Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

Si thru Tengai |

|

|

The molecular model on Lonsdaleite is being used as a marker for new additions from January 1 to May 31, 2021. The piece of sulphur posted at Wikimedia by Rob Lavinsky was used from June 1 thru December 31, 2020.

The detail from the diadem of

the Empress Eugénie |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Siddhartha, Siebold, Sino-Japanese War, Soba noodles, Sogimen, Soku mie, Sōmen, Sometsuke, Sōmoku-jōbutsu, Sōrei, Soroban, Sōsaku hanga, Sōtei-ō, Sugawara no Michizane, Sugi, Sugita Genpaku, Sugoroku, Suiba, Suiboku,

Suidobashi,

Suidobashi,

Suji-guma, Sung Dynasty,

Suridai, Surimono, Surishi, Suzu, Suzuki Harunobu,

Suzume, Suzume-bachi,

Takagi Umanosuke, Takanoha, Takao, Takarabune,Takaramono, Takara zukushi, Take, Takenoko, Takeuma, Taki, Takuan, Takuhon, Tamagiku-dōrō, Tamagushi, Tamaya, Tan, Tanabata, Tanawa, T'ang dynasty,

Tango, Tanuki,

Tatewaku, Tateyama, Tatsu no kuchi, Tayū, Tebori, Teihatsu, Tempō Reforms, Ten and Tengai

日清戦争, 蕎麦, 殺ぎ面, 束見栄, 染付, 草木成仏, 葬礼, 算盤, 創作版画, 宋帝王, 菅原道真, 杉, 杉田玄白, 双六, 水馬,

水墨, 水道橋,

雀蜂, 太刀,

鷹の羽, 高尾, 宝船,

寳物, 寳づくし, 竹, 筍, 竹馬, 瀧, 拓版, 玉菊灯籠, 沢庵, 玉串, 玉屋, 丹, 棚機, 手縄, 唐, 端午, 狸, 襷, 畳, 立涌, 立山, 龍の口, 太夫, 手彫り, 剃髪, 天保の改革, 点 and 天蓋 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|||

|

Siddhartha |

シッダールタ |

A 1922 novel by Hermann Hesse based on the life of the first historical Buddha. He is also referred to as Shakyamuni (釈迦). 1 |

|||

|

Siebold, Philipp Franz Balthasar von |

フィリップ・フランツ・フォン・シーボルト

|

German born physician (1796-1866) who went to Japan in 1822 as an employee of the Dutch government. Assigned to the small Dutch settlement on Dejima in Nagasaki harbor. Because his work gave him a lot of free time he was free to explore his many other interests. In 1824 he started a boarding school and soon was teaching Western medicine and treating Japanese patients. He was generally paid with ethnographic materials and art works. This became the core of his personal collection which in time was acquired by the Dutch nation and can now be found in the Sieboldhuis in Leiden.

The image of von Siebold on the postage stamp was posted on the Internet at http://commons.wikimedia.org by Le Corbeau. The image of the Siebloldhuis was also posted at that site.

Siebold took Hokusai prints back with him to Euirope in 1828. They may have met in person in 1826 when Hokusai would have been 66 years old. Siebold exhibited some of his ukiyo prints in the 1830s including the works of Hokusai, Kuniyoshi and Hiroshige.

"An interesting and unique coincidence which may be noted in this respect, is that Hokusai, although he was surely unaware of it himself, made his historical début in a European museum presentation at a time when he was still alive. The Dutch lithographers as Henri Ph. Heidemans, L. Nader and J. Erxleben, who produced the illustrations for Nippon from the Hokusai woodcuts, were among the first of nineteenth century Western design artists to be closely confronted with Japanese woodcuts. ¶ Thus, the availability of Von Siebold's publications during the first half of the nineteenth century and the existence of Von Siebold's Japanese Museum in Leiden, may well have played a role of considerable importance during the formative period of Japonaiserie in Europe and its consequent influence on European art." Quoted from: Leiden Oriental Connections 1850-1940, essay by Willem van Gulik, vol. 5, p. 388.

The illustrations in Siebold's volume Nippon were said to have been inspired by Hokusai's manga.

"Siebold's ukiyo-e collection is still regarded as among the finest in the world." Quoted from: The Rise of Landscape Painting in France: Corot to Monet |

|||

|

Japanese scholars who were interested in Western learning gravitated to him and soon he was handing out 'doctorate' degrees. In 1826 he accompanied a delegation to Edo to honor the shōgun. There he made friends with the court's astronomer who was particularly keen to learn more about Dutch culture and science. Their exchanges were beneficial for both of them. However, in time, the astronomer's enemies used this relationship against him and he was denounced as a traitor while Siebold was accused of being a spy for Russia. A purge of Siebold's Japanese friends and acquaintances took place and many of them were arrested. He was interrogated at length and finally in December 1829 he was expelled from Japan forcing him to leave behind a young mistress with their two year old daughter. ¶ Upon his return to Holland he set about organizing his collection. In 1831 the King made him advisor on Japanese affairs to the Ministry of Colonies. Eleven years later he was knighted. In 1856 his became the first professor of Japanese at the university in Leiden. In 1859 he returned to Japan as an employee of the Netherlands Trading Company. He wanted to be the Dutch government's representative in Japan, but his diplomatic skills were wanting he was refused that position. ¶ "His collection of Japanese ethnographic material was bought by the Dutch government in 1837 and became the foundation of the present National Museum of Ethnology (Leyden). He introduced to the Netherlands more than a thousand trees and plants, including ichō (Ginko bilboa), sakura (Prunus serrulata), hydrangeas, varieties of chrysanthemums, lilies and irises, and several kinds of coniferous trees. His botanical and zoological collections are preserved at the Botanical Garden, the National Herbarium, and the National Museum of Natural History, all at Leyden." (Quoted from: Frits Vos entry in the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 7, p. 193)

"Recent investigation, however, has turned up an abundance of other indications of Japanese material in France quite early on — for example, by 1843 the Cabinet des Estampes of the Bibliothèque Royale in Paris had volume six six of Hokusai's Manga, and many Parisian libraries owned several works by Baron von Siebold. They became even more numerous after 1853, when the American Commodore Perry finally forced the Japanese to open their ports. It is precisely in that year that 125 copies of the Catalogue liborum et manuscriptorum japonicorum a Ph. Fr. de Siebold collectorum annexa enumeratione illorum, qui in museo regio Hagano servantur were printed by the author in Leiden. In it, item 531 is the Book of Insects by Utamaro in its 1799 edition; and beginning with item 547, eleven works in twenty-three volumes by Hokusai, including one edition in ten volumes of the Manga, are listed. But this material remained remote from French artists. It was not until 1861 that the French — including the Jacquemarts and the Goncourts — began to visit the Siebold Collection. On 14 September 1861, on a trip through Holland, the Goncourts stopped in Leiden, were attracted by an Indian god, Ganesha, and reported that at the Musée Siebold 'the ink sketches of the Japanese artists . . . have the spirit and the picturesque touch of a sepia by Fragonard.' " Quoted from: The Documented Image: Visions in Art History, essay by Geneviève Lacambre, pp. 71-72.

The Siebold Incident: In 1826 Siebold visited Takahashi Kageyasu (高橋景保: 1785-1829) in Edo. "...the two traded books about Europe for geographic materials that included one or more maps of Japan recently prepared by the bakufu cartographer Inō Tadataka. ¶ By bakufu regulations, as Takahashi knew, such 'classified material' was strictly forbidden to foreigners, but in 1828 leaders in Edo discovered that Siebold had acquired some and that Takahashi their own official, had provided it. The discovery was cruelly fortuitous: Siebold, readying to sail for home, had stowed his possessions, but bad weather beached the ship in Nagasaki Bay. When his goods were unloaded to permit repair of the vessel, they were routinely inspected as incoming freight, and the contraband was discovered. The authorities promptly arrested him and held him in Nagasaki for a year, much as they had earlier held and interrogated Golovnin at Matsumae. They arrested Takahashi and nearly forty other scholars and translators in Edo and Nagasaki, sealed off and searched Dejima for incriminating material, and closed the translation center (bansho wage goyō) at Edo while investigating what they evidently regarded as a major spy case." ¶ When the Japanese realized that Siebold was German born and not Dutch they began to worry that he might be a spy for the Russians. Others were frightened by all foreigners and thought that all of them should be expelled and prohibited from coming to Japan in the future. ¶ Takahashi died while the investigation was on-going. One female diarist said that after his death his body was presrved in salt so the interrogation could continue. Takahashi was convicted posthumously and beheaded for his crime. His two sons were exiled. Source and quotes from: Early Modern Japan by Conrad Totman, pp. 510-11.

Marius Jansen points out the irony of the tragic ending of Takahashi Kageyasu because he was the one "...who proposed the famous 1825 edict ordering that foreign ships be repulsed on sight (muninen uchiharai rei). Quoted from: Rangaku and Westernization by Marius Jansen in Modern Asian Studies, 18, 4 (1984), p. 549. [Note: We believe that muninen uchiharai rei is 無二念打払令]

The interlude of relaxation during which Siebold was in Nagasaki found him lecturing to 56 students. During that stay Siebold, like many Meiji foreign teachers, had his students write essays in Dutch about Japan as the basis for his own publications. Thirty-nine of these survive. He himself drew up testimonial 'diplomas' for his students certifying to their proficiency in the subjects of his instruction. At the time of the crackdown occasioned by the discovery that he had been given a map, 23 of his students were taken into custody." Ibid., p. 551

In a 1971 issue of 'The Journal of Asian Studies' Kei Hirano Howes wrote: ""The most famous of the early medical pioneers to Japan is P. F. B. Siebald. Arriving in Japan in 1823, he made it his home for over six years, took a Japanese wife and fathered the first Western-trained Japanese woman doctor."

