|

|

|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

A thru Aobanagami |

|

|

The orange flowers from the grounds of the Linda Hall Library in Kansas City are being used as markers to new additions and/or corrections for June 1 thru December 31, 2021. The molecular model on Lonsdaleite was used from January 1 to May 31, 2021. |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Abi jigoku, Abumi, Abuna-e, Abura-akago, Abura-sumashi, Ageboshi, Ageha no cho, Ai, Aidono, Aigami, Aiguma, Aizome, Aizuri-e, Ajirogasa, Ajisai, Aka-e, Akane, Aka-tonbo,

Aki no nanakusa, Aku,

Akushō, Amagasa, Amagatsu, Amagoi, Amanohashidate, Amano Iwato Shrine, Amanojaku, Ame, Ame ni nuretsubame, Ameya, Ami, Andon, Ankō, Aobana, Aobanagami

阿鼻地獄, 鐙, 危絵, 油赤子, 油すまし, 揚帽子,

揚羽蝶, 藍, 相殿, 藍紙,

藍染, 藍摺絵, 網代笠, 紫陽花,

赤絵,

紅蜻蜓,

茜, 秋の七草, 悪,

悪所, 天児, 雨乞い, 天の橋立, 天岩戸神社, 天邪鬼, 雨, 雨に濡れ燕, アメリカ原住民, 飴屋, 網, 行灯, 鮟鱇, 青花, 青花紙 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Abi jigoku |

阿鼻地獄

あびじごく |

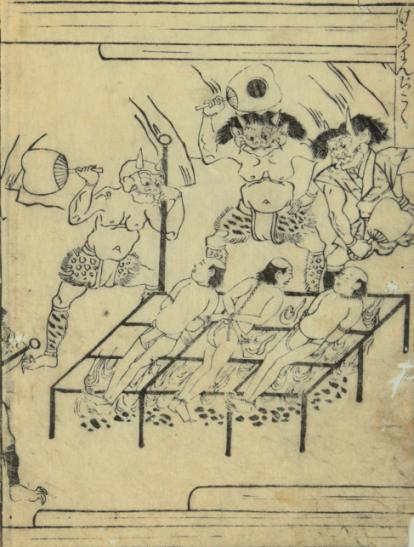

The Avici hell, the 8th and most painful - the Unremitting Hell: "The lowest and the most cruel of all hells is called the Unremitting Hell (abi jigoku 阿鼻地獄, the abode of those guilty of the five crimes, of those who denied the principle of cause and effect, who cursed the Mahayana teachings, broke the precepts, improperly took alms from believers, and burnt Buddhist images and lodgings belonging to monks. This hell is dominated by a castle surrounded by seven walls, protected all around by a forest of swords and by four huge dogs made of copper, put in the four corners of the castle. The dogs’ eyes are as bright as lightening, their teeth as sharp as swords, and their tongues are similar to iron thorns, while their pores emit flames producing a stinking smoke. Each of the fiends guarding the castle have sixty-four eyes which cast iron bullets against the prisoners kept inside. On the four doors of the castle lay eighty pots full of melted copper which flows all over the castle and its inhabitants. Pythons and other poisonous snakes cover the walls, and insects emit flames from their countless mouths, making the Unremitting Hell the hottest of all, where sinners, pains do not know a moment of rest. People here are made to climb extremely hot iron mountains and to swallow hot bullets which burn the victims’ bowels. Those who have stolen food from monks are moved by such a violent hunger and thirst that they end up eating each other..." Quoted from: "The Development of Mappo Thought in Japan" by Michele Marra in the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 1988, p. 44.

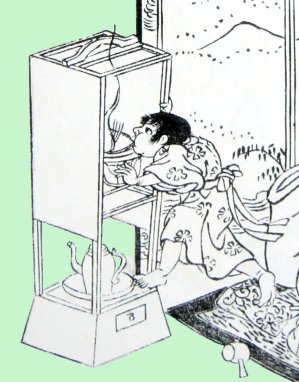

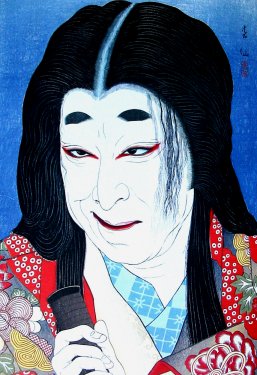

The image to the left is based on a text by Genshin (源信: 942-1017), but is not specifically meant to represent this level of Hell. However, my guess is that it can't get much worse. |

|

A description of the Avici hell appears in Carmen Blacker's The Katalpa Bow: A Study of Shamanistic Practices in Japan, pp. 166-167: "A similar case can be found in the fourteenth-century work Taiheiki. An itinerant priest found himself summoned by a yamabushi to a certain temple, and told to recite the eighth book of the Lotus Sutra, and to continue reciting the holy text, however terrible the sights that might appear before him. Past midnight there was manifested before his eyes a vision of the Avici hell, in which he saw his wicked kinsman Yūki Kōzuke Nyūdō subjected to unspeakable torments. Time and again he was killed in an agonising manner, and brought to life again by means of winnowing basket. Go at once to the man's wife and children in the north, the yamabushi told the horrified priest, and instruct them to recite the Lotus Sutra every day, Only thus can he be saved. Dawn then broke, and the priest found himself alone on a dewy moor. The prospect of hell and the yamabushi had both vanished. At once he made his way to the man's family and related his vision to them. At first they were incredulous, not yet realising that the Nyūdō was dead. But a day or two afterwards a messenger arrived with the news of the Nyūdō's terrible end. They therefore lost no time in reciting the prescribed sutra every day for the space of forty-nine days. The salvation of this wicked man was thus accomplished ultimately by the power of the Bodhisattva Jizō, of whom the yamabushi was a transformation, but effectively by the itinerant priest who carried the message of the vision." |

||

|

|

||

|

Abumi |

鐙

あぶみ

|

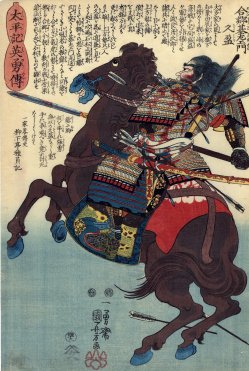

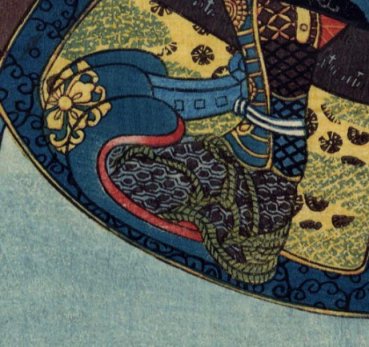

Stirrup: The oldest stirrups found in Japan were in a tomb from the Middle Kofun period. The fellow buried there died in 415. These items were known as wo-abumi (輪鐙) or ring-stirrups. They predated the tsubo-abumi (壷鐙) or pot-stirrups which were closed around the feet.

William George Aston in A Grammar of the Japanese Written Language published in 1904 says the word abumi comes from 'ashi' or foot and 'fumi' or tread.

Below is an example of a warrior print from the Lyon Collection. Next to it is a detail from that print. Click on it to see the full image and information.

To the left at the bottom is a 5th to 6th century Kofun period haniwa horse clearly showing a stirrup. It was posted at commons.wikimedia by Sailko.

|

|

Abuna-e |

危絵

あぶなえ |

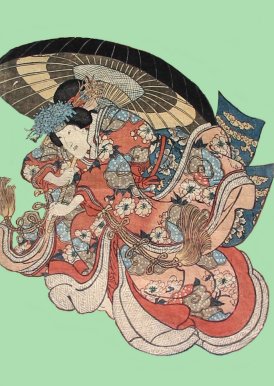

An erotic picture that is more suggestive than explicit.

The image to the left is from the Lyon Collection. The print is by Keisai Eisen. |

|

Abura-akago |

油赤子

あぶらあかご |

The abura-akago is a ghost-like creature which appears in the night in the form of a child which drinks the oil out of a burning lamp.

The image to the left is an illustration by Toriyama Sekien (鳥山石燕: 1712-88) from his Konjaku Gazu Zoku Hyakki or 'The Illustrated One Hundred Demons from the Present and the Past' from 1779.

What we don't know is origin of this creature.

Akago (赤子) means 'a new-born baby'. At one time it could also be pronounced as 'sekishi' when referring to children of the Imperial household, but that term is now obsolete. Abura (油) is oil.

"Abura-akago - eine Geistererscheinung, die als übernatürliche Flamme nachts in Häuser eindringt und dort die Gestalt eines Babys annimmt, um das Öl aus sämtlichen Lampen zu lecken. Allgemein gilt sie als Geist eines Toten, der zu Lebzeiten Öl gestohlen hat. In der Präfektur Shiga geht die Sage, es handele sich um die untote Seele eines Ölhändlers, der seine Ware im nahen Jizo-Schrein gestohlen habe und dem zur Strafe der Eingang ins Nirvana verwehrt wurde." Quoted from: Mythologien der Welt: Japan, Ainu, Korea by Michael Haustein, p. 3.

[Loosely translated: The abura-akago is the spectre of a dead Shiga prefecture oil merchant who would enter a home and take the form of a baby which would then drink the oil of a burning lamp. He was forbidden from ever entering Nirvana because when still alive he had stolen oil from a Jizo shrine.] |

|

Abura-sumashi |

油すまし |

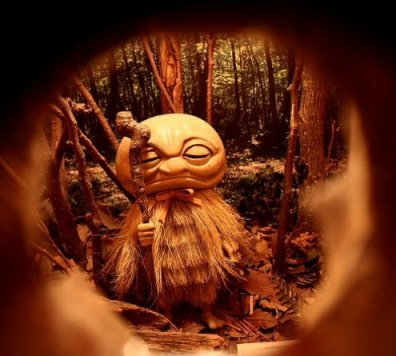

A goblin with a head which looks like a somewhat squished potato and which wears a clothes made of straw. Like the abura-akago shown above this creature drinks oil and may be the evil spirit of a dead oil trader.

