Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

U thru Yakko |

|

|

The molecular model on Lonsdaleite is being used as a marker for new additions from January 1 to May 31, 2021. The piece of sulphur posted at Wikimedia by Rob Lavinsky was used from June 1 thru December 31, 2020.

The detail from the diadem of

the Empress Eugénie |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Ubume, Uchide no kozuchi, Uchiwa, Udon noodles, Uirō, Ukai,

Ukiyo-e prints, Umajirushi, Uma,

Umakazari,

Umazumi jigoku, Ume, Umeki, Umewaka Shrine, Umi-bozu, Umin, Unbo, Urashima Tarō, Urauchi, Uri, Uroko, Usagi, Ushi no yodare, Ushi oni, Ushirometai, Ushiwakamaru, Utagawa Hirosada, Utagawa Hiroshige II, Utagawa Kunisada, Utagawa Kuniyoshi, Utagawa Toyokuni I,

Utagawa Yoshikazu,

Rudolph Valentino, Wachigai, Waka,

Wani, Wanko soba, Waraji, Washi, James McNeill Whistler, Willow Pattern, Worcester, The World of the Meiji Print: Impressions of a New Civilization, Ya, Yabusame, Yagasuri, Yagō, Yagura,Yajirobei, Yakara no tama and Yakata-bune, Yakko

産女, 打ち出の小槌, 団扇, 饂飩, 外郎, 鵜飼い, 浮絵, 浮世絵版画, 馬

馬印, 馬飾り,

海坊主, 羽民, 雲母, 国連総会, 浦島太郎, 裏打, 瓜, 鱗, 兎, 牛の涎, 牛鬼, 後ろめたい, 牛若丸, 歌川広貞, 二代広重, 歌川国貞, 歌川国芳,

歌川豊国, 歌川芳員,

嫐, 後妻打ち, 輪違, 和歌,

椀子蕎麦,

蕨, 草鞋, 和紙, 矢, 流鏑馬, 矢絣,

櫓, 彌次郎兵衛,

|

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

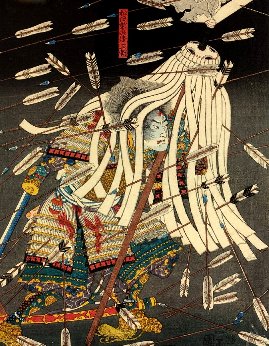

Ubume |

産女

うぶめ |

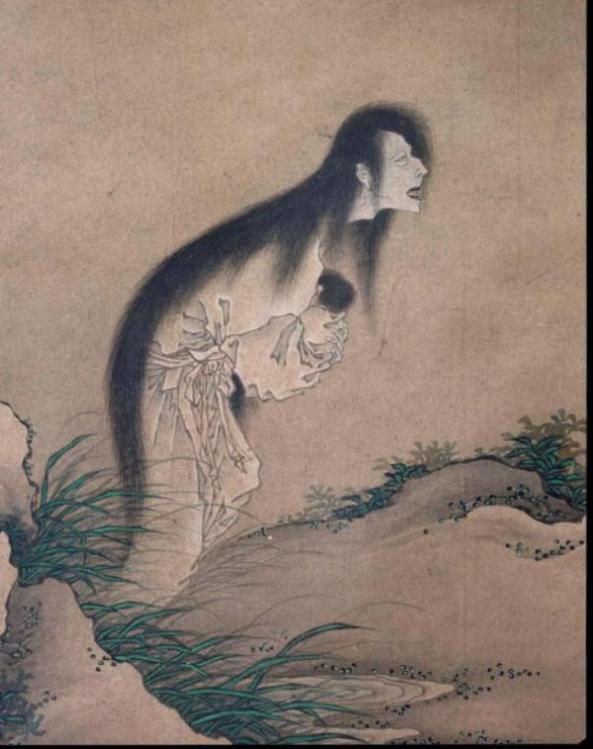

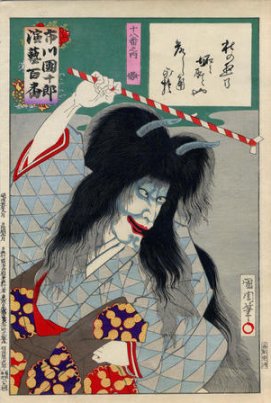

A 'birthing woman ghost' - "These female ghosts, who generally appear holding babies, embody both the sufferings of women who died during pregnancy or childbirth and the love and concern of the dead mothers for the babies they left behind, or took with them." Quoted from: 'The End of the “World”: Tsuruya Nanboku IV’s Female Ghosts and Late-Tokugawa Kabuki' by Sataoko Shimazaki in the Monumenta Japonica 66/2, p. 213.

The images shown here come from the collections of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and Ritsumeikan University. The one to the left is from an 1865 Yoshitoshi print at Ritsumeikan and the one above is a detail from a Hokusai painting in Boston. |

|

"The earliest known account of the ghost of a woman holding her baby in her arms—a distant ancestor of Nanboku’s ubume—occurs in the story “Yorimitsu no rōdō Taira no Suetake ubume ni au koto” 頼光郎等平季武値産女語 (How Yorimitsu’s Attendant Taira no Suetake Encountered an Ubume) in the early twelfth-century collection Konjaku monogatarishū 今昔物語集. In this tale, a group of men discuss a certain frightening ubume who has been appearing in a place called Watari 渡. One of the men, Taira no Suetake 平季武, goes off on a dare to cross the river at Watari. As he makes his way across, a strange woman appears and asks him to hold her crying infant. The woman is not described in visual terms: her words are simply overheard by three of the other men from the group who were brave enough to follow Suetake and hide behind a bush as he crossed the river, and we are told that her appearance was accompanied by a terrible stench. The narrative concludes with an extremely ambiguous note by the compiler: “Some people say this ubume was a fox playing a trick on a human, others say it was a woman who turned into a spirit (ryō) when she died before being able to give birth to her baby girl. That, they say, is the story that has been passed down.” (Ibid., pp. 214-215)

Sometimes the ubume is represented as a bird or even as a single wing

with long, flowing black hair like the ubume seen in the painting

shown above on the right. Shimazaki tells us that in the "Kokon

hyakumonogatari hyōban 古今百物語評判 (An Analysis of a Hundred Ghost Stories

Old and New, 1686).... based on a manuscript by Yamaoka Genrin 山岡元隣

(1631–1672), offers a Neo-Confucian

"In China, the ubume is called guhuoniao or yexing younü 夜行遊女 [Jp. yakō yūjo; literally, “night-wandering woman”]. Xuanzhong ji 玄中記 (Record of Mysterious Creatures) says that this bird is a type of evil deity. When it puts on feathers, it turns into a bird; when it takes the feathers off, it turns into a woman. This is what happens after the death of women in childbirth. For this reason, the bird has breasts and takes pleasure in snatching people’s children and making them its own. You should never hang children’s clothes outside because then the bird drops blood on one of them as a mark, and the child develops convulsions. This bird is seen a lot in Jingzhou 荆州 province. In addition, Bencao gangmu says that there are no male ubume and that they often appear at night in the seventh or eighth month to inflict harm.… Originally this creature must have emerged spontaneously from the corpse of a pregnant woman, and then later others of the same sort were born. Since it originated from the qi 気 [energy] of the pregnant woman, it acts on that nature." (Ibid., p. 222)

Below is the right-hand page from an ehon, Bakin’s Bei Bei kyōdan 皿皿郷談 (A Country Tale of Two Sisters, 1815) illustrated by Hokusai. It shows a bird/ubume giving her child off to a man. There is an ink mark obscuring the face of the man. It is from the collection of the Waseda Library. Note how this creature hovers over a nagare kanjō.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Uchide no kozuchi |

打ち出の小槌

うちでのこづち |

The magic mallet carried by Daikoku, one of the Seven Propitious Gods.

"A popular theme in folklore, the special mallet called uchide no kozuchi would produce fortune when struck. The fortune that Daikoku produces with his mallet is rice as iconographically represented by the bundle of rice (komedawara) upon which he places his foot."

Quoted from: Rice as Self: Japanese Identities Through Time, by Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 66

See our Daikoku

entry to read about the significance of the mouse. "Daikoku's attribute, a Rat, has an emblematic and moral meaning in connection with the wealth hidden in the God's bag. The Rat frequently portrayed in the bale of rice with its head peeping out, or in it, or playing with the Mallet, and sometimes a large number of rats are shown. [¶] According to a certain old legend, the Buddhist Gods grew jealous of Daikoku. They consulted together, and finally decided they would get rid of [him]..." Emma-O, the King of Hell, sent his most clever devil to conquer Daikoku. When the demon confronted the God of Wealth Daikoku called his rat to him. "When the Rat saw [the demon] he ran into the garden and brought back a branch of holly, with which he drove the oni away, and Daikoku remains to this day one of the most popular of the Japanese Gods. This incident is said to be the origin of the New Year's Eve charm, consisting of a holly leaf and a skewer, or a sprig of holly fixed in the lintel of the door of a house to prevent the return of the oni.

Source and quote from: Myths and Legends of Japan, by F. Hadland Davis and Evelyn Paul, published by Courier Dover Publications, 1992 (originally published in 1913), pp. 211-212. |

|

Uchiwa |

団扇

うちわ

|

"For the Japanese, fans are not merely for fanning...but they are quite indispensable in ceremonial, social and daily activities throughout the year.... Almost all races have had their fans...but nowhere else in the world have fans become such articles of necessity and utility in Japan."

The uchiwa, a flat fan, is one of two types of Japanese fans. The other is the ogi or folding fan.

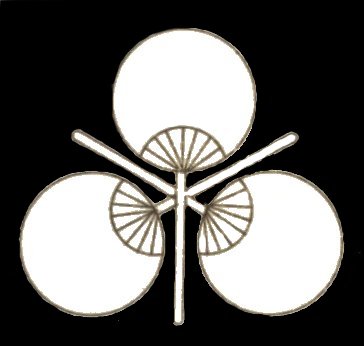

The top image to the left by Kuniyoshi is an example of a print made especially to be cut out and pasted down to the stiff panel of the uchiwa. This print was sent to us courtesy of E., our most generous contributor. The image below that is only one example of the use of a fan as a family crest or mon.

preference used by women. It is never part of one's 'dress'. It does not belong to one person in particular. It is the fan of the household, belongs to the group."

