|

|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

|

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY Fu thru Gen |

|

|

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Fu, Fú, Fuda, Fudō Myōō, Fugu, Fuji, Fuji Musume, ,Fūjin, Fūkei-ga, Fukibokashi, Fukinuki, Fukinuki yatai, Fukiwa, Fukujusō, Fukura-suzume, Fukurokuju, Fukurotoji, Fukuseiga, Fukuwarai, Funa-manju, Funa-yado, Fundō, Fundoshi, Funpon, Fūrin, Fusuma, Futakata, Futame jigoku, Futatsu-tomoe, Ga, Gagō, Gaikotsu, Gama, Gama sennin, Gandō, Ganjitsu, Gankō, Ganpi (also gampi), Ganpishi, Gassaku, Ge, Gehō no hashigozori, Geisha, Gempuku (also genpuku), Genga, Genji kuruma, Genji monogatari, Genjina, Genpei, Genpei Nunobiki no Taki Genshoku Ukiyoe Daihyakka Jiten

普, 蝠, 札, 不動明王, 河豚, 藤, 藤娘, 風神, 風景画, 拭きぼかし, 吹貫き 吹抜屋台, 吹輪, 福寿草, 福良雀, 福禄寿, 袋綴じ, 複製画, 福笑い, 船饅頭, 船宿, 分銅, 褌, 粉本, 風鈴, 襖, 貳方, 両婦地獄, 画, 雅号, 骸骨, 蝦蟇, 蝦蟇仙人, 元日, 雁行, 雁皮, 雁皮紙, 合作, 下, 芸者, 元服, 原画, 源氏車, 源氏物語, 源氏名, 源平, 源平布引瀧, 原色浮世絵大百科事典 |

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Fu |

普

ふ

|

Nanushi censor's seal which represents the shortened version of the name of Fukatsu Ihei (普勝伊兵衛) used between VI/1842 and XI/1846. This seal appears on prints by Eisen, Hiroshige, Kunisada and Kuniyoshi among others. Richard Illing and the Rijksmuseum both give the dates for this seal as 1843-45.

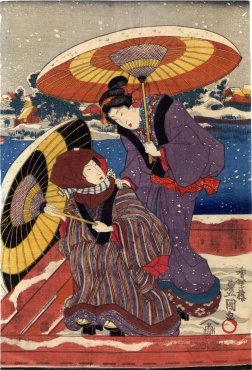

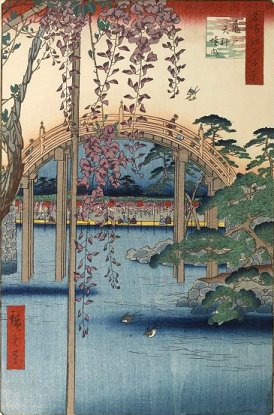

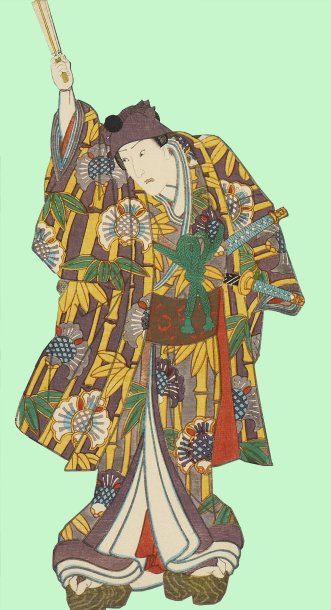

The image shown above carries the 'Fu' seal. It is from the Lyon Collection. To see a bigger image of this print click on it. |

|

Fú (a Chinese word) |

蝠

ふ (With a rising tone in Chinese unlike Japanese.) |

Chinese character, rising tone, for bat 1, 2 The Japanese for bat is kōmori (蝙蝠).

There is a Chinese herbal from the 16th century which stated that some bats live to be one thousand years old. "...white as silver [they] are believed to feed on stalactites, and if eaten will insure longevity and good sight." (Source and quote: Chinese Symbolism and Art Motifs by C. A. S. Williams, p. 61, 2006 edition) We mention this because of the similarity to stalactite eating in our entry on sennin. Go there and you will see what we mean.

Below is a picture of Honduran white bats posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Leyo. We couldn't find any stalactite eating 1,000 year old Chinese bats so we are using the next best thing. They don't look very old, do they?

"While generally despised in the West, the bat (komori) in East Asia is an emblem of good fortune. According to the French scholar Rolf Stein, the Taoist of ancient China believed that bats, in hanging upside down, concentrated key body essences that turned the animals white and made them immortal." Quoted from: Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design by Merrily Baird, p. 124. |

|

Fuda |

札 ふだ |

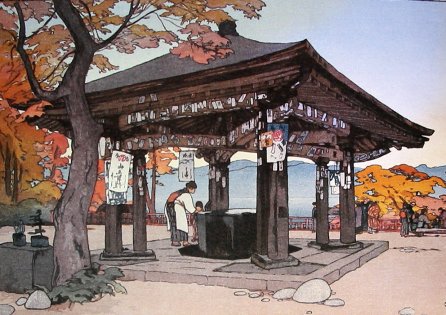

One definition of this term is "charm/talisman". Below is a detail from a Hiroshi Yoshida print, Utagahama (歌ヶ浜), from 1937 showing fuda applied to the beams and posts of the structure.

|

|

Fuda were originally applied to columns and beams at temples and shrines by pilgrims using niwaka, a kind of gelatin glue. "The act of visiting temples and shrines to paste fuda appeared to be more fun than devotional, and became particularly unpopular with those in charge of the buildings who saw it as a form of vandalism akin to grafitti nowadays. This is an even greater problem today, when fuda are mass-produced as sticky seals which can damage buildings; the original paste was at least the relatively harmless nori (rice paste). Many shrines and temples now outlaw the activity, although this can act as encouragement to renegade pasters who try it anyway. ¶ The art of pasting the fuda underwent technical development too. Originally they were stuck by hand, in low places, but it then came to be seen as a challenge to paste them as high up as possible. An extraordinary early technique was called nagebari; a pasted fuda was placed on a damp towel and hurled high up at a beam or the ceiling. This may have been effective, but it lacked the control over position and placement which was important for the Edoite competitive spirit inherent in pasting. The preference was for a prominent spot where everyone could see and appreciate not only the design of the fuda but also acknowledge that the person had visited. These spots were called hitomi (literally 'seen by people')..." but had the disadvantages of being exposed to the natural elements or removal by others and might last at most only a few years. Another method was called 'secret pasting' or kakushibari where they were hidden away from the wind and rain and other humans and therefore might last for 50 to 60 years undisturbed. ¶ In time someone invented a long extension pole of bamboo to which could be attached two brushes, the meotobake or 'husband and wife brush.' One brush would dust a spot clean and the other brush would moisten the area before the fuda would be applied. (Source and quotes from: Japanese Popular Prints: From Votive Slips to Playing Cards by Rebecca Salter, pp. 96-97)

Fuda can also mean 'ticket'. Samuel L. Leiter wrote: "Edo-period theatregoers were sold a ticket in the form of a flat, oblong, wooden board called a fuda (or torifuda). It was 7 sun (about 10 inches) in length, and 2 sun, 1 bun (about 3 1/2 inches) in width." |

||

|

|

||

|

Fudō Myōō |

不動明王

ふどう.みょうおう |

Originating in the Hindu pantheon he came to be regarded as one of the five wise kings who despite his stern countenance is a saver of souls. His attributes are the sword with which he fights evil and the rope which he uses to lasso individuals who can be saved.

Anyone familiar with Fudō Myōō knows that he is always accompanied by flames. Daisetz T. Suzuki tells us why: "Acala's [the ancient Indian name for Fudō Myōō] anger burns like a fire and will not be put down until it burns up the last camp of the enemy: he will then assume his original features as the Vairocana Buddha, whose servant and manifestation he is. The Vairocana holds no sword, he is the sword itself, sitting alone with all the worlds within himself."