We found the image to the left at Pinterest.

Abura for lamps was originally made from sesame grains. Later it was also produced from colza and cotton seeds. |

|

Age-bōshi |

揚帽子

あげぼうし |

A head cloth worn by women to keep their oiled hair clean from dust and properly coiffed during an outing. Very similar to the headdress worn by a bride. (See our entry on tsunokakushi.)

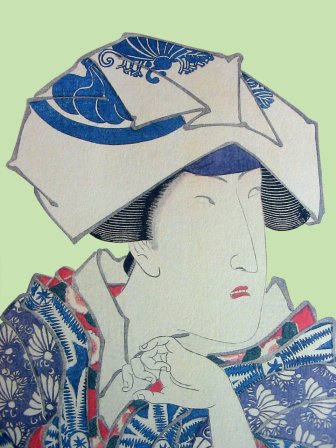

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Kiyonaga showing an actor in the role of a female samurai.

In volume 27 (1993, p. 98) of the Journal of the Costume Society, published by the Victoria and Albert Museum, it notes that the age-boshi was originally worn by women visiting sacred ground. Since it covered the front of their heads it was symbolically meant to hide their horns. "This had been retained, ironically as an essential part of the formal Japanese bridal costume."

Photo of a bride wearing a hood covering the age-boshi hiding her 'horns' from her mother-in-law. This was originally posted at Flikr by カランドラカス. We found it at commons.wikimedia.org/.

The Victoria and Albert displays a white wedding kimono on-line. They describe the marriage ceremony: "The bride wears a white under-kimono and heavy white outer-kimono known as a shiromuku [白無垢], shiro meaning white and muku meaning pure. This outer-kimono has a design of a large noshi, an auspicious ornament traditionally tied to goodwill gifts, the ribbons of which cascade down the front and back of the garment. The bride's hair is also elaborately styled and she wears a hood called a tsuno kakushi. This is meant to hide her two tsuno [角], or horns, to symbolize obedience to her husband. After the ceremony the bride exchanges the white outer-kimono for a brightly coloured one and joins her family and friends for the reception." |

|

It has been said that when a woman marries she leaves her old life and takes up a new one it is like dying. Not only is she dressed in white, but her face is painted white too. This is odd - from our perspective - because white is also the color of death. In The Japanese Mind: Understanding Contemporary Japanese Culture (2002, p. 206) it says in the section 'Laying out the Dead Person' "After the white kimono and makeup are put on, the deceased is laid out..." |

||

|

|

||

|

Ageha no chō |

揚羽蝶

あげはのちょう

|

"...a butterfly with its wings raised...was the alternate crest of Segawa Kikunojō."

The cloth covering the head of Segawa Kikunojō displays both of the crests used by this actor. This is a detail from an print from ca. 1822 by Kunisada.

According to Dower in his The Elements of Japanese Design (p. 4) the butterfly was used as early as Heian times as a favorite motif of the nobility. In time butterflies were used as family crests and were even popular during among warring factions during the bloodiest periods. (p. 88) [This to me seems like a bit of a paradox.] Dower also notes that "Among designs based on living creatures, the butterfly motif enjoyed by far the greatest popularity." (p. 89)

Jim Breen's site translates 揚羽蝶 as the Citrus swallowtail butterfly or Papilio xuthus.

Shu Suehiro gives the kanji as 並揚羽 for the same Papilio xuthus. I am not well enough versed to discern the differences - if there is one. He also refers to this particular butterfly as either the Chinese yellow swallowtail or the citrus s. b. as listed above. The image below to the left is shown courtesy of http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm.

Linnaeus gave us the name Papilio xuthus in 1767.

"In Japan, the Shosoin, the eighth-century Imperial treasurhouse at Todaiji in Nara, houses many objects using butterfly motifs. ¶ The butterfly signifies mysticism, through their undergoing metamorphosis and emerging from the chrysalis beautifully winged, while their gorgeous forms signify prosperity and success." "The young noblemen of the Heike (the military clan of imperial descent...) used the butterfly brilliantly as the symbol of their clan, using it on armor and helmets." Member's of Taira Kiyomori's faction and their descendants used the butterfly motif. The Ikeda clan used it. Oda Nobunaga bestowed this crest upon favorites.

Source and quotes from: Butterfly: 100 Royalty Free Jpeg Files, , by Toranari Shibe, published by the Bug News Network, 2006

In a play by Yukio Mishima set in the 12th century but actually based on a story by Kyokutei Bakin written in the early 19th Mishima has one of his characters Takama note: "The ship that's coming, rowing ahead of the pack, has a butterfly crest on the canvas." (p. 258) I note this for two reasons: 1) It refers to the militarization of the butterfly motif, something which we mentioned above, but 2) particularly because of the title of this book My Friend Hitler: And Other Plays, published by Columbia University Press in 2002. Hiroaki Sato, who translated this volume into English, notes that "Mishima completed A Wonder Tale: The Moonbow on the first of September 1969." It was published in a monthly in November and produced on the kabuki stage later that month directed by Mishima. "As he notes in one of his commentaries on this play, a single person writing and directing a kabuki play is a rare occurence." (pp. 244-5) Mishima also wrote a bunraku version which was produced by the National Theater two years later. (p. 245)

For more information on the butterfly motif go to our chō entry on our Bo thru Da index/glossary page. |

|

Ai |

藍

あい

|

Japanese indigo from the plant Polygonum tinctorium or dyer's knotweed - it is also referred to as tade ai: Indigo as a color can be produced from any number of plants, but here we are limiting ourselves to just one which was frequently used as a colorant in woodblock prints and fabrics. In Kosode: 16th-19th Century Textiles from the Nomura Collection: 16th-19th Century Textiles from the Nomura Collection by Amanda Mayer Stinchecum (pp. 202-3) notes that this plant grows throughout Japan, but especially in Shikoku. The leaves which contain indigotin and should be harvested in July through September and in November before flowering. The fresh leaves should be fermented or dried and/or composted.

In the earliest times the Japanese indigo leaves were chopped up in water. Later during the Nara-Heian periods they were fermented in water. During the Edo period they were fermented in lye water combined with other ingredients.

The resultant colors ranged from a pale to bright blue according to the number of leaves per quantity of water. Combined with other dyes a larger range of colors could be produced including lavender, fake purple and black.

In a web page posted by the University of Bristol "...Dr. David Hill of the School of Biological Sciences describes his quest to provide the modern world with a natural alternative to synthetic dyes." This is fascinating stuff. Especially his information about the source of indigo itself: "Indigo producing plants do not actually contain indigo but the leaves of these plants before they flower contain a substance which, when extracted from the leaf, forms indigo by absorbing oxygen from the air. Indigo is notoriously insoluble in nearly all commonly used solvents, and especially in water, so the indigo formed in the extracts settles out as a precipitate quite easily."

That might explain something I noticed while researching this subject. While searching for additional material to post here I ran across a beautiful page in English from a German language web site operated by Dorothea Fischer. After a brief correspondence she gave me permission to post the three images to the left. However, for a fuller and richer understanding of the entire process - especially as it pertains to fabrics, but clearly not greatly removed from the methods for producing early ukiyo indigo inks - I would urge you to visit her web page devoted to this topic. It is astounding.

http://www.lustauffarben.de/faerben-faerberknoeterich-englisch.html

I want to thank Ms. Fischer - and her friend Friedl who helped in our correspondence - for her contribution in creating this entry.

Ai is one of the colorants which will fade merely by being exposed to ozone even in the absence of all lighting. This fading occurs in both blue and green areas where ai has been mixed with other pigments. The same holds true for aigami which is listed below.

In Color Science in the Examination of Museum Objects: Nondestructive Procedures: Tools for Conservation by Ruth Johnston-Feller it says: "As this pigment fades under light exposure, it tends to become greener in hue."

|

|

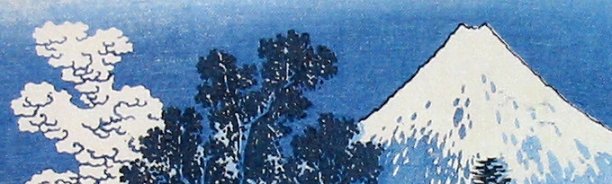

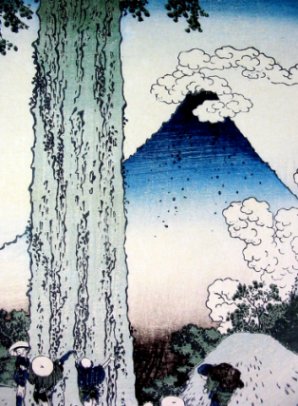

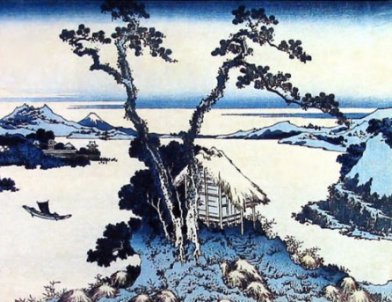

There is a fascinating scientific article published in 2006 by the Japan Society for Analytical Chemistryentitled: "Non-Destructive Identification of Blue Colorants in Ukiyo-e Prints by Visible-Near Infrared Reflection Spectrum Obtained with a Portable Spectrophotomer Using Fiber Optics". They inspected a set of prints from the "36 Views of Fuji" by Hokusai dated ca. 1830-33. Using a non-invasive technique they studied the use of aigami, ai (indigo) and the imported colorant Prussian blue. What they discovered was amazing - at least for me. The keyblocks were all printed with indigo "...while all color blocks were printed with Prussian blue." Prior to this study it had been assumed that all of the keyblock lines had also been Prussian blue, but clearly this was not the case. While this information may not interest everyone it is nevertheless remarkable for what it tells us about the production of what may be the most famous series of Japanese prints ever. The same exact technique was used for Hokusai's famous waterfall series Shokoku taki meguri. There were no exceptions. Both examples shown here are details from the Fuji series.

