|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

Bo thru Da |

|

|

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Bōkan, Bokashi, Bokusen, Bonbori, Bon no kubo, Boshi-e, Botan, British Museum, Buckwheat flowers, Buddha's Birthday, Dominique Buisson, Bukan, Bunraku, Busshukan, Butsudan, Butsuzō zui, Camel, Chanoyu, Cha-soba, Chaya-zome, Chigaidana, Chihaya, Chikurin, Chikushōdō, Chi no ike jigoku, Chinowa, Edoardo Chiossone, Chirimen, Chō, Chōai, Chōbunsai Eishi, Chōchin, Chōkei-sō, Chōki-bune, Chōshi, Chronicle of the Battle of Ichinotani, Chrysanthemum (Kiku), Chūban, Chūnori, Chūshingura, Timothy Clark, Dachō, Dadaiko, Daigane, Daikoku, Daikon, Daimyō, Daimyō gyōretsu, Dai-Nippon Rokujuyo-shu no Uchi, Daitoku-ji, Dango, Dannoura no Tatakai (The Battle of Dannoura), Danshichi Kurobei, Daruma, Date, Datehyōgo, Date kurabe okuni kabuki, Date-sagari, Datsue-ba, Dayflower (Tsuyukusa)

亡魂, 暈し, 雪洞, 盆の窪, 母子絵, 牡丹, 大英博物館, 蕎麦, 灌仏会, 文楽, 仏手柑, 武鑑, 仏壇, 仏像図彙, 単峰駱駝, 茶の湯, 茶蕎麦, 茶屋染, 違い棚, 千早, 竹林, 畜生道, 血池地獄, 茅の輪, 縮緬, 蝶, 丁合, 鳥文斉栄之, 提燈 / 提灯, 頂髻相, 猪牙船, 銚子, , 銚子, 菊, 中判, 宙乗り, 忠臣蔵, 鴕鳥, 大太鼓, 台金, 大根, 大根紋, 大黒, 大名, 大名行列, 大日本六十余州内, 大徳寺, 団子, 壇ノ浦の戦, 団七力郎兵衛, 達磨, 伊, 伊達兵庫, 伊達競阿國劇場, 伊達下がり, 奪衣婆, 露草 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Bōkan |

亡魂

ぼうこん |

A departed soul or spirit, sometimes referred to as a ghost. Yūrei is another term for a spirit or ghost.

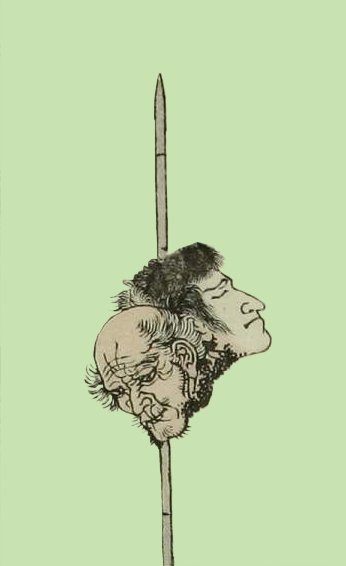

The Kuniyoshi image to the left of Hōkaibō as a bōkan. |

|

暈し ぼかし |

Shading or gradation (cf. ita-bokashi) - While we are mainly concerned with bokashi in the tradition of woodblock printing, bokashi can also be referenced in the arts of weaving and lacquer work. |

|

|

"Beside the printing of flat masses of colour, one of the great resources of block printing is in the power of delicate gradation in printing. The simplest way of making a gradation from strong to pale colour is to dip one corner of a broad brush into the colour and the other corner into water so that the water just runs into the colour: then, by squeezing the whole width of the brush broadly between the thumb and forefinger so that most of the water is squeezed out, the brush is left charged with a tint gradated from side to side. The brush is then dipped lightly into paste along its whole edge, and brushed a few times to and fro across the block where the gradation is needed. It is easy in this way to print a very delicately gradated tint from full colour to white. If the pale edge of the tint is to disappear, the block should be moistened along the surface with a sponge where the colour is to cease. ¶ A soft edge may be given to a tint with a brush ordinarily charged if the block is moistened with a clean sponge at the part where the tint is to cease. This effect is often seen at the top of the sky in a Japanese landscape print where a dark blue band of colour is printed with a soft edge suddenly gradated to white, or sometimes the plumage of birds is printed with sudden gradations. In fact, the method may be developed in all kinds of ways. Often it is an advantage to print a gradation and then a flat tone over the gradation in a second printing." Quoted from: Wood-block Printing by F. Morley Fletcher, 1916

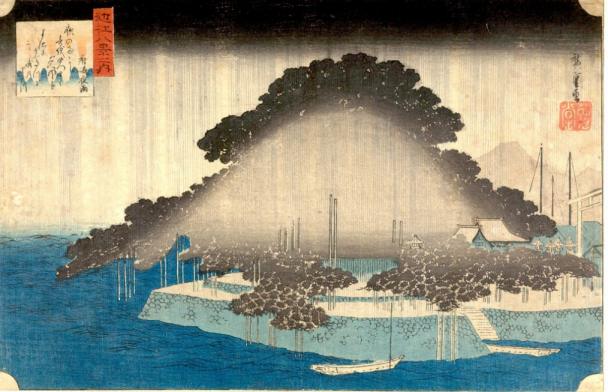

Below is a wonderful example of this technique in Hiroshige's 'Night Rain at Karasaki'. Havard Museums

Matthi Forrer wrote that Toriyama Sekien (1712-1788) was the first to use bokashi in 1774 in Sekien gafu. |

||

|

|

||

|

Bokusen |

卜占 or 卜筮 ぼくぜい |

Divination: "A Taoist-style Bureau of Divination (Onmyō-ryō) formed part of the Imperial Court in the Heian period. Divination to assist harvest and cultivation still forms a part of many festivals. Methods used include futomani, heating the shoulder-blade of a deer and reading the cracks; the popular o-mikuji (divination by drawing lots and numbered slips of paper); archery (o-bisha, mato-i, yabusame, o-mato-shinji) where divination is based on the angle of the arrow in the target, smearing rice-paste on a pole and seeing how it sticks, and sounding a small drum. In the Awaji-shima Izanagi-jingū a form of divination called mi-kayu-ura uses hollow bamboos dipped by farmers in boiling rice to foretell the planting and harvest, while at the Koshiō jinja, Akita, rice paste is smeared on a three-metre pole and divination of the crops is based on the way it sticks. Similar but more complex forms of divination are used in the Kasuga-taisha to determine different planting times for 54 different vegetables." Quoted from: A Popular Dictionary of Shinto by Brian Bocking, pp. 11-12. [See our entry on yabusame.] |

|

Bonbori |

雪洞 ぼんぼり |

Paper covered lamp or lantern - Mark Spahn and Wolfgang Hadamitzky in The Kanji Dictionary (8d3.2) define bonbori as a handlamp or lampstand. The first character 雪 means 'snow'. The second kanji character 洞 means den, cave or grotto. Kozuko Koizumi notes that bonbori have shades. |

|

Bon no kubo |

盆の窪

ぼんのくぼ

|

Nape at the hollow of the neck: A baby's head was shaved, but if a small tuft of hair was left growing at the nape it too was known as bon no kubo.

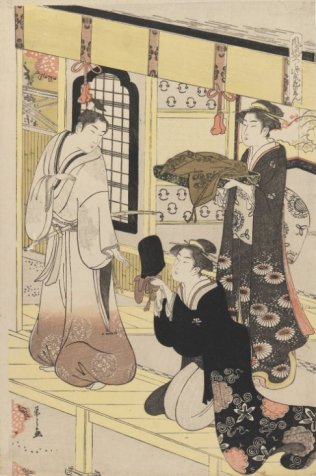

To the left are two details from prints by Kunisada. Notice the subtle indications of the areas at the back of the the head at the nape where the hair has been allowed to grow.

|

|

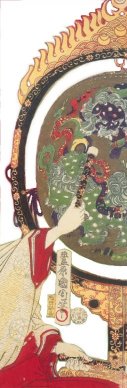

Boshi-e |

母子絵

ぼしえ |

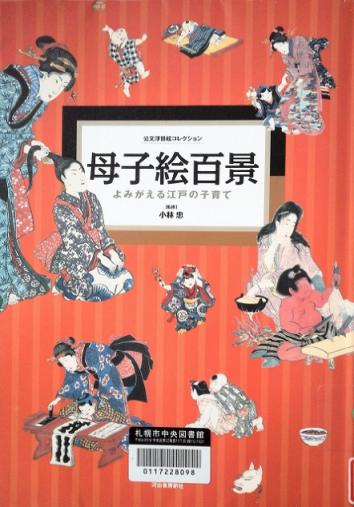

A little known sub-genre of Japanese art. Literally it means "a mother and child" painting or print. But by extension, it has come to include any woman attendant to a child, either a relative, friend or servant.

To the left is the cover of an exhibition of 100 examples of mother and child images. |

|

Botan |

牡丹

ぼたん

|

Tree peony motif: Dower refers to this plant as "the sovereign of the flowers". Previously I had read that it was "the king of flowers" and "the queen of flowers". Eventually I finally found an explanation for this gender confusion, but for the sake of me I can't remember where.

Brought to Japan from China it was valued for its beauty and medicinal properties. In time its use as a family crest "...ranked [it] almost as high as the chrysanthemum, paulownia and hollyhock in prestige."

Source: The Elements of Japanese Design by John Dower (p. 70)

|

|

British Museum |

大英博物館

だいえいはくぶつかん |

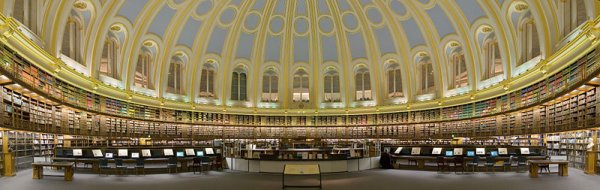

Note that the British Museum is referred to as "daieihakubutsukan" in the kanji and kana to the left. We have added this entry because among other the British Museum owns prints by Kokei. Click on the #1 to see our entry on that artist.

One of the great things I discovered recently is that many of the images posted by contributors to http://commons.wikimedia.org/ have been placed in the public domain. This makes it possible for to post images which would otherwise be covered by copyright exclusivity. What a boon! This particular image was posted by Stormnight. We are grateful for this person's generosity.