According to Casal the most popular form still used today, the Edo uchiwa (江戸団扇), was invented in 1624 by an unknown genius who realized that if you split a piece of bamboo from the node outward it would form ribs which would support paper or other materials creating a sturdy and practical fan. |

|

U. A. Casal in his "Lore of the Japanese Fan" (Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 16, no. 1/2, 1960, p. 64) notes that "The Japanese word uchiwa, for the stiff roundish fan, is evidently a corruption of utsu-ha [うつは?], the 'striking (or swatting) leaf.'" He adds that "Even today women and children use uchiwa to catch fireflies, the fan being sometimes attached to a bamboo for greater reach."

Uchiwa are also referred to as dansen (団扇). Note the kanji characters are the same.

Casal (p. 66): "The uchiwa became the fan of the home. Always ready at hand in summer, the first thing offered to a guest when he calls.... It never developed into a ceremonious fan, and was by preference used by women. It is never part of one's 'dress'. It does not belong to one person in particular. It is the fan of the household, belongs to the group."

According to Casal the most popular form still used today, the Edo uchiwa (江戸団扇), was invented in 1624 by an unknown genius who realized that if you split a piece of bamboo from the node outward it would form ribs which would support paper or other materials creating a sturdy and practical fan.

The Fukui district (福井県) produced uchiwa covered with paper treated with persimmon juice making them waterproof. They could then be dipped in water and fanned for greater relief in the hottest weather. These are called kaki-uchiwa (柿団扇). Some believed that just using persimmon treated fans could keep the god of poverty, Bimbō-gami (貧乏神), at bay. (Casal - p. 68)

Prior to modernization some firemen would climb to rooftops at some distance from a fire and would use oversized uchiwa at the fire being fought. It was meant to symbolically drive away the evil flames. (C. - p. 69)

Men would use uchiwa, but only in private. (C. - p. 70) |

||

|

|

||

|

Udon noodles |

饂飩

うどん |

In Mock Joya's Things Japanese (p. 56) there is a lament that an old method for curing colds had died out. "To make the bath cure more effective, [in] many public bathhouses.... there was a custom of ordering udon (hot wheat noodle soup) or soba (buckwheat noodles in hot soup) from neighboring noodle houses and eating it while comfortably bathing in the hot tub. Up to the middle of the Meiji ear, this custom was very popular in various cities and towns. Enjoying the warmth of the hot tub, one can leisurely eat a steaming bowl of udon or soba. The noodles taste particularly good, as the eater is in a pleasant turn of mind brought about by the warm bath. It cures the cold, but at the same time, it is liable to create a habit. Whether one has a cold or not, whenever he goes to the bathhouse, he is tempted to order a bowl of udon." 1

"Most soba restaurants serve another noodle called udon. Udon is a thick and pasty wheat noodle which is somewhat blander than soba. It is served hot (as kake-udon) with the same choice of topping ingredients as soba. In the Kansai region (around Osaka and Kyoto), udon is much more popular than soba, but in Tokyo soba is the favorite."

Quote from: What's What in Japanese Restaurants, by Robb Satterwhite, Kodansha International, 1996, p. 71

"A primitive form of udon, used to make stuffed dumplings, was introduced from China in the early centuries of the first millennium. By the Muromachi Era (1338 to 1573), udon noodles appeared, but they were mainly consumed at temples. Udon finally reached the commoners during the Edo Era (1600 to 1868). Unlike soba noodles, udon gained more popularity in the Kansai region, which includes Osaka, Kyoto, and the surrounding area."

Quote from: The Japanese Kitchen, by Hiroko Shimbo, Harvard Common Press, 2000, p. 155.

"Unlike soba noodles, udon noodles are simple and easy to make from scratch..." (Ibid., p. 156) "...salt is not used to flavor the noodles, but works chemically on the wheat protein to create a plastic elasticity. This prevents the noodles from breaking during storing and cooking." (Ibid., p. 157)

The image to the left has been placed in the public domain by Ranveig at http://commons.wikimedia.org/. |

|

Uirō |

外郎

ういろう |

A sweet made from rice powder. However, this product was also sold as a cure-all "...a kind of panacea used as an expectorant, deodorant, and mouthwash (among other things)." We mention this because Danjūrō II created in 1718 the character of a peddler carrying a large chest on his back which holds his wares.

The image to the left is from a karuta deck of eighteen cards each representing one of the kabuki jūhachiban or the eighteen plays that became the standard vehicle of the Ichikawa family of actors.

There is an ancient universality to the tradition of snake oil salesmen preying on people searching for a panacea. While most bogus potions were rarely toxic, whether applied externally or ingested, their greatest efficacy would probably be scratched up to 'the placebo effect'.

The battle between the two camps best represented today by alternative medicine advocates on the one hand and the FDA on the other leave most of us puzzling over the proper course of action. Yet there seems to be no silver bullet although at times things like penicillin and MSG were thought to be damned close. But people keep hoping. Conclusion: As long as there are snake oil or uirō salesmen there will be a public gullible enough to buy from them. |

|

Ukai |

鵜飼い

うかい

|

Cormorants (鵜 or う) are long necked, diving birds known for their voracious appetites. (The OED says that the word 'cormorant' can be used figuratively to describe a greedy, rapacious person.) Ukai is cormorant fishing.

The birds are captured and trained to dive on command to 'fetch' fish. A group of cormorants are tethered by a handler who pulls the birds in to remove their catch. To prevent the birds from swallowing the fish there are rings placed around their necks.

The picture of the cormorant fisherman stamp was posted by Carpazu at commons.wikimedia.org. The photo of the fisherman shown above was posted by Hide-sp at the same place as was the cut out image below. |

|

This is an ancient East Asian technique not unique to Japan. While this system has been practiced on various rivers the most famous local is on the Nagara River in Gifu. Often these fishermen came under the protection of local lords, but the one on Nagaragawa was patronized by the Imperial Court. Their cormorants are trained to catch ayu (鮎 or あゆ), sweetfish or freshwater trout, which are then sent onto the Court for their pleasure.

Cormorants and god-related cormorants are mentioned several times in the Kojiki (古事記) which is the oldest known Japanese text. (Source: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 155)

There is a Shunshō print in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago portraying an actor in a female role as a cormorant fisherman standing on shore beside the boat holding a torch. This print dates from ca. 1771-2 and is the earliest example I have seen so far. If you know of an earlier one please contact me.

Basil Hall Chamberlain notes in his Things Japanese: "This strange method of fishing is mentioned in a poem found in the Kojiki, a work compiled in A.D. 712, while the poem itself probably dates from a far earlier age." In his introduction to his translation of the Kojiki Chamberlain states: "The horse (which was ridden, but not driven, the barn-door fowl, and the cormorant used for fishing, are the only domesticated creatures mentioned n the earlier traditions, with the doubtful exception of the silkworm..." (p. xlii-xliii) Again, back to his Things Japanese Chamberlain quotes a Major General Palmer in a letter to the Times [of London?]: "Round the body is a cord, having attached to it at the middle of the back a short strip of stiffish whalebone, by which the great awkward bird may be conveniently lowered into the water or lifted out when at work; and to this whalebone is looped a thin rein of spruce fiber, twelve feet long, and so far wanting in pliancy as to minimize the chance of entanglement. When the fishing ground is reached the master lowers his twelve birds one by one into the stream and gathers their reins into his left hand, manipulating the latter thereafter with his right as the occasion requires." The master has to have a keen eye and keep track of everything that is happening. He will know when a bird has caught its fish when it "...swims about in a foolish, helpless way, with its head and swollen neck erect." The fisherman then pulls the bird to him and pries its beak open with his left hand while still controlling the reins of all of the others at the same time. He then squeezes out the fish with his right hand and returns the bird to the water. As for the birds: They are captured when quite young, coddled through life - with the exception of this exercise - and can be productive for up to 15 to 20 years - their hunting taking place only during a five month season. As with other creatures there is a pecking order. The oldest, the leader, is placed in the water last, is the first to be pulled out, is fed first and is put in a cage that is placed honorifically at the bow. Palmer states of this bird: "He is a solemn, grizzled old fellow, with a pompous, noli me tangere air that is almost worthy of a Lord Mayor." (pp. 95-98)

"...Buddhists condemned the killing of fishes and birds by anglers and hunters as a criminal activity no less sinful and defiling than manslaughter.... The association established by Buddhist monks between the practice of fishing with the help of a cormorant and a maturation of a negative destiny (karma) leading to a rebirth in hell is the topic of an eleventh century poem addressed to coastal villagers:

How wretched for me to be a cormorant fisher! I kill the ten-thousand-kalpas-old tortoise, And tie the cormorants neck. Somehow I will manage to go on with this life, But what will become of me in the next?

(Quotes from: Representations of Power: The Literary Politics of Medieval Japan by Michael F. Marra, p. 83) |

||

|

|

||

|

Uki-e |

浮絵

うきえ

|

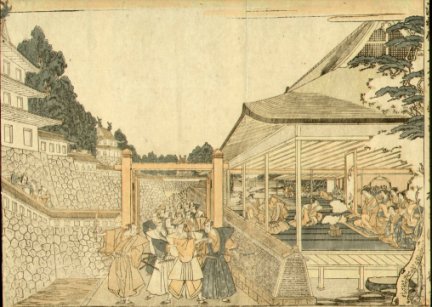

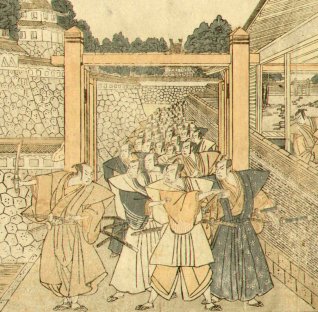

Basically a perspective print created in imitation of the European principles of recession.

