JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

Hil thru Hor |

|

|

The molecular model on Lonsdaleite was used as a marker for new additions from January 1 to May 31, 2021. |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Jack Hillier, Hime kaidō, Hinagatabon, Hineno-jokoro, Hinoe-muma,

Hi no maru,

Hishi manji, Hitodama, Hitotsu-me-kozō, Hitsu, Hi watari, Ho, Hōgu, Hōjō-e, Hōju, Hōkaburi, Hōki, Hokuei, Hokuto shichisei, Hōmongi, Hōmyō, Hondawara, Honden, Hōnoki, Hō-ō, Horagai, Hōrai, Hori, Hori Asa, Hori Chō, Hori Chōsen, Hori Dai, Hori Ei, Hori Kane, Hori Ken, Horikō Fusajirō, Horikō Gin, Horikō Hidekatsu, Horikō Ko-kin, Hori Koma, Horikō Masu?, Horikō Masukichi, Hori Renkichi, Horikō Shige, Horikō Shinchō, Horikō Tashichi, Horikō Yamaichi, Hori Masa, Hori Mino, Horimono, Hōrin, Hori Ōta Tashichi, Hori Sashichi, Hori Sennosuke, Hori Shōji, Hori Take, Hori Takichi, Hori Toyo, Hori Uta, Hori Yasu, Hori Yata, Horo, Horogaya

姫街道, 雛形本, 丙午, 日乃丸,

蛭子, 菱卍, 人魂, 一つ目小僧, 筆, 火渡り, 帆, 法具, 放生会, 宝珠, 頬被り, 帚, 北英, 北斗七星, 訪問着, 法名, 馬尾藻, 本殿, 朴の木, 鳳凰, 法螺貝, 蓬莱, 彫, 彫朝, 彫長, 彫大, 彫栄, 彫金, 彫兼, 彫工房次郎, 彫工銀, 彫秀勝, 彫工小金, 彫駒, 彫工舛吉, 彫工繁, 彫工深長, 彫工多七, 彫工山市, 彫巳の, 彫物, 宝輪, 彫太田多七, 彫廉吉, 彫千之助, 彫佐七刻, 彫庄次, 彫竹, 彫多吉, 彫豊, 彫卯多, 彫安, 彫弥太, 母衣, 母衣蚊帳 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Hillier, Jack |

ジャック.ヒリアー |

Author of Art of the Japanese Book. |

|

Born in Fulham, England in 1912 the son of a postman who delivered mail to Sir Edward Burne-Jones (エドワード・バーン=ジョーンズ) , Rudyard Kipling's (ラドヤード・キップリング) uncle by marriage. Hillier died in Surrey in 1995. From a poor, but happy family he toyed with the idea of becoming an artist - even learning wood engraving - but decided on a more practical route and took a job with an insurance company. He stayed with them until he was 55. During WWII he applied to the RAF to become a pilot, but was rejected for that position because of his somewhat impaired eyesight. However, he did work as an aircrew instructor and in the signal corps.

In an obituary in The Independent he was referred to as the "... leading authority in Europe on the Japanese woodblock print" and other areas. His interests in the field began in 1947 when he bought a portfolio of Japanese prints - some facsimiles. At that time Japanese studies were probably at their ebb. Hillier realized that he would have to learn Japanese so he studied the Harvard-Yenching Course during his train commutes to and from the office.

In time he was invited by Sotheby's (サザビーズ)to be one of their experts. For more than 25 years while working there he assisted in the development of numerous prominent collections: that of Chester Beatty (チェスター・ビーティー), now bequeathed to the Irish state; the Gale collection in Minneapolis; Ralph Harari's collection; et. al. Hillier's first book on the subject, Japanese Masters of the Colour Print, was published in 1954 followed by many other including works on Harunobu, Hokusai, Utamaro, drawings, paintings, etc.

He was a great scholar and connoisseur who made an incredible addition to the field. |

||

|

|

||

|

Hime kaidō |

姫街道 ひめかいどう |

"Travel by boat was more dangerous than going overland. In fact, not traveling by sea was one of the precepts the doctor Tachibana Nankei (1753- 1805) followed when away from home. The alternative, land routes, however, were circuitous and therefore took longer. Two routes connected to the Tōkaidō, the Sayaji and the Honzaka dōri, were also dubbed "hime kaidō" (lit., "princess roads"), supposedly because women, having less "stomach" for water travel, opted for them more often than did men." Quoted from: Breaking Barriers: Travel and the State in Early Modern Japan by Constantin Vaporis, p. 35. |

|

Hinagatabon |

雛形本

ひながたぼん |

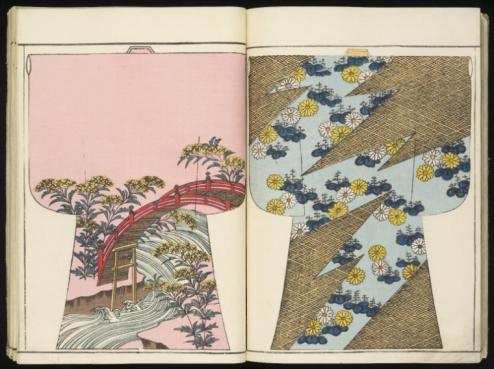

Kimono pattern book(s): We have seen dozens of these which were almost exclusively from the Meiji and Taisho periods. Each page was filled with a typical image: autumn leaves floating on swirling waters; birds in flight; chrysanthemums; etc.

Hinagatabon also referred to "...instruction manuals for builders and artisans..." These volumes exist all of the way back to the 16th century. (Source: "Patronage and the Building Arts in Tokugawa Japan" by Lee Butler)

The image to the left comes from the University of Edinburgh via Pinterest. |

|

Hineno-jokoro |

ひねのじころ |

Neck-guard on a samurai helmet |

|

Hinoe-muma (or hinoe uma) |

丙午 ひのえむま (or ひのえうま) |

"...the Fiery Horse... It was widely believed that women born in the year of the Fiery Horse (one of the 60 recurrent combinations in the Chinese Zodiac) would kill their husbands. The belief persists today in certain regions." Quoted from: Footnote 168, The Life of an Amorous Woman: And Other Writings by Ihara Saikaku, p. 315. |

|

Hi no maru |

日乃丸

ひのまる |

The Japanese national flag: Generally represented as a red disk on a white field often it is seen on a black field on a fan or ogi. "It is popularly known as the Hinomaru (Sun Flag). The design has been a popular one, although it is not known when it was first used." Supposedly when the Mongols were threatening an invasion of Japan the priest Nichiren gave a rising sun flag to the shogun. (Quote and source: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan entry by Yukihisa Suzuki, vol. 5, p. 339)

U. A. Casal in his "Lore of the Japanese Fan" (Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 16, no. 1/2, 1960, p. 81) spoke of a sun design on Kamakura period (1185-1333: 鎌倉時代) fans: "A favorite décor was a blazing golden sun on a scarlet ground, an ancient warrior symbol.... Their resplendent colours must well have matched the gorgeous armour and brocades of the Kamakura lords.

There were naturally, some variations in these warrior fans too. A red sun may appear on a black or fully gilded ground, or even more conspiciously on a white one, although white could not be lacquered. Such warrior folding-fans are generally referred to as tessen [鉄扇], 'iron fans'. For ordinary use, however, the warrior had similar fans - also with the sun emblem, and sometimes with the moon and stars on the back - of a black lacquered wood or bamboo frame, known as gunsen [軍扇] (war-fan). The martial fans always had eight or ten ribs." |

|

In footnote 30 Casal wrote: "Only at the time of the [Meiji] Restoration [in 1868] was the sun-symbol of Victory transformed into a Japanese national flag of a red sun on a white field. In feudal days any colour combination might be chosen, though red was prevalent, either as 'sun' or as 'field'. The Sun with Rays (Naval flag) did not exist before the Restoration..."

"The history of the Hinomaru is supposed to date back to the time of the Mongol invasions of Japan (1274 and 1281) when the priest Nichiren gave the Shogun a rising sun flag. Toyotomi Hideyoshi used this flag in his invasion of Korea in 1592 and 1597 and, as more Western ships began to appear in Japanese seas in the mid-nineteenth century, it was suggested that all Japanese ships should fly the Hinomaru for identification." (Quoted from: Case Studies on Human Rights in Japan by Roger Goodman and Ian Neary, p. 77) In 1870 it was designated as the national flag by 'declaration'. However, it seems to have had a difficult legislative life and in 1931 it was put forward again as the national flag by the House of Representatives, but this was rejected by the House of Peers. (Ibid., pp. 77-8) "...the Hinomaru is referred to as kokki [国旗], the national flag..." (Ibid., p. 82)

Other trace its history back to Monbu, an 8th century emperor. Also, different color variations when used as military insignia in the 15th and 16th century indicate different warring factions or clans. "...in 1853, the militias of two feudal lords fought and killed some sailors from the Royal Navy of England. One of the clans, the Satsumas, fought under the Hinomaru, and the English mistakenly assumed that this was their national flag." (Source and quote: Do Elephants Jump? by David Feldman, p. 152) "...the first time the Hinomaru was flown at a national ceremony was in 1872, on the occasion of the opening by Emperor Meiji of Japan's first railway." (Ibid., p. 153) The Imperial Navy began flying the 16 spoke flag in 1889, but quit using it with their defeat in 1945. (Ibid.) The Hinomaru was not adopted as the national flag until 1999. (Ibid., p. 154)

There are other versions of the origin of the national flag as can be found in Little-Known Wars of Great and Lasting Impact by Alan Axelrod on p. 54: "While it is universally acknowledged that the flag represents the rising sun, an image that has always resonated powerfully in Japanese religion and culture, little is known about the historical origin of the flag, except that its colors are those of the Minamoto clan. There is a widely revered legend that the modern Hinomaru was presented to the samurai Minamoto no Yoshimitsu by the Emperor Reizei. Tradition hold that the flag today enshrined at the Unpo-ji temple in Yamanashi Prefecture is that very treasure."

Modern Japanese flag posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Zscout370.

Takashi Fujitani has written about the historical significance of this flag in his Splendid Monarchy: Power and Pageantry in Modern Japan (p. 49): "The Rising Suns gracing Japan's national flag and the hinomaru lanterns had an even longer history of association with the imperial household than the chrysanthemums did; but like the floral emblem, the rising sun had no exclusively national or imperial meaning for most commoners until the modern era. Japan had no national flag until 1854, when upon a petition by the lord of Satsuma han, Shimazu Nariakira, the bakufu determined that Japanese ships should fly a white flag bearing the Rising Sun emblem in order to identify themselves as Japanese."

