doll by Alan Scott Pate.

The 1754 image above to the left is by Kiyoshige and is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The one above is by Kiyomitsu II and is also from that collection. The Kunisada to the left below is from the collection of Waseda University. The Kunisada below is from the collection of Ritsumeikan University. Notice particularly the wigs worn by these last two entries.

|

|

Yaoya |

八百屋

やおや |

Greengrocer - This term is important because it plays an important part in both kabuki and puppet theater. In one caae it is the story of Oshichi as told by Scholten Japanese Art: "The role of Oshichi is based on the true story of Yaoya Oshichi, the 16 year old daughter of a vegetable-seller who in 1681 fell in love with a young priest who she met when she went to his temple to escape a large fire in Edo. In a misguided attempt to see the priest again, Oshichi set fire to her own house, which spread and destroyed a large area of the city. She was arrested and convicted of arson; her punishment was death by fire. Her story became the basis for several kabuki plays."

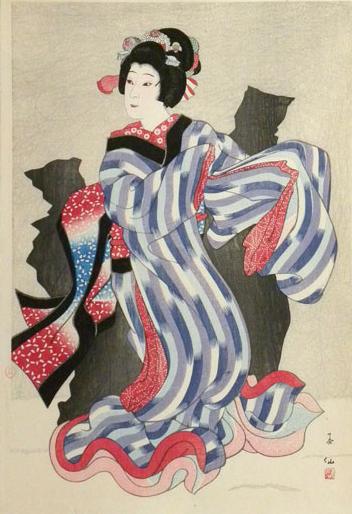

To the left is a Natori Shunsen of Nakamura Jakuemon as Oshichi in a puppet play. It dates from 1927. |

|

Yari |

槍

やり |

Spear: According to the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan (vol. 1, p. 89, entry by Ogasawara Nobuo) "There are two types of Japanese spears, identical in function: the hoko and the yari." The distinction between the two was based on how the spearhead was attached to the wooden shaft (vol. 7, p. 224, entry by Tomiki Kenji).

The yari came into common use in the 14th century. The Mongols had used this type of spear during their attempted invasions of Japan in the 13th century. "The yari commonly has a double-edged blade or head ranging in size from ...12 to 29 [inches]..." generally. There are several variations on the design including forked spearheads with two or more prongs.

The image to the left is a detail from a book illustration by Yoshitoshi.

In A Book of Five Swords and a Scroll (2007, p. 52) by Stanford D. Carman it says: "The Yari on the other hand were more in the style of spears and mounted on poles somewhere between 15 and 18 feet in length. This length was usually determined by how the Daimyo wanted his Ashigaru (foot soldiers) to be armed, and his fighting strategies/tactics." Note that ashigaru also used other weapons. |

|

Yasakani no Magatama |

八尺瓊の勾玉 やさかにのまがたま |

The grand jewel or string of jewels which are one of the three parts of the Imperial regalia, along with the sacred sword and the mirror. In the KojikiI Amaterasu orders her grandson to cross the Bridge of Heaven to go down to the earth and rule the area of Izumo. She gives him the three sacred items which gave legitimacy to the Imperial family. |

|

Yashima Gakutei |

八島岳亭 やしま.がくてい |

Artist (1786? - 1868) |

|

Yasuo Kume |

Author of Tesuki Washi Shuho: Fine Handmade Papers of Japan 1 |

|

|

Yatagarasu (also yata no karasu) |

八咫烏

やたがらす |

"The mythical... Sun-Crow, had formerly a shrine in its honour." Quote from: Shinto: The Way of the Gods by W. G. Aston

Said to have been sent by Amaterasu to guide the armies of the emperor Jimmu.

Henri Joly links it to the 3-legged crow of Chinese lore.

The first character of yatagarasu is 八 which normally means 'eight.' Aston wrote in a footnote on p. 52: "Eight - in Japanese yatsu. This word is here used as a numeral. But in many places in the old Japanese literature it must be taken in what I regard as its primary sense of 'many,' 'several,' as in the word yatagarasu - the many-handed crow - which had really only three claws. In Corean the word yörö, which means many, is, I think, the same root that we have in yöi, ten - words which are probably identical with the Japanese yatsu. The Japanese word yorodzu, myriad, belongs to the same group."

Detail of an illustration from a Santo Kyoden yomihon from 1806. Waseda University Library. |

|

"Of the various birds appearing in Japanese myth, the most familiar is probably the giant crow, Yatagarasu 八咫烏, who guides the army of Kamu Yamato Iwarebiko 神日本磐余彦 (henceforth referred to by his more commonly used name, Jimmu 神武) from Kumano 熊野. When Jimmu arrived at Kumano, a large bear appeared, and for that reason all members of the party fainted and fell down. The deities of Kumano had stood in their way, blocking their path. According to the Kojiki, when Jimmu awoke there stood before him Takakuraji 高倉下 of Kumano, who then relates the words told him in a dream by Takagi no Kami 高木神...

|

||

|

|

||

|

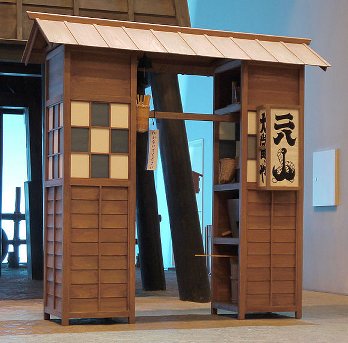

Yatai |

屋台 やたい |

A booth or stall. Now a food cart. Sometimes called a yatai-mise (屋台店) which is generally translated as 'stall' or 'stand'.

