|

|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

|

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY De thru Gen |

|

|

|

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Deai chaya, Degatari zu, Dendendaiko, Dentōteki kōgeihin, Dōbori, Dohyō, Dōkko, Dokufu-mono, Dōsa, Dōsojin, Dotera, John W. Dower, E, Ebi, Ebisu, Ebiya, Eboshi, Edehon, Edo, Egawa Tomekichi, Egoyomi, Ehon, Ekikyō, E-kyōdai, The Elements of Japanese Design, Ema, Emakimono, Emma, Emonzaka, Empō, Engawa, Etoki bikuni, Enju , The Forty-seven Loyal Retainers

出会い茶屋, 出語り図, 伝統的工芸品, 胴彫, 土俵, 独鈷, 毒婦物, 礬水, 道祖神, 褞袍, 絵, 蛯, 恵比須 or 蛭子, 海老屋, 烏帽子, 絵手本, 江戸, 江川留吉, 絵暦, 絵本, 易経, 絵兄弟, 絵馬, 絵巻物, 閻魔, 衣紋坂, 延宝縁側, 槐, 絵解き比丘尼, 四十七士 |

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Deai chaya

|

出会い茶屋

であいちゃや

|

'Rendezvous teahouse' or love hotel: "Love hotels, or at least “adult hotels” exist in the United States as well, but they are often seedy low-rent joints in the wrong parts of town. By contrast, Japanese love hotels, often enveloped in blazing neon and gaudy architecture in the style of such landmarks as the Disneyland castle and the Statue of Liberty, are situated so that couples can quickly dart in off the street without attracting attention. In other areas, they are often set back from the highway to allow inconspicuous entrance through the rubber-curtained doors that close just in time to prevent passersby from glancing at one’s license plate. In either setting, for about $50 for two hours or $100 for the entire night, a couple gets a fully-furnished room, often furnished with rotating beds, mirrored ceilings, glass bathtubs, and entertainment extras such as large-screen televisions and karaoke machines. For a little extra, theme rooms are available, featuring everything from traditional Japanese furnishings to Cinderella fantasies to medieval torture chambers." Quoted from: Law in Everyday Japan: Sex, Sumo, Suicide, and Statutes by Mark D. West, 2010. p. 146.

Later West writes: "Once inside the hotel, customers choose a room. At smaller and older hotels, the decision may be made through a sort of “front desk” at which a clerk, usually shielded from the waist up to avoid exposing a customer’s identity, simply slides the customer the key to an available room. At most hotels, however, the system is more sophisticated. Upon entering, customers are faced with an array of photos of the hotel’s room accompanied by a description of the room’s amenities and the fee schedule. Available rooms are backlit. (If no room is available, as is often the case on weekends and holidays, many hotels have a clock that gives approximate waiting times, the determination of which is a science in and of itself.) To choose a room, a customer presses a button under the appropriate picture. The button triggers a trail of lights that direct the customer from the lobby to the appropriate room." (Ibid., p. 149) |

|

Degatari zu

|

出語り図

でがたりず

|

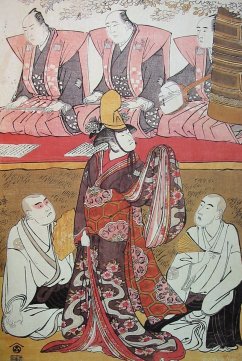

Prints which include images of the musicians who accompanied many kabuki performances. John Fiorillo provides a wonderful commentary about this genre. He notes that the literal translation of this term is "pictures of narrators' appearance".

The use of such musicians and chanters makes sense because of the early link between kabuki and music and dance. Long before kabuki had become what we know it as today these different art forms were all parts of a whole. In time they evolved to musicians and a narrator on raised platform behind the actors.

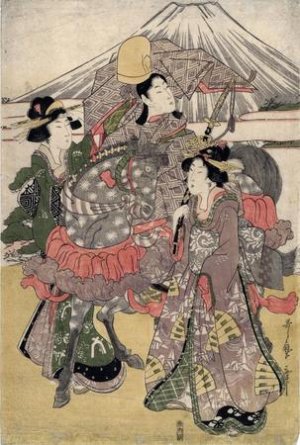

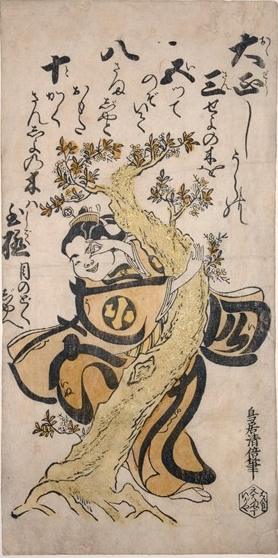

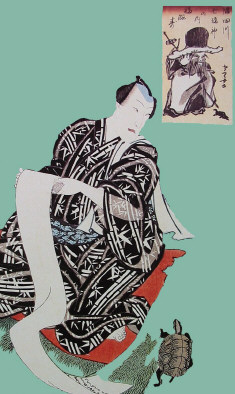

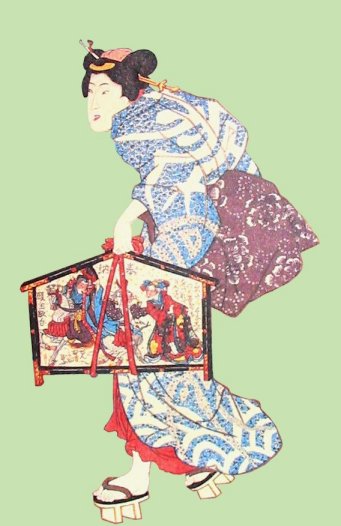

The image to the left above is by Toyokuni I (Ca. 1811-14) was sent to us by our great contributor Eikei (英渓). Thanks Eikei! The one below that is by Kiyonaga who created this style.

Michener in his The Floating World translates degatari as "come out with words".

"Kabuki borrowed from Noh and Bunraku in creative ways and modified the received stylistic conventions. When a play from Bunraku is being performed in Kabuki, for example, the gidayu chanter, accompanied by samisen players, is seated on a dais on the stage left apron. This form of narration is called degatari ('visible narration'). In some instances, the narrators and players are placed in an alcove set on stage left and screened from view by a bamboo blind." (Quoted from: Japanese Classical Theater in Films by Keiko McDonald) Gidayu is the narration for Bunraku or puppet theater. "This form of chanted narration, originated by Takemoto Gidayu (1651-1714), is extremely strenuous, and actors study it from an early age to develop their voices." (Quote from: Kabuki: A Pocket Guide) Samuel L. Leiter in his Historical Dictionary of Japanese Traditional Theatre says that "Gidayū initiates degatari convention of chanting in full view."

Kiyonaga (清長: 1752-1815) was the originator of the print sub-genre known as degatari zu or "pictures featuring the accompaniment". (Source: Ukiyo-e: An Introduction to Japanese Woodblock Prints by Tadashi Kobayashi) "It is a degatari-zu (a print depicting a dance scene with degatari... in the background), a genre made popular during the Tenmei era (1781-89) by Kiyonaga..." (Quoted from: Masterpieces of Japanese Prints: Ukiyo-e from the Victoria and Albert Museum by Rupert Faulkner) |

|

In My Friend Hitler and Other Plays of Yukio Mishima it states that another term for degatari is yuka no jōruri. The yuka is a slightly raised platform at stage left and angled toward the audience.

In Brandon and Leiter's volumes on Kabuki degatari is translated as "onstage narrative". They also note that the performers wear formal costumes.