One last point: The scientists who wrote this article refer to the source of indigo as knotweed, i.e., Polygonum tinctorium, and not as dyer's knotweed as mentioned above. |

||

|

|

||

|

Aidono |

相殿

あいでん |

While working on my new web log at http://printsofjapan.wordpress.com/ I posted an entry on the stunning Shinto shrine at Miyajima near Hiroshima. One of the things which startled me was that the shrine was dedicated to four different goddesses. (It clearly shows my ignorance of Shintoism.) This bunching or sharing of a shrine amazed me, but apparently it is common. Raised on the Ten Commandments, one of which insists that I have no other god before me, had placed me in a particular mindset. Even temples dedicated to Apollo or Athena I always thought of as rather exclusive - whether they were or not.

That brings me back to our subject: aidono. There is some confusing information out there, but as best I can tell it means a hall containing more than one kami. "When several kami are enshrined together, the invited kami become subordinates to the principal kami (are enshrined to the right and left of the prinicipal kami..." (Quoted from: Historical Dictionary of Shinto by Stuart Picken, p. 25) Itsukushima, seen to the left, houses three goddesses who are the daughters of Susanoo and Benzaiten, one of the Seven Propitious Gods and the only female one. When grouped together it is referred to as an aidono-no-kami (相殿神). "This practice dates back to 649 C.E., when joint enshrinement took place at Kashima Jingu in what is now Ibaraki Prefecture. Katori Jingu is also in this category as is Kasuga Taisha. Joint enshrinement became especially popular during the Heian period (794-1185), when various forms of syncretism were developed." (Ibid.)

Below is Katori jingū (香取神宮), another shrine with multiple gods.

|

| In The Protocal of the Gods: A Study of the Kasuga Cult in Japanese History by Allan G. Grapard (p. 29) the shrine dedicated to Ame-no-kayane-no-mikoto and his consort Himegami "...was called aidono, a generic term designating a shrine dedicated to [these two gods]." Later Grapard translates aidono as "combined shrine" which is one of the literal translations possible of these two characters. (Ibid., p. 81) | ||

|

|

||

|

Aigami |

藍紙 あいがみ |

An early organic blue made from the dayflower. It fades quickly. Sometimes it fades to an olive gray. (See 'dayflower' listed Bo thru Da page.) 1

In Color Science in the Examination of Museum Objects: Nondestructive Procedures: Tools for Conservation by Ruth Johnston-Feller it says: "...the reflective curve for aigami (dayflower blue) is shown to have its own highly characteristic series of absorption bands, unlike any other blue to our knowledge."

Aigami is also known as blue anthocyanin. "Aigami was faded perceptibly after only two days of exposure to soft-white fluorescent lights, suggesting that 10 ³ flashes would probably cause perceptible fading of aigami in pristine Japanese prints... If photoflash exposure is to be limited to 0.01 of this, only about 10 exposures to xenon studio strobes could be allowed over the exhibit lifetime of the object." (Quoted from: Effects of Light on Materials in Collections: Data on Photoflash and Related Sources: Research in Conservation by Terry Schaeffer)

Edward Strange noted that early purple dyes used on Japanese prints "...was made by mixing Aigami (blue) and Beni (red), but now an imported purple is used." |

|

Aiguma |

藍隈

あいぐま

|

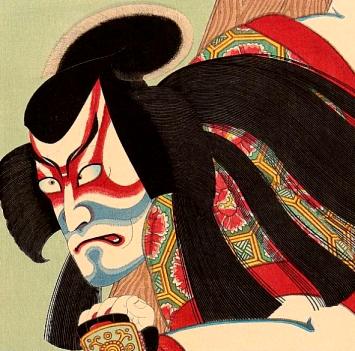

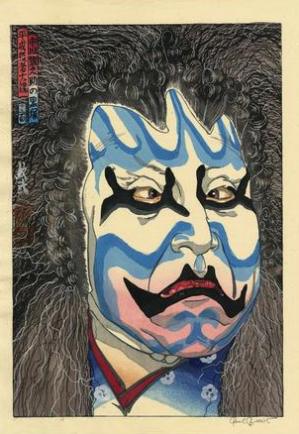

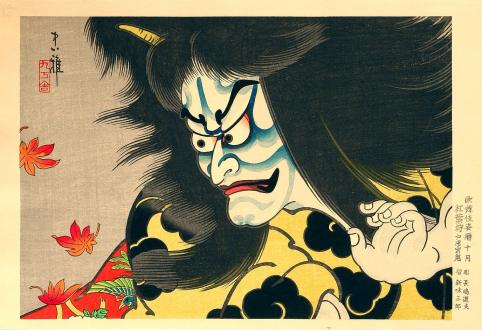

Indigo blue make-up used in kabuki. Samuel L. Leiter wrote: " "Blue shadows," a makeup term referring to a fearsome kumadori of blue lines on a white base. It is used to express wickedness and treachery." This makeup is worn often by villainous noblemen.

To the left is a detail from a Torii Kiyotada print. It shows the character Kagekiyo. Above is an image of the demon of Mount Togakushi. Below to the left is a detail from a Paul Binnie print of the ogress Iwate in the kabuki play Kurozuka. It comes from the Lyon Collection. |

|

Aizome |

藍染

あいぞめ |

Indigo dye - "Along with cotton another technical achievement that contributed to the popularization of yukata was aizome, literally “indigo-dyeing.” Aizome has a long history in Japan. The indigo plant was introduced from China around the second century, but the early dyeing techniques were very rudimentary, either the indigo leaves were directly rubbed on the material or the material was soaked in a liquid made from indigo leaves. The fermenting of indigo for a better dyeing process occurred in the Nara period (710-794), but this too was a relatively simple practice of placing indigo leaves in a earthenware jar and leaving it in the sun to ferment naturally. It was not until around the 15th century that heat was applied to cause the fermentation and aizome dyeing could be carried out all year long and not just in the summer months. By the mid-Edo period, aizome became popular among the commoners, produced in nearly every region of the country and even at home. Its popularization was in great part due to being an excellent dye for use on cotton, which also became common at this time, the two forming almost a perfect combination. The typical commoner’s kimono was indigo-dyed cotton with either a stripe or kasuri pattern, and stencil-dyeing was used for yukata. From the late 19th century, synthetic indigo became common and there are only a few workshops left today that still use indigo vegetable dye. The firmer texture of the cloth and the fresh clear color of the blue when dyed using true vegetable indigo is noticeably different from synthetic indigo..." Source: Karen Marks article on yukata worn during the Edo period.

We found the image to the left at Pinterest.

|

|

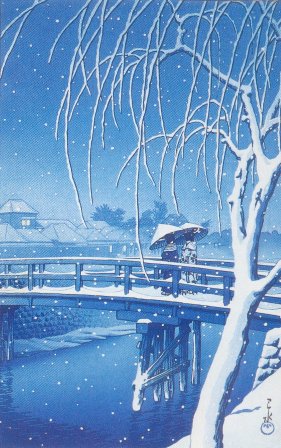

Aizuri-e |

藍摺絵

あいずりえ |

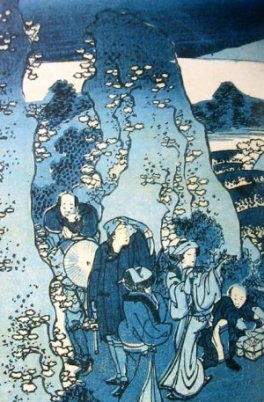

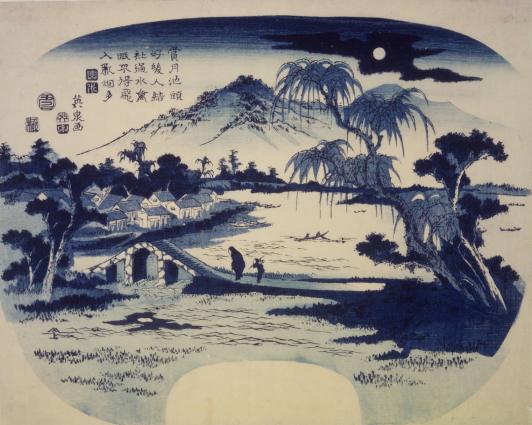

Images printed predominantly in shades of blue. The image to the left is by Eisen and dates from the first half of the 19th century and the Hasui below is from 1933. 1

|

|

In Matthi Forrer's book Hokusai (published by Rizzoli in 1988) he praises the boldness shown by Nishimura-ya Yohachi in marketing a series of prints using the costly, imported indigo dye. In 1831 the publisher announced the upcoming series in an advertisement in a novel by Ryūtei Tanehiko: "The thirty-six views of mount Fuji, by the old man zen Hokusai Iitsu, single sheet prints in blue impressions, each sheet featuring one design - now being published." (p. 263) "The note on thecoloring of the series is of particular interest. The term used in the original, aizuri, or 'indigo printing', in fact refers to a new pigment which only became available for woodblock prints close to 1830. However, there are examples of earlier use of this color, often called berurin [べルリン] burau (Berlin blue or Prussian blue). In the second half of the eighteenth century, for example, various painting manuals already make mention of it, sometimes adding that it was hard to come by, since it was imported through the Dutch. In woodblock prints, it appears by exception only, probably first on Osaka surimono from the mid 1810s and the first half of the 1820s. By 1829, the pigment was also available in edo and first used in surimono - where, of course, the matter of costs had not to be taken into serious consideration. Anyway, it still must have been a very precious material and that the commercial publisher Nishimuraya Yohachi dared to announce such a large series employing the novelty, makes the whole undertaking all the more prestigious. Almost by consequence, it may be assumed that the prints were aimed at a small and select audience, willing to pay the accordingly high price. The circumstance that, up to then, a series of pure landscapes of this scope had never been attempted - certainly a risky decision for any publisher to take - should only enhance our admiration for Nishimuraya." (p. 264)

"Prussian blue, I may add, seems to have been employed experimentally form the 1790s but was widely imported only form about the year 1829. The use of this pigment... began with privately issued surimono-prints, and was then extended to fan-prints (mainly) by the artist Eisen). The fashion soon spread to figure-prints as well and, within a year or so, to the landscape, in Hokusai's new series. For the aficionado of the earlier Japanese print, it may be difficult to understand why this 'foreign', mineral colour should so suddenly usurp the place of the delicate and lovely blue pigments that had been favoured hitherto - in. for instance, the prints of Harunobu and Utamaro. The first reason for its adoption was simply the characteristic Japanese love for new things, and their near worship of imported goods. At the same time, the native, vegetable dyes were often fugitive, and blue was particularly susceptible to fading. (Today, indeed, collectors and museums often refuse to lend their early pirnts for extended exhibition, for this very reason.)"

