JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

Mom thru Nazuna |

|

|

The detail from the diadem of

the Empress Eugénie |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Momijigari, Momoyamajidai, Mon, Monogatari,

Monzenmachi,

Motoyui, Motoyui bako, Mudabori, Muenbotoke, Murasaki, Murasaki bōshi, Murasaki Shikibu, Mushikago, The Mustrard Seed Garden Painting Manual, Mukade, Muken jigoku, Murayama Sakon, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Mushikago, Myōseki, Nabeshima ware, Nadeshiko, Nagabakama, Nagamochi, Nagare kanjō, Nagasaki, Nagasaki-e, Naginata, Nagoya Sanzaburō, Nakamura Daikichi I, Nakamura Fukusuke I, Nakamura Shikan, Nakamura Utaemon III, Nakanochō, Nakazori, Namazu, Nami, Nanushi, Naraka, Nashi, Nazuna

紅葉狩, 桃山時代, 紋, 物語, 門前町,

朦朧体, 本居宣長, 元結, 元結箱, 無駄彫, 無緣仏, 百足, 無間地獄, 紫, 紫牟子, 紫絵, 紫式部, 村山左近, ボストン美術館, 虫籠, 芥子園画伝, 鍋島焼, 撫子, 長袴, 長持, 流灌頂, 長崎, 長崎絵, 投げ頭巾, 薙刀, 名古屋山三郎 (?), 中村大吉, 中村福助, 中村芝翫, 三代中村歌右衛門, 中野町, 中剃り, 鯰, 波, 名主, 那落, 梨, 薺 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

Momijigari |

紅葉狩

もみじがり |

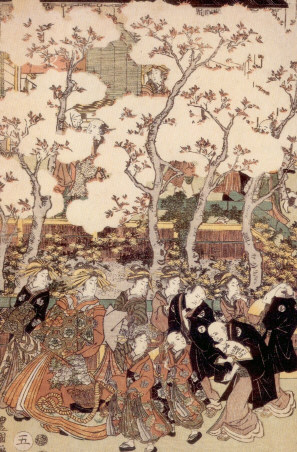

To the left is a detail taken from a Yoshiiku print. While it would appear to be a maple leaf viewing I wouldn't swear to it. This image was sent to us from our generous contributor Eikei (英渓). Thanks Eikei!

Since we started a new post on 10/13/09 on momiji at our new(ish) web log at http://printsofjapan.wordpress.com/ we moved most of our information on this topic to that site.

In Chadō: The Way of Tea : a Japanese Tea Master's Almanac (p. 553) it says: "In days of old there used to be a celebration of red autumn leaves (momiji) in the palace or other places where people had a party surrounded by beautiful wadded-silk garments hung over a line or regular curtains among the maple trees." They would set it up like an alcove, hang a poem written on a fancy strip of paper attached to the branch of the tree, watch the leaves fall around them, drink their tea and compose poetry afterwards. In a poem by Shida Yaba (1662-1740: 志太野坡) wrote:

Viewing the autumn leaves |

|

"The traditional pastime of viewing autumn foliage. Like cherry-blossom viewing (hanami) in the spring, it was popular among the court aristocracy of the Heian period (794-1185). The nobles went boating on ponds in teh gardens around their mansions, playing music and composing poetry while viewing teh fall colors, or went on excursions into the mountains to gather brightly colored leaves. From the twelfth to sixteenth centuries the Tatsutagawa area near Nara and the Ogurayama and Arashiyama areas near Kyōto, famed for their autumn leaves, were described in numerous poems and paintings. In the Edo period (1600-1868), the custom spread among the common people. With the improvement of public transportation after the Meiji period (1868-1912), people began to visit distant places noted for their beautiful foliage, as well as nearby places, and the tradition continues to this day." Quoted from the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 5, p. 236.

"Unlike cherry-blossom viewing parties in the spring, which include drinking, eating, singing and dancing, koyo or momiji-gari is much more sedate. Families, friends and small groups go into mountain forests that are only a short drive or train-trip from any town or city in the country, and simple walk among the trees, admiring the beauty of the colorful leaves and enjoying the serenity of the woods. ¶ Many foliage viewers take picnic lunches, find some especially scenic spot, and wile away an afternoon absorbing the ambiance. Both momiji and koyo mean the crimson color of leaves in the fall, but they generally refer to maple and ginko trees." Quoted from: Exotic Japan! The Visual and Sensual Pleasures by Boyé Layfayette De Mente, pp. 137-138

By parsing the kanji for momijigari 紅葉狩 we come up with 紅葉 for autumn colors and 狩 for hunting.