Hugo Munsterberg in The Japanese Print: A Historical Guide (pp. 4-5) notes that von Siebold had collected about 2,000 Japanese woodblock prints which he donated to the National Museum of Ethnology in Leiden. It is now one of the finest collections of its kind anywhere. "Since he often bought two copies of the same print, one for display and the other to be placed in storage, some of the prints from his collection are in mint condition, with the colors as fresh and vivid as they were when they were produced in the late Tokugawa period." They are strongest in the works of Toyokuni I, Kunisada, Eizan and Eisen, but also include prints by Utamaro, Hokusai and Hiroshige. |

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

Sino-Japanese War |

日清戦争 にっしんせんそう |

War between Japan and China 1894-5. 1 |

|||

|

Soba noodles |

蕎麦

そば |

Soba is the Japanese word for buckwheat, Fagopyrum esculentum. According to Foods & Nutrition Encyclopedia: A to H by Audrey Ensminger (CRC Press, 1994, p. 280) this plant is native to Asia and was being cultivated by the Chinese by the 10th century. Shu Suehiro says that it was introduced into Japan via Korea in the 8th century.

Robb Satterwhite in his What's What in Japanese Restaurants: A Guide to Ordering, Eating, and Enjoying (Kodansha International, 1996, p. 71) gives a good contrast between soba noodles and Western spaghetti: "Very different in character from Western-style spaghetti, soba has a richer aroma and taste and a firmer, less porous texture, so it's not as dependent on sauces to give it flavor."

Both images shown in this section were contributed to http://commons.wikimedia.org/ by Chris 73. The one to the left is of zaru soba while the one above is self- explanatory. We are grateful that both were placed in the public domain.

Locals were making soba noodles by the 16th century and within a hundred years they had become a popular dish in the restaurants and stands near temple and shrine entries.

|

|||

|

Menrui (麺類) is one of the generic Japanese terms for noodles. In The Japanese Kitchen by Hiroko Shimbo (Harvard Common Press, 2000, p. 155) the author tells us that the cultivation of soba "...is mentioned in the early Japanese history book Shokunihongi, written in 797. By the eighth century, the imperial government recommended growing buckwheat along with other grains..." Soba noodles were originally called sobakiri. By the Edo period the numerous noodles stands had become the 'fast food' of the period. ¶ Later the author adds: "Although buckwheat is grown throughout Japan, the cooler the climate, the more fragrant and rich-tasting the buckwheat."

"Traditionally, noodles were called nagamono [長物], which translates as 'things that are long,' and were eaten on hare no hi [晴れの日] (special days)..."

Quoted from: The Folk Art of Japanese Country Cooking: A Traditional Diet for Today's World, by Gaku Homma, North Atlantic Books, 1990, p. 165.

"Soba noodles are a regional food. Although buckwheat is grown throughout Japan, the cooler the climate, the more fragrant and rich-tasting the buckwheat. Hence the custom of eating buckwheat noodles has been much more prevalent in cool regions such as northern Japan (Tohoku), the Tokyo region (Kanto), and the central mountainous region (Shinshu). When you walk the streets of the cities and towns in these regions, you will spot soba noodle restaurants on nearly every street corner. Many of these usually modest-quality restaurants have plastic samples encased in glass outside of the building. There you can see soba noodles with tempura (tempura soba), soba noodles with duck and naganegi long onion (kamo nanban soba), soba noodles with mountain vegetables (sansai soba), soba noodles " with sweet, simmered fried thin tofu (kitsune soba), and many other soba dishes." Because it is a high-quality protein meal and it is full of vitamins and mineral rich it is considered a health food in Japan. (Ibid., p. 156)

For more information click on the yellow number one to the right. 1 |

|||||

|

Sogimen |

殺ぎ面

そぎめん |

Professor Leiter refers to this trick as humorous, despite its gory, bloody nature. " 'Sliced off mask,' a trick mask worn in humorous [choreographed fight scenes.] When the actor wearing it is sliced at by an opponent's sword, a clasp at the top of the mask is loosened. The front part of the mask falls forward, revealing a comically stylized representation of the inside of the actor's head." |

|||

|

Soku mie |

束見栄

そくみえ

|

Those familiar with ballet know that in the first position the dancer stands with the feet touching at the heels. The same is true here. Soku means 'sheaf' and I would suppose that the position of the actor in some ways mimics our vision of that object. There are quite a few different types of poses - "...a nonrealistic, sculpturesque, dance-like pose taken by one of more actors at a climactic moment in a play to make a powerful impression."

Quote from: New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of kabuki jiten, compiled by Samuel L. Leiter, 1997, pp. 403-5.

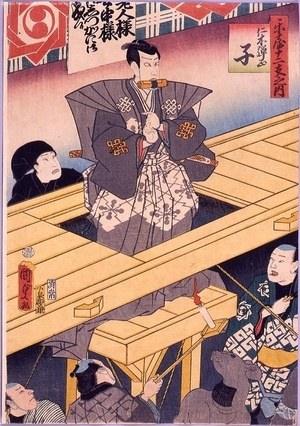

The image to the left above is a detail from a print by Kuniyasu where an actor is assuming the soku mie pose. The lower example is from a Toyokuni III vertical diptych. Click on the number 1 in the column to the right to see the full diptych.

Leiter in his The Art of Kabuki: Five Famous Plays (published by Dover in 1999, p. 257) refers to soku as "standing like a sheaf". |

|||

|

Sōmen |

そおめん |

An armored face mask. As yet we have been unable to find the kanji for this item and am not absolutely sure of the kana, either. This will be corrected when or if we find the correct characters.

"Full face masks (sô men) were not very highly thought of, for, while providing protection, they restricted breathing and vision; thus they were hardly ever used." (Quoted from: Samurai 1550-1600 by Anthony Bryant, p. 28)

To the left is our doctored image of part of the armor of Sanada Yukimura (真田幸村: 1570-1615). It was posted at commons.wikimedia by Raisa H.

"In order to protect his face, the bushi of the upper ranks usually wore a mask of iron, steel, or lacquered leather which covered the entire face from forehead to chin, or at least particular portions of it. Warriors of the lower rank and foot soldiers generally wore masks... [that] could be made from a single, rigid piece of metal or leather, or from several plates hinged together to make them more flexible." (Quoted from: Secrets of the Samurai: The Martial Arts of Feudal Japan by Oscar Ratti and Adele Westbrook, p. 217)

See also our entry on mempō. |

|||

|

Sometsuke |

染付

そめつけ |

Blue and white porcelain with a cobalt oxide underglaze.

In Modern Japanese Ceramics: Pathways of Innovation & Tradition by Anneliese and Wulf Crueger and Saeko Ito it says on p. 295 "Underglaze painting in cobalt blue on stoneware and porcelain (blue-and-white ware). Before application, gosu is mixed with concentrated green tea, the tannic acid in which prevents the pigment from bleeding when the glaze is applied."

To the left is a doctored photo of a 17th century Arita ware dish with underglaze blue and white decoration. It was posted at Flickr by Jondresner.

See also our entry on gosu. |

|||

|

Sōmoku-jōbutsu |

草木成仏 そうもくじょうぶつ |

The attainment of buddhahood by plants. This concept is mentioned in a number of Nō (能) plays, but according to Mark Cody Poulton is more of a theatrical device than the heart of the matter. Poulton's brilliant essay, "The Language of Flowers in the Nō Theatre", was a revelation to me on many levels.

Years and years and years ago I had the good fortune of studying for 7 years with the world's greatest expert on Chinese art and culture. One day I asked him about the nature of bodhisattvas, basically Buddhist saints, and he told me that these were figures which were capable of becoming buddhas, but chose not to until every last blade of grass had attained enlightenment. I have mentioned this to a number of people over the years and to a person anyone who thought they knew something about Buddhism argued with me. Sōmoku-jōbutsu it would seem would prove them wrong and my mentor right. |

|||

|

Dr. Poulton notes that this concept of attaining of buddhahood for plants has a number of contradictions built into it. According to some Buddhist tenets only sentient beings can attain a higher status and plants are not sentient. Added to this is the fact that the observed world is all illusion (maya) and plants are part of that category. Yet there are quite a few Japanese Nō plays where the main character is a tree or a flower which takes human form and speaks and moves about rather freely. In the play Saigyō-zakura (西行桜) the reclusive Heian poet Saigyō scolds - in verse - his cherry tree, which is particularly beautiful, for drawing visitors to it. "Ah, lovely blossoms, this is all your fault!" Unperturbed, the spirit of the tree - a male figure - steps out of a hollow in the tree to point out to Saigyō that his beauty is not his fault and that the poet needs to direct his displeasure elsewhere. The tree's argument wins the day. ¶ While these flower/plant-buddhahood-attainment plays are infused with Buddhist jargon and concepts, Poulton argues convincingly that most of this is just window dressing to underlying Shintō (神道) concepts. Of course, that makes sense because within Shintoism all things sentient and insentient can be possessed by spirits.

Poulton tell us: "As many as forty plays refer to the idea of sōmoku jōbutsu, or the buddhahood of plants. The phrase is part of a longer verse, When one Buddha attains the Way and contemplates the realm of the Law, The grasses and trees and land will all become Buddha. (ichibutsu jōdō kangen hōkai sōmoku kokudo shikkai jōbutsu)"

Among the tree and flower based Nō plays are the cherry tree (Sumizome-zakura 墨染桜), pine (Matsu 松), husband and wife pine (Takasago 高砂市), plum and pine (Oimatsu, literally 'the old pine' 老松), banana tree (Bashō 芭蕉), the red leaves of autumn (Tatsuta, a place to view these leaves, 龍田), iris (Kakitsubata 杜若), plum (Ume 梅), golden lace or Patrinia scabiosifolia (Ominaeshi 女郎花), wisteria (Fuji 藤), willow (Yūgyō yanagi 遊行柳), et al.