Quote from: Zen and Japanese Culture, Daisetz T. Suzuki, Bolingen Series LXIV, Princeton University Press, 1993, p. 90. 1 |

|

Patricia Graham in her paper Naritasan Shinshōji and Commoner Patronage During the Edo Period notes some of the prominent iconographic features of Fudō. "He either stands or sits on a rock with his body framed by a aura of fire. His facial expression is fierce, with one eye peering up and the other down and two fangs, also pointing in opposite directions. He usually holds a sword in his right hand to slash demons and a cord in his left to bind them and also to capture devotees and lead them into Paradise."

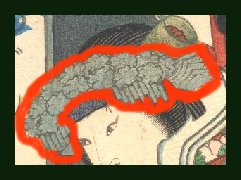

The detail shown above is from a print by Toyokuni III portraying an actor as Fudō. Notice the fangs - one pointing up and one down. The eyes are not following true to form. Instead one eye is crossed - a dramatic technique invented by one of this actors predecessors. The image below is a detail of a photo posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Kenpei. It is of a sculpture of Fudō of indeterminate age but clearly modern. But that is not the point - the fangs are pointing in different directions. Again the eyes are not so easily read.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Fugu |

河豚

ふぐ |

Blowfish, pufferfish - "There was a good trade in aphrodisiacs for those who could afford them. Extracts and drinks were made from Chinese and Korean ginseng roots mixed with local herbs that could still be found along the banks of Edo's rivers, tiger balm and pulverized rhinoceros horn. Fugu, the Japanese blowfish, purportedly another aphrodisiac, was a favourite among courtesans and wealthy guests, though the poison from the fish, if not properly extracted, could be fatal. The risk seems only to have increased the thrill of sampling the tissue thin slices of fish." Quoted from: Tokyo A Cultural History by Stephen Mansfield, p. 35.

The image to the left was posted at Flickr by furibund. The image shown above was also posted at Flickr, but this one was put there by Kojach. |

|

"Blowfish is a generic name for several members of the fish family tetraodontidae, a fish that can swell itself to several times its normal size by swallowing air or water. The tetraodontidae family has 187 known species, of which about fifty can be found in Japan, and about ten of which are regularly eaten there. The most common blowfish served in Japan is torafugu (Takifugu rubripes), or tiger blowfish, the largest among Japan’s species. It is also one of the most poisonous. ¶ The poison, tetrodotoxin, is highly concentrated in the organs, especially the liver and the ovaries. Generated by bacteria that live in the fish, the poison is 1250 times deadlier than cyanide and 160,000 times more potent than cocaine. One fish can kill thirty adults. ¶ A small amount of poison creates a stinging numbness in the lips, tongue, and extremities. A bit more produces the same effect, and eventually paralysis, in the lungs, which leads to death. There is no known antidote; the treatment usually consists of pumping the patient’s stomach, placing him on artificial respiration and intravenous hydration, and feeding him activated charcoal to bind the toxin." Quoted from: 'Haley and the Blowfish' by Mark West in the Washington University Global Studies Law Review, p. 429.

"The folk story holds that when Hideyoshi Toyotomi sought to conquer Korea in 1592, he amassed a force of 158,800 troops on Kyushu, where blowfish was a favorite dish, for the task. Many men died of blowfish poisoning before they reached Korea, and as a result, Hideyoshi banned consumption.... The story is often told, but I find no evidence of it in primary or secondary academic sources. ¶ A ban appears to have been in place during the Tokugawa period (1603–1868), but its scope and enforcement is questionable. Englebert Kaempfer, physician to the Dutch embassy in Nagasaki from 1690 to 1693, noted that 'Soldiers only and military men, are by special command of the Emperor forbid to buy and to eat this fish. If any one dies of it, his son forfeits the succession to his father’s post, which otherwise he would have been entitled to.'.... ¶ The standard account holds that the blowfish ban was lifted during the Meiji period (1896–1912) but reinstated by the legislature in either 1882 or 1885 pursuant to the Order for the Disposition of Petty Crimes... The standard account further holds that in 1888, Prime Minister Hirobumi Ito traveled to his hometown in Yamaguchi prefecture, Japan’s blowfish capital, and sampled the dish. He immediately lifted the ban—but only in Yamaguchi prefecture.... I find no evidence for this often-told story. The Order for the Disposition of Petty Crimes was enacted in 1885, but it is a general statute that contains no mention of blowfish or anything resembling blowfish.... But Prime Minister Itō had no authority to legislate or otherwise dictate policy in the Yamaguchi prefecture, and there is no primary source evidence that he did so." (Ibid., fn. 36, pp. 432-3)

On August 21, 2010 Laura Roberts wrote an article for The Telegraph about deaths which shocked the Japanese: "In 1975 Bandō Mitsugorō VIII, a Japanese kabuki actor, died of severe poisoning when he ate four fugu livers (also known as pufferfish). The liver is considered one of the most poisonous parts of the fish, but Mitsugorō claimed to be immune to the poison. The fugu chef felt he could not refuse Mitsugorō and lost his license as a result."

Today fugu can be farm raised to be poison free. One can even eat its liver. |

||

|

|

||

|

Fuji |

藤

ふじ

|

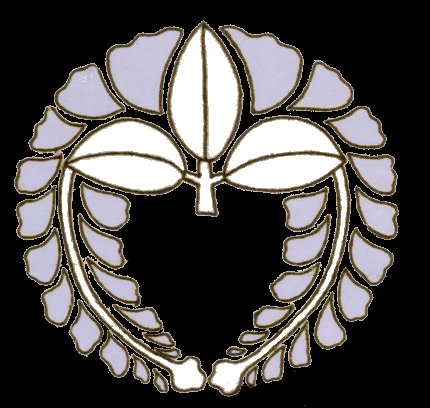

Wisteria: "Originally a wild mountain plant that twined itself around trees....was domesticated at an early date, and by the late Heian period was celebrated at parties sponsored by Japanese aristocrats. [Its]...trailing racemes of purple flowers, among the most popular of family crest and general decorative motifs..."

"The Fujiwara, whose name contains the ideograph for wisteria, was the most prominent court family in the Nara and Heian periods and had a tutelary relationship with those two religious institutions." (Quoted from: Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design, by Merrily Baird, p. 67)

|

|

While this mon was used mainly by 97 different branches of the Fujiwara clan there were others who used it as well.

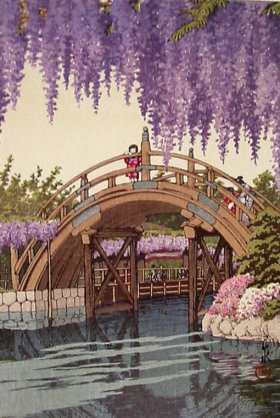

Above is a detail from a May 1932 print of the wisteria at Kameido.

"Transcribed literally, the Fujiwara surname means 'field of wisteria,' and in both their textile and landscape design, the clan made prominent display of the wisteria. Despite this natural association, however, Japanese genealogies reveal that in the later centuries only a small percentage of the families descended from the greatest of Japanese aristocratic lineages actually used the wisteria as their main family crest. Families with 'fuji' as a part of their name sometimes combined calligraphy and design, as in the crest of the Kato family... where the character for ka was enclosed in a circular wisteria pattern (to is the Chinese reading for wisteria). Families expressing devotion to the Kumano Shrine also used wisteria, one of the plants associated with it." (Quoted from: The Elements of Japanese Design by John W. Dower, p. 82)

Above is the same scene as the Hasui, but from a somewhat perspective. This one is by Hiroshige and the original is in the Brooklyn Museum of Art.