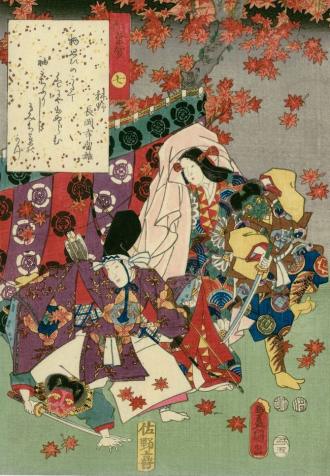

There is a noh play called Momijigari. "Another noh play from the same time period, Momijigari (attributed to Kanze Nobumitsu [1435-1516]), presents demons in the disguise of beautiful upper-class women on an outing to view fall foliage. Taira no Koremori is wined and entertained by them and falls asleep, drunk. The demon/woman leaves him in order to undergo transformation, but upon leaving him, she says, 'Dozing while waiting for the moonrise, the dew upon the singly laid sleeve is deep; do not awaken from your dream'.... A deity appers in Koremori's dream to warn him of the true identity of the women, and he succeeds in defeating the demons in a battle." Quoted from: Writing Margins: The Textual Construction of Gender in Heian and Kamakura Japan by Terry Kawashima, footnote #127, p. 285.

based on the noh play

In Traditional Japanese Theater: An Anthology of Plays edited by Karen Brazell on page 22 it translates Momijigari as "Hunting for autumn leaves". In Zeami's Style: The Noh Plays of Zeami Motokiyo by Thomas B. Hare it is translated as "Gathering Maple Leaves" on p. 240.

One if not the first theatrical productions captured on film was Momiji-gari in 1899, but not released until 1903. Source: Japanese Classical Theater in Films by Keiko I. McDonald, p. 38. |

||

|

|

||

|

Momoyamajidai |

桃山時代 ももやまじだい |

Momoyama period (1583-1602) |

|

Mon |

紋

もん |

A family crest or coat of arms. Other terms used for such crests are jomon (定紋) and kamon (家紋) 1, 2

In 1668 a law was promulgated which, among other things, prohibited the display of family crests on the sliding doors of newly built residences in Edo belonging to the hatamoto (旗本), i.e, the samurai in the direct employ of the shogun. But it wasn't just the hatamoto who were affected. So were the townspeople: "Lacquering such parts as the front sill of the tokonoma and frames [of doors and windows], and affixing family crests to sliding screens are forbidden. Note: there should be no decorative gold and silver crests or paintings inside the main room [zashiki 座敷]."

Souce and quote: "Edo Architecture and Tokugawa Law", by William H. Coaldrake, Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 36, No. 3. (Autumn, 1981), footnote 13, pp. 270-2. |

|

By the 19th century only certain daimyo were allowed to affix their family crests to their front gate. (p.274)

These rules are actually not so surprising since there seem to have been edicts governing every aspect of life. However, such restrictions were only as good as the power behind them. Hence, many were basically ignored. I can't vouch for this one.

According to footnote 3 in Donald Shively's article 'Sumptuary Regulation and Status in Early Tokugawa Japan’ published in the Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 25, (1964 - 1965), p. 159 - if I am understanding it correctly - it was standard practice to apply the family crest in five places on the kosode and that this is still the custom today. Shively cites Seiroku Noma as his source.

The two element of the kanji for mon (紋) separately mean 'thread' (糸) plus 'text' (文). The first crest designs used by the Imperial court were probably borrowed from the Chinese. However, during the Heian period (794-1185) Japanese nature motifs became more popular throughout the aristocracy.

"Family crests, however, were not the only type of mon. Mon were also used by Shintō shrines, with this type of usage dating back to the Kamakura period (1185–1333). These mon are called shinmon (神紋). The types of designs used for these mon were similar to those used by families. Shrines would sometimes adopt the mon of a patron family, and conversely a samurai might adopt the mon of a shrine he had a close connection to. Mon could also move between shrines, such as when an enshrined kami (Shintō deity) was transferred. Buddhist temples also used mon in a similar way. Such mon are called jimon(寺紋)." Quoted from: O-umajirushi: A 17th-Century Compendium of Samurai Heraldry, p. xxii.

