|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

||

| Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

Kakure-mino thru Kappazuri |

|

|

The molecular model on Lonsdaleite is being used as a marker for new additions from January 1 to May 31, 2021. |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Kakure-mino, Kakurezatō, Kakushibaba, Kama,

Kami, Kamigata yakusha-e shūsei, Kamikakushi, Kamishimo, Kamiyui, Kammuri, Kamuro, Kanagaki Robun, Kanban, Kanbun, Kane, Kan-ei, Kane no naru ki, Kani, Kankan, Cancan, Kanpyō, Kannushi, Kanreki, Kansubon, Kanteiryu, Kantō daishinsai, Kantō hasshū, Kanzashi, Kanzemizu, Kantō/Kansai, Kaomise, Kappa, Kappazuri

隠れ蓑, 隠れ座頭, (かくし)婆, 鎌,

神, 上方役者絵集成, 神隠し, 髪結, 冠, 禿, 假名垣魯文, 看板, 漢文, 鉦, 寛永, 金のなる木, 蟹, 看看, 乾瓢, 神主, 還暦, 巻子本, 勘亭流, 関東大震災, 関東八州, 関東/関西簪, 観世水, 顔見世, 河童, 唐傘, 空摺, 合羽摺 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Kakure-mino |

隠れ蓑 かくれみの |

Oh, to be a fly on the wall. Who hasn't wanted to be that. Well, this goes one better: A cape of invisibility. Whereas this may sound like a modern anime concept I know that it goes back as far as 1821 if not earlier because it is represented in a surimono by Hokusai from that time. Note that now I know it goes back to much earlier times. See the new information and opinions posted below. |

|

In The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon (translated by Ivan Morris, Penguin Books, 1979, p. 131) the author was trying to sneak a peek at the visiting sister of the Empress. She was hidden away until it "The screen behind which I had been peeping was now pushed aside and I felt exactly like a demon who has been robbed of his straw coat." In footnote 281 Morris notes: "Demons had straw coats that made them invisible." I mention this because the issue of invisibility is universal and not unique to the Japanese. During the Bon Festival the spirits of the dead visit their relatives. Among the Jews a cup of wine is set out for the prophet Elijah at Passover. The door is opened to make his access easier, but he never reveals himself although it is believed that he does observe the ceremony. I could give an example for almost every cultural group, but here we will concentrate on the Japanese. ¶ C. W. Nicholl wrote about 'sacred groves' in which he talks about a Japanese hunter: "Someone asked: 'How do you know there are deities in this place? Can you see them?' I thought it a silly question, but the hunter replied with a smile: 'The deities are invisible, but I know they are here even though I can't see them.' " (Quoted from: Shinto in History: Ways of the Kami, by John Breen and Mark Teeuwen, University of Hawaii Press, 2000, p. 32)

"The precise origins of the raincoat of invisibility are not known, but it is likely that the cape was first associated with Chinese Taoism. Taoist adepts strove to develop the power of being invisible, believing that this would help them move between heaven and earth. In Japan, the raincoat of invisibility is one of the Myriad Treasures of the Seven Gods of Good Luck..." (Quoted from: Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design, by Merrily Baird, Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 2001, p. 239)

In The Taoist Experience: An Anthology Livia Kohn says: "They can become visible and invisible at will and travel thousands of miles in an instant." (p. 280)

In The Yanagita Kunio Guide to the Japanese Folk Tale section 156 (pp. 158-60) deals with "The Invisible Straw Cloak and Hat". Yanagita Kunio (柳田國男) lists 15 variatins. In most of these tales a human wins or trades a tengu for the cloak.

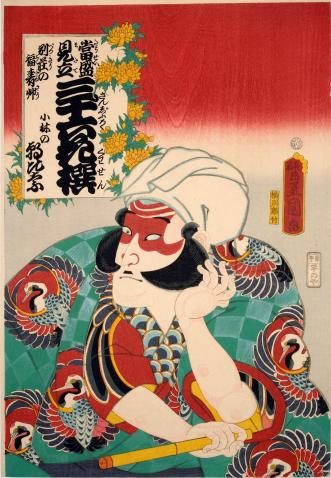

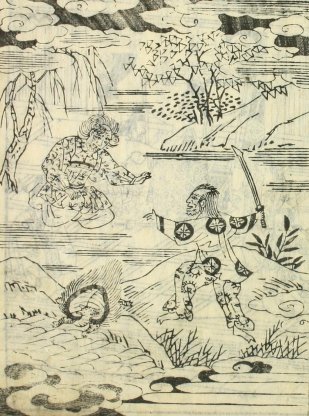

Above is a detail of two tengu by Toyokuni I. There is no invisibility cloak in this image - or is there? - but the image is just too good to pass up.

Donald Keene in his massive Seeds in the Heart: Japanese Literature from Earliest Times to the Late Sixteenth Century (p. 803) refers to a now lost tale from the 11th century, Kakuremino (The Invisible-Making Cape), and its probably influence on the extant version of Parting at Dawn. In the first section of the latter the main character is able to make himself (actually herself disguised as a male) invisible and thereby is able to visit the bed chambers of quite a few people learning some of their most intimate secrets.

In the Pillow Book of Sei Shōnangon as translated by Ivan Morris the author has been ordered by the Empress to spy on other members of the court. However, when a screen is moved and Shōnangon is discovered she compares herself to feeling "...exactly like a demon who has been robbed of his straw coat.

The demons of Oni-ga-shima (鬼が島), Devil's Island, make it a habit to wear both kakure-mino and kakure-gasa, invisibility cloaks and hats.

There is a Korean folk tale which has its counterpart to the Japanese kakure-mino. A peasant went to a distant mountain to cut wood. A sudden rainstorm forces him to seek shelter in an abandoned house. By the time the rain had stopped it was night. After a while the peasant heard the noise of an approaching group so he hid in the attic. The group turned out to be a bunch of goblins who cavorted through the night. After they left the peasant went back down and found that the goblin had left a vest behind. He put it on and went home to show it to his wife. However, what he didn't realize is that he had become invisible and she wouldn't be able to see him. From this he hatched a scheme to wear the vest and to go into shops to rob them. This he did for some time until he wore it into a crowded marketplace. The lit pipe of one of the merchants burned a hole in the vest. The peasant asked his wife to patch it. She did, but with a piece of red cloth. In time the merchants realized that whenever they would see a red patch floating along they would be robbed. This is how the caught the peasant thief. They beat him to death. (Source: Myths and Legends from Korea: An Annotated Compendium of Ancient and Modern Materials by James H. Grayson, p. 330)

There is a curious thing about the term kakure-mino: It is also the name of a plant using the same kanji characters - 隠蓑. Why? Does anyone out there know? There are tons of plants named after famous and not-so-famous people and other things, but this seems an odd choice here. Is there any connection between this plant and the cloak of invisibility? The Dendropanax trifidus is a small, evergreen tree of the Ginseng family. The two images posted below were supplied by Shu Suehiro at his wonderful site http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. (We do know that the name goes back at least as far as the early 19th century.)

In Serene Gardens: Creating Japanese Design and Detail in the Western Garden by Yoko Kawaguchi (p. 124) it says: "...moist shade; very slow growing; dislikes being pruned; resents root disturbance; suitable for north-facing gardens; used in shrines and tea gardens." They also point out that it grows to 32'.

The resin of the Dendropanax trifidus was "...used as a readily available photopolymerizable protective varnish for armor and metalwork in Japan." (Quote from: Plant Resins: Chemistry, Evolution, Ecology, and Ethnobotany by Jean H. Langenheim, 2003, p. 410) Later the same page our source notes that "Other species of Dendropanax produced resins for similar use in Korea and China, known during the T'ang dynasty as ushitsu (golden varnish)." [Note: These quotes also appear verbatim in an earlier publication of the Organic Chemistry of Museum Objects by Mills and White.]

Perhaps this tree carried the name of the cloak of invisibility because when smaller it is densely packed with leaves which form an evergreen privacy screen as described in Garden Plants of Japan by Ran Levy-Yamamori and Gerrard Taaffe (p. 96).

There are numerous references to the use of kakure-mino, the cloak of invisibility, as a 20th century euphemism meaning bureaucratic obfuscation.

There are quite a few books on dermatology which mention the Dendropanax. One of them, Fisher's Contact Dermatitis by Rietschel and Fowler (p. 430), says: "In Japan, the plant commonly known as kakuremino (because it resembles a Japanese straw coat) is Dendropanax trifidus Makino." [Note: We have looked at numerous images and so far have found none that look like the traditional straw raincoat.]