One older source from 1914 says the flag was adopted for shipping in 1859. It also noted that there were 16 rays emanating from the center as there are in the flag shown below. "The number is believed not to have been selected at haphazard, since it is one of those produced by multiplying two by itself, of which there are examples in the four cardinal points; the 8 kwa, or diagrams, of Chinese philosophy; the 32 points of the compass..." (Source and quote from: Terry's Japanese Empire... by Thomas Philip Terry, 1914, p. cliv)

The Nisshōki (日章旗) is the Rising Sun flag. Below is an example posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Penubag.

According to the Japan Encyclopedia by Louis Frédéric the Hi-no-maru was used by Takeda Shingen, Uesugi Kenshin, and Date Masamune. (p. 549)

See also our entry on kyokki on our Kutsuwa thru Mok page. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

平仮名

ひらがな |

Cursive Japanese syllabary used primarily for native Japanese words (esp. function words, inflections, etc.): With its rounded shapes it stands in contrast to katakana which is sharp, angular lines. Although hiragana evolved from the 8th century on it did not appear in printed form until the time of Hon’ami Kōetsu (本阿弥光: 1558 – 1637), an artist of great renown. According to Hisako Kobayashi: "Kōetsu printed the classical Ise Story 伊勢物語, Hōjōki 方丈記, and Tsurezuregusa 徒然草 and others using hiragana (Japanese syllabary characters), and not kanji (Chinese characters). This was the first time for hiragana to be used for printing, and it marked a memorable turning point in printing history because few people could read kanji."

To the left is an image of two pages published in ca. 1610. It reproduces the calligraphic style of Koetsu in printed form. From the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It represents two of the 36 Immortal Poets. |

|

Hirauchi |

平打ち広 ひらうち 重 |

A type of kanzashi - "It consisted of two prongs with a large flat piece in the form of a disk, diamond, hexagon, flower or other shape. Women of the warrior class usually wore these made of silver or some silver-like metal. The flat surface was frequently embossed or chased and often had a family crest. The two prongs were so that if a woman, who in the warrior class might be trained in combat, was attacked, she 'was to pull out the hairpin and stab her assailant in the eyes with the two-pronged end'... When this type of ornament spread to the demi-monde, it became the fashion for the women there to put the crest of their house or that of their wealthiest patron. Conversely, patrons might have the comb or kanzashi with the crest of their favorite courtesan to advertise their intimacy. Pretentious men might obtain such a comb without ever even having been associated with the courtesan in question. The ornaments were valued because their possession of this sort of very personal object implied intimacy." Quoted from: Asian Material Culture, essay by Martha Chaiklin, p. 49. |

|

Hiroshige, Ando |

安藤広重

あんどうひろしげ重 |

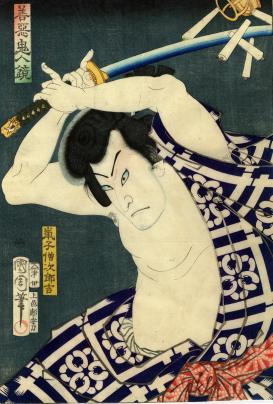

Hiroshige (1797-1858)

Definitely one of the greatest artists of the 19th century, but I am not telling you anything am I?

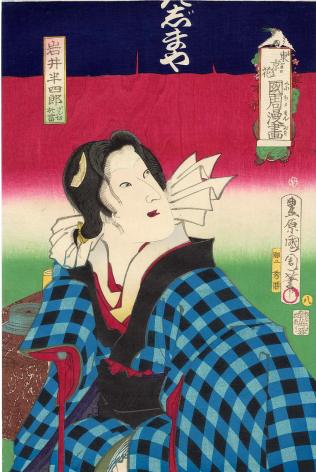

The memorial portrait of Hiroshige to the left is a detail from a print by Toyokuni III. |

|

Hiruko |

蛭子 ひるこ |

The leech child |

|

I am currently reading a novel by an important contemporary Japanese writer. (I will leave him unnamed so I don't spoil the book for those of you who haven't read it yet.) In one exotic scene "Suddenly, unfamiliar greasy objects began to rain down from the sky... There weren't any clouds, but things were definitely falling, gradually more and more fell, until before they knew it they were caught in a downpour." It was raining leeches! What struck me most about this passage was not the bizarre imagery, but the mythico-historic link to the Japanese past.

In the Kojiki (古事記: 712), the oldest written chronicle of Japanese literature, the gods Izanagi and Izanami mate, but their first efforts resulted in the leech child "...an amorphous blob, which even at the age three cannot walk.... Realizing that something has gone wrong, abandon the failed offspring in a reed boat onto the ocean and try again." This miscarriage was soon identified with "...failed crops, bad fishing and disorder..." and outcasts. In time hiruko evolved into Ebisu, one of the Seven Propitious Gods. In fact, Ebisu's name is written with the same kanji characters - 蛭子 - although it is pronounced differently. The connection is unmistakable.

An alternate use of kanji characters - 恵比須 - also is pronounced as Ebisu. (Source of the second group of quotes is from Puppets of Nostalgia by Jane Mari Law, Princeton University Press, 1997) |

||

|

|

||

|

|

菱卍 ひしまんじ |

A lightning and swastika motif - "The stage costume for Fuwa Bavaemon was first established by Ichikawa Danjūrō I. It is decorated with lightning bolts forming the hishi manjí (diamond swastika) motif, emphasizing his strong and wicked character."

See also our entry on kumo ni inazuma. |

|

Hitodama |

人魂

ひとだま

|

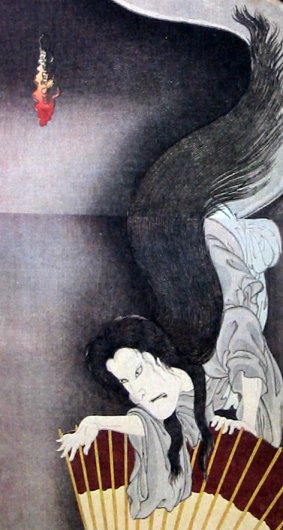

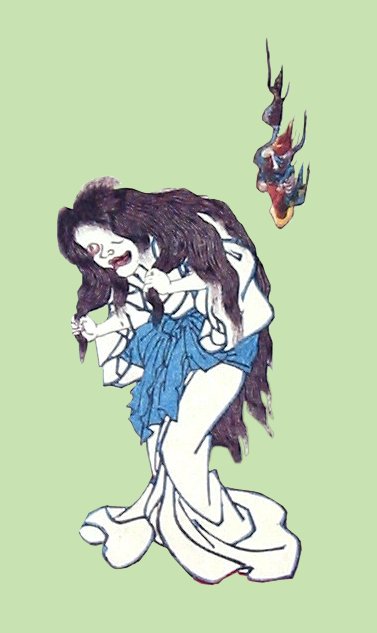

Disembodied soul; supernatural fiery ball: Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary, 1954, p. 445 translates hitodama as "...a jack-o'-lantern; a will-o'-the-wisp; ignis fatuus; a death fire; a fetch candle; ...a wraith; a doubleganger."

The Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan entry by Inokuchi Shoji (vol. 3, p. 207) describes hitodama as "The spirit that is supposed to depart from the human body at the time of death and afterwards, commonly believed to take the form of a bluish white ball of fire with a tail. Seeing hitodama was traditionally regarded as a premonition of one's own death, although various ways of exorcising them are mentioned in medieval literature. Even today one hears of people who claim to have seen hitodama hovering over rooftops or in graveyards at night. Shooting stars, phosphorescence, and other natural phenomena are sometimes taken for hitodama."

The detail to the left above is from a vertical triptych by Kunichika. The image shown below is a detail from a print by Kunisada showing the ghost of Oiwa with her associated hitodama.

For another related example of free floating flames see our entry on kitsunebi on our Kesa thru Kuruma index/glossary page. See also our entry on reikon.

The flame to the left is a detail from a Yoshiiku print. |

|

Hitotsume-kozō |

一つ目小僧

安ひとつめこぞう重 |

One-eyed temple monster or goblin. Louis Frédéric in the Japan Encyclopedia says: "...a sort of demon (oni) or ghost (bakemono) with one eye in the middle of its forehead. This cyclops is often associated with a young Buddhist monk (kozō), or, in Shinto, with a Ta no kami (or Yama no kami). It is sometimes portrayed holding a grill with charcoal in its hand. People protect themselves from its spells by placing an upside-down basket on top of a pole in front of the house, especially on kotoyōka days (eighth day of the second and twelfth lunar month.)

Michael Dylan Foster has written a fascinating passage which is devoted as much to the hitosume-kozō as it is to the method developed by Kunio Yanagita (柳田國男: 1875-1962): "An early example of Yanagita's approach is found in a 1917 essay 'Hitotsume-kozō' (One-Eyed Rascal). The essay concerns hitosume-kozō - a small anthropomorphic creature with one eye, one leg, and a long tongue - of which Yanagita notes, 'with only a little variation, this yōkai has traversed most of the islands of Japan. Particularly noteworthy, he points out, is that there is little evidence of its diffusion as a legend by word of mouth; rather, it seems to have emerged similarly throughout the country (a case of what folklorists would call 'polygenesis'). Presenting a 'bold hypothesis', Yanagita argues that the tradition of hitotsume-kozō represents a trace of earlier customs involving human sacrifice." (p. 145) ¶ Yanagita proposed that in ancient times individuals were chosen by 'divine' selection for human sacrifice. One year before their final demise they would have one eye poked out, but from there on would be treated with respect and honor because they held a sacred position within the community. Long after the practice of human sacrifice ceased the concept of the one-eyed figure remained in one form or another. "Many generations later, this conflation of one-eyedness with the sacred, and with the status of a sacrificial victim as a doomed outcast, would survive in the form of the yōkai hitotsume-kozō." (p. 146) ¶ Foster quoted Yanagita: "Like most obake, hitotsume-kozō is a minor deity divorced from its foundations and lost its lineage.... At some point in the long distant past, in order to turn somebody into a relative of a deity, there was a custom [fūshū] of killing a person on the festival day for that deity. Probably, in the beginning, so that he could be quickly captured in the event of an escape, they would poke out one eye and break one leg of the chosen person." Much later "...it was long remembered that the sacred spirits [goryō] of the past had one eye; so when the deity became separated from the control of the higher gods and started to wander the roads of the mountains and the fields, it naturally followed that it came to be seen as exceedingly frightening." (Ibid.)