"The general term for the musicians and singers who appear on the stage is degatari, a word written with two Chinese characters meaning to come out and to declaim." (Quoted from: The Kabuki Theatre by Earle Ernst)

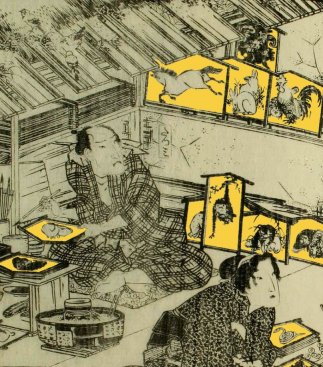

"In the Kabuki, the players of the various schools of music are always seated on the stage in full view of the audience. There is a great deal of formality in their arrangement, quite unlike the happy-go-lucky placing of Chinese theatre musicians, who also sit on the stage. The various schools by long tradition occupy special positions during the performance. Nagauta players sit at the rear of the stage facing the audience. Kiyomoto and tokiwazu players sit at the left of the stage to the audience and gidayu players to the right.... ¶ All stage musicians, of whatever school, wear kamishimo, the ceremonial dress of the samurai in former days." This costume appears to date back to the time when Takemoto Gidayu received an honorary title from the government. ¶ "There is a strict formality about the movement of the musicians of the stage, who sit motionless and upright when not performing. In the case of gidayu, both musicians bow on first appearing before the audience, and the tayu lifts the script from the small reading stand in front of him and places it to his forehead as a mark of respect. They sit on a dais, which is known as the degatari dai, it is built on a revolving base divided from the backstage by a screen, against which the musicians sit. In the middle of a play, the degatari dai can be swung round to reveal two more musicians on the other side and this way, the performers are relieved in the speediest fashion without interfering with the course of drama on the stage." (Source and quotes from: The Kabuki Theatre of Japan by Adolphe Clarence Scott) |

||

|

|

||

|

Dendendaiko |

でんでん太鼓

|

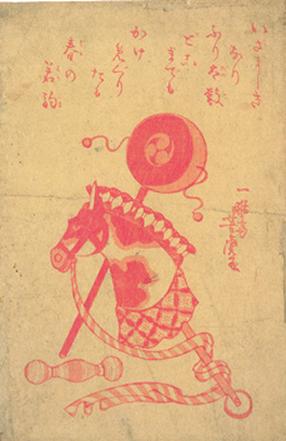

The print to the left is an aka-e or red picture which was often posted as a talisman in an attempt to ward off smallpox - especially from children. These are also know as hōsō-e.

"In Japan, the drum-on-a-stick (den-den taiko) with two thread and bead attachments has always been one of the cheapest and most popular toys for small children. It is shaken or twisted between the fingers and thumb so that the beads strike the stretched paper sides of the drum. Often decorated with lucky toys and auspicious symbols, its noise amuses children and was believed to ward off evil spirits." Quoted from: Playthings and Pastimes in Japanese Prints by Lea Baten, p. 99.

The image to the left is from the collection of the Naito Museum of Pharmaceutical Science and Industry. Another copy of this print appears in Japanese Popular Prints... by Rebecca Salter, p. 120.

On February 9, 2011 David Parfitt wrote to say that the drum in the print published by Rebecca Salter was a dendendaiko. Somehow that message slipped through the cracks and I failed to follow up until today, December 13, 2017. My sincere apologies to Mr. Parfitt and thank you for trying to bring this to my attention so many years ago. I hope this goes a little way toward correcting this mistake. |

|

Dentōteki kōgeihin |

伝統的工芸品 でんとうてきこうげいひん |

"The Ministry of Economy, Trade & Industry has designated precisely 206 crafts as authentic Japanese handicrafts - under a law that refers to them as Dento-teki Kogeihin... or 'Traditional Crafts'" This requires that 1) they must be items used in everyday life, 2) it must be handmade and beautiful in a traditional way, 3) it must be made in a traditional way, but modern techniques may be applied if it retains the traditional look, 4) it comes from a craft which has existed for at least 100 years and 5) there must be at least 10 workshops employing a minimum of 30 craftsmen. |

|

Dōbori |

胴彫 どうぼり |

Body carver: In the hierarchy of carver skills this ranks below that of 'head carvers' and 'hair carvers'.

"There were two categories of carvers, the kashirabori (literally carvers of the head) and dōbori (carvers of the body). The kashirabori were the most highly skilled and had overall responsibility for the blocks and would hand out work to the dōbori in line with their abilities. At every stage in its production the nishiki-e print was truly a team effort. In addition to nishiki-e carvers, there were also specialists in lettering." (Japanese Woodblock Printing by Rebecca Salter, p. 61)

Salter also notes that while d literally means 'body carver' in general it means any area of a woodblock not carved by the most skilled carvers. (Ibid., p. 126)

For more information see our entries on kashirabori and menbori. |

|

Dohyō |

土俵

どひょう |

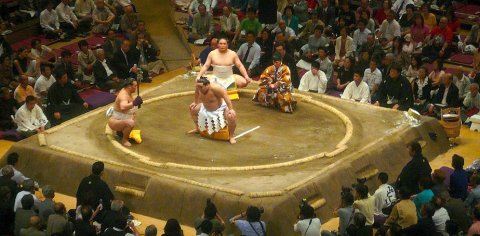

"...the round ring on which a sumō bout is held. The area is surrounded by partially buried slender straw bags filled with earth forming a circle 4.55 meters in diameter on a 5.45-meter-square mound of hardened clay. There is also a line of bags forming a square along the edge of the mound. At the center of the rings are two white parallel lines that serve as markers where the wrestlers place their fists during the shikiri. Above the ring hangs a Shinto-shrine-style roof, a legacy of the days when sumō was held outdoors with the roof supported by pillars at he four corners of the mound. When the sport turned professional and was moved indoors, the roof was preserved as a symbol of sacredness which the pillars were removed to give the spectators a better view." Quoted from Japanese-English Dictionary of Japanese Culture by Setsuiko Kojima and Gene A. Crane.

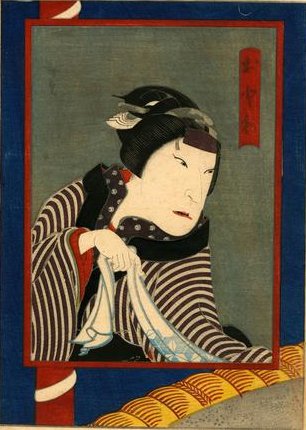

Below is a print from the Lyon Collection which prominently displays part of a dohyō as an element of the design. The kabuki figure represents Otowa (おとわ) from the play Sekitori Sen Ryō Nobori [関取千両幟] or 'Rise of the 1,000 Ryō Wrestler'. She is the wife of famous sumō wrestler who gets involved in a complicated intrigue. Otowa sells herself into prostitutions so she can raise the money to get her husband out the fix he has gotten himself into. Click on the image to go to the page devoted to this print in the Lyon Collection and read a fuller account.

|

|

Dōkko |

独鈷

どつこ |

A single-pointed vajra. There is a story that when a dōkko was thrown once it lodged in a pine tree. This became the future site of Kōyasan, the center of Shingon worship.

The image to the left shows the Danjyōgaran (壇上伽藍), one of the two most sacred sites at Kōyasan. Perhaps this is where the dōkko stuck in the tree. If not here, then somewhere nearby. This picture was posted at commons.wikimedia by Daderot. There is a similar story about a thrown sanko. See also our entry on kongōsho.

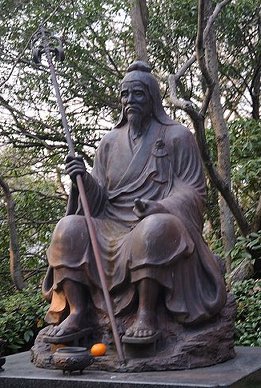

Philip Nicoloff describes a statue in the women's hall at Kōyasan of En no Gyōja (役行者), the ascetic who was said to be the founder of Shugendō. "He is sitting stiffly upright in a rocky cave. His face is gaunt. He wears a pointed beard. His body is thin to the point of emaciation. The right hand grips a ringed walking staff. The left hand holds a single pointed vajra or dōkko." The legend of his birth is that his mother swallowed a dōkko in a dream.