"Foods cooked on teppan in everyday life are usually fast foods, e.g., konomiyaki, whole cuttlefish on a skewer, dried fried noodles (yakisoba), meant to be eaten while standing in front of the shop, or most likely, a mobile kiosk (yatai)." (Quoted from: The Essence of Japanese Cuisine: An Essay on Food and Culture by Michael Ashkenazi and Jeanne Jacob, p. 95)

"Tempura was a popular street food already in the Edo period, cooked and served on bamboo skewers, and sold from small mobile stalls (yatai)." (Ibid., p. 92)

The image to the left is from a Toyokuni I print of a kabuki play scene. Click on it to go to page devoted to it and read about the noodles sold at such stands.

Yatai can be translated literally as 屋 'seller' plus 台 'stand'. 屋 can also mean roof and this is important. See our entry on fukinuki yatai on our Fu thru Gen page. |

|

"The earliest recipe for the modern version of tempura is found in Threading Together the Sages of Verse (Kasen no kumi'ito), published in 1748: 'Tempura is any fish covered with the flour used for udon and then fried in oil. However, when making chrysanthemum leaf tempura as described earlier, or using burdock, lotus root, Chinese yam [nagaimo], and other vegetables, soak the vegetables in water and soy sauce and then daub them with the flour. This is a good way to make snacks [sakana]. Things rolled in kudzu flour and then fried are also quite good.' ¶ Within decades this type of tempura became a popular fast food; it was sold in numerous stands (yatai) in Edo by the 1770s." Quoted from: Food and Fantasy in Early Modern Japan by Eric Rath, p. 105-6

The image shown above is a trimmed version of a photo posted at wikimedia by Drypot.

There is a good description of the modern yatai in Japanese Landscapes: Where Land and Culture Merge (p. 38 ff.): "Yatai (movable street stalls that sell food and drink) are another expression of compactness. At shrine or temple festivals, in public parks, on side streets near railway stations, in amusement centers, on riversides, and in the alleys of densely populated quarters, yatai are common elements of the landscape. From these popular wooden restaurants-on- wheels, steaming-hot delicacies are served with sake or beer. A yatai is a two- or four-wheeled handcart to which have been added the basic facilities required for serving food and drink. Handles for pulling it slide ingeniously into the body framework when not in use. At the rear, storage compartments rise up to support a solid roof. In these are kept dishes, bottles, food ingredients, sauces, condiments, fuel, and other supplies. Chopsticks, skewers, knives, and cooking utensils are available in a drawer at the front and between the handle shafts. The table for customers is a waist-high wooden surface into which are recessed either a hot plate or a copper-lined receptacle for soup heated from beneath. The compact yatai stalls provide additional functional space and are dear to the hearts of the Japanese, despite changing food fashions and modern innovations."

Under the heading of "Black-market Noodle-Vending" in Japanese Foodways, Past and Present (p. 194) it says: "As the Americans imported sizeable amounts of lard and flour, which Japanese authorities regulated less stringently than rice, noodle soups became a food more easily to obtain than rice for most urban Japanese. A notable increase in noodle soup sold at small yatai occurred as a result of a swell in open-air food vending, despite a prohibition against all such activity between July 1, 1947, and February 15, 1950, stipulated by the Emergency Measures Ordinance for Eating and Drinking Establishments (inshoku eigyō rinji kiseihō). Culinary scholar Okumura Ayao notes that the Shina soba and gyōza dumplings sold at the yatai carts became increasingly popular in the immediate postwar period because of their perceived nutritional value in providing stamina."

In Amazing Japan!: Why Japan is One of the World's Most Intriguing Countries! (pp. 49-50) there is a section that says this is the first nation to have created fast foods. "The success of the yatai at shrines led to their proliferation at other locations where crowds gathered, including sumo wrestling matches and cherry blossom viewing." Later "This extraordinary phenomenon [i.e., the growth of Buddhist temples] resulted in an equally impressive increase in the number of yatai in the country. The proliferation of courtesan districts during the Tokugawa shogunate era (1603-1868), also contributed to the number of yatai."

Yatai appear in quite a few Japanese prints. Off-hand we can think of examples by Hiroshige and Kunisada. Below is one such example, by the latter, from the Lyon Collection. A bijin, it would appear, is out for a summer stroll at a fair set up right outside of a temple shrine. The blue and white checkered pattern is a dead give-away. Click on the image to go to the page devoted to this print. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

矢立

やたて |

Portable brush and ink case -

|

|

Yatsuya guruma |

八つ矢車 やつやぐるま |

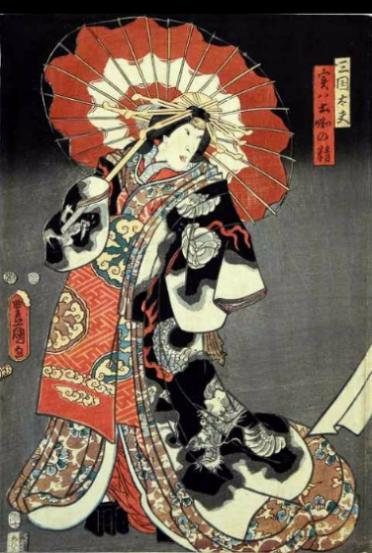

A crest or mon of a wheel made of eight hawk feathered arrows. This was the crest of the actors named Nakamura Tomijūrō. The image to the left is the center panel from a Toyokuni III triptych in the Lyon Collection. It shows Nakamura Tomijūrō II as an onnagata carrying an umbrella with his identifying crest. Click on the image to see the whole triptych. |

|

Yōfūga |

洋風画 ようふうが |

"Western-style painting (yofuga), an Edo-period artistic movement, refers to Japanese use of Western painting techniques including perspective, realism, and tonal variation. Western-style paintings might employ oil paints or use traditional Japanese pigments. Hiraga Gennai (1728–79), a Western learning scholar, is credited with starting this movement. He spent time in Nagasaki studying Dutch and Western science, and at the same time learned Western painting techniques. After moving to Edo, he introduced Western painting to his circle of like-minded intellectuals. Of particular note among those introduced to Western-style painting was Shiba Kokan (1738–1818) who expanded the study of Western painting styles and techniques. His paintings were oils on silk and included use of single-point perspective and some European themes." Quoted from: Handbook to Life in Medieval and Early Modern Japan by William E. Deal, p. 295. |