One cautionary note: Royall Tyler in his "Buddhism in Noh" does make the point that not only is Shintō an element of Nō, but so is Buddhism in the forms of Amidism and Zen. As far as which might be more important at any given moment Tyler quotes a passage from one play that say: "Gods and Buddhas only differ as do water and waves." |

|||||

|

Sōrei |

葬礼 そうれい |

Funeral - sōgi (葬儀) is a funeral service. "As I have stressed throughout this essay, funerals and memorial services are the mainstay of the Zen tradition in Japan and its most important contribution to Japanese Buddhism at large... What is most striking [is that the service for a lay figure] ...is that it is based entirely on the funeral of a Buddhist monk as it was practiced in Song and Yuan China. [¶] As soon as a Zen priest hears that one of his parishioners (danka [壇家]) has died, he goes to the home of the deceased and performs a sutra chanting at the time of death (rinjū fugin [ 臨終諷経 - literally: chanting of deathbed sutras]), commonly known as 'pillow sutras' (makuragyō [枕経]). [The section below continues from the same source.] |

|||

|

"On the night before the funeral (sōgi), there is an all night vigil (tsuya [通夜]) at which relatives and friends console each other and reminisce about the deceased. The priest performs an all-night vigil sutra chanting (tsuya fugin). [¶] On the day of the funeral the deceased is given tonsure (teihatsu [剃髪]), just as he/she were alive, and undergoing ordination as a monk or nun." The shaving of hair and beard are highly ritualistic. "The priest then sprinkles water in three directions, in front of the mortuary table (ihai) and to its right and left." More ritual recitations and acts take place prior to the cremation. The Zen funeral ceremony is one of the most elaborate and expensive to be found in Japan. (Source and quotes: Zen Ritual: Studies of Zen Buddhist Theory in Practice, edited by Steven Heine and Dale S. Wright, p. 71 ff) |

|||||

|

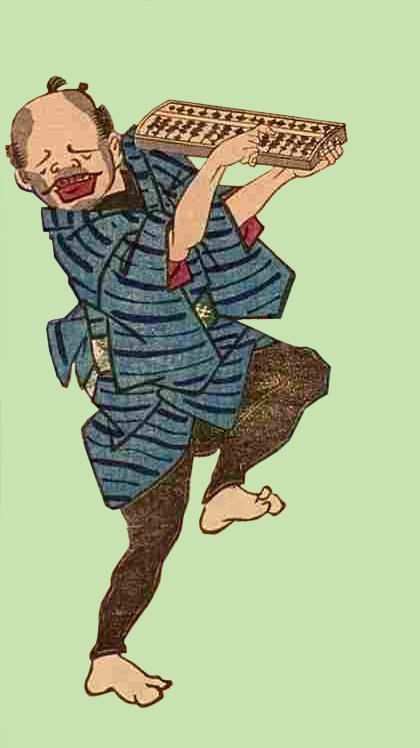

Soroban |

算盤

そろばん |

Abacus: A publication of a French mathematical congress held in 1902 stated that the soroban replaced the use of bamboo rods at the end of the 16th century. According to Sal Restivo in Mathematics in Society and History: Sociological Inquiries (pp. 55-56) Chinese mathematics was in decline as Japanese interests were developing. "The scholar Mori Shigeyoshi [毛利重能?: early to mid 17th century] who flourished in this period is Japan's first 'mathematician'. He is, according to legend, supposed to have traveled to China and returned with a knowledge of Chinese mathematical achievements and the suan-pan, a Chinese abacus. There is no historical basis for this story. The suan-pan was probably introduced to Japan much earlier. In any case, Mori was apparently a skilled manipulator of the suan-pan, known as the soroban in Japan . He taught the soroban arithmetic to many pupils, and may have written a text on the soroban, now lost." Two of Shigeyoshi's students wrote extant works which discussed the use of the soroban. Both wrote about square and cube root calculations and one of them also works on areas and volumes.

The soroban is referred to indirectly in the Chushingura.

To the left is a giga or comic print of a fellow happily using his soroban. It dates from ca. 1868. The image below was posted by 663highland at commons.wikimedia.org.

The samurai class looked dimly at subjects like mathematics because that was a tool of tradesmen, a lower class. In 1913 Frank Lombard wrote about Pre-Meiji Education in Japan: A Study of Japanese Education Previous to the Restoration of 1868. On page 106 he says: "Arithmetic was not encouraged in the terakoya [寺子屋: Buddhist temple elementary schools] and least of all in the government schools, attended by the higher classes. The occupation of trade was unworthy a samurai and only the introduction of Western science and the touch of Western commerce made Japan realize its value [i.e., the sarabon]. Even as late as 1835... the father of Yukichi Fukuzawa [福沢諭吉: 1834-1901], famed as the patron of Western practical learning, had a private tutor for his children who was preremptorily [sic] dismissed because he taught the multiplication tables."

Ten years earlier, in 1903, Sidney Gulick quoted Dr. George Knox: "A maid servant in China was made ill with astonishment when she saw her mistress, soroban (abacus) in hand, arguing prices and values. So was it once with the samurai." |

|||

|

The two characters which make up the word soroban are 算 calculate and 盤 board.

In Japanese Etiquette & Ethics In Business by Boye Lafayette De Mente notes on page 183 the saying soroban to awanai: "Literally, 'it doesn't agree with the abacus,' this is an old term used to mean that the price is too high or that a business proposition would not be profitable. It is still used fairly often in informal, casual situations."

In an argument for equal rights for women Fukuzawa Yukichi mentioned above said that since the world was basically divided equally into men and women it would be wrong for a man to take several wives. In translation it quotes him as saying: "...it does not conform to the computations on the soroban." (Quoted from: Sources of Japanese Tradition: 1600 - 2000, p. 46)

"Eiichi Shibusawa [渋沢 栄一] (1840-1931), a great contributor to modern Japanese capitalism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, believed the harmony between profit and righteousness is an immortal principle common to the Orient as well as to the Occident. He writes in his well known book Rongo to Soroban (The Analects and the Abacus)... 'the ethics of the samurai is the same as the ethics of business.' " (Quoted from: Encyclopedia of Business Ethics and Society edited by Robert W. Kolb, vol. 2, p. 210)

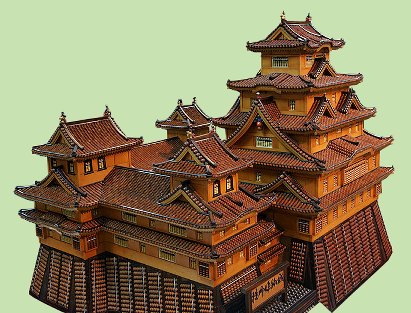

Above is a castle model made up of soroban. It is on display in the 'Ono City Tradition Industrial Hall' and was posted on the Internet at commons.wikimedia.org by 663highland.

The Japanese equivalent for 'reading, writing and arithmetic' is yomi, kaki, soroban.

"The simplest and perhaps the most senseless method of divination is by the abacus (soroban). Its use is confined to cases of illness. To the number of years of the patient has lived are added the numbers of the month and of the day of his birth. The sum thus obtained is multiplied by 3 and divided by 9. If the remainder is 3 or a smaller number, recovery is considered certain. If it is a number between 3 and 6, the case is grave, the danger growing as the remainder ascends. Equal division is counted as a remainder of 9, and signifies certain death." (Quoted from: Japan: Its History Arts And Literature, Vol. 5 by Frank Brinkley, p. 232)

There is a quote cited in Configurations of Culture Growth by Alfred Kroeber (p. 195) that the earliest printed image of a soroban-type abacus appears in a Chinese publication from 1593.

"About a million children in Japan still learn the abacus, at 20,000 after-school clubs... Inevitably, this is a drop from the 1970s, before the age of the electronic calculator, when, at its peak, 3.2 million pupils sat at the national soroban proficiency exam in a year. In fact, during the transition between the manual and electronic eras, a product combining both calculator and abacus was sold in Japan. Addition is usually faster on the abacus, since you get your answer as soon as you input the numbers. With multiplication the electronic calculator gives you a light speed advantage.... ¶ The abacus remains a defining aspect of growing up in Japan, a mainstream extracurricular activity like swimming, violin or judo. Abacus training, in fact, is run like a martial art." (Quoted from: Here's Looking at Euclid: A Surprising Excursion Through the Astonishing World of Math by Alex Bellos, pp. 40-41)

According to an article in the Japan Times from November 21, 2000 the small town of Yokota in Shimane Prefecture was the soroban making capital of Japan producing about 70% of the national demand. There were 21 abacus factories there in 1978 making 1, 200, 000 boards. By 1999 there were only 4 factories making a quarter of a million. There is a 'barnlike' museum there devoted to abacuses from Japan, China, Korea and Russia.

Prior to the introduction of the soroban the Japanese used counting rods or sangi (算木). In use as early as the 6th or 7th century they were cumbersome and hard to work with. When merchants adopted the soroban for business calculations sangi were still being used for higher math. In fact, sangi were still being used in the 19th century. |

|||||

|

Sōsaku hanga |

創作版画 そうさくはんが |

Creative print: a 20th c. invention where the artists does the drawing, carves the blocks and prints all by himself.