Above is a picture, a breathtaking picture of the reading room. While it has little to no direct connection with Japanese prints it is so stupendous I couldn't let it go unpublished thanks to the generosity of the photographer, Dilliff. Bravo Dilliff!

The image to the left is by Andrew Dunn. He has also posted it at wikimedia.org and offered it for general use. Thanks to Andrew too.

The British Museum has a large and impressive collection of ukiyo prints. Here is a partial list of some of the artists in basically chronological order: Kiyonobu, Kiyomasu, Masanobu, Harunobu, Toyonobu, Koryūsai, Bunchō, Shunman, Shunshō, Shigemasa, Toyoharu, Shun'ei, Shunchō, Kiyonaga, Utamaro, Chōki, Eishi, Eishō, Eiri, Eisui, Sharaku, Toyokuni I, Toyohiro, Shuntei, Eizan, Eisen, Kunisada (and as Toyokuni III), Toyokuni II, Kuniyoshi, Hokusai, Hokkei, Hokui, Hiroshige, Hiroshige II, Sadahide, Kunisada II, Hokushū, Ashiyuki, Yoshikuni, Sadanobu, Yoshitora, Yoshiiku, Yoshifusa, Kunichika, Yoshitoshi, Kiyochika, Chikanobu, Goyo, Shinsui, Hasui, et al. And that is only some of them. A who's who of Japanese prints artists. |

|

Buckwheat flowers |

蕎麦

そば

|

Source for soba.

The dried seeds of the buckwheat plant or Fagopyrum esculentum are

the source of soba flour. Shirley Booth in her Food of Japan (pp.

106-107) notes that buckwheat is not a grain, but "...it is the seed of [an]

herbaceous plant... that is ground and used. Because buckwheat grows well in

cooler northern climes (buckwheat groats, called kasha, are a staple

in Russia), noodles made from buckwheat are a feature of the northern

prefectures of Japan such as Nagano and Niigata. They are also more popular

in the Tokyo area than wheat noodles (udon), which in turned are

favored by the people of the western Kansai region around Osaka. However,

when soba noodles are made with 100 percent buckwheat flour they tend

to break up easily, and, although extremely good for you due to the rutin in

buckwheat, they are somewhat heavy and dense. Pure buckwheat is also

expensive, so buckwheat flour is often mixed with a percentage of wheat

flour - usually in a ratio of 40-60 percent."

The images to the left and below are shown courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. We would urge you to visit that valuable site.

Rick LaPointe wrote in The Japan Times of December 30, 2001: "Soba (buckwheat) was cultivated in Central Asia for as many as 4,000 years before the Christian era and made its way from China by way of Korea to Japan, where the first references to it date from the Nara Period (710-794). Buckwheat has been cultivated as a secondary crop in Japan since its introduction, and for many years was considered a peasant food, often eaten in times of famine." |

|

Buddha's Birthday |

灌仏会

かんぶつえ |

There are many mythic births. Literalists believe them to be true, but others see them as metaphorical or fanciful.

Athena was born fully grown and wearing a complete set of armor from the side of her father who was suffering from a headache. Eve was created from one of Adam's ribs. Whether this qualifies as a birth is not exactly clear, but that is basically incidental. Jesus was the result of a virgin birth which medieval Europeans believed to have been conceived aurally by the word of God delivered by the Holy Ghost. The historical Buddha's birthday does not vary greatly from these miracles. His mother stood and held the branch of a tree with her right hand and the Buddha came out of her side while she was in a state of bliss.

The date of the Buddha's birth varies from nation to nation for reasons of which I am ignorant. Generally it is linked to the 8th day of the 4th moon. In Japan it is celebrated today on April 8th by the hanamatsuri (花祭) or flower festival. The commemoration is called hanakuyō (花供養).

The practice of celebrating the Buddha's birthday became more widespread and formalized during the Sung dynasty (宋 960-1279). At this time the administrative-assistant leader of a monastery would prepare "the 'flower pavilion' (花亭), in which he placed the image of the new-born Buddha. Then he put two small ladles in a basin of hot incense-water... and arranged several offerings before the Buddha. Thereupon the abbot of the monastery (住持, jūji) entered the hall and led the ceremony; incense and flowers, candles, tea, fruits and rare delicacies were offered to the [Buddha]." Quoted from: Ancient Buddhism in Japan.

The ceremony changed over the ages. The sweet-tea or amacha washing rite [see below] was added during the Tokugawa era. |

|

The image shown above is not a representation of the Buddha on his birthday, but it is fine example all the same. It represents the "....Daibutsu at the Todaiji at Nara, which comes from an ehon published in the 1690's entitled Todaiji butsuden engi by an artist of the school of Hambei." This was sent to us by our generous contributor E. Thanks E!

Kanbutsu-e is the Japanese name for Buddha's birthday. The first kanji character 灌 'to pour' which is interesting since there is a baptism ceremony involved. In Japan from A to Z: Mysteries of Everyday Life Explained by James and Michiko Vardaman it states "...worshippers sprinkle a figure of the infant Buddha with sweet tea, or ama-cha, as a rite of bathing the Buddha called kanbutsue. The tea is symbolic of the scented water which nine dragons are said to have poured over the infant when he was born."

The figure of the baby Buddha is called the Tanjō Shaka (誕生釋迦) and the tea poured over the statue is amacha (甘茶). [This 甘茶 is hydrangea tea.] According to Basil Hall Chamberlain after the lustration ceremony the rest of the tea is purchased "...and either partaken of at home in order to kill the worms that cause various internal diseases, or placed near the pillars of the house to prevent ants and other insect pests from entering." Several sources say that if the amacha is mixed with ink and an incantation is written to ward off insects this is much more efficacious. In 1915 W. L. Hildburgh wrote "...when the new-born Buddha was receiving his first bath, the Tenjin... caused a spring to well up in the... garden enclosure of the palace, and that the water thereof contained a sweet-smelling incense having eight virtues. This divinely beneficent act is called Zuiki. A small image of the Infant Buddha is set up in a shrine in a temple's grounds (or, sometimes, in the homes of believers), and ama-cha (an infusion of hydrangea thunbergii) or kosui (water perfumed with incense) is poured over it by means of a small ladle. The liquid which has been used for the washing is sold at the temples, and is carried home in small bamboo tubes..." The author speculated that the reason this liquid was considered to work to deter insects might be because those same pests were souls which had been reborn in a lower form. (Below is a picture of Hydrangea serrata var. thunbergii posted by Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm.)

David Barnhill in his Basho's Haiku: Selected Poems of Matsuo Basho gives us an English translation of a haiku composed in the Summer of 1688: Buddha's-birthday:/ on this day is born/ a little fawn (kanbutsu no/ hi ni umareau/ kanoko kana). Barnhill also gives us a translation of one dealing with the death anniversary which is honored on the 15th day of the second month: Buddha's Nirvana Day/ wrinkled hands together/ the sound of the rosaries (nehane ya/ shiwade awasuru/ juzu no ota). In The Narrow Road to the Deep North and Other Travel Sketches Basho says "I was in Nara on Buddha's birthday, and saw the birth of a fawn. I was so struck by the coincidence..."

Busshō-e (仏生会) is another term for Buddha's birthday celebration. "...the so-called Busshō-nichi 佛生日, or 'Day of Buddha's Birth', is based on ancient Indian texts." Quoted from: Ancient Buddhism in Japan by de Visser

Helen Baroni in her volume The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Zen Buddhism defines kanbutsu as "Bathing the Buddha". "The rituals are also known as Yokubutsu." Later the author says: "The practice of bathing images of the Buddha to celebrate his birth originated in India. It became a popular custom in China by the seventh and eighth centuries, when it was transmitted to Japan. Prince Shōtoku Taishi (574-622) held the first kanbutsu ritual in Japan to celebrate the Buddha's birthday in 606." In Ancient Buddhism in Japan it says that the Bussho-e and its counterpart, the Urabon-e (于蘭盆会) honoring Buddha's death, were instituted by the Empress Suiko in 606. The Urabon-e is known as the festival of lanterns. W.G. Aston in his translation of the Nihongi also notes that the practice of enshrinement of statues of the Buddha began in the same year.

De Visser notes that in one of the sūtras that after his birth and washing and taking his first seven steps that "All Buddhas of the ten quarters are born at midnight of the 8th day of the 4th month, because at that time, between spring and summer, all evil is ended, everything has fully matured, poisonous vapours are not yet spreading, there is neither cold not [sic] heat, and the atmosphere is harmonious and agreeable."

During the Tokugawa period "In all sects, except the Jōdo Shinsū, on the Buddha's birthday a temporary chapel (假堂, kari-dō) is prepared, and its roof is adorned with flowers of the season.... In this chapel the image of the new-born Buddha, standing upon the lotus flower which after his birth arose from the earth, is placed in a copper basin with 'sweet tea' and the visitors of the temple with small ladles pour the amacha over the Buddha's head. Then they take the liquid home in small vessels, and after having mixed it with their ink (i. e. having whetted their inkstone therewith) they write the following verse (uta): 'On the lucky day, the mighty eighth of the month of the hare (the 4th month), we are sure to execute the larvae of the insects (kumisage-mushi)'. If one pastes this paper on the wall in his house, he is believed to escape the evil of the centipedes and other noxious insects." Quoted from: Ancient Buddhism in Japan by de Visser, p. 56 |

||

|

|

||

|

Buisson, Dominique |

ドミニク・ビュイソンさん |

Author of The Art of Japanese Paper 1 According to Éditions Picquier: "Dominique Buisson was born in 1947. Associate professor of visual arts, he is the author of numerous publications on Japanese aesthetics, catalogs of exhibitions, art books. In 1992, he was appointed scientific advisor to the Asian Arts Museum in Nice and in 1998, cultural ambassador for the city of Shizuoka in Japan." |

|

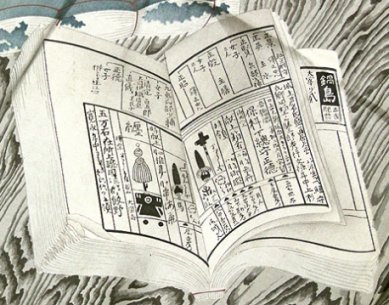

Bukan |

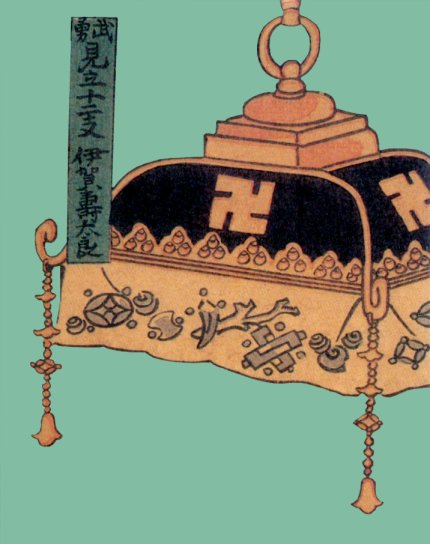

武鑑

ぶかん |

A book of heraldry - "It also mattered to the Edo townsmen and merchants who had access to the handbook of heraldry, the daimyo bukan, which listed the feudal lords, their principal vassals, their kokudaka, their heraldry and insignia, the size of their entourage, their mansions, and the schedules of their rites of homage to the shogun, for all this was highly relevant to the commercial dealings with the daimyo's samurai and provided, so to speak, their credit rating." Quoted from: The Making of Modern Japan by Marius Jansen, p. 39.