The image shown above of a healthy looking En no Gyōja was posted at commons.wikimedia by Reggaeman. |

|

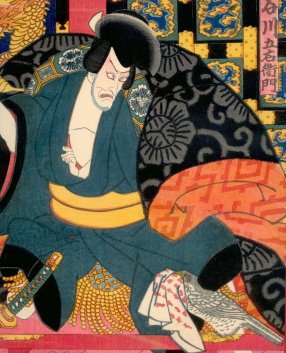

Dokufu-mono |

毒婦物

どくふもの |

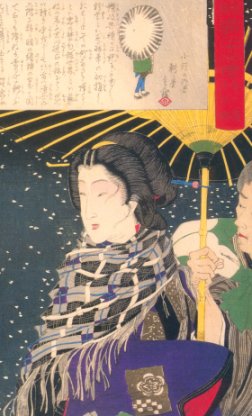

Evil woman genre - "Early Meiji crime writing was dominated by a form known as dokufu-mono, or “stories of poisonous women.” The dokufu-mono were criminal biographies that narrated the colorful exploits of female outlaws such as the notorious flimflammer and seductress Takahashi Oden, who was beheaded in 1879 after being convicted of using her feminine wiles to con and murder a used-kimono dealer. The Tale of Takahashi Oden the She-Devil (Takahashi Oden yasha monogatari, 1879) by Kanagaki Robun (1829–1894) is the most famous version of Takahashi Oden's life and the most famous example of the dokufu-mono genre. The genre's popularity ensured that the dokufu quickly became a well-known and predictable type: silver-tongued, alluring, cunning, defiant, usually oversexed, and quick to steal or kill or both. ¶ The earliest example of the genre is generally thought to be a three-day serial that appeared in 1876 in a newspaper started by Kanagaki Robun, the Kana-yomi shinbun (Phonetic Reading Newspaper). The story appeared under the title “Onna tōzoku Otsune no den” (The Story of Otsune the Female Thief)." Quoted from: Purloined Letters: Cultural Borrowing and Japanese Crime Literature, 1868-1937 by Mark Silver, p. 30.

The Kunichika image to the left is from the collection of Waseda University. It dates from 1879 and shows Onoe Kikugorō V as Takahashi Oden. |

|

Dōsa |

礬水

どうさ |

Sizing for paper

The image to the left was found at Pinterest via delrorosco.wordpress.com. It shows a picture of "Brushing dosa (a sizing liquid) onto the Kumohada paper." |

|

Hiroshi Yoshida wrote that it seemed to him that in time the sizing disappears from a woodblock print and that this has a positive effect. "I know for a fact that sizing does disappear in time for sized paper may be all right for use for a year or so, but after a longer time the paper has to be resized to be in a proper condition for printing, showing that the sizing does disappear. And I know also that when hōsho [奉書] paper-comes fresh from the paper-maker, the pleasing feeling which its surface gives is almost irresistible. Equally remarkable is that loss of that pleasing feeling, which one cannot help noticing, when paper comes back after having been sized prior to using it." ( Japanese Woodblock Printing by Hiroshi Yoshida, 1939, p. 7) ¶ Yoshida stresses the use of sizing for kyōgō or black ink keyblock prints used for making color blocks. "Black ink keyblock print used for making color blocks. "If a sheet of paper lacks dôsa, it will shrink when the pigment is put on to indicate the colour, and the colour block made from it will be smaller than it should be, and will not agree with the others. No emphasis can be too great to stress the fact that a kyôgo must be made right..." (p. 31) ¶ Dōsa "...gives the paper the right surface; it is absolutely necessary..." for the proper absorption of color during the printing process. (p. 41) "Moisture is necessary because of dôsa, and dôsa is necessary in order to harden the surface of the paper, both front and back. Otherwise it cannot be rubbed, as it must be in the printing, and the paper will stick to the block and be damaged." (Ibid.) ¶ Preparation: Sizing should be thicker in the summer than the winter. "Dôsa is prepared by boiling glue and alum in water in the following proportion: glue about thirty-three ounces and alum about fourteen ounces, boiled in about four gallons of water. This is the proportion for preparing the standard dôsa for the top side of the hôsho paper." (p. 74) The sizing is applied to the front of the sheet of paper by a broad brush and then hung up to dry. Then the procedure is repeated for the back side. Dôsa should be applied during dry days and not wet ones. ¶ "It is impossible to print on hôsho without dôsa. The paper sticks to the block, and the baren will not move smoothly on the back, but will damage the paper." (Ibid.)

In the Complete Printmaker: Techniques, Traditions, Innovations (by John Ross and Clare Romano, Simon and Schuster, 1991, pp. 39-40) another description is given for the preparation and application of dôsa. After heating one gallon of water an 8 ounce stick of animal glue is broken into pieces and dissolved in it. 3 to 4 ounces of alum are mixed in. Strain this through a double thickness of cheesecloth. Apply the sizing while still hot.

Sizing has a long tradition of use in European art going back to at least the 12th century. It too had an animal base and was probably produced in somewhat the same way. However, its use was somewhat different. In Japan or anywhere else for that matter sizing permits a far more controlled application of ink or pigment onto and into paper. Too much size and there will be no absorption. Too little and the ink/color will spread uncontrollably. ¶ In the West sizing served another purpose: It protected the support, i.e., canvas, panel, etc., from the corrosive effects of various binders or media.

"The size prevents the binder in the subsequent layers of the painting from being absorbed into the support, thereby weakening the painting. In addition the size prevents the penetration into the support of binders and vehicles that may have a deleterious effect on the support material. In the case of canvas, size also shrinks the fabric, to a taut smooth membrane (held, of course, by the stretcher)." A ground of gesso was placed on top of the layer of size. "Gesso - a mixture of animal glue, chalk (calcium carbonate), and at times a white pigment - has been used for centuries as a ground for both wooden panels and canvas." Today's gesso is not generally made with animal glue. Also, gesso serves another purpose dealing with the reflection of light from the paintings surface.

Source and quotes: The Science of Painting, by W. Stanley Taft, James W. Mayer, Richard Newman, Dusan Stulik, Peter Kuniholm, published by Springer, 2000, pp. 3-4.

And still more about European sizing: "The first stage was to give the whole panel, including any attached parts of the frame, several coats of glue size. Ordinary animal skin glues, boiled to a jelly and then dried in leaves for later reconstitution, were probably used, but according to Cennino the best size was made from parchment clippings soaked and boiled in water. These parchment clippings were waste product of the cutting of sheep or goat skins into rectangular sheets for manuscripts. The resulting glue is clear and pure, rather like modern cooking gelatine. The first applications of size were primarily to reduce the absorbency of the wood, preventing it from soaking up the adhesive from the later ground layers giving it as Cennino says 'a taste for receiving the coats of size and gesso' just as though 'you were fasting and had a handful of sweetmeats, and drank a glass of good wine, which is an inducement for you to eat your dinner'."

Quote from: Art in the Making: Italian Painting Before 1400, by David Bomford, Jill Dunkerton, Dillian Gordon and Ashok Roy, National Gallery, London, 1990, p. 17.

Question: Is there any connection between the Japanese use of sizing and that of the West? Was it a cultural borrowing? If anyone out there knows please contact me. Thanks.

Note that alum can in time produce sulphuric acid which can cause either the degradation of the paper or discoloration or both. Controlling the amount of alum used in sizing must be precise to avoid this problem. Surely Hiroshi Yoshida must be aware of this. In Japanese Papermaking: Traditions, Tools, and Techniques by Timothy Barrett (note #4, p. 285) the author notes "In the past most washi was not sized. When it was, animal glue with some alum was used as a surface size and applied with a brush to the dry sheet. Very early (pre-1400) sutra papers seem to show a surface size that was glazed or pounded into the paper after application of the size. Rice paste may have been added to the vat before sheet forming of some early Japanese papers to act as a size or to change the paper's texture." "Internal size" is a description of paper where the sizing was added to the vat during papermaking. "External size" or "surface size" is dôsa applied after an untreated sheet of paper has been made. "Surface sizes (such as starch or gelatine) not only alter resistance to liquids but also effect surface smoothness, erasability, strength, gloss, stiffness, and printability." (p. 305) |

||

|

|

||

|

Dōsojin |

道祖神

どうそじん |

"A type of deity; a guardian of roads and village boundaries, worshipped in the form of stone images along the roadside. Also known as sae no kami [塞の神 or さえのかみ]... an ancient designation that suggests the function of 'obstructing' or 'keeping out' (sae) evil spirits. The dōsojin is often identified with the god Sarudahiko, who guided... the supposed ancestor of the imperial line, on his descent to earth. The object of worship takes various physical forms: a pair of figurines; male and female; an inscribed stela; or a simple stone, round or phallic in shape." Today their function has been expanded to support marriages, births and especially children.