The Kameido (亀井戸) Shrine is a popular spot in the Edo/Tokyo area devoted to Sugawara no Michizane. In 1908 Florence Du Cane wrote: "Perhaps the most popular haunt of the pleasure-seeker in the month of May is the celebrated Kameido Temple in Tokyo. Words fail me to describe the beauty of the scene: it is a real feast of fuji; the long purple trails cover the large trellises, the wide rustic galleries, and connect the little matted restaurants, where hosts of people throughout the day sit feasting under the purple roof and feeding the goldfish in the lake. The matted benches are set out on a thick mauve carpet of fallen blossoms, and the little maids seem to have a never-ending task in sweeping away great heaps of freshly fallen flowers, as though fearing that their guests will be smothered by them.... I sat surrounded... by the blossoms, inhaling their delicious scent and listening to the droning of bees, I could graze across the water at the reflection of a never-ending vista of mauve blossoms reaching on one side to the celebrated round wooden bridge, the delight of children, who seemed to cross it in one endless stream, and on the other to the fine old temple, where a few ancient pines are placed just where they will best harmonise with the long purple blossoms. The late sweet-scented white variety will prolong the fuji season by a few days; their glory is but short-lived, a few days and then the colour begins to fade.... I turned away sadly, not forgetting the Japanese theory that the wistaria loves saké. So strong is their belief, that I was told if you set a jar under the plant, its spray will grow longer from its desire to reach the jar; so I ordered my little cup of saké, sipped it, and then emptied the cup on the roots, according to their custom, hoping that I might help to contribute to its great size and beauty." (Quoted from: The Flowers And Gardens Of Japan by Florence Du Cane, pp. 147-9)

Some of the individuals and families that used the fuji as their crest or mon: the Noda (野田); the Kitagawa (喜多川); the Kubo (久保); the Sugiyama (杉山); Katō Yoshiaki (加藤嘉明) as daimyō at Minakuchi in Omi; Gotō Matabei (後藤又兵衛); Natsuka Masaie (長束正家); the Naitō (内藤) as daimyō at Nobeoka in Hyuga, as daimyō at Murakami in Echigo; as daimyō at Takato in Shinano, as daimyō at Unagaya in Mutsu, as daimyō at Korano in Mikawa, as daimyō at Iwamurata in Shanano; the Naruse (成瀬) as daimyō at Inuyama in Owari; the Andō (安藤) as daimyō at Iwakidaira in Mutsu; Itō (伊藤); the Katō (加藤) as daimyō at Osu in Iyo; the Tōyama (遠山) as daimyō at Naeki in Mino; Naitō Masanari (内藤正成) as daimyō at Murakami in Echigo and also at Nobeoka in Hyuga; the Shibata (柴田); and Andō Naotsugu (安藤直次) as daimyō at Tanabe in Kii. (Source: Mon: The Japanese Family Crest by Kei Kaneda Chappelear and W. M. Hawley, p. 9) And more families and individuals who used a wisteria crest: the Fukatsu (深津); the Kawai (川井); the Tsubouchi (坪内); the Kamiya (神谷); the Masaki (正木); the Nigao (仁賀保); Hasegawa (長谷川); Ōkubo (大久保); Shinjo (新庄) as daimyō at Aso in Hirachi; Uchida (内田); Kuroda Nagamasa (黒田長政) as daimyō at Fukuoka in Chikuzen and as daimyō at Akizuki in Chikuzen; the Shitatei (下田丁); the Uratsuji (裏辻); Ōmikado (大炊御門); Konagaya (小長谷): Higashirokujō (東六條); Kujō (九條); Nagai (長井); Chiba (千葉); Kawamura (川村); Tsuji (辻); Ōkubo Hikozaemon (大久保彦左衛門) as daimyō at Karasuyama in Shimotsuke; the Itami (伊丹); the Hosoda (細田); the Suzuki (鈴木); the Makita (蒔田); the Nijō (二條); Ichijō (一條); Nishirokujō (西六條); the Daigo (醍醐); the Sagara (相良); the Tominokōji (富小路); the Matsuzono (松園); the Tōyama (とうやま); the Andō as daimyō at Taira in Mutsu; and Ōkubo Tadayo as daimyō at Odawara in Sagami. (Ibid., pp. 10-11)

In the Japan Encyclopedia by Louis Frédéric (p. 196) it says: "Wisteria (Wisteria floribunda), climbing leguminous plant with showy purplish flowers. There are many varieties: cultivated (kushakufuji, shirobanafuji, with white flowers; akabonofu, with pink flowers), which climbs in a clockwise direction, and wild (yamafuji, Wisteria brachybotrys), which climbs counterclockwise."

Below is a haiku by Bashō:

wisteria beans: I'll make them my poetry with the blossoms gone

fuji no mi wa/ haikai ni sen/ hana no ato

In the Man'yōshū is a poem by Yakamochi (718? - 785). Part of it reads

I love the wisteria that scatter At the brush of the cuckoo's wing; I pluck the petals off And tuck them in my sleeves - If they stain they stain.

Yakamochi went rowing on Lake Fuse and wrote

Waves of wisteria Reflect on the clear sea - The pebbles on the bottom Are like jewels. |

||

|

|

||

|

Fuji Musume |

藤娘 ふじむすめ

|

The Wisteria Maiden - "The Wisteria Maiden was originally one of five dances performed one after the other in rapid sequence by the same dancer who effected multiple quick changes of costume, wig, and makeup. These transformation dances (hengemono) were very popular in nineteenth-century kabuki and exhibited the virtuosity of the actor- dancers. The entire dance from which Wisteria Maiden derives was known as Ōtsu of the Ever-Returning Farewells (Kaesu Gaesu Nagori no Ōtsu). It featured characters that appeared in the popular, naive folk pictures known as Ōtsu-e (Ōtsu pictures), which were sold in the Ōtsu region to tourists visiting the area around Lake Biwa. In the original dance, Seki Sanjūrō II (1786-1839) performed as five different characters: the wisteria maiden, the god of calligraphy, a footman (yakko), a boatman, and a blind man. The only dance that has survived is the first, Wisteria Maiden." Quoted from: Kabuki Plays on Stage: Darkness and Desire, 1804 - 1864, volume 3, p. 166.

The image shown above of the Fuji musume was posted at Flickr by cheran.

The image to the left is from the Lyon Collection. |

|

In "....1937, when Onoe Kikugorō VI (1885-1949), known as 'the god of the dance,' changed the entire format of Wisteria Maiden. It is not known in exactly what setting the first dance was performed; perhaps it was in front of panels representing the five Ōtsu pictures, which came alive as the actor stepped out of the panels to dance. Kikugorō changed the decor to the brilliant one used today used today: the trunk of a pine tree from which bright purple wisteria blossoms fall in dazzling profusion. He also replaced the 'Itako Dejima' section with a newly composed 'Fuji Ondo' (Wisteria Dance), based on a folk song and dance. It stresses the more mature, experienced, womanly feelings of the wisteria maiden and is danced twice, the second time in slightly inebriated fashion, since during the first round the maiden has partaken of sake. The skill of the dancer is revealed in his ability to express drunkenness without vulgarity." (Ibid.)

"The lyrics of Wisteria Maiden are a tissue of allusions, esoteric references, and plays on words, thus making ready comprehension virtually impossible, even for the scholar. Because the meaning is somewhat tenuous, the movement patterns (furi) are often less realistic than those in more down-to-earth dances. Instead, they tend to suggest emotions, character, and attitudes in a general way. The lyrics pile meaning on meaning..." (Ibid., p. 167) |

||

|

|

||

|

Fūjin |

風神 ふうじん |

The wind god is often paired with the thunder god. "To protect temples from destruction by thunder and storm, statues of Raijin and Fujin are sometimes placed at the temple gates. Fujin is the god of wind, and it can be easily identified by the large bag of wind it carries over his shoulder." Quoted from: Things Japanese by Mock Joya, p. 345.