|

Yōga |

洋画 ようが |

Western style painting (or Western painting itself): "In practice, yōga is a form of painting created by using Western media, typically oil, on canvas. Broadly speaking, the term refers to works created in Western media in Japan after the late Edo Period as well as the entire tradition of Western painting. In the strictest sense, yōga means oil painting executed in Japan after the Meiji Period. Painting created using Western materials and/or techniques from pre-Meiji Japan is called yōfūga (literally, `Western-mode painting')." ¶ Western painting techniques were first introduced to Japan along with Christianity in the late sixteenth century and practised until the early seventeenth, when the country entered its isolationist period. A second wave of interest came with the expanding enthusiasm over Dutch studies, particularly science, in the late eighteenth century. Scientific perspective and modelling, both powerful tools for rendering the subject realistically, captivated the imagination of pre-Meiji yōfūga practitioners as well as traditional painteres; the fascination with realism (shajitsu) continued to the late nineteenth century, among early yōga artists such as Takahashi Yuichi, and well into the twentieth century. The Meiji government even deemed the study of yōga a utilitarian necessity in attaining the national goal of Westernisation." Quoted from: Encyclopedia of Contemporary Japanese Culture, 578. |

|

Yōjutsu |

妖術

ようじゅつ |

The magical arts -

The image to the left is from the Lyon Collection. It shows the wizard Ryūōmaru (龍王丸) doing his thing. Above is a detail from that print which shows the placement of his hands which empower his invocations. |

|

Yōkai |

妖怪

ようかい |

A ghost, demon, monster, goblin or specter.

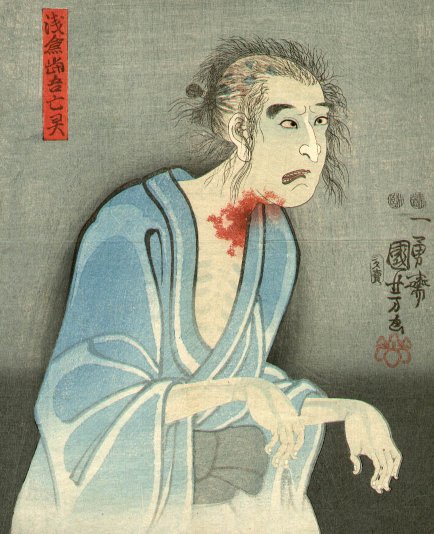

The image to the left of the bloody ghost is a detail from a print by Kuniyoshi and was sent to us courtesy of E. - one of our favorite correspondents. Creepy isn't it. In a larger detail you could see the disgusting sores on the scalp of the ghost. Maybe later. By the way, in the full sized print the ghost appears to float through the air just like the poltergeist in their eponymous movie.

The figure represents Ichikawa Kodanji IV as a Ghost of Sakura Sogorō.

In Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese Monsters and the Culture of Yokai the author, Michael Dylan Foster, traces the history of yōkai beliefs. ",,,during the Edo period... particularly from the 1660s through the 1780s, when yōkai made a name for themselves in both serious encyclopedic taxonomies and playful illustrated catalogs. The second moment came during the Meiji (1868-1912), especially in the 1880s, as yōkai underwent a radical reevaluation in light of Western scientific knowledge. The third moment encompassed the first decade of the twentieth century through the 1930s, when yokai were refigured as nostalgic icons for a nation (and individuals) seeking a sense of self in a rapidly modernizing world. And the fourth came in the 1970s and 1980s, as Japan asserted a new identity after its rapid recovery from the devastation of World War II." |

|

Foster also notes that the term 'yōkai' has not always been in general use: "Though yōkai is presently the word of choice in contemporary discourse on the subject, other terms are also invoked, such as bakemono, the more childish obake, and the more academic-sounding kaii genshō. In late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century Japan, however, yōkai remains the term most commonly associated with the academic study of these 'things.' Historically the popularity of the word is relatively new. Although it has semantic roots in China and can be found in Japan as early as the mid-Edo-period work of Toriyama Sekien... it did not develop into the default technical term until the Meiji-period writings of Inoue Enryō... who consciously invoked it to describe all manner of weird and mysterious phenomena, naming his field of study yōkai-gaku, literally 'yōkai-ology' or 'monsterology.' Emblematic of the interplay between academic and popular discourses, Enryō's technical use of the word propelled yokai into common parlance, where it remains today. The conscious use of yōkai by Enryō, and the word's rapid absorption into everyday speech, also reflects the absence of other words flexible enough to encompass the range of phenomena that would come to be considered under its matrix." |

||

|

|

||

|

Yōkai Attack: The Japanese Monster Survival Guide |

|

A wonderful new book - published by Kodansha in 2008 - by Matthew Alt and Hiroko Yoda. It is by far the best book I know of in English that identifies the largest variety of traditional Japanese monsters and gives a scholarly, but fun bit of information about each of them. I would recommend that believers and non-believers alike add this to their library. You can never be too careful, what? |

|

Yōkō |

洋紅 ようこう |

Carmine red: "This was a cheap carmine from Europe used in later prints."

Quote from: Japanese Woodblock Printing, by Rebecca Salter, University of Hawai'i Press, 2001, p. 28.

Yō (洋) means 'Western', 'European' or 'foreign' and kō (紅) means 'crimson'.