"Although the traditionally produced popular woodblock print must have seemed almost defunct by 1912, the vigorous seeds of a new sort of graphic art had already been sown by the artist, reformer and educator Yamamoto Kanae (1882-1946) who in 1904 made Japan's first creative print ('sōsaku hanga') designed, cut and printed by himself." (Quoted from: Japanese Art: Masterpieces in the British Museum, 1990, p. 233)

|

|||

|

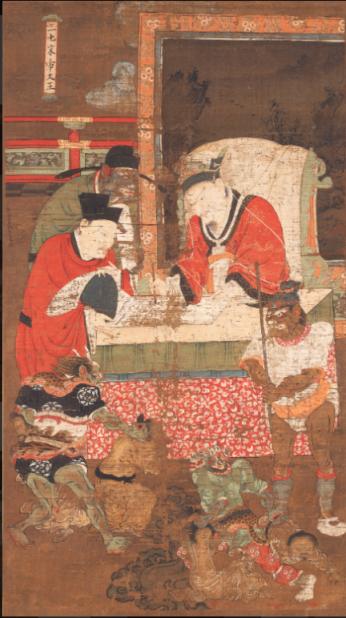

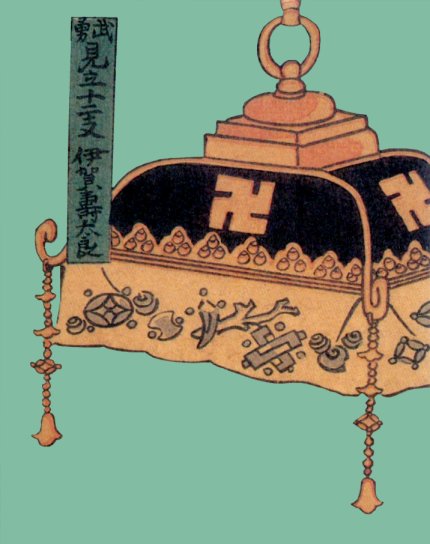

Sōtei-ō |

宋帝王

そうていおう |

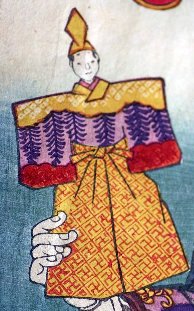

Third of the Ten Kings of Hell.

He presides "...at the entrance of the afterworld assigning souls to one or

another of the six realms of existence."

Literally his name, 宋帝王, could be translated as 'Song emperor.'

|

|||

|

Sugawara no Michizane |

菅原道真 すがわらのみちざね |

Michizane (845-903) was named as ambassador to China in 894, "...but his petition to the throne advocating the cessation of embassies to [that country] was granted and official relations between the two... lapsed for centuries." (Quote from Yamato Monogatari by Mildred Tahara, Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 27, no. 1, Spring 1972, p. 1)

This is our first entry begun on 2/13/10 on Michizane and we will be fleshing it out over the next few weeks to months or whenever. |

|||

|

Sugi |

杉

すぎ |

Cryptomeria motif: Dower notes that the "stately cryptomeria" was associated with numerous Shinto shrines from the earliest times. For that reason the wearing of this tree as a crest took on a religious significance. It also was considered an auspicious sign.

Source: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, pp. 54-5. 1

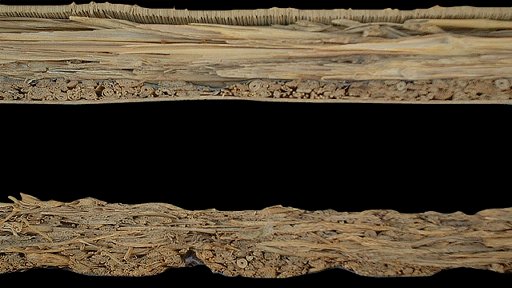

George Nakashima, a master woodworker, in his The Soul of a Tree... wrote: "Sugi, or Japanese cedar, or cryptomaria. Long straight, taut trunks. Very resistant to rot and decay. Temples and shrines, some comparable in scale to the European cathedrals, often had cryptomeria pillars which were dressed to perfect cylinders. Since the sugi grows in tight stands, each tree shares nourishment with its neighbors." |

|||

|

The Tokugawa shrine at Nikko is known for its Cryptomeria trees. In 1935 Catherine Blomberg wrote: "When the Meiji Shrine was built in Tokyo, individuals and groups of people donated young trees from all parts of of the Empire. In the same public-minded way of the Empire. In the same public-minded way Matsudaira, an ancient daimyo, having no money to give for the establishment of a memorial at Nikko for leyasu, founder of the Tokugawa Dynasty, contributed cryptomeria trees. It took the twenty years from 1628 to 1648 to plant them. The avenue, consisting of twenty thousand trees extending twenty-five miles in length, is now worth three million yen as timber wood but is considered invaluable as a national monument."

A number of sources say the sugi is the most spiritual of all Japanese trees. Thus its connection with the Shinto shrines and the kami.

In Carmen Blacker's The Catalpa Bow... she notes that the tengu "...is seen as a warden of forests, a guardian of huge trees. Mr Higashibaba, who was well over ninety when I met him in the summer of 1972, had lived all his life in a village on the slopes of Musashi Mitake. In the woods on this ancient holy hill, he informed me, there were still tengu to be seen when he was a boy. They appeared to haunt the great cryptomeria trees which in those days abounded on the mountain, and indeed appeared to be the guardians of these trees. One of the reasons why there were no more tengu in the woods was that the great trees had recently been ruthlessly felled. But eighty years ago he remembered some charcoal-burners telling him that they had been woken up from their midday nap by a tengu, who clearly resented their having cut down a large cryptomeria to make charcoal."

In 1971 Emperor Hirohito visited London and planted a Cryptomeria japonica at Kew Gardens. The next day the tree was found cut to the ground with poison poured over the roots so that it would never grow again. Next to it was a sign which read "They did not die in vain."

"In Japan, the sugi is a highly venerated tree. It is usually translated as Japanese cedar, but it is actually a false cypress (Cryptomeria japonica). The national tree of Japan, it is often found around Buddhist temples and Shinto shrines. An old tale, "Orosu", tells of the sacred sugi tree that whispers in the wind, and when the air is still asks the birds to deliver its messages. It is the king of the forest, and when it is harmed all the other trees assemble at night to heal its wounds." Quoted from: The Meaning of Trees: Botany, History, Healing, Lore by Fred Hageneder.

In the Nihongi, the second oldest written record of Japan, it says that the Cryptomeria were created from the plucked out beard and scattered hairs of a god. It is then mentioned that this tree and the camphor trees were the ones used to create 'floating riches', i.e., ships.

In Settings and Stray Paths: Writings on Landscapes and Gardens Marc Treib says that cedar moss or suigoke is called that because it looks like a forest of cryptomerias.

One of the oldest, if not the oldest, dugout canoe-like boat found in an archeological site in Japan was made from a Cryptomeria tree. Also, "The relatively short bows, of Jōmon times [10,000 to 350 B.C.] were made of strips of cryptomeria..." but the next generation of bows were made from yew. Source: Himiko and Japan's Elusive Chiefdom of Yamatai by J. Edward Kidder, Jr.

"Prevalent throughout Japan, it is found almost nowhere else in the world. The best-grade timbers come from Akita Prefecture in northern Honshu. Evenly grained, lightweight, and soft-textured, cryptomeria wood has a low oil content and a piquant aroma. It is easily split into wedges and sawed and shaved. Its ready availability nationwide makes it a primary structural timber for building. In furniture, it is used for everything from the smallest containers to large coffers (hitsu), trunks (nagamochi) , writing tables and desks (tsukue), and shelving (todana). Moreover, the fragrance of cryptomeria kegs imparts a distinctive sharpness to saké in much the same way that oak barrels lend body to whiskey. The sugi that flourish on Yaku Island off Kyushu (Yaku sugi) are prized for their exceptionally vivid grain pattern, which is highly regarded for its decorative value in architecture and furniture." Quoted from: Traditional Japanese Furniture by Kozuko Koizumi. |

|||||

|

Sugita Genpaku |

杉田玄白

すぎたげんぱく |

Genpaku (1733-1817) is one of the most important figures of 18th century Japan. He "....discovered that a Dutch human anatomy book provided names for body parts not found in Chinese medical texts. In 1771 he watched the dissection of a criminal's corpse, a fifty-year-old woman, performed by an outcast. Although this was not the first dissection performed in Japan, the evidence of his own eyes plus the Dutch text led him to invent Japanese terms for pancreas, nerve, and other body parts; these terms were later exported to China." Quoted from: East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History, p. 290.

After studying a Dutch translation of the German work of Johann Adam Kulmus Genpaku came out with a Japanese version, Kaitai shinsho. Other scholars aided him in the translation into Japanese.

Genpaku also gave an account of his experience viewing the execution of the female convict and her dissection in his Rangaku Kotohajime (蘭学事始). For more on rangaku, 'Dutch studies', go to our O thur Ri index/glossary page.

The image to the left is my doctored version of a photograph posted at commons.wikimedia.org by 663highland. |

|||

|

Here is an account from the Rangaku Kotohajime about a discussion Genpaku was having with Hiraga Genai (平賀源内:1729-79): " 'As we have learned, the Dutch method of scholarly investigation through field work and surveys is truly amazing. If we can directly understand books written by them, we will benefit greatly. However, it is pitiful that there has been no one who has set his mind on working in this field. Can we somehow blaze this trail? It is impossible to do it in Edo. Perhaps it is best if we ask translators in Nagasaki to make some translations. If one book can be completely translated, there will be an immeasurable benefit to the country.' Every time we spoke in this manner, we deplored the impossibility of implementing our desires. However, we did not vainly lament the matter for long. ¶ Somehow, miraculously I obtained a book on anatomy written in that country. It may well be that Dutch studies in this country began when I thought of comparing the illustrations in the book with real things. It was a strange and even miraculous happening that I was able to obtain that book in that particular spring of 1771. Then at the night of the third day of the third month, I received a letter from a man by the name of Tokuno Bambei, who was in the service of the then Town Commissioner, Magaribuchi Kai-no-kami. Tokuno stated in his letter that. 'A post-mortem examination of the body of a condemned criminal by a resident physician will be held tomorrow at Senjukotsukahara. You are welcome to witness it if you so desire.' At one time my colleague by the name of Kosugi Genteki had an occasion to witness a post-mortem dissection of a body when he studied under Dr. Yamawaki Tōyō of Kyoto. After seeing the dissection first-hand, Kosugi remarked that what was said by the people of old was false and simply could not be trusted. 'The people of old spoke of nine internal organs, and nowadays, people divide them into five viscera and six internal organs. That [perpetuates] inaccuracy,' Kosugi once said. Around that time (1759) Dr. Tōyō published a book entitled Zōshi (On Internal Organs). Having read that book, I had hoped that some day I could witness a dissection. When I also acquired a Dutch book on anatomy, I wanted above all to compare the two to find out which one accurately described the truth. I rejoiced at this unusually fortunate circumstance, and my mind could not entertain any other thought. However, a thought occurred to me that I should not monopolize this good fortune, and decided to share it with those of my colleagues who were diligent in the pursuit of their medicine." Quoted from: Japan: A Documentary History, vol. 1, pp. 264-5.