In the Kanji Handbook by Vee David (p. 840) it defines kakuremino, 隠れ蓑, as 'cover, shield'. [By parsing the kanji we have 隠 (conceal) plus 蓑 (straw raincoat).] |

||

|

|

||

|

Kakurezatō |

隠れ座頭 かくれざとう |

Goblin: Carmen Blacker in her Supernatural Abductions in Japanese Folklore (published by Nanzan University, Asian Folklore Studies, Vol. 26, No. 2, 1967, p. 115) says that these are among the noted figures which abduct young children and adults or women. So far I have found little to no information about this creature. When or if I do you will be among the first to be told. Not only that but Blacker's reference is in a short footnote. (This information as conveyed by us may be incorrect. At some point we shall try to check this.) |

|

Henri Joly in his Legend in Japanese Art says that Kakure zato was "The blind old man entrusted with the conveyance bad people to Hades." However, the kanji he used was 隠れ坐頭 which is slightly different.

The kanji for kakurezatō, 隠座頭, is also the name for the death-watch beetle. That in turn is also referred to as the tea-making insect or cha-tate mushi (茶立虫) because of the sound it makes.

There is a near homonym for kakurezatō meaning 'hidden villages' which is a euphemism for an unlicensed red-light district. The first kanji character, 隠, is the same here. The second character is different - 里, but this one does not have a long 'o'.

"The word in Japanese used to denote a village hidden or lost in the mountains is kakurezato, and the Heike villages are often designated by this term. But kakurezato has another meaning, very different from the poor and primitive hamlet described by Suzuki. This is a hidden paradise, an 'other world' altogether, a miraculous realm of treasure and limitless wealth, a source of magical prosperity. This other world is situated underground, and is to be reached by means of certain entrances, which are usually watery in nature. A pool or a lake or a well carries the legend that once, long ago, it was a gate into another world of wealth and bliss. Dry entrances are also to be found, usually in old tombs, mounds and caves." Quoted from: The Exiled Warrior and the Hidden Village by Carmen Blacker. |

||

|

|

||

|

Kakushibaba |

(かくし)婆 かくしばば |

Hags that abduct children, women or young adults. (See the kakurzatō entry above.) Again, there is almost nothing written in English about this term. In fact, there is almost nothing in Japanese either. |

|

Kama |

鎌

かま |

A sickle or scythe - Below is an image from the Lyon Collection showing Yoemon about to slay his daughter, Kasane. Click on the image to go to the page devoted to this print.

This is a motif which occasionally appears on fabrics. We shall add an image once we have found one we can use. Stay tuned.

The image to the left was posted at Flickr by Shintaro Oda. |

|

|

鎌髭

かまひげ

|

Sickle-shaped moustache/sideburns (often worn by servants in the Edo period); a motif often part of the kabuki figure Asahina's makeup. Literally it means 'scythe' and 'beard or moustache'.

One of the 18 plays performed by the Ichikawa group is called 'Kamihige'. The origins are unclear, but may have been produced in one form or another as early as 1719 when a very young Ichikawa Danjūrō IV pretended to shave a beard with a large scythe. As the play developed over time, there is a scene in the second act in which a character named Yoshikada, but in actuality is Kagekiyo, stops at a smithy's shop and asks for a shave. The smithy is actually not who he seems to be but is one of Kagekiyo's archenemies. He agrees to give him a shave just so he will have the opportunity of cutting Kagekiyo's throat with a scythe. However, Kagekiyo's skin is magically strong and will not give under the strength of the blade. The two antagonists then glower fiercely at each other. Later Kagekiyo uses magic to transform himself into seven different people.

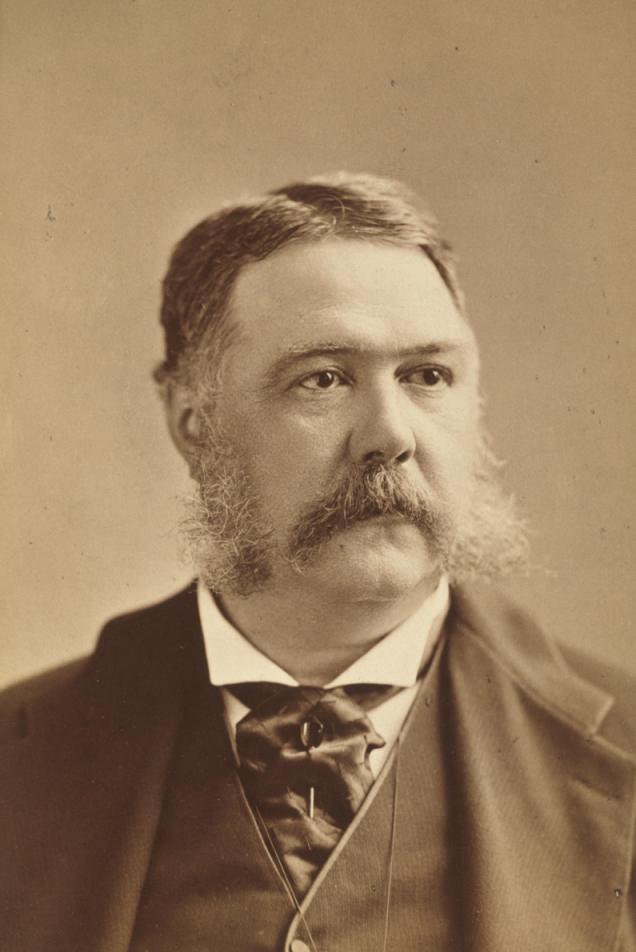

The image above to the left is a detail from an 1823 surimono of Asahina by Gakutei. Below is an 1862 Kunisada print of Asahina in the British Museum. Below is a photograph of President Chester Alan Arthur (1829-86) with mutton chop sideburns.

|

|

Kamakurajidai |

鎌倉時代 かまくらじだい |

The Kamakura period 1185-1333 |

|

Kambun |

寛文

かんぶん

|

The reign period from 1661-1673. "By now Edo had recovered from the Meireki Conflagration (1657) and the decade of the 1660's saw the rapid development of urban culture - Kabuki, jōruri, genre art, books, printing - forming a preparation-ground for the more famous Genroku Period. Kambun witnessed the first consolidation of the ukiyo-e school, under Moronobu's anonymous mentor the 'Kambun Master' - many of whose printed works were in the shunga genre, the favored subject for limited editions at the time. Kakemono paintings of girls also became a standardized genre of ukiyo-e, to be later known as 'Kambun bijin'." Quoted from: "Historical Eras in Ukiyo-e" by Richard Lane in Ukiyo-e Studies and Pleasures, Society for Japanese Arts and Crafts, the Hague, 1978, p. 28.

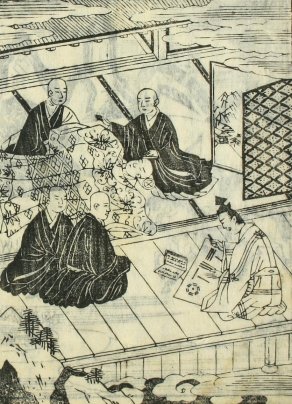

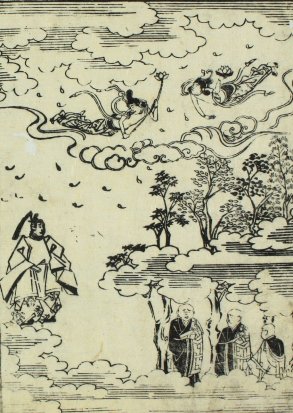

Above is a book illustration to the life of Prince Shōtoku dating from 1666.

The two book illustrations to the left come from the Soga monogatari from 1663. |

|

Kame |

亀

かめ |

Tortoise or turtle: Donald Keene noted that "In certain Buddhist texts the rarity of meeting a Buddha is compared to the difficulty of a blind sea-turtle's chance of bumping into a log to float on. The turtle emerges to the surface only once a century and tries to clutch the log, but it has a hole and eludes his grasp; this was a simile for the difficulty of obtaining good fortune."