"The studies of Julian Lee have shown that Japanese artists did not learn the methods of western perspective form studying western prints, but via an illustrated Chinese translation of a European treatise on perspective which was published in Canton in the early 1730s and found its way to Edo by 1739, the date of the first large perspective print, an interior of a kabuki theater designed by the artist Torii Kiyotada."

Quoted from: Japanese Woodblock Prints : A Catalogue of the Mary A. Ainsworth Collection, by Roger Keyes, Oberlin College, 1984, p. 94.

The images to the left are by Masayoshi and date from ca. 1780 illustrating a scene from the Chūshingura. This example was sent to us by our generous contributor E. Thanks E! |

|

Ukiyo |

浮世 うきよ |

Ivan Morris in his notes to his translation of Ihara Saikaku's The Life of an Amorous Woman and Other Writings gives various meanings to the term ukiyo on page 293, fn. 10: "Ukiyo (floating world) was the conventional image used by writers, both lay and clerical, to convey the transitoriness of present life; in Saikaku's time it also suggested the fugitive pleasures of the demimonde; hence ukiyo-e, the genre paintings. By further extension, ukiyo meant 'fashionable,' 'up-to-date,' as in ukiyo-motoyui (fashionable type of paper cord for tying the hair). It also had the sense of 'depraved' as in ukiyo-dera (the temple of a depraved priest)."

"Ukiyo had originally signified the Buddhistic 'sad world' of change and decay, but later it came to mean the 'floating world' of pleasure and fashion, whose heroes were the actors and the courtesan and whose guiding principles (according to a well-known saying) love and money."

|

|

Ukiyo-e prints |

浮世絵版画 うきよえ.はんがん |

Donald Jenkins wrote: "This might be the place to explain for those less familiar with ukiyo-e prints that the artists whose signatures appear on them had no hand in the physical production of the prints. Their role was to provide the designs, usually at the behest of the publisher. The carving of the blocks was entrusted to specialized engravers, and the printing was the responsibility of yet another group of specialized craftsmen.... The role of the publisher was akin in many ways to that of the producer of the modern film."

|

|

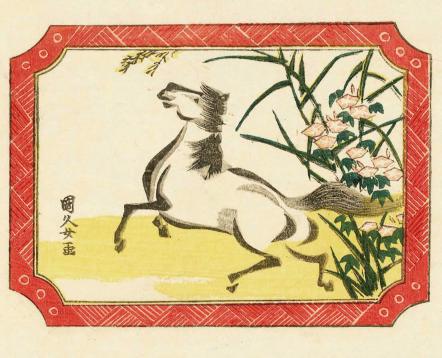

Uma |

馬 うま |

Horse - one of the signs of the Zodiac. Of course, the horse as a creature played a different role in Japanese history. "It is little wonder that, once Japanese fighters learned equestrian skills, the horse was used almost exclusively for war; and gradually came to dominate war strategy until the fourteenth century and the appearance of a pike-bearing (yari) peasant infantry. ¶ The cavalry revolution originated in the Middle East about 900 B.C. and had several implications. First making war from a galloping horse was a dangerous occupation. In order to be effective, the warrior on horseback needed both hands free to wield a weapon; yet letting go of the reins seemed to guarantee that the fighter would end upon the ground, bruised and helpless. The only alternative was t guide the horse with one's feet and legs, perhaps using the voice to direct a trained horse. Training both horse and rider took time and practice. ¶ Moreover, a horse was expensive, and not everyone had the leisure time to practice. A horse could consume as much grain as 6 to 8 persons, and the owner was responsible for mating and training the animal. Furthermore, the horse was not very useful aside from its war-making capacities: Its meat and milk could not compare to the cow's, and it could not pull a plow until the Europeans invented the horse collar about A.D. 1000. Therefore, civilized societies that utilized the horse extensively tended to have specialized fighters. In some cases, the warriors might be aristocrats, in others, slaves; but always the big question was how to pay for such and expensive military system." Quoted from: Heavenly Warriors: The Evolution of Japan's Military 500-1300 by William Wayne Farris, p. 15.

The image to the left is a small detail from a Toyokuni II print in the Lyon Collection. This s horse was drawn by Kunihisa. Click on it to see the full print. |

|

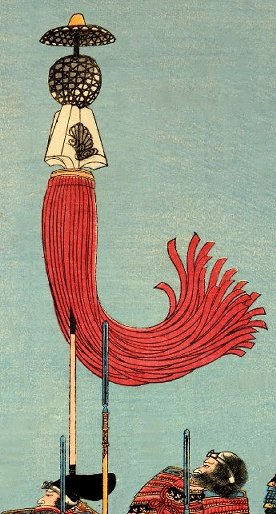

Umajirushi |

馬印

うまじるし |

A commander's battle standard - literally it means 'horse' plus 'emblem'. "Only the bravest men acted as standard bearers..." according to Stephen Turnbull.

"Many objects appeared as uma-jirushi. Oda Nobunaga sported a colossal red umbrella. Toyotomi Hideyoshi used a large wooden gourd painted gold. He is supposed to have added a gourd for every victory he won, until by the time of his death the standard was known as the 'thousand gourd' - metaphorically if not literally." Quoted from: Samurai Armies 1550-1615 by Stephen Turnbull, 1979, p. 37.

|

|

Umakazari |

馬飾り うまかざり |

Caparison - |

|

|

馬尻尾

うまのしっぽ |

A horse tail or the name of a kabuki wig, a pony tail -

Above is a detail from a Hokusai print from the collection of the British Museum.

To the left is a detail from a Hokushū triptych in the Lyon Collection. It show Sawamura Kunitarō II as the akuba or 'evil woman' wearing a wig with a pony tail. |

|

Umazumi jigoku |

不産女地獄 うまずめじごく |

Hell for childless women |

|

Ume |

梅

うめ

|

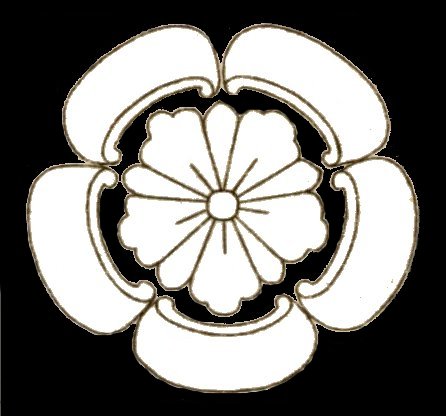

Plum blossom - This is one of most commonly used motifs for crests, i.e., mon.

Merrily Baird in her Symbols of Japan (pp. 64-65) tells us that while 'ume' is usually translated as plum it is in fact apricot. Imported from China by the 8th century it was the most frequently mentioned flower in Japanese poetry because of its qualities: A sweet perfume, delicate blossoms and because it bloomed early and endured while it was still cold enough to snow. When joined with the bamboo and the pine we have what are known as The Three Friends of Winter.

The graphic shown to the left is only one example of the 'ume' as a family crest. Baird notes that "...a guide compiled by the Matsuya Piece-Goods Store included eighty crests based on the plum blossom."

"The Song poet Lin Bu (967-1028), who is said to have surrounded himself with plum blossoms and cranes in his hermitage.... Ever since the time of Lin Bu, the cold of winter and plum blossoms blooming in the snow are considered the symbol of moral integrity and self-chosen reclusion removed from the bustle of this world, an ideal to which the Zen masters felt a deep affinity in their search for hte pure void and enlightenment." (Quote from: Zen: Masters of Meditation in Images and Writings, by Helmut Brinker and Hiroshi Kanazawa, Artibus Asiae Publishers, 1996, p. 178)

In the 15th century a Zen abbot wrote: "...spring awakening is close. / The trees do not have leaves yet; they stand amidst the melting snow. / Anticipating the [plum] blossoms is like awaiting elegant guests." (Ibid., p. 195)

Alfred Koehn stated in his Japanese Flower Symbolism published by Lotus Court in 1939 "The Japanese see the contrast between the knotted trunks and young green shoots as symbolic of age and youth - one bent and crabbed, the other fresh and vigorous, suggesting that in spite of age, the charm and joy of youth can always rise anew."

Koehn in his article Chinese Flower Symbolism in the Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 8, No. 1/2, 1952, p. 127 added that "Female Chastity, also, is symbolized by the flowers on leafless branches."

According to Mock Joya the ume's position as the most beloved flower in Japan was usurped in time by the sakura or cherry blossom: "Having come to be considered as the foremost flower of the country, sakura came to be referred to as 'hana' (flower). But there was a time when 'hana' stood for ume (apricot) blossoms, as they were loved above all other flowers soon after their introduction from China.

It is not clearly known when sakura came to replace ume, but it seems that the aristocracy first came to admire sakura in the Heian period (794-1192). The Manyoshu, the oldest collection of poems which contains poems written between 315 and 759, contains no poem on sakura, but in this collection, ume has 113 poems." (Quoted from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 369)

"The plant and blossoms are now generally called ume but formerly the name was pronounced 'mume.' " (Ibid., p. 377)

"Cherry-viewing parties are merry, but ume parties are quiet and dignified. Probably that is the reason why the younger people have no interest in visiting ume gardens." (Ibid., pp. 377-8)

The photos to the left are being shown courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. |

|

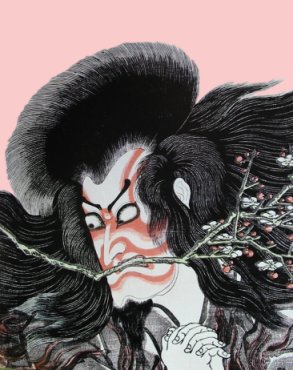

The historical figure Sugawara Michizane (菅原道真 or すがわらみちざね) who was declared the god of calligraphy and scholarship, is often associated with plum blossoms. Temples devoted to this deity known as Tenjin (天神) plant ume trees on their grounds. The detail of a print by Kunisada shown below portrays the actor Ichikawa Danjūrō VII as Kan Shōjō.