Peter Korniki noted that: " 'it remains remarkable' in the light on prohibition on foreigners purchasing bukan..."

We found the image to the left at Pinterest. |

|

"The directories of the Bakufu officialdom known as bukan 武鑑 were another form of serial publication, for they were always available and constantly updated. Indeed, most surviving examples show signs of alterations to the printing blocks as publishers attempted to keep pace with personnel changes in the Bakufu, even making changes on a monthly basis by the end of the Tokugawa period. Directories of this sort were in existence in the early seventeenth century, but it was in 1687 that a bookseller affiliated to the Bakufu as an official publisher issued one with the word bukan in the title and from then onwards it was the standard term. At the end of the seventeenth century various publishers, all based in Edo, were producing bukan but by the early eighteenth century the market had been cornered by cornered by Suwaraya Mohee and Izumoji Izuminojō 出震寺和泉*" Quoted from: The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth Century by Peter Korniki, p. 69.

"...identifying banners had practical purposes. There were officials known as gezami (下座見), stationed at border crossings and castle gates, who were responsible for recognizing important individuals and commanding bystanders to pay appropriate respect. Samurai lords also had retainers with similar duties that accompanied them when travelling.[6, p.16] Given that such officials needed to recognize mon, a compendium of heraldry such as this would have been a useful reference." Quoted from: O-umajirushi: A 17th-Century Compendium of Samurai Heraldry, p. xi. |

||

|

|

||

|

Bunraku |

文楽

ぶんらく |

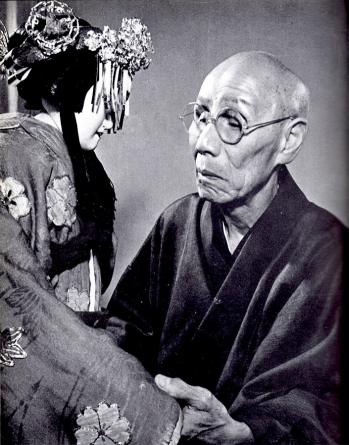

Puppet theater: "...the general term for the classical puppet theater. Buraku consists of three elements - the jorūri narration, originating in the 15th century accompanied by the biwa, the shamisen, instrumental accompaniment which replaced the biwa around 1560, and the addition of manipulated puppets (ningyō) introduced around 1600. It took its present form as ningyō-jorūri in the 17th century when Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1724) wrote many plays for Bunraku. The main dolls (ningyō) are manipulated by three puppeteers while the narrator (tayū) recites the story to the accompaniment of shamisen. The unique charm Bunraku lies in the harmony of the skillful actions of the puppets manipulated by puppeteers and the deep voice of the jorūri singers telling a story to the sound of shamisen, which exquisitely conveys feelings and moves the audience to tears and laughter. The stylized movements of the puppets can be seen in the acting techniques of the Kabuki theater, which has adapted many Bunraku plays." Quoted from: Japanese-English Dictionary of Japanese Culture by Kojima and Crane, p. 28.

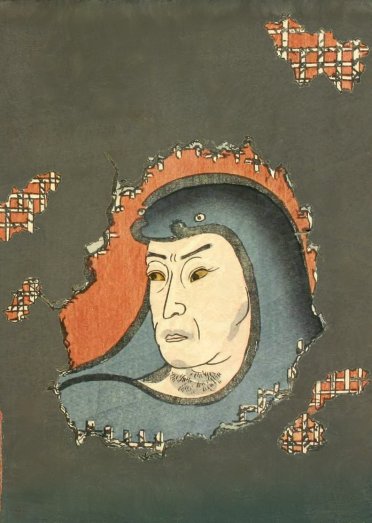

Bunraku doll head in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The image to the left was posted at Wikipedia commons. |

|

Busshukan |

仏手柑

ぶっしゅかん |

The Hand of Buddha, a citron, Citrus medica var. sarcodactylis - "Buddha's hand... an aromatic but inedible ctiron that is said in its irregular shape to resemble the hand of Buddha. Its Chinese name is a homophone for the words "happiness" and "longevity" and the Chinese have designated it, the peach, and the pomegranate the Three Abundances. Objects formed inthe shape of a Buddha's hand were favored by Chinese literati of later dynasties, and in Japan the citron is also regarded as an accoutrement of literati and tea-ceremony masters." Quoted from: Symbols of Japan... by Merrily Baird, p. 57.

The curatorial files from the museums of Aberdeen, Scotland state: "...a sacred fruit, which has been important in both Chinese and Japanese culture for many centuries. The 'Hand of Buddha' is a religiously significant mutation of the citrus plant, which produces fruits resembling large rough lemons with squid like tentacles rather like gnarled fingers. They are often brought into the home at New Year as they are thought to bring good fortune. Buddha's hand fruit is very fragrant and is used for perfuming rooms and personal items such as clothing.

The photo of the jade citron to the left was posted at commons.wikimedia. It is from the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco and is of Chinese origin. The photo above was posted at the same site by Fanghong. |

|

Butsudan |

仏壇 ぶつだん |

A family's Buddhist household shrine or altar. The ihai or memorial tablet of a deceased relative is placed on a stand within, on - if it is a shelf, or before this shrine.

Below is a close up detail of a butsudan - a very fancy butsudan - posted at commons.wikimedia by Corpse Reviver.

|

|

How old is the concept of the butsudan? According to Sampa Biswas in Indian Influence on the Art of Japan (pp. 42-3) it started in the time of Emperor Temmu. "...in AD 685, orders were sent to all the provinces to build in each house, a Buddhist shrine where an image of the Buddha with Buddhist scriptures should be installed and offerings of food be offered there.

In a book entitled The Social Evil in Japan put out in 1908 by the Methodist Publishing House says that "...nearly all brothel keepers are devout Buddhists... The inmates of brothels are urged to perform their devotions before the Butsudan... and endeavors are made by keepers and priests to give a religious halo to the women's shame..."

A small portable shrine is called zushi (厨子). |

||

|

|

||

|

Butsuzō zui |

仏像図彙 ぶつぞうずい |

"In 1690, Gizan (1648–1717), a Jōdo-sect monk from Kyoto, well respected as a scholar of Buddhist history, published the first edition of the authoritative guide to Buddhist deities and implements, Illustrated Compendium of Buddhist Images (Butsuzō zui). Ever since its publication, Butsuzō zui has served as an authority for aspiring Buddhist painters, sculptors, craftsmakers, and the lay public who needed to know the correct iconography and appearance of the pantheon of Buddhist deities, sect patriarchs, and Buddhist accoutrements." Quoted from: In Faith and Power in Japanese Buddhist Art, 1600-2005 by Patricia Graham, p. 110. Dr. Graham notes that earliest edition differs considerably from one published in 1783. |

|

Camel (One hump) |

単峰駱駝

たんぽうらくだ |

Anyone who has visited these pages knows that at times I am rather goofy. Camels don't count for a lot in Japanese prints, although they do appear at times, but if you would like to see a great print of one then click on the link to the right. 1

Keiko Suzuki gave a translation of a poster for the arrival of the first camels in Edo in 1824. It says: "...“camels’ urine heals poor circulation, scabies, and swellings, and their hair works as a charm against smallpox and talismans. As both camels have a gentle nature and make an affectionate couple, with one glance at them one can catch the same affectionate nature. With their gentle nature, they are not intimidated even by tens of thousands of people in front of them. They are truly the rarest animals of all times”..." |

|

Chanoyu |

茶の湯

ちゃのゆ |

The tea ceremony: "Chanoyu, the ceremonial preparation and consumption of tea that was first formalized by the Kyoto monk Murata Shukō (1422-1502) in the fifteenth century, became a highly popular pastime with courtiers, daimyō feudal lords, priests, and wealthy merchants alike." Quoted from: Master Potter of Meiji Japan: Makuzu Kōzan (1842-1916) and His Workshop by Moyra Claire Pollard, Oxford University Press, 2002, p. 9.

The image to the left was posted originally at Flickr by Renfield Kuroda. We found it at Wikimedia.commons. |

|

Cha-soba |

茶蕎麦

ちゃそば |

Soba made with green tea - Often served cold on bamboo slats with a dashi-soy based dipping sauce and some horseradish.

The image to the left was posted at Flick by punzy.

For more on soba in general click on the number 1.

|

|

Chaya-zome |

茶屋染 ちゃやぞめ |

A dyed fabric technique popular during the Edo period. |

|

Chigaidana |

違い棚 ちがいだな |

Staggered shelves: This element became a standard feature during the Muromachi period (室町時代: 1392-1568) of the residences of the military aristocracy and were placed next to the tokonama (床の間), a recessed alcove reserved for the display of a single hanging scroll along with several objets d'art. The chigaidana were built into the room itself. William Deal in his Handbook to Life in Medieval and Early Modern Japan said that there were generally just two shelves and that they were often made from special woods for a more decorative effect.