A personal note from this writer: I would much rather have been chosen as the virgin to be thrown into the volcano as seen in so many early 20th century movies than to have been made into a hitosume-kozō. At least the volcano ordeal would have been over in a flash, so to speak. |

|

The modern hitotsume-kozō, as described in Hiroko Yoda and Matt Alt's book Yokai Attack: The Japanese Monster Survival Guide, is a male figure, bipedal, with a shaved head and about as tall as a 7 or 8 year-old boy. Dressed in traditional garb with one glowing eye it can be found anywhere humans are. They like to jump out of the shadows to scare people or even sneak into their homes to scare the bejeezus out of them. Don't forget the monster's preternaturally long tongue. They are also frequently seen carrying a Buddhist's rosary beads.

In 1875 in Fu-so mimo bukuro: a Budget of Japanese Notes by C. Pfoundes describes the Shitotsume kozo which must be the same creature covered here. There it says that this "...is a one-eyed ghoul wearing a large hat, carrying in the hand a small sieve containing a ball of fire, the sight of which strikes terror into the beholder." |

||

|

|

||

|

Hitsu |

筆

ひつ |

"From the brush of" - a common ending following the artist's signature. The other most common ending is ga (画). 1 |

|

Hi watari |

火渡り

ひわたり |

Fire walking: "The second group of powers is practised only by yamabushi and consists not so much of practical accomplishments as of demonstrations of the magic art, undertaken to convince the community that the disciple has indeed risen above the ordinary human state. Until the end of the last century a fair number of these feats could still be witnessed in various parts of Japan. Today the repertory seems to have been reduced to three: hi-watari or firewalking, yudate or sousing oneself in boiling water, and more rarely katana-watari or climbing up a ladder of swords. All these three feats, when closely examined, will be seen to point to the two characteristically shamanic accomplishments of mastery of fire and the magical flight to heaven." Quoted from: The Catalpa Bow: A Study of Shamanistic Practices in Japan by Carmen Blacker, p. 208.

"Fire-walking, hi watari, is the one feat in the yamabushi's ancient magic repertory which may still be seen practised in many places in Japan, particularly in spring and autumn, at the conclusion of the saitō-goma or magic bonfire rite. The embers of the great conical pyre, the burning of which is a ritual of the greatest beauty and symbolic power but which it would be irrelevant to describe at this point, are raked out by yamabushi with long bamboo rakes to form a red and smouldering path about twenty feet long. A squadron of yamabushi draw up at the head of the path, loudly recite certain mantras, then stride firmly in procession down the smoking cursus. By this action, it is believed, they have so reduced the essence of the fire that it is not only safe but extremely beneficial for all and sundry from the profane world to traverse the path too." (Ibid., p. 223.)

The image to the left was found at Pinterest. |

|

Ho |

帆

ほ

|

Sail crests or mon: "Perhaps the most striking thing about maritime motifs in Japanese design is that they are exceedingly rare." This is what John W. Dower said. But he also added that when there was a net or vessel represented it tended to be something we might notice out of the corner of our eye. Japan was not a maritime state and little emphasis was given this arena. These motifs "...carried comparatively little prestige." Unlike other Japanese terms sailing words seemed to lack the layers of significance and punning found in everything else.

Source and quotes from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 121.

John Dower: ジョン.ヴ.ダワー.

|

|

Hōgu |

法具 ほうぐ |

Ritual implements of Buddhism such as the kongōsho (vajra) and the horin (wheel of the law). |

|

Hōjō-e |

放生会 ほうじょうえ |

The ritual release of animals, especially fish and birds. The first Hachiman hōjō-e was held during the reign of the Emperor Go-Sanjō (1034-73). When the emperor abdicated he became a Buddhist priest.

The hōjō-e was one of the two most sacred ceremonies held annually at the Hachimangū (八幡宮) in Kamakura after 1221 Yoritomo had observed this rite before a statue of Kannon since he was a child. "In Bunji 3 (1187) he instituted the hōjō-e as a large-scale ceremony to be held at the Hachimangū annually on the fifteenth day of the eighth month. As part of the festivities a mounted archery contest was also held at the shrine. ¶ The hōjō-e became the biggest festival in Kamakura, for commoners as well as bushi. It was a combination of Buddhist memorial service and martial festival. At first it was held on one day, the fifteenth of the month. From Kenkyū 1 (1190) it was carried over onto the sixteenth as well. On the fifteenth the shrine was first blessed by the sacred palanquin bearing the divinity. The shogun descended from his horse at the southern entrance, walked across the red bridge into the compound, and visited Wakamiya and Hongū shrines. Gifts of horses were presented to the gods, and the ceremony of releasing birds and fish into the pond, accompanied by the chanting of the Lotus Sūtra, was held." Quoted from: Religion in Japan: Arrows to Heaven and Earth in an essay by Martin Collcutt, pp. 111-12.

Literally 放 means 'to set free', 生 'life' and when 会 is used archaically it means to have a Buddhist ceremony or festivity. |

|

"The hōjō-e and gyōkō-e are the two most important ceremonies celebrated at the Usa Shrine. The hōjō-e, a Buddhist ceremony commemorating the Buddha's prohibition of fishing and hunting, is believed to have been first celebrated in Japan at the Usa Shrine in 720, following an uprising in Hyuga and Osumi provinces in southeastern Kyushu. Nakano sees this Buddhist symbolism as a later overlay on an ancient ritual of renewal, which involved the union of previously autonomous regions. The heart of the yearly hōjō-e is, in fact, the replacement of Hachiman's shintai, a copper mirror made by a priest of the Komiya Hachiman Shrine from metals mined from Mount Kawara, located directly behind the shrine. On completion, the mirror is carried by parishioners from Mount Kawara eastward through Buzen Province to Usa Shrine where it remains until the following year." Quoted from: Shinzō: Hachiman Imagery and its Development by Christine Guth Kanda, p. 37

"The Hōjō-e Ceremony began with dancing, music, and horse riding, and then Buddhist monks released clams and fish into the Hōjō River while others chanted scriptures. Scholars of Japanese religion point out that this popular ritual became an imperial rite when the emperor ordered that the Hōjō-e Ceremony be conducted throughout the country. Records from the Usa Hachiman Shrine and zooarchaeological sites provide additional evidence that monks performed the ceremony at other Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines. As part of state protocol, shogunal officials from the medieval capital of Kamakura abstained from eating fish or meat before visiting shrines." Quoted from: The Lost Wolves of Japan by Brett Walker, p. 64

[The Hōjō-e Ceremony] "consisted of layers of native and imported beliefs that, over time, overlapped and intertwined with one another to form patterns in the complex tapestry of early Japanese religious life." Ibid.

"As Jane Marie Law has suggested in a provocative article on the ideological history of the Hōjōe: 'At the heart of this rite is a deep concern over the violence within the Hachiman cult and the need to make amends and appease the victims. It also demonstrates how a public rite and spectacle ultimately legitimates the violence of dominant authority, even when claiming to appease the victims of the original event itself.' ¶ In sum, the ideological logic of the Hōjōe in its religio-political context performance is twofold: the subjection of military enemies is both legitimized in the name of Hachiman and domesticated through the appeasement of Hachiman's victims. Even as living beings are saved in the ritual performance of the Hōjōe, such a liberation takes place on the basis of a previous subjection of living beings. In effect, the Hōjōe's ritual liberation appeases by means of substitution, metaphorically transforming the victims of military violence into the bodies of fish and birds that are then released into nearby rivers and fields." Quoted from: Theatricalities of Power: The Cultural Politics of Noh by Steven T. Brown, pp. 100-101

"The first precept of Buddhism, reverence to life, resulted in the widespread observance of vegetarianism among the Buddhist community (with some ridicule on the part of Confucianists). It also led to the practice of releasing animals on special occasions known as hojo-e. This ceremony has been practiced for over a thousand years in China and Japan, where it originally entailed delivering animals to nature preserves. It eventually became associated with the demonstration of became associated with the demonstration of political power in medieval Japan..." Quoted from: A Companion to Environmental Philosophy by Dale Jamieson, p. 59

In Miraculous Stories from the Japanese Buddhist Tradition: The Nihon Ryoiki of the Monk Kyokai on page 172 there is the story of a woman who purchases a crab, takes it to a priest and asks him to perform a ceremony (hojo-e) before releasing it.

"The policy of animal protection that had first been declared by the Indian emperor Aśoka spread with Buddhism to China and Japan, where it periodically gained favor as a means of earning merit. The twentieth precept of the Fan-wang-ching (Brahmajāla Sūtra) declares: ¶ If one is a son of Buddha, one must, with a merciful heart, intentionally practice the work of liberating living beings. All men are our fathers, all women are our mothers. All our existences have taken birth from them. ¶ Therefore all living beings of the six gati (animals, humans, gods, titans, demons, hungry ghosts) are our parents, and if we kill them, we will kill our parents and also our former bodies, and all fire and wind are our original substance. ¶ Therefore, you must always practice liberation of living beings (hojo) (since to produce and receive life is the eternal law), and cause others to do so; and if one sees a worldly person kill animals, he must by proper means save and protect them and free them from their misery and danger." Quoted from: Nonviolence to Animals, Earth, and Self in Asian Traditions by Christopher Chapple, pp. 29-30

Later Chapple wrote: "The influence of this and other texts such as the Suvarnaprabhāsa Sūtra caused Chinese and Japanese leaders to declare the institution of hojo-e or 'meeting for liberating living beings.' In the sixth century, the monk Chi-i reportedly convinced more than 1000 fishermen to give up their work. He also purchased 300 miles of land as a protected area where animals could be released. In 759 CE the Chinese Emperor Suh-tsung established 81 ponds where fish could be released; this was followed by similar actions on the part of Emperor Chen-tsung (1017 C.E.)." Ibid. |

||

|

|

||

|

Hōju |

宝珠

ほうじゅ |

The jewel motif: Years ago I studied with an expert in Chinese art. He told me that this was the flaming pearl of wisdom that dragons, adult dragons, were forever chasing. (Baby dragons never chased flaming pearls.)

In Japan the term hōju, which can also be pronounced hōshu, translates as jewel.

See also the entry on yakara no tama. This motif is also known as the hoshi no tama.

This jewel "...is used for the exorcism of evil spirits; it is carved upon the topmost point of pagodas and temples, of shrines and gravestones."