When using the kyōgō or keyblock prints for the cutting of the separate blocks used in the final printing Hiroshi Yoshida wrote that he liked to use yōkō to mark particular areas by drawing lines across the area to be printed. |

|

Yomeiri-bon |

嫁入り本 よめいりぼん |

Trousseau books given to a daughter as part of her dowry by a powerful father. Often these were versions, painted in earlier times or printed in later times, The Tale of Genji. "The Genji paintings were deemed suitable for princesses and daughters of powerful families as everyday furnishings, as models for waka composition, and perhaps to initiate male-female relationships upon marriage." Quoted from: Envisioning The Tale of Genji: Media, Gender, and Cultural Production, edited by Haruo Shirane, p. 39. |

|

Yomogi-soba |

蓬蕎麦 よもぎそば |

Soba made with mugwort 1 |

|

Yōraku |

瓔珞 ようらく |

A necklace or diadem, a piece of jewelry decorated with gems; or, "moulded decoration hanging from the edges of a Buddhist canopy". |

|

Yoroi |

鎧

よろい |

Armor

The photo of the armor to the left was found at Pinterest. It is said to represent the armor of "Ii Naomasa (1561-1602), one of the four guardian warlords of Tokugawa Ieyasu... The units Naomasa commanded on the battlefield were notable for being outfitted almost completely in blood-red armour for psychological impact, as such, his unit became known as the "Red Devils" " according to Laura Nickels comment at that site. She says that it was a gift to Hakone Castle from the Ii family. |

|

Yosegi-zukuri |

寄木造

よせぎづくり |

"During the eleventh and twelfth centuries, new religious, economic, and artistic conditions changed image-making, and the traditional reverence of wood was was largely set aside by sculptors working in the capital in workshops serving an aristocratic clientele. Led by the school of Kōsho and Jōchō, these sculptors employed a technique more closely resembling joinery than carving. This joined woodblock technique yosegi zukuri, had evolved gradually in response to increasing production costs and supply demands. Buddhist sculptors had begun experimenting with various procedures to prevent cracking and to lighten the weight of the statue as early as the ninth century. Butsuzō were sometimes cut out from the back or bottom and the resulting hole covered with a separate piece of wood, a technique called uchiguri. Another method called warihagi, involved splitting the wooden log vertically along the grain, hollowing it out, and rejoining it. The statue of Tarōten... in Chōanji is one of the rare shinzō created in this manner. The yosegi zukuri technique offered still further advantages: it enabled sculptors to make large statues using relatively small blocks of wood. Moreover, the interlocking components of the finished work were not as susceptible to cracking due to changing humidity as were those made in the single woodblock method. It also facilitated the organization of a workshop in which each artisan performed an assigned task leaving final assembly and detail work to the master sculptor. Such assembly-line techniques contributed to a mass-produced image of which the thousand statues of Kannon carved for Sanjūsangendō in 1164 are typical."

To the left is an 1880 photograph of row upon row of the statuaries found at Sanjūsangendō found in Kyoto. This photo was posted at commons.wikimedia. |

|

Yōshi |

養子 ようし |

Adoption |

|

Until modern times, i.e., since the Meiji Restoration in 1868, adoption in Japan was unlike anything we know of in Western terms. Practiced for more than 1,300 years it may have begun as a way of leaving a 'family' relative to honor the spirits of the deceased ancestors. At one point it was a vehicle for increasing family wealth among members of the court. Once a young man reached 15, the age of majority, the father could apply for a stipend to be paid in rice or land. If the father had a natural born son who was still a minor he could speed the process up by adopting another, but older young man and make him his son. That young man, in turn, could adopt the younger brother and when he reached 15 apply for a another stipend.

In fact, there were many different types of adoption and many different reasons for them. For example, if a family was fond of a daughter and wanted to keep her in the household they would adopt a son who would then marry her. As a result the daughter might have more power within the family and more of the its wealth would stay in the home. Or, if a family had a lot of children they might allow one of the childless friends to adopt one of theirs. Not only did adoption mean a continuation of a family line, but it also could provide positive political and economic links. There was another consequence of adoption because of a common practice by Edo times: Wealth was only passed on to the eldest son and was not divided among the remaining relatives.

However, it is the issue of adoption when it comes to craftsmen and artists that really matters here. Anyone who has studied ukiyo printmakers and painters will have noticed how many of these were adopted by their teachers/masters or others. Toyokuni II was adopted by Toyokuni I. He was also married to his daughter. Hokusai, Yoshitoshi and Hiroshi Yoshida were all adopted. This custom was also true when it came to ceramicists, sword makers, kabuki actors, etc. Ichikawa Danjūrō II adopted Danjūrō III. Danjūrō IV was said to have been the bastard son of Danjūrō II and had been adopted by another kabuki star. Danjūrō VI was adopted as were Danjūrō VII and Danjūrō IX.

Sources: 1) Mock Joya's Things Japanese; 2) Things Japanese: Being Notes on Various Subjects Connected with Japan by Basil Hall Chamberlain; 3) Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan; 4) New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of Kabuki Jiten by Samuel L. Leiter

|

||

|

|

||

|

Yoshisato |

芳里 よしさと |

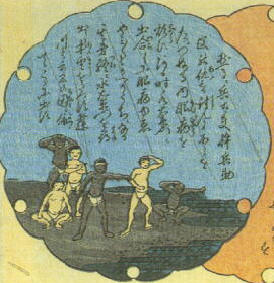

Pupil --- unlisted in Roberts --- of Kuniyoshi who created the inset in one of the prints from the series "Sixty Odd Provinces of Japan - Dramatic Chapters" |

|

Yoshitsune |

源義経 みなもとよしつね |

Minamoto Yoshitsune (1159-1189) was the son of Minamoto no Yoshitomo and Tokiwa Gozen and younger brother of Yoritomo by a different mother. Known as Ushiwakamaru (牛若丸) as a child. He "...had been spared by Taira no Kiyomori after the Heiji war (1159) on condition that he should become a priest and be educated in the temple of Kurama... But the young man escaped and marched against the Taira, whom he destroyed in the Battle of Dan-no-ura... According to a popular tradition he contributed his success to a Tengu, whom he met one day in the shape of a strange man or yamabushi in the Bishop's valley, and who taught him how to handle arms."