Quote from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 2, p. 132, entry by Ōtō Tokihiko.

In the The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender by Bernard Faure (published by Princeton University Press, 2003, pp. 233-4) notes that "...those stone statues of the bodhisattva Jizō, which originally marked the border between this world and the other." Later Faure follows this with information about the 'stone woman' (umazume [石女]) which refers to a sterile woman, but also has allusions "...to a certain type of lithic marker, the so-called uba-ishi [乳母石], meaning in this case, stones that are endowed with the power to bring fertility. One apparent exception is the 'Killing Stone,' immortalized by the Nō play Sesshō seki [殺生石] In this case, the connotations seem quite negative. Yet one tradition claims that it was brought to Shinnyodō in Kyoto and carved into a Jizō statue. This statue is today part of the mizuko [水子] cult for aborted or stillborn children, but is also the object of prayers for fecundity and for the health of young children."

The photos of the dōsojin to the left are shown courtesy of 663highland at http://commons.wikimedia.org/. The same with the photo above. |

|

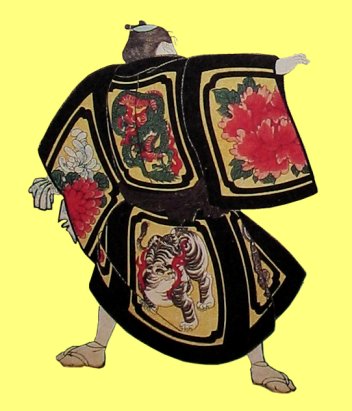

Dotera |

褞袍

どてら |

A padded, cold weather robe or kimono. Dotera are also called tanzen (丹前). Martin's Pocket Dictionary defines this garment as a padded bathrobe and many sites on the Internet describe it as being worn over an ordinary yukata. There is little verifiable information which we could find in English on this subject under the term dotera - almost nothing, in fact, but there is somewhat more under its alternative tanzen. Clearly from a number of sources the tanzen is also worn after a bath.

The image to the left is by Kuniyoshi. The one below is by Toyokuni III.

|

|

|

||

|

Dower, John W. |

ジョン・ダワー |

Author of The Elements of Japanese Design 1 This book is a great asset to anyone interested in traditional Japanese prints.

Born in 1938 in Rhode Island Dr. Dower received his doctorate from Harvard in 1972 in history and Far Eastern languages. He has taught at the U. of Wisconsin and the UC San Diego. He has won numerous honors including Pulitzer and National Book awards. |

|

E |

絵 え |

Picture, drawing, painting, sketch - Hugo Munsterberg said that the term 'e' was added to 'ukiyo' in ca. 1680 and became the term used for that entire genre until 1880. Of course, that is the term we still use today to describe the entire range of woodblock prints from that time. Hence, Ukiyo-e. |

|

Ebi |

蛯

えび |

Shrimp, prawn, lobster or crayfish. Ebi is a word that has numerous uses in combination with many proper names such as Ebizo, an actor's name.

One thing to note is that there are quite a few variations on the kanji characters which mean ebi. These include 蝦, 海老 and 鰕.

If you are interested in seeing more information and decorative examples of this motif then click on The Many Uses of Ebi. 1

In Mock Joya's Things Japanese (p. 465) it states "The ebi is regarded as a symbol of old age, the Japanese characters for ebi meaning 'the aged of the sea.' Thus ebi has been used on various happy occasions, not only on the table but also as ornaments. Lobsters used in New Year decorations were formerly preserved often as a charm for curing sickness and preventing evil fortune."

According to James Hall in his Illustrated Dictionary of Symbols in Eastern and Western Art (1994, pp. 34-5) by contrast, in China "...they are sometimes seen at the feet of the Kuan-yin... and symbolizes married bliss and harmony."

In Kodansha's Dictionary of Basic Japanese Idioms by Jeff Garrison (2002, p. 59) tells us that the phrase to "catch a sea bream with a shrimp" (海老で蛸を釣る) means "get a lot of bang for the buck" or "make a killing". (For a ton of stuff concerning the sea bream go to one of our Toyokuni III pages.) |

|

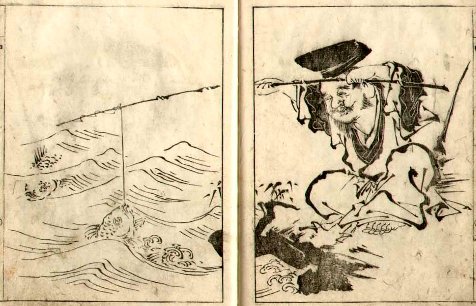

Ebisu |

恵比須 or 蛭子

えびす |

One of the Seven Lucky Gods, the Shichi-fukujin. A god of fishermen and prosperity. Of the seven he is the only one with a purely Japanese origin. His symbols are the fishing pole and the red tai, i.e., red sea bream. 1

See also our entry on hiruko, the leech child.

According to footnote 778 by Ivan Morris in The Life of An Amorous Woman it says that in the 17th century "...it was customary to offer 12 incense tapers to the God Ebisu." |

|

Ebiya |

海老屋 えびや |

A Yoshiwara brothel 1 |

|

Eboshi |

烏帽子

えぼし |

A tall lacquered courtier's cap. The image to the left is one of several variations used as a family crest or mon.

"In ancient days, all men, regardless of their position or occupation wore hats. Eboshi, a little pointed hat that was lacquered black, was usually tied on their heads. But sometimes, those who did not possess a proper eboshi or were too lazy to wear them, used to tie on their foreheads a piece of black paper cut in a triangle so that it looked as if they were wearing eboshi. From this developed the old custom of tying a triangular piece of white paper on a dead person's forehead. ¶ Of course, later, only nobles or those with court rank wore eboshi and commoners wore only sedge or other kinds of kasa."

Quoted from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, pp. 26-7.

|

|

"Kammuri were gradually replaced by the lower-ranking eboshi, a soft or hard roundish hat of silk or gauze, later made of paper covered with lacquer. Etiquette prescribed the wearing of a head covering when greeting another person, and eboshi, like kammuri, were such an integral part of a nobleman's dress that, despite their lack of function, they were often worn indoors, sometimes even while sleeping. During the Muromachi period (1333-1568), when the chommage hairstyle... came into use, the popularity of the eboshi declined, and it was worn thereafter only in ceremonies or rituals of the court or shrines." Quote from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 3, pp. 118-9, entry by Ishiyama Akira.

See also our entry on kammuri on our Kakuremino thru Kento index/glossary page.

"A type of black (occasionally gold) lacquered hat in various styles worn by priests, warriors, noblemen, shirabyōshi, and others." Shirabyōshi were "Female entertainers of the Heian and medieval periods who wore male court caps and while (shira) robes, danced to percussion accompaniment, and sang songs, including imayō ["...or popular songs of the Heian and Kamakura periods, sung professionally...or by aristocrats themselves at elite entertainments"]. They are portrayed in many traditional plays." Quotes from the glossary section of Traditional Japanese Theater: An Anthology of Plays, edited by Karen Brazell, Columbia University Press, 1998.

The Utamaro print shown above is from the Lyon Collection. As you can see Prince Narihira is wearing an eboshi. Click on the image to learn more about it.

In one example from this book there is a photograph of an actor portraying a Shinto priest wearing an eboshi. In another an actor wears the mask of a young woman with an eboshi atop 'her' head. Variations of this type of head wear are used in Noh, puppet and kabuki.