Quoted from: Japanese Art Motives, by Maude Rex Allen, published by A. C. McClurg & co., 1917, p. 161. |

|

In 1906 Katherine Augusta Carl wrote in her With the Empress Dowager of China (published by Eveleigh Nash, p. 284) that after nighttime processions "...a glowing tableaux, a pair of illuminated dragons writhed into the court and struggled for the 'flaming pearl,' which flitted around with elusive fantastic movements, ever beyond their grasp. I was not able to find out the origin of the Imperial legend of the Double Dragon and the Flaming Pearl, representations of which appear everywhere at the Palace on whatever is meant for Imperial use, or for any official function over which the Emperor is supposed to preside. It is on all the thrones of the Dynasty; it adorns the Imperial pennant; it is cut into stone, carved into wood, and painted in pictures. It decorates the gowns of higher officials, and is embroidered upon the Court dresses of the Ladies of the Palace. At the Birthdays of the Emperor and Empress, and at all Dynastic celebrations there are realistic celebrations of the immortal struggle where the Double Dragons strive to absorb the 'flaming pearl.'" Carl believed that this was the eternal conflict between good and evil, but that the flaming pearl would forever remain elusive. I am not convinced of her interpretation. From another book published in 1912 about prominent American women it states that Ms. Carl was inducted into the order of the Double Dragon and Manchu Flaming Pearl by the Empress Dowager.

C.A.S. Williams in his Chinese Symbolism and Art Motifs (published by Castle Books, 1974 edition, p. 138) isn't convinced that it is a pearl the dragon is chasing. "The round red object which seems to be the constant appurtenance of the dragon is variously described as the sun, the moon, the symbol of thunder rolling, the egg emblem of the dual influences of nature, the pearl of potentiality - the loss of which betokens deficient power - of the 'night-shining pearl' (夜明珠) which professor Giles defines as a carbuncle or ruby."

Ernest Ingrsoll in his Dragons and Dragon Lore of 1982 deals head on with the confusion about this object in his chapter called "The Dragon's Precious Pearl". Right off he refers to it as the "...so-called Pearl..." Naga queens who live in underwater palaces wear pearl necklaces. Vedic scriptures talk of a magical jewel once possessed by naga maidens, but lost out of fear of the terrible garuda. But "...in Buddhism... [it is] the jewel in the lotus, the mani of the mystic, ecstatic, formula Om mani padme hum - - 'the jewel that grants all desires,' the divine pearl of the Buddhists throughout the Orient." (p. 71) In Japan and Korea they believed that the chief or yellow dragon carried a pear-shaped pearl on its forehead and that it had supernatural and healing powers. Unlike Williams, above, Ingersoll describes the object as being "...white or bluish with a reddish or golden halo, and usually has an antler-shaped 'flame' rising from its surface." It often has a comma shaped appendage, too. (Ibid.) ¶ "Japanese designers like to form the handles of bells, whether big temple bells or tiny ones, of two dragons affrontes, with the tama [i.e., jewel] between them. One Japanese carving represents a snake-like dragon coiled tightly around a ball, marked with spiral lines, illustrating devotion to the tama." (p. 72) Visser refers to it as 'the pearl of perfection.' (Ibid.) ¶ De Groot describes ascending dragons on a priest's robe belching out balls which probably represent thunder. "...the ball between two dragons is often delineated as a spiral... [denoting] "...the rolling of thunder from which issues a flash of lightning." Ingersoll adds: "In Japanese prints a dragon is frequently accompanied by a huge spiral indicating a thunderstorm caused by him. Are the antler-shaped appendages rising from the 'ball' intended to represent lightning-flames?" (p. 73) Ingersoll also notes that "In the Nihongi... it is related that in the second year of the Emperor Chaui's reign (A.D. 193) the Emperess Jingo-kogo found in the sea 'a jewel which grants all desires,' apparently the same lost by the frightened Naga Maidens." (p. 74)

For examples of the lightening and thunder motifs in Japanese print form go to our page devoted to lightening images. |

||

|

|

||

|

Hōkaburi |

頬被り

ほうかぶリ |

Hand towel tied under the chin like a head kerchief. This term also has a second meaning: feigning ignorance.

The first character is hō (頬) or cheek of the face.

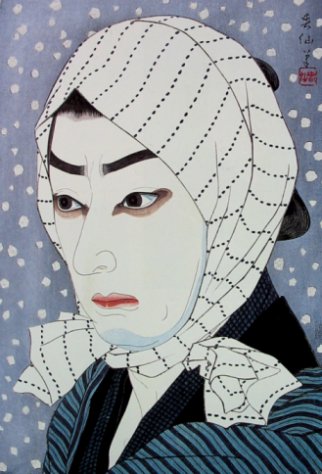

The image to the left is by Natori Shunsen (名取春仙) and the cartoonish one above which is from one of my favorites series of all Japanese prints is by Kuniyoshi. |

|

Hōki |

帚

ほうき

|

Broom: In ancient China the broom came to be identified with insight, wisdom "...and the power to brush away all the dusts of worry and trouble."

"The manifold evil spirits are supposed to be afraid of a broom." de Groot in his Religious System of China (vol. 6, p. 972) states "Many families are in the habit of performing a kind of pretence sweeping with a broom on the last day of the year, rather than intending the removal of evil than that of filth."

Source and quotes from: Chinese Symbolism and Art Motifs, by C.A.S. Williams, Castle Books, 1974 edition, pp. 50-51.

Like the Chinese the Japanese saw the broom as an instrument of expelling evil. However, it has another use too: Placing a broom upside down is a sign to a guest that they have overstayed their visit. [My friends have either put on music they thought I would hate or they would change into their jammies.]

In the West it is walking under a ladder or breaking a mirror, but in Japan the simple act of stepping on or over a broom "...is believed to invite a curse or punishment."

"Hoki has also been used as a charm for a safe and easy child delivery in many parts of the country. It is placed upside down at the foot of the mother-to-be in prayer for successful childbirth, as it sweeps away all evil spirits and sickness."

In some locations the broom is offered a bottle of saké until the child is born. Then it - the broom and not the baby - is taken to a shrine and tied to a tree for three days.

Another superstition borrowed from the Chinese was the belief that a broom could keep the dead from moving about on their own.

Source and quotes: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, the Japanese Times, Inc., 1985 edition, pp. 19-20.

The images to the left are from a print by Yoshitoshi representing Jō and his devoted wife Uba. They represent eternal love and are the subject of one of the Noh plays of Zeami Motokiyo (世阿弥元清).

|

|

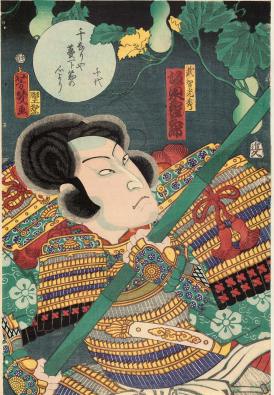

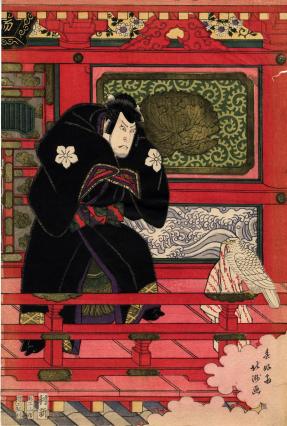

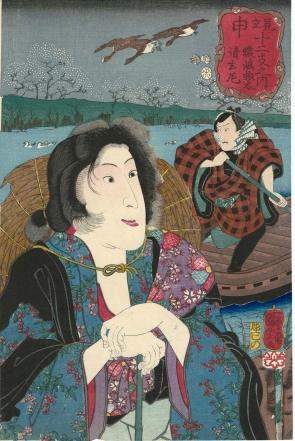

Hokuei |

北英 ほくえい |

Artist fl. 1829-1837 1

Hokushū's main pupil was an artist named Hokuei who worked briefly from the late 1820s to the mid-1830s. Virtually nothing is known of his life beyond his name and address... and a surimono-style portrait of the actor Nakamura Utaemon IV, which was published posthumously in the spring of 1837 as a memorial to the artist with a eulogy from his publisher... Hokuei was worthy of his lineage and produced, often in collaboration with the engraver Kasuke, some of the masterpieces of the Osaka surimono style.... Around 1839 a new range of luminous, saturated colors began to appear in the prints of Hokuei and Shigeharu, which combined with the earlier techniques to lift the surimono style to its apogee. The style ceased abruptly in 1837 in the face of the city's political and economic disturbances. The technique but not the scale of these sumptuous oban was revived successfully in the late 1840s. ¶ After Hokuei's death, Osaka print publication languished.

Quoted from: The Theatrical World of Osaka Prints by Roger Keyes, pp. 29-30.

The image to the left is from the Lyon Collection. Click on it to learn more. |

|

Hokuto shichisei |

北斗七星

ほくとしちせい |

The Big Dipper - "Another legend tells of the Chiba, on the brink of defeat in a 10th century battle. The Big Dipper constellation (北斗七星; hokuto shichisei) shone brightly in the night sky, so the Chiba prayed to Myōken Bosatsu, a Bodhisattva associated with the constellation. In response, they received a vision, and the next day proved victorious. The Chiba referred to this legend with various star-based mon, with either a larger circle or a crescent representing a moon."

To the left is an image of one of the crests or mons used by the Chiba clan. It represents the Big Dipper. |

|

Hōmongi |

訪問着 ほうもんぎ |

There are contradictory sources on the houmongi, but what else is new? Some say that it is a type of kimono worn by married women while others say that being married is not necessarily a requirement. It is either formal or semi-formal and is often worn when making visits or attending weddings. One source says that the brides 'maids' often wear these.

|

|

One distinction does seem to be that this robe generally has an elegant, if understated, continuous flowing design. Very Audrey Hepburnish, but in a Japanese way, of course!

Hōmon 訪問 means 'to visit'. (Like so many specific terms you can find numerous other entries on the Internet if you use alternative, accepted spellings. In this case try 'houmongi'. A suggestion: For those of you who would like to know more or see numerous examples of this type of kimono all you have to do type the entry into Google or cut and paste the kanji or hiragana into the search box. I would suggest doing this even if you don't read Japanese or French or Swahili or Urdu. You will be surprised by what you can pick up simply by looking at more Internet sites. Of course, you have to dig through a lot of c... to find what you want sometimes, but I guarantee it will be worth the effort.

If anyone out there knows anything more specific I would love to hear from you. Also, I would like to find get permission to reproduce an image to illustrate this entry. If you can help there too I would very appreciative. |

||

|

|

||

|

Hōmyō |

法名 ほうみょう |

A posthumous Buddhist name given to the dead. It often appears on memorial or death prints (shini-e) dedicated to actors. It is also referred to as a kaimyō (戒名).