Quoted by: "The Tengu", by Dr. M. W. de Visser, published in the Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, 1908, p. 48 |

|

Yoshiwara |

吉原

よしわら |

Famous Edo red light district 1

To the left is a Kunisada print, 'The Yoshiwara at Night' from ca. 1830. We found it at Pinterest. |

|

There is no better example of the Japanese homophonous penchant for ratcheting up the meaning of a word or term than that of the name of the Yoshiwara. In 1617 the Tokugawa shogunate granted a license to Shōji Jin'emon (1576-1644: 庄司甚右衛門) for the establishment of specialized district in Edo. It had taken the government almost 6 years before it approved the original petition submitted by Jin'emon, but when they did they specified the location and the ground rules. "...the place was one vast swamp overrun with weeds and rushes, so Shōji Jin'emon set about clearing the Fukiya-machi, reclaiming and filling in the ground, and building an enclosure thereon. Owing to the number of rushes which had grown thereabout the place was re-named Yoshi-wara (葭原 = Rush-moor) but this was afterwards changed to Yoshi-wara ( 吉原 = Moor of Good luck) in order to give the locality an auspicious name." Filling in and leveling the ground, laying out the streets and building construction took ten years to complete. (Source and quote from: Yoshiwara: The Nightless City, by J. E. De Becker, Frederick Publications, pp. 3-7.) ¶ Along with the license came a set of rules set down by the governor of the district: 1) Brothel-keeping was restricted to this particular location and "...in future no request for the attendance of a courtesan at a place outside the limits of the enclosure shall be complied with."; 2) "No guest shall remain in a brothel for more than twenty-four hours."; 3) "Prostitutes are forbidden to wear clothes with gold and silver embroidery on them; they are to wear ordinary dyed stuffs."; 4) Brothels were told not to build ostentatiously and residents of the districts were to function like the citizens of other districts. For example, Yoshiwara firemen were subject to the same rules of firemen elsewhere in the city; 5) Each visitor to a brothel is to be questioned and scrutinized. "...in case any suspicious individual appears..." the governors office must be notified. There was to be no exceptions whether the visitor is a "gentleman or a commoner..."; "The above instructions are to be strictly observed." (Ibid., pp. 5-6)

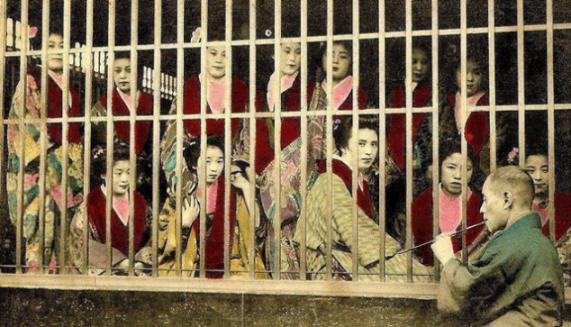

Above is an early photograph of prostitutes in the Yoshiwara on display behind the harimise, i.e., wooden lattice screen.

The original or 'Old Yoshiwara' was ordered to move to a new location in 1657 after a major fire and hence was renamed the 'Shin' or 'New Yoshiwara'. This is the pleasure quarter we know so well from the prints of the ukiyo. [Note that large urban fires have not been rare in historical Japan. However, before the modern age this was a threat common to all large cities: London burned down in 1666.] ¶ The Yoshiwara should not be thought of strictly as a place where men went for sex. It had a remarkably subtle and profound effect on Japanese culture. "It would be a mistake to think of the Yoshiwara as a simple collection of brothels; rather, it was a highly stratified and complex world in itself that provided the means for a very sophisticated level of entertainment. New genres of music, art and literature developed around it... ¶ Many scholars have pointed out that... quarters like the Yoshiwara provided the one institutionalized escape from social repression and control. That is the social rank of warrior, farmer, artisan and merchant (shi-nō-kō-shō), which dictated how a person lived, married, worked, and dressed, were of secondary importance to the main key for enjoying oneself in Yoshiwara - namely money." (Quoted from: 'Yoshiwara', Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 8, pp. 349-50. This entry was written by Liza Crihfield.)

There is an account called The Yoshiwara From Within ostensibly written by a Japanese native in the 19th century. It has been reprinted at least once and is filled with fascinating details. In one editorial moment the author compares the overall nature of prostitutes in the West to those of Japan: "...though it is probably true that fallen women of Japan are, as a class, less vicious than their representatives in Western lands - less drunken, less foul-mouthed. On the other hand, a Japanese proverb says that a truthful courtesan is as great a miracle as a square egg." ¶ In 1874 the government ordered weekly medical inspections in imitation of European practices. To fund this and other administrative practices plus policing the red light districts and their inhabitants were heavily taxed. ¶ The author notes that in an odd book published in Japanese, English and Chinese, Pictorial Description of the Famous Places in Tokyo, that in a list of the most prominent citizens only lists "...all of them without exception popular harlots." |

||

|

|

||

|

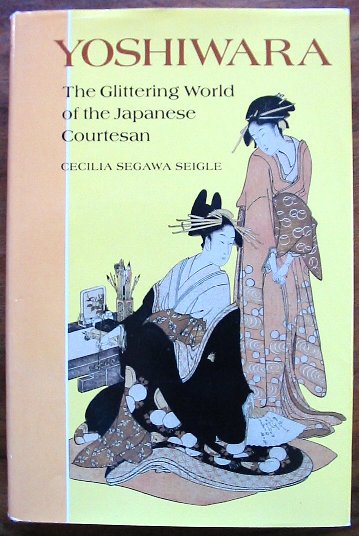

Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan |

|

|

|

Yotaka |

夜鷹

よたか |

A low-class prostitute, a common streetwalker. Also the name of a type of bird, the nighthawk, nightjar or goatsucker.