The image shown above is a detail from the right-hand side of a set of screens at the Tokyo National Museum.

The artist is Ogata Kōrin

(尾形光琳). We found it posted

The image to the left is a detail of a tattoo from a print by Kuniyoshi. To see the full image in the Lyon Collection click on the red Fūjin. . "In Japanese demonology Fujin is a demonic and the eldest of the Shinto gods. Demon of the wind and present when the world was created, he appears as a dark and terrifying figure. He carries a large bag filled with wind over his shoulder. He wears leopard-skin clothes." Quoted from: Encyclopedia of Demons in World Religions and Cultures by Theresa Bane, pp. 140-141. |

|

|

||

|

Fūkei-ga |

風景画

ふうけいが |

Landscape print or picture - Pure landscape views in prints did not become popular until restrictions on travel for ordinary Japanese had been loosened. Now there was an interest in what unknown places looked like and artists like Hiroshige and Hokusai filled that bill.

The image to the left by Hokusai was posted at Flickr by Cea. |

|

Fukibokashi |

拭きぼかし

|

"Bokashi can be achieved in two ways using brushed pigment... and by carving itobokashi... Itobokashi is more consistent but the gradation of the colour is not as marked. Brushed or wiped bokashi (often called fukibokashi) has a softer feel to it but as the brushing of each block may vary slightly, it is hard to achieve complete constituency across an edition. Fukibokashi has the advantage that it can be printed from any flat block; for example, the sky would be printed first in pale blue then the same block used for the darker bokashi on top. ¶ Small areas can be printed using a hake, larger areas, a brush or folded cloth. Printing large editions, the block would need to be washed every now and again to prevent clogging. A successful bokashi shows the combination of wood, pigment and paper." Quoted from: Japanese Woodblock Printing by Rebecca Salter, pp. 102-103.

"In the beginning of Anyei, Toriyama Sekiyen devised a method of gradation colour-printing called Fuki-bokashi no saishiki-zurit which he first applied in practice to a two-volume folio book entitled Sekiyen gwafu (alternative tide, Toriyama Hiko), which appeared in 1773. This method was but rarely resorted to during the remainder of the 18th century; but it was largely employed, by Hokusai and Hiroshige especially, during the next century. The grading was effected by a judicious wiping of the block upon which the colour had been spread. Sekiyen also illustrated a series of books, each of three volumes (in which he applied the fuki-bokashi method to monochrome), under the generic title of Hyakki-yagiyō, dealing with the night wanderings of demons." Quoted from: Japanese Colour Prints by Laurence Binyon, pp. 71-72.

The image to the left comes from the collection of Waseda University. It shows a Sekien illustration published in 1805. Sekien died in 1788. |

|

Fukinuki |

吹貫き

ふきぬき |

"A fukinuki... was a hollow streamer formed of strips of cloth attached to a ring, which would blow in the wind. They would often be used as standards but sometimes were used instead of a nobori as a primary device." Quoted from: O-umajirushi: A 17th-Century Compendium of Samurai Heraldry, p. xvii.

We found the detail of an image seen to the left at Pinterest. The image below is a detail from a triptych by Kuniyoshi in the Lyon Collection. Click on it to see the full triptych.

|

|

Fukinuki yatai |

吹抜屋台 ふきぬきやたい |

Bird's-eye-view used in Japanese art where the roof has been removed to allow views of interiors. "Paintings of indoor scenes depict them from an aerial perspective of modest elevation, famously 'blowing off' the roofs (fukinuki yatai) and the architectural cross-beams to provide unobstructed views of the interior." Quoted from: Envisioning the Tale of Genji: Media, Gender, and Cultural Production by Haruo Shirane, p. 66.

Louis Frederic in his Japan Encyclopedia (p. 214) gives basically the same definition of fukinuki yatai: " 'Houses with blown-off roofs,' an artistic convention used in paintings in the Yamato-e style, in which houses, seen from above, were drawn without a roof so that the interior could be seen."

The image shown above is a detail from a hand scroll in the Kyoto National Museum posted at commons.wikimedia.org. |

|

Fukiwa |

吹輪

ふきわ |

An elaborate headdress worn by a princess.

Professor Samuel Leiter translates fukiwa as literally meaning "blow circle." A "...beautiful wig worn mainly by princesses (hime or himesama) in jidaimono. The large, round topknot (mage) contains a red hand drum-like ornament inserted horizontally through it, with a red bow and decorative starched paper strips (takenaga) hanging from beneath the topknot. Flower combs with silver plum blossoms and butterflies are inserted at the front."

Quoted from: New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of kabuki jiten, compiled by Samuel L. Leiter, 1997, p. 99. 1

The floral comb at the front of the wig is referred to as a hanagushi (花櫛). The entire wig is called a mage-fukuwa. |

|

Fukujusō |

福寿草

ふくじゅそう

|

Literally "the grass of luck and longevity" and also referred to as the "pheasant's eye". This is the Adonis flower a symbol of the New Year and prosperity. Hokusai included it in more than one surimono.

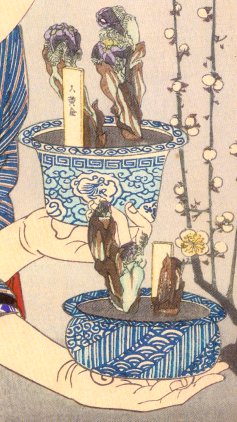

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Yoshitoshi where a woman is trying to decide between the purchase of two different Adonis flower selections.

In Mock Joya's Things Japanese (pp. 193-4) it states that the "Fukuju-so (Adonis amurensis) has bright little golden blossoms. Its buds are silver gray, the leaves are green, but its blossoms are bright gold. Its name in Japanese means 'wealth-long-life-plant.' Because of its golden blossoms and also its lucky name, the flower is much admired by the people who use it especially for decorating their homes for the New Year celebration." This plant prospers in colder climes and is said to have originated in Hokkaido which was called Ezo-ga-shima. There is a story that says that "Once there lived in Ezo a beautiful goddess called Kunau. Her father betrothed her to the god of the earth-mole. But she did not care for the groom-elect selected by her father. Her refusal to marry the god of the earth-mole so angered her father that she was reduced to becoming a common wild blossom as punishment for disobeying her father. ¶ Thus she turned into a blossom which came to be known as Kunau or Kunau-nonnon. ¶ By the Ainu people, fukuju-so is still called Kunau. The tale of the Goddess Kunau is related by Ainu parents to their little daughters as a lesson teaching them the duty of obeying their parents. But if they were sure to be transformed into such beautiful blossoms, Ainu maidens might oppose the command of their parents to marry and follow the example of the Goddess Kunau."

These photos are shown courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. |

|

Fukura-suzume |

福良雀

ふくら-すずめ |

A stylized motif of a sparrow, often seen from above with its wings and tail feathers spread outward. As a physical form it is often used as a child's toy.

To the left is a detail from a Toyokuni III print of an actor as Yorikane. Look closely at his robes and you will see the fukura-suzume motif. Also, see the detail of the detail below.