"After the introduction of Buddhism the custom of giving kaimyo, or hōmyo, 'religious names,' to the dead became common. These were inscribed on the ancestral tablets and on the grave-stones, so that rarely were actual personal names to be found in such connexions." By the late 19th to early 20th century this practice was changing to a more Western style with the use of personal given and family names. (Source and quote: Encyclopædia of Religion and Ethics, edited by James Hastings, published by Charles Scribner's Sons, 1917, p. 168)

Another form of posthumous name is the okurina (贈り名) which "...have been common with the royalty and among the nobility. In the reign of Kotoku (645-654) the posthumous name Jimmu was given to the first sovereign, and since that time the custom has continued until the present time, when the late emperor is known by the posthumous name Meiji Tenno. These names have for the most part been characteristic of the individual or his reign or some local associated with him." (Ibid.) |

|

The hōmyō was given by a Buddhist priest right after a person's death. The name was then inscribed on a wooden memorial tablet or ihai (位牌). "From the eighth century it became the almost universal custom to set up boshi 墓誌, or monuments, to mark the position of the grave. These were of all shapes and sizes, and constructed of stone, copper, or other durable material. They bore inscriptions setting forth the name and rank of the deceased; and in some cases words were engraved upon the tablets, eulogistic of the dead. (Source and quote: Transactions of the Asiatic Society of Japan, from "Japanese Funeral Rites", by Arthur Hyde Lay, vol. 19, 1891, p. 525)

William Hare Newell in his book Ancestors (p. 65) gives a lucid description of why there is a birth name and then a separate death name: "Life in this world is growth to full adulthood. Life in the other world is growth to full ancestorhood. Any human being who starts this earthly journey receives a new name at his birth. In the same way, every soul who starts the other journey at his death, a new starting point, also receives a new name. He receives his first name (zokumyō [common name]) when his body leaves his mother's womb and starts an independent existence: this revelation of a 'new power' is consecrated by the new name. He receives his second name (kaimyō [posthumous name]) when his soul leaves his body and starts an independent existence (although like the child , he will be still highly dependent for some time upon the care of others). This new revelation of again a 'new power' is symbolized by a new name."

For more general information see our entry on Japanese names on our J thru Kakuregasa index/glossary page.

"The priest's other major responsibility is giving the deceased a posthumous name (hōmyō in the Jōdoshinshū sect, hōgō in the Nichirenshū sect, and kaimyō in other sects). The posthumous name is written in black calligraphy on the two wooden memorial tablets (shiraki-ihai). One wooden tablet is cremated with the deceased while the other is kept at the domestic Buddhist altar until the 49th-day memorial service. Later the posthumous name is rewritten by the priest in gold ink on a black lacquered memorial tablet (hon-ihai), which is kept on the domestic Buddhist altar (butsudan)." (Quoted from: The Price of Death: The Funeral Industry in Contemporary Japan by Hikaru Suzuki, p. 169) See also our entry on ihai on our Ihai thru Iwai page.

The hōmyō is the dharma name. |

||

|

|

||

|

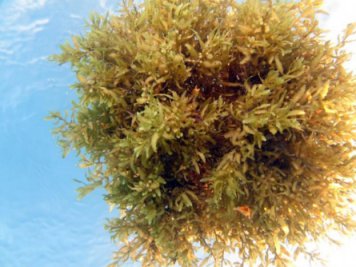

Hondawara |

馬尾藻

ホンダワラ |

Saragossa or gulfweed. A seaweed which dries to a golden color and was used for ornamental New Year's decorations.

Two different sources give two different ideas about the symbolic significance of hondawara. One said it represented wealth. One said happiness. Well, perhaps that is basically really the same thing.

As with so many other biological/botanical terms it is difficult to sort out which plant or organism is actually being referred to. Different sources give different names. Sometimes they are the same, but at other times they are confusing one for the other. In the Commercial Products of the Sea by Peter Lund Simmons hondawara is referred to as Halochloa macrantha. ¶ In the Kojiki presented to the Imperial Court in 712 A.D. it says that the Deity Wondrous-Eight-Spirits was assigned the task of preparing a banquet for the gods. After turning into a cormorant the Deity Wondrous-Eight-Spirits dove to the bottom of the sea to scoop up red earth to make the heavenly platters and to sea-weed stalks. He used the latter to start a fire. In footnote 56 the translator, Basil Hall Chamberlain, said this is "Supposed to be the same as, or similar to, the modern hon-da-hara (Halochloa macrantha)." On 3/25/10 we corrected a mistake we made in the spelling of Halochloa macrantha. Originally we had it as Holochloa. Sorry. Also, the citation is from the 1981 edition, p. 127, note 36.

In an 1889 book by J. J. Rein, The Industries of Japan, it is referred to as houdawara is eaten with vinegar and pickled. (Is this a typo or is it another variation? Don't know.) ¶ Numerous scientific sites say that hondawara is Sargassum fulvellum. ¶ James Curtis Hepburn in his 1886 Japanese-English dictionary gives nanoriso (莫告藻) as a synonym. This is an older term according to Steven D. Carter. ¶ In Useful plants of Japan described and illustrated published in 1895 notes that hondawara should be eaten when young. ¶ In the Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary (1931 edition) hondawara is identified as Saragassum bacciferum. Yeesh! ¶ Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan entry by Kazaki Hideo (vol. 7, p. 46) it is noted that "The 8th century Man'yōshū anthology contains more than 90 poems which mention seaweed." ¶ Two other synonyms are cited in Chado: The Way of Tea (p. 44) are jimba-sō (神馬藻) and tawaramoku (俵藻草). In this book hondawara is listed as hodawara (穗俵), but is definitely the same thing.

The photo to the left shows a ball of floating Saragassum seaweed from the Smithsonian. It was taken by Seabird McKeon. |

|

Honden |

本殿

ほんでん |

In Shinto this is the "...main shrine or inner sanctuary whre the kami is enshrined." Quoted from: A Popular Dictionary of Shinto by Brian Bocking, p. 54.

The image to the left is the honden at Gokōnomiya Shrine (御香宮神社本殿) in Kyoto. The one above is the honden at the Usaka-jinja (鵜坂神社) in Toyama. Both were posted at commons.wikimedia by Nnh. |

|

Hōnoki |

朴の木

ほおのき |

One of several woods used to print woodblocks. Referred to as Magnolia obovata (Thun.) in the West. Often used in modern printmaking for small prints. 1 Click on the highlighted number one to the left to see the masterful use of hōnoki by Kokei.

|

|

Synonymous with M. hypoleuca it can grow as tall as 70 to 100' with a 7' girth with grayish bark. [The height and girth meausrements are all over the place. Just thought you might want to know.] One source says it is also referred to as the Japanese cucumber tree, but I don't know why. That is certainly not consistent with the flower shown above. What is one to think? Several early Western publications say that the flowers are generally purplish. Another source even says the m. obovata is a shrub.

In a publication from 1885 there is a description which differs with the sample shown above - another conundrum which I don't have the expertise to resolve: "The light, greyish white wood changes gradually to a deeper shade. It is soft, easily bent, and elastic, and has a fine even grain, which makes it applicable to many uses. The wood engraver uses it in patterns for cloth printing, and the lacquerer finds it adapted to various small articles." It was used somewhat in basketry. "Sword sheaths (Katana-no-Saya) were also formerly made out of Hô-no-ki. In Niigata and Yonezawa it is used as the groundwork of nearly half of all the lacquer ware, and from it is prepared the soft, fine-grained charcoal which is used throughout the whole of Japan for rubbing the lacquer, and for polishing the enamel of cloisonné ware."

Source and quotes from: The Industries of Japan: Together with an Account of Its Agriculture, Forestry, Arts and Commerce, by J. J. Rein, published by Hodder and Stoughton, 1889, p. 259. [Another source pointed out that it was believed that hōnoki was so soft that it was incapable of scratching Japanese swords. That's why it was chosen for it scabbards - frequently lacquered on the outside.]

It would seem that hōnoki was also used in the process of mirror making, but not for the final reflective surface. Rather for it base made to take the combination of mercury , tin and lead.

Source and quote from: The World of Magnolias, by Dorothy J. Callaway, Timber Press, 1994, 87.

The bark has been used for eons

in both Chinese and Japanese medicines.

Both the photo of the flower and the bark are shown courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. A great site. |

||

|

|

||

|

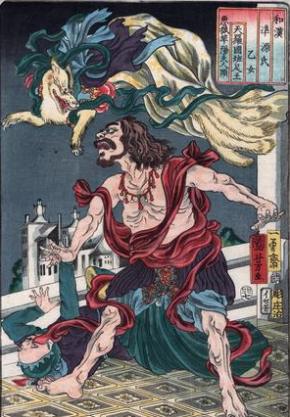

Hō-ō |

鳳凰

ほうおう |

The Phoenix is "...used as a symbol of happiness or good fortune..." Like so many other motifs this has a Chinese origin. Its image "...adorns the roofs of many court and other buildings, as well as the mikoshi or portable shrines carried in procession in shrine festivals."

Quoted from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese (pp. 416-17)

In a reprint from 1893 in a book on Frank Lloyd Wright it says: "The Ho-o is described by the ancients has [sic] having the head of a cock, the beak of a sparrow, the neck like a moving snake, feathers like dragon scales piled one upon the other, the wings of a Kirin (a mythical animal), and a tail like that of a fish. Its plumage is brilliant with all the colors, the whole effect being one of supernatural beauty. Little difference exists between the male and the female. It is said to ascend for nine thousand miles into the heavens. Its song resembles the sound of the Sho (a Chinese musical instrument), the female accompanying the male, when he sings, in notes of marvelous purity.... The bird makes its home in the kiri tree (Paulownia Imperialis), and lives only on the fruit of the bamboo. It is said never to feed upon live insects nor to tread upon live grasses; hence it has become an emblem of holiness and mercy. [¶] The Chinese believed the bird to be a native of Japan. Their natural history mentions it as a bird of the Land of Refinement (Kunshi-Koku), a name given to Japan a thousand years ago. It is further said to make its appearance only when a sovereign is on the throne whose rule is full of love and mercy, free from the destruction of the life of man or the lower animals, and whose people are in the enjoyment of peace and prosperity."

Quoted from: Frank Lloyd Wright and Japan: The Role of Traditional Japanese Art and Architecture in the Work of Frank Lloyd Wright, by Kevin Nute, published by Taylor & Francis, 1993, Appendix C (1893), p. 191. |

|

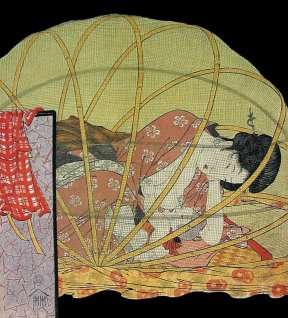

Above is a detail of an

illustration by Utamaro from the 1804 book "Yoshiwara Picture Book of Annual

Events in the Green Houses" painting the image of the phoenix in the whorehouse is Utamaro himself. However, there doesn't seem to be any firm proof of this.