Below is a photo of a sculpture at Oyashirazu posted at commons.wikimedia by Kropsoq

On the left is a manjū turtle posted at commoms.wikimedia by kisocci. A manjū (饅頭) is a type of bun. Traditionally stuffed with a bean paste. Now it can be with almost anything edible. |

|

Kami |

神 かみ |

Brian Bocking in A Popular Dictionary of Shinto begins his entry on kami with "A term best left untranslated. In Japanese it usually qualifies a name or object rather than standing alone, indicating that the object or entity has kami-quality. Kami may refer to the divine, sacred, spiritual and numinous quality or energy of places and things, deities of imperial and local mythology, spirits of nature and place, divinised heroes, ancestors, rulers and statesmen. Virtually any object, place or creature may embody or possess the quality or characteristic of kami, but it may be helpful to think of kami as first and foremost a quality of a physical place, usually a shrine..." (84) Later Bocking notes: "Although Shintō purists like to reserve the term kami for Shintō (rather than Buddhist) use, most ordinary Japanese make no clear conceptual distinction between kami and Buddhist divinities, though practices surrounding kami and Buddhas may vary according to custom. This accommodating attitude is a legacy of the thorough integration of the notion of kami into the Buddhist world-view which predominated in Japanese religion before the reforms of the Meiji period and has been to some extent revived since 1945, often through the new religions. This is despite the 'separation of kami and Buddhas' (shinbutsu bunri) of 1868, when deities enshrined both as Buddhist divinities and as kami of a certain location... had to be re-labelled as either Buddh/bosatsu or kami. In understanding Japanese religion, to think of kami as constituting a separate category of 'Shinto' divine beings leads only to confusion. The 'shin' of 'Shintō' is written with the same Chinese character as kami." (p. 85) |

|

W. Michael Kelsey in the introduction to his article "The Raging Deity in Japanese Mythology" published in Asian Folklore Studies (Vol. 40, No. 2, 1981, p. 213) gets right to the point: "The Japanese kami, an enigmatic creature if ever there was one, is not always a benevolent force living in harmony with human beings. Indeed, Japanese mythology is filled with accounts of deities who kill travelers through mountain passes; who rape, kill and eat women; or who bring epidemics on the people when dissatisfied with the upkeep of their shrines.2 Deities engaging in acts of violence were termed araburu kami 荒ぶ,る神 or raging deities, and their pacification posed a real problem for the ancient Japanese. As we shall see in the following pages, these deities often assumed the form of a reptile when engaged in their anti-social behavior, and although they cannot be called inherently evil, they were nonetheless a threat to human beings which needed to be dealt with."

Kelsey notes that there are many examples of the duel nature of kami: They can be both malevolent and beneficent at the same time. "In Mie Prefecture, for example, at the Shinto shrine Takihara no Miya, there are two buildings standing side by side. Both of these are dedicated to Amaterasu no Omikami, the Sun Goddess, but one is for her peaceful nature (nigimitama 和御魂) and the other for her violent nature (aramitama 荒御魂). These two aspects of her personality exist simultaneously, and both must be worshiped." (Ibid. p. 227) The author goes on to ask why kami would frequently take the shape of a reptile when doing evil. His response: The form doesn't really matter because "The answer very often seems to be that it has allowed its energy (and a kami is nothing if not energy) to run unchecked..." in whatever form it chooses to take. (p. 228)

More information is provided by Kelsey in his first footnote to this article: "The arguments concerning the origin and ultimate meaning of the word kami are complex and conflicting. In this paper I will translate it as 'deity,' with the following observations: a kami has no absolute power and it was not the only supernatural being recognized and worshiped by the ancient Japanese. A kami is "superior" to human beings but not necessarily "better" than them. There are male, female and bisexual kami, and I have settled on the unspecified pronoun 'it' except when the sex of the kami is made clear." (p. 233)

"Motoori Norinaga, a great eighteenth century scholar of the Shinto Revival, remarked that anything which was beyond the ordinary, other, powerful, terrible was called kami. Thus the emperor, dragons, the echo, foxes, peaches, mountains and sea, all these were called kami because they were mysterious, full of strangeness and power. Kami may thus be descried in certain people, in certain trees and stones, mountains and islands; in the excellence which overshadows the practice of certain crafts, in the continuity and protection which attends a family stemming from a remembered ancestor. In all of these things there shows through, as though through a thin place, an incomprehensible otherness which betokens power" (Quote from: The Catalpa Bow: A Study of Shamanistic Practices in Japan by Carmen Blacker, p. 34) ¶ "Elusive, shadowy, largely formless though these beings may be, in their disposition and status they are many and variable. Some are great kami, with names recorded in mythical chronicles, who exercise power over a wide area of man's life. Sickness, fire, seasonal rain and marital happiness may all lie in their gift. Others of humbler status confine themselves to narrower spheres, specialising in easy childbirth, good fishing catches or cures for diseases below the navel. Some are remote, static, slow to take offence. Others impinge closely on our world and are quick to react to the treatment they receive here." Kami can represent a region, a village, a family or an individual, but all share a single trait which enables a shaman to communicate with them. (Ibid., p. 35) |

||

|

|

||

|

Kamigata yakusha-e shūsei |

上方役者絵集成

かみがたやくしゃえしゅうせい |

A five volume set of which I have only the first four. A great reference source for identifying actors, plays, dates, theaters and publishers of many Osaka actor prints. Mostly in Japanese, but with some information in English at the end of each volume. The first two were compiled by Susumu Matsudaira. The third volume was by Matsudaira and Hiroko Kitagawa. The last two are by the latter.

Recently I borrowed volume 5 so I can show it to you here. This volume is dedicated to the art of Utagawa Yoshitaki. |

|

Kamikakushi (or kamigakushi) |

神隠し かみかくし or かみがくし |

"In Japan a rather similar belief in supernatural kidnapping survived in many districts until modern times. A boy or young man who unaccountably disappeared from his home was assumed to be not lost but stolen, to be the victim of kamigakushi or abduction by a god. If all reasonable search for him proved fruitless it was concluded that some god or goblin had carried him off to its own realm. In such emergencies the whole village considered it a duty to turn out at sunset with lanterns, and to march round in procession, banging loudly on bells and drums and shouting, 'Bring him back, bring him back !' "

Quoted from: "Supernatural Abductions in Japanese Folklore", by Carmen Blacker, published by Nanzan University, Asian Folklore Studies, Vol. 26, No. 2, 1967, p. 111.

The abductee frequently reappears suddenly - often in a difficult to reach place like the roof of a temple or the rafters of his home - dazed or unconscious, sleeps for days and then awakens as a halfwit and is generally unable to say exactly where he has been.*

*I, like so many others, am a big fan of Haruki Murakami, the author, and believe he should win the Nobel Prize for Literature. Some critics have said that he won't win because he is too Westernized. I think they are wrong. What they mistake for Westernization is simple modernization. At heart, he is Japanese through and through. The reason I mention this is because of one of his main characters in one of his major novels. This fellow shows remarkable similarities to the fantastical stories of the abductees. It is not a one to one comparison, but so what. Also, I won't tell you which character or which novel it is because I don't want to spoil it for you. You will just have to start reading Murakami for yourself and find out. That is, of course, if you don't already know. Otherwise have fun.

"If the child does not some back within the required time in response to the spells and the noise on the bells and drums, his relations must look for signs which will indicate that he has indeed been stolen by a god, and not simply been lost or drowned. In Shinshu province a sure sign that he has been stolen is to find his shoes neatly placed together under a tree. In nearly all districts a further proof of supernatural kidnapping is that he should be seen again briefly and mysteriously once." (Ibid. p. 113)

Not all abductors were kami. Some were simply hideous mountain creatures while others were tengu or.... you name it.

Women, too, would disappear mysteriously. But even stranger were the occasional sightings of these women and then their re-disappearance. [Is that a word? Probably not.] In the mid-19th century one young woman went out to gather chestnuts on a mountainside, but she failed to return. Her parents looked everywhere, but eventually gave up and performed funeral rites. Several years later a hunter ran into her and she told him "...she had been carried off by a terrifying creature, and had been living with him as his wife ever since. She was never given a chance to escape, and indeed any minute now he might come back. He was not unlike an ordinary man in appearance, except that his eyes were a terrible colour and he was immensely tall. [Many of the abductors were described as obscenely tall.] She had had several children by him, but always he had declared that because they did not resemble him they could not be his. In a rage he had taken them all away and presumably killed them." The hunter made a valiant attempt to return the girl to her village, but just as they approached its outskirts the creature bounded forth and took her back to the mountains with him. She was never seen or heard from again. (Ibid., pp. 114-5) |

|

Kamishimo |

裃

かみしも |

A costume worn traditionally by the samurai. In The Shogun Age Exhibition catalogue (entry #109, p. 129) there is a very striking image of an actual 19th century kamishimo. "The term is derived from the words kami (upper) and shimo (lower) and describes a garment of two such parts which have been designed to be worn together. In the Edo period members of the warrior class wore it as a ceremonial garment." For the daimyos and shoguns it was a 'simplified formal wear' and for those of lower social rank it was their Sunday finest.

|

|

"The kamishimo was the standard formal dress of the samurai. Bakama are worn as part of it, and kataginu, wide shoulder pieces which stand out stiffly and squarely on the wearer. This style of costume, it will be remembered, is also worn by theatre musicians..." The extended shoulders of the kataginu are said to be supported by hidden stays. Others say the shoulders are stiff from starching.