Quoted from: Hokusai: Life and Work, by Richard Lane, E. P. Dutton, 1989, pp. 184-5.

"Prussian blue was not first introduced in Edo. In the 1820s Japan was still closed to foreign trade, and European products all entered Japan through the Dutch settlement in the port of Nagasaki. The first use of Prussian blue on a woodblock print is on the cap of the immortal in a privately published surimono printed in Osaka in the spring of 1825..."

Quote from: Japanese Woodblock Prints: A Catalogue of the Mary A. Ainsworth Collection, by Roger Keyes, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, 1984, p. 42.

Roger Keyes says that the first use of Prussian blue on a woodblock print may have shown up on the cap of an immortal riding a crane. This appears on a surimono by Nagayama Kōin (長山孔寅) "...printed in Osaka in the spring of 1825". Ibid.

In the catalogue entry #439 on p. 185 of the Ainsworth collection Keyes notes that this print was produced to honor the retirement of the actor Nakamura Utaemon III. This "...print is of special historical interest since Prussian blue seems to be used ont ehimmortal's cap and this color, which is used in so many landscape prints, is said not to have been introduced in Edo until 1828."

Sebastian Izzard in his Kunisada's World (p. 29) provides additional information: "A feature of these prints is the occasional use of Bero-ai - that is, Berlin, or Prussian, blue. The exact date when the synthetic pigment was first imported into Japan by the Dutch is not known. The ukiyo-e scholar Yoshida Teruji quotes an Edo bookseller and haiku poet Seisōdō Tōho as saying in a book of essays that Prussian blue was introduced in 1829 (Bunsei 12) by the artist Ōoka Umpō (1765-1848), who used it in a surimono. Soon afterwards it was taken up by all the surimono artists. Seeing the popularity of these prints, the fan-print publisher Iseya Sōbei first used the pigment the following year on prints by Keisai Eisen. ¶ While Tōho's reminiscence may be true for completely blue-printed works (aizuri-e) - an aizuri-e fan print by Kunisada is seal-dated 5/1830... Bero-ai in fact appears to have been used even earlier, but only in small areas of design and normally to delineate luxury products and accessories. In Kunisada's work the earliest such use appears to be in a painting of 1822-23... Kunisada's fan print of 1825... and an Osaka surimono of the same year have the blue, again in limited areas. The blue is also found on prints collected by Philipp Franz von Siebold, a member of the Dutch trading mission at Dejima island from 1823 until 1829. The pristine quality of these prints is such that von Siebold probably acquired them directly from the publishers when he made an official visit to Edo in 1826... ¶ From all the evidence it seems likely that when first brought in by the Dutch, the synthetic pigment was a luxury, high-priced import. This would explain why it is first found on paintings and then on elaborate, surimono-style prints created for the connoisseur market..., and in small areas of expensive early editions of full-size prints... With the success of the color and its import in greater amounts, the price would have fallen, enabling publishers to use it for monochromatic blue prints."

Henry D. Smith II in an article about blue dyes in Japanese prints wrote: "...it seems clear that the quality of indigo abō and the techniques used to print it were improving throughout the Bunsei period, prior to the regular use of Berlin blue in Edo nishiki-e after 1830.This improved use of natural indigo effectively marks the first stage of the 'blue revolution' in Japanese prints. A striking example is the Kunisada triptych 'Mokuboji bosetsu' (Evening snow Mokuboji)... which has been dated circa 1820 on stylistic grounds by Sebastian lzzard. According to the scientific analysis of Shimoyama Susumu and Noda Yasuko, the several shades of blue on the women's kimonos and the bokashi gradations on the water are all printed in natural indigo." The effect is so striking that it is easy at first glance to mistake it for Berlin blue, as I myself did in an earlier version of this article." At any rate, examples like this clearly demonstrate that by the early 1820s, natural indigo could be printed to much more striking effect than ever in the past."

This triptych from ca. 1820 in the collection of the Rijksmuseum voor Volkenkunde in Leiden was originally believed to have been colored by Prussian blue, but it dates to early stylistically for that. A scientific analysis of the blues in this composition show that the publisher used newly improved techniques using indigo dyes.

Smith in his essay 'Hokusai and the Blue Revolution in Edo Prints' postulated that the first aizuri-e print was of a fan published by Iseya Sōemon in 1829. Smith that this Eisen print in the Brooklyn Museum and meant to represent a Chinese landscape. Shindō Shigeru, a Japanese expert on Kunisada, thinks that that artist was the first to produced an aizuri-e.

Smith believes that the print by Kōin detailed above was definitely not the first time Berlin blue had been used by a printmaker. He thinks that the first one may have appeared around 8 years earlier in 1821 on a print by Hokushū in Osaka. [This writer remains highly skeptical of this earlier date.] However, Smith is on more solid ground when he hypothesized that single tint Berlin blue was used as early as 1824 in illustrations for an ehon, Nokinarabi musume hachijō (軒並娘八丈). |

||

|

|

||

|

Ajirogasa |

網代笠

あじろがさ |

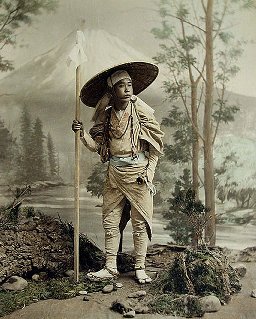

A bamboo or wicker hat worn by pilgrims.

The image to the left is a detail from a photo taken by Kusakabe Kimbei (日下部金兵衛: 1841-1934). It was posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Catfisheye.

"A pilgrim wears a bamboo hat (ajirogasa), a kosode, and obi, usuallv ol ramie, the sleeves of the kosode tied out of the way with a tasseled cord. He has leggings (kyahan) \ and waraji sandals. He uses a staff to aid his journev and to startle insects to prevent them from being crushed. Lay people wore this costume, its uniformity uniting all classes in their faith." Quoted from: What People Wore When: A Complete Illustrated History of Costume from Ancient Times to the Nineteenth Century for Every Level of Society by Melissa Leventon, p. 193.

"To make the hat waterproof it could be impregnated with persimmon tree sap (kakishibu), which turned it a dark orange-brown. (Ibid., p. 332) |

|

Ajisai |

紫陽花

あじさい |

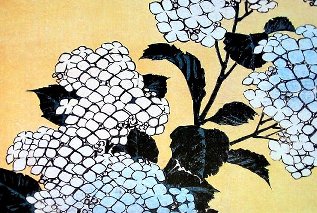

Hydrangea

Above is a detail from a Hiroshige print from the 1830s.

The photo to the left was provided by Shu Suehiro at Botanic.jp. Gorgeous, isn't it?!

From 1834-36 a 26 volume guide to the famous sites of Edo was published. It was compiled by Saitō Gesshin, a local district official and based on work started by his grandfather and father. It was the best guide of its time. "During the sixth month Gesshin decorated the outside of his house with hydrangeas (ajisai-tsuri)... [He] continued [this practice] well into the Meiji period. This event took place on the first day of the sixth month of the lunar calendar, the start of the most severe summer heat. Many pictures of the ajisai-tsuri have been drawn by Kaburagi Kiyokata (1878-1972), who had a special liking for hydrangeas. Kaburagi even named his personal residence 'Hydrangea House.' This connection between the sacred nature of this flower and daily life seems to have been felt strongly by downtown residents during the Edo and Meiji periods." Quoted from: Edo Culture: Daily Life and Diversions in Urban Japan, 1600-1868 by Nishiyama Matsumosuke, p. 87. Note: The British Museum says that Kaburagi died in 1973 and not 1972. |

|

In the 1922 Journal of the Arnold Arboretum (p. 243) from Harvard there is a list of several names used for Japanese hydrangeas. The author, Ernest H. Wilson mentions the Hosoba-amacha it seems is only used in this publication and cannot be found anywhere else. Wilson does say that the term he heard the most was for the Yama-ajisai (山紫陽花) or Mountain hydrangea (Hydrangea serrata). Below is a photo of this plant supplied by Shu Suehiro at Botanic.jp.

Wilson notes that in the West "It was Thunberg, in 1784, who gave the first binomial names to these Hydrangeas but he referred to them wrongly to the genus Viburnum." Siebold called the same plant the Hydrangea Thunbergii. The hydrangea made its first appearance in Europe thanks to Sir Joseph Banks in early 1789. These plants were brought from China. The Frenchman Jussieu referred to this genus Hortensia as the Rose of Japan. Kaempfer was the first Westerner to mention it in 1712 where he called it by such names as vulgo Adsai and Adsikii.

In 1863 Bairyu (梅笠) wrote this death poem: O hydrangea - / you change and change/ back to your primal color. This appears in Japanese Death Poems by Yoel Hoffman. Hoffman notes that "The common name for the flower is nanabake, 'seven changes,' as it changes color seven times, from shades of green to yellow, blue, purple, pink, and finally back to green. This flower was introduced to the West by the German doctor Philipp Franz van Siebold (1794-1866)..." (pp. 139-40) Of course, this information does not agree with what we posted above that it was Banks who introduced the plant five years before Siebold was born. |

||

|

|

||

|

Aka-e |

赤絵

あかえ |

Images printed predominantly in shades of red. These prints were often sold door-to-door by monkey trainers in the 18th c. as talismans against smallpox. This is interesting because monkeys were often kept in stables to ward off horse diseases. It is even said that sometimes samurai who wanted to spy on their enemy's camp would pose as monkey trainers just to gain admittance.