"Despite the widespread use of mon, they focused on a relatively fixed set of motifs, generally varying an existing motif rather than creating something totally different. Mon based on stylized depictions of plants were most common. Abstract geometric designs were also very popular, as were designs based on Japanese characters. Birds and butterflies were sometimes used, but other types of animals were uncommon, and human figures were very rare." Ibid.

"In modern Japan, mon are thought of as being monochrome designs that have no particular color. At the time of O-umajirushi, however, color was often an important part of a samurai's heraldry. Banners were generally depicted with consistent colors, most commonly the five “lucky” colors: blue, yellow, red, white, and black. Different color combinations might be used to distinguish different members of a family or different families that used the same mon, so these distinctions were important. In some cases, the banner color seems to be more notable than the mon itself; for example, the troops of Doi no Ōi-no-kami were known for their yellow banners, not for the water wheel mon on them. This makes sense, because on a hectic battlefield, banner color is easier to distinguish from a distance than mon design. Different units might be distinguished by different characters or colored bands on a consistently-colored flags. Conversely, in some cases a samurai commanding many units would give each unit a flag with a different background color but a consistent mon. In addition, a samurai might still use his mon with different colors in other situations, such as marking personal possessions or on clothing, where another design aesthetic might take precedence and identification from a distance was not important. Thus, the color was not always an inseparable characteristic of the mon." Ibid., pp. 24-25.

The first mon appeared during the Nara period (710-794) and were used by the aristocracy. The chrysanthemum mon did not become exclusive to the Imperial family until the 13th century. The samurai began to use mons during the Gempei wars in the 12th century. During the Edo period lower classes began to use them. Merchants adopted their use during the Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573-1603) and later it was used by actors and prostitutes.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Monogatari |

物語 ものがたり |

A story, tale or legend as in the Heike Monogatari (平家物語) or the Genji Monogatari (源氏物語). |

|

Monzenmachi |

門前町

もんぜんまち |

A town which was originally built around a temple or shrine. In 1950 it was calculated that only 6% of all Japanese cities had been monzenmachi. (Source: Modern Japanese Society, Part 5, Volume 9, p. 282)

|

|

|

もり蕎麦 もりそば |

Soba noodles served cold on a bamboo rack or mat inside a lacquer box. Accompanied by a bowl of broth and chopped green onions and wasabi. Very popular.

Donald Ritchie wrote in A Taste of Customs and Etiquette in Japan on page 59 and 61: "The menuri [i.e. noodles] connoisseur knows a lot. He knows, for example, that cold soba is eaten with very little dipping broth, the less the more elegant. And, if he is a true aficionado, he knows the reason. In seventeenth-century Edo, during the period when menuri were becoming popular, it was deemed countrified to drown the noodles in the sauce. The result was that cold soba is , in the proper establishment, now served drained on flat bamboo baskets and a small amount of sauce is flavored and reserved for some dipping, if at all. In this way the connoisseur may savor the taste of the noodles themselves, flavor undiluted by the excess of sauce." |

|

Mōrōtai |

朦朧体

もうろうたい |

Hazy style of painting - This style uses shading rather than tradition line work to define the imagery.

To the left is a painting of ink on silk by Yokoyama Taikan (横山大観: 1868-1958). It is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

|

Motoori Norinaga |

本居宣長

もとおりのりなが |

Classic scholar of the Edo period 1730-1801. Genchi Katō (玄智.加藤: 1873-1965) said that "...Norinaga [was] one of the greatest scholars of the Restored, or Pure Shinto, who is famous for having rejected the two doctrines respectively of Chinese Philosophy and of Buddhism." Katō also noted the respect the Tokugawa shogunate had for Chinese philosophers. "As a result, the time-honoured tendency to unite Shinto with Buddhism was checked and insistence was given to the uniting of Shinto with Confucian philosophy, Shinto thus being separated from Buddhism and brought into harmony with the Chinese Wisdom." But since neither Buddhism nor Confucianism were indigenous to Japan people like Norinaga rejected both and wanted to sever all links: "...he was both anti-Buddhist and anti-Confucianist". For this Norinaga was considered one of the "Four Great Nationalist Scholars." ¶ Norinaga studied and wrote about the Kojiki since it was unadulterated by foreign sources. (Source and quotes: The Shinto Studies of Jiun, the Buddhist Priest and Moto-ori, the Shinto Savant by Genchi Katō, Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 1, No. 2, (Jul., 1938), pp. 301-316) |

|

Motoyui |

元結 もとゆい |

Cord for tying hair - usually made of paper. In many cases these may be decorative touches, too. This item has an ancient traditon. Taira Kanemori (平兼盛: ? - 990), one of the 36 Immortal Poets, wrote:

The autumn drawing as a momento, a thin layer of white frost on the cord that binds my hair.