Quoted from: The Kabuki Theatre of Japan, by Adolphe Clarence Scott, published by Courier Dover, 1999, p. 141.

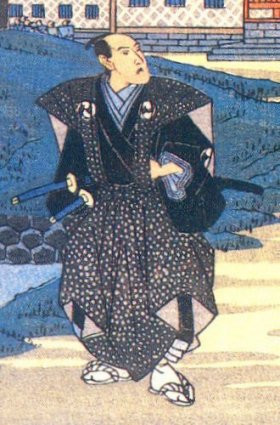

Note that in the illustration above on the right the stiffness of the kataginu is made even more evident by the movement of the kabuki actor. He has slipped his right shoulder free of this garment as he reaches toward his sword on his left. Another side note to this image is the presence of the pinkish inro shown hanging along his right hip. Inro rarely appear in ukiyo prints, but they do seem to show up more frequently in book illustrations like the one here.

"Kami-shimo are usually made of moro (linen), sometimes of silk and linen, occasionally all silk well stiffened with starch. The stuff is generally light-blue or brown, dyed in a small pattern on a white ground, with the family crest on the back and shoulders, either that of the wearer or his feudal lord."

Quoted from: Fu-so Mimi Bukuro: A Budget of Japanese Notes, by C. Pfoundes, published by the Japanese Mail Office, 1875, p. 145. (Note: As yet I am unable to confirm that moro is the word for linen.)

In The Kabuki Theatre by Earle Ernst (p. 122-3) the author notes that the musicians dressed in kamishimo often wear garments coordinated with the specific kabuki productions. In a famous act where the scenery is painted in pastel greens, etc., the kamishimo are green. In a winter scene the kamishimo may be white. "In Izayoi and Seishin the musicians are not conceived by the audience as a group of men who happen to be sitting along a river bank playing and singing; on the contrary, their relation to the play is the same as that of the Western opera orchestra to the action taking place on the stage. But they are visually related to the rest of the stage simply because the Kabuki is concerned with pleasing visual effect, and the repetition of the design and the colors of the setting on the musician's platform and on their kamishimo creates visual, not psychological, continuity. The platform on which the musicians invariably appear distinguishes them aesthetically form the area of the actor-dancer. Here, as elsewhere in the Kabuki, aesthetic differentiation is achieved through clearly defined spatial areas."

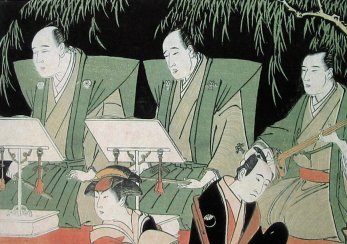

Below is a detail from a Kiyonaga print from the late 1780s showing two gidayu performers wearing green kamishimo. As noted in our entry on degatari these performers wear the same garb worn by samurai.

"The chanter acts like a fully trained actor who manifests the emotions of all the roles he alternatively impersonates. He wears a kamishimo ceremonial costume and squats on the stage-left podium behind the stand on which the text is always placed, even when not necessary for the performance, as is the case when the chanter is blind." (Quoted from: Japanese Theatre: From Shamanistic Ritual to Contemporary Pluralism by Benito Ortolani) The author also mentions that fact that there are occasions when the stage assistants wear all black kamishimo.

Karen Brazell notes in Traditional Japanese Theater: An Anthology of Plays that kamishimo are also worn during some Noh productions: as "...an indication that this is an important performance."

Arthur J. Bryant in his Samurai tells us that the kamishimo was "...the second most common apparel of the samurai."

In Modern Passings: Death Rites, Politics, And Social Change in Imperial Japan by Andrew Bernstein is an account of townspeople using attendants wearing kamishimo in a funeral procession. Clearly this had crossed the bounds of social correctness. "...when vulgar townspeople and entertainers die, they have attendants dressed in light blue kamishimo (formal samurai dress) march through two districts (chō) in double file. Is this not shameful to see?...This is wretchedness to be expected of the townspeople."

Before Tsunayoshi (綱吉: 1649-1709) became the fifth Tokugawa shogun he would dress in a linen kamishimo to visit the castle to ask about the health of his relatives and "...behave ceremoniously." (Source: The Dog Shogun: The Personality and Policies of Tokugawa Tsunayoshi by Beatrice Bodart-Bailey)

As the social barriers were being eroded in the late Tokugawa period there was an incident in Fukase-Mura in 1833 when "....twenty-six peasants submitted a petition to be able to wear formal dress (kamishimo) and to use 'house name'. The village head (shōya) first refused, but later approved." (Quoted from: Japan's Name Culture: The Significance of Names in a Religious, Political & Social Context by Herbert E. Plutschow) Later the author noted that in 1813 a daimyō in Mino province agreed to give successful peasants their own names and allowed them to wear the kamishimo. He also notes that "Impoverished daimyō sometimes allowed peasants to buy the right to use their surnames in public." It would seem that everything has a price.

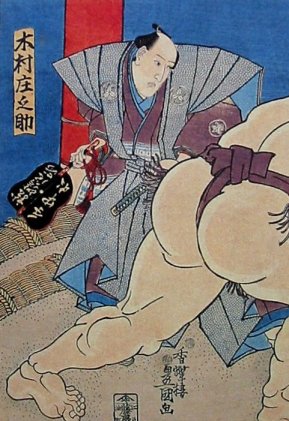

There is also a sumo official who wears the kamishimo. Below is a detail from the left panel of a Toyokuni III triptych showing an official dressed in a kamishimo during the Dohyōiri ceremony.

While we were researching this topic we kept finding references to the kamishimo as 上下. Japanese is a language layered with homonyms which are often used to give greater depth and complexity to their poetry, for example. In classical terms these homonymic references mean that a superficial translation rarely gets to the heart of the matter. Wit counted for so much more through innuendo. Perhaps that is why kamishimo could also be written as 'above and below' because of the nature of two part outfit. Kenkyusha's New Japanese English Dictionary partially defines 上下 'the upper and nether parts of the body'. That would explain Mock Joya's Things Japanese statement that "In Edo days, kamishimo (literally upper-lower) became the commonly used formal wear not only for samurai but also for many commoners. Kamishimo is so called because it is divided into two parts - the upper sleeveless coat and the lower skirt." Samuel L. Leiter and Benito Ortolani [see above] both use 上下 for kamishimo.

In Edo Culture: Daily Life and Diversions in Urban Japan, 1600-1868 Nishiyama Matsunosuke says that the noshime (熨斗目) is a "Plain kimono, with a striped pattern across the midriff, worn as an underrobe [sic] to the kamishimo and other formal garments." It is also referred to as a ceremonial 'underrobe'.

Townsend Harris mentioned kamishimo several times in his journals. In Townsend Harris; First American Envoy in Japan by William Elliot Griffis there is a footnote on page 106 defining kamishimo as "Literally, 'High-low,' a dress in old Japan corresponding to our 'evening dress,' worn alike by high officers, multi-millionaires, and by waiters and barbers."

William E. Deal in his Handbook to Life in Medieval and Early Modern Japan tells us that the kamishimo developed during the Azuchi-Momoyama period (安土桃山時代: 1568-1600*) and reflected Chinese and Portuguese influences. [*There are several variant dates given for the Azuchi-Momoyama period. We chose the one supplied by the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan.]

In Village Autonomy and Articulation with the State: The Case of Tokugawa Japan the author, Harumi Befu, tells us that "...ordinary peasants were not allowed to wear silk clothes or kamishimo..." as an economic imperative. Their existence was supposed to be based at a subsistence level reliant what they could grow and harvest.

In Bunraku or puppet theater the "Omozukai, the leader of the doll handlers, in contrast to the other members of the trio, wears kamishimo, the ceremonial dress of the theater, to show his rank as a master performer..." (Quote from: The Kabuki Theatre of Japan by Adolphe Clarence Scott)

It would appear that bridegrooms often worn the kamishimo during the marriage ceremony.

Marius B. Jansen in his The Making of Modern Japan cites the The Essence of Current Fashions which gives advice to the wearers of kamishimo: "Samurai are told how their kamishimo trousers should be stiffened with whalebone, with the outermost folds stitched down. The obi sash, they are advised, should be worn on the level of the navel with the front slightly elevated. Done right, it is known as a 'Bye-bye Obi' or 'Cat Teaser.' 'Curve your back a little to get the right effect,' goes the advice."