This term also describes one of the ways of tying an obi. |

|

Fukurokuju |

福禄寿

ふくろくじゅ |

One of the Seven Propitious Gods. He is the god of wealth and longevity. 1

The image to the left is a netsuke posted at Flickr by Marshall Astor - Food Fetishist. |

|

Fukurotoji |

袋綴じ ふくろとじ |

This is a binding method in

which "...in which recto and verso were printed on the same folio and |

|

Fukuseiga |

複製画 ふくせいが |

A reproduction print - "The later nineteenth century likewise corresponded with the rise of a 'pure' reproduction (fukuseiga) industry aimed at recreating masterpieces of the past from new blocks. Among the best documented of these Meiji reproductions are the surimono (privately printed works) made in Akashi, a small town in Hyogo prefecture, by the otherwise unknown publisher Tsumura and first appearing in the early I890s. " |

|

"A new phenomenon emerged in the 1890s parallel to the activity of these artists that comprised three types of reproductions. In the first, publishers used paintings as source materials for woodblock prints, the second was reproductions of classic ukiyo-e prints and the third was the reproduction of paintings for art publications. Examples of the first category are found in the numerous square shikishibon (c. 22.8 x 23.5 cm) issued by the Tokyo publisher Matsuki Heikichi (Daikokuya) from around 1890 based on paintings by ukiyo-e, nongo (literati) and Maruyama-Shijo artists. Some of these prints were pirated from paintings with fake signatures of artists long dead, among them the ukiyo-e masters Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-18S8) and the nongo artist Nagamachi Chikuseki (1747-1806). Yet these 'painting reproductions' also included designs from livingartists such as Ogata Gekko (1859-1920),Yoshitoshi's student Tsukioka Kogyo (1869-1927) and the elusive Seiko, a possible but unidentified pupil of Watanabe Seitei (1851-1918)... ¶ The later nineteenth century likewise corresponded with the rise of a 'pure' reproduction (fukuseiga) industry aimed at recreating masterpieces of the past from new blocks. Among the best documented of these Meiji reproductions are the surimono (privately printed works) made in Akashi, a small town in Hyogo prefecture, by the otherwise unknown publisher Tsumura and first appearing in the early I890s. Other examples are the fabulous copies of the chiiban-format prints (c. 18x 25 cm) by Suzuki Harunobu (c. 1725-70) and oban-format prints (c. 39 x 24 cm) such as Hokusai's A tour of waterfalls in various provinces (Shokoku taki meguri) released by Matsui Eikichi (Matsueido). The erotic imagery of shunga by eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century masters Hokusai, Kitagawa Utamaro (1753-1806),Katsukawa Shuncho (act. c. 1780-1801) and Kikugawa Eizan (1787-1867) was the subject of a number of reproduction series printed from re-cut blocks in stronger aniline and ecoline pigments. Virtually nothing is known about many of the publishers of these works but it isclear that business was buoyant.' Another form of reproductive practice extended to the art journals emerging at this time, such as Japan's longest running art publication, Kokka (est. October 1889),whose printed reproductions of paintings were of an extremely high quality. This aspect is singled out in an announcement of Kokka in the newspaper Tokyo Asahi shinbun, and praised the artisan KimuraTokutarō for his creatively carved woodcuts (chozo mokuhan) and Ogawa Isshin for his collotypes (shashinban). Technically comparable reproductions were similarly included in the luxurious books and portfolios by the Tokyo publisher Shinbi (Shimbi) Shoin from 1899 and advertised in newspapers from the early twentieth century onwards." Quoted from: 'Waves of Renewal, Modern Japanese Prints 1900-60: Selections from the Nihon no Hanga Collection, Amsterdam'. |

||

|

|

||

|

Fukuwarai |

福笑い

ふくわらい |

During the Edo period a game called fuku-warai (福笑い), a kind of blind man's buff, was played where children, generally, would wear a mask of Otafuku/Okame. The mask would have slits at the eyes, but the children wearing the mask were supposed to have their eyes shut. Another version of this game involved pasting the parts of a face all over a mask in the wrong places. The purpose was to make the participants laugh. They did. |

|

Funa-manju |

船饅頭 ふなまんじゅう |

"Boat dumplings" - lower class prostitutes who plied their trade in boats along the sides of canals or rivers and not in the authorized, i.e. licensed, red-light districts like the Yoshiwara. |

|

Funa-yado |

船宿

ふなやど |

Kenkyusha's New Japanese English Dictionary defines funayado as "...a shipping agent... a keeper of pleasure boats; a boat-house... an inn for sailors... a river-side teahouse."

There is very little written in English on this topic. De Becker wrote: "It is recorded that since the era of Genroku (1688-1703) the keepeers of funa-yado (a sort of tea-house where pleasure boats are kept and let out on hire for excursions and picnics) used to arrange for guests to go and come in their river-boats, "and among the sights of Yedo were the long lines of boats floating up and down the river with gaily-dressed courtesans and the jeunesse dorée of the city in them." "

To the left is a Kunichika print which has "Funa-yado" in the title. It is dated from 1878. |

|

Fundō |

分銅

ふんどう

|

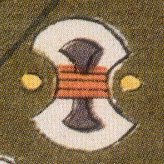

A weight or counterweight: One of the symbolic lucky treasures.

To the left (above) is an image of a fundō from the robe of a beautiful woman or bijin in a print by Eishō. Her kimono is covered with this and other treasure symbols. Often seen along with other treasures as decorations on ceramics, fabrics and other items.

The image on the bottom left is another variation on the fundō motif - also found on an Eishō print.

In Japanese Art Motives (1917, p. 155) Maude Rex Allen wrote: "The fundo is a weight used by tradesmen. It is symbolic of commerce."

The bottom image to the left was found at Pinterest. It comes from the Tōyō Measurement Equipment History Museum (東洋計量史 資資料館). |

|

Fundoshi |

褌

ふんどし |

Loincloth: "...men's underwear made of a long piece of cloth. Fundoshi for an everyday use is a white cotton cloth, though it is rarely used today. The one worn by sumō wrestlers in the ring is made of colored tight-woven silk."

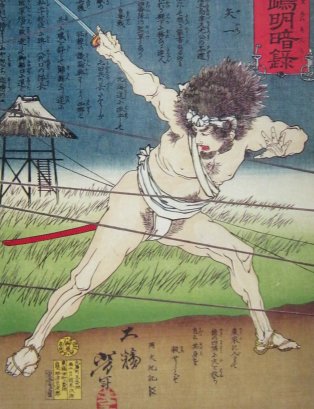

The image to the left is from a Yoshitoshi print. |

|

Funpon |

粉本

ふんぽん |

Copy, sketch or study

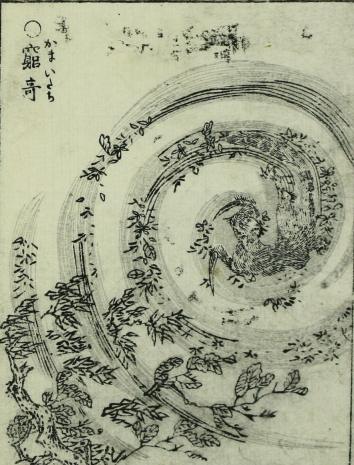

The sketch to the left is from the collection of the National Diet Library. |

|

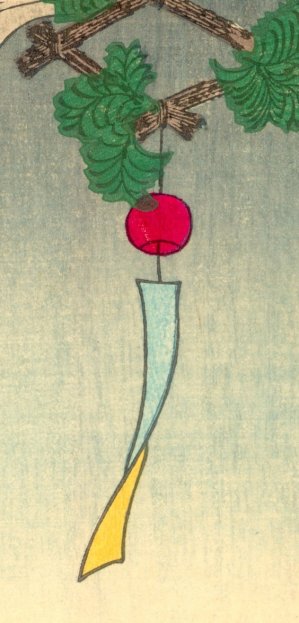

Fūrin |

風鈴

ふうりん |

Wind chimes which are considered a sign of summer. The two kanji characters mean 'wind' 'bell'.