Also referred to as hōsō-e (疱瘡絵) or smallpox pictures. Originally used in China these were adopted by the Japanese and often featured images of Shoki, the Demon Queller. His image was also shown on the fifth day of the fifth month or Boy's Day as a similar talisman for warding off evil spirits.

As you can tell from the detail of the Shigemasa (重政) image to the left a hōsō-e can illustrate something other than a Shoki. In this case it is a Daruma and an owl and an object we can't identify yet. We now know, as of December 2017, that the unidentified object is a dendendaiko. This information was provided to us in February 2011 by David Parfitt, but somehow got lost at that time through some error of our own. We are now correcting that mistake and have Mr. Parfitt to thank for this information.

Rebecca Salter - she is cited twice below - noted that Daruma and children's toys were often represented on prints meant to drive away evil kami forces. They were more lighthearted and brave in the face of the disease.

"The person suffering from smallpox and those caring for him dressed in red to appease the Hosogami. In addition, 'red prints' or hoso-e prints, paper wall amulets were posted at the first hint of smallpox to propitiate, avoid, and/or banish the illness. They're called 'red' because that is the primary color of these prints. If no print is available, red banners may suffice. Following the patient's recovery, these prints were traditionally ritually burned or floated down rivers to signal the departure of the spirit. Extremely few survive and these are now extremely valuable collector's items." Quoted from: Encyclopedia of Spirits: The Ultimate Guide to the Magic of Fairies, Genies, Demons, Ghosts, Gods & Goddesses by Judika Illes. |

|

Aka-e "..."became particularly popular during the smallpox epidemics of 1830, 1838 and 1849. The prints were produced in just one colour, red from benibana, safflower) because there was an old wives' tale that if you dressed a smallpox patient in red, the attack would be mild. It was believed that red was an apotropaic colour, that the smallpox demon liked it so much he would pleased at the sight of red garments and deal gently with the wearer. In some parts of Japan the patient was even painted with rouge to mollify the smallpox kami. Gohei (white sacred paper strips) used in Shinto rites, were made instead out of red paper and placed near the patient on the threshold of the house. Paper was dyed red, oiled and used to colour the light cast by the sickroom lamp, by which an examination (beginning with the feet) was made." Quoted from: Japanese Popular Prints: From Votive Slips to Playing Cards by Rebecca Salter, pp. 120-121.

"The smallpox kami was said to be especially fond of babies.... Woodblock prints came to play a part n this process as 'charms' to be pasted at the door to keep teh malign kami away, as gifts to teh suffering patient and as illustrated health advice. Books were still relatively expersive so, particularly in teh case of measles prints, advice was offered in the format of the cheaper single sheet print. Artists including Utamaro II, Kunitora, Kuniyasu adn Kunimaru produced smallpox prints; Yoahitora, Yoshifuji and Yoshitoyo produced measles prints." (Ibid.)

"The delivery from teh disease was marked by several rituals. The presents of toys and prints which neighbours had brought were burned (one reason why few prints remain), celebratory sticky rice with red beans (the red pleased the kami) was distributed to neighbours and the recovered patient was at last allowed to bathe in hot water fragranced with bamboo grass leaves (sasa)." (Ibid., p. 122)

See also our entry on hōsō .

Aka-eis also the term used for iron-red enamel decorations on Japanese ceramics such as Arita ware. Below is a bowl with this kind of decoration from ca. 1670-90. It is from the collection of the Gardiner Museum in Toronto.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Akane |

茜

あかね

|

Madder red made from the Rubia argyi root.

"Shounko, the fifth Lord Maeda, also took a great interest in a red dye called akane, made from the roots of a grass that grew wild in the province of Totomi and in lesser quantity around Kyoto. Known since ancient times, it was a more yellowish scarlet color than beni and the other brilliant reds used for ceremonial wear, and because it could be cheaply produced it was much worn during the lean days of early Edo. In fact, it became so notoriously cheap at that time that the younger generation soon began to ridicule anyone who wore it, and eventually the secret of its manufacture appeared to be all but lost. A variation using beni and a yellow dye—kuchinashi or kariyasu—also called akane, produced a more pinkish red but was rarely used on the best silk. ¶ Anxious to recover the secret of true akane, Maeda sought out a family of dyers who still remembered it and took them under his protection. Then the akane dyed in Kaga again became popular, especially for armor and flags." Quoted from: Japanese Costume & Makers: And the Makers of Its Elegant Tradition by Helen Minnich.

Flowering madder plant from the web site run by Shu Suehiro.

The photo to the left (below) comes from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, their CAMEO project. |

|

"As fashion became gayer during the Edo period, red linings and underkimono superseded white. Saikaku wrote that a Kyoto woman, was known by the red lining of her kimono. For a time, red was seldom worn in outer kimono except by samurai women, because few as yet had the courage to display such brilliance in the full light of day. Daughters of samurai, and even the older members of the family, liked to wear red because it was a brave color but also because they thought it extraordinarily becoming.... ¶ "In the gay days of Genroku, ladies often copied the classic Ashikaga fashion of wearing brilliant red hakama (divided overskirts) with a white kosode. This is still the costume of Shinto priestesses, and even maidservants at open-air teahouses still remind us of it with their bright red aprons. ¶ Akane, a very different, purplish red, was made from the roots of a wild grass that grew in the province of Totomi and was also found occasionally in the vicinity of Kyoto. Discovered as early as Fujiwara, and much worn in Ashikaga, it became so common in the early frugal days of Tokugawa because of its cheapness that one who wore it in Genroku's flashy days was an object of scorn and ridicule, especially to the younger generation. So unpopular, in fact, did it become that it would have been lost, except that Lord Maeda of Kaga Province, with his special interest in "plum-colored" dyes, took the family who knew its secret under his special protection."

The CAMEO project at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston tell us that the terms Rubia akana and Rubia argyi are the same thing. This plant grows to about 39" tall and that its flowers are hermaphroditic. |

||

|

|

||

|

Akatonbo |

紅蜻蜓 or 赤蜻蛉

あかとんぼ |

Red dragonfly -

In 1921 Miki Rofū (三 木露風: 1889−1964) composed a a poem called 'Aka tonbo' which was set to music and sung by dearly all school-age children.

The photo to the left was posted at wikimedia.com by Hans Hillewaert. |

|

Akahime |

赤姫 あかひめ |

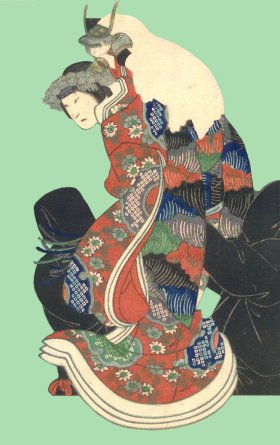

"Red princess": There is a sub-subcategory of female theatrical characters referred to as akahime. "The term is used because so many kabuki princesses and samurai daughters wear red, long-sleeved kimono.... The costume, a kabuki invention having no relation with what actual princesses wore, consists of a robe (uchikake) worn over a kimono of red-figured silk or crepe on which designs of flowers, cherry blossoms, chrysanthemums, clouds, a pattern of long-tailed birds called onagadori, and flowing water are embroidered in gold and silk. The kimono is held together by a brilliant gold brocade obi; at the rear of the obi is a long hanging bow. The wig is a fukiwa type with a large silver flower comb attached to it."

Quoted from: New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of kabuki jiten, compiled by Samuel L. Leiter, 1997, p. 8.

Professor Leiter also pointed out that such a princess "...is typically a physically weak, emotionally vulnerable young lady... She is normally in love with a handsome young lord."

Ibid.

The top image to the left represents Sakurahime by Toyokuni III and the one below is from a Yoshitaki print featuring Yaegakihime. Click on the numbers to the right to see the full images.

Professor Leiter published an Historical Dictionary of Japanese Traditional Theatre in 2006 (published by Rowman & Littlefield, p. 33) in which he gave a more expansive definition of an akahime. He described this figure as "frail, sensitive, and beautiful..." and noted that her red gown could also be "...pink, white, or pale purple..." These women "...represent a purely fictional ideal of such high-placed females..."

Akahime "...are not the off spring of royal blood, but rather the pampered daughters of daimyo and ranking samurai. They are so named after their bright red long-sleeved kimono and glittering silver tiara. Akahime are usually played as rather static characters, who often sit with their left hand withdrawn inside their kimono sleeve, which is held out to the side, and their right sleeve held across their chest. They tend to be rather reticent girls who speak only rarely, until passion and a sense of duty move them to heroic heights."

Quoted from: A Guide to the Japanese Stage: From Traditional to Cutting Edge, by Ronald Cavaye and Paul Griffith, published by Kodansha International, 2004, p. 62.

Adolphe Clarence Scott in The Kabuki Theatre of Japan (reissued by Courier Dover Publications, 1999, p. 138) that the akahime wears "...a richly embroidered kimono of scarlet silk with a long flowing suso [裾] or hem.... and worn regardless of time, season or place." Later he adds that "...the hime roles are regarded as the high water mark of acting for the onnagata."

|

|

Aki no nanakusa |

秋の七草

あきのななくさ

|

The Seven Flowers of Autumn: Merrily Baird in her Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design (p. 97-8) calls these the Seven Grasses of Autumn. Properly speaking that is correct because kusa, 草, is translated as grass. I am pointing this out because you might find both versions when you are doing research on your own and both are interchangeable.

Baird states: The "...theme is native to Japan, illustrative of a love of seasonal motifs in general and of autumn in particular. With a pedigree that dates to the eighth-century Manyoshu poetry collection, it is also one of hte most enduring themes in Japanese poetry and art. ¶ As established in the Manyoshu, the Seven Grasses of Autumn were bush clover (hagi), pampas grass (susuki, obana), arrowroot (kuzu), wild carnation (nadeshiko), ominaeshi, fujibakama, and the bellflower (kikyo, asagao)." Chrysanthemums and morning glories were not among the original groupings, but in time became substitutes. ¶ The uses of the Seven Grasses of Autumn in art developed in the Heian era. It achieved its greatest prominence in the Momoyama period, when the theme - thought to be particularly appropriate for goods used by women - was employed extensively on a typ of lacquer associated with the Kodaiji Temple in Kyoto."