"Kan Shōjō, in fact, represents Sugawara Michizane (845-903)... since government regulations prohibited the use of names of real people in kabuki." Learning of his banishment from court Kan Shōjō transforms himself into the god of thunder. A branch of plum blossoms can be seen held between his clenched teeth. This "...motif [is] associated with Michizane, who before going into exile, had composed a poem to a plum tree in his garden, reminding it not to forget the arrival of spring after he was gone." (Source and quotes from: Kunisada's World, by Sebastian Izzard, Japan Society, Inc., 1993, p. 50)

Michizane was portrayed occasionally in print form riding atop an ox. Hence, if an ox is shown accompanied by plum blossoms that is a substitution for Michizane himself.

Michizane "...was fond of ume flowers from childhood, and it was for a poem on the flower written when he was 11 years old that he was first recognized by the emperor. When he was finally exiled, after a most brilliant career at Court, he wrote the following famous poem:

Kochi, fukaba nioi okoseyo ume-no hana Aruji nashitote haru na wasureso

[こちふかば によひおこせよ うめのはな あるじなしとて はるなわすれそ]

When the east wind blows, Send your fragrance, Flower of Ume. Never forget spring Even though your master is gone.

Mock Joya, pp. 580-1 |

||

|

|

||

|

Umeki |

梅若 うめき |

In book publishing an umeki is a replacement block. "This method of production not only yielded a set of blocks which could be reused, but also, if for any reason the blocks were destroyed, an extant book could be cannibalised and used as the mast (by pasting and recarving) for a reprint. Block text also allowed corrections through 'planting' new wood where required in the block. This method (called umeki) was used to replace worn areas, make corrections, change names or update the publisher's details. There are stories of less scrupulous publishers using the technique to change the title on the block and sell the same book twice. " Quoted from: Japanese Popular Prints: From Votive Slips to Playing Cards by Rebecca Salter, pp. 44-45. |

|

"The other technique that was widely used for a variety of purposes was umeki 埋木, the replacement of part of a printing block with a fresh piece of wood containing a different text. This was used for many purposes in the Tokugawa period. Firstly, it was used to correct textual errors that occurred when the hanshita was being prepared by the copyist or when the blocks were being carved: it is not clear to what extent proofreading of printed texts was carried out before publication in the Tokugawa period, but the survival of some corrected proofs from the late eighteenth century shows that it was at least carried out for some of the more substantial genres of fiction from that time, both to correct errors, and to make emendations for avoidance of censorship problems. Umeki was also used to replace worn or broken parts of the blocks, and very frequently to alter the colophon for a later reprint by changing the date and/or the name of the publishers. It was also used to change the name of actors in publications related to the theatre, or the names of prominent officials named on maps or in directories... More alarmingly, it was also used by somewhat unscrupulous publishers to alter the title of a work that would then be presented as if a new and entirely different work. And finally, it was used to make minor alterations to illustrations for reasons that are often obscure. For all these reasons it is rarely safe to assume that apparently identical books do indeed carry an identical text, although few reprints pay any attention to these textual variations and facsimile editions are rarely sufficient to make detection of umeki alterations easy." Quoted from: The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth Century by Peter Kornicki, pp. 52 & 54. |

||

|

|

||

|

Umewaka |

羽民

うめわか |

In one of the versions of this story, in 976 a young boy, Umewaka, wandered off from his family and was captured by a slave trader who brought him to the area of what eventually became the Mukojima section of Edo. The boy died there from exhaustion and sickness. Later a wandering priest built a mound in memory of the boy. In time the Mokuboji temple compound was built there. The mound still exists today and every year a memorial service for the boy is held there on April 15.

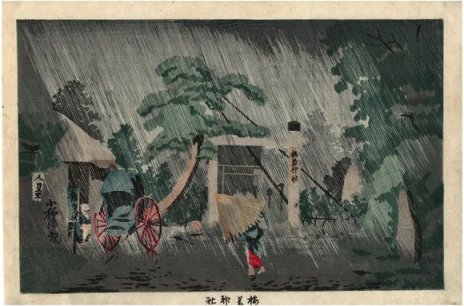

Above is a triptych by Yoshitoshi showing the boy Umewaka and the slave trader. This example is in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum. We found it at commons.wikimedia. The image to the left is by Kiyochika and comes from the Lyon Collection. It shows the shrine itself. |

|

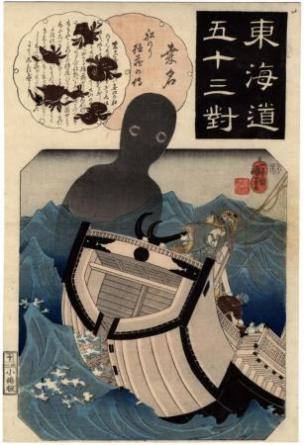

Umi-bozu |

海坊主

うみぼうず |

A sea monster, literally a 'sea monk'. "Some say they are vengeful souls of drowned sailors; others say they are strange mutations of deep-sea life taking monstrous supernatural form. Whatever the case, the Umi-bozu look nothing like any creature from this world, taking the form of jet-black, dome- or drop-like beings with glowing eyes. It has been suggested that they may actually be composed entirely of water, which would explain near-total absence of any other distinguishing features. Although many seem to lack mouths, they are often described as issuing an unsettling sighing or moaning sound. ¶ Umi-bozu come in a variety of sizes; the smallest, roughly four inches, are occasionally caught in fishing nets. Perhaps these are the juveniles of the species. Umi-bozu are large enough to menace fishing boats; at their largest and most fearsome they tower over the surface of the water."

Quoted from: Yokai Attack! The Japanese Monster Survival Guide by Hiroko Yoda and Matt Alt, pp. 50-52.

The image to the left is by Kuniyoshi and comes from the Lyon Collection. |

|

Umin |

羽民 うみん |

A creature with a human head, but with a feathered body.

"UMIN, flying men (same as Kafuri Umin). Several of these are also described as Goblins. Most are drawn from the chapters on the Ethnography of the foreign and barbarous countries in the Wakan san sai Dzuye and from other Chinese sources; Japanese artists, however, have not, as a rule, given much prominence to these creatures..." Quoted from: Legend in Japanese Art by Henri Joly, p. 69. |

|

Unbo (or unmo) |

雲母 うんぼ (うんも) |

Mica |

|

Utamaro and Sharaku both produced prints in the 1790s which are famous for their iridescent mica grounds. "The most common method for mica backgrounds employed two identical blocks. The artisan printed an undercolor (typically black sumi for grey, safflower rose for pink, a yellow; with no undercolor the mica alone printed a silver-white ground. Then coating another identically carved block with nikawa glue or rice-starch past he printed to moisten the same background area and then sprinkled on fine mica flakes, and, finally, shook off the excess. Another method required the mica, pre-mixed with color and thinned glue, to be printed in one step; another for the image to be blocked out with a stencil and the mica in sizing applied by brush." (Source and quote from: Color Woodblock Printmaking: The Traditional Method of Ukiyo-e, by Margaret M. Kanada, Shufunotomo Co., Ltd., 1989, p. 44)

"Personally I am not very fond of mica prints, and rather dubious of the prevalent custom in the market of valuing them highly simply because mica is used in printing. Still, I cannot deny the fact that the technique of using mica was very useful in improving the art of color prints." (Quote from: The Evolution of Ukiyoé: The Artistic, economic and Social Significance of Japanese Wood-block Prints, by Sei-ichirō Takahashi, published by H. Yamagata, 1955, p. 35)

"Utamaro not only invented kira-zuri (mica-print), but improved kizuri (yellow print) and nezumi-tsubushi (grey-print), tried his hand at kabe-zuri (sand print)...." In one print a beautiful woman is looking at her reflection in a mirror which is mica printed. (Ibid., p. 41)

See also our entry on kirazuri on our Kesa thru Kuruma index/glossary page.

U. A. Casal in his "Lore of the Japanese Fan", Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 16, no. 1/2, 1960, p. 86 noted that during the Tokugawa era one advancement in the making of the folding fan was the use of three or even up to five sheets of paper were glued together with rice paste "...and umbo, or ummo, mica, probably added for stiffness." |

||

|

|

||

|

Urashima Tarō |

浦島太郎

うらしまたろう |

Donald Keene in Seeds in the Heart: Japanese Literature from Earliest Times to the Late Sixteenth Century (pp. 569-70) says: "This tale was first recorded in the fudoki for the province of Tango in 713, and appeared in many different versions over the centuries, notably in the Kojidan (Tales About Old Matters), a collection compiled in the thirteenth century. In each version details differ, but the general outline remains the same."

The image to the left is from a photo taken by Toto-Tarou and posted at commons.wikimedia.org. |

|

Urauchi |

裏打 うらうち |

Backing or lining - a term used in judging the quality of a Japanese woodblock print. Many ukiyo-e prints have such a backing because they were originally mounted into albums. Sometimes they were backed simply to strengthen or support a sheet which has been distressed somewhat. |

|

Uri |

瓜

うり |

A melon - used by many different families as their crest or mon. John W. Dower notes that during the period of feudal warfare it was common practice to behead a captured enemy combatant adding that "...medieval chronicles record an instance of a warrior who used the silhouette of a melon as a crest because this shape resembled the pool of blood which formed after he had performed this custom on the body of a particularly renowned foe." (Quoted from: The Elements of Japanese Design p. 63)

Uri can also be translated as cucumber.

In the Man'yōshū (万葉集) there is a poem by Yamanōe Okura (山上憶良) called Thinking of Children. In the preface it notes that Buddha preached "No love exceeds a parent's love." The first lines of the poem reads:

When I eat a melon, I remember my children; When I eat chestnuts, Even more do I recall them.

Quoted from: The Blue-Eyed Tarokaja edited by Donald Keene, p. 181. |

|

"Melons (meron) are highly prized in Japan and those of excellent quality are also extremely expensive. Often given as presents, they are sold packaged in beautiful boxes, costing up to $200 U.S. for a single melon." This was written in 2009 in Sushi: Food for the Eye, the Body and the Soul by Ole G. Mourtesen, p. 264. On May 17, 2010 two Yūbari (夕張) melons were auctioned off in Saporo for approximately $16,300.00 according to Japan Today. But that is nothing compared to the pair of melons sold in 2008 for about a little more than $24,000.00. The Asahi Shimbun explained these prices by noting that only 54 of these treats were being offered at auction this year, down form 84 last year. Also, they noted that these melons had a higher sugar content. [Excuse us, but that's all crazy!] Below are two photos of these treasures posted by Captain76 at commons.wikimedia. We added the black background on the one on the left.