The image of a yotaka to the left is by Hiroshige and is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The image shown above is a surimono by Sadakage. |

|

"Note on "Jigoku" or Illicit

prostitutes. |

||

|

Yotsude-ami |

四つ手網

よつであみ |

Four-cornered scoop fishing net 1 |

|

Yotsume |

四つ目

よつめ |

A mon or crest which includes variations of four boxes grouped together. However, unlike most other mons I haven't a clue about it significance other than decorative and distinctive.

Even inexplicable crests are ready tools for scholars. Timothy Clark noted this in describing the background to a triptych by Utamaro: "The crest of four squares...inside a circle on the steaming boxes [seirō - 蒸籠 ] is that of the cake shop of Takamura Ise (Yorozuya Ihei) located in Edo-chō 2-chōme in Yoshiwara. The type of cakes known as monaka no tsuki [最中の月] from this store were famous."

Quote from: The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, text volume, p. 153 |

|

Yozakura |

夜桜 よざくら |

Viewing cherry blossoms at night.

Yozakura at Senshu Park |

|

Yüan (dynasty) |

元(朝) |

Name of the 13th c. Mongol rulers of China 1 |

|

Yūgao |

夕顔

ゆうがお |

Bottle gourd or moonflower - also the name of one of the chapters in the Tale of Genji.

To the left is a Yoshitoshi print which we found at Pinterest. Above is a bottle gourd from botanic.jp. |

|

Yuiwata |

結綿

ゆいわた

|

A bundle of silk floss: This was the personal crest or mon used by several actors performing under the name Segawa Kikunojō.

The detail from a Bunchō print to the left (bottom) shows the crest prominently displayed on the robe of Segawa Kikunojō II from ca. 1770. This detail is shown courtesy of Kabuki21, the best site of its kind on the Internet. I urge that you visit it - long and often.

This motif can also be referred to as simply wata (綿).

|

|

Yukata |

浴衣

ゆかた |

Literally translated as a bath garment.

A light summer garment made of cotton often used for casual attire or as a bathrobe. Most frequently decorated with designs dyed in indigo blues. "Yukata came from yukatabira (bathing katabira) to distinguish it from katabira or linen dress for ordinary summer wear. Originally yukatabira, as its name indicates, was worn after taking a bath, for drying up the body. Thus it took the role of bath towels at first. They used to put on one yukata upon coming out of the bath tub, and changed it for another until the body was thoroughly dried. Thus it was called minugui or body wiper."

Source: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 53.

Yukatabira (浴衣びら or an alternative 湯帷子); katabira (帷子); minugui (?).

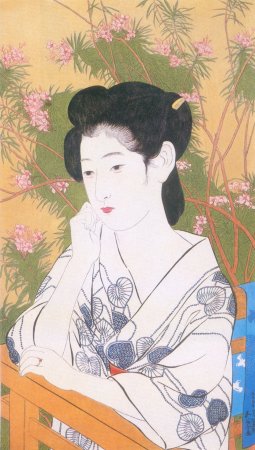

The image to the left is by Goyo. |

|

"Although for the older generation the yukata is still considered to be little more than a bathrobe, for the younger generation the yukata is an “one-piece” easy-to-wear summer kimono for going to festivals, fireworks, and parties with friends. Nevertheless, as can be seen in Ukiyo-e prints, even in the Edo period the yukata was worn not a only as bath-wear or sleepwear, but also as fashionable summer dress, the latter made of more elaborate patterns and dye techniques—to the extent that the fashionable yukata were often designated by their dye techniques (momen-shibori, momen-komon, or chūgata), rather than being simply dubbed a yukata. When exactly the yukata lost its status of fashionable summer garment is unclear, but is likely related to various factors such as the end of the sumptuary laws forbidding commoners to wear silk, coupled with the kimono dying out as everyday wear, and the yukata then becoming only regularly worn for bed or bath." This is part of the abstract to a paper by Karen Mack entitled: "The History of Yukata Fashion: Part I Edo Period" (浴衣の着こなし史 1-江戸時代).

This yakata was found at Pinterest, but it originally comes from our friends at Srithreads.com.

"The colorful summer robe of today, called yukata, was once a simple asa-hemp robe worn for bathing. Yukata and the word itself derives from the yukatabira [湯帷子]. The “yu” in yukatabira means hot-water and “katabira” means a thin plain unlined robe. In the Heian period (794-1185), the katabira was made of asa-hemp or raw-silk and worn next to the skin as the innermost layer of clothing, basically underwear. Baths were not taken nude, rather the katabira was worn while in the sauna-style bath..." (Ibid., p. 101)

Mack continues: "In the Edo period (1600-1868), katabira came to refer to unlined summer robes made of asa-hemp or raw silk, in distinction to unlined robes, called hitoe, made of silk or cotton, and unlined informal robes called yukata (Nakae 1987: 121,411-412). During this period the yukata likewise developed a distinct form and function from the original yukatabira undergarment, to the extent that it is even arguable how much the two are actually related. The literal meaning of yukata is “bathing robe,” but already in the Edo period the yukata developed beyond a simple bathrobe to become a fashionable informal garment of summer." (Ibid., p. 102) |

||

|

|

||

|

Yuki |

雪 ゆき |

Yuki is the Japanese word for snow. |

|

There is an interesting passage in Snow Country Tales: Life in the Other Japan by Suzuki Bokushi (translated by Jeffrey Hunter with Rose Lesser, published by Weatherhill, 1986). Bokushi (1770-1842: 鈴木牧之) lived in Echigo, modern Niigata Prefecture, "snow country". He wrote a wonderful comparison of his native region which was buried in snow every winter with that of Edo, modern day Tokyo. In the section entitled "The First Snow" he wrote: "The people of friendlier climates take pleasure in the snow. In Edo, where some years it doesn't snow at all, the first snow is regarded as especially delightful. People set out in little boats, accompanied by geisha, to watch the snow; important guests are invited to tea ceremonies held in the snow; the brothels use the snow as an excuse to encourage their patrons to spend the night; and the restaurants and bars regard snow as an omen of many customers. It is difficult to count the many entertainments in the snow that have been devised. But the great degree to which the snow is celebrated in Edo is a mark of that city's great plenty. The people of the snow country can't help but be envious when they see and hear these things. The difference between the first snow in Edo and our first snow is the difference between pleasure and pain, clouds and mud." (p. 10)