Japanese Art Motives by Maude Rex Allen (published by A. C. McClurg & Co., 1917, pp. 48-9) gives a wholly different description of the the phoenix. "The hō-ō... is found in the earliest wall decorations of China, and was first depicted as an immense eagle carrying large animals in its claws - like the Greek gryphon, the Indian garuda, and the Persian rukh. Later it was endowed with beautiful, colored feathers, and became the feng-hwang of China." Allen added that "The feng-hwang is the essence of fire; it is born in the vermilion cave; it perches only on the kiri; its body is adorned with five colors (symbolizing the five virtues: obedience, uprightness of mind, fidelity, justice, and benevolence); its song contains five notes; it eats only the seed of the bamboo, and drinks only from a sacred spring... [¶] The Chinese mystics believed it to symbolize the entire world: its head is the heaven; its eyes, the sun; its back, the crescent moon; its wings the wind; its feet the earth; its tail the trees and the plants. [¶] The hō-ō is used as an emblem of the empress, as the dragon is an emblem of the emperor. The emperor's carriage is called Ho-ren. In China, brides are allowed to wear a head-dress in the shape of the feng-hwang."

A thought: As I was assembling information about the concept of the phoenix in East Asia I also read about the Western phoenix. These two creatures differ considerably in origin and behavior. The Western phoenix immolates itself only to rise from the ashes to repeat this process over and over again. The feng-hwang/hō-ō doesn't do this, but it reminded me of many of the stories I read about tengu. There are many stories where these bird-like creatures dance themselves into such a frenzy that they burst into flames which consumes then. Then a little later they suddenly reappear to repeat this act. I seriously doubt that there is any connection between the fire prone phoenix and the tengu. What they share in common is the ever creative human mind. ¶ In Christian lore the phoenix is representative of the resurrection of Christ. |

||

|

|

||

|

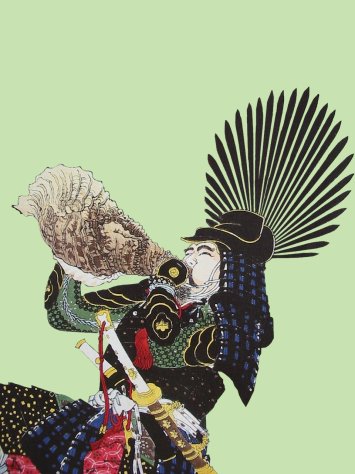

Horagai |

法螺貝

ほらがい |

Conch shell trumpet: Used in India as a military tool prior to the introduction of Buddhism. For that reason it became a symbol of authority. With Buddhism it became "...an icon of spreading the Law.... As such, the conch was counted as one of the eight symbols said to be found on Buddha's footprint." In Japan it was associated with the Senju or 1,000-armed Kannon and was closely linked to the itinerant monks who were known for their esoteric practices. As in ancient India it was adopted as a military signaling device.

Baird also notes that Benkei is often seen in association with the conch shell.

Source and quotes: Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design, by Merrily Baird, Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., 2001, p. 128.

"A horn formed by attaching a simple mouthpiece to the end of a conch shell. Of Indian origin, the instrument diffused along with Buddhism throughout Southeast Asia and East Asia, entering Japan via Korea in the Nara period (710-794). It was employed in Buddhist ceremonies and as one of the religious accoutrements other ascetic Shugendō practitioners. The horagai was also used to sound the signal for advance and retreat in premodern warfare."

Quote and source: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan entry by Misumi Haruo (vol. 3, p. 227)

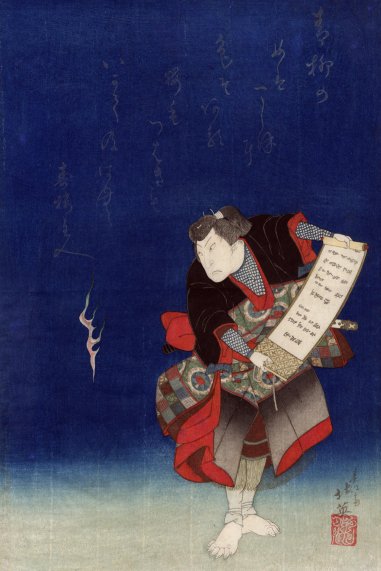

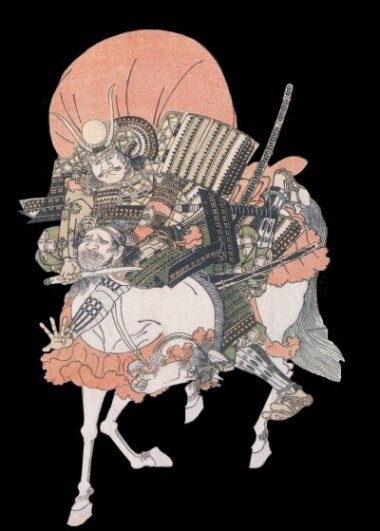

Note that the image to the left is a detail from a print by Yoshitoshi showing Hideyoshi blowing the conch trumpet to let his troops know that it is time to begin the attack at Shizugatake (賤ヶ岳). |

|

In China the conch shell was also a "...one of the insignia of royalty, and the symbol of a prosperous voyage, while it is also regarded as an emblem of the voice of Buddha preaching..." Quote from: Chinese Symbolism and Art Motifs, by C.A.S. Williams, Castle Books, 1974 edition, p. 83.

"Like Buddha's spiral curls... these shells through ages innumerable, and over many lands, were holy things because of the whorls moving from left to right, some mysterious sympathy with the Sun in his daily course through Heaven." Ibid.

The conch-shell trumpet is often mounted with bronze or silver. They were "...also used as fog-horns by fishing boats..." Ibid.

The conch shell was applied or worn, but only rarely, by some military figures as their family crest or mon because of the shell's use in warfare. Source: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 27

Since the conch was also a tool of Buddhism and especially mountain ascetics "...it was ascribed magical qualities in dispelling sins, demons and enemies." (Ibid., p. 98) |

||

|

|

||

|

Hōrai |

蓬莱 ほうらい |

The Land of Eternal Youth. In China it is called P'eng Lai. |

|

Hori |

彫

ほり |

Carver "Usually the artist himself did not keep an eye upon all the stages of the printing process and allowed printers and carvers to experiment, which sometimes resulted in new technical achievements. It took about four years to become a skilled printer and at least twice as much before a carver could call himself a specialist. When he reached a high level he put his qualities at the service of the best artists and publishing houses."

Quote from: Ōsaka Kagami, by Jan van Doesburg, published by Huys den Esch, 1985, p. 6. |

|

"Many designers in the history of ukiyo-e were amateur artists, but the engravers were skilled professional craftsmen who underwent a long period of apprenticeship and training before they became masters and were allowed to engrave heads, faces, and major outlines of the figures in prints."

There were so many different carving styles that prints by one artist carved by various engravers often looked like prints by different people. "Some print designers were aware of this issue, although they rarely seem to have had much choice of their engravers." That is why Hokusai wrote one of his publishers requesting that he use a carver named Egawa Tomekichi who he "...could trust to engrave the faces in his pictures the way they were drawn..." and not end up looking like so many other Utagawa heads.

Source and quote: Japanese Woodblock Prints: The Ainsworth Collection, by Roger Keyes, 1984, p. 104.

"...it is certain that some engraving was undertaken by families who worked in their own ateliers and contracted with individual publishers, these engravers often being among the most skilful..."

Less skilled carvers often lived with the publishers and were merely house employees. "Volker has cited one or two instances where the engraver and publisher are the smae person and this may have been more common than is at present believed but the evidence is very scanty." Some carvers were sued for publishing on their own.

Engravers did not just 'copy' slavishly, but often improvised or changed features or elements. The artists did not have direct contact with the carvers and had to convey their wishes through the publishers.

"...it took four years to be an artist, three years apprenticeship to be a printer but ten years to be a first class engraver."

Source and quotes from: The Prints of Japan, by Frank A. Turk, Arco Publications, 1966, pp. 59-60.

"Anecdotes by contemporary blockcarvers about 'the old days' suggest that under the master-apprentice family workshop system, a youngster would start his training to be a nishiki-e blockcarver by cutting lettering. He then moved up to written characters of the prompt books used by the chanters in Kabuki or puppet theaters. From there he learned to remove the excess areas of the color woodblocks... Finally he practiced cutting the outlines for less important parts like the costumes, hands and feet. After more practice only one of the most talented would come to carve facial outlines, until finally he could try the finest carving needed for the elaborate hair-styles of the finishing block." By the end of World War II a carver would have to be 40 to 50 years old before he could tackle the most difficult carving assignments.

Source and quotes: Color Woodblock Printing: The Traditional Method of Ukiyo-e, by Margaret Miller Kanada, Shufunotomo Co., Ltd., 1989, p. 29.

"In Japan the engraver has no honour; he is a mere artisan." This was published by a Westerner, Captain Frank Brinkley (Japan: Its History Arts and Literature, published by T.C. & E. C. Jack, vol. 7, 1904, p. 51 - 1908 edition). This view is not surprising considering how little we know about prominent carvers and how seldom they are credited on individual prints. |

||

|

|

||

|

Hori Asa |

彫朝

ほり.あさ |

Asahisa Ryūtarō carver's identifying seal. We know that this seal appears on a Chikanobu print from 1890 published by Hasegawa Tsunejirō.

carved by Hori Asa in 1890. |

|

Hori Chō |

彫長

ほり.ちょう |

Carver's identifying seal. 1, 2

We know that this carver, Katada Chojirō (片田彫長), engraved blocks for prints bearing the names of Toyokuni III, Kunisada II, Kunichika and Chikanobu.

Active as early as 1861 to as late as 1881.

He carved for Etsu Ka,

Hayashiya Shōgorō in 1863, Sanoya Tomigorō, Wakasaya Jingorō, Tsujiokaya Bunsuke,

Izutsuya, Enshūya Hikobei, Daikokuya Kichinotsuke (?), Daikokuya

Kinzaburō (?), Tsunoi, Hanabukiya Bunzō (?) and 村山源兵衛 (as yet untranslated)

and several others who have yet to be identified.

In 1864 he carved a Kunichika

triptych for Ōmiya Kyūjirō and

a Yoshitoshi in 1867. And on an 1864 print by

Yoshitoshi published by Kakumotoya Kinjirō.

Horikō Chō worked on Kunichika prints for Kikuya Ichibei in 1867; Hori Chō

worked for Yamamotoya Heikichi on Sadahide and Kunisada II prints in 1864

and Yoshitoshi in 1865; on Yoshitora for Shimizuya Naojirō

in 1866; for Maruya Tetsujirō on Kunisada II prints in 1865; on

Toyokuni III in 1861 for Izutsuya Shōkichi;

He also worked for Iseya Tokichi in 1865.