While looking for information to add to this entry I glanced at The Great Japan Exhibition: Art of the Edo Period 1600-1868 catalogue (p. 215 - item #237) which shows a "Helmet in the form of a court cap" from the Momoyama period. The description of item #236 describes that helmet as "Leathered covered in gold foil and cut with conventional foliage decoration, with the character mu picked out in black lacquer". [Mu is the character representing the Zen Buddhist concept of 'non-existence'.] This entry continues: "Court caps (eboshi) of various types were, like headcloths (zukin) much imitated by Momoyama period armourers. Thsi example, said to have been used by the warrior Uesugi Kenshin (1530-1578), was probably inteded to be mounted on a helmet in Hineno style which is also in the Uesugi shrine."

Uesugi Kenshin is tangentially referenced on our Yoshitaki page dealing with the theme of Yaegakihime. |

||

|

|

||

|

Edehon |

絵手本 えでほん |

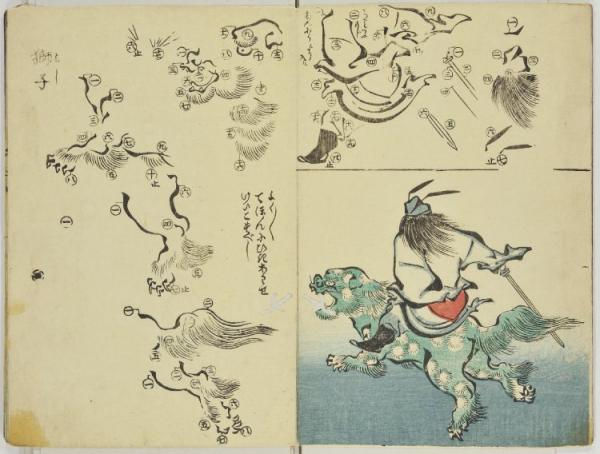

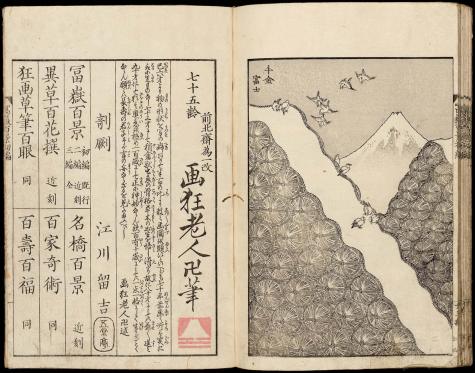

A drawing manual or copy book - According to Peter Russell Hokusai produced a number of edehon after being struck by lightning and changing his name to Taito. "Edehon manuals were now being produced by most painting schools in Japan, demonstrating how the growing population were in possession of more wealth and time to pursue new interests and hobbies. This edehon format would produce several important training manuals for proficient artists. As Hokusai lacked a large studio of assistants, and so few pupils that would continue his name for posterity, drawing manuals were no doubt an alluring choice of media, allowing him to eternalise his style for countless future admirers."

Page from a Hokusai edehon showing how to draw a picture of Shoki riding on a shishi. British Museum |

|

Edo |

江戸 えど |

Former name of Tokyo. Prior to its selection by Tokugawa Ieyasu in 1603 as the location of the new base for the shogunate Edo had been only a small fishing village. In time real power emanated from Edo while the imperial capital remained in Kyōto. |

|

Edo was originally a landed estate or shōen - located in the Kantō region. "Both the site and its founding family took the name Edo 江戸, meaning 'entrance to the inlet', from the physical features of the location - an inlet penetrating inland through the Hibiya and Marunouchi districts of present-day Tokyo. Thus at its very foundation Edo was marked by metonymy between the title of its principal occupants and the conditions of its physical environment." (Quote from: "Edo Architecture and Tokugawa Law", by William H. Coaldrake, Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 36, No. 3. (Autumn, 1981), footnote 13, p. 240) ¶ By the 15th century it was a thriving castle town or jōkamachi (城下町) under the control of Ōta Dōkan (1432-86: 太田道灌), a vassal of the Uesugi clan in Echigo. "By 1603, the year of the official foundation of the Tokugawa bakufu and three years after the battle of Sekigahara which gave the Tokugawa national supremacy, the site of Edo had been transformed from a swampy delta with a derelict castle and a scattering of fishing and farming villages, into an embryonic capital.'' (Ibid.) ¶ "Estimates vary, but by the 1720s the city had a population of at least 1.3 million, making it possibly the largest city in the world at that time. By comparison, eighty years later, in 1801, London had a population of 864,000, Paris 547,000, and Berlin 170,000.25 In addition to its spectacular increase in size by the early eighteenth century, Edo had also assumed a character of great distinctiveness. " (Ibid., p. 246) ¶ For security there were 28 major gateways or mitsuke (見附) into the city. "Paralleling in size and importance the monumental city gateways of the Roman empire, the Edo mitsuke were huge, multiple-entranced barbicans, richly decorated and massively fortified with finely finished ashlar walls. Their distribution around major points of the moat spiral pattern, in addition to controlling the flow of population within the city, was carefully correlated with the twelve zodiacal signs..." (Ibid., p. 248) ¶ Prior to the fire of 1657 Edo Castle had the largest stone foundation or tenshukaku ( 天守閣) in Japan. It stood 30% higher than that of the extant Himeji Castle. Ibid., p. 249. In fact, it may have been the largest castle ever built. Twice the size of Osaka Castle, the next largest. The stones of the tenshukaku had to be transported from great distances because there were no such stones to be found in the Kanto. This alone produced a great drain on the purses and the manpower of the daimyos. Because the daimyos were required by law to live in Edo much of the time they built their own elegant residences. In the 17th century these mansions were said to take up 60% of the city's land. (p. 250) ¶ In the first three days of 1657 fires raged throughout the city. 60 to 80% of it was burned including the tenshukaku and around 500 daimyo residences. Over 100,000 people died. This fire was much larger than the one which destroyed much of London in 1666. (p. 251) The overcrowding of certain districts was greatly responsible for the conditions which caused the destruction. By 1725 merchants and craftsmen "...comprised about 46.2% of the total population of the city but occupied only about 12.5% of the land area." (p. 252) ¶ After the fire of 1657 streets were widened, fire brigades were formed and many daimyos, temples and shrines were moved further away from the castle grounds. The tenshukaku was never rebuilt on the same scale although it had already been rebuilt once after the fire of 1639. (Ibid.) Besides the new shogun, Ietsuna, was only 17 and much of the power was now in the hands of a group of daimyo. (p. 253) In an effort to enforce frugality these daimyo also banned the use of roofing tiles. This was a recipe for disaster. In 1660 the ban was lifted for the daimyo. However, this general prohibition wasn't lifted removed until 1720 by Yoshimune. (p. 258) ¶ Before the Meireki Fire of 1657 many of the daimyo residences in Edo had elaborate and expensive gateways. During earlier times only the highest ranks were allowed to have entryways onto the main streets. This was meant as an indication of power. In fact, the term mikado (御門) translates literally as 'honorable gate'. However, after the great fire the ruling daimyo forbid the building of lavish, two story gateways. This was handed down by edict a month before they banned the use of tile roofs. (pp. 269-70) Other restrictions were established to make sure that the daimyo had a more obviously elevated status vis a vis the samurai in the service of the Tokogawa shogunate or hatamoto (旗本) and also that of the ordinary townsmen. "As early as 1613 an edict addressed to the townspeople has unequivocally laid down, 'Gateways should not be erected.'" (p. 272) ¶ However, Coaldrake points out that in the long run the prohibitions had little effect. (p. 273)

In the early 17th century "Most of the lords built three large residences in Edo, the more assuming holding over a hundred acres of land in the city, with the result that daimyo residences (which included the quarters of their retainers) took up almost half of the city's area. Most of the daimyo maintained hundreds and some even thousands of retainers and servants, accounting for a considerable part of the city's population." (Quote from: 'Sumptuary Regulation and Status in Early Tokugawa Japan’ by Donald H. Shively, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 25, (1964 - 1965), p. 149)

When the castle was being built Tokugawa Ieyasu did not follow the standard lay out of most castle towns - see our entry on jōkamachi. Instead he built along more ancient lines using the principles of feng shui (Ch. 風水) which were meant to control the malignant and beneficial forces of the cosmos. (Coaldrake, pp. 241-2) |

||

|

|

||

|

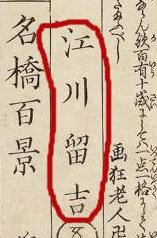

Egawa Tomekichi |

江川留吉

えがわとめきち |

Carver (active ca. 1834-49) who Hokusai requested that his publishers use because of his skill level, especially in portraying faces. Matthi Forrer also notes that Tomekichi was a friend of Hokusai's.