We were very struck by the passage quoted above. But it wasn't just us who liked it. John W. Dower did too. He quoted it in his The Elements of Japanese Design, but he didn't cite his source. Not only that, but it was quite by accident and fortuitous that we found this out at the same time we were reading Snow Country Tales: Life in the Other Japan. |

||

|

|

||

|

Yuki-Daruma |

雪達磨

ゆきだるま |

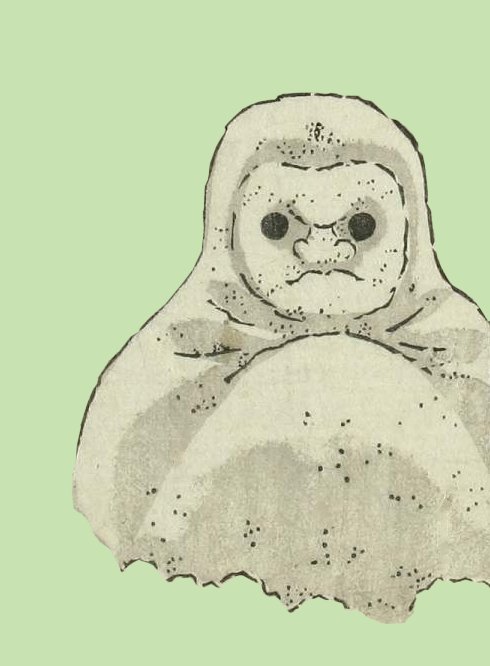

Typical and traditional Japanese snowman. In fact, Jim Breen's web site gives the kanji translation as simply 'snowman'. Lafcadio Hearn tells us that "The rules for making a Yuki-Daruma are ancient and simple." First a snowball 3 to 4' in diameter. Place a smaller one of about 2' on top of that. Pack in snow around the base of each ball, add coal for the eyes, nose, etc., and voila! Later, unlike the image by Kunisada to the left, hollow out an area for the navel "...and still a lighted candle inside. The warmth of the candle gradually enlarges the opening..."

Source and quotes: The Writings of Lafcadio Hearn, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1922, 381. (There is also a 1901 edition.)

Make sure you see our entry on Daruma too for more information.

The Old Taoist: The Life, Art and Poetry of Kodôjin (1865-1944) by Stephen Addiss, Jonathan Chaves and J. Thomas Rimer (Columbia University Press, 2001, 45) quotes a haiku on a painting of a snow daruma. It notes that the word jakemetsu (寂滅) which is used here can refer to 'nirvana' or 'fading away'. This, of course, is the related to the innevitble nature of a melting snowman.

Lafcadio Hearn in his Buddhism - Gleanings in Buddha-Fields; Studies of Hand and Soul in the Far East: Studies of Hand and Soul in the Far East (reprinted by Read Books, 2006, p. 169 - originally published in 1927) quotes a Japanese folk song: "Shadow and shape alike melt and flow back to nothing / He who knows this truth is the Daruma of snow."

Note that there are also references to a snow Buddhas or yukibotoke (雪仏). One poem refers to the melting of a snow Daruma into a mud Buddha. |

|

As the ancien regime was coming to an end there was a great swell of anti-Buddhist feeling: "Emperor Kōmei (...r. 1847-1866) was the last Japanese emperor to be buried with Buddhist funerary rites... [This] proved to be the last public display of Buddhism for several years. By Kōmei's third memorial service (in 1868), which took place three months after the Meiji Emperor assumed the throne, Imperial rites and ceremonies were well on their way to becoming completely divested of any Buddhist character. The third memorial service itself was performed in accordance with a newly devised Shinto ceremony."

Quoted from: Of Heretics and Martyrs in Meiji Japan: Buddhism and Its Persecution, by James Edward Ketelaar, Princeton University Press, 1990, p. 44.

In the fifth month of 1872 (Meiji 5) Order number 133 was issued by the Ministry of State. The intention was to diminish the influence of Buddhism within the culture and the state and to segregate what remained. "The policy carried out in the early years of the Meiji era and commonly known as the 'separation of Shinto and Buddhism' (shimbutsu bunri [神仏分離]) was expanded by order number 133 to include the separation of Buddhism from the state itself. There is, in other words - in addition to the particular factional, political motivations of Nativist and Confucian ideologues to eliminate Buddhism as a political force - the beginnings of the notion, which would gain greater currency in the mid-Meiji era, that persons or institutions predominantly concerned with 'religion' were generally ineffective operatives within the political arena. (Ibid., p. 6)

"The renewed importance of the Shintō priesthood and the insistence on insistence on separating Shintō from Buddhism were made more explcit four days later when Shintō priests who served concomitantly as Buddhist priests were ordered to yield their Buddhist ranks and positions, give up their Buddhist robes, and let their hair grow out. [¶] For more than a thousand years, most Japanese had believed simultaneously in both Shintō and Buddhism despite the inherent contradictions between the two religions."

Quoted from: Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852-1912, by Donald Keene, Columbia University Press, 2002, p. 137.