Cautionery note: I have tried to post images of each of the plants in the original list. Because of problems of nomenclature, not to mention translation, several of these, if not all, may be somewhat off the mark. Please bear with me on this one. If you see mistakes let me know, but be prepared with proof.

|

|

The first image shown above just above the kanji is that of Thunberg's bush-clover (盗人萩): Desmodium oxyphyllum. The second one, the one in the middle above is susuki (薄): Miscanthus sinensis. Third is the kuzu (葛): Pueraria lobata. It is shown above just below the kana for aki no nanakusa. The fourth one is particularly difficult for me to pin down. Is it the Dianthus japonica? Or, is it some other member of that family? Until I know otherwise I will go with the D. japonica for the nadeshiko example. It can be seen at the top in the box above to the right. The fifth one, the ominaeshi (女郎花) - Patrinia scabiosaefolia - is the yellow flowering plant shown above to the right. The sixth one is the fujibakama (藤袴) or Eupatorium japonicum. That plant is shown in this section immediately above. The last one is the kikyō (桔梗) or Platycodon grandiflorum is also referred to as the Chinese bellflower. This can be seen below and on our kikyō entry on our Kesa thru Kodansha index/glossary page.

All of these images are being shown courtesy of http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. It is an absolutely wonderful site and you should definitely visit it. Easy to navigate, full of wonderful imagery and rich with information in both English and Japanese. |

||

|

|

||

|

Aku |

悪 あく |

Evil, bad or inferior - a mark branded onto the foreheads of convicts in Edo around 1670. For more about tattooing as punishment go to our Bad Boys and Their Tattoos - page 4. |

|

|

悪婆 あくば |

In kabuki, according to Samuel L. Leiter an akuba is a 'bad old woman' or a 'female villain'. "These un-lady-like roles, which despite the term - are normally not old but middle-aged, became popular during a period of increasing decadence in the nineteenth century. They bear nicknames, use coarse, slangy Edo speech, and dress boldly. They earn their bread by blackmail, theft, gambling, and pandering, although the plot usually reveals that their underlying motives are decent. Often, they kill themselves at the end. The first example is said to have been Mikazuki ("Crescent Moon") Osen... followed by such popular characters as Dote ("Embankment") Oroku... Unzari ("Disgusted") Omatsu... Onigami ("Demon") Omatsu... Kirare ("Scarface") Otomi... and Onna ("Female") Sadarukō (based on a villain in Kanadehon Chushingura)... Such characters usually wear a kimono with the benkei gōshi pattern (small blue oblong checks) and a collar over which black satin has been sewn. A plaid obi is worn with its knot tied at the breast, and a short, blue jacket (hanten) with a white pattern completes the outfit. The wig has a pony tail and is parted into two tufts at eh forehead..." |

|

Akushō |

悪所 あくしょ |

A dangerous spot; a house of ill repute; a bad quarter.

According to the Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary, 1954, p. 20 akushō written with different kanji (悪性) translates as evil nature or evil-disposed or licentiousness, profligacy, lewdness, etc. |

|

Rachel Payne wrote: "From its origins as a side-show for prostitutes in the early seventeenth century, kabuki flourished during the Edo era (1603-1867) to become one of the mainstays of urban popular culture. For the chōnin townsmen, who were greatly limited bythe Edo class hierarchy, theaters and the pleasure quarters provided welcome fun and fantasy, and occasional visits there by samurai were also usually reluctantly permitted by the authorities. However, restrictions were applied when the corrupting influence of these so-called akusho (wicked places) grew too strong. Takahashi... describes akusho as 'sites of negotiation between the subordinate classes seeking freedom and the ruling classes trying to impose control'. Popular theater was accepted as a necessary evil, but the price it paid for governmental tolerance was a strict set of regulations covering all aspects of the professional and private lives of actors. These were intended to force them to behave in a manner appropriate to their low social rank. For, although officially despised as hinin (non-human), successful actors earned huge salaries and enjoyed star status among fans."

"For city dwellers these two areas [the Yoshiwara and the kabuki theaters] were the worlds of pleasure and fun, a forbidden sphere outside restrictive society, often termed akushō (evil places) or chikushō (Buddhist realm of beasts), while the popular term was gokuraku (paradise)." Quoted from C. Andrew Gerstle in A Kabuki Reader: History and Performance, p. 90.

"The akushō were sites of negotiation between the subordinate classes seeking freedom and the ruling classes trying to impose control." Quoted from Yuichirō Takahachi in A Kabuki Reader: History and Performance, p. 141. |

||

|

|

||

|

Amagasa |

編み笠 あみがさ |

A braided hat: Cecilia Segawa Seigle noted the construction of teahouses along the 320 foot long zig-zag road leading from the Primping Hill to the Great Gate of the Yoshiwara. Men would stop at these to freshen up and some would even change their clothes to impress the ladies. "Some of these establishments were amigasa-jaya (woven-hat teahouses) where samurai clients could rent a hat to make themselves less conspicuous." Quoted from: Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1993, p. 64. (The jaya or chaya kanji is 茶屋.)

The image to the left from an inset in a Kuniyoshi print shows one type of braided hat. Itinerant monks or komusō (虚無僧) wander the countryside wearing tengai (天蓋) or "basket-shaped woven rush hats", carrying curved bamboo flutes or shakuhachi (尺八). However, not everyone so attired is actually a monk. Sometimes theatrical/historical figures like the Soga brothers or a character from the "Tale of the 47 Loyal Retainers" disguise themselves in these outfits. In fact, even lovers on a tryst were portrayed this way by Harunobu and Shunshō. According to one source there was "...vogue for komusō prints about 1770..." because of the popularity of a dance sequence "...incorporated in the play Sono Sugata Shichi-mai Kishō (Her Lovely Form: A Seven-page Written Pledge)..." Quote from: The Actor's Image: Print Makers of the Katsukawa School, Princeton University Press, Timothy Clark and Osamu Ueda with Donald Jenkins, 1994, p. 152. |

|

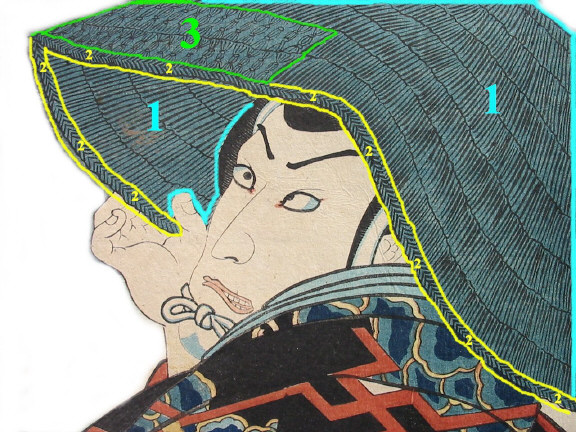

The detail of below is from a Toyokuni III print which we sold. We doctored the image to highlight the different woven areas of the hat. This particular type of amigasa is referred to as a 深網み笠.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Amagatsu |

天児

あまがつ |

"A girl received a dagger (mikabashi [みかばし?]) at birth, as a protective talisman. Another protective device was the godchild (amagatsu), a doll that served the same purpose as [a] purification doll... The child was supposed to transfer into the doll any evil influence that could harm her." She would keep the doll until about her third year. Also, many dolls served the purpose of absorbing evil spirits in early Japan.

Quoted from: The Tale of Genji, by Murasaki Shikibu, translated by Royall Tyler (ロイヤル・タイラー), published by Viking, vol. 1, 2001, p. 350, note #7.

This translation by Royall Tyler is a remarkable accomplishment and a great source for additional material about the world of the Heian period.

The purification ceremony was referred to as the harai (祓い).

According to Nancy Moore

Bess and Bibi Wein in Bamboo in Japan (Kodansha International, 2001,

p. 152) these dolls had "...a T-shaped body of bamboo..." |

|

Jane Marie Law in Puppets of Nostalgia published by Princeton University Press in 1997 (p. 35) said: "Amagatsu [heavenly infants] in Heian Japan and continuing until the present, various dolls or effigies have been widely used as substitutes for fetuses, infants, and children to protect them from evil influences and disease."

"They are generically called o-san ningyō (birthing dolls)."

These figures are also referred to as katashiro (形代) or 'substitute figures'. Aston tells us that kata-shiro means 'form-token'. A few days before a special purification ceremony held twice a year in Tokyo true believers would visit a shrine to the sea gods and there they would purchase a katashiro "...that is, a white paper cut into the shape of a garment. On this the person to be purified writes the year and month of his birth and his or her sex, and rubs it over his whole body. When he has thus transferred his impurities to the paper he returns it to the shrine. All the katashiro which are brought back are packed into two sheaths of reed and placed on a table of unbarked wood. They are then called harahi tsu mono, or things of purification. Finally they are put into a boat which is rowed out into the sea, and they are thrown away there." Quoted from: Shinto: (the Way of the Gods), by William George Aston, Longmans, Green, and Co., 1905, p. 263.

Sara Francis Fujimura in the January 2006 issue of "Appleseeds" noted that the amagatsu given to a boy at birth stayed with him until he became an adult and then it was burned and the ashes were buried. Baby girls received hōko (這子). These had "...a soft, white silk body, and a wooden head and spine..." which they kept with them into married life. In ancient times the owner would blow on the doll or rub it against their body to transfer evil spirits from them into this substitute object. Sometimes they would throw them into river to wash away the bad luck.