According to Marius Jansen Genpaku came to his interest in rangaku after reading "...Ogyū Sorai's discussion of military strategy...." Source: Rangaku and Westernization in Modern Asian Studies, 18, 4 (1984), p. 543.

"Sugita Gempaku's disciples numbered 104, and they were from thirty-eight provinces." Ibid., p. 551 |

|||||

|

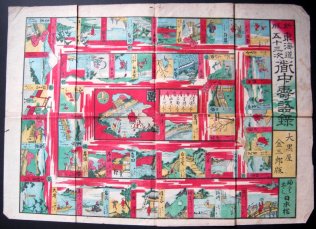

Sugoroku |

双六

すごろく |

A game played with dice on a large sheet of paper illustrated with a series of pictures. Like parcheesi a player moves according to the toss of the die. Traditionally it was played by children at New Year's. |

|||

|

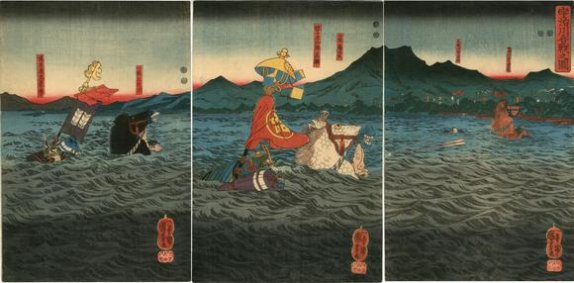

Suiba |

水馬 すいば |

Crossing water on a horse. This is also the name of an abumi or stirrup which is made like a colander to allow the water to flow through so that the foot will dry more quickly once the rider has exited the water.

The triptych to the left is by Kuniyoshi and is called The Battle of the Uji River (宇治川合戦之図). This example comes form the Lyon Collection. Click on the image to go to the page devoted to it. |

|||

|

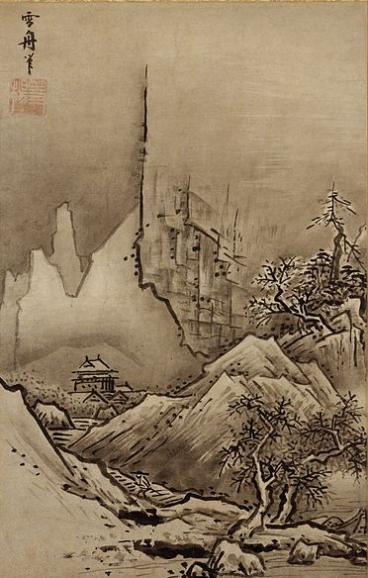

Suiboku |

水墨

すいぼく |

Ink painting: "Among Zen-inspired arts, the new vogue in painting was ink monochrome, which the Japanese call suiboku-ga --picture (ga) of water (sui) and ink (boku). Although light washes of color are often added, these paintings are generally executed in ink alone. Before Kano Masanobu (1434-1530), the early practitioners of suiboku-ga were all Zen monks. Some of them were able to travel to China where they learned the art firsthand from the Chinese. No doubt, artistically talented Ch'an refugees also helped the Japanese to learn this difficult medium of expression. Most Japanese painters, however, studied by copying valuable Chinese imports. By the late Kamakura period, the Hōjō regents had a sizable number of Chinese paintings. The collection was housed within the Enkakuji compound, in the Butsunichi-an, which was erected as the mortuary temple of Hōjō Tokimune. The first inventory of the collection, taken in 1320 and recorded in the Butsunichi-an Kōmotsu Mokuroku, includes a melange of objects that hardly qualifies as a standard of the collector's discrimination for Chinese paintings. Since most works were anonymous and were identified only by their subject matter, the names of only a handful of Chinese painters are mentioned. Mu-ch'i is an exception in this small group; his name appears three times. On the other hand, the fifteenth-century catalogue of the Ashikaga collection shows that the Japanese had reached a deeper understanding of connois- seurship in the time of the one hundred years after the Hōjō collection was formed. The Gyomotsu On-e Mokuroku, the catalogue of the Ashikaga collection of Sung and Yüan paintings, was purportedly edited by Nōami (1397- 1471), painter, connoisseur, and curator of the shogunal collection. Every painting in the catalogue is attributed; almost all painters are Southern Sung artists; and again, Mu-ch'i leads the list as the favorite, followed by Ma Yüan and Hsia Kuei. The romantic, idealized Southern Sung landscapes, which characteristically feature evocative voids and strong asymmetry in composition, became the basic models for Japanese paintings in ink monochrome." Quoted from: Japanese Art: Selections from the Mary and Jackson Burke Collection by Miyeko Murase, p. 87.

The image to the left is by Sesshu (雪舟: 1420-1506). |

|||

|

Suidōbashi |

水道橋

すいどうばし |

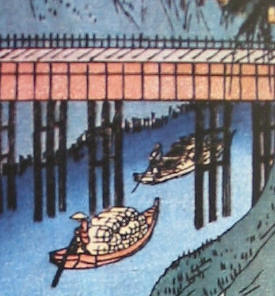

An aqueduct bridge over the Kanda river/canal in the Ochanomizu district. Today it is only a traffic bridge. 1 |

|||

|

|

水彩画 すいさいが |

Watercolor |

|||

|

Suisen |

水仙 すいせん |

Narcissus: Alfred Koehn says that in China this plant is referred to as the water fairy. Merrily Baird notes that the narcissus was native to neither China nor Japan, but may have been imported through the Arabs. "The Japanese force the flower into bloom in late winter and make it a symbol of the New Year... This New Year's association leads to the plant's status as an emblem of good fortune. So, too, does the fact that the second ideograph used to write the plant's name... means Taoist immortal."

The photograph shown above is from the wonderful site operated by Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/. |

|||

|

Koehn added: "In the Hua Shih 花史, History of Flowers, we read that the Narcissus was already highly prized in the eighth century when the Emperor Hsüan Tsung 玄宗 presented one of his concubines with red Narcissi, planted in gold and jade bowls. Yang Wan-li 楊萬里 [1127-1206]..." wrote:

They are wonderfully graceful

and fragrant too; |

|||||

|

Suji-guma |

筋隈

すじぐま |

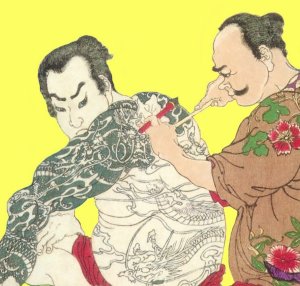

"Streaked" makeup: A special type of lined makeup meant to enhance actors performing in the aragoto or "rough stuff" style. It is meant to strengthen their masculine presence. Originated by Ichikawa Danjūrō (1689-1758) possibly influenced by earlier Chinese sources.

The detail to the left is from an 1894 print by Kunichika of Ichikawa Sadanji I as Umeōmaru.

|

|||

|

Sung dynasty |

宋朝 そうちょう |

Chinese dynasty noted for its cultural refinements 1 |

|||

|

|

鼈

すっぽん |

A slow-moving elevator trap used in kabuki theaters for the appearance and disappearance of actors. It was generally located on the hanamichi and was operated manually. Sometimes referred to as the 'snapping turtle.' |

|||

|

Suriawase |

磨り会わせ すりあわせ |

Integration, coordination, fitting together: Although this is a term applied to business and industry it is only mentioned once as far as we can tell when it comes to the production of woodblock prints. Shigeyoshi Mihara in Monumenta Nipponica (Vol. 6, No. 1/2, 1943, p. 260) refers to suriawase as "...a trial of newly cut blocks to assure that the colour blocks fit exactly in the allotted outlines on the key block." |

|||

|

Suribotoke |

摺り仏 すりぼとけ |

Ancient block prints of Buddhist images or invocations addressed to Buddha. These are among the earliest printed images in Japan created centuries before the first ukiyo-e - perhaps as early as the 9th to 10th century. These prints were frequently placed inside of Buddhist statuaries.

Suri (摺) means to rub or print on cloth. Hotoke (仏), here pronounced botoke, means Buddha. |

|||

|

Suridai |

すり台 |

Printing stand: Hiroshi Yoshida said in his Japanese Woodblock Printing (1939, p. 66) that "The suri-dai, or low stand for the blocks used for printing, should slope down about twelve degrees away from the artist."

Edward Strange wrote in Tools and Materials Illustrating the Japanese Method of Colour-printing: "The colour is then applied with a brush, to the upper surface of the block, which rests on a low stand (Suridai) to which are affixed four small cushions of wet cotton (Yawara) to prevent slipping... This stand should have a downward slope of about 2 inches in 1 foot." |

|||

|

Surimono |

刷り物 or 刷物

or

すりもの |

While literally listed as 'printed matter' surimono are much more than that. They were printed in small editions, often as gifts for members of poetry clubs. They stood outside of the restrictions put on commercially produced prints and they often were much more delicately carved and printed with much greater care than most other prints.