The top example to the left is from a print by Toyokuni III in combination with Hiroshige. The one at the bottom is a detail from a Chikanobu print. Click on the numbers to the right to see the full prints. 1, 2

The Japan Encyclopedia of Louis Frédéric (2005, p. 221) says "Small bronze or porcelain bell to the clapper of which is attached a long strip of paper (tanzaku), bearing a poem or prayer, which flutters in the wind. The clear sound of these bells is said to freshen the air and ward off insects. They are usually hung in tree branches or along the eaves, mainly in summertime." |

|

According to a July 31, 1999 article in the Japan Times by Mami Maruko that by that time there was only one glass fūrin maker left in that country. They often are decorated by painting on the inside of their globes. This is to protect them from the elements which work constantly on the outer surfaces. It takes years to learn how to paint these correctly, often beginning with years of studying calligraphy to get the strokes just right. It can also take decades to learn how to create a globe which will make just the right tinkling sound. "Furin made of metal or copper were first made in Japan during the Muromachi Period. Glass furin spread in the middle of Edo Period, after Chinese artisans taught Japanese the art of glass-blowing in Nagasaki." After World War II the production of this glass product declined precipitously. At that time there were only 8 different makers, but by 1955 there was only one left.

Glass furin with attached tanzaku. Detail of an image posted at Wikimedia by Hunini. |

||

|

|

||

|

Fusuma |

襖 ふすま |

Sliding screen used as a room partition |

|

"Rooms in houses rarely have more than one solid wall.... The other sides are closed off with sliding windows and doors, which move on double runners at the top and the bottom. At the bottom is a groove level with the floor or the mats, at the top a rafter one or two ells below the ceiling so that panels can be opened up and taken away as one pleases."

Quoted from: Kaempfer's Japan: Tokugawa Culture Observed, edited and translated by Beatrice M. Bodart-Bailey, University of Hawaii Press, 1999, p. 263.

U. A. Casal in his "Lore of the Japanese Fan", Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 16, no. 1/2, 1960, p. 82 tells the story of Araki Murashige (荒木村茂) who is summoned for an audience with Oda Nobunaga (織田信長), but suspects that this could be dangerous. In those days "In lordly mansions the sliding doors (fusuma) were not of paper, but of heavy, wooden panels in even heavier frames. They moved in shallow grooves, as the paper fusuma (or karakami) still do. It was just outside of the open fusuma that the vassal had to make his first kowtow which would bring his neck right above the grooves..." Suspecting that this was the moment he feared he whipped out his long metal-based war fan and held it right below his chin. Suddenly the wooden panels were propelled toward his head, but stopped short with a loud noise.

There were similar scenes akin to this loads of movies: Star Wars, Flash Gordon. Not exactly the same, but similar where the walls were closing in until the heroes figured out a way to stop their progress.

Cool as a cucumber Murashige acted as though nothing had happened. Nobunaga was so impressed he forgave him whatever it was that had angered him in the first place. Their detente didn't last forever, but that is another story.

Fusumashōji (襖障子) were opaque sliding panels as opposed to akarishōji (明障子) which are lighter weight and translucent. First employed during the Muromachi period (室町時代: 1392-1568). |

||

|

|

||

|

Futakata |

貳方

ふたかた

|

"Some prints bear an oval seal that reads futakata 貳方. The reason of the meaning beyond this seal is unclear. Futakata literally means "both people" or "both sides" which implies an involvement of two parties. Almost 130 futakata seal were found, the vast majority of which are actor prints. Two-thirds are Utagawa Kunisada (1786-1865), the rest are by Utagawa Toyokuni (1769-1825) apart from one print by Utagawa Kuniyasu (1794-1832), in rare cases the seal can be found on beauty prints such a Kikugawa Eizans (1787-1867) series Fūryū gosekku 風流五節句 and Tōsei meisho gosekku 當世名所五節句 and Ikeda Eisen's (1790-1848) series Fūryū sugata awase 風流姿合. ¶ The earliest found occurrence of futakata is on an actor print related to a performance in the seventh month of 1815; the last relate to performances in the fourth month of 1821. This time period suggests that futakata is somehow related to the closure of the Ichimura Theater between 1815 and 1821. After an unsuccessful show, the Ichimura Theater was closed around the twentieth day of the sixth month of 1815... and reopened on the third day of the eleventh month of 1821... Futakata appears exclusively on prints that were published during this closure period. In most cases, these prints are part of multi-sheet compositions whereas only one sheet composition carries this seal. ¶ However, the appearance of futakata during the closure of the Ichimura Theater could be a mere coincidence, which would explain why a small number of the prints with this seal are not related to kabuki but depict beautiful women. It seems therefore more likely that this seal is related in some way to the censors or the publishers than to the theater. The majority of the prints are published by Uemura Yohei and Matsumura Tatsuemon, the remaining prints are by Tsuruya Kinsuke and four unidentified publishers, several lack a publisher seal at all. A more detailed examination of the datable actor prints reveals that there is a pattern in the release time. The one known print by Tsuruya Kinsuke is from the eighth month of 1815, the 67 prints by Matsumura Tatsuemon were released between the first month of 1816 and the third month of 1819, the 75 prints by Uemura Yohei were issued between the seventh month of 1818 and the third month of 1821. The four unidentified publishers released their prints in the ninth month of 1815, fifth to eleventh month of 1816, eighth month of 1818, and eleventh month of 1818. ¶ In conclusion, during the period of almost six years that futakata was in use, it appears on prints by no more than two publishers at the same time. Futakata apparently points to two publishers that held a specific status. Questions now arise to what this exactly means, who decided why and when a publisher was able to use futakata, and why is futakata not on all the designs that these publishers issued during their time period." Quoted from: Publishers of Japanese Woodblock Prints: A Compendium by Andreas Marks, p. 475.

**** Note that Marks did not appear to source the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston collection of Japanese woodblock prints in the United States. For that reason there are a number of gaps in his stupendous compendium. One such gap is the failure to see that Tsukimaro and Kunimaru both had prints with the futakata seal on them.

To the left is a Kunimaru print with the futakata seal. It is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

|

Futame jigoku |

両婦地獄 ふためじごく |

Two-wives hell: Generally it is represented by a man with two snakes with the heads of women entwined around his body. The jealousy of the first wife has transformed the women into reptilian hybrids. |

|

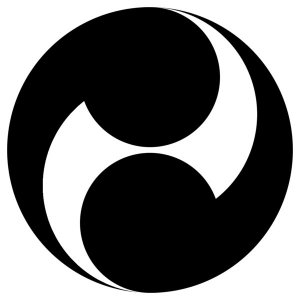

Futatsu-tomoe |

二つ巴

ふたつともえ |

A two-comma tomoe.

According to Mon: The Japanese Family Crest by Kei Kaneda Chappelear (p. 76) it says: "The Tomoe, a comma shaped pattern was first seen in the Asian and European continents in very early times. In China and Korea a white and dark pair joined together represented Yang and Yin - the opposed principles of nature - male-female. ¶ In Japan the design represents a whirlpool in water and implies protection from fire, therefore roofs were decorated with it. ¶ In Heian times the noble family Saionji used it on their carriages. During the Kamakura period the tomoe became the most popular design on garments, household objects, and military items. Later it was made the mon of the Hachiman shrine and thus represented that god of war. The principle families using it were the Utsunomiya, Koyama, and Yuki who were distributed through the entire area north of the Eastern Provinces - the Kantō. It ranked in popularity next to the diamond mon." |

|

Ga |

画

が |

Literally this means picture or drawing, but following a signature it means "drawn by" or "did this picture." Schaap and Uhlenbeck translate this as 'picture of'.

To the left is a 'Kunisada ga' signature from a print from ca. 1811. |

|

Gagō (also called a gō) |

雅号 がご |

An art name. |

|

In the West we have Christian names, surnames, nicknames, noms de plume, stage names, etc., but we have nothing quite like the assortment of names the Japanese have. Not only that but they are often changed and this makes it difficult for a novice to the field to know who is who. "You can't tell the players without a scorecard."