Quoted from: Currents in Japanese Culture, edited by Amy Vladeck Heinrich, p. 477.

From the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Motoyui are mentioned

twice in poems at the end of the first chapter the Tale of Genji.

|

|

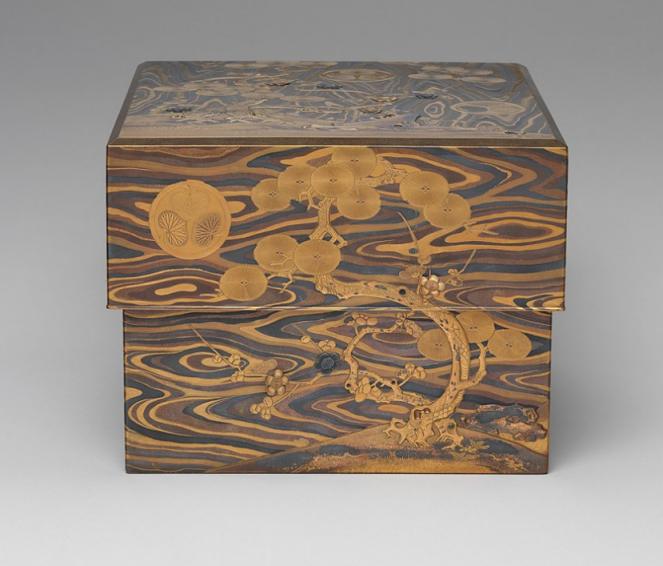

Motoyui bako |

元結箱

もとゆいばこ |

A box used for hair ornaments.

The image to the left was found at Wikimedia.commons. It is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It has the Tokugawa family crest on it and dates from the early 18th century. |

|

Mudabori |

無駄彫 むだぼり |

Unnecessary or useless carving: "...as its meaning implies, [mudabori] is a part of the cutting work which must be done in the finest detail, but when it is later transferred to its respective colour block, it is scraped off the key-block as being superfluous or unnecessary..."

Quoted from: "Ukiyoe: Some Aspects of Japanese Classical Picture Prints", by Shigeyoshi Mihara, Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 6, No. 1/2, 1943, p. 260.

There is another reference to this term in our entry on sengaki. |

|

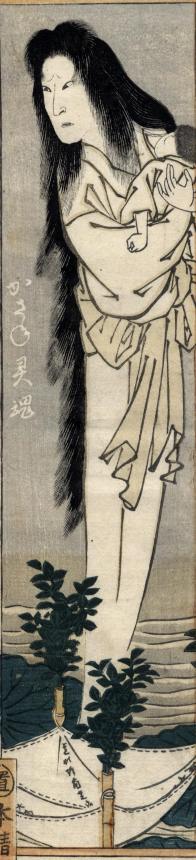

Muenbotoke |

無緣仏 むえんぼとけ |

Mary Picone describes muenbotoke as 'errant souls'. William Hare Newell in his book Ancestors defines them as "...those ancestors to whom descendants owe no direct 'relationship'..." Their spirits are "excluded" and so are viewed as 'defective'. However, they are still worshipped by the household tenuously tied to them. Newell also noted that Yanagita Kunio wrote in 1926 "...that ancestors in Japan are variably beneficent to their direct descendants." But since then there has been a lot of rethinking of this belief. ¶ Another category which can be distinguished from that of the muenbotoke is the gakki or 'wandering souls'. "While gakki can be harmful, muenbotoke are not." Ancestral, household souls which are worshipped are referred to as hotoke. However, when their lineage comes to an end they change from hotoke to muenbotoke, but that is a transition that can never happen for gakki." [Gaki (餓鬼) - one 'k' - is defined as a hungry ghost or famished devil. It can also be a brat or imp.] Once a household comes to an end its associated spirits are disenfranchised, so to speak, and can move from benign spirits to malevolent ones. ¶ Another category or muenbotoke are deceased children. "The general impression is... that the status of the muentoboke is unchangeable and intrinsically linked with the position they had, while still alive, in the ie [or household]." Theirs is a 'miserable state' and Newell also describes it as "...indeed the least enjoyable state in the world beyond." Newell also noted that "From the range of anomalous events, natural calamities are not ascribed to the ancestors nor to the muenbotoke as punishment from a wrathful god. For this reason the villagers will not address themselves to their ancestors for protection against drought, or flood, or earthquakes." ¶ A divorced woman who returns to her original home and who doesn't remarry does not have a chance of avoiding becoming a muenbotoke. |

|

Mukade |

百足 むかで |

Centipede - a creature which has both negative and positive connotations in Japan traditionally. It is used to represent Bishamon, one of the seven propitious gods. Other than that the centipede seems to be viewed negatively.