There is one more category where kamishimo appear occasionally and that is shini-e or memorial prints produced to commemorate the death of famous and beloved Kabuki actors. The one on the left and middle both date from ca. 1877 and are by Kunimasa IV and honor Bando Hikosaburō. The third example is by Kunisada from 1821 and is of Arashi Kitsusaburō.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Kamiyui |

髪結

かみゆい |

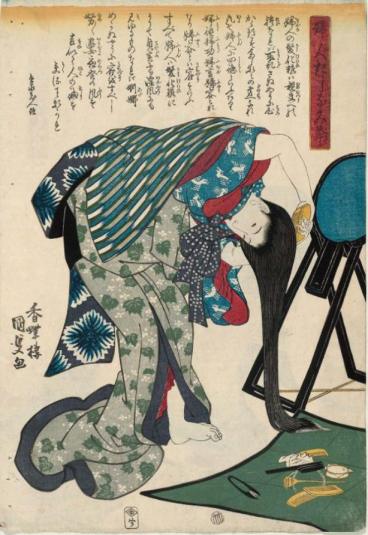

Hairdresser or hairdressing - Both examples shown here are from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Both are by Kunisada.

|

|

Kammuri |

冠

かんむり |

According to the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan (vol. 3, entry by Ishiyama Akira, pp. 118-19) there are three types of traditional Japanese headgear. One of these is the kammuri which translates literally as 'crown'. "Kammuri include highly ornate crowns decorated with gold and strings of beads as well as simpler caps of lacquered or soft fabric. In 604 noblemen were ordered to wear kammuri as part of their ceremonial or court dress following the Sui (589-618) China." In time the eboshi replaced the more formal kammuri. Worn during greetings, indoors and even while sleeping even though these 'crowns' served no practical purpose.

The image to the left is a detail from a Shigenobu print.

Note that the English spelling and the hiragana pronunciation differ slightly. This is a common occurrence when it comes to certain 'n' and 'm' sounds. Some sources refer to 冠 as kanmuri.

See also our entry on eboshi at our De thru Gen index/glossary page.

According to John K. Nelson in his Enduring Identities said that the kanmuri indicated a wearer's military standing. |

|

Kamuro |

禿

かむろ

|

Assistant trainee to a courtesan. Often viewed in Ukiyo-e prints wearing finery which matches that of the courtesan.

"Contemporary commentators did not consider it particularly inhuman or immoral to introduce children to prostitution; on the contrary, they judged early training as beneficial in the production of better courtesans." Girls as young as seven or younger were sought out by scouts. Kyōto girls were thought to be more graceful, but any beautiful child was considered desirable. "The children of famine-stricken peasants or debt ridden townspeople were especially susceptible to the enticements offered by brokers." Sometimes selling their daughters was the only way to raise money. The good daughter was the one who would acquiesce to such arrangements. The parents could console themselves with the fact that the child would be better fed and clothed. "The only path by which a woman could escape her low social and economic lot was the pleasure quarter."

Source and quotes from: Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan, by Cecilia Segawa Seigle, University of Hawaii Press, 1993, p. 81-2. 1, 2

|

|

"In the Yoshiwara a great supporting cast of servants, cooks, clerks, blind masseurs, storytellers, buffoons and other entertainers, supported the courtesans in providing happy times for their clients. Among this horde of helpers were youngsters of both sexes most of whom were little more than indentured servants. (Very young girls were sold by impoverished parents to Yoshiwara recruiters and held in bondage to be redeemed when sufficient funds could be raised for their freedom years later.) ¶ As previously mentioned, those meant to become courtesans were the kamuro. (Upon reaching the age of sixteen they were then known as shinzō.) Their training was strenuous and strictly disciplined as they served progressively as maidservants, messengers, and even as pets and companions until they reached their vocational goals. These young Yoshiwara apprentices wore a distinctive coiffeur and appeared encumbered in showy and elaborate dress. They are seen in prints attending to their various duties and accompanying beautifully caparisoned courtesans on leisurely strolIs within and outside the enclosures of the pleasure quarters... ¶ Young striplings, many the sons of courtesans, also grew up in the Yoshiwara acting as messengers, bearers of musical instruments, and performing such odd jobs as preparing tea for their superiors. These youthful male retainers were also titled kamuro." |

||

|

|

||

|

Kanagaki Robun |

假名垣魯文 かながきろぶん |

A major gesaku (popular fiction) writer of the last half of the 19th century. He worked closely with such artists as Kyōsai and Yoshitoshi. You can add to that list Yoshitora, Kunichika, Yoshiiku, Eitaku, Kuniteru, Kunimasa, Hiroshige III, Yoshitoyo, Yoshiharu, Yoshitsuya and Yoshibuna, et al.

The Encyclopedia Britannica says: "Kanagaki Robun, original name Nozaki Bunzō [野崎 文蔵], (born Jan. 6, 1829, Edo [now Tokyo], Japan—died Oct. 8, 1894, Tokyo), Japanese writer of humorous fiction who brought a traditional satirical art to bear on the peculiarities of Japanese society in the process of modernization. ¶ Robun began as an apprentice shop boy but became a disciple of Hanagasa Bunkyō, a writer in the gesaku tradition (writing intended for the entertainment of the merchant and working classes of Edo). Eventually Robun was recognized as a leading gesaku writer, noted for such works as Kokkei Fuji mōde (1860–61; “A Comic Mount Fuji Pilgrimage”), a satire of popular works on pilgrimages to famous places, and Aguranabe (1871; “The Beefeater”..." |

|

The Agura Nabe (安愚楽鍋) was a satirical look at the modern Japanese sophisticate, the 'beef eaters'. "The typical man of the day, he said was the "beef eater", a westernized swell with long flowing cologne-scented hair, calico underwear peeping from under his kimono, a gingham umbrella at his side, and a cheap Western pocket watch ostentatiously consulted from time to time. Sitting in a new style restaurant, he gobbled down a plate of beef, telling his neighbour how fortunate it was that "even people like ourselves can now eat beef, thanks to the fact that Japan is steadily becoming a truly civilized country"." Quoted from: Enlightenment of Women and Social Change by P.A. George, p. 17.

Kanagaki coined the phrase

katsureki or living-history play in October 1878. He had meant it

derisively, but in time it simply became the catchword for that genre.

"In 1874 Kanagaki Robun, realising that traditional gesaku prose (which had been his stock in trade) was becoming outmoded, announced he was becoming a journalist." Quoted from: Purloined Letters: Cultural Borrowing and Japanese Crime Literature, 1868-1937 by Mark Silver, p. 31. |

||

|

|

||

|

Kanban |

看板

かんばん

|

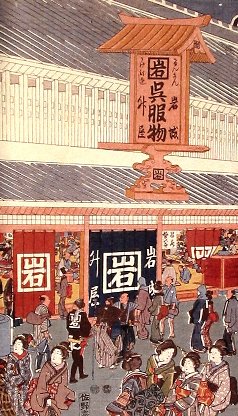

Signboard: As the merchant class, the lowest in Japan, began to prosper and the samurai, the highest, began to decline, the kanban became more and more common. Clearly businesses needed to advertise their wares or services in ways to attract the greatest number of clients. Signage became increasingly creative if not quirky. Often elaborate sign boards looked like the product being sold or something that came to be associated with that commodity. For example, tobacconists and pipe sellers might display a sign with a high relief, oversized pipe on it. The quality and distinctiveness of individual signs helped set businesses apart from one another in districts in which similar shops were clustered.

Some signs were equipped with roofs and/or shutters to protect them against the elements. Such architectural elements can be seen in the two Hiroshige details to the left. It has been noted that modern collectors and suppliers of theses signs often discard the extra architectural features. Too bad. (Source: Kanban: Shop Signs of Japan, published by the Japan Society in 1983) In the preface to this catalogue it says that kanban literally means "signboard". However, as we parse it the two kanji characters mean 'see' and 'board'.

Soba signboard at Chiba posted by d'n'c at commons.wikimedia.org

Detail from a Hiroshige print showing kanban at the Mariko station on the Tokaidō road.

There are also 'signboard girls', kanban-musume, which are attractive young women placed before business to draw in customers. James McLain in his essay in the Edo and Paris: Urban Life and the State in the Early Modern Era (p. 125) notes that "Young 'signboard girls' (kanban musume) stood outside on the roadway, where they displayed advertisements, implored passers-by to venture in for a cup of tea, and sometimes even physically dragged potential customers into the shops."