Richard Lane, who actually calls the gō a nom de plume, notes: "Indeed, of the thirty or more alternative names that Hokusai employed during his seventy-year career, about half were passing fancies. Most were used with the previous name for some time, so as not to confuse his public..." Quoted from: Hokusai: Life and Work, published by E. P. Dutton, 1989, p. 23.

It is interesting that a quick search on the term gagō can also mean refined diction or polite expression. Gō by itself means word or language. |

||

|

|

||

|

Gaikotsu |

骸骨

がいこつ |

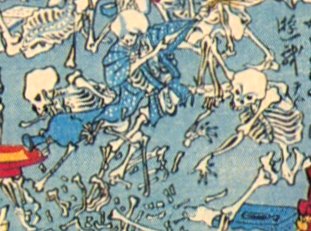

Skeleton(s)

To the left is a detail from a print by Kyōsai.

For much more about skeletons in Japanese art go to our web log at http://printsofjapan.wordpress.com/. Today is June 19, 2010. As of now we have two posts devoted to skeletons, skulls and bones and will be adding a third post soon. |

|

Gama |

蝦蟇

がま |

Toad: In The Animal in Far Eastern Art... by T. Volker it says on page 167 "Besides the hare and the white tiger, gama, the toad is said to inhabit the moon, an idea that originated in ancient Chine. When once it looked as if the clouds would would capture the moon, the Archer-Lord... freed her with his shots. He was rewarded with an elixir of life but his Consort... stole it from it and with it fled to the moon. For punishment she was there changed into a toad." ¶ Demon toads fed on snakes, had poisonous spittle and could bring death to an entire countryside by spitting into the air. However, some had good qualities and could bring rain when it was needed. (Ibid., p. 168)

The Bufo japonicus shown to the left was posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Yasunori Koide.

Toads are also referred to as hikigaeru (蟇蛙) or simply as hiki. |

|

Gama sennin |

蝦蟇仙人

がませんにん |

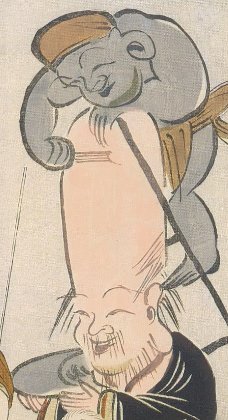

The Toad Hermit: This Taoist tale came to Japan from China. He "...was a seller of magic herbs. He lived in the mountains in company with a giant toad. A legend tells us that when he went bathing he was in the habit of changing into a four-legged toad. A different legend has it that once, he was going to bath [sic] in the river, a certain man... followed him and that Gama sennin gave this person a magic pill that changed him into a toad. Gama sennin feeding a pill to his toad is a frequent image. It is also said that once he found a sick toad, took it home and nursed it back to health. After it regained its health the animal turned out to be a demon, skilled in the magic arts, and instructed his benefactor in the secrets of his science. [He] is depicted as a very ugly fellow without eyelashes and a skin studded with pimples and warts." The toad is always nearby or on him or in some cases he is riding it. (Source and quote from: The Animal in Far Eastern Art... by T. Volker, p. 168)

The image to the left was posted at commoms.wikimedia.org by Tobosha. It is from a painting by Kyōsai. Above is a detail from a Hiroshige print from ca. 1820. The red background is ours.

Gama senin is also called Kō sensei (侯先生). The Chinese version is referred to as Hou Hsien-shêng. |

|

WARNING: Do not be fooled into believing that every figure you see with a toad or toads (or frogs) is Gama senin. One is Tenjiku Tokubei (天竺徳兵衛) who can often be seen astride a gigantic toad. Or, Jiraiya, another fictional character much loved in the early 19th century. |

||

|

|

||

|

Gandō |

龕灯 or 龕燈

がんどう |

A handheld lantern which directs a light very much like a flashlight does. Individually the characters in gandō mean 龕 'alcove for an image' and 灯 'lamp'.

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Ashiyuki. To see the full print and much more info click on this link: |

|

Ganjitsu |

元日 がんじつ |

New Year's Day

Daniel J. McKee wrote: "The first day of the year in the lunar-solar calendar fell sometime between January 21 and February 20 in the modern Julian calendar—the exact date depending on the configuration of the previous year— and was considered to mark the beginning of spring. A year was added to everyone’s age count, figured by the year cycles one had been a part of rather than the day of one’s birth, making New Year also a shared “birthday” of sorts, and therefore a personal—as well as communal, natural and cosmological—“fresh start.” This complex, variable calendar system, originated in China, was officially adopted in Japan in 604, according to an account in the Nihonshoki, and as we will see, was a source for much creativity in the Tokugawa Period (1600-1868). It remained in use until the third day of the twelfth month of the fifth year of Meiji, which officially became January 1, 1873 as the Meiji government made the Julian calendar the new official standard." |

|

Gankō |

雁行

がんこう |

The v-formation of a flight of geese. Often represented in Japanese prints.

To the left is a Hiroshige print from the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Above is a photo posted at Flickr by Alberto_VO5, entitled "Gimme a V." |

|

Ganpi (also gampi) |

雁皮 がんぴ |

A rare type of paper made from the wikstroemia plant 1 |

|

Gassaku |

合作 がっさく |

A single work of art produced by two or more artists, i.e., a collaboration. In the example to the left the figures are by Toyokuni III and the flowers are by Hiroshige. There are many such examples in ukiyo prints and paintings.

There is a very informative and interesting article on this topic by Jan de Jong originally published in "Andon". Below is a link to that article in pdf form. I would encourage everyone to read this.

Separately the kanji characters which make up this term, 合 'join' and 作 'make', form 'cooperation', 'collaboration' or 'coauthorship'.

In an essay, 'Meiji Response to Bunjinga', by Catherine Guth she discusses the aesthetic world around Kido Takayoshi (1833-77): "Calligraphy, painting, and poetry were among the pleasurable pastimes Kido and fellow literati enjoyed at teahouses, often practiced in a state of jovial inebriation. Friends collaborated to create compositions in which the process was as important as the finished product, and individual contributions were subordinated to to the ensemble creation. The crazy-quilt compositions, combining word and image, that resulted from such spontaneous joint efforts, known as gassaku, were valued less for their aesthetic qualities than as confirmations of friendship - something akin to the modern-day group photo." Quote from: Challenging Past And Present: The Metamorphosis of Nineteenth-Century Japanese Art

Professor Leiter in his Historical Dictionary of Japanese Traditional Theatre defines gassaku as "The practice of multiple bunraku or kabuki playwrights collaborating on a play. It may have originated in kabuki in the late 17th century when actor Ichikawa Danjûrô I (writing as Mimasuya Hyôgo) worked with Nakamura Akashiseisaburô. Bunraku does not seem to have used it until late in Chikamatsu Monzaemon's career when he revised other playwrights' work in 1722 and 1723. After his death, puppet plays were increasingly written by hierarchically organized collaborative groups of two or more, and as many as 12 or 13 on rare occasions. Each act was assigned to a separate author. ¶ The results were increasingly complex dramas that permitted a wide diversity of styles and materials. But gassaku also led to a weakening of the relationship between the contents of one act and another and a loss of overall unity." |

|

Ge |

下 げ |

The ge (下) character seen in the lower left marks the second volume of two or the third volume of three, etc.