Above is an illustration of

Hokusai's the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The detail to the left shows the credit given to Egawa Tomekichi. It dates from 1834-35. |

|

Egoyomi |

絵暦

えごよみ |

Literally a "picture calendar" - a type of surimono. "...frequently distributed among friends to bypass government control of the issuance of official calendars as well as to serve as witty greeting cards."

Quoted from: Jewels of Japanese Printmaking: Surimono of the Bunka-Bunsei Era 1804-30 by Joan Mirviss and John Carpenter - cat. entry #13, p. 60.

"Calendar prints (egoyomi) first appeared in the early eighteenth century. They were customarily exchanged among friends at New Year, and have the numbers of the 'long' and 'short' months of the new lunar year hidden in some part of the design."

Quoted from: The Actor's Image: Print Makers of the Katsukawa School, Timothy Clark, Osamu Ueda and Donald Jenkins, Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 76, note 2.

We found the Harunobu print from 1765 shown to the left at Pinterest. It qualifies as an egoyomi because hidden within the girl's kimono is a pattern which disguises the characters for the long months - 2, 3, 5, 6, 8 and 10.

According to the British Museum this is the earliest known egoyomi dating from 1726. |

|

Most sources believe that the restrictions on the publication of calendars started in 1684. Previously there had been advances in astronomical measurements which brought doubts about the calculations being used. So a new system was put into effect in 1685. The new astronomical bureau was called the Tenmongata and did not supercede the older one but worked in concert with it in the production of each new calendar. "The Tenmogata took over the astronomical calculations... while the [older bureau] retained responsibility for the astrological elements." After 1684 privately printed calendars were prohibited. "Thereafter, all calendars were supposed to be calendrically and astrologically uniform." "...only recognised publishers could engage in this trade. They were generally known as calendar makers (rekishi 暦師) and there was a fixed number in the towns where they were permitted. In Edo there was a different system, for there was an established guild of calendar publishers: originally there were 28 of them but, as a result of an internal dispute, in 1697 the number was reduced to 11 and all others were forbidden to publish calendars." In 1841 all guilds were abolished under the Tempō reforms. ¶ Between 1697 and 1851 there were numerous edicts pronounced in an effort to control the calendar industry. "Several of these refer to the circulation of unauthorized calendars, presumably printed by those who were not members of the guild." They attempted to protect the guild's monopoly while "...they also testify to the supply of illicit calendars." ¶ There were two types of calendars considered illicit: the first were the 'abbreviated calendars' which were produced and released before the official one was approved by the Tenmnogata; the second were single-sheet calendars which "...were sold in shops and even hawked on the street corners, and offenders were to be severely punished..." because "...calendars were a 'serious matter'..." This "...almost certainly applies to the illustrated single-sheet calendars known as egoyomi 絵暦, and to some surimono prints which convey calendrical information."

The Japanese have long dai (大) and short shō (小) months "...which were cunningly concealed within the composition of the [egoyomi]. For the visually sophisticated connoisseurs who produced and exchanged the egoyomi, deciphering the hidden signs and meanings within the print were part of the enjoyment. The characters dai and shō appear in many ways; in the pattern of clothing, on the walls or in objects, as alternating large and small objects, hidden in text or as decorative letters or numerals. They were printed privately to coincide with the New Year and often included a suitable poem, were not for sale and were exchanged between friends often at gatherings of poetry circles. ¶ By the early 19th century, the tradition of exchanging egoyomi had evolved into a new type of commissioned print, surimono (literally 'printed thing'). (Quoted from: Japanese Popular Prints: From Votive Slips to Playing Cards by Rebecca Salter.)

Dan McKee wrote: "Surimono, in fact, did not develop out of egoyomi, but rather privately made egoyomi out of haikai surimono, and only then, kyōka surimono out of the twin streams of egoyomi and haikai surimono. These are facts that still have not achieved full awareness in Western-language scholarship, and even the most recently produced books on surimono, clinging futilely to the ukiyo-e mode, seem willfully ignorant of them." |

||

|

|

||

|

Ehon |

絵本

えほん

|

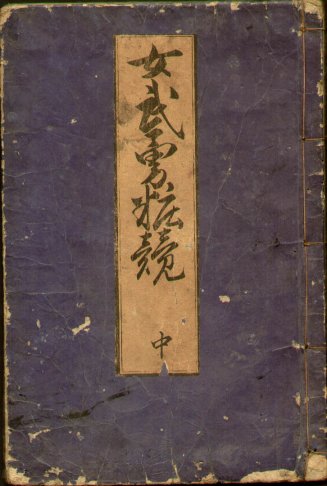

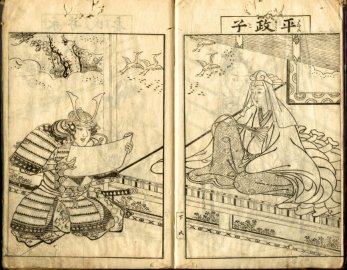

Literally "picture book": One could speak volumes about this subject, but for now I want to limit myself to two elements. The first is a general description of ehon. On the inside flap of Ehon: The Artist and the Book in Japan by Roger Keyes it states that ehon "...are part of an incomparable 1,230-year-old Japanese tradition. Created by artists and craftsmen, most ehon also feature essays, poems, or other texts written in beautiful, distinctive calligraphy. They are by nature collaborations: visual artists, calligraphers, writers, and designers join forces with papermakers, binders, block cutters and printers. The books they create are strikingly beautiful, highly charged microcosms of deep feeling, sharp intensity, and extraordinary intelligence."

The second is based on a comment Keyes made on page 140 which had always puzzled me: "Most Japanese books of this period [ca. 1800 and earlier] were printed on semi-transparent paper. Even though the sheets were printed on one side and folded in half, faint images would often show through. Most readers simply disregarded this, just as they overlooked the 'invisible' assistants dressed in black on the theater stage." (See our entry on kurogo.)

On the left are three illustrations contributed to this site by our great contributor E. The top one shows the cover of volume 2 of Settei's Onna Buyu Yoso-i Kurabe (Competition of bravery in women) of 1757. The middle and bottom ones clearly illustrate the point being made by Roger Keyes.

Thanks E!

|

|

Ekikyō |

易経 えききょう |

The I-ching or 'Book of Changes' - "The I-ching, one of the most ancient classics, probably originated as a collection of peasant omen interpretations. Although it incorporated a mass of material used in divination, it was eventually elaborated into a complex system of symbols adn explanations that has no counterpart in any other civilization. ¶ Japanese military strategists in warlike ages frequently used the I-ching in making crucial decisions. In peacetime under the Tokugawa regime, the book gradually lost its importance and became a handbook for unemployed samurai, who told individual fortunes. In fact, it is still the principal tool of Japanese street-corner soothsayers." Quoted from: A History of Japanese Astronomy: Chinese Background and Western Impact by Shigeru Nakayama, pp. 58-59. |

|

E-kyōdai |

絵兄弟

えきょうだい

|

"'Sibling pictures' (e-kyōdai) are works in which a small inset picture in a cartouche resembles the main part of the design in some way, creating an interesting comparison between the two. This kind of pictorial device was already used in works by Torii Kiyonaga dating from the 1780s, but the name comes from Santō Kyōden's comic novel (kokkei-bon) E-kyōdai (Sibling Pictures), published in 1794."

Quote from: The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, text volume, p. 181.

For years viewers have asked me what this or that cartouche means. Generally I can't tell them, but now at least I can in a small percentage of them.