Today's rooftop signs meant to be seen at great distances are referred to as nikai kanban. Those projecting from a facade to be seen from further down a street are nobori kanban. Portable signboards are keitai kanban. Signs flush with the storefront are sage kanban. A signboard which uses an image familiar with a shops product is a yoki kanban. (Source: Japanese Love Hotels: A Cultural History by Sarah Chaplin)

This entry was prompted by a correspondence with David P. Thanks David. |

|

Kanbun |

漢文 かんぶん |

"Chinese readings; reading classical Chinese literature; Chinese prose and verse to be read in the particular Japanese way. Kanbun is not the Chinese language as it is spoken in China, but written Chinese to be read with the Japanese reading, the word order following Japanese syntax with specific Japanese particles... supplemented, and with the Japanese sound system." Quoted from: Dictionary of Japanese Culture by Setsuko Kojima and Gene A. Crane, p. 149.

"Centuries before Westerners arrived at Japanese shores the Japanese had already established contact with other Asian countries. According to Coulmas... it was through a Korean scholar that Chinese writing, the characters later to be called kanji, were introduced to Japan. Over time, the Japanese introduced changes to the syntax of written Chinese to make it usable as a means to transcribe Japanese, but not until the introduction of the kana syllabaries, especially hiragana, a natural transcription of spoken Japanese was possible... Before that, Chinese writing became one foundation of Japanese culture: it was kanbun, an often grammatically abnormal form of Chinese, which became the dominant means of written communication concerning scholarship, religion and literature, comparable to the status of Latin in Europe... While English is considered by many the language that moved Japan into the 20th century, it was Chinese which propelled it out of late. Stone Age." English in Japanese Language and Culture: A Socio-Historical Analysis by Kai Hilpisch, p. 6. |

|

Kane |

鉦 かね |

Gong - The metal gong is hit with a wooden mallet or shumoku (撞木).

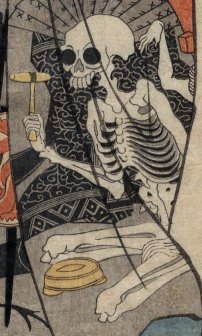

The image of the skeleton playing a gong come from a Kuniyoshi print in the Lyon Collection. To see the full image click on the picture to the left.

The photo above is from commons.wikimedia and was posted there by katorisi. |

|

Kan-ei |

寛永

かんえい |

The period, 1624-44, "...which marked the consolidation of the Tokugawa administration in fields both political and social, as well as the severance of diplomatic relations with most foreign lands. The city of Edo was developed into a center both of government and culture: Kabuki and jōruri theaters were opened (the 'Women's Kabuki' being banned and replaced by the 'Young Men's Kabuki'), and the Yoshiwara thrived (but still, more under samurai patronage than plebian), Kyoto remained the center of the arts, but Iwasa Matabei and his followers commenced the establishment of an Eastern ukiyo-e style. In book illustration, genre depiction began to replace the classical styles, and widespread publication (and primary education) made a new form of illustrated literature, the kana-zōshi, widely read among the masses. First experiments were made at color printing, but hand-coloring proved more practical for limited edition."

The image to the left is from a book on Nichiren from 1632. It shows the sainted man right after his birth. |

|

Kane no naru ki |

金のなる木

|

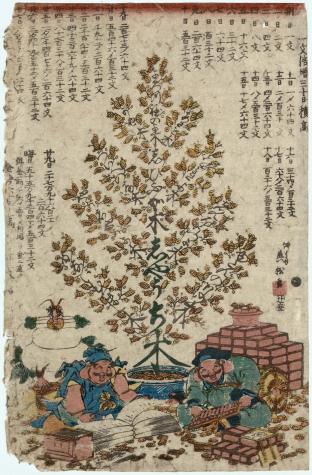

A money tree: The curatorial

files at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston say of the print shown to the left:

"In ukiyo-e prints, a money tree (kane no naru ki) is a good-luck symbol

consisting of a tree with coins for leaves, and a trunk and branches made up

of characters that spell out auspicious phrases all ending in the syllable “ki,”

a pun on “tree.” Daikoku and Ebisu, the gods of prosperity (associated with

rice and fish respectively) are usually shown beneath the tree. |

|

Kani |

蟹

かに |

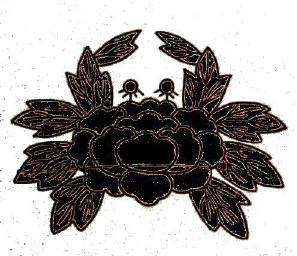

Crab motif used occasionally as a family crest or mon. Popular as a military mon its choice may have been due the the look of the crab itself - armored and in some cases powerful and painful in its attack.

The example seen to the left is one of those marvels common to Japanese design and in particular to the variations possible in their family crests. Here the crab is actually a budding peony plant. At least that is what I think it is. Notice how the eyes are buds getting ready to open. |

|

Kankan |

看看 かんかん |

An exotic regional 'snake' dance which was imported into Edo from Nagasaki in 1822. |

|

Now, you may be asking yourself "Why has he put that entry in here?" Well, I'll tell you. First, it is from an article by Andrew L. Markus published by the Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies and that accounts for its pedigree and second it struck me as an odd term which sounded too much like the Offenbach (オッフェンバハ)cancan. However, the fact that they are homonymous is strictly a coincidence. The coincidence is even more striking since they both refer to types of dances. Other than that they have no connection whatsoever.

Note: The Japanese character 看 means 'to watch'. Perhaps when doubled this has something to do with the exoticism of this style of performance - sort of like "You should see this!" However, I am just speculating here. Markus does add that this dance may be of Chinese origin. |

||

|

|

||

|

(Cancan) Read the entry above this one to see why we have put this here. |

カンカン |

A French dance made famous by the music of Jacques Offenbach (ジャック.オッフェンバハ) and the images of Toulouse Lautrec (トゥールーズ.ロートレック). |

|

Kanpyō (aka kampyō) |

乾瓢

かんぴょう |

Dried strips of gourd, used in food preparation, particularly in sushi. "Kanpyō is the cream-colored flesh of the white-flowered gourd yūgao, cut into very long thin strips and dried. Its best-known use is as part of the filling for makizushi, but it is also used in soups, aemono, and as an edible tie or string. In shōjin ryōri it is sometimes used to make vegetarian stock. In damp weather it easily goes moldy." Quoted from: A Dictionary of Japanese Foods: Ingredients and Culture by Richard Hosking, p. 72.

Above is a detail from an 1833-34 Hiroshige print from a Tokaidō road series. It represents Minakuchi and shows women cutting and preparing strips of gourd. The image to the left is of kobumaki posted at Wikimedia.commons by Ocdp. |

|

Kannushi |

神主

かんぬし |

A Shinto priest: "Kannushi is for kami-nushi, that is, deity-master. It is the most general word for Shinto priest. Properly it is only the chief priest of the shrine who is so designated. The Kannushi are appointed by the State. In early times their duties were performed by officials who already held secular posts. In 820 a decree was made prohibiting this practice, as it was found that such Kannushi neglected the care of the shrines of which they had charge. At the present time many Kannushi combine other avocations with their sacerdotal functions. The title may even be conferred on a layman by way of honour. The late famous actor Danjuro was an example. Kannushi are not exempted from military service. They are not celibates, and may return to the laity whenever they please. It is only when engaged in worship that they wear the distinctive dress of their office, which consists of a loose gown, fastened at the waist with a girdle, and a black cap called eboshi, bound round the head with a broad white fillet. Even this is not really a sacerdotal costume, but simply one of the old official dresses of the Mikado's Court. No special education is necessary for the discharge of the duties of a Kannushi, which consist in the recital of the annual prayers and in attending to the repair of the shrine." Quoted from: Shinto: The Way of the Gods by Aston. Published in 1905.