The images to the left are from the Lyon Collection. Click on them to go to see more information.

|

|

Gehō no hashigozori |

げほうの梯子剃り |

Gehō is another name for Fukurokuju, one of the seven propitious gods. Gehō no hashigozori is the name of the motif of Daikoku shaving the tall -headed Fukurokuju. This was a common image sold at Otsu as a positive and protective amulet. |

|

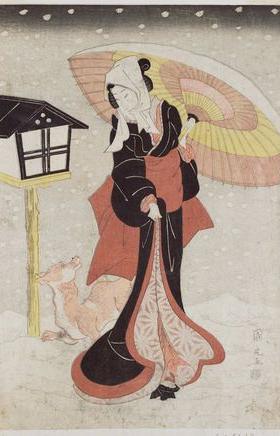

Geisha |

芸者

げいしゃ |

"Geisha means "arts person." As the word implies, it is love of the arts that often prompts contemporay women to become gisha, a lifelong career demanding study of classical dance, the lutelike shamisen, and several singing styles. Unlike most other segments of Japan's entertainment business, the geisha world allows women to work steadily until they become old and gray, for the emphasis is on artistry and conversational virtuosity over looks. Japanese generally respect geisha as preservers of cultural traditons, although some prejudice exists because their love affairs frequently fall outside marriage. Female art-lovers who lack the commitment to become a geisha probably never will glimpse one, however, since their expensive services are almost exclusively aimed at and bought by male politicians and businessmen. Geisha generally do not sell sexual favors, though they used to entertain prostitutes and their guests in the bygone licensed prostitution quarters. Laws in the feudalistic Edo period explicitly prohibited them from offering anything more intimate than art. It is said that a geisha can now earn more than a typical salaried worker on her wages and tips alone, so she is not forced to sell her body as sometimes happened in the past. Still, many do find patrons for a free-flowing exchange of sex, money, and love." Quoted from:Womansword: What Japanese Words Say About Women by Kittredge Cherry, pp. 96-97.

The photo to the left was posted at commons.wikimedia. The original is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

GEISHA WERE NOT PROSTITUTES - except on rare occasions. In the preface to The Story of a Geisha Girl from 1917 the author says: "The European gentlemen who visit Japan generally wish to see the geisha, who are very famous throughout the world as a special class of singing and dancing girls. ¶ Some of the new visitors, however, seem to misunderstand these girls to be equivalent to those in a lower kind of the female professions. If anybody believes them to be so, he is decidedly in a great error; on the contrary, they are a kind of artistes almost indispensable in the society of Japan, if not for ever, at least in the present age. ¶ Of course, there may be some exceptional groups among their circles, who are of low character and in base conduct, just as there are exceptions in all classes of human beings. We do not call them the true geisha girls. ¶ As the women in the geisha calling are generally young girls, they often talk of love, but there are no young women, throughout the upper and lower classes, who do not embrace love in their bosom. ¶ We hope the readers of the book would understand the true features of our geisha girls. "

Up until ca. 1750 all entertainers were male. However, in 1751, a female musician was recorded as having been at a party in the licensed quarter of Kyoto. By ca. 1780 female entertainers had become the norm. |

|

Gempuku (or genpuku) |

元服 げんぷく |

"A coming-of-age ceremony, observed from at least the 7th century through the Edo period (1600-1868), in which a boy assumed adult clothing, hairstyle, and name. The term itself means 'basic clothing.' There was no precise age of the ceremony (in early times it was performed when a boy reached the height of about 136 cm or 4.5 ft.), but it generally fell between the ages of 10 and 16, depending on family convenience. After the ceremony the boy was considered eligible to take on adult responsibilities, participate in religious ceremonies, and marry." Among the court nobility the young man when through the 'cap ceremony' because he could now wear an kammuri. Samurai youths could begin wearing an eboshi and after the 16th century have the front of his head shaved. "A boy of the lower classes might receive a loincloth (funidoshi), in which case the event was called heko-iwai ('loincloth celebration'). In all such ceremonies the boy usually received gifts of adult clothing from either his father or a respected man who was thenceforward considered his patron. In fact, the boy's adult name often incorporated part of the name of the patron..." Source and quote from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 3, p. 17.

Kumon Museum of Children's

Ukiyo-e "The term wakashu derives from olden times when a youth of kuge (nobility) or samurai family, upon becoming an adult, went through a ritual known as gempuku: the ceremonial cutting off of the maegami or forelock. Youths who still wore the maegami were called wakashu." Quoted from: Kabuki Costume by Ruth M. Shaver, p. 38. |

|

Genga |

原画 げんが |

This is the initial sketch, the first thoughts, for what will eventually be transformed into a woodblock print. But that is several stages down the road. "Drawings have served very different purposes for the Japanese and Western artist. In Japan, there has never been any real tradition of drawing purely for the sake of drawing. Students practiced drawing in order to learn it and use it as a preparatory stage in the process of making a painting or woodblock print." (Drawings by Utagawa Kuniyoshi from the collection of the National Museum of Ethnology, Leiden, by Matthi Forrer, 1988, p. 9) The exceptions are the Zenga, Shijō and Nanga schools among others. The first drawing precedes the hanshita which were used to carve the key block. As seen in many surviving examples genga can be very free form only hinting at the finished printed product. Lines may swirling flourishes and calligraphic brushwork which will never appear in the ukiyo print, but which, to my mind, show the true artistry involved in creating. The genga can be 'corrected', 'emended', added to, subtracted from and generally used as a working model. Eventually a more precise drawing will be made from this first form and from this an exact drawing will be worked up for pasting down onto the surface of a woodblock for carving by the master carver. In the process this final drawing is sacrificed to the knife.

Richard Kruml in Ukiyo-e to Shin Hanga: The Art of Japanese Woodblock Prints (p. 31) uses the term gakō (画稿) for genga. "...a preparatory sketch (gakō) had to be drawn using a deer's fur brush and sumi on high-quality mino-gami paper."

PLEASE: If anyone out there has a genga which they could let us reproduce here we would be extremely grateful. Your privacy will be respected. |

|

Genji kuruma |

源氏車 げんじ.くるま |

A decorative pattern of interlocking wheels --- probably of an ox cart which was a traditional means of transportation for the nobility. |

|

Genji monogatari |

源氏物語 げんじ.ものがたり |

"The Tale of Genji" - Japan's first great novel written in the 11th century by Murasaki Shikibu (紫式部). |

|

Genjina |

源氏名 げんじな |

Professional name taken by a prostitute, hostess or geisha. Andrew Gerstle refers to a prostitute's genjina as her poetic name. Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary from the 1931 edition calls this term "the nom de guerre (= professional name) (of a prostitute)." |

|

Genpei |

源平 げんぺい |

A term which means both the Genji and Heike clans or the two opposing sides 1 |

|

Genpei Nunobiki no Taki |

源平布引瀧 げんぺいぬのびきのたき |

Kabuki play: "The Genji and Heike at Nunobiki Waterfall" 1 |

|

Genshoku Ukiyoe Daihyakka Jiten |

原色浮世絵大百科事典

げんしょくうきよえだい ひゃっかじてん |

An 11 volume ukiyo-e encyclopedia.

|

|

In a syllabus for an art history class at Columbia University the Genshoku Ukiyoe Daihyakka Jiten is described as "the single most important and useful reference work in this area." Abundantly illustrated it offers visually more than any other source material on ukiyo-e subject matter that I know of. The text is entirely in Japanese and although my understanding of that language is somewhere to the far side of miserable these volumes still offer me a wealth of information. (Remember: every picture is worth a thousand....) Hours of struggling often end in epiphanies.

Volume 3 alone has been invaluable. At the back of that volume are two lists unlike any others I have seen anywhere: 1) A critical listing of more than 1,000 publishers' seals - far from comprehensive, but better than anything else I have ever seen. Each illustrated entry is accompanied by detailed information about that particular publishing house. And 2) what I believe is the most extensive list of date and censor seals that can be found anywhere.

I am not uncritical of encyclopedias in general whether they are written in English or any other language, but I have to admit that they are almost always the best starting point for a research project. Anyone interested in ukiyo-e who has access to this set should seriously consider spending the time it takes to get to know it well. It is rich and you will surely reap the benefits. |

||

|

LINKS TO OUR OTHER INDEX/GLOSSARY PAGES Click on any of the pages listed below!

|

||

HOME

HOME