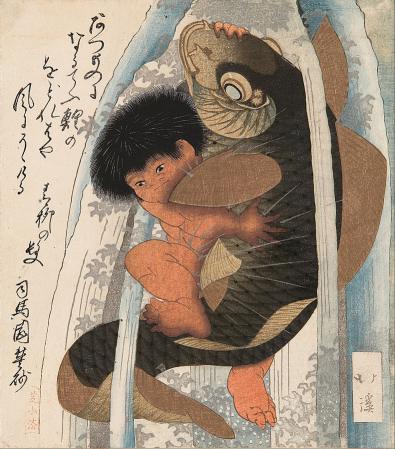

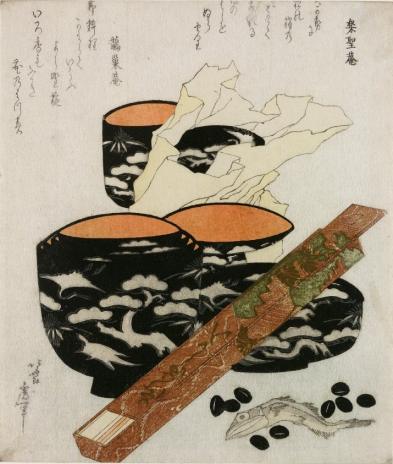

The Hokkei image to the left was posted at Wikimedia.commons. It is from the collection of the Art Gallery of South Australia. The one above was posted at the same place by Horst Graebner and is by Hokusai. |

|||

|

Von Seidlitz noted in A History of Japanese Colour-Prints (p. 14) that most commercial prints might require up to seven different color blocks "...but in the case of the surimonos... which were intended to be unusually sumptuous, especially at the beginning of the nineteenth century often [uses] twenty or even thirty [colors]."

Louis Gonse (1846-1921) referred to this art form in his L'art japonais from 1883 as "Les sourimonos sont, avec les lacques et les broderies, les plus séduisantes merveilles de l'art japonais, celles, entre toutes, qui étonnent le plus les indifférents."

Kurt Meissner noted: "The inserted poems were, to the donors and recipients, just as important it [sic] not more important than the illustrations. But few poems were written by renowned poets. The majority of them were by persons of entirely different professions even though they were interested and, to a certain degree, educated in "things literary." " Later he Meissner added: "It has already been said that the pictures and poems were often only loosely connected and sometimes seem to have no recognizable connection whatsoever. Moreover, the poems were often quite banal; at least they have that effect in translation. Those poems may have been meaningful among friends who could allude to some common experience; but today the charm of such allusions cannot be revived and only the pictures and not the poems can be fully appreciated." Quoted from: Japanese Woodblock Prints in Miniature: The Genre of Surimono.

"The standard-size surimono [i.e., smallish] was popular for those printed in Edo (Tokyo). The surimono printed in Osaka were huge in size as the number of club members who immortalized themselves with their poems on them was also very high. On the surimono of Edo, for example, two or occasionally four poems never disturbed the beautiful impression which the pictures made. Fifty or more poems, however, with the names of club member "poets" take up the greater part of the surimono of Osaka so that the picture is limited in size and thus of secondary importance." (Ibid.)

"About 150 years ago... the poems were just as important as the picture. The men who wrote the lines were not actually poets; most were laymen schooled in literary clubs—merchants, shop-owners, and the like, while the surimono pictures were by great artists. ¶ The poems—kyōka or sometimes haiku—were limited to 31 or 17 syllables. Today we do not know what feelings the giver and receiver had in common or what they had experienced together. Consequently, no matter how we try, we probably will never quite understand the full meaning and nuance that lie behind most of the poems. Besides, it is difficult to translate the lines into European languages so that the grace of the original poem can be felt." (Ibid.)

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

Surishi |

刷師 すりし |

The printer: "The carved blocks were then passed to a printer, or surishi 刷師, who inked the block, laid a sheet of paper on it, and rubbed the paper with a device known as a baren in order to make a good impression. In some cases... a proof was printed for correction before any further printing was undertaken, but this appears to have been a rarity." [This last point is in reference to book publishing and not print making.] Quoted from: The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth Century by Peter Kornicki, p. 48. |

|||

|

Suzu |

鈴 すず |

Bells - "Primarily associated with dances in Shinto shrines, the delicate suzu... in time came to be used by the Japanese both as a purely musical instrument and as an accessory which was sometimes worn on festive occasions, attached to items such as mirrors, bows and swords, or affixed to such animals as horses and falcons." Quoted from: The Elements of Japanese Design: A Handbook of Family Crests, Heraldry and Symbolism by John Dower, pp. 104-105.

Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The image to the left is a detail from a print in the Lyon Collection showing Tamizō II backstage in his dressing room. His casual robe with his crest is reflecting in his dressing mirror. Click on the detail to see the full print. |

|||

|

Suzuki Harunobu |

鈴木春信

すずきはるのぶ |

Harunobu (ca. 1725-1770), said to have created the first nishiki-e or multi-colored printed images. Woldemar von Seidlitz in A History of Japanese Colour-Prints published in English in 1910 said: "...after Harunobu in 1765 invented the colour-print proper with its unlimited number of blocks..."

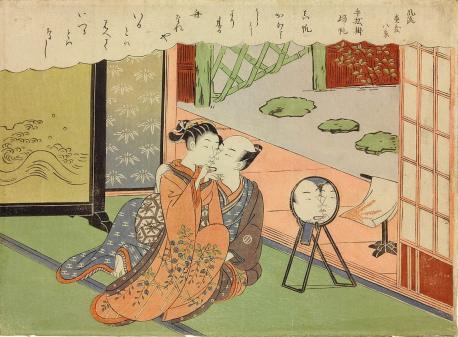

To the left is a Harunobu print from the collection of the British Museum. We found it at Wikimedia.commons. It is dated to ca. 1768. |

|||

|

Suzume |

雀

すずめ |

Sparrow - Passer montanus (Eurasian Tree Sparrow), named originally by Linnaeus in 1758.

"Transmigration from human soul into sparrow body is known. Mononobe no Moria, the principal antagonist of Prince Shōtoku in the fight of the old order against the new; of Shintō against Buddhism in the 6th and 7th centuries, was killed by an arrow, some say, an eye-glance, of Shōtoku. His soul thereupon changed into a sparrow. The bird flew about over the entire country, alighting only on Buddhist temple-roofs, which burst into flame immediately after the departure of the bird. The people calling this evil being: terasuzume, the sparrow of the Buddhist temples."

The photo to the left was posted at Flickr by Darren. The stamp shown above is a detail from a print by Hiroshige. |

|||

|

"Legend has it that the soul of Fujiwara no Sanekata, after he died of hunger in exile on the island of Ōshu, changed into a flight of sparrows, that frequently alighted in the imperial courtyard and were very annoying. The people called these birds 'nyū dai suzume, the sparrows that enter'." Quoted from: The Animal in Far Eastern Art: And Especially in the Art of the Japanese Netzsuke, with References to Chinese Origins, Traditions, Legends, and Art by T. Volker, p. 149.

There are several terms including the word 'suzume', which are indicators of Spring. |

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

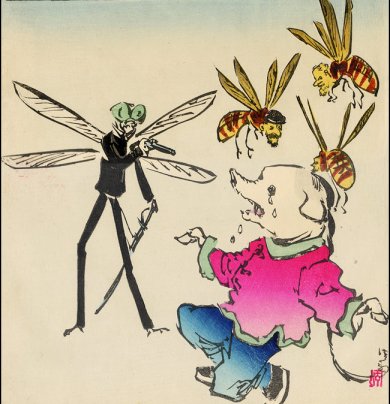

Suzume-bachi |

雀蜂

すずめばち |

Wasp or hornet 1

|

|||

|

|

足袋

たび

|

Japanese socks with a split toe: Mock Joya said "Tabi was originally of leather and worn outdoors only, and the indoor tabi appeared in the Tokugawa period." Jikatabi or rubber-soled tabi "...may be called the revival of the original tabi." Quoted from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 44.

"The Japanese custom of wearing tabi or socks indoors is comparatively modern. For many centuries the people were required to be barefooted when they wore formal attire. It was taboo by common etiquette to wear tabi in the presence of others. It is recorded that in the Imperial Court of the Muromachi period in the sixteenth century, tabi were absolutely prohibited. It was also forbidden in the Tokugawa Shogun's palace. Only those of extremely advanced age or those who were sick could wear tabi in the Imperial Court or in the Edo castle of the Tokugawa Shogun, with special permission. ¶ The history of tabi is very old. At first, used only for outdoor wear, they were made of leather. The shape was the same as the present tabi but made deeper to cover the ankle. They were always taken off as one entered the house. Gradually, however, they came to be used indoors too. Of course the indoor tabi were never used outdoors. Then, as the indoor tabi appeared, the outdoor tabi lost their popularity."

Courtesans never wore tabi even in the coldest weather or when out strolling in the snow. The appearance of their bare feet were considered arousing to men. The courtesans sometimes added white powder to their feet to heighten the effect. However, their young trainee/attendants, kamuro, did wear tabi.

The photograph to the left below shows two tabi in the collection of the Etnografiska museet in Sweden. The printed detail above that comes from a HIroshige surimono at the Brooklyn Museum. |

|||

|

Tachibana |

橘

たちばな |

A citrus fruit motif perhaps the mandarin orange: "Reputedly brought to Japan from China in the 3rd century A.D., the mandarin orange was immediately admired for its glossy green leaves, fragrant blossoms, and beautiful, succulent fruit." (Quote from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, pp. 62)

A National Geographic publication differs with Dower above and says the tachibana got to China in ca. 500.

Sometimes early on the tachibana was thought of as the fruit of immortality. Elsewhere this trait has been attributed to peaches.

The fragrance of the tachibana blossoms "...was believed to summon up remembrances of people one once knew..." according to Donald Jenkins.

Below is a detail from an Ellen Levy Finch photo posted at commons.wikimedia.

|

|||

|

W. G. Aston in his translation of the Nihongi (p. I:186) said that in the year 61 A.D. "The Emperor commanded Tajima Mori to go to the Eternal Land and get the fragrant fruit that grows out of season, now called the Tachibana." Nine years later the emperor died and a year after that Tajima Mori returned with "...the fragrant fruit which grows out of season..." He "...wept and lamented" and in the end he turned toward the emperor's tomb and died himself. [One source gives 田島間守 for Tajima Mori.]