The image to the left was found at Pinterest. |

|

Kanreki |

還暦 かんれき |

"There being 12 animals, every 13th year has the same animal as its symbol. Then, the five elements of wood, fire, earth, metal and water are also given to five succeeding years in the order given. As both the 12 animal symbols and the five elements are used together for symbolizing years, there is obtained a common multiple of 60. So every 61st year has the same animal and element symbols. ¶ It is from this calculation that when a person reaches the 61st year the occasion is celebrated with much joy. It is called kanreki or return of the year, and the attainment of that age is regarded as a great event. It is commonly believed that on kanreki one will gain a new childhood or is reborn. Thus, on the occasion of celebrating the day, the old man or woman is the honored guest at a big banquet held by his or her children and grandchildren. The person is dressed in red-colored clothes and a red cap, as formerly it was customary to clothe newborn babies in red costumes. The kanreki festivity and its red costumes are still widely observed in rural districts. In cities too, children and grandchildren take much joy in honoring their parents or grandparents on their kanreki. Being the reborn child, the kanreki person has to obey the orders of the younger members of the family, moralists used to teach." Quoted from Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 331. |

|

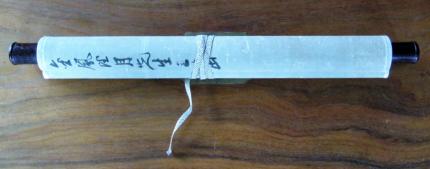

Kansubon |

巻子本

かんすぼん |

A scroll: "This kansu-bon format became the dominant form of both printed and manuscript books through the Nara, Heian and Kamakura periods. Yet it had one serious drawback: as it was used, it was unrolled and had to be rolled up again." Quoted from: The History of Japanese Printing and Book Illustration.

"...it is in this form that the book reached Japan and that books continued to be produced, exclusively so for several centuries..." Quoted from: The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth Century by Peter Francis Kornicki, p. 42. |

|

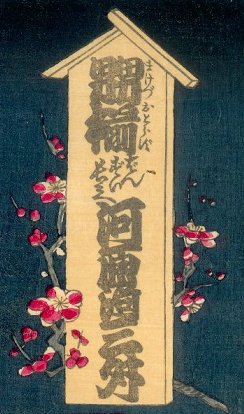

Kanteiryu |

勘亭流

かんてい.りゅう |

The calligraphic style of thick, rounded, crowded strokes commonly used by kabuki theater. Okazakiya Kanroku (1746-1805: 岡崎屋勘六)is credited with its creation in 1779.

According to the Kodansha

Encyclopedia of Japan (vol. 4, 1983 edition, p. 153) the Kantei style of

calligraphy originated in 1779 (An-ei 8 or 安永8年) with Okazakiya Kanroku

(岡崎屋勘六)an employee of the Nakamuraza (中村座). "Its

thick, curved strokes form compact characters with few open areas between

them, suggesting a 'full house,' and it quickly won favor in the theatrical

world. Easily recognized at a distance...[it is still used today]." It is

also used to announce the rankings of sumo wrestlers - although Leiter notes

that their is a slight difference in style.

|

|

Kantō daishinsai |

関東大震災

かんとうだいしんさい |

The Great Kantō earthquake of September 1, 1923. Not only was there an enormous loss of life and property but the immediate effect on artists like Hasui and publishing houses was devastating. (We will add more information eventually.)

To the left is a photograph of the remnants of the Shimbashi Station after the quake. |

|

Kantō hasshū |

関東八州 かんとうはっしゅう |

These were the 7 provinces in the Kanto region of the Edo period ruled over by Tokugawa Ieyasu after the battle of Sekigahara (関ヶ原) in 1600. They included Sagami, Musashi, Awa, Kazusa, Shimōsa, Kōzuke and Shimotsuke. Hitachi was a later addition. Of course, these is where Edo (now Tokyo) is located. |

|

Kantō/Kansai |

関東/関西 かんとう/かんさい |

While researching our entry for sekisho or barrier gate we ran across this passage about the Kantō and Kansai regions. It was a 'duh' moment. "East and West of the Barrier: Japan has a dozen or so area and geographical 'code words' that one must know in order to follow day-to-day conversation as well as business discussions. The two most common of these terms are kansai (kahn-sigh), which means 'west of the barrier,' and kanto (kahn-toe), which means 'east of the barrier.' ¶ Kansai, which is more cultural and historical in meaning than geographical, is loosely used in reference to the cities of Kobe, Kyoto and Osaka and the surrounding areas. Kanto refers to Tokyo and the surrounding area of the Kanto Plain." |

|

Kanzashi |

簪

かんざし |

Ornamental hairpin (See also our entry on kōgai.) 1

Lafcadio Hearn in his "A Letter from Japan" dated August 1, 1904 written from Tokyo relates a very pro-Japanese/anti-Russian sentiment. The two countries were at war, but Hearn dwelt on its psycho-social impact on the population in general. He even discusses the contemporary fashion for kanzashi: "The new hairpins might be called commemorative: one of which the decoration represents a British and Japanese flag intercrossed, celebrates the Anglo-Japanese alliance; another represents an officer's cap and sword; and the best of all is surmounted by a tiny metal model of a battleship. The battleship pin is not merely fantastic: it is actually pretty!"

Such elements showed up everywhere: towels, gift wrapping, toys, games, magic lanterns, clothes, undergarments and even the robes of little girls.

Source and quote from: The Writings of Lafcadio Hearn, edited by Elisabeth Bisland, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1922, pp. 343-50. |

|

"...a bodkin or ornamental hairpin with one or two prongs. The origins are unclear but because many had a small spoon for cleaning the wax out of the ears on the protruding end, it is sometimes suggested that it evolved from a tool for cleaning ears. The pronged ends could be used to scratch the scalp underneath elaborate chignons. Another widely-held theory is that kanzashi were created in imitation of the fashion among entertainers to stick branches of plum flowers in their hair. Yet another hypothesis suggests that the origins lay in sheathed knife carried by women of the warrior class to use in case of dire need... Regardless, after they appear in the late seventeenth century,they were common to all social classes..." Quoted from: Asian Material Culture, essay by Martha Chaiklin, p. 45.

Above is a kanzashi posted at commons.wikimedia by Kayopos. It was originally on a red ground. We changed most of it to black, but kept the red as a background for the pierced circular design. Notice the small spoon-shaped end piece.

"According to Baron Dan, a woman, 'sank into the depths of despair when one of her kanzashi slipped from its place in her carefully modeled coiffure and fell, broken, at her tiny feet!' Valuable items were repaired. For example, tortoiseshell was mended by melting the broken edges together with iron tongs." Ibid., p. 55 |

||

|

|

||

|

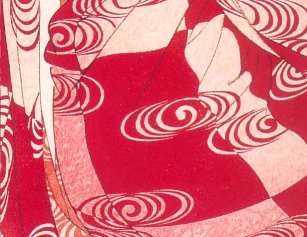

Kanzemizu |

観世水

かんぜみず

|

A water pattern with eddies. The top example to the left is from a detail of a Kotondo print and the bottom one is a detail from a Shoun (1870-1965: 山本昇雲) Merrily Baird in her Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design (p. 42) notes that this design represents the waters of rivers and ponds.

A note: I own several Japanese English dictionaries and kanzemizu does not appear in any of them. For that reason I am unable to determine how long this word has been in use. By way of analogy, perhaps the names given to decorative patterns are similar to the names given to flowers or varieties thereof. They may be too specialized to be found in the standard sources. |

|

Kaomise |

顔見世 かおみせ |

Anyone who studies Edo culture in general and the kabuki aspects in particular will run across the term kaomise frequently. It literally means 'face-showing' which is the Japanese expression for the debut of the new theater season.

"'Face-showing performance,' an annual Edo period production at which a theatre announced its newly engaged company of actors and they performed together for the first time. It was considered the most important production of the season." It was the custom for these actors to stay together in one theater for a full year. "On the last day, a closing announcement was made along with a declaration of what the next production and cast list would be..." ¶ "At kaomise time, the front of the theatre was piled high with gifts of rice and sake form supporting organization (hiki), forming a decorative background (tsumimono)."

Source and quotes from: New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of kabuki jiten, compiled by Samuel L. Leiter, 1997, p. 282. |

|

Kappa |

河童 かっぱ

|

Literally kappa means child 童 of the river 河. However, Michael Dylan Foster, mentioned below notes that the term kappa is originally from the Kantō region, but has over 80 different regional variations. Some of the names make reference to the fact that these creatures remind some people of children (kawappa, kawako), others of monkeys (enkō), still others of soft-shell turtles (dangame) and even otters (kawaso). Sometimes its name relates to one of its personality traits like that of a 'horse puller' or komahiki.

Above is an image of a kappa by Kunisada. He is wearing a robe decorated with cucumbers, his favorite food. I added the green coloring. There is more about kappas and cucumbers on our Kappa Control page.

Nasty little supernatural creature which wreaks havoc with humans and other animals. Noted for the bowl shaped indentation in the top of their heads which holds water and is their source of strength. Oh, yeah, they are also fond of wrestling.