The detail from a Yoshitoshi print to the left above shows a bijin under an umbrella in a snowstorm mimicked by what may be a peasant walking away from us in the cartouche above. Below that is a detail from a Kuniyoshi print of an actor wearing a summer robe, seated on a red cloth on the grass looking down at a turtle. The cartouche in the upper right of that print shows one of the propitious gods accompanied also by a turtle. We have added an enlarged detail of that section for greater clarity. (I have doctored the original Kuniyoshi image blocking out much of the detail work so you can focus on the more pertinent elements.)

For another example in a print by Chikanobu click on the number one in the column to the right. 1

|

|

The Elements of Japanese Design: A Handbook of Family Crests, Heraldry and Symbolism |

|

This book by John W. Dower published by Weatherhill originally appeared in 1971. The image to the left is the cover of the 1991 paperback edition. Excellent volume with tons of basic information and over 2,700 illustrations. However, it is not a good guide for identifying the specific crests, i.e., mons of individual kabuki actors. 1 |

|

Ema (also euma) |

絵馬

えま (えうま)

|

Today these are votive plaques given to a shrine or temple in hopes of getting one's wishes fulfilled or in thanks for a wish granted. Literally the word 'ema' means 'horse picture'. Originally horses had an ancient connection to Shinto beliefs: Horses served both as vehicles for certain gods and as messengers between the spiritual and temporal worlds. One of the functions of the ema was to end drought by bringing rain. In time the plaques displayed other hopefully propitious images, but they were still called ema. Their first known mention comes from several 11th and 12th century manuscripts and/or illustrated scrolls. In time the ema could be decorated with almost anything associated with a specific god or any human condition or endeavor. For example, if someone wanted to give up smoking, gambling or a sexual addiction the ema might include an image of a lock. Many emas were produced as wished for palliatives: Hemorrhoids relief might show a stingray; warts an octopus because in Japanese those words are homonymous; sexual dysfunction....well, I think you can guess what is shown then; etc.*

*While doing some other research we found that the Japanese word for wart was not a homonym for the word for octopus. Instead of wart it should have been a bunion or a callus.

Eventually larger emas were created and often showed off the skills of aspiring and established artists like several members of the Kanō school, Hanabusa Itchō, Shunshō, Hokusai, Toyokuni I and Kuniyoshi, et al. (Source: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 2, pp. 196-7, entry by Money Hickman)

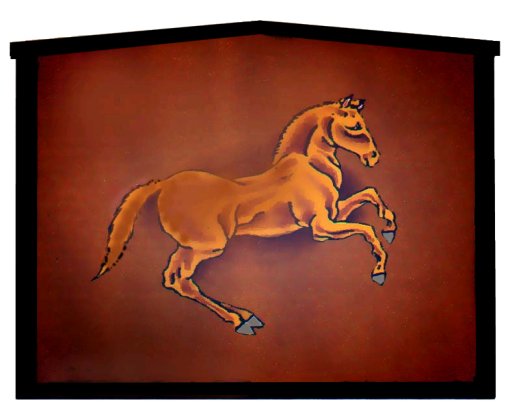

The graphic to the left above was contributed to our site by David Wilcox. The choice of a horse was mine. Thanks David! One note: often the symbolic image is accompanied by kanji characters, but neither David nor I felt that we were versed enough to know which terms would be the most appropriate. The image to the left below is a detail from a Kunisada print. And the image immediately below is from an ehon showing an artist who produced and sold ema. Notice that most of them are of zodiac figures. The coloring is mine.

"...the mother of Kūkai, who, as we will see, was worshipped at Jison-in (at the foot of Kōyasan) as a deity of childbirth, received ex-votos (ema) representing female breasts. Similar images were also offered at Mikumari Shrine in Yoshino, whose most important icon was Tamayorihime, the mother of the mythical ruler Jinmu... the name of the shrine, read originally as mikumari (water-dividing), came to be read as mikomori (protecting children). " (Quoted from: The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender, by Bernard Faure, published by Princeton University Press, 2003, p. 160) |

|

"...ema, or paintings of horses, usually on a wooden board, [were] made as offerings at shrines in lieu of real horses. Some scholars assume that ema developed in the medieval period, but Iwai Hiromi traces their development back to at least the mid-Heian period when 'shikishi ema' (literally, painted horses on decorative paper) offered to Kitano Tenjin Shrine are listed in a document dated to 1012 and 'ita ni kakitaru ema' (ema painted on boards) are mentioned in the Konjaku monogatari shu, a late-Heian-period collection of Buddhist didactic tales." (Quoted from: Critical Perspectives on Classicism in Japanese Painting, 1600-1700 by Elizabeth Lillehoj, pp. 141-2)

Brooklyn Museum

Ema were given to both Shintō shrines and Buddhist temples. "A large well-equipped shrine often had a separate building as the stable for a sacred horse, such as the one still seen at Ise Shrine. Horses were considered the favorite mounts of the Shintō gods. ¶ A votive horse's donor usually sought some personal favor from the gods in return for his gift to a shrine, or else assistance was sought for a problem affecting all the people. For example, if there was not enough rain for the crops, the gift of a black horse was appropriate., or a white one... in case of excessive rain and flooding. Since only the wealthiest nobleman could afford to donate real horses, the custom was eventually altered to permit offerings of wooden horse figures instead. Finally, pictures of horses became acceptable substitutes. The earliest mention of a votive horse picture is in the gift record of the Kitano Shrine in Kyoto for the year 1012." Quoted from: Mingei: Japanese Folk Art, the Brooklyn Museum, p. 24.

Kanō Sansetsu (1589-1651) at Kiyomizu-dera We found this at Wikimedia commons. |

||

|

|

||

|

Emakimono |

絵巻物

えまきもの |

Emakimono are illustrated narrative scrolls.

"The appearance of the yamatoe coincided with the development of such vernacular narrative prose forms as the romance, the diary, and the poem tale... It was not long before romances and similar works began to inspire paintings, which sometimes took the form of screen decorations but most often appeared as booklets (sōshi) or horizontal, hand scrolls (emaki[mono]) - small treasures for highborn ladies, who gazed at them while attendants read from related texts or told stories of their own invention. The horizontal scrolls were made of sheets of paper pasted together and attached to a mounting at one end and a roller at the other. Quite apart from the aesthetic value of their paintings, they were objects of art in their own right, with braided silk cords, richly colored mountings, rollers made of jade, crystal, or precious wood, and textual passages inscribed in exquisite calligraphy on paper flecked with silver and gold. That they were favored over the plainer sōshi is suggested by the frequency of their mention in works like The Tale of Genji, and by the fact that all the principal surviving Heian yamatoe are in emakimono form." Quoted from: The Cambridge History of Japan, vol. 2, p. 413.

The image to the left is a small detail from the Jigoku-zōshi (地獄草紙) showing one of the torments of Hell in the collection of the Tokyo National Museum. We found it at commons.wikimedia. |

|

Emma (also Enma) |

閻魔

えんま |

King of Hell, i.e., Jigoku in Japanese 1, 2

Emma rules the spirit world and all deceased souls appear before him. "He has a bright mirror before him. When we appear before him, we see ourselves reflected in it. It illuminates our entire being, and we cannot hide anything from it. Good and bad, all is reflected in it as it is. Emma-samma looks at it and knows at once what kind of person each of us was while living in the world. Besides this he has a book before him in which everything we did is minutely recorded. ...there is no deceiving him. His judgment goes straight to the core of our personality. It never errs. His penetrating eye reads not only our consciousness but also our unconscious. He is naturally legalistic, but he is not devoid of kindheartedness, for he is always ready to discover in the unconscious something which may help the criminal to help himself." (Quote from: Mysticism, Christian and Buddhist, by Daisetz Teitaro Suzuki, published by Forgotten Books, n.d., pp. 110-111) |