Not sure about this, but the tachibana may be mentioned 66 times in the Man'yōshū (万葉集). (We will correct this number if we find it to be otherwise.) In one of these Yakamochi (家持: 718-85) is asked by his wife to write a poem in her voice to her mother. His style in this one is described as one of preciosity. He "...pretends to yearn for his mother-in-law because her voice is as sweet as orange blossoms in summer when the hototogisu sings..." (Source and quote from: Japanese Court Poetry by Robert Brower and Earl Miner, p. 108)

Norinaga noted: "On the whole, in the past people did not praise the fragrance of flowers. Although in the Man'yōshū we find many poems on the orange tree (tachibana), only two sing its fragrance..." (Quoted from: The Poetics of Motoori Norinaga: A Hermeneutical Journey by Michael Marra, p. 126)

Chapter 11 of The Tale of Genji is called Falling Flowers or Hanachirusato. "The poetic image of tachibana, (blossoming) orange tree or orange blossoms, plays an important role in this chapter. Starting from the falling flowers of the title... the image of orange blossoms, which evokes a rich cluster of poetic connotations, functions as a driving force in the tale, it creates a basis for the poems that are recited and alluded to in the text and permeates the whole atmosphere of the story. Orange blossoms as an image of poetry obviously possessed a strong power of suggestiveness, especially as it was expressed in a famous anonymous poem that goes back to literary sources of the eighth century and was included in an influential anthology of poetry compiled in the beginning of the tenth century: 'The perfume of orange blossoms awaiting the fifth month recalls the sleeves of someone long ago." (Quoted from: Literary History: Towards a Global Perspective, text by Gunilla Lindberg-Wada, vol. 1, p. 9) ¶ At the beginning of this chapter Royall Tyler translates a famous poem:

Many fond yearnings for an orange tree's sweet scent draw the cuckoo on to come seeking the village where such fragrant flowers fall.

Lindberg-Wada notes that the cuckoo is the male who is drawn to the tree, his female lover. She also notes that oranges were thought to "...alleviate the nausea of early pregnancy." (Ibid., p. 10)

"Orange blossoms are famous for evoking memories, but the fragrance of plum blossoms above all makes us return to the past and remember nostalgically long-ago events. Nor can we ignore the clean loveliness of the yamabuki or the uncertain beauty of wisteria, and so many other compelling sights." (Quoted from: Essays in Idleness: The Tsurezuregusa of Kenkō translated by Donald Keene, p. 19)

In the Shinkokinshu (新古今集: 1223) Shunzei (俊成: 1114-1204) wrote:

In a future age Will the fragrance of these orange blossoms Move someone again To think of me when in my turn I too shall be a person of the past?

'Shunzei's daughter' had written a similar poem which was also included in the Shinkokinshu - published in An Introduction to Japanese Court Poetry by Earl Miner with translations by Robert Brower, p. 119:

A moment's doze Within the circle of the scent Of the orange flowers - Even in dreams the fragrance stirs my heart To recall his scented sleeves of long ago.

In Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney's Kamikaze, Cherry Blossoms, and Nationalisms: The Militarization of Aesthetics in Japanese History (p. 53) she notes that: "For many Japanese, integral to the image of the imperial palace are a cherry tree on the left-hand (east) side and a citrus tree (tachibana) on the right-hand (west) side in front of the South Garden of the main building. The two symbolize the two divisions of the imperial guards. The image has become familiar even to children through the observation of the Doll's Festival on March 3, celebrated at the individual home in front of a replica of the imperial court with the emperor and empress, together with the paired plants of the cherry on the left and the citrus tree on the right..."

Liza Dalby in her East Wind Melts the Ice: A Memoir Through the Seasons (p. 237) says: "The tachibana tree is placed next to the emperor in the tiered display of Girls' Day Dolls, while a cherry tree sits at the side of the empress. On the right side, everlasting beauty; on the left, ephemeral beauty."

In an 1883 published translation of the Tsurezuregusa Kenkō passes a lonely hut and feels sorry for its occupant: "...I saw an orange tree, with branches bending under loads of fruits; and all around it a strong fence built to protect the fruit from theft. On seeing this my sympathy abated. How much better if that tree had not been there!" Donald Keene gives a different translation (p. 11) where the orange tree has been translated as a tangerine tree.

Some of the individuals and families that used the tachibana as their crest or mon: Ii Naomasa (井伊直政: 1561-1602); the Obayashi (大林); the Kuze (久世) at Sekiyado (関宿); the Udagawa (宇田川); the Matsudaira (松平) at Shimahara (島原?); the Yakushiji (藥師寺); the Matsumura (松村); the Maki (牧); the Kawanabe (川部); the Kuroda (黑田) at Akizuki (あきずき); the Odera (小寺); the Kimura (木村); the Maeda (前田); the Wada (和田); the Yonekura (米倉); the Ichino (市野); and the Monna (門 奈). (Source: Mon: The Japanese Family Crest by Kei Kaneda Chappelear and W. M. Hawley, p. 17)

One mon or crest used by Arashi Kichisaburō II was the tachibana. Normally this would not pose a problem. However, there was one example cited in A Kabuki Reader: History and Performance where it did. C. Andrew Gerstle in his chapter on Kabuki patrons wrote about this. Fans were thought to be disloyal if they supported one artist, but then visited the dressing room of another. Or there was the case of "Ikka from Imabashi [who] was suspected of duplicity when he produced a surimono... with a design of tachibana... that formed the crest of Arashi Kichisaburō II... Utaemon III's great rival.

The Ichimura group of actors adopted the tachibana as one of its crests. The two examples below come courtesy of the great Kabuki web site http://www.kabuki21.com/index.htm. The one on the right comes from a print showing Ichimura Uzaemon VIII

Sometimes the only way an actor can be identified for sure was by their crest which generally could be found fully displayed, partially displayed or barely displayed on their robes - or sometimes in another part of the print. Here, however, the mons are all shown on robes. The example on the left below is from a Bunchō print from ca. 1768-70. It appears on the robe of Ichimura Kichigorō. The one in the center appears on a Shunshō print on the robe of Ichimura Uzaemon IX from 1770. To the right the subtle tachibana crest - also by Shunshō - is on a different robe worn by the same actor but from 1777.

In 644 there was a millennial craze which predicted the coming of the tokoyo no kami (常世神) or God of the Everlasting World. "As one Ōfube no Ōshi urged his followers to prepare for the advent of the tokoyo no kami, large numbers of believers began worshipping a god that Ōfube described as a worm that could be found on the tachibana, or Japanese orange tree. Believing the tokoyo divinity would come and bestow riches and immortality upon the faithful, Ōfube's followers engaged in ecstatic singing and dancing as they disposed of all of their possessions upon the roadsides. The cult proved to be short-lived, however, as Hata no Kawakatsu... killed Ōfube as disorder spread." (Quoted from: Shotoku: Ethnicity, Ritual, and Violence in the Japanese Buddhist Tradition by Michael Como, p. 33)

Aston gives the account from the Nihongi. Here Ōfube no Ōshi is called Ohofu Be no Oho. "[Ōfube told his followers:] 'Those who worship this God will have long life and riches.' At length the wizards and witches, pretending an inspiration of the Gods, said: - 'Those who worship the God of the Everlasting World will, if poor, become rich, and, if old, will become young again.' So they more and more persuaded the people to cast out the valuables of their houses, and to set out by the roadside sake, vegetables, and the six domestic animals. [Aston defines this as the meat of the horse, ox, sheep, pig, dog and fowl.] They also made them cry out: - 'The new riches have come!' Both in the country and in the metropolis people took the insect of the Everlasting World and, placing it in a pure place, with song and dance invoked happiness. They threw away their treasures, but to no purpose whatever. The loss and waste was extreme." (Aston, II: pp. 188-9) The worm itself is described as "...over four inches in length, and about as thick as a thumb. It is of a grass-green colour with black spots, and in appearance entirely resembles wth silkworm."

No one has been able to identify precisely which worm it was that was found on the tachibana. However, as you read above it has been compared to the silkworm. Since the only green ones we could find were Vietnamese and photographed by GeorgesA those are the ones we chose to use. This image was posted at commons.wikimedia.

"It is now clear that the followers of Ōfube's tachibana worm cult drew upon a reservoir of symbols associated with immigrant deities from Silla [Korea] as well as weaving cults and goddesses originally rooted in Western China." (Como, p. 53)

There is a major Japanese clan called Tachibana. It uses the same kanji character as the fruit. According to Kei Kaneda Chappelear: "In the Nara period (708) Emperor Shōmu [聖武天皇: 701-56] decreed that the name Tachibana be reserved for the exclusive use by the Imperial descendants of Emperor Bitatsu [敏達天皇: 538-585]."

In Chado the Way of Tea: A Japanese Tea Master's Almanac by Sanmi Sasaki (p. 280) it says: "There is a reason to believe that tachibana is the origin of Japanese confections."

|

|||||

|

Tachibina |

立雛

たちびな |

Standing dolls are usually made of paper. There is the taller male figure and the shorter female. He wears a short-sleeved kimono or kosode with hakama (袴) 'pants' or formal divided skirt. She, a paper wrapped cylinder, also wears a kosode tied off with a paper obi. 1

"The standing hina [doll] forms are the most rudimentary of the group and are closest in structure to the earliest doll forms employed in the nascent Hina-matsuri [doll or girl's festival celebrated on the third day of the third month] from the sixteenth century. The oldest forms are barely differentiated by sex: a pair of figures each with long trousers made of paper painted with auspicious designs. Over time the paper was stiffened and textiles were applied, allowing the dolls to stand more readily on their own or to be propped up against the back of the display area. The most common Edo form has the male with his arms stretched wide, visibly displaying the long sleeves of his coat. The female in clear distinction is depicted as a simple cylinder with no discernible arms or legs. Neither figure is typically shown with hands or feet."