|

|

Laurence Bush in the Asian Horror Encyclopedia says of the centipede: "Strangely enough this normally tiny creature is an enormous monster in Japanese monstrology. One mountain-sized specimen lived in the mountains near Lake Biwa where it was slain by the hero Hidesato. The grateful Dragon King rewarded him with a bag of rice that never emptied." (p. 29)

Edward Sylvester Morse (エドワード・シルヴェスター・モース: 1838-1925) an important American visitor to Japan in the late 19th century records a visit to a village during a typhoon. He was searching for ancient pot shards and shells. The villagers told him that they had discovered a hole in the ground that appeared to be a long-forgotten burial site. Morse wanted to see it despite the weather conditions. When they got to the hole two strong fellows lowered him into the hole. But when he dropped down he was waste high in water and it was almost pitch black. He yelled up to his assistant that he was all right "...when in agitated tones he told me that great poisonous centipedes were crawling out fo the opening! I had on my wide-brimmed hat and a slippery rubber coat, and what I had supposed to be crumbs of earth and pebbles tumbling from the sides of the ragged hole were huge centipedes dropping on me! I stood literally in a cascade of venemous creatures." Quoted from: The Great Wave by Christoper Benfey, pp. 46-47. |

||

|

|

||

|

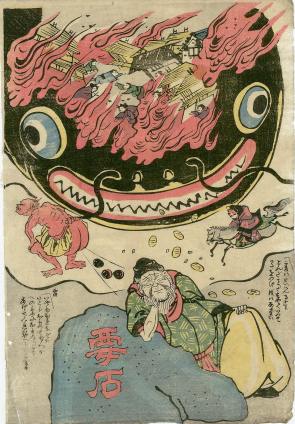

Muken jigoku |

無間地獄 むけんじごく |

"...the deepest and worst of the eight burning hells, where evildoers are tortured constantly without intermission."

Parsing the kanji of this term one could come up with 無 meaning 'nothingness', 間 'space', 地 'earth' and 獄 'prison'. |

|

The Avici Hell of traditional Buddhism. This is a place where sufferers are kept in flames continually, but are neve consumed. The Tāpana Hell, the 6th worst, which is filled with flames is reserved for those who have "...roasted or baked animals for their food."

"Two of Jizō's four previous lives, as described in the Sutra of the Past Vows, were as a woman, which is extremely unusual for a prominent deity. In one life, Jizo was the devout daughter of a faithless brahmin woman. The mother died and fell into the worst hell of all, the Uninterrupted Hell (Muken jigoku). Distraught, the daughter made offerings to a buddha image and prayed to have the details of her mother's rebirth revealed to her. While gazing at the image, she heard a voice identifying itself as the statue inform her that she would soon see her mother. ¶ The daughter then fell into hell herself, where she was told that because of her meritorious actions, her mother had already been reborn in one of the heavens. Everyone else in hell was also saved. Rejoicing, the daughter vowed before the buddha to save any living beings who were suffering in hell because of their past evil deeds." Quoted from: Living Buddhist statues in early medieval and modern Japan by Sarah J. Horton, p. 140.

According to Eihei Dōgen: Mystical Realist (p. 220) Dōgen (道元: 1200-1253), the founder of Sōtō Buddhism, believed that we reap what we sow. "He said that those who committed the five cardinal sins (killing a father, killing a mother, killing an arahat, injuring the body of Śākyamuni Buddha, and destroying the Buddhist order) would be sent to the avīci hell (muken-jigoku or abi-jigoku) immediately after their death, where they would endure incessant suffering and torture."

For those who slander the Lotus Sutra: "When his life comes to an end he will enter the Avichi hell, be confined there for a whole kalpa, and when the kalpa ends, be born there again. He will keep repeating this cycle for a countless number of kalpas. Though he may emerge from hell, he will fall into the realm of beasts, becoming a dog or jackal, his form lean and scruffy, dark, discoloured, with scabs and sores, something for men to make sport of." Quoted from: Augustine and World Religions, p. 182.