The photo shown above was taken at Chishakuin Temple. It was taken by Christian Kaden and post at Flickr.

Michael Jeremy and Michael Earnest Robinson in their Ceremony and Symbolism in the Japanese Home state: "The chigaidana may appear on the surface to be nothing more than a area of shelving and cupboard space. In fact, however, it is created with great care and with great respect for the proportions which are involved. There is invariably an upper and lower cabinet space and two split-level shelves which suggest the recurring symbolism of anything that is uneven, unequal, and therefore life-giving." |

|

Chihaya |

千早 ちはや |

The sacred white robes worn by Shinto shrine maidens or miko (御子). |

|

Chikurin |

竹林 ちくりん |

A bamboo thicket. Often used as a decorative motif. It is also referred to as a takebayashi (高林). |

|

Chikushōdō |

畜生道 ちくしょうどう |

In Buddhism this is the animal realm that people are reborn into if they have led stupid or ignorant lives - according some scholars. |

|

Chi no ike jigoku |

血池地獄

ちのいけじごく |

Blood Pool Hell - a place in hell meant just for women. In The Tale of the Fuji Cave, as translated by R. Keller Kimbrough, it say: "It’s true that both men and women fall into hell, but many more women do than men. Women’s thoughts are all evil. Still, women are forbidden to approach men on only eighty-four days a year. Women don’t know their own transgressions, which is why they fail to plant good karmic roots. It’s a shame, you know."

The image above was posted at Flickr by Paul Allais. The one to the left was also posted at the same site by Katie.

Bernard Faure in The Red Thread: Buddhist Approaches to Sexuality (p. 119) he recounts the tale of a Wŏnhyo who encounters two women. One of them is working in a field harvesting rice and refuses to share any of it with Wŏnhyo. The other one is "...washing her menstrual band in a stream, the ultimate act of defilement, for which women have been condemned to fall into the Blood Pond Hell. When she offers some of that contaminated water to Wŏnhyo, the latter, undaunted, gladly accepts. Later he finds out that these two women were manifestations of Avalokiteśvara, who praises him through the song of the bluebird."

For more information see our entry on Tateyama on our Si thru Tengai page. |

|

Below is what I believe is the left panel from a Kuniyoshi triptych in the Tokyo Metropolitan Library collection. Among other things, it shows the Blood Pool Hell in the center. Right above the most visible standing woman in the pool is the figure of Datsueba, the Old Hag of Hell. She is the one who takes the clothes off of the souls that arrive in Hell and hangs them on the tree behind her. Or, if they arrive naked, she takes their skins and does the same thing. Across the river is the golden figure of Jizō, the patron saint who saves the souls of small children and/or even the still-born ones, I believe. You can see the figures of the small naked children near him.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Chinowa |

茅の輪

ちのわ |

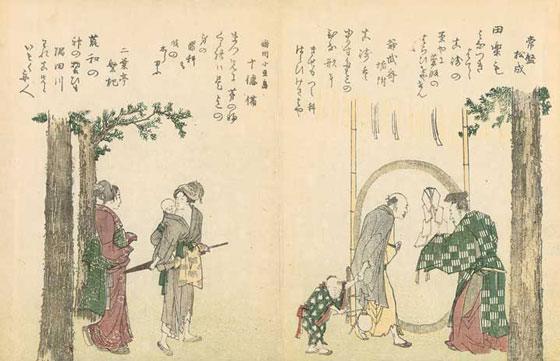

Cogon grass ring (through which people pass during summer purification rites). This ring is also called a suganuki (菅貫). Brian Bocking wrote in his A Popular Dictionary of Shinto on page 16: "Chin-no-wa A great ring up to 4m in diameter of twisted miscanthus reeds (chigaya) set up in shrine grounds to exorcise misfortune for those who walk through it. Chi-no-wa are used throughout Japan especially at the Ōharae festival on June 30 and December 31st."

The image to the left is from a ca. 1802 Hokusai print showing a visit to the Masaki Inari Shrine. It is in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. A text from the Asia Society says: "Parents and children make a pilgrimage to Masaki Inari Shrine on the west bank of Edo’s Sumida River to partake of an annual Shinto ritual, an end-of-summer purification rite held on the last day of the sixth month. Visitors pass through a large hoop made of chigaya grass tied with paper to symbolically exorcise spiritual impurity." |

|

Edoardo Chiossone |

エドアルド.キヨッソーネ |

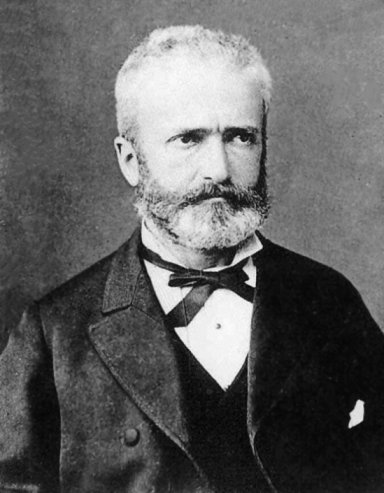

Born on Jan. 21, 1832 near Genoa, Italy, and died of heart failure in Tokyo on Apr. 11, 1898. He attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Genoa and trained mainly in engraving. In 1862 he started working for the Italian National Bank. In 1867 he was sent to Germany to hone his skills in creating banknotes. Because of the political situation in Italy he stayed on in Germany. ¶ In the meantime, the new Japanese government was trying to get control of that nation's finances. Numerous provinces had printed their own currencies. The Meiji goverment was determined to put a stop to that. So, they hired a number of skilled European printers to help them get a handle on the situation. Chiossone was one of them. He had been working for the firm that produced the new printing plates for paper currency ordered by the Japanese government. ¶ Chiossone arrived in Japan in 1875. He signed a contract to become the Chief Engraver of the Paper Money Bereau. He produced numerous plates for stamps and banknotes. ¶ He bequeathed a large collection of Asian art and artefacts to his alma mater in Genoa. Eventually this was moved to the Museo d'Art Orientale. |

|

Chirimen |

縮緬 ちりめん |

While this term can mean crepe in general terms it is also the term used for silk crepe. However, in this case it refers to a category of Japanese woodblock prints.

Detail from an early (1814) Kunisada chirimen print.

Literally it means "shrink (shrivel, shorten, condense, etc.) fine threads". 1 |

|

However, we can't avoid the general reference to chirimen as creped silk. Helen Minnich in her Japanese Costume & Makers: And the Makers of Its Elegant Tradition was talking about the use of blue dyed clothing historically and noted that "From very early times very dark blue was never a color for highranking personages but was worn mostly by coolies and servants and considered wholly outside the pale of fashion. Just one exception was the very long haori of dark-blue chirimen crepe which was worn by all physicians as a mark of their profession."

A detail of a piece of silk chirimen posted at Wikimedia Commons by Soseki's cat. |

||

|

|

||

|

Chō |

蝶

ちょう

|

Butterfly: Dower did note in his The Elements of Japanese Design (p. 88) "To a large extent [the butterfly] symbolized the other side of the warrior's harsh life - his susceptibility to the effete graces of the courtly society." Of course, that is Dower's opinion. For a different take on this see our entry on Ageha no chō on our first index/gloasary page. ¶ One more note from this contributor: I make a ton of mistakes. Maybe you have noticed. Nothing is gospel. If you disagree with me on anything posted in this site please contact us. I don't mind being wrong, but one caveat, make sure you back up your point with credible information.

In China, according to C.A.S. Williams in his Chinese Symbolism and Art Motifs (pp. 51-2) the butterfly "...is an emblem of joy. It is a symbol of summer..." and a sign of conjugal felicity. "...in fact it might almost be called the Chinese Cupid." This belief it would appear has its origins in Taoism.

However, in Japan in the 7th century seems to have been a rather adverse reaction to Taoist beliefs. "Although numerous plants and animals are mentioned in the 8th-century poetry anthology Man'yōshū there is not a single reference to the butterfly. In an attempt to explain this some writers point out that in 644, according to the chronicle Nihon shoki (720), the government proscribed a popular variant of Taoism that venerated the larva of the swallowtail butterfly as a god."

Later in the Tale of Genji the butterfly was thought of as something "loveable." By the time of the Muromachi period (1333-1568) butterflies were appearing on armor and furniture. (Source and quote from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 1, p. 226, entry by Saitō Shōji)

Lea Baten in her volume Japanese Animal Art: Antique and Contemporary (p. 97) adds a little more information. "White butterflies are thought to be spirits of the living as well as the dead, and may not be captured - the fragile insect is a symbol of immortality, due to the successive stages of its metamorphose from egg to caterpillar and from cocoon to adult insect. Its graceful fluttering from flower to flower...is easily compared to the fickelness of women who often change lovers (in search of money.)

The images to the left are details from a print by Chikanobu while the ones above and below are by Kunisada. |

|

Alfred Koehn in his article "Chinese Flower Symbolism" noted that "Many are the pictures of Cats looking up at, or attempting to catch, Butterflies. They express the hope for a happy Old Age because the Cat's name, mao 貓, suggests another mao 耄, a person well over seventy, and the Butterfly's name, hu-tieh 蝴蝶, brings to mind the differently written tieh 耋, eighty years of age."

|

||

|

|

||

|

Chōai |

丁合 ちょうあい |

In book publishing the chōai is the worker who makes sure the pages align correctly. |

|

Chōbunsai Eishi |

鳥文斉栄之

ちょうぶんさい.えいし |

Artist 1756-1829:

"Eishi was of unusually high rank for an Ukiyo-e artist, his grandfather and great-grandfather having both served as Chief of Accounts (kantei bugyō) for the Bakufu, with , with a stipend of 500 koku, court rank of Lower Fifth Grade and the title of Governor of Tamba Province. This permitted Eishi to study painting under Kanō Eisen'in Michinobu (1730-90), head of the Kanō school and Chief Painter in Attendance (oku-eshi) to the Shōgun Ieharu after 1781. The nineteenth-century compilation of painters' biographies, Koga bikō, even records that Eishi was appointed as Ieharu's 'painting companion' (om-ga no tomo), though he was forced to retire after only three years of service because of ill health, presumably before Ieharu's death in 1786. ¶ It was at about this time that Eishi must have taken the decision to 'drop out' of the Bakufu bureaucracy and painting academy and become an artist of the popular Ukiyo-e school. Such a transformation was not entirely unprecedented: it was at this time that Sakai Hoitsu, second son of the Lord of Himeji, was studying Ukiyo-e painting with Utagawa Toyoharu. Eishi never relinquished his high status, however, and some of his best later Ukiyo-e paintings are signed with titles such as 'Painted by Eishi, High Official of the Ministry of Ceremonial, Tokitomi of the Fujiwara Clan' (Jibukyō Eishi Fujiwara Tokitomi hitsu'). ¶ His earliest works in Ukiyo-e style were illustrations for a kibyōshi novel published in 1785, and in general his colour prints of the later 1780s follow the prevailing style of Kiyonaga, with a particular penchant for courtly themes, as in his series of triptychs reworking chapters from Tale of Genji in modern settings, printed entirely in muted colours. In the 1790s he produced a steady stream of prints of standing or seated beauties against simple backgrounds that show the influence of Utamaro, but have a particularly refined tone (often likening the courtesans to female poets from the Heian period) and a style that favoured broad sweeping curves in the drapery. ¶ Eishi was one of the most prolific of Ukiyo-e painters, and although his corpus of several hundred paintings has yet to be studied systematically and in detail, there are a handful of dated works that fall between 1795 and 1826. The figures show the same elegant line and refined poses as in the woodblock prints and are often set in ink-wash landscapes deftly painted in the Edo-Kanō technique learned in his youth. Eishi was often prone to repeating successful compositions, and, for example, more than a dozen versions survive in various formal and informal painting styles of a handscroll, The Gods of Good Fortune Visit Yoshiwara, based on a comic essay of 1781, Kakure-zato no ki ('Record of the Hidden Village'), by Ōta Nampo. Nampo was a leading figure in popular literature from the 1780s to his death in 1823, and his kyōka (crazy verse) or kanshi (Chinese-style poem) inscriptions are often to be found on Eishi's paintings: Eishi did several versions of a portrait of the famous writer. ¶ In addition to paintings on Ukiyo-e themes Eishi did several versions of a handscroll, The Battle of Sekigahara (fought in 1600), presumably for military patrons. It is with precisely the same touch Eishi used to paint the crests of Yoshiwara courtesans on their lanterns that he now painted the emblems of military families on their battle standards: nothing could illustrate more neatly the duality of the world he inhabited. It is further recorded that on one occasion the retired Emperor Gosakuramachi saw a painting by Eishi, Sumida River, and was sufficiently taken with it for the work to enter the Imperial collections. After this Eishi occasionally impressed a large seal on his paintings reading 'Viewed by the Emperor' (tenkan). ¶ Almost thirty pupils of Eishi are recorded, the most prominent being Eishō, Eiri and Eisui, who are known for thier colour prints of the 1790s showing bust portraits of famous courtesans. Most other pupils are known only by a few paintings in Eishi style, and it seems that after c. 1800 the new, brash tenor of commercial printing - epitomised by the Utagawa school - was no longer in tune with Eishi's fine sensibilities. After this time he produced only paintings.

Quoted from: Ukiyo-e Paintings in the British Museum by Timothy Clark, p. 122.

The image to the left is from the collection of the Brooklyn Museum. We found it at commons.wikimedia. |

|

Chōchin |

提燈 / 提灯

ちょうちん |

A lantern made of bamboo covered with paper or silk with a candle placed inside. It can be folded flat when not being used. Formerly they could be used like flashlights at night.

Two of three examples shown here represent various interpretations of the chōchin in print form from three different periods. The one at the top left is from a Kunisada print with a bijin balanced precariously on a railing while trying to hang a lantern (ca. 1840). The image in below that is by Hiroshi Yoshida showing the interior of a lantern maker's shop with several of these shown collapsed on the ground (1926). Hanging them stretches them out to the full form. The third example below is by Kiyochika and shows a cat which has caught a mouse by its tail as it is trying to escape through a lantern lying in its side. Notice the mouse's snout sticking out of the left side of the lantern (ca. 1880). My money is on the mouse.

|

|

Chōkei-sō |

頂髻相

ちょうけいそう |

The protuberance found at the top of the head of a Buddha. There are 32 different physical aspects of the Buddha of which the chōkei-sō is simply one.

To the untrained and especially typical Western eye the area at the top of the Buddha's head appears to be a simple hairstyle. However, it is anything but that. Years ago I was told by an expert in the field that when the Buddha attained enlightenment while meditating under the bodhi tree his brain expanded enormously and his skull had to expand to accommodate it. In Sanskrit it is referred to as the usnisa - pronounced usnisha.

The chōkei-sō is also known as the nikkei (肉髻).

For several days I was struggling to find the Japanese term for the usnisa. Then I heard from an old friend who is a scholar and Japanophile - Karen Mack. A few minutes late I had my answer.

Karen has lived in Japan for years and for some time has been offering a fascinating blog devoted to most things Japanese. I would urge you to take a look and bookmark it for future reference.

|

|

Chōki-bune |

猪牙船

ちょうきぶね |

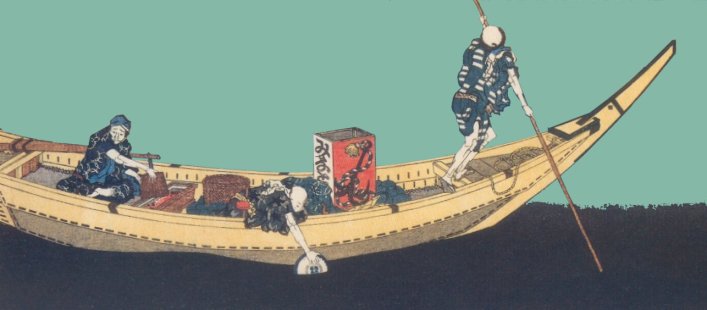

A 'boar's tusk boat'. So named because of its shape. It was used to ferry passengers and goods.

The detail to the left is from a print by Hokusai.

In Women of the Pleasure Quarters: The Secret History of the Geisha by Lesley Downer, in her glossary section it defines 'chokibune' as a "light, swift, single-oared boats, used to take customers along the River Sumida to the Yoshiwara pleasure quatrer." |

|

"Ferries were but one of a number of different types of vessel on the rivers of east Japan, each type a slightly different size and bearing a different name. The boats of the Sumida were described by the politician and patron of horse-racing Arima Yoriyasu (1884-1957) in an essay entitled 'Sumidagaiva no fune' (The boats of the Sumida river) written in 1916 and first published in Kyōdo kenkyū (Local research). Arima had a villa along the river in Hashiba, and no doubt it was from there that he observed the variety of boats. The little water-borne taxi boats known as chokibune ('boar's tooth boat,' named, according to one theory, for its resemblance to the tusk of a wild boar) had, Arima wrote, all but disappeared. Equally, the old yakatabune were hardly to be seen any longer. These were the pavilioned pleasure boats under whose elegant eaves geisha entertained summertime party-goers. Arima described the various types of fishing boat still in use and the boats for the transport of goods including the takasebune, only recently introduced to the Sumida, with their large high bow making them look from the front like a toad, whence their alternative name of gamabune, or toad boat. These were used for the transport of potatoes, grains, beans, and firewood from Kawagoe. The most common form of vessel was the denmasen, conveying goods between markets and wholesalers. The chabune, 'tea boat,' was a smaller equivalent used mainly as a lighter to carry goods from larger boats down the waterways to the quays in town." Quoted from: Japanese Capitals in Historical Perspective: Place, Power and Memory in Kyoto, Edo and Tokyo, p. 213. |

||

|

|

||

|

Chōshi |

銚子

ちょうし |

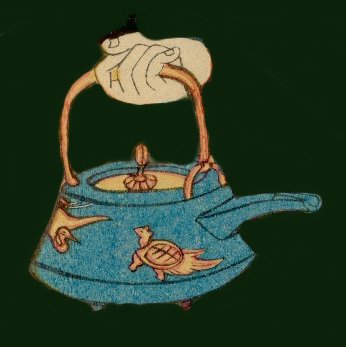

Metal kettle used for warming and serving sake.

According to the Kenkyusha's New Japanese English Dictionary chōshi means "a sake-holder" or "a sake-bottle".

In Saké: A Drinker's Guide by Hiroshi Kondō it says on page 90, in the section on 'Warming Saké': "Almost everyone knows that saké is served warm in small pitchers (called tokkuri or o-chōshi), and that it is drunk from tiny cups (sakazuki or o-choko)." Kondō later adds: "Many connoisseurs insist that warming saké distorts its true taste, and few people would warm a truly outstanding saké. Heating a mediocre saké will only emphasize its defects. But there are some occasions when saké is best warm. A dry saké warm, for example, will reveal its distinctive nose and flavor. And in the Edo period, the favorite dictum of connoisseurs was: 'The saké should be warm, the cuisine sashimi, and the pourer a beautiful woman.' " |

|

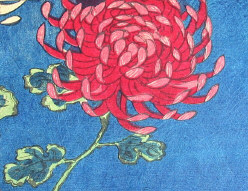

Chrysanthemum (Kiku) |

菊

きく |

One of the "Four Gentlemen" or Shikunshi which are flowers which mirror positive human traits. The other three are plum, orchid and bamboo. Borrowed from the Chinese and linked to confucian concepts. 1 |

|

Chūban |

中判 ちゅうばん |

Print size approximately 10 1/4" x 7 1/2" |

|

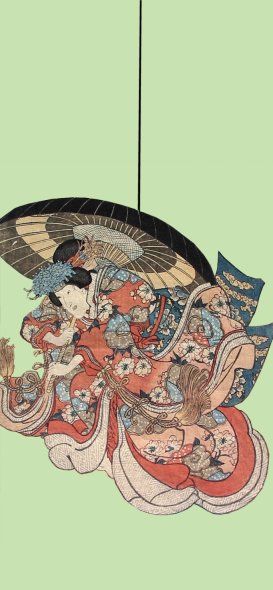

Chūnori |

宙乗り

ちゅうのり |

Riding in air: A stage trick or keren of an actor flying, via ropes (or wires) and pulleys, over the stage or audience.

Definition from: Kabuki Plays on Stage: Darkness and Desire, 1804-1864, edited by James R. Brandon and Samuel L. Leiter, University of Hawai'i Press, 2002, p. 358.