There is a kyōgen (comic skit) entitled Urinusubito (瓜盗人) or The Cucumber Thief.

There are numerous references to melons in poems, tales and legends. One of the best is about one of the greatest figures in early Zen development. Sometime after Shūhō Myōchō ( 宗峰妙超: 1282-1337) attained enlightenment he went to live with the beggars, i.e., outcasts, under a bridge in a dry river bed in Kyōto. A retired emperor heard about this and wanted this man to come and lecture at his court. Hearing that Myōchō was particularly fond of the makuwa-uri (真桑瓜), a particular kind of melon, the emperor disguised himself and went to the bridge. He took along a basket of these melons to hand out to the beggars. Believing that he would be able to recognize Myōchō from his reaction he looked closely at every man's face as he took the gift. One man's face lit up and his eyes sparkled. The former emperor saw this and said: " 'Take this without using your hands.' The immediate response was, 'Give it to me without using your hands.' " (Source and quote from: Eloquent Zen: Daitō and Early Japanese Zen by Kenneth Kraft, p. 42) In time the retired emperor gave Myōchō a new name: Daitō Kokushi, 'National Teacher of the Great Lamp'. ¶ Hakuin (白隠: 1686-1769) may have been the first to tell the melon story in ca. 1750 when he added a text to a portrait of Myōchō:

Wearing a straw mat among the beggars, through his greed for sweet melons he's been taken alive. "If you give me the fruit without using your hands I'll enter your presence without using my feet."

(Ibid., p.43)

The makuwa-uri (Cucumis melo var. makuwa) were grown under very loving conditions in the Kyōto region. In The Japanese Economy in the Tokugawa Era, 1600-1868 edited by Michael Smitka it gives a good description on p. 69 in an article by Toshio Furushima: "In the Kyoto region, for instance, melons knows as makuwa-uri were highly prized. By 1680 several villages had become well-known for producing handsome melon specimens, the best of which were produced near Tōji (temple) and sold with an affixed seal testifying to their origin. Farmers prepared and fertilized the plots for these melons during the preceding winter. When the plants first appeared in the spring, the farmers carefully observed each plant, keeping the most promising and thinning out the others. They even counted the leaves and cut the tops of branching vines to permit the main stem to grow larger and stronger. The top of the main vine was also pruned, and the next generation of vines was then allowed to bear fruit."

Above is a photo of two muskmelons - about $100.00 each in 2008. These were posted at commons.wikimedia by Bobok Ha'Eri.

Bashō wrote about the makuwa-uri. When sliced in half their parts mirror one another. He used this as an allusion to followers who don't break free of their masters and create their own styles. In 1690 Bashō wrote to "...Emoto Tōko (1659-1715), a merchant who asked to be his disciple. 'A melon cut in half' is a Japanese image for two people who are virtually identical." (Quoted from: Bashō's Haiku: Selected Poems of Matsuo Basho, p. 235)

In Joseph Needham's impressive series on Chinese science and culture it is written that the melon was one of the two most important fruit vegetables in ancient China. "Their young leaves could also be eaten as vegetables. Kua 瓜, melon, Cucumis melo L., sometimes known as thien kua 甜瓜 (musk melon) is eaten as a fruit. It has gained a certain degree of notoriety as a fruit which contributed to the untimely demise of the Lady of Han Tomb No. 1 at Ma-Wang-Tui. More than 138 melon seeds were recovered from her esophagus, stomach and intestines, indicating that she must have eaten the melon so fast that she swallowed the seeds without realising what she had done." (Quoted from: Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology, Part 5, Fermentations and Food Science by H. T. Huang, p. 33) The Chinese character 甜 means sweet. As kanji, where it also means sweet, it only appears with makuwa uri (muskmelon), sugar beet and beet sugar. ¶ This melon was mentioned in a 6th century compendium. (Ibid., p. 34)

Pickled melons are mentioned in the Shih Ching (Ch. 詩經) or Book of Odes from ancient China ca. 11th century B. C. to ca. 6th century B. C. Both the Chinese and the Japanese use the same character for pickling or steeping, 漬. (Ibid., pp. 18 & 74)

In the Yü Shi Phi or Imperial Food List compiled during the Southern Sung dynasty (1127-1279) melon soup is mentioned in the mix as worthy of noblemen. (Ibid., p. 128)

Robin Gill remarks on the Japanese and Western attitudes toward fresh produce are worth reading: "The difference between fruit in Japan and in the West cannot be described in these matter-of-fact contrasts about availability of taste. Most fruit in Japan, until the last two decades of the twentieth century, was more of a gift item then a grocery item per se. One bought fruit at the vegetable shop, or occasionally, at a fruit-shop, and carried it to wherever you visited, where they would serve part of it and you would get some, too. That is one reason why the huge ten-dollar apples and other incredibly expensive fruits sell so well in Japan. People are not buying them for themselves but as gifts. Fruit is also seen in abundance at funeral receptions." (Quoted from: Topsy-turvy 1585, p. 366)

"Makuwa uri first appeared in Japan in the Kyushu area near Korea; excavations from the Yayoi period have unearthed 2,100-year-old makuwa seeds. Minoru Kanda, of the seed company that bears his name, believes that the melon was named for a small village in Aichi prefecture, where farmers grew the best uri fruits." (Quoted from: Melons for the Passionate Grower by Amy Goldman, p. 108)

Some of the

families that used the uri as their crest or mon: the Oda (織田);

the Asakura (朝倉); the Sakurai (桜井); the Takagi (高木);

the Tanaka (田中); Yagi (八木);

Ueno (上野); Kamada (鎌田); Ishino (石野); Magabuchi (曲淵); Kawashima (川島); Wada (和田); Yamaoka (山岡); Akira

(明?); Ban (伴); Fukatsu (深津); Kuroda (黒田) at Karuri; Maruyama (まるやま); Asano (浅野) at Hiroshima - their mon

includes crossed feathers or

takanoha in the center; Kurusu (栗栖); Takikawa

(瀧川); Tominaga (冨永); Yoshida (吉田); Hotta (堀田)

at Sakura, Satto and Miyagawa; Kano (?尾); Sagara (相良); Nishimura

(西村); Fushiya (伏屋); Murakami (村上); Takudaiji (徳大寺); Miya (高); Akimoto (秋元); Arima (有馬); Shibue (渋江); Tsuda (津田); Ōbayashi (大林); Nakai (中井); Saita

(齊田); Ōmura (大村); Ōta (大田); Hitome (人見);

Nakagawa (中川); Onodera (小野寺); Shinoyama (篠山); Itō (伊藤); Kawata (河田); Sasatake (佐佐竹); Watada (和多田); Sano (佐野); Iida (飯田) and Uragami (浦上). Several clans use the uri motif

with the

mitsu tomoe (三つ巴) or three

comma shapes in the center. These include the Ikuta (生田), Kuno (久野), Murayama (村山), Sawai (澤井) and Wada (和田).

(Source: Mon: The Japanese Family Crest by Kei Kaneda Chappelear and W. M.

Hawley, pp. 18-19) |

||

|

|

||

|

Uroko |

鱗

うろこ

|

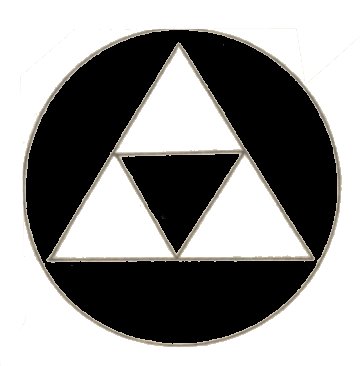

A fish scale motif used on fabrics and other objects. According to John W. Dower this triangular fabric motif existed long before it was described as a fish scale pattern "...and its most illustrious association was with the powerful Hojo family, who ruled Japan for almost a century and a half at the beginning of the feudal period.

Quoted from: The Elements of Japanese Design p. 146.

In The Actor's Image: Print Makers of the Katsukawa School Timothy Clark notes that Musume Dōjō-ji (The Maiden at Dōjō Temple) "...has shrugged her over-kimono (uchikake) off her shoulders to reveal the triangular snake-scale pattern (uroko-gata) of the kimono, and her long hair hangs down in a wild ponytail that will whip through the air like a snake as she dances." In here bitterness over being shunned the maiden transforms into a snake. This makes more sense here than the rather limited reference to fish scaling.

Clark is writing about a Shunshō print (Cat. #62, p. 183). |

|

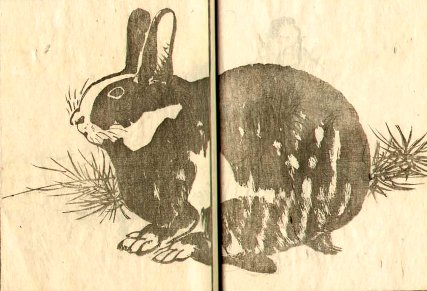

Usagi |

兎

うさぎ

|

Rabbit, hare or cony 1

|

|

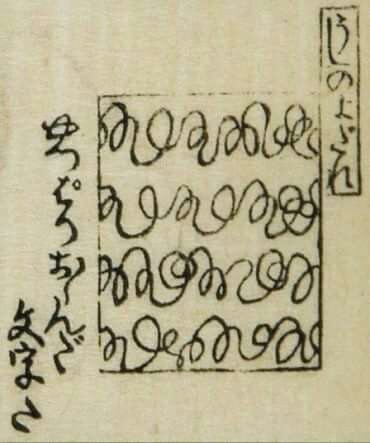

Ushi no yodare |

牛の涎

うしのよだれ |

Cow drool - This was a derisive term Santō Kyōden (山東 京伝 : 1761-1816) used for the way Westerners wrote. Kyōden had created a pattern book of parodies of textile patterns and the image to the left was one of those entries. Keiko Suzuki wrote of this piece: "The pattern is quasi-letter doodles that, at a glance, look like Roman letters in cursive script. The attached text states, “Dutch letters as I thought.” Kyōden explains this in the revised book Komon gawa.., playfully saying that “the Dutch make sense out of letters written in cow’s drool…” An important point is that Kyōden makes fun of not only Roman letters but also the letters of India and China. He mentions: “In Tenjiku [India], letters were inspired by wood shavings…. It has been said that Sōketsu [Cang Xie] of Tang created letters from the tracks of the bird...” |

|

Ushi oni |

牛鬼

うしおに

|

A monster with a bull's head with a spider's body: "The Ushi-oni has quite an ancient history, getting a brief mention in Sei Shōnagon's 11th century Pillow Book (“far more terrifying in appearance than its name suggests”) and the later 14th century historical epic Taiheiki In regional legends, it is said to be married to Nure-Onna... In these tales, Nure-Onna appears on the coastline, hands an infant to a passer-by, and then walks into the waves; the baby's weight increases crushingly, pinning the passer-by to the spot, whereupon the Ushi-oni emerges from the waters and attacks them." Quoted from: Japandemonium Illustrated: The Yokai Encyclopedias of Toriyama Sekien by Toriyama Sekien, p. 70.