In The Record of Linji (p. 177) there is a translation of one of the horrific tortures of this level of hell: "[The warders of hell,] having pried open. [the victim's] mouth with tongs, pour into it molten copper. They force him to to swallow red-hot iron balls that on entering the mouth scorch the mouth, on entering the throat scorch the throat, on entering the belly, and, when the five vital organs have been completely charred, immediately pass out and fall to the ground."

There was a bell when struck would bring wealth in this world in exchange for eternal suffering in Muken jigoku and extreme poverty for one's descendants.

Nichiren damned all Buddhists who failed to put their faith in the Lotus Sutra. "He is also known for his vociferous denunciations of other Buddhist schools of his day, including the following oft-cited passage: 'The nembutsu [recitation of the name of Buddha] is Avīci hell, Zen the devil, Shingon national ignorance, and the Vinaya piracy.' He blamed the spate of natural disasters, starvation, and plagues that befell the archipelago on local Buddhism's straying from the true teaching contained the Lotus-sūtra." Quoted from: The "Shomangyo-gisho" of Shotoku Taishi... by Mark Dennis, fn. 226, p. 108.

In The Letters of Nichiren, published in 1996, there is a choice passage which sums up his view of humanity: "Not a single person will be able to escape from the sufferings of birth and death, and in the end they will all become slanderers of the Law. Those who, because of slandering the Law, fall into the Avici Hell, will be more numerous than the dust particles of the earth, while those who, by embracing the Law, are freed from the sufferings of birth and death, will amount to less than the quantity of soil that can be placed on top of a fingernail."

Junichiro Tanizaki (谷崎潤一郎: 1886-1965) wrote a short story called The Two Acolytes. One was more a sinner, the other more a saint. "And when he did manage to close his eyes, images of women of every kind floated before him so vividly that his whole night's sleep was disturbed. At times they appeared as buddhas with the thirty-two signs of sanctity and seemed to embrace him in a purple golden radiance; at others, they took the form of demons from the Avici Hell about to burn him up with tongues of flame that blazed from the tips of their eighteen horns." |

||

|

|

||

|

Murasaki |

紫

むらさき |

Murasaki or shikon (しこん): A fugitive purple dye which often fades to gray. Like so many other dyes this one is fascinating if only for the discovery of its original properties. The leaves are green and the flowers are white, but the roots...the roots are another story and the source of this colorant. Some sources say it is native to Japan while others say that it was the Chinese who first used its dyes.

The cell color to the left and below is murasaki purple.

Don't forget that color descriptions are not exact. As there are many shades of green or blue for example, there are many slight variations within each of the colors shown here which may or may not conform precisely to your own perceptions of what they should be. |

|

According to Amanda Mayer Stinchecum in Kosode: 16th-19th Century Textiles from the Nomura Collection: 16th-19th Century Textiles from the Nomura Collection (pp. 202-3) the Lithospermum erythrorhizon is a perennial plant which grows in mountains and fields to 30 to 60 cm. The roots were "...harvested in the fall, dried and stored for several months before use." These contain shikonin which is a naphthaquinone derivative. For optimum effect the plant should be at least three to four years old.

Ideally the roots should be soaked and pounded in 60° water in winter. The intensity of the dye ranges from a keshi murasaki or lilac gray to a waka murasaki or light purple to kōki murasaki or dark purple. The color when used for fabrics will deepen when stored away from light for up to one year.

In England this plant is known as the gromwell.

The photo of the murasaki flowers to the left was sent to us by Shu Suehiro. It was taken on May 29, 2004 at the Uji Botanical Garden (宇治市植物公園) in Kyōto prefecture. According to Shu it is difficult to find this plant in the wild.

Shu runs a wonderful Japanese botanical web site. We would urge you to visit it at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. |

||

|

|

||

|

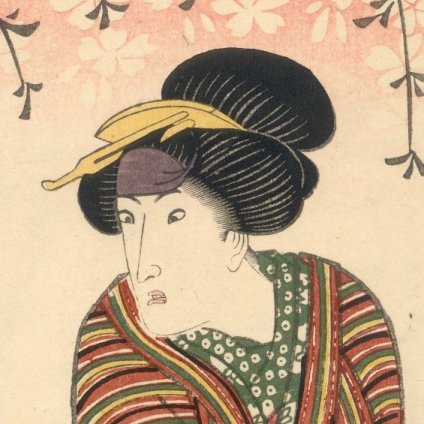

Murasaki bōshi |

紫牟子

むらさきぼうし |