Samuel L. Leiter also gives chūnori as 中乗り or middle-riding. The chu (宙) we have chosen to use can mean space, mid-air or sky, but in combination with other kanji can mean everything from cosmology to somersault to space station and that is only three examples of many.

"Flying is known as chunori and has become the specialty of Ichikawa Ennosuke III [born 1939], who has applied the device to great effect, particularly in his performance as Nikki Danjo in the play Date no Ju Yaku and as the fox Tadanobu in Yoshitsune Senbai Zakura. The character may either fly across the stage or out into the audience. The latter is achieved by a winch set up over the hanamichi, running from the main stage to the top of the third floor of the theater. Using a special costume under which a harnass is concealed, the actor takes off near the main stage and rises up to the top floor, where he disappears into a specially constructed room in the seating area."

Quoted from: Kabuki: A Pocket Guide, by Ronald Cavaye, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1993, p. 92.

The image to the left is a doctored image from a vertical diptych which shows the Princess Sakura leaping from a balcony. The wire does not appear in the print. However, this leap could only have occurred safely with the use of a chūnori. Below is the undoctored image. Click on it to see the full diptych. "One of the chief types of trick-effect acting (keren), flying is a technique by which a magical creature or ghost is made to soar through the air. A metal fitting on the costume is fastened to a wire that lifts the actor into the air. He may fly out over the auditorium, following the path of the hamamichi below, to the balcony. He wears a parachute-like harnass (renjaku), and a man in the balcony runs the main pulley, while another controls the waist wire, and another the crotch wire." ¶ "Chūnori itself seems to have vanished in the prewar years. The negative reaction to it began in the late nineteenth century when it was objected to by Ichikawa Danjūrō IX (although he had flown as Jiraiya... in his youth). Chūnori was reintroduced only in 1967..."

Quote from: New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of kabuki jiten, compiled by Samuel L. Leiter, 1997, p. 63.

Karen Brazell and James Araki in their Traditional Japanese Theater: An Anthology of Plays (Columbia University Press, 1998, p. 527) note that this technique was also used in puppet theater where the person holding the puppet flew through the air.

"The Fox-Tadanobu in Yoshitsune Senbon Zakura performs the best-known chūnori. The actor flies in a horizontal position in this role." [Note: While the image above from a print by Kuniyoshi does not show the figure in a horizontal position that is the way it is most frequently performed.]

Quote from: New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of kabuki jiten, compiled by Samuel L. Leiter, 1997, p. 64. |

|

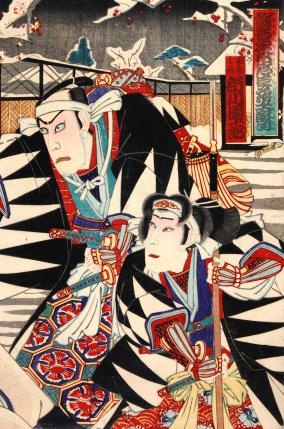

Chūshingura |

忠臣蔵

ちゅうしんぐら |

"The Treasury of the 47 Loyal Retainers" - probably the most popular tale adapted for both kabuki and bunraku. Often the subject of ukiyo artists.

The dentate pattern on each of these prints here are a give away that these are Chūshingura-themed prints. But not all prints devoted to this story show these designs. "The distinctive dentate pattern on the coats is an iconographical motif which represents the inescapable progress of day and night, symbolizing unfailing loyalty."

Quoted from: 'Mitate kokkei Chūshingura. Hiroshige's humorous parodies of the Loyal Retainers' by Pierre Wijermans and Henk Herwig, fn. 32, p. 73.

The image to the left by Kuniyoshi is in the collection of the British Museum. The one immediately above is by Kunisada III is from Ritsumeikan University. The one above that one is by Kuniaki and comes from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. All three show ronin from the Chūshingura. |

|

Clark, Timothy |

ティモシー・クラーク |

Author and scholar - curator in the Department of Japanese Antiquities at the British Museum 1 |

|

Dachō |

鴕鳥

だちょう |

Ostrich - normally we wouldn't add something like this entry, but we felt it was too good not to. Why? Because so far we can find out nothing about ostriches in Japanese culture or history. We will add it if it ever shows up.

|

|

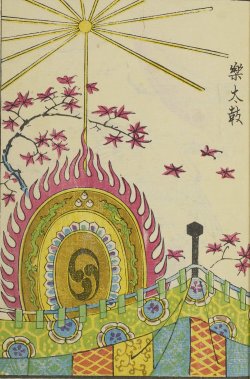

Dadaiko |

大太鼓

おおだいこ |

A large, elaborately decorated drum often with a surrounding flame-like frame. The ones with the flame ( 火焔) motif are referred to as kaen dadaiko (火焔大鼓).

The oldest officially administered temple in Japan is the Shitennō-ji (四天王寺) in Osaka. It was built by Prince Shōtoku (聖徳太子: 574-622 A.D.) who played the 'flame drum' at its opening. |

|

Daigane |

台金 だいがね |

"The wig consists of a copper base (daigane) that is moulded to the exact shape of the individual actor's skull and onto which the hair is attached." Quoted from: A Guide to the Japanese Stage: From Traditional to Cutting Edge by Cavaye, Griffith and Senda, p. 75. |

|

Daikon |

大根

だいこん

|

The Japanese radish or Raphanus sativus: According to Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm this plant was native to Central Asia and coastal areas of the Mediterranean. It was cultivated in ancient Egypt and first appeared in Japan some time during the Jomon Era to Yayoi Era, i.e., from 10,000 to 2,500 years ago. The white to pale purple, 4 petaled flowers bloom in March and April. It is a member of the Brassiaceae or mustard family. in ancient times it was referred to as the suzushiro (すずしろ). (The photos of the plant itself are shown courtesy of Shu and we would encourage you to visit his wonderful site.)

Merrily Baird in her Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design (pp. 95-6) notes that the daikon "...is a dietary mainstay that enjoys a reputation for ensuring good health." In ca. 815 "...Heian court officials began to observe a pair of Chinese-inspired festivals known as the Medicinal Offerings and the Tooth Hardening (okusuri and hagatame)." Wine and special foods including radishes were offered to the Emperor at New Year's. The daikon was thought to harden the teeth and hence ensure good health. "A century later, the court began observing on the seventh day of the New Year Festival of Young Herbs. This involved the preparation of a gruel of seven auspicious plants, including the radish..."

During the Muromachi the daikon took on new significance: "...it symbolized beliefs, originally introduced by Tendai Buddhism in the ninth century, that even lowly forms of life such as vegetables could attain a state of Buddhahood" To the Zen sect it was linked to the simple, monastic life and was popularized through paintings.

In the Edo period the daikon came to be linked with Daikokuten, one of the Seven Propitious Gods. "Forked radishes in particular can also symbolize a female's wish for a child, and, in this context, they sometimes are donated to shrines."

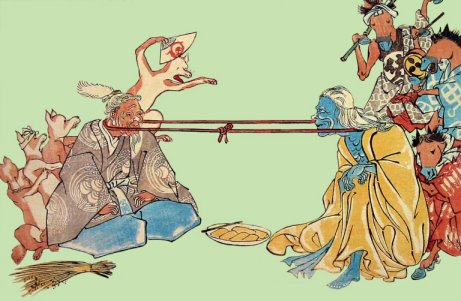

[Note the dancing radish to the below. It is a detail from an early print by Kunisada where a seated male figure is sternly considering this life sized taproot. Is the radish dancing gleefully because it has attained enlightenment a la the Tendai sect? Is is meant to represent a woman's desire for child? Or, could it be something else? Personally, I haven't the slightest.]

|

|

Daikon mon |

大根紋

だいこんもん |

Japanese radish crests: According to John W. Dower in his The Elements of Japanese Design (pp. 76-77) the radish is "One of the seven plants of spring,"...[and it has] numerous superstitious and religious connotations."

He continues: "In ancient religious ceremonies it was associated with parsley and shepherd's purse as a particularly auspicious food for certain occasions. In esoteric Buddhism, a forked radish was the symbol of Shoten (Vinayaksha), the elephant-headed god, and this obvious fertility symbolism came to bode prosperity and success."

|

|

Daikoku |

大黒

だいこく |

One of the Seven Propitious Gods. He is the god of wealth and harvest and can often be identified by his large sack of treasures and his wooden mallet.

The image above was taken by Fg2 and can be found along with many others at http://commons.wikimedia.org/.

"The name Daikoku, the Great Black Deity, is a direct translation of Mahākalā, the name of the Hindu deity already adopted by Buddhists in India. ...he is described as a manifestation of Mahāvairocana who can subdue demons. The Sutra of the Wisdom of the Benevolent Kings speaks of Daikoku as a god of war, and in Buddhist iconography he is often portrayed with a fierce and angry countenance. He is also, however, described as a great bodhisattva of good fortune who shares his wealth with the poor, and it is for this characteristic that he is known as one of the Seven Gods. Well fed and smiling, Daikoku carries a sack of good fortune over one shoulder; in his other hand he holds a small mallet for hammering out wealth (uchide no kozuchi). He wears a loose cap or headcloth and typically stands on two straw bales of rice. Here, too, a lesson in moderation is to be found in his appearance: the loose headcloth prevents him from looking up and getting too ambitious; the two bales represent an essential sufficiency that should keep him content." (Quoted from: Practically Religious: Worldly Benefits and the Common Religion of Japan, by Ian Reader and George Joji Tanabe, University of Hawaii Press, 1998, p. 158)

"There is another agrarian moral about the virtue of labor to be learned from the homonyms for the mallet (tsuchi) that hammers out wealth (takara). "Tsuchi" also means dirt or earth, and "takara" can also be read as two words: "ta kara," (from the rice field). The straw bales of rice, therefore, do not fall freely from heaven but are produced by 'hammering the earth' and working the fields." (Ibid.) |

|

"Because wealth was traditionally measured in terms of good harvest, Daikoku has usually been pictured standing on two or three bales of rice while a mouse, his messenger, scampers about in search of fallen grains. In rural Japan, Daikoku became a deity of the rice paddies. Because of his connection with food, he was often enshrined in kitchens or dining rooms. In the Kyoto area, belief in Daikoku goes back at least to the Muromachi period (1336-1573)." (Quoted from: Dojo Magic and Exorcism Modern J: Magic and Exorcism in Modern Japan, by Winston Davis, Stanford University Press, 1982, p. 24.) |

||

|

|

||

|

Daimyō |

大名 だいみょう |

A feudal lord: literally it means 'great name'.