We found this image at the Japanese version of Wikipedia.

|

|

Ushirometai |

後ろめたい うしろめたい |

Having a guilty conscience: According to Kazuhiko Komatsu "Although it has largely been forgotten since disposability has become the order of the day, the Japanese once had a different attitude toward their household goods. They felt guilty about throwing things away, especially utensils made by human hands. The word used for these guilt feelings, ushirometasa, literally means 'feeling someone's gaze behind one's back.' One has done something improper: anyone secretly watching would surely disapprove. The gave implied by ushirometasa includes that of fellow humans, but traditionally it carried stronger connotations of the gaze of a divine spirit. When a utensil is discarded, the agent of the gaze is the spirit of the utensil itself." (From the Japan Foundation Newsletter, vol. XXVII, no. 1, June 1999)

|

|

Ushiwakamaru |

牛若丸 うしわかまる |

"Ushiwakamaru is the name given to the young Minamoto no Yoshitsune (1159-1189), the most popular tragic figure in pre-modern Japanese culture. He was the youngest of three sons born to Tokiwa Gozen, (b. 1135), mistress of Minamoto no Yoshitomo (1123-60). After Yoshitomo was killed in the Heiji Insurrection (1159), the victor, Taira no Kiyomori (1118-1181), was persuaded to spare the lives of Tokiwa and her children. When Yoshitsune's half-brother, Minamoto no Yoritomo (1147-80), raised a new revolt against the Taira, Yoshitsune joined his cause."

Toyokuni III diptych of Ushiwakamaru fighting with Benkei on the Gojō Bridge. This comes from the Lyon Collection. |

|

Utagawa Hirosada |

歌川広貞 うたがわひろさだ |

Artist fl. 1819-65 1 |

|

Utagawa Hiroshige II |

二代広重 うたがわひろしげ |

|

|

Utagawa Kunisada |

歌川国貞

うたがわくにさだ |

Artist 1786-1865.

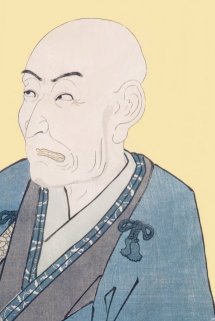

The image to the left is a detail from a memorial print by Kunimaro. Kunisada by this time is identified by most scholars as Toyokuni III.

The odd thing about memorial portraits is that they always portray artists at the end of their careers and thus, as a rule, old men. Considering the East Asian respect for age this is not surprising. However, this seems to be just the opposite of a common practice in the West. If one were to read the obituary columns on a regular basis one would notice a pattern whereby the deaths of people in their eighties and nineties are often accompanied by photographs taken when the deceased was in their prime - often in their twenties or thirties. Somehow the Japanese memorial prints have a little more truth to them - at least from my point of view.

Sebastian Izzard, who we believe is the world's greatest expert on Kunisada, wrote in Impressions, Official Publication of the Ukiyo-e Society of America, Inc. No. 3, Spring, 1979: "Kunisada, who began to design bijin-ga seriously around 1813/14, devoted at least 30% of his output to this theme. He continued to do so until his death in 1864 and thus has given us a unique record of the ideal feminine physique and contemporary fashion of the early half of the nineteenth-century in Japan."

Izzard quotes Ficke, who referred to Kunisada as a 'decadent'. Ficke talked about "...all that meaningless complexity of design, coarseness of colour amd carelessness of printing which we associate with the ruin of the art." [Of course, no real scholar or collector feels that way today.] |

|

Izzard writes: "Kunisada was born in Honjo Itsusume in the province of Boshu in 1786. His father was a ferryboat owner who kept the 'fifth ferry' station on the Tatekawa, a small tributary which entered the Sumida River just below Ryogoku Bridge in Edo." Kunisada's father "... was a ferryboat owner who kept the 'fifth ferry' station on the Tatekawa, a small tributary which entered the Sumida River just below Ryogoku Bridge in Edo." This is important because "In 1812 Kunisada's friend, the poet Shokusanjin, gave him a new go Gototei, meaning 'Pavilion of the Fifth Ferry,' when Kunisada inherited his father's business. From this date until 1844 he employed this go, though after 1830 it is largely restricted to theatrical prints. In 1827 Kunisada entered the school of Hanabusa Ikkei, a painter who worked in the tradition of Hanabusa Itcho. From Itcho's name Kunisada derived his go of Kochoro, of which the first clearly datable example is 1830. He used this name concurrently with Gototei until 1844, when he took the name Toyokuni II..." |

||

|

|

||

|

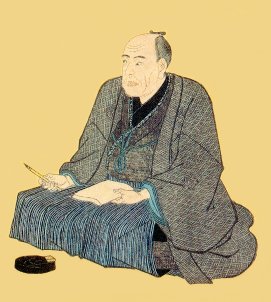

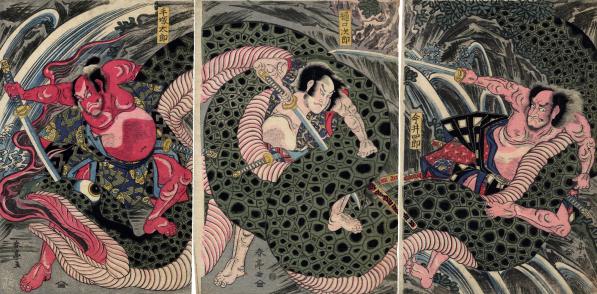

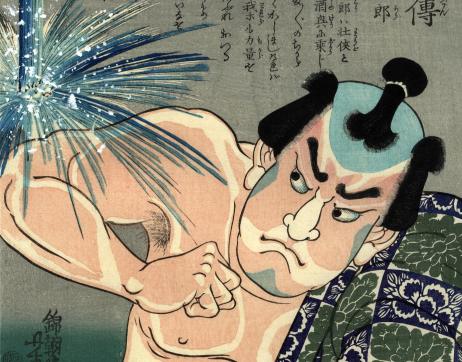

Utagawa Kuniyoshi |

歌川国芳

うたがわくによし |

|

|

Utagawa Toyokuni I |

歌川豊国 うたがわとよくに |

Artist 1769-1825 1 |

|

Utagawa Yoshikazu |

歌川芳員 うたがわよしかず |

Artist fl. 1850 - 70 1 |

|

|

蠎 (or 蟒蛇) うわばみ |

A python or a very large snake

by Shuntei from ca. 1806 - the Lyon Collection |

|

Uwanari |

嫐 うわなり |

The name of a kabuki play. Elsewhere it is a secondary wife or wives. Literally the kanji character translates as 'flirt with', 'play with' or 'frolic'.

The image to the left is by Kunichika and is from the Lyon Collection. Click on it to learn more. |

|

Uwanari uchi |

後妻打ち うわなりうち |

Secondary wife beating: "This scene of jealous rage and violence on stage refers to the Muromachi practice called uwanari uchi, or 'secondary wife beating,' which describes the violence committed by a man's original legal wife (konami) who had lost her husband's favor and support against a supplanting secondary wife or wives (uwanari). Uwanari uchi was also performed sporadically during the Heian period (794-1185), but it was not until Muromachi that it became a full-blown social practice. A dramatization of uwanari nchi also occurs in Zeami's Kanawa (Iron crown), in which a jealous wife, who has been cast aside by her philandering husband in favor of another woman, seeks to avenge her humiliation by transforming herself into a demon and attacking a pair of dolls, which serve as substitutes for the husband and his new lover. In the end, her supernatural fury is subdued through the efforts of a sage named Abe no Seimei." Quoted from: Theatricalities of Power: The Cultural Politics of Noh by Steven T. Brown, pp. 62-63.

The image above is a triptych by Hiroshige seen at the Lyon Collection. Click on it to learn more. |

|

Valentino, Rudolph |

ルドルフ バレンティノ |

American actor, 1920s 1 |

|

Wachigai |

輪違

わちがい

|

Dower gives no clear explanation for this motif which was used in numerous variations as a mon or family crest. However, he does state: "This motif is alleged to have been abstracted from a larger overall design of a manner similar to that in which the 'seven treasures' motif... originated."

Quoted from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 133.

(See our index/glossary entry for shippō.)

|

|

Wakisaka Yasuharu (脇坂安治: 1555-1626) was a general who served under the command of Kobayakawa Hedeaki at the battle of Sekigahara in 1600 and went with him when he went over to the side of Ieyasu. Below is a legend marker with two of Yasuharu's ensigns or hatajurushi (旗標) at the site of his location at that battle. His crest was made up of two linked rings.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Waka |

和歌 わか |

"...waka (verse form) of thirty-one syllables in five lines." Quoted from: World's Within Walls by Donald Keene, p. 11.