In Ningyō: The Art of the Human Figurine Shigeki Kawakami states that amagatusu were being made by Heian times. "There are no extant examples of amagatsu from before the Middle Ages, but even those made during the Edo period remained faithful to the original designs. Amagatsu are made with cylindirical sticks arranged into a T-shape - expressive of a body and arms - onto which a white, silk cloth-covered head is attached." Kawakami continues: "Hōko are white silk dolls stuffed with cotton. Their production is detailed in a work about childbirth form Muromachi period entitled, O-san-no-Kishiki. The name hōko means 'crawling baby,' and its form represents crawling posture of an infant." These dolls were traditionally made on the same day as the birth. "By the time of the Edo period, these two types of figurines were treated as a pair; amagatsu came to represent boys, and hōko, girls." (Japan Society, Inc., 1995, p. 11)

In The Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon (translated by Ivan Morris, Penguin Books, 1979, footnot 229, p. 314) there is an interesting refence to a royal birth: "The delivery of a Heian Empress, however, was attended by a good deal of impressive ceremonial. Religious services took place for several days in the Imperial birth chamber, and the birth itself was witnessed by numerous white-clad courtiers. Thsi was follow by ceremonial bathing, after which a sword and a tiger's head were shaken in front of the infant and rice scattered about the room - all to keep evil spirits at bay."

In A Tale of Flowering Fortunes it states that in the 11th century when aristocrats died "Relatives customarily placed human figurines, of the kind used in purification rituals (katashiro or amagatusu), in the coffin." Quoted from: A Tale of Flowering Fortunes: Annals of Japanese Aristocratic Life in the Heian Period, by By William H. McCullough and Helen Craig McCullough, Stanford University Press, 1980, p. 679, footnote 14.

A generic substitute form is the nademono (撫物) or a 'thing to be rubbed.'

If the significance of this doll hadn't been made clear enough by now this passage from Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852-1912 by Donald Keene should drive the point home. It is about the child who grew up to be the Meiji Emperor. "After the umbilical cord has been cut, the baby was given his first bath. In keeping with the old custom, the water had been drawn from the Kamo River and was mixed with well water. For the next few days, until the baby was given swaddling clothes, he was dressed in an undershirt and a sleeveless coat. His bedding was laid on a katataka (a thick tatami that has been sliced in half on the bias, leaving one end much higher than the other) in the main room of the little house where he was born. A pillow was placed at the high end of the tatami to the east or to the south, and it was guarded by two papier-māché dogs facing each other. Between the two dogs were placed sixteen articles of cosmetics. Behind them was a stand on which the 'protective dagger' the prince had received was placed along with an amagatsu doll also wrapped in white silk but with red silk pasted to the ends of its arms and feet." |

||

|

|

||

|

Amagoi |

雨乞い or 雨請い

あまごい |

Praying for rain - "Prayers for rain may be addressed to any kami... Certain shrines are good for rain requests, and the Shinano togakkushi jinja in Nagano receives requests from all over the country asking for prayers to be offered and distributes sacred water to farmers to induce rain on thier fields." During droughts prayers are directed to the thunder god. Some places have annual festivals while others offer prayers every four or five years. Special dances are performed - some lasting for days. Sometimes people try to provoke the kami by waving torches around or "...throwing polluting materialsuch as cattle bones into waters usually regarded as sacred, such as lakes around Mt. Fuji." (Source and quotes from: A Popular Dictionary of Shinto by Brian Bocking)

Make sure you look at ame or rain further down this list.

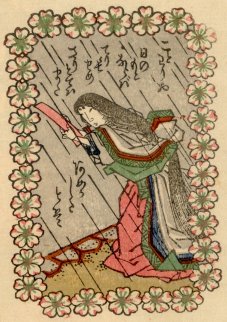

To the left is a detail from a Kunisada print showing the poetess Ono no Komachi (小野小町) praying for rain.

In Ancient Buddhism in Japan by de Visser has a section which on which sūtras to read to bring rain: "In A.D. 642 (first year of the reign of Empress Kōgyoku... at the time of a great drought, the Shintō rites of killing horses and cattle as a sacrifice to gods of various shrines and prayers to the River-gods, as well as the old Chinese custom of changing the market-places, had been without any result. Then Soga no Oho-omi (Emishi) said: 'The Mahāyāna sūtras (Daijō kyōten, 大乘經典) ought to be read (by way of extract) (tendoku) in the temples, our sins repented of (kekwa, 悔過...) as the Buddha teaches, and thus with humility rain should be prayed for.' "

It should also be remembered that just as there were prayers to bring on the rains there were prayers to stop it. |

|

Ama no hashidate |

天の橋立

あまのはしだて |

One of the 'Three Great Views of Japan' along with Matsushima (松島) and Miyajima (宮島). Ueda Akinari (上田秋成: 1734-1809) and his wife were walking to a hot springs when the passed Ama no hashidate. "At Iwataki they hired a small boat to take them to Amanohashidate on the opposite shore, and while they sand bar came into view overgrown with pine trees twisted into weird shapes Akinari related to his wife the legends surrounding the place. Amanohashidate was said to be the remnant of the Floating Bridge of Heaven, upon which the deities Izanami and Izanagi had stood when they stirred up the ocean and created the islands of Japan. Nevertheless, although Akinari appreciated the tradition, he was too much of a realist not to be sceptical. He did not think the scene really looked as though it had fallen from heaven, and he decried people who lead others astray with ill-founded tales." Quoted from: Ueda Akinari by Blake Morgan Young, p. 73.

The photograph to the left is from Wikipedia.commons. The Hiroshige print is from the Chazen Museum of Art.

|

|

Amano Iwato Shrine |

天岩戸神社

あまのいわとじんじゃ |

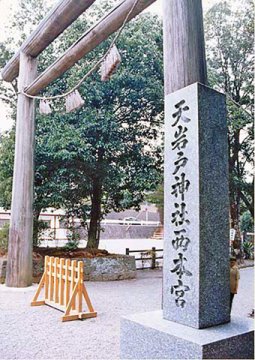

A shrine located 8 km from the town of Takachiho ( 高千穂峡) in Kyushu. The shrine is divided in two by the Iwato River. On one side is a Shinto structure open to the public while on the other side of the river is another shrine building near the cave where the sun goddess, Amaterasu, hid herself away plunging the universe into darkness. There is another cave nearby, the Amano Yasugawara, where the other gods met to figure out a way to lure the sun goddess out of seclusion. "Visitors pile stones into small cairns all around the cave entrance." Quoted from: Japan, by Robert Strauss, Chris Taylor and Tony Wheeler, Lonely Planet Publications, Inc., 1991, p. 669.

The photo to the left shows the torii entrance at the shrine. This was taken by and placed in the public domain by Fg2 at http://commons.wikimedia.org/. The dark image of the cave entrance with the multiple stone cairns was taken by Takasunrise0921 released to the public at the same wikimedia site.

NOTE: If you are asking yourself "What the heck does this have to do with Japanese prints?", well, I'll tell you. Over the years we have sold a number of prints in which Amaterasu was portrayed prominently. That's what! |

|

Takachiho also had another mythic claim-to-fame: Amaterasu's grandson, Ninigi-no-mikoto, was said to have descended to earth from heaven to rule over this realm. He landed on Mt. Takachiho. However, in Basil Hall Chamberlain's translation of The Kojiki: Records of Ancient Matters (published by Charles E. Tuttle, 1993, footnote 5, p. 136) "It is uncertain whether the mountain here named is the modern Takachiho-yama or Kirishima-yama, but the latter view is generally preferred. Kuzifuru [another name for Takachiho] is explained (perhaps somewhat hazardously) as meaning 'wondrous,' while Taka-chi-ho signifies 'high-thousand-rice-ears.' " Later Chamberlain tells us "So His Augustness-Prince-Great-Rice-ears-Lord_ears [another name for Ninigi-no-mikoto] dwelt in the palace of Takachiho for five hundred and eighty years. His august mausoleum is likewise on the west of Mount Takachiho." (Ibid., p. 156)

In Donald L. Philippi's translation of the Kojiki Ninigi-no-mikoto is called Piko-po-nö-ninigi-nö-mikötö and Takachiho is Taka-ti-po. Amaterasu, his grandmother, bestows upon him the myriad beads, the mirror used to lure her from her seclusion in the cave and the sacred sword. She said: "This mirror - have [it with you] as my spirit and worship it just as you would worship in my very presence." (Kojiki, University of Tokyo Press, 1995, pp. 139-140)

The X on the blank map of Kyushu shows the approximate location of Takachiho which is just 8 km down the road from "the cave".

TWO NOTES: 1) Understanding and explaining the variations in ancient Japanese names is way above my pay grade! Sorry. And, 2) Kojiki is 古事記. |

||

|

|

||

|

Amanojaku |

天邪鬼

あまのじゃく |

The devil figure beneath a temple guardian; a perverse person. In the glossary section of The Yanagita Kunio Guide to the Japanese Folk Tale, edited and translated by Fanny Hagin Mayer, amanojaku is said to be "A demon with feminie attributes." Matsumae Takeshi in "The Origin and Growth of the Worship of Amaterasu" argues that before there was the myth of the sun goddess there were a number of other myths popular among the people. In one of them the a giant, Amanojaku, played a good role. At that time there were seven suns in the sky which all appeared together creating great heat. So, Amanojaku, using a bow and arrows shot down all but one of these. In The Yanagita Kunio Guide to the Japanese Folk Tale (Indiana University Press, 1989, pp. 5-6) there is the legend of Urikohime (瓜子姫) or the Melon Maid. In this version an old woman finds a melon floating down a river. When she and her husband open it a beautiful little girl appears. As she grows larger she weaves every day. After a number of years the old couple decide to their 'daughter' to the village shrine festival. They go into town to buy a sedan chair to carry Urikohime in. While away an amanojaku comes along and urges that the young weaver let her in which she does. Once inside the amanojaku overpowers the Melon Maid, leads her outside, strips her and ties her to a persimmon tree. When the elderly couple return they find what they think is their 'daughter' sitting in her usual place weaving away as always. "They put who they thought was Urikohime into the chair and set out for the shrine, but the real Urikohime cried out from behind the persimmon tree, 'Don't put Urikohime in the chair! Only give the amanojaku a ride.' Greatly surprised, the old man cut off the head of the amanojaku and threw it into the millet patch. The stalk of millet is red because of this."