Note: One of the things which has always puzzled me is the role of the master carver in the creation of ukiyo prints. So, I started a search on this particular carver and found a range of dates when his name appeared on the finished prints, a few of the publishing houses he worked for or with and the names of four of the artists he is known to have helped produce.

The Boston Museum of Fine Arts list Katada Chojirō as a publisher from 1888-1904 on prints by Yasuji, Toshimitsu, Shōgetsu, Kuniteru III, Kokunimasa and Rosetsu. So far we have been unable to verify this information. |

|

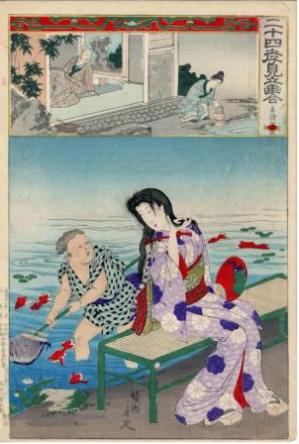

Hori Chōsen |

ホリ朝仙 or 彫朝仙

ほりちょうせん

|

Carver's seals. This carver's seals may only have appeared on some of Kuniyoshi's series Sixty-nine Stations of the Kisokaidō Road from 1853 published by Minatoya Kohei and Takada-ya Tokezō.

The two images above are basically the same thing. But the one on the right is so dark it is nearly impossible to read. That is why we have doctored it in such a way as to make the kanji a little more accessible.

The seal and the image to the left have the alternate seal: ホリ朝仙. |

|

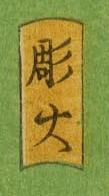

Hori Dai |

彫大

ほりだい

|

Carver whose work appeared from 1861 to 1865. His name was Matsushima Daijirō (松嶋大次郎). He worked on the prints of these artists: Toyokuni III, Yoshiiku, Kunihisa II, Kunichika, Yoshiharu, Yoshitora, Kunitsuna, Kunisada II and Kyōsai. He worked for these publishers: Enshuya Hikobei in 1863, Surugaya Sakujirō, Kameya Iwakichi, Iseya Kanekichi, Ebiya Rinnosuke, Fujiokaya Keijirō, Yamaguchiya Tobei, Koshmuraya Heisuke, Maruya Tetsujirō, Katoya Iwazo, Ōmiya Kyūjirō in 1863 and Sanoya Tomigorō.

Toyokuni III print from 1861 carved by Hori Dai. British Museum |

|

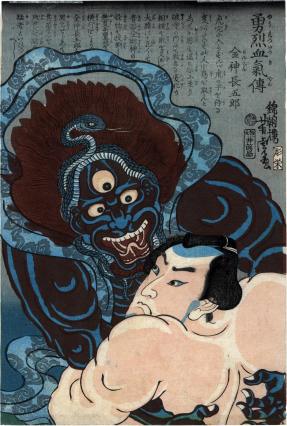

Hori Ei (also Hori Eikō) |

彫栄

ほりえい

|

The carver Watanabe Eizō (1833-1901: 渡辺栄蔵). His seal appears on works composed by Kunichika and Yoshitora. Among the publishers who worked with him were Kiya Sōjirō, Tsujiya Yasubei, Hironoya Shinzō and Fukuda Kumajirō. Hori Ei carved Kunichika prints in 1898 for Fukuda Hatsujirō. He carved Kunichika prints in 1867 for Kikuya Ichibei; for Yamamotoya Heikichi on Kunichika in 1866; for Kagaya Kichibei on Kuniteru II in 1867; for Izutsuya Shōkichi on a Kunichika in 1865.

The image shown above is by Yoshitora and date from 1866. It is from the Lyon Collection. |

|

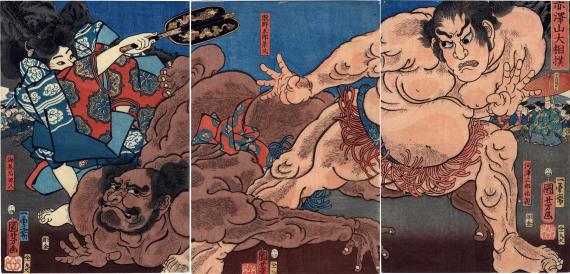

Hori Kane |

彫金

ほりうきん |

Carver's seal for Koizumi Kanegorō. He worked for Nishimuraya Yohachi on Sadahide prints in 1860. He carved Kunihisa II in 1860 and Yoshiiku prints for Kagiya Shōbei in 1861; for Yamaguchiya Tōbei on Kuniyoshi prints in 1855; for Fujiokaya Keijirō on Yoshitoshi print in 1867; for Kiya Sōjirō on Yoshifusa prints in 1859 and Toyokuni III in 1860; for Tsujiokaya Bunsuke on Yoshitsuya prints in 1858; on Kunisada II for Maruya Tetsujirō in 1863; on Toyokuni III in 1860 and on Kunisada II for Kikuya Ichibei in 1863.

The image shown above comes from the Lyon Collection. Click on it to get a better view. |

|

Hori Ken (or more probably Hori Kane) |

彫兼

ほり.けん (or ほりうきん?) |

Carver's seal for Koizumi Kanegorō. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston says that this seal should represent Hori Kane.

Horikō Kane

This carver worked for Kiya Sōjirō in 1860. |

|

Horikō Fusajirō |

彫工房次郎

ほりこふさじろう |

Carver's seal for Matsushima Fusajirō (松島房次郎) also known as Hori Fusa. He worked on Kuniyoshi prints in the mid-1840s for Ibaya Kyūbei; for Iseya Ichibei on Kuniyoshi prints at the same time; for Jōshūya Kinzō on Kuniyoshi prints in 1845; on Kuniyoshi prints for Ibaya Senzaburō in the mid to late 1840s; on Hiroshige prints in mid to late 1840s; on Hiroshige prints for Wakasaya Yoichi in the mid-1840s; for Hayashiya Shōgorō on Toyokuni III prints in the mid-1840s; on Kuniyoshi prints for Fujiokaya Hikotarō in the mid-1840s; for Murataya Ichigorō on Kuniyoshi prints in the mid-1840s.

The image to the left and above come from a Toyokuni III print in the collection of Mike Lyon. The publisher is Iseya Ichibei. |

|

Horikō Gin |

彫工銀

ほりこうぎん |

Carver's seal Asai Ginjirō. Active from at least 1875 to 1890. As best we can tell this carver worked on prints by Yoshitoshi in 1874-75, Yoshitora in 1875, Kunichika in 1875 to 1879 and in 1884 and ca. 1887, Chikanobu in 1878 and 1885 and 1888, Kunihisa II in 1883, Chikashige in 1881, Kuniaki in 1883, Kunisada III in 1890, Hiroshige III in 1882 and Kyosai in 1875. His work appears on prints published by Matsuki Heikichi (松木平吉), Sawamuraya Seikichi (沢村屋清吉), Yoshida Kiyomatsu (吉田喜代松), Tsutaya Kichizō, Ebisuya Shōshichi, Tsujiokaya Bunsuke, Ishii Rokunosuke (石井六之助), Emoto Nao (江本なお), Yamamura Kōjirō (山村鉱次郎), Hara Taneaki (原胤昭), Kiya Sōjirō, Yorozuya Shirobei (万屋四郎兵衛), Yorozuya Magobei (万屋孫兵衛), Matsushita Heibei, Takekawa Unokichi (武川卯之吉), Enomoto Tobei and Sakurai Yasubei (桜井安兵衛).

A different seal by this carver reading Hori Gin appears below. It can be found on a print by Kyosai which we have posted next to it.

|

|

Horikō Hidekatsu |

彫秀勝

ほりひでかつ |

Carver's seal for Ōta Hidekatsu. This carver worked on a Kunichika print for Morimoto Junzaburō in 1876; for Yorozuya Magobei on a Kunichika triptych in the 1860s and on a Yoshitoshi triptych in 1874 and another print in 1876; for Kagaya Katsugorō on a Yoshitoshi in 1873 and Toyokuni IV triptych in 1874.

The 1872 Kunichika image below and the detail to the left are from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

|

|

Horikō Ko-kin |

彫工小金

ほりこうこきん |

Carver's seal. Active in between 1860 and 1863. He worked on prints designed by Toyokuni III and Kunisada II. He worked for/with the publishers Shimizuya Naojirō, Yorozuya Zentarō and Iseya Kanekichi. |

|

Hori Koma |

彫駒

ほりこま |

Carver's seal. This person, his name was Ōta Komachi, worked for these publishers: Kakumotoya Kinjirō in 1854; Ōmiya Kyūjirō in 1862, Echizenya Kajū in 1862; Kiya Sōjirō in 1860; and Kogiya Shobei in 1863; for Shimizuya Naojirō in 1863; Sagamiya Tōkichi (aka Aito) in 1860; for Kogaya Katsugoro in 1865. The artists whose works were carved by him include Kuniyoshi, Fusatane, Yoshiiku, Kuniaki II, Kunichika and Toyokuni III. This seal appears on prints as early as 1854 to as late as 1865.

Above is the 1860 Fusatane print that the seal to the left belongs to. |

|

Horikō Masu? |

ほりこう ? |

Carver's seal. We are not sure of this attribution. If we find out if it is correct we will correct this later. 1 |

|

Horikō Masukichi, also Hori Masu |

彫工舛吉

ほりこうますきち |

Carver's seal. We know that this carver worked on a Kunichika triptych published by Tsujioka Kamekichi in 1867 and 1868. The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston says that this man's name was Ōta Masukichi. He also worked on Toyokuni III print of Nakamura Fukusuke I for the publisher Ōtaya Takichi in 1858; for Gosukuya Kahei in 1869; for Masudaya Ginjiro in 1867; and for Masadaya Heikichi in 1869. |

|

Horikō Shige |

彫工繁

ほりこうしげ

|

Carver who worked on the Yoshiiku print seen to the left. It was published by Ōmiya Kyūjirō in 1865. He also worked on Kuniteru II prints for Daikokuya Heikichi in 1866. |

|

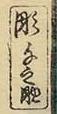

Horikō Shinchō |

彫工深長

ほりこう.しんちょう

|

Carver's seal. He worked on prints by Toyokuni III in 1860 for the publisher Iseya Shōnosuke and again in 1861 for Izutsuya Shōkichi. He also worked for Izutsuya in 1863 on prints designed by Kunichika. Below is a print from the Lyon Collection carved by this man.

|

|

Horikō Tashichi |

彫工多七

ちょうこう.たしち |

Carver's seal for Ōta Komakichi. Also sealed as Hori Tashichi. (See Hori Ōta Tashichi below and Hori Koma above.)