"The characteristic verse form of the pre-modern period was, of course, haikai, but immense quantities of waka were also composed by men at the court and in every part of the country. Most of this poetry is undistinguished, despite the care, scholarship, and intelligence everywhere apparent. In reading the works of even the most accomplished waka poets we find ourselves looking not for any particular qualities of either the men or their age but for telltale influences from the past, whether revealed in archaisms and other stylistic features or in the attempts to evoke ideals associated with distant epochs." (Ibid., p. 300)

"Some merchants, however, began a conscious search for access to aristocratic culture. Ambitious citizens of this kind began an active appropriation of Japan's classical past. Until the advent of commercial printing, access to classical culture had been restricted for over 500 years to the Kyoto upper classes (courtier or samurai). For a commoner to attempt to be a waka poet and thereby be accepted as an equal by the aristocracy was a political act, because waka was their property. Bookshops and lending libraries gave the masses access to the cultural treasurers of the past as never before, but we know from courtier diaries in the seventeenth century that aristocrats remained disdainful towards even sophisticated commoners." Quoted from the preface to 18th Century Japan: Culture and Society. |

|

|

和歌三神 わかさんじん |

The three gods of poetry: Tamatsushima (玉津馬), Sumiyoshi (住吉) and Kakinomoto no Hitomaro (柿本人麻呂). The image below, a surimono, is by Hokkei and is in the collection of the National Museum of Asian Art.

|

|

|

若衆

わかしゅ |

Joshua Mostow wrote: "Unlike many words in the Japanese language, the noun "wakashu' has no Chinese precedent, which is to say that the word does not originally come from China, nor was it used there. The two characters that compose it mean literally "young" and "the multitudes" or "companions." Thus there is nothing gendered about the term etymologically, but as Gregory Pflugfelder has noted, the referent was understood to be male, just as with its closest English equivalent, "youths." "

The image to the left is from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It is a painting by Miyagawa Isshō (1689-1780). |

|

Wakige |

腋毛

わきげ |

Armpit hair - Normally we wouldn't discuss such things, but occasionally and only rarely does armpit hair appear in Japanese ukiyo-e prints. Therefore we decided it was worth mentioning. Now we have mentioned it and can move on.

The image to the left is a detail from an Eisen print showing a woman bathing. It dates from 1842. The detail above is from a Yoshitora print from 1866. Both examples are from the Lyon Collection. |

|

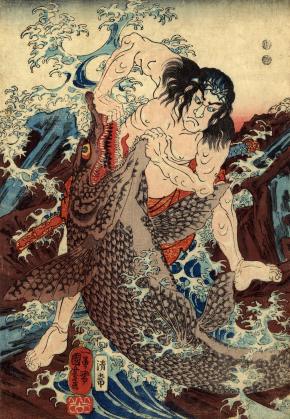

Wani |

鰐 わに |

Wani means both crocodile or alligator - "Taoists in China credited the crocodile with an ability to summon spring rains and viewed it as a type of dragon. In line with this belief, ancient Chinese rain-making ceremonies sometimes employed drums covered in crocodile skin. From ancient times, the Japanese used the word wani to designate a sea monster. When the Chinese system of writing was adopted, wani was written with the ideograph [鰐] for crocodile, and it is thus likely that most references to crocodiles in early documents and myths refer not to the crocodile specifically but rather to a generic sea monster. ¶ In Japan, crocodiles figure in a number of legends of Chinese pedigree. Further, a type of hollow wooden drum in the shape of a fish head, associated with Shinto observances, is known as a wani-guchi (crocodile mouth)." Quoted from: Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design by Merrily Baird, p. 129.

Both images shown here come from Kuniyoshi triptychs in the Lyon Collection. Click on them to see the full image.

|

|

Wanko soba |

椀子蕎麦

わんこそば |

Small bowls of soba with a dipping broth 1

|

|

Warabi |

蕨

わらび

|

Bracken: A crest or mon used by various families. "The new shoot of bracken that emerges in early spring is likened by teh Japanese to a fist (by the name warabide, bracken-hand). This became the basis of a fairly popular pattern used on household items, and a small number of families eventually adopted the motif as a family crest." Quote from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, published by Weatherhill, 1991, p. 50.

Note that there is a large number of variations of this motif some of which are hardly recognizable as being related.

In the Kodansha Encyclopedia there is an entry on the 'fern frond design' or warabidemon (蕨手紋): "A curved-line motif ending in a tight spiral resembling a newly unfolding fern frond, used singly or in pairs back to back on artifacts of the Yayoi (ca 300 BC - ca AD 300) and Kofun (ca 300-710) periods, especially on Yayoi pottery, bronze bells... bronze weapons, bronze mirrors, haniwa (funerary sculptures), and in the painted decorations of ornamented tombs." Quote from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan entry by Kitamura Bunji (vol. 2, p. 252).

In an article in Japanese, Notes on the Fulfilment of Vows and Other Matters, by Hosokawa Tashitarō it says: "When the coffin is carried out of the house, brake fern (warabi) is burnt at the door, and the tea-cup which the dead was accustomed to use is smashed."

Bracken or fiddlehead ferns are a modern culinary delight. For that reason and to strengthen the visual tie between the Japanese crest and the physical plant we have added two images here both found at wikimedia.org. The one above was originally posted at Flickr by John Herschell and the one below was posted at en.wikipedia by Pseudopanax.

|

|

Waraji |

草鞋

わらじ |

Straw sandals: "A traditional rough straw sandal, with a thong passing between the big and second toes; tied onto the foot with straw straps, which pass through a series of loops on the sides of the sole. Not to be confused with the finer straw sandal, zōri, which is held onto the foot by the thong alone. Materials used include plain rice straw, flax (asa) fibers, wisteria or grape fibers, and straw interwoven with cloth strips. Waraji were used throughout Japan and worn when taking long journeys on foot. Their manufacture was one of the evening's tasks in a farm household; in many regions making waraji was the first task of the New Year." Quoted from the entry by Miyamoto Mizuo in the Kodansaha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 8., p. 223

The image to the left is from a manga by Hokusai. Above is a photo of waraji on a tatami. It was posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Andy King50. The image of the person wearing waraji shown in the section below was posted at the same locale by Corpse Reviver. |

|

In Our Own Devices: How Technology Remakes Humanity by Edward Kenner it says that waraji were originally made of rice straw about 2,000 years ago - pre-dating the geta, another type of footwear. The zori, based on the design of the geta was introduced in the 9th century. Because rice was both a staple and a religious commodity sloughed off rice straw held religious significance, too. Shimenawa, twisted rice straw ropes, demarked sacred locations. Roofs, mats, raincoats and hats were made from it. Even "An immense straw waraji, supported by more than twenty bearers, was recently dedicated [ca. 2004] to Tokyo's Sensoji temple, as the embodiment of the protection of the nation."

Lafcadio Hearn described long journeys taken by the students of a fencing school: "They walk in waraji, the true straw sandal, closely tied to the naked foot, which it leaves perfectly supple and free, without blistering or producing corns."

Hearn also writes about a priest who is determined to get rid of bimbōgami (貧乏神), the god of poverty. The priest "...had a strange dream, in which he saw a very emaciated boy, naked and dirty, weaving sandals of straw (waraji), such as pilgrims and runners wear; and he made so many that the priest wondered, and asked him, 'For what purpose are you making so many sandals?' And the boy answered, 'I am going to travel with you. I am Bimbogami.' "

Nozawa Bonchō (野沢凡兆: d. 1714) wrote: "Without a sound/ hands make straw into sandals/ in the moonlight."

At one of the festivals in Japan an over-sized waraji is floated out to sea to placate or repel the monsters which accompany the typhoon season.

There is a novel by Jippensha Ikku (1765-1831) called Kane no waraji (金草鞋) or 'Sandals of Steel' from 1813. Shirane translated the title as 'Straw Sandals of Gold'.

"Footgear was also standardized. The poor wore sandals of straw called waraji which could be woven very quickly and cheaply. Waraji were also the basic footgear for travelers." Quoted from: The Cambridge History of Japan: Early Modern Japan by John Whitney Hall, p. 691.

Basil Hall Chamberlain wrote in his Things Japanese (p. 121): "Of straw sandals there are two kinds, the movable zōri used for light work, and the waraji which are bound tightly round the feet with straw string and used for hard walking only."

Horses were sometimes shod in waraji. Below is a detail from a Hiroshige print. It is also used to illustrate our Shigenobu entry.

On page 8 of a 1920 publication of the Victoria and Albert Museum the authors stated that waraji were so flimsy that they lasted only 24 hours on average. Workers normally carried extra pairs with them. On the positive side this footwear was extremely inexpensive. |

||

|

|

||

|

Washi |

和紙 わし |

Japanese paper 1 |

|

Whistler, James McNeill |

ホイッスラー |

Great 19th c. painter and print maker who occasionally printed on Japanese papers. Many of his paintings show the influence of Japanese art. 1 |

|

Willow Pattern |

|

A popular 19th c. blue & white porcelain motif 1 |

|

Worcester |

ウースター |

An English porcelain factory which reproduced Asian motifs 1 |

|

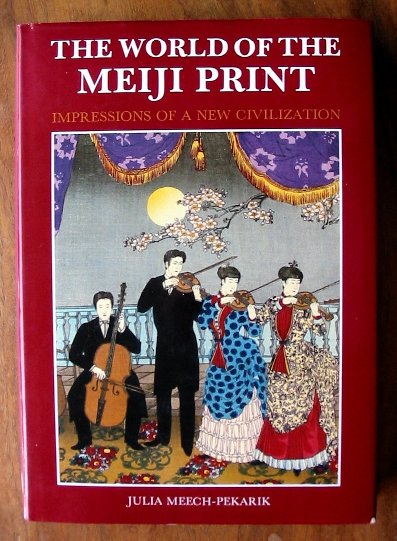

The World of the Meiji Print: Impressions of a New Civilization |

|

Like so many other specialized books this volume by Julia Meech-Pekarik and published by Weatherhill in 1986 is of use to anyone interested in Japanese culture in general. 1, 2 |

|

Ya |

矢 や |

Arrow: "The arrow too in ritual situations on the Asian continent is less a weapon than an instrument which magically joins two worlds. Shot into the air it will apprise a deity that a rite is about to take place.... At the beginning of the fire ritual known as saitō-goma, still practised by the mountain ascetics called yamabushi, an arrow shot in each of the five directions is the means of informing the Five Bright Kings who preside over the order that the rite is about to begin. The miko's arrows may have been put to similar use, to summon the kami and warn him that his descent is required. (Source and quote from: The Catalpa Bow: A Study of Shamanistic Practices in Japan by Carmen Blacker, p. 107)

|

|

Yabusame |

流鏑馬

やぶさめ |

Archery from horseback - 流 means 'method of' or 'manner of', 鏑 means 'arrowhead' and 馬 is 'horse'.