Quoted from: Japanese Dolls: The Fascinating World of Ningyo, by Alan Scott Pate, Tuttle Publishing, 2008, p. 59.

|

|||

|

|

蓼藍

たであい |

Tade (蓼) is knotweed and ai (藍) is indigo. Henry D. Smith II wrote in 'Hokusai and the Blue Revolution': "The other organic blue was natural indigo (tade-ai), which was widely used in both prints and paintings. The pigment was fairly costly, however, since it had to be extracted either from the surface froth of fermenting indigo or from cloth that had already been dyed with indigo, both laborious processes that yielded 'indigo sticks' (aibō, or, as in Tōho's account, airō, 'indigo candles', after the cylindrical form) for use by painters. Indigo also has a low tinting strength, so that relatively large amounts are needed to achieve good colour. It will fade over time with exposure to light, although it is much more stable than dayflower. Finally, the hue of the extracted indigo pigment tends to the greyish green, yielding fairly dull blues when printed."

Above are indigo cakes posted at Wikimedia Commons by David Stroe. The image to the left is of paper stained by indigo. It was posted at the same location by Palladian. |

|||

|

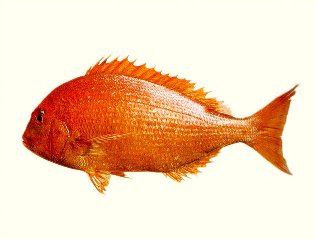

Tai |

鯛

たい |

The king of fish. Served on New Year's holidays and on other special occasions. For much more on tai click on the 1.

"One of the great classic oshi sushi dishes of Osaka is made with tai, or bream. Fillets of the fish are seasoned first with apricot juice, then wrapped in konbu kelp along with rice and pressed in a mold. This tai no oshi sushi, or shime-dai no oshi sushi, was reputedly a favorite of the imperial family back when they were calling the shots from Kyoto." Quoted from: The Connoisseur's Guide to Sushi: Everything You Need to Know About Sushi Varieties And Accompaniments, Etiquette And Dining Tips And More by Dave Lowry, pp. 41-2 |

|||

|

Below is a detail from a photo posted at Flickr by colincookman. It shows a giant tai being carried through the streets of Karatsu-shi, Shiga prefecture. There is a description of a anothere tai festival held in Toyohama. "Annually in Aichi Prefecture, a procession of young men winds through the city streets of Toyohama, behind a Mardi Gras-scarlet, bungalow-size tai (sea bream) made of paper and bamboo. The parade ends when the fish float, along with the men, drunk on sake and buck naked, go careening right off the dock and into the waters of the harbor. The ceremony has to do with ensuring a good catch for the season or propitiating local deities or something like that." Ibid, p. 248

There are a number of accounts that state that Tokugawa Ieyasu died after eating tai. One early account comes from William Adams, the first Englishman to have visited Japan. "The men were still wondering how to dispose of yet another supply of unwanted goods when they were interrupted by unexpected and unwelcome news from the court in Shizuoka. Ieyasu was ill, and no one knew if he would recover. ¶ His sickness had begun after one of his customary hawking tours. He had celebrated his return with a lavish banquet, dining on freshly caught sea bream cooked in sesame oil. But the meal had disagreed with him and he found himself seized with violent cramps. The pain was temporarily allayed by medicine, but it was not long before the cramps returned and he grew weak from the pain." Adams added that it was probably stomach cancer that did him in. Source and quote: Samurai William: The Englishman Who Opened Japan by Giles Milton, p. 251 |

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

Taikomochi |

幇間

たいこもち |

A professional jester; a buffoon; comedian or flatterer; sycophant; brown-noser - "...the taikomochi... used to ply his trade in the licensed quarters. The taikomochi was considered a male geisha. He called forth a repertory of zashiki gei (parlor arts)—amusing dances, jokes, songs, games, and impersonations—to assist visitors to the pleasure quarters in having fun. In return for his services, the taikomochi would receive goshūgi (tips). Professional taikomochi are practically extinct, but other kinds of professional entertainers (including hanashika) and extroverted amateurs assume some of their roles at parties today." Quoted from: Rakugo: Performing Comedy and Cultural Heritage in Contemporary Tokyoby Lorie Brau, p. 82.

"The word "humor" as both noun and verb defines the taikomochi's métier: he endeavored to keep the guests in a good mood. In the exaggerated comic characterizations of rakugo tales, a taikomochi is a sycophant, rubbing his hands together in anticipation of a tip. An anecdote often employed in prologues for stories about taikomochi relates how Ippachi (the typical name for taikomochi in rakugo) runs into one of his patrons on the street. The patron remarks, "Isn't it a lovely day?" Ippachi replies, "Yes, just gorgeous.” The patron then contradicts himself. “But there are a few clouds coming in.” Ippachi doesn't miss a beat. "Looks like there will be some rain later." As the conversation continues, Ippachi confirms whatever his patron says. In the end, one cannot trust what a taikomochi says because his sole motive is to please and be monetarily rewarded for being agreeable." Ibid.

The image to the left which has the word taikomochi in the title is by Kuniyoshi. It is from the collection of the Tokyo National Museum.

|

|||

|

Taisei Hōkan |

大政奉還 たいせいほうかん |

"The event called the Taisei Hōkan (大政奉還 returning the power to the emperor) brought an end to over seven hundred years of Japan's shogunate, and the national politics were handed over to the new reformist government." Quoted from: Seeking the Self: Individualism and Popular Culture in Japan by Ishikawa Satomi, p. 185 |

|||

|

Takagi Umanosuke in Bingo Province |

|

Subject of a print by Kuniyoshi from the series "Sixty Odd Provinces of Japan - Dramatic Chapters" 1 |

|||

|

Takanoha |

鷹の羽

たかのは |

Falcon (or hawk) feather motif: Considering the masculine nature of falconry and its appeal to the military class it is no surprise that this motif would be used as a family crest or mon. Merrily Baird in her Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design (p. 108) she notes that "...falcons and hawks became natural emblems of the Japanese warrior class due to their keen eyesight, their predatory nature, and their boldness."

In crest design feathers were understood to be substitutes for the full images of falcons.

|

|||

|

Takao |

高尾

たかお |

Tragic courtesan from the kabuki play "Date Kurabe Okuni Kabuki" or a similar play working with the same basic theme. Today it is only known as a minor subplot of a more important, but originally unrelated work. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 |

|||

|

Takarabune |

宝船

たからぶね |

Treasure ship which is said to sail into ports on New Year's carrying the Seven Propitious Gods and their jewels and other symbols of good luck.

The Japanese would place a picture of the takarabune under their pillow on the second night of New Year's. It was meant to bring pleasant dreams which would serve the dreamer for an entire year.

In Things Japanese by Basil Hall Chamberlain it says: "Pictures of this 'Treasure Ship' are hawked about the streets at New Year time, and every person who puts one into the little drawer of his wooden pillow on the night of the 2nd January, is supposed to ensure a lucky dream. At the side of the picture is printed a stanza of poetry so arranged that the syllables, when read backwards, give the same text as when read forwards." (1905 edition, p. 308)

"The first dream of the New Year, for example, is traditionally held to have special significance. Known as the hatsuyume [初夢], people would once try to influence its content by placing a picture of a ship bearing wealth and good fortune (called the takarabune) under the sleeper's pillow. In this way it was hoped to encourage images of plenty and the smiling influences of Ebisu and Daikoku." From: Ceremony and Symbolism in the Japanese Home, p. 78.

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Toyokuni I and shows only two of the seven gods. |

|||

|

Takaramono |

寳物 たからもの |

The "Myriad Treasures" often linked to the 7 Propitious Gods. 1

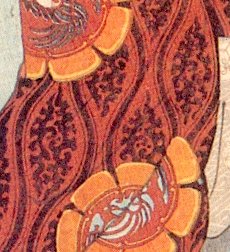

In a 1919 publication by the Victoria and Albert Museum A. D. Howell Smith gives a 'Guide to the Japanese Textiles'. He noted that "The takaramono, twenty in all, are a number of precious objects associated with Shichi-fuku-jin, or Seven Deities of Luck (Bishamon, Benzaiten, Daikoku, Hotei, Yebisu, Jurōjin and Fukkurokuju). They are sometimes depicted as borne in the Taka-ra-bune, or Treasure Ship; or else Hotei or Daikoku is seen carrying them in a bag. The takaramono consists of the following: - A merchant's weight (fundō), scholar's scrolls (makimono), rolls of brocade (orimono), and anchor (ikari), a 'cash' device enclosing a conventional four-petalled flower lozenge (shippō no uchi no hanabishi), coral (sangojū), the sacred keys (kagi) of the godown or storehouse of the Gods, cloves (chōji), the mallet (tsuji) of Daikoku, a thousand riō (a species of coin) in a box (koban ni hako or senriōbako), a copper coin (zeni) and a cowry shell (kai), the flaming jewel of the Buddhist Law (hōju no tama), sometimes replaced by lions chasing the jewel (shishidama) or by a stand supporting several jewels, the orange-like fruit (tachibana), a jar (kotsubo) containing coral, coins or precious goods, harpsichord bridges (kotoji), the flat Chinese fan (uchiwa, emblem of authority), the lucky rain-coat (kakuremino, a protection against demons), the hat of invisibility (kakuregasa), the inexhaustible purse (kanebukuro) and the hagoromo (feather robe of the tennin)." (pp. 39-40) |

|||

|

Takara zukushi |

寳づくし たからづくし |

Assorted lucky treasures |

|||

|

Take |

竹

たけ |

As the bamboo motif: The plant was imported into Japan from China and became a basic element in the gardens of the nobility. This association with the upper classes is not surprising considering its significance to the Chinese. In China there were only two - some say three - recognized arts. The greatest was calligraphy and the other was painting. Both were performed with basically the same materials. In painting the greatest form was the rendering of bamboo. Intrinsic to the plant were all kinds of positive traits: resilience in the face of adversity, i.e., wind or cold and suppleness or its ability to bend and adapt. There were judged to be among the most desirable qualities.