This image above to the left is from the Mike Lyon Collection. Click on it to see the whole print. For more about kappa control click on the yellow #1 to the right. 1 |

|

In their new book, Yokai Attack: The Japanese Monster Survival Guide, Matthew Alt and Hiroko Yoda, provide a ton of information which one would need if one were ever to encounter any of these unpleasant nasties. Gender: male. For some reason there don't seem to be any girl kappa. Height: 3' to 5'. Weight: 65 to 100 lbs. Among their stranger features is a removable skin and three anuses. Why? Haven't the slightest. Weapons include extendable arms and extreme flatulence. Weaknesses include a strong dislike of "...iron, deer antlers, and monkeys." Alt and Yoda tell us that kappa are "Easily the single most famous yokai in Japan. They smell like "...rotting compost." Parents warn their children to stay away from lakes and rivers. [A friend of mine even says that signs are posted near ponds warning of kappa sightings.] "According to one story, some nine thousand of the creatures swam en masse from China to Japan around the fifth century..." They are generally innocuous unless pissed off. However, there are exceptions to this too. They are apt to challenge passersby to "...mano a mano wrestling matches..." Drowning victims are often the not just drowning victims. They were dragged under by kappa who naturally are great swimmers. But it is their habit of reaching up through one's anus and removing one's intestines which is probably their most disturbing trait. [Some accounts say that they can suck the liver right out of a person through the anus. Ick!] "The kappa isn't after the entrails themselves, but rather the shirikodama, a mysterious organ said to be located in the colon." Notice that kappa have an indentation in the top of their heads which holds water. Get it to spill out and they are basically powerless. ¶ If challenged to a wrestling match don't fight it. Get them to bow in the hope they will spill the water on their head. Wrestle them in the sunlight. This will speed up evaporation. And, if all else fails, throw a cucumber at them. They are suckers for cucumbers - their favorite food. ¶ "Kappa must leave the water and remove their waterproof skin - called amagawa - in order to sleep. A kappa without its amagawa is totally defenseless: it can't enter the water without it! Because of this raincoats are also known as amagappa in Japan." ¶ One last thing: There is a Japanese saying: He no kappa which means "Like a kappa fart." Alt and Yoda say this is the equivalent to the American saying "Piece of cake."

One more, one last thing: For more about kappas and flatulence in general in Japanese society go to our page devoted to our Yoshitoshi print we call "Kappa control".

Michael Dylan Foster in his article The Metamorphosis of the Kappa: Transformation of Folklore to Folklorism in Japan argues that viewing these creatures as cute, cooperative or amusing is basically a modern invention. In all earlier references kappa are just plain nasty and threatening. According to first hand reports the kappa range in size from those comparable to a child of 3 or 4 up to about 10. They have been described as being covered with hair or scales. "The kappa smells fishy, and in color is often blue-yellow, with a blue-black face, but there are countless variations of these elements. Almost always the kappa has a carapace on its back, and its face is sharp with a beak-like mouth." ¶ The hollowed-out area on the top of the kappa's head is called a sara (皿) which literally translates as 'plate' or 'dish'. It "...contains a liquid usually described simply as water, although the exact composition of the fluid is not always specified. But, whether it is water or some other liquid, it represents the life force of the kappa; if it dries up or spills, the kappa loses its power, and—in some accounts—dies. Many legends about the kappa refer to this sara and the potency of the liquid it contains." ¶ Foster tells of a legend from Okayama prefecture in which a group of children are practicing sumo by a river. Another child comes up and wants to join in. They realize that he is a kappa so they all shake their heads and the creature does the same losing its strength and is forced to leave. That bow performed by sumo wrestlers is often the downfall of the polite kappa competitor. ¶ We have mentioned elsewhere how cucumbers or kyūri (黄瓜) are the favorite food of kappa. Foster adds to this list nasu (茄子) or eggplant, soba (蕎麦) or buckwheat noodles, nattō (納豆) or fermented soybeans and kabocha (南瓜) or pumpkin. ¶ Kappa aversions include gourds or hyōtan (瓢箪), sesame, ginger, saliva and iron. But iron is not such a strange thing because all water spirits hate iron. In fact, Edward Burnett Tylor wrote in 1922 that "The Oriental jinn are in such deadly terror of iron, that its very name is a charm against them; and so in European folklore iron drives away fairies and elves, and destroys their power." European witches could be kept at bay by iron implements and particularly by horseshoes. That is said to be the reason so many of them could be found nailed to barn doors.

Mock Joya speculated that the origin of the kappa came from misidentified suppon (鼈) or snapping turtles. (Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 412)

"A Poem of Michizane was held in great esteem in Kiushu as a protection against the Kappa..." Quoted from: Legend in Japanese Art by Henri Joly, p. 36.

Two contemporary testimonials: 1) A number of years ago a friend of mine who spends much of his time in Japan says there are still signs warning people not to swim in local ponds because there are kappas there; 2) On November 27, 2011 Hank wrote to say that a lady friend of his in Japan says that kappa "....would swim up the toilets and pinch the ladies on the bottom." Good thing I am not a lady and a good thing I don't live in Japan - at least, for that reason. Other than that... Sigh!

Kappa are also referred to as kawatarō (河太郎).

Janine Beichman in her Masaoka Shiki: His Life and Works (p. 40) quotes a haiku by Yosa Buson (与謝蕪村: 1716-1783):

Henri Joly wrote: "The Todo Kimmo Dzue gives it the name Kawataro (compare the Osaka form, Gataro), and describes it under the name Suikō (water tiger): 'It is like a child of three or four years, with scales all over its back. It lies on the sand, looking like a tiger; it has long claws which it hides in the water, and it will bite little children if they touch it.' ¶ In the river of Kawachi Mura a Kappa was caught by the belly-band of a horse, and after being rendered harmless, as above described, was made to sign a bond not to attack thereafter any man, woman, child or beast." Quoted from: Legend in Japanese Art, p. 161.

In the 1886 Descriptive and Historical Catalogue of a Collection of Japanese and Chinese Paintings in the British Museum by William Anderson it says: "...the Tōdo Kimmō dzu-i, a kind of pictorial cyclopædia of Chinese objects, published in Japan in 1802."

"...the kawatarō is the only creature completely bereft of documentary evidence or links with a Chinese precedent." Quoted from: Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese Monsters and the Culture of Yokai by Michael Dylan Foster, p. 46.

Yanagita Kunio once wrote: "...gataro [another name for kappa] were the sole topic of our conversations at elementary school." Quoted from: The Culture of the Meiji Period by Irokawa Daikichi, p. 21.

"The kappa is one of the most wide-ranging and oldest yōkai: a kappa-like creature even appears in the early mytho-historical Nihonshoki (720). Like most folkloric monsters, the kappa varies significantly with historical and geographical context. Having said that, they are almost always portrayed as small anthropomorphic creatures that live in the water, usually a river or pond. They can be deadly, with a penchant for pulling horses into the water, drowning small children, and reaching up through a victim's anus to extract the liver or other internal organ. Or they can simply be mischievous: during the Edo period, they were occasionally found lurking in outhouses, where they would reach up to stroke the buttocks of unsuspecting occupants." Quoted from: The Ashgate Research Companion to Monsters and the Monstrous, p. 143.

|

||

|

Kappazuri |

合羽摺

かっぱずり |

Stencil print - "Compared to the complex nishiki-e produced in Edo, Nagasaki prints were technically crude and unsophisticated. Their origins lay in Chinese New Year prints produced cheaply in Suzhou, which may explain the technical differences between Nagasaki and Edo prints. In both cases the earliest form was a black outline which was then hand-coloured. Edo, however, moved on from hand-colouring to the kentō registration system whereas in Nagasaki a stencil method (kappazuri) was used. A stencil for each colour was cut out of thick paper, placed over the black outline and the colour applied with a stiff brush. The coloured areas are not as accurately registered within the black outline as with the kentō method and inevitably a thick ridge of colour builds up at the edge of each stencilled area as it is brushed. Compared to the Edo multicoloured method, stencilling gives the print a coarser, more handmade feel. Stencilling is a technique commonly used in textiles and it is still employed today in the production of playing cards... This may well be because European cards entered Japan through Nagasaki and that area became the initial centre of production. Not all Nagasaki-e were produced with this stencil method however; possibly through the migration of craftsmen, the Edo registration technique also came into use." Quoted from: Japanese Popular Prints from Votive Slips to Playing Cards by Rebecca Salter, pp. 82-83.

The image above by Nagahide was posted at Wikimedia commons by William Pearl. |

|

LINKS TO OUR OTHER INDEX/GLOSSARY PAGES Click on any of the pages listed below!

|

||

_by_Nagahide_commons_7b.jpg)

HOME

HOME