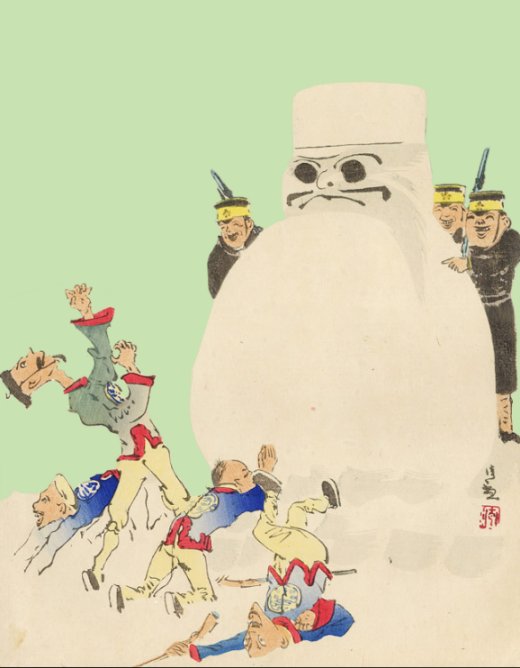

That information above is what makes this image by Kiyochika (ca. 1895) that much more interesting. From a series entitled "100 Victories, 100 Laughs" in which the Chinese soldiers are constantly mocked for their superstitions and ineptitude. Here the Chinese are apoplectic before the militarized yuki-Daruma which instead of symbolizing a friendly and benign Buddhist deity has been transformed into a stern and fearsome Japanese infantryman complete with soldier's cap. Perhaps no Japanese image was out of line when it came to poking fun at the enemy. (For another example by Kiyochika see our entry on tombo or dragonflies.) |

||

|

|

||

|

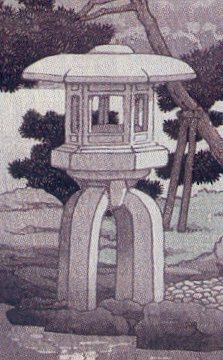

Yukimi dōrō |

雪見灯籠

ゆきみ.どうろう |

Literally a snow viewing lantern. It is said that the 'snow viewing' part has more to do with the beauty created by the newly fallen snow as it piles up on top than it does for the way the lantern illuminates its surroundings.

The yukimi dōrō is only one type of stone lantern or ishi dōrō (石灯籠). Mock Joya states that there are 200 varieties of stone lanterns.

Despite what you might read at some sources that claim to be the definitive answer this type of stone lantern can have either three or four stone legs.

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Hasui from 1938. 1 |

|

Yukiwa |

雪輪

ゆきわ

|

The snow circle or ring motif: "Although the snowflake was not one of the dominant motifs among Japanese crests, the stylized 'snow ring' enclosure... became a popular and elegant convention. Apart from its obvious beauty, snow was also regarded as an auspicious sign of a bountiful year to come - possibly because winter snows meant spring rivers and fertilization of the soil. In early Japanese court society, the year's first snowfall became the occasion both for festive snow-viewing parties and for official meeting to decide appointments for the coming year." (Quote from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 42)

This motif also appears as a decorative pattern or occasionally as a title cartouche.

The image to the left below is a similarly shaped cartouche from an inset on a Kuniyoshi Tokaido road series. The image above is the title cartouche from a Kunisada II. |

|

Yumi |

弓 ゆみ

|

Bow: "Uniquely Japanese asymmetrical bow, about 2 m long, made of glued bamboo blades held together by rings that are also made of bamboo. This type of bow was created for horsemen, and the handle was about one-third of the way up from the base. Considered sacred, it is said to be able to ward off evil influences when its silk cord is vibrated... It is still used in traditional Japanese archery (kyūdō) and for concentration exercises in Zen practice." Quoted from: Japan Encyclopedia by Louis Frédéric, p. 1067. |

|

Yumiya |

弓矢

ゆみや

|

Bow and arrow.

The image on the left in the center is a detail from a Kuniyoshi Suikoden print. Above is a close-up showing the descent of a flying goose which has just been struck through. On the bottom is an enlarged detail of the quiver with arrows.

This figure represents Shōrikō Kaei. "The manner in which Kaei holds his bow is unusual: the string of the bow is depicted on the left side of his left arm which would make it extremely difficult to shoot an arrow with the right hand." (Quote from: Of Brigands and Bravery: Kuniyoshi's Heroes of the Suikoden, by Inge Klompmakers, Hotei, Leiden, 1998, p. 86)

Shortly after I posted

the information shown immediately above I received an e-mail from a fellow I

know to be an adept at or expert in quite a few areas including ukiyo-e,

Kuniyoshi, etc. What I didn't know is that he is also extremely

knowledgeable about archery. He said that

Klompmakers statement is incorrect: "Anybody who has used a reasonably

powerful bow knows that after the release of the arrow the bow tends to whip

round into the position shown. Most archers will wear a leather wristguard

on their arm because the impact can sting

Then yesterday, June 15th, 2006, I received another e-mail from an expert in Portugal:

"In Japanese

archery, when releasing the string... the bow rotates almost 360 degrees, so

the string travels from the right side of the bow arm until almost or even

touching the arm on the left side. the bow performs an almost perfect circle

around itself. This is called 'Yugaeri' [弓返り or ゆがえり]. A perfect shot

has a perfect yugaeri, so in the image, the string being on the left

side of the bow arm, just means that it was a flawless shot.

Now this is dynamite information and I want to thank Carlos Freitas, President of the Portuguese National Archery Federation for it.

In defense of Klompmakers it seems to me that ignorance of the fine points of Japanese archery would make this kind of mistake reasonable.

The Kuniyoshi image to the left was sent to us by our great contributor E. Thanks E! |

|

Yūrei |

幽霊 ゆうれい |

One possible translation of the characters could be 'faint' and 'spirit' or 'soul.'

Hiroko Yoda and Matt Alt in their Yokai Attack define yūrei as "A spirit that has, for whatever reason, Not entered the after-life. Essentially, a ghost."

Mary Picone wrote in 1991: "Ce n'est qu'avant la dernière guerre que les ethnographes japonais ont essayé de distinguer, parmi les manifestation surnaturelles autochtones, les revenants humains (yūrei, 'esprits obscurs' ou indistincts) et les apparitions (yōkai)." |

|

Zabuton |

座蒲団

ざぶとん |

A floor cushion used generally for sitting or kneeling. |

|

Zakoba |

雑魚場

ざこば |

Zakoba was an Edo period fish market near Osaka.