We know this carver worked on prints by Kunichika for the publisher Hiranoya Shinzō. |

|

Horikō Yamaichi |

彫工山市

ちょうこう.やまいち |

We have only found two prints to which this carver contributed. Both date from 1822 and are by Hokushū. Both were published by Toshikuraya Shinbei.

|

|

Hori Masa |

彫政

ほりまさ |

Matsushima Masakichi (松島彫政) - also know under the name Horikō Masa.

Publishers he worked for were Daikokuya Heikichi in 1863, Ebisuya Shōshichi in 1860, Ebiya Rinnosuke in 1859-60 and 1861-66, Enshūya Hikobei in 1861-62 and 1865, Hayashiya Shōgorō in 1860, Hiranoya Shinzō in 1862-63, Horikoshi in 1860, Iseya Kanekichi in 1861 and 1863, Izutsuya Shōkichi in 1861, Kagaya Kichiemon in 1861-2, Kagiya Shōbei in 1863, Katōya Iwazō in 1863, Koshimura Heisuke in 1863, Maruya Jinpachi in 1861, Moriya Jihei in 1865, Ōmiya Kiyūjirō in 1859, 1863-64 and 1866, Sanoya Tomigorō in 1859 and 1865, Sasaya Matabei in 1860, Seibundō Masakichi in 1865, Surugaya Sakujirō in 1863 and Yamamotoya Heikichi in 1859.

collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Artists whose works were carved by this man were Yoshitsuya in 1860, Toyokuni III in 1861-62, Yoshiiku in 1859 and 1863, Isai in 1863, Settei in 1863, Kiyokuni in 1863, Kyōsai in 1863, Hiroshige II in 1863, Kunichika in 1864-66, Yoshitsuya in 1864, Kunisada II in 1865, Yoshitora in 1862-63 and 1865, Yoshiharu in 1865, Yoshikane in 1866 and Yoshitoshi in 1865-66. |

|

Hori Mino |

彫巳の

ほりみの

|

The carver Koizumi Minokichi worked on the Kuniyoshi print to the left, dating from 1852. No publisher seal appears on that print. He also worked for Sasaya Matabei in 1860. Enshuya Hikobei in 1854. Iseya Bunshichi in 1851. Kakumotoya Kinjirō in 1851-52. Moriya Jihei in 1861 and 1865. Izuya Sankichi in 1851. Yamamotoya Heikichi in 1852 and 1857. Shimizuya Tsunejirō in 1852. Maruya Tokuzō in 1867, Kagaya Kichiemon in 1861 and 1863-4 and 1871. Izutsuya Shōkichi in 1852 and 1863. Sumiyoshiya Masagorō in 1852. Kiyo Sōjirō in 1863-65. Iseya Kanekichi in 1852. Kikuya Ichibei in 1865. Fujiokaya Keijirō in 1852 and 1856. Sakurai Yasubei in 1865. Kataoya Seibei in 1863. Tsujiokaya Bunsuke in 1852. Ebisuya Shōshichi in 1853-4. Ōmiya Kyūjirō in 1860. Jōshūya Jūzō in 1850 and 1853. Ebiya Rinnosuke in 1860. Iseya Tōkichi in 1863. Hori Mino worked on Kunichika prints in 1865 for Kikuya Ichibei.

Other artist's works carved by this man include Hiroshige in 1852, Kuniyoshi in 1851-52, Kunichika in 1863-65 and 1871, Toyokuni III in 1850 and 1852-54 and 1860-61, Fusatane in 1865, Sadahide in 1865, Kunisada II in 1864-65 and Yoshiiku in 1861 and 1863-64 and 1867. |

|

Horimono |

彫物

ほりもの

|

A term for tattoo which is also called irezumi.

To the left (top) is a detail from a print by Kuniyoshi. It represents Kyūmonryū Shishin from the Suikoden series. Below is a clearer detail of a dragon's head and claws.

We have 3 pages devoted to tattoos. Below are direct links to those page.

BAD BOYS AND THEIR TATTOOS - page 1

BAD BOYS AND THEIR TATTOOS - page 2 (This page has been removed.)

BAD BOYS AND THEIR TATTOOS - page 3

|

|

Hōrin |

宝輪 ほうりん |

One of the symbols used by Mikkyō (密教) or esoteric Buddhism it represents the wheel of the law. The wheel stands for the continuance of existence through birth, death, rebirth, death, rebirth, death ad nauseum. Only the attainment of enlightenment ends the cycle. The kongōsho or vajra is another of the symbols. |

|

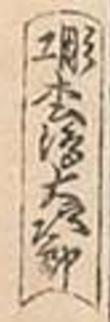

Hori Ōta Tashichi |

彫太田多七

ほり.おおた.たしち |

This is one of the carver's seal for Ōta Komakichi. We know he was active using this seal as early as 1862 and as late as 1866. He worked on prints by Toyokuni III, Kunisada II, Kunichika, Kyōsai, Sadahide, Kiyokuni, Isai, Settei, Yoshikata, Yoshitoshi, Yoshiiku, Yoshimori, Yoshitora and Kunichika. He also worked for/with the publishers Hiranoya Shinzō, Koshimuraya Heisuke, Kagiya Shōbei, Katōya Iwazō, Kogaya Katsugorō, Hayashiya Shōgorō, Gusokuya Kahei, Moriya Jihei, Ōmiya Kyūjirō, Ōtaya Takichi, Enshūya Hikobei and Kagiya Shōbei. |

|

Hori Renkichi |

彫廉吉

ほりれんきち |

This carver, Sugawa Renkichi (須川廉吉), may only have worked mainly on Kuniyoshi prints by Ibaya Kyūbei in the mid- 1840s. One of Hori Renkichi's seal also appears on a Kunisada print published by Wakasaya Yoichi around the same time. A Renkichi seal also appears on a Kuniyoshi triptych with a seal by an unidentified publisher which is listed by Marks as U015 which he calls Chikasuke.

The seal to the left comes

from this Kuniyoshi print |

|

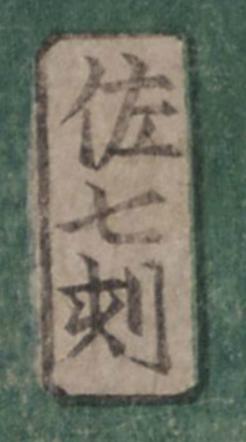

Hori Sashichikoku |

彫佐七刻

ほりさしちこく |

Carver who was active as early as 1851 or earlier because his seal appears on a Toyokuni III triptych published by Yamaguchiya Tōbei that year. A year later on a Kuniyoshi diptych published by Jōshūya Kinzō. In 1855 he worked on Toyokuni III prints published by Kamaya Kihei and Honmo in 1856 on Kuniyoshi prints. In 1864 this seal appears on a Yoshiiku prints published by Ōmiya Kyūjirō. He also worked for Kagaya Kichiemon in 1855 and Tsujiokaya Bunsuke the same year. He worked for Kiya Sōjirō and Fujiokaya Keijirō in 1855. Hori Sashichi carved Yoshitora for Daikokuya Kinnosuke in 1866. prints in 1866. |

|

Hori Sennosuke |

彫千之助

ほりせんのすけ |

Carver Sugawa (須川) Sennosuke, aka Hori Sen, who worked for Sumiyoshya Masagorō and Kobayashi Tetsujirō in 1852 and Koshimuraya Heisuke and Fukuchū in 1853. Jōshuya Kinzō in 1858. Kagiya Shōbei in 1862. Surugaya Sakujirō in 1863. Sagamiya Tōkichi (aka Aito) in 1855, 1856, 1858, 1859, 1860, 1861 and 1862. Iseya Rihei in 1866. Wakasaya Yoichi in 1858. Ebisuya Shochichi in 1858. He carved a Toyokuni diptych for Aritaya Seiemon in 1855. He worked on Kuniyoshi prints for Yawataya Sakujirō in 1852 and a Yoshimori in 1861. He carved Toyokuni III for Kagiya Shōbei in 1862.

Artists whose worked he carved were Hiroshige, Kyōsai, Shunpūsha, Kunichika, Toyokuni III, Kunisada II and Kuniyoshi.

An alternate carver's seal can be seen below. It appears on a Hiroshige print from 1853 and is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

|

|

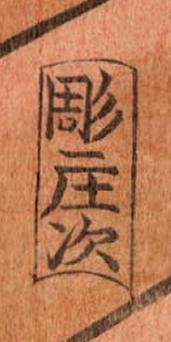

Hori Shōji |

彫庄次

ほり.しょうじ

|

Carver's seal. Known to have worked for the publisher Mikawaya Tetsugorō on a triptych by Toyokuni III in 1852. In 1859 Hori Shōji carved a Yoshitora woodblock for Itoya Fukujirō; a Yoshikazu for Aritaya Seiemon in 1855; a Hiroshige for Maruya Jinpachi in 1854 and also Toyokuni III for the same publisher in the same year and in 1856; a Kuniteru I for Jōshūya Jūzō in 1855; a Kuniyoshi print in 1852 for Jōshūya Jūzō; a Kuniyoshi for Izutsuya Shōkichi in 1855.

This carver also worked on prints published by Yawataya Sakujirō in 1852, Tsutaya Kichizō in 1853 and Kakumotoya Kinjirō in the same year, Iseya Yoshi in 1855 and Tsujiya Yasubei in 1855- 1858. And carved works by Kuniyoshi. He carved a Toyokuni III diptych for Kagaya Yasubei in 1852; and Maruya Tetsujiro on Yoshitora in 1859.

His name was Tsuge Shōjirō. The Kuniyoshi print shown above was carved by Hori Shōji for Iseyoshi.

We added a second carver's seal. See below on the left. This appears on a Kunisada II triptych published by Tsutaya Kichizō in 1851 and other works by them in 1852. |

|

Hori Take |

彫竹

ほり.たけ

|

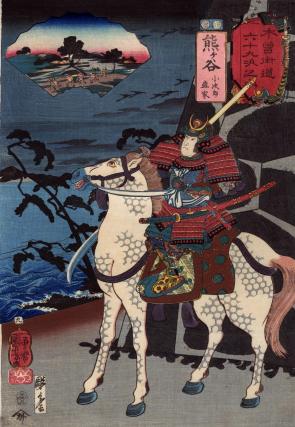

Carver's seal for Yokegawa Takejirō (横川彫武) often seen on late Toyokuni III prints. 1, 2