After certain daimyō were deified as incarnations of kami or gods they were also considered to be manifestations of buddhas. Unlike goryō who were malevolent spirits which had to be appeased and mollified daimyos were benevolent and were worshipped for that power despite their histories of military prowess. (See our entry on goryō on our Ges thru Haimyō page.) Tokugawa Ieyasu was deified as Tōshō Daigongen and Toyotomi Hideyoshi as Hōkoku Daimyōjin. |

|

Daimyō gyōretsu |

大名行列 だいみょうぎょうれつ |

Daimyō's procession - In an effort to maintain control over all of the various lords of Japanese fiefdoms the Tokugawa shogunate required that each daimyō maintain a residence in Edo, the shogun's capital, and that each daimyō leave important family members, wives and sons, there and visit them every other year for an extended length of time. This required great effort and expense on the part of these local rulers and each tried to outdo their peers in pomp and regalia. While these processions may have impressed other daimyōs and the people along the route they effectively disrupted these lords abilities to rule their own properties firmly and consistently and it upset their own financial stability to such an extent that it strengthened the central controls instituted by the Tokugawa regime.

Above is an Eisen triptych from the Lyon Collection. It is a mitate of a damiyo's procession. For more information click on it. |

|

Dai-Nippon Rokujuyo-shu no Uchi |

大日本六十余州内 だいにっぽん. ろくじゅうよしゅう.の.うち |

A series of prints by Kuniyoshi: "Sixty Odd Provinces of Japan - Dramatic Chapters" 1 |

|

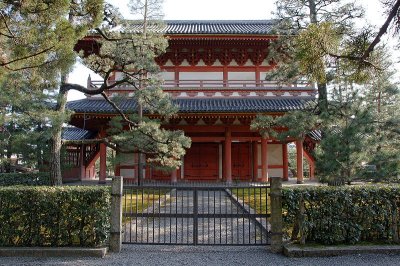

Daitoku-ji |

大徳寺

だいとくじ |

Buddhist temple of the Rinzai (臨済宗) Zen sect in Kyōto 1

The image shown above was posted at commons. wikimedia by 663highland.

The image to the left of the stone garden, the Daisen-in, is only one found at the Daitoku-ji. This photo posted by Ivanoff can also be found at commons.wikimedia. |

|

One story says that a statue of Sen no Rikyū (千利休: 1522-91), the great tea master, was erected near a gate of Daitoku-ji. This so infuriated Hideyoshi because he had funded that gate that he ordered Rikyū to commit suicide.

Ikkyū (一休: 1394-1481) served as an abbot here.

In a 1903 guide to Kyōto it states that the Daitoku-ji "...occupies a site of 57 acres in Ōmiya village, northwest of the city. It was established in A. D. 1323 by Myōchō [妙超: 1282-1337], also known as Daitō-kokushi, with the support of the Emperor Godaigo, who ordained it 'The Unrivalled School of the Zen Sect,' and made it an Imperial temple of worship. The success of this temple in later years was largely due to the abbots in charge; the witty and clever Ikkyū in the 15th century and the learned Takuan in the 17th century being widely known."

The Daitoku-ji is a complex of 24 temples, monasteries and offices. |

||

|

|

||

|

Dango |

団子

だんご

|

Dumpling motif: At first glance the use of the sweet dumpling would seem to be a rather odd choice for a family crest or mon - especially for a warrior clan. However, John W. Dower notes that its origin has a rather gruesome source. Supposedly "...Oda Nobunaga [織田信長 - 1534-82], Japan's great sixteenth-century unifier...wished to see the severed heads of his enemies skewered like dumplings on a spit." (Quote from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 110)

Dumplings made of steamed or boiled rice. When served three to a skewer they are called kushi-dango (串団子). The kushi element, 串, means 'skewer'.

Dango are served along with tea for moon viewing, tsukimi (月見). These are never skewered. This is according to Chado The Way of Tea: A Japanese Tea Master's Almanac. (p. 461) "It is said that dango (dumpling) has its origin in Chinese cake, danki. Sugar is added to rice flour, kneaded, rounded into an appropriate size and steamed." This volume also quotes a poem by Beitoku: "Come on moon, dango is served at all 53 stages of the Tōkaidō.

Yoel Hoffmann in his Japanese Death Poems (published by Tuttle, 1996, p. 277) notes that "One occasion for eating dango is during the cherry-blossom [sic] season in the spring."

In Shunju New Japanese Cuisine: New Japanese Cuisine by Takashi Sugimoto, et al., (published by Tuttle, 2002, p. 88) dango are mixed with salt-preserved cherry blossoms and ground chrysanthemum leaves. They can be served hot or at room temperature.

There is a major Japanese born American ceramicist, Jun Kaneko, who has created enormous pieces he calls Dango because they are reminiscent of dumplings. Their size alone is remarkable. Some of these are more than 13 feet tall, weigh thousands of pounds and take over a year to dry before they are bisque-fired. I have watched this man's career for years, long before I had this web site, and have to tell you - I am truly impressed.

The photograph of Mitarashi dango was posted at Flikr by Isaac'licious. |

|

Dannoura no Tatakai (The Battle of Dannoura) |

壇ノ浦の戦

だんのうら.の.たたかい |

This is the battle on April 25, 1185 which put the final nail in the coffin of Taira hegemony. 1

"...Minamoto Yoritomo (1147–1199), Yoshitomo's son, rose up to challenge [Taira Kiyomori] in the Genpei War. A child at the time of the previous conflicts, Yoritomo had been spared from death by Kiyomori and sent into exile. When another disgruntled political figure, prince Mochihito (1151–1180), sent out the call of arms to topple Kiyomori, Yoritomo dutifully obeyed by galvanizing the support of warriors in eastern Japan. Kiyomori tried to suppress the outlaws as he had done earlier, but mid-way through the war he lost the support of the by then retired emperor Go-Shirakawa. In a shrewd shift of allegiances, Go-shirakawa backed the rebel Yoritomo and instructed him to restore peace. Between 1183 and 1185, Yoritomo's forces drove the taira away from Kyoto, eventually sending them fleeing into the sea at Dannoura, where many of them drowned." Quoted from: Authorizing the Shogunate: Ritual and Material Symbolism in the Literary Construction of Warrior Order by Vyjayanthi R. Selinger, pp. 3-4.

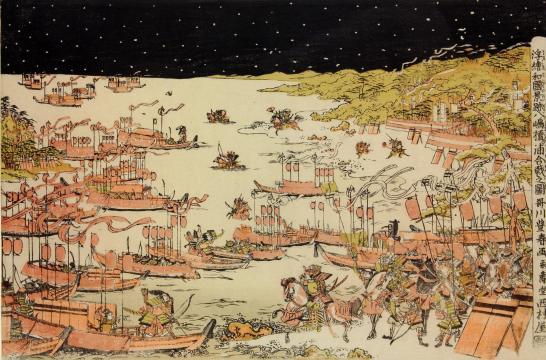

The image to the left is by Utagawa Toyoharu and is in the collection of the British Museum. |

|

Danshichi Kurobei |

団七力郎兵衛 だんしち.くろべえ |

Kabuki role of a man who slays his obnoxious father-in-law. |

|

Daruma |

達磨

だるま |

Daruma is the Japanese name for Bodhidharma who was the founder of what became known as Zen in Japan. 1

James T. Ulak in "Japanese Works in The Art Institute of Chicago: Five Recent Acquisitions" from 1993 noted that the Sanskrit Bodhidarma lived from c. 470 to c. 543 and was the 28th patriarch in a lineage from 'Sakyamini Buddha'. "Daruma was an Indian aristocrat who relinquished power and wealth in search of enlightenment." Ulak added that the Zen movement may owe some of its concepts to the yogic practices of India melded with certain Taoist practices from China. Daruma is often represented with long ear lobes stretch by the weight of heavy gold earrings and "...a long fingernail, on the thumb, which was the sign of an ascetic." Ulak added that the earliest known image of Daruma was from a Chinese book from the mid-11th c.

|

|

The word 'Daruma', for whatever reason, became a slang term for prostitute. According to one source there was a famous, beautiful courtesan in the late 1600s who laughed when she heard the story of Daruma sitting staring at a wall for nine years. She said basically "That's not such a big deal. Prostitutes have to spend every day and every night sitting and looking for customers - not facing a wall but facing the street through the windows. After ten years in this world of misery, I have already exceeded Daruma by one year."

Supposedly when the artist Hanabusa Itchō (英一蝶: 1652-1724) heard this anecdote he painted the first onna Daruma as a prostitute.

Sometimes Daruma is joined by one or more beautiful women. The conclusion: Even the most stolid, i.e., transcendental, male cannot avoid the lure of feminine wiles.

There are even cases where Daruma is shown dressed in drag. The reason? Got me. It must have amused someone. (See our entry for mitate. This might clear things up a bit - but don't count on it.)

Source and quotes: Daruma: The Founder of Zen in Japanese Art and Popular Culture, by H. Neill McFarland, Kodansha International, 1987, pp. 82-86.

F. Hadland Davis in his Myths and Legends of Japan (Kessinger Publishing, 2003, p. 298 - originally printed in 1912 or 1913) relates how Daruma fell asleep meditating before the wall. While sleeping he had a mildly erotic dream and when he woke "...he was truly penitent for the neglect of his devotions, and, taking a knife from his girdle, he cut off his eyelids and cast them upon the ground, saying: 'O Thou Perfectly Awakened!' The eye-lids were transformed into the tea-plant, from which was made a beverage which would repel slumber and allow good Buddhist priests to keep their vigils." It is also believed that his 9 years of meditation caused his legs to rot off leaving only a sort-of roly-poly figure. ¶ Davis adds: "He is sometimes presented in Japanese art as surrounded by cobwebs, and there is a very subtle variation of the saint portrayed as a female Daruma, which is nothing less than a playful jest against Japanese women, who could not be expected to remain silent for nine years!" (Ibid., p. 299)

Above is an illustration by Toyokuni I of Daruma riding a reed or blade of grass across the waters. We added the colors. Compare this to our entry on Hoso.