Royall Tyler in his translation of The Tale of Genji - in a footnote on p. 170 - notes that yabusame was practiced in the Heian times. "...yabusame riding events that took place on the third and fifth days of the fifth month."

"Le Yabusame n'est ni un sport ni un art martial, mais un rituel religieux dont l'objectif est de réjouir les dieux par son habileté et son pouvoir..." Quote from a Michelin guide to Japan

From Japanese Warrior Monks AD 949-1603 by Stephen Turnbull, p. 31: "The arrows were of bamboo. The nock was cut just above a node for strength, and three feathers were fitted. Bowstrings were of plant fibre, usually hemp or ramie, coated with wax to give a hard smooth surface, and in some cases the long bow needed more than one person to string it. The archer held the bow above his head to clear the horse, and then moved his hands apart as the bow was brought down to end with the left arm straight and the right hand near the right ear. A high level of accuracy resulted from hours of practice on ranges where the arrows were discharged at small wooden targets while the horse was galloping along. This became the traditional art of yabusame, still performed at festivals."

"Near the end of the twelfth century, Yoritomo initiated stricter training standards for his warriors. As part of the training he instructed Ogasawara Nagakiyo, the founder of Ogasawara Ryu, to teach mounted archery. Shooting from horseback was certainly not new but this was the first time it was taught in a more or less standardized way. In the years that followed, yabusame, or mounted archery, would reach its full potential, thus adding a new dimension to the study of kyudo." Quoted from: Kyudo: The Essence and Practice of Japanese Archery, p. 16.

The trimmed image to the left was posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Jim Mills. |

|

"According to Azuma kagami (The Mirror of the East, the shogunate's chronicle), in the third year of Bunchi (1187) an annual yabusame ritual (a game in which mounted warriors shoot arrows on the run at fixed targets) was conducted at the shogunate's official shrine, Tsurugaoka Hachiman. Many samurai were assigned to different tasks during the ritual, and Kumagai Naozane was asked to stand and hold the targets. He was very angry about this assignment: 'All the vassals of the shogunate are equal fellows. Those who were assigned to be shooters were mounted, but the men taking care of the targets were on foot. It looked as if there was a hierarchy. I just could not accept such an order.' ¶ In the community of the samurai, riding on horseback was an important indicator of status. Only mounted warriors were considered real samurai. The shogun Yoritomo tried to placate Naozane by saying that responsibility for the targets was not inferior to shooting, but Naozane refused the task. Because he rejected the order of the shogun, a part of Naozane's property was confiscated. For this stubborn samurai, the notion of equality among the vassals of the shogun was a part of his sense of honor that he could not compromise. The episode indicates vividly how the indomitable spirit of the samurai's honor was connected to his sense of independence and dignity. The relative socioeconomic independence claimed by followers in the medieval system of vassalage created the basic sentiment of samurai culture, which embraced the individualistic pursuit of a reputation for strength and power." Quoted from: The Taming of the Samurai: Honorific Individualism and the Making of Modern Japan by Eiko Ikegami, p. 83.

According to The Way of the Warrior: Martial Arts and Fighting Styles from Around the World (p. 224) when the archer releases an arrow he yells "Yo-in-yo" which means "darkness and light". |

||

|

|

||

|

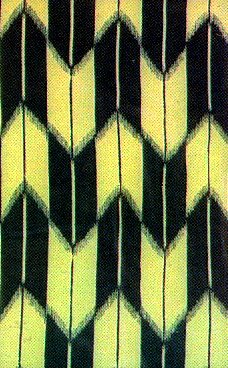

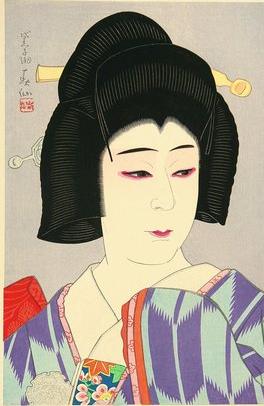

Yagasuri |

矢絣

やがすり |

Arrow motif for fabrics - Ruth Shaver in her book Kabuki Costume wrote on page 163: "The koshimoto [hand-maiden] repeatedly wear the yagasuri or arrow-patterned kimono, a rather quiet garment that achieves great dignity when properly worn. The purple-and-white yagasuri kimono is traditional for the role of Okaru in the renowned "Michiyuki" scene of Chūshingura." Below is a Natori Shunsen representation from 1951 of Onoe Baikō VII as Okaru.

In Traditional Japanese Theater: An Anthology of Plays edited by Karen Brazell it defines yagasuri as "Arrow-patterned kimono worn in kabuki by the daughters of samurai serving in court or by the daughters of wealthy merchants." |

|

Yagō |

屋号 やごう |

A stage family name; a [hereditary] stage title; the name of a house; a store or shop name - "During the early days of Kabuki, the actors acquired family names, many of which survive to this day, even though it was illegal for anyone but the samurai class to have more than a "given" name. Many acting families, such as the Ichikawa, the Onoe, and the Nakamura sprang from samurai stock and so had family names already, although they had forfeited the rights to use them. The actors' "given" and family names were always displayed outside the theatres, but if the police chose to apply the law strictly, these family anmes could be removed and the actors' yago substituted. The yago is not a nickname but a title, often founded on some local association; Naritaya, the yago of the senior branch of the Ichikawa, comes from a particular association of that family with the great Fudo Shrine at Narita; Otowaya, the yago of the Onoe, is derived from the family name of their ronin acestor [sic]; Yamatoya, the yago of the Bando, from the part of Japan from which the family originated. The "ya" in these titles is the same as the "ya" in the names used by merchants, who substituted their "trade-names" (yaoya - greengrocer, kamiya - paper seller, etc.) for family names much as medieval tradesmen in Europe called themselves "Smith" or "Gardener." Any member of the acting family can be called by the yago of his family, but traditionally it is always particularly associated with the senior members. To shout an actor's yago is the most popular way of applauding." Quoted from: The Kabuki Handbook by Aubrey and Giovanna Halford, p. 396. |

|

Yagura |

櫓 やぐら |

Tower or turret used to traditionally mark the site of a licensed kabuki theater. It is also referred to as a drum tower. |

|

Yajirobei |

彌次郎兵衛

やじろべえ

|

This is the name of one of the two comic figures of The Shank's Mare by Jippensha Ikku. It is also the name of a balancing toy as shown here. 1

"Yajirobei balancing dolls were made to look as if he was carrying packages (by balancing them across his shoulders). His name was not only well-known as the balancing doll, but also as a collective term for the balancing games played in Edo times." Quoted from: Pattern Sourcebook: Japanese Style 2 by Shigeki Nakamura, p. 18.

There is a book illustrated by Itchō from 1770 in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art which shows a peddler of Yajirobei toys drawing the interest of 3 children. |

|

Yakara no tama |

やか

|

The flaming jewel motif.

See also our entry for hōju. |

|

Yakata-bune |

やか

た

|

A roofed boat used for pleasure outings.

"Suzumi-bune [涼み舟] or 'cooling boats' were the most luxurious method Edo residents utilized to cool themselves in summer. Sitting on richly decorated boats and surrounded by beautiful women and many servants, they enjoyed cool breezes as their boats slowly glided down the Sumida River, while they drank sake and ate delicious food."

"The 'cooling boats' were specially constructed and were generally called yakata-bune or roofed boats. Some them were quite big, reaching a length of more than 50 to 60 feet."

Said to have begun during a particularly hot summer during the Keicho era (1596-1614). In time they became ostentatious signs of prestige and wealth and full-blown entertainment centers.

Source and quotes from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, pp. 500-1.

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Hiroshige. |

|

Yakko |

奴

やっこ |

"Yakko is the costume worn by the lowest order of servants or footmen, who are also known as yakko or chūgen. These men are attached to the households of military men and for that reason appear in jidai-mono. Servants of the same status working for the daimyō were called ashigaru. ¶ When the yakko had no special duty, he cleaned the garden, chopped wood, or accompanied his lord as a footman, and toward evening, when his lord went visiting, the yakko was permitted to wear one sword. Though he was considered unqualified to go into battle, he took charge of the horses and cleaned his master's swords within the battle encampment. ¶ Chōbei of Banzuin (the Banzuin Chōbei of Kabuki fame), purported to be the most admired otokodate, started his adult life as a chūgen. Though these people came from the underprivileged class of the community during Edo,they were treated somewhat as heroes by the public, since some of their members became Kabuki actors. Danjūrō I was a chūgen, then an otokodate before becoming an actor. The rise of chūgen to the status of actors gave the commoners a feeling of intimacy, one of sharing, with the men who had broken from their ranks. ¶ The Kabuki yakko or chūgen is a handsome, a charming, or a foppish servant referred to as either iro-yakko (iro, color or sensual passion) or shusu (satin) yakko. He is played by an outstanding mature actor or a promising young one. In the past, the yakko took a rather prominent part in historical plays, but his parts are not so major today." Quoted from: Kabuki Costume... by Ruth Shaver, pp. 137-138.

The image to the left is by Ashiyuki and comes from the Lyon Collection. |

|

LINKS TO OUR OTHER INDEX/GLOSSARY PAGES Click on any of the pages listed below!

|

||

|

Hotoke thru Igaya |

||

7b_Pseudopanax.jpg)

HOME

HOME