|

"In East Asia, a figure called Enma (J. Enma Ō; Ch. Yanmo Wang), a name with which most Japanese familiar, is believed to be the judge of the afterlife. He examines the deeds (karma) of the deceased and decides what their reward or punishment should be, just like an imperially appointed magistrate in a medieval Chinese court. King Enma is a modified form of the Indian deity Yama, but the element of bureaucratic judgment he introduces into the theoretically impersonal workings of the law of karma may be seen as a peculiarly Chinese interpretation of the Indian Buddhist tradition, revealing a heavy Taoist influence. Enma also belongs to a panel of judges known as the ten kings of hell. Each of these kings presides over his own court, through which the newly deceased must pass, receiving judgment from each in turn. ¶ King Enma, judge of the fifth court, is singled out in Japan for special attention and is closely associated with Jizō. King Enma never assigns a punishment worse than the sinner deserves, but sometimes this fearsome deity can be lenient when encouraged by Jizō." (Quoted from: Living Buddhist Statues in Early Medieval and Modern Japan by Sarah J. Horton, p. 116) |

||

|

|

||

|

Emonzaka |

衣紋坂

えもんざき |

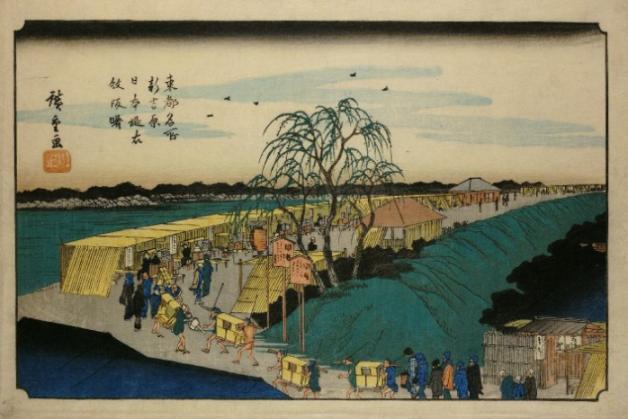

"The famous Emonzaka (Attire Slope or Lapel Slope) was the short, gently curving road on which Yoshiwara patrons descended from the road along the top of the embankment to the single great gateway into the walled enclosure of the licensed quarter. It is said to have been so named because it was here that visitors adjusted their attire to make themselves presentable before entering Yoshiwara." Quoted from: Early Modern Japanese Literature: An Anthology, 1600-1900, edited by Haruo Shirane, fn. 41, p. 642.

To the left is a Hiroshige print of Emonzaka from ca. 1840-42. |

|

|

鉛白 |

White lead |

|

Empō |

延宝

えんぽう

|

The reign period from 1673-1681. This era "...marks a decade of cultural activity in many spheres, Kabuki first came to feature full-length dramas, and the great Danjūrō I appeared in Edo - where, of course, Moronobu was a work consolidating the ukiyo-e style in his paintings and numerous illustrated books, while in Kyoto the works of Hambei were also published widely." Quoted from: "Historical Eras in Ukiyo-e" by Richard Lane in Ukiyo-e Studies and Pleasures, Society for Japanese Arts and Crafts, the Hague, 1978, p. 28.

|

|

Engawa |

縁側

えんがわ |

A veranda or porch which is protected by an overhanging eave and is generally an extension of an interior room.

The two images to the left were generously contributed to our site by E. Thanks E! Normally we only use one image, but both are so good we decided that we couldn't pass up one for the other. The top one is by Toyokuni I (豊国) and the lower one is a detail from an Eishi (栄之) print.

|

|

Enju |

槐

えんじゅ |

The Japanese pagoda tree or Sophora japonica: The flowers buds were used to create a traditional yellow dye. For more about this tree please visit out web log post at http://printsofjapan.wordpress.com/2009/06/20/traditional-yellow-pigments/.

This image was posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Warburg

The photo to the left of the enju tree was posted at Flickr by Joel Abroad. |

|

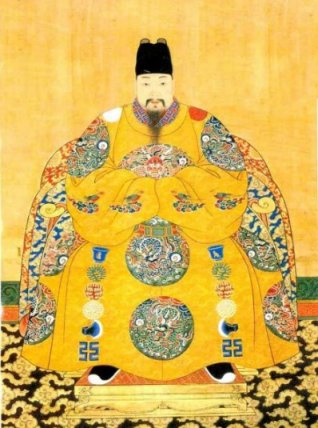

Recently we were looking for new information on enju when we ran across a rather odd reference. There is a story that, true or apocryphal - it doesn't matter, that the last Ming dynasty emperor committed suicide by hanging himself from one of these trees. In the spring of 1644 Beijing was under assault. The outer wall had been breached and the Chongzhen (Ch. 崇祯) emperor climbed the Hill of the Ten Thousand Years, the highest point in the city, to assess the overall situation. He saw smoke rising to the south. He went back to his compound and was said to have caused the death of much of his family and his devoted followers and then returned to the hill. "...he climbed the hill once more and hanged himself from the rafters of the newly built Pavilion of Imperial Longevity (Huangshou Ting). By the time his body was found the invaders had terrorised the court into submission. ¶ Later rumor claimed that the Chongzhen Emperor had in fact hanged himself from a sophora tree (also known as a scholar tree) on the eastern side of the hill. The offending tree, which was dubbed the 'criminal sophora' (zui huai) for allowing the emperor to die, has been replaced many times. To this day, tourists visit what is now called Prospect Hill to have their pictures taken in front of the stele marking the spot where the last Ming emperor is thought to have ended his days." Quoted from: The Forbidden City by Geremie R. Barmé, p. 145. (Below is a portrait of that emperor. It seems appropriately fitting that the main color is yellow, the imperial color, and particularly because the enju provides a yellow dye, but not necessarily one seen here.)

|

||

|

|

||

|

Etoki bikuni |

絵解き比丘尼 えときびくに |

Picture-explaining nuns. "Monks solicited alms in exchange for faith. Fund-raising and religious proselytization went hand in hand. Kanjin fund-raisers, including etoki hōshi (picture-deciphering monks) and told bikuni (picture-deciphering nuns), lived as itinerant mendicants among laypeople. Therefore the term kanjin, which originally meant an act of proselytization, acquired a meaning of begging and beggars." Quoted from: Explaining Pictures: Buddhist Propaganda And Etoki Storytelling in Japan by Ikumi Kaminishi, p. 103. |

|

"Among them developed one specific professional, etoki bikuni 絵解き比丘尼 (picture-explaining nuns), who was a female itinerant instructor utilizing visual sources to preach Buddhist dogmas to people of different genders and social standing, but especially targeting women audience. Asai Ryōi 浅井了意 (?-1691), the early Edo period popular literature writer, describes etoki bikuni in his Tōkaidō meisho-ki 東海道名所記 (Record of Famus Places Along the Tōkaidō, 1659:

As a result of this gender-oriented practice, the repertoire of etoki bikuni performance focused on particular dogmas and featured specific iconography, which enabled them to preach to a female audience. It was a relative novelty in the history of Buddhism, which traditionally excluded females from salvation." Quoted from: Visual Genesis of Japanese National Identity: Hokusai's Hyakunin Isshu by Ewa Machotka, p. 160. |

||

|

|

||

|

(The) Forty-seven Loyal Retainers |

四十七士 しじゅうしちし |

"The story of the vendetta carried out by forty-seven rōnin (masterless samurai) who remianed faithful to the memory of their former master..." |

|

Popularly known as the Chūshingura it was originally written for the puppet theater in 1748. "At the time the major Japanese dramatists were writing their plays for puppets rather than actors, a choice often attributed to dissatisfaction with the liberties that Kabuki actors often took with the texts."

Source and quotes from: Chūshingura: The Treasury of Loyal Retainers, A puppet play translated by Donald Keene, Columbia University Press, 1971, pp. ix-x.

Its full title is Kanadehon Chūshingura. "The first word means 'a copybook of kana,' a penmanship book for the writing of forty-seven symbols making up the Japanese syllabary." Written in kana, "...simple Japanese, rather than the high-flown style of the Confucian philosophers who praised the immortal forty-seven. But only pedants now use the full title of the play..."

Ibid., p. xi

For our entry on rōnin click on that highlighted word.

More extensive information will be added eventually on a page devoted to print with this theme. |

||

|

LINKS TO OUR OTHER INDEX/GLOSSARY PAGES Click on any of the pages listed below!

|

||

HOME

HOME