Stephen Heine in his Dōgen and the Kōan Tradition: A Tale of Two Shōbōgenzō Texts (SUNY Press, 1994, p. 197) realtes one of the versions of history of Daruma: "...referred to in the Hōrinden and later chronicles as the twenty-eighth Zen patriarch and the first on Chinese soil. Bodhidharma is depicted in the chronicles as the third son of a king who crossed the Yangtze on a single reed, meditated for nine years facing the wall of a cave till his legs withered away before gaining enlightenment, and commanded his foremost disciple to cut off his arm during a snowstorm as proof of his dedication. In some versions of the legend Bodhidharma is deified in that he performs supernatural feats, including conquering illness, poison and death. Tea is said to grow from the eyebrows he ripped off his face [see the variant version above] and discarded in disgust of himself for having dozed off during meditation."

In a follow up to the above entry we have The Complete Idiot's Guide to Understanding Buddhism by Gary Gach (published by Alpha Books, 2001, p. 203): "The legend was the Bodhidharma would only accept a student when the snows ran red. No takers, until one winter this guy named Hui K'o (Hwee Koh) cuts off his own arm and brings it to Bodhidharma as a token of his sincerity."

In A Buddhist Spectrum: Contributions to Buddhist-Christian Dialogue by Marco Pallis (published by World Wisdom, Inc, 2003, p. 85) the author recounts the tale of Bodhidharma who "on one occasion... came to the sea-shore wishing to cross to the other side. Finding no boat, he suddenly espied a piece of reed and promptly seized and launched it on the water; then, stepping boldly on its fragile stalk, he let himself be carried to the farther shore." ¶ Pallis in an esay in another book spoke about the trust it took to step on a reed with a sin-weighted body. (Pray Without Ceasing: The Way of the Invocation in World Religions, published by World Wisdom, Inc, 2006, p. 103). |

||

|

|

||

|

Date |

伊 だて |

A clan of the Sendai in Ōshű 1 |

|

Datehyōgo |

伊達兵庫 だてひょうこ |

A hairstyle popular in the 1790s. Worn only by the highest ranking courtesans. This style was represented in prints by Utamaro, Chōki and others.

Hairstyles were known by particular or specialized names just as a young American might go into a barbershop and ask for a flat-top or a crew cut.

The term 'date' (伊達) can mean elegance or sophistication, while 'hyōgo' (兵庫) may be eponymous for one of Japan's prefectures.

The image to the left is a detail taken from an unattributed print in the Lyon Collection. Click on it to see the whole image.

|

|

Date kurabe okuni kabuki |

伊達競阿國劇場 だてくらべおくにかぶき |

|

|

Date-sagari |

伊達下がり

だてさがり |

"Fashionable apron" - "......a kabuki costume element worn by footmen (yakko) in jidai mono and shosagoto. The actor ties it around the waist, where it hangs down in front like an apron. It has a gold and silver design with baren hanging from its bottom." Quoted from: Historical Dictionary of Japanese Traditional Theatre, p. 81.

The image to the left is from a Kunisada print from ca. 1818. Above is a date-sagari exhibited by Kogakkan University. |

|

Datsueba |

奪衣婆

だつえば |

The Old Hag of Hell who gathers the clothing or skins of the damned before they cross over the Three-Ford River (Sanzu no kawa - 三途の川) to Hell. 1

Datsueba is also referred to as Sōzu no baba. Another alternative is Shozuka no baba (脱衣婆) or the Old Woman Who Takes Off the Clothes. According to The Tale of the Fuji Cave Datsueba is a manifestation of the Dainichi Buddha. Of those wearing clothes she strip the dead of 25 robes "...in accord with their twenty-five types of sin." If they arrive naked she strips them of their skins and hangs them "...on the limbs of a biranju [毘蘭樹] tree" and later makes these into celestial feather gowns. The robes in question were generally the burial robes. The worse the sin the heavier the robe causing the branches to droop. |

|

"Datsueba is a deity worshipped by women at the uba-dō [うばど], a building reserved for women, and traditionally marking the limits of the nyonin kekkai [prohibition against women entering a sacred area: 女人結界]. Thus, during the autumn equinox (higan [彼岸]), a rite of passage for women known as the 'great unction... of the bridge covered with pieces of cloth' (nunobashi [布橋] daikanjō-e) was performed at the Uba-dō at Tateyama [立山]. Three bands of white cloth were spread on the path leading to the Yama Hall (Enma-dō) to the Uba-dō, crossing a stream on a bridge. This cloth, offered by the believers, was later used to fabricate clothes for the dead, so that they could appear in front of Datsueba wearing consecrated clothes, thus avoiding having their skin taken off by the terrible old hag. The stream is symbolically associated with the Sanzu no kawa, while entering the Uba-dō is interpreted as 'entering the Pure Land' (jōdo-iri [浄土 入り])." After three days of chanting for salvation the officials would throw open the gates and the women would sense a vision of the Pure Land Paradise. Quoted from: The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender, by Bernard Faure, published by Princeton University Press, 2003, p. 315.

Uba-dō and Tateyama explained: "...at the foot of Tateyama, there is a small building called Uba-dō, dedicated to the mother of Jikō Shōnin [時光上人]. Interestingly, she has become identified with a rather frightful female deity - although she is represented here with a smiling face - the old infernal hag known as Datsueba..." (Ibid., p. 232) In 1869, they year after the Meiji Restoration, the prohibition against allowing women to climb Mt. Tate was lifted, but "...it was a pyrrhic victory for women: the Uba-dō was destroyed in the process, the cult of Datsueba forbidden, and the place turned into a cultic center of 'pure' Shintō. Yet the old associations were resilient, and the place has recently experienced a revival of sorts." (Ibid., pp. 232-3)

By the time of the Edo period Datsueba had been syncretized fully with the Japanese concepts surrounding the uba. She was often shown in the company of Emma-O the King of Hell. At Asakusa-dera is a statue of an uba that people prayed to is they are suffering from a toothache. In another location people with severe coughs pray to a statue of Datsueba. "In other cases, Datsueba has become a protector of children, and women prayer for her boons such as abundant lactation and children's health. In this function, she appears to be an avatar of the uba-gami. In some variants of the legend, the clothes (or the skin) that she tears off from the dead as they are about to enter hell are metaphorically assimilated to the placenta that she gave them at birth." (Ibid., pp. 315-316)

Stephen F. Teiser in his The Scripture on the Ten Kings and the Making of Purgatory in Medieval Chinese Buddhism (University of Hawaii Press, 2003, p. 31) "The producers of books and the preachers responsible for educating lay people about the fate of the dead understood well that the displaying of pictures of bodies in pain tends to have a more significant impact than simply writing or talking about them." In other words, a picture is worth... ¶ A British Museum web page notes that the Ten Kings of Hell are based on an apocryphal sutra dated 903 A.D. They rule over the successive spheres through which the soul must go to attain rebirth. The soul first appears before the first seven kings at seven day intervals, the 8th king after 100 days, the 9th after a year and the 10th on the 3rd anniversary of their death. Teiser continues (p. 33): "Movement toward a fate measured by gradations of karma is shown especially clearly in some of the illustrations of the second court, administered by the King of the First River. In the second week after death, the spirit must cross the River Nai." Some will nearly drown, others will cross at the shallows, while those least cursed by the weight of negative karma may cross over a bridge. "The Japanese text refines the spiritual ranking by specifying that people can cross the river at three fords: at the shallows of a mountain stream, at a deep river, or by a bridge. The Japanese text also makes sense of the imagery in other versions of this scene... in which sinner's clothes hang from a tree on the banks of the river. The tree is actually a scale, says the Japanese text, that measures the worth of people's past actions. The text also names two figures missing from the Chinese illustrations, Datsueba (Old Woman Who Pulls Off Clothing) and Den'eo (Old Man Who Hangs Up Clothing), whose jobs explain how the tree-scale comes to function." This obviously is the source of the Japanese concept of the Three-Ford River. |

||

|

|

||

|

Dayflower (Tsuyukusa) |

露草 つゆくさ |

Source of aigami, an early organic blue colorant which fades easily. 1

On 9/3/14 we added this photo which had been posted at Flickr by t-mizo. |

|

Years ago I moved into a run down house in Kansas. The front yard was covered with tiny blue flowers amid rich green leaves. I thought these beautiful, but my new neighbor to the east informed me that these were nothing more than pernicious weeds. I liked them anyway and remember crushing some of the petals between my fingers. It made a slightly bluish color which was easily washed off. This was the dayflower or spiderwort. (Dayflowers are members of the spiderwort family.) I had no idea at the time that the dayflower in my front yard was the same source as that of the washed out colors I was looking at in late 18th century Japanese prints.

I didn't think about these flowers much - it has been about twenty years since I lived there - until recently when I was reading about Japanese kimonos and the yūzen technique in particular. Yūzen (友禅 or ゆうぜん) is a type of fabric design created with a rice paste resist method of painting or dyeing.

The dayflower's dyes are impermanent and hence are referred to as 'fugitive'. Extremely fugitive would be more accurate. They fade when exposed to light - maybe even when they aren't. They can be washed out fairly easily too. That is why they are used by yūzen masters in creating the designs for their fabrics.

Originally a length of silk would be stretched taut and then a light blue design outline would be painted in freehand with aobana (青花 ) which is the dye made from the dayflower. [It is referred to as aigami (藍紙) when used as a dye on early ukiyo-e.] Outside of the pale blue line a thin rice paste resist line was then added. According to one web site a diluted liquid from beans can be washed onto the back of the cloth to remove the aobana lines. Other than that it would disappear with an extended steaming process which would remove the rice paste and set the painted colors.

According to Amanda Mayer Stinchecum in Kosode: 16th-19th Century Textiles from the Nomura Collection (published by the Japan Society and Kodansha International, 1984, pp. 202-3) "Juice of the petals contains delphinidin and can be extracted with the morning dew in May and June." In the Nara period [710 to 794 A.D.] fabrics were rubbed with the petals. "During Edo [1615 to 1868 A.D.], liquid used to outline yūzen designs for dyeing, outline washed out after dyeing."