The image to the left was posted at Flickr by Hideyuki Kamon. |

|

Ame |

雨

あめ

|

Rain

Carlos F., one of our friendly contributors, suggested that we add a section on rain. He sent us the image shown above. It is from a Yoshitoshi print. Below is a detail of the frogs in the rain by Kuniyoshi to the left. The full print shows little frogs just above the signature. In time we will add commentary about rain in general and how it was viewed within traditional Japanese culture. This is just our preliminary entry.

I want to thank Carlos for making this suggestion and others which will be added to this site later.

All of the standard dictionaries translate amagaeru (雨蛙) as tree frog. However, Mock Joya refers to it as a rain frog and that translation is certainly commonsensical. "There are many kinds of frogs in the country. There are grotesque toads, to which are attributed evil spirits. Ao-gaeru, or green frogs are also called ama-gaeru or rain frogs, and it is said that their singing will bring rain." I have no way of knowing if the rain and the green frogs in this picture are an example of this belief, but they may be. Quoted from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 147.

|

|

|

雨に濡れ燕

|

The motif of swallows flying in the rain, most often associated with the kabuki character Nagoya Sanza.

|

|

Amerindian(s) |

アメリカ原住民

|

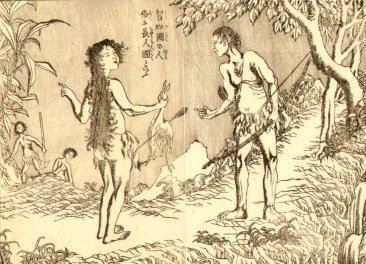

According to the Oxford English Dictionary the term Amerind was not coined until circa 1900 many years after the creation of the images seen to the left. When Sadahide (貞秀: 1807-1873 or 79?) drew his vision of native born Americans it probably didn't matter to him what they were called. Clearly he was working from a foreign model.

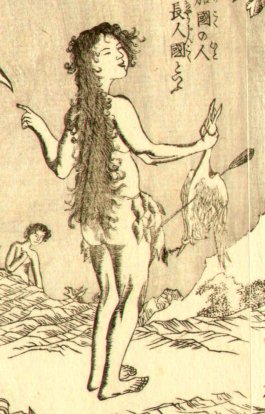

Fanciful concepts of foreigners were nothing new to the Japanese. Europeans were originally referred to as namban (南蛮 or なんばん) which literally translates as 'southern barbarians.' Even after the forced opening of Japan representations of foreigners were often rather exotic. For example, the image at the bottom shows a hirsute, newborn baby boy in his bath. At that time many Japanese believed that a child born of a Japanese mother and a foreign father would come out of the womb looking and acting like this. (Medieval Europeans believed that when Jesus was born he could walk, talk and read and why not?)

Before you are too quick to think the Japanese overly ignorant and superstitious drag out your copy of Herodotus. In Book IV of his "History" he describes a race of people who are born totally bald, flat nosed and with extremely long chins and who grow up that way. This was true of both sexes. But Herodotus was not completely gullible when he stated that "...these bald-headed men say (though I do not believe it) that the mountains are inhabited by men with goats' feet; and that after one has passed beyond these, others are found who sleep through six months of the year." Even this stretched his credulity.

Our great correspondent E. sent us the Sadahide images. E. said: "Leafing through some oddments the other day, I found this double-page bookplate by Sadahide and thought of you! From an 1855 book Meriken shinshi ' News from America' it purports to show how they perceived the native Americans. I don't really think that it will add anything to your index/glossary but I thought you might be amused."

Well, I was obviously more than amused and even though E. is right it doesn't add a lot to these pages I just felt it was too good to pass up. Thanks E!

As if having sex with a foreigner weren't bad enough for the Japanese clearly the off-spring would be profoundly affected. This is clear from the fully bearded baby shown above born of a Japanese woman and a Western man. In World Within Walls, by Donald Keene by Donald Keene the author quotes a senryū on this very topic: "In Maruyama/ Once in a while babies are born/ Without any heels." This sounds odd to us today, but no so much to the Japanese of the 18th century. The Dutch traders in Nagasaki wore shoes with heels. The locals thought this was because they didn't have heels of their own. |

|

Ameya |

飴屋 あめや |

Candy maker or candy shop

1892 oil painting by the

American Robert Blum (1857-1903) - ca. 1892 |

|

Ami |

網

あみ |

Ami-mon (網紋) or fishnet crest: According to John W. Dower there are very few water-based motifs used as crests even though Japan is comprised of a group of islands surrounded by huge expanses of water. Beside the fishnet the wave motif is another. Other than these very little is known about this form. Dower speculates that the ami was used as a crest because the implication of a big haul of fish meant good luck.

Source: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 119.

This motif is also related to our entry on hoshi-ami on our Hoshi thru Hotaru index/glossary page.

A shard from an Arita kiln bowl or cup from ca. 1620-80 showing an overall fishnet pattern. |

|

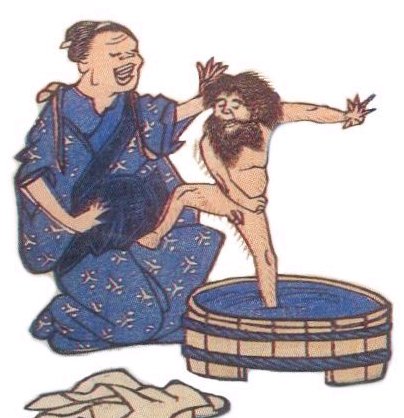

Andon |

行灯 (or 行燈)

あんどん |

Lantern: "...an ancient type of night lamp, consisting of a square or round frame of wood covered with strong rice papaer, the top and obttom being open. It is lit with rapeseed oil and a rush-weed wick on an oil plate inside. It is not used today except as a decoration."

Quote from: Dictionary Japanese Culture, by Setsuko Kojima and Gene A. Crane, Heian International, Inc., 1991, p. 9.

Tōrō (灯籠) is the generic term for lantern. Andons are only one type. "Smaller standing lanterns, usually made of iron, are known as andon. Andon became poular during the Edo period (1600-1868) for interior illumination, especially within the home. They usually rest on four legs and have cut-out designs decorating their sides... ¶Andon come in many different shapes and sizes and serve a decorative as well as utilitarian function. Some andon are made of paper with a rigid wooden frame and open top. These usually contained lamps burning rapeseed oil or candles; the modern version is often wired for electricity. One of their most attractive features is the oil plate (aburazara [油皿]) designed to catch the dripping oil; these are often decorated with beautiful pictorial designs and are highly valued today."

Quote from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 4, p. 368, entry by Nakasato Toshikatsu.

See also our entry on chōchin to contrast the difference between the andon and the hanging lantern.

In an 1880 section of "The Quarterly Review" it is stated that if a bachelor lights his pipe off an andon instead of an hibachi he will remain a bachelor. |

|

Ankō |

鮟鱇

あんこう |

A fish which is referred to by several names: Anglerfish, monkfish, frogfish, et al. An ugly bottom-feeder which was eaten in pre-modern times "...by the common people, especially in Edo (now Tokyo)..." to welcome the arrival of winter. (Kodanasha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 1, 1983, p. 56.)

Add goosefish as an alternative name just in case you want to look this creature up on Google or wherever.

This fish served as an element/prop in certain early, i.e., late 18th c. kabuki plays where they are seen being carried by a string. They are still used in modern cooking. One web site had a great photo of Julia Child preparing one of those ugly suckers.

After looking for several years we finally found a photo we could use. This has been done through the aegis of http://commons.wikimedia.org/. This was posted by Alexander Mayrhofer who gave permission for its use elsewhere. In this case the monkfish (Lophius piscatorius) was photographed in Bergen, Norway and while I am sure it differs slightly from those found in the waters off Japan the comparison is close enough. We are grateful for Mr. Mayrhofers permission to reproduce this image here. |

|

There are at least four representations of ankō in 18th century prints. Although I have seen a gazillion woodblock prints over the years those are the only ones I can remember presenting those ugly, ugly fish. In the first case from 1766 Bunchō shows an actor carrying two of them by a cord. Why he is carrying them is inexplicable. For some strange reason these fish came to be stand-ins for the the bell at the Mukenzan Kannon Temple. The bell when struck brought worldly wealth, but it also brought eternal damnation and suffering. In 1786 Shunkō created an image with three actors and one of them "...inexplicably, carries two frogfish (ankō) suspended from a piece of string." Below are details of these fish from both prints. The one on the left is the Bunchō.

Of course, researching further led to new information about ankō. There is a book entitled Sustainable Sushi: A Guide to Saving the Oceans One Bite at a Time by Casson Trenor (2009) which introduced me to the term ankimo (あんきも), the liver of the ankō, which seems to be a bit of a delicacy, an endangered delicacy. "Monkfish liver is similar to a fine pâté in texture and is often smoked or steamed..." "Monkfish was once considered a trash fish - no doubt partially due to its frightening appearance - and has only recently become acceptable to the American palate." As a sales ploy it is often passd off as scallops, scampi or even the "poor man's lobster." The author warns against over fishing because the ankō lives on the sea floor and has to be "...harvested using bottom trawls..." and suggests you pass on ordering it if you want it to be available in the future. The image on the left below is by トリュフ (Toryufu) while the one on the right is by Anyarei. Both were posted at http://commons.wikimedia.org.

In Chado: The Japanese Way of Tea, by Soshitsu Sen, Weatherhill/Tankosha, 1979, p. 617 is a nice description of various ways to eat ankō - preferably in December. "For suppon-ni, slices are cooked with sake and kelp in cold water, seasoned appropriately and served with chopped and washed Welsh onion, and ginger. For nimono it is garnished with wheat-glutin bread like chôji (light texture)-fu or shônai (thick, dried, baked)-fu. Since ankô is too soft to be cut on a board, it is hung up and cut; this is called tsurushi-giri. A pot of ankô and vegetables cooked in front of guests is not elegant but is quite tasty, especially the so-called seven tools of ankô are savoury: the innards such as the liver, gills, tail fin, ovary, stomach, cheek flesh and skin." The authors quote a saying: "Ankô has seven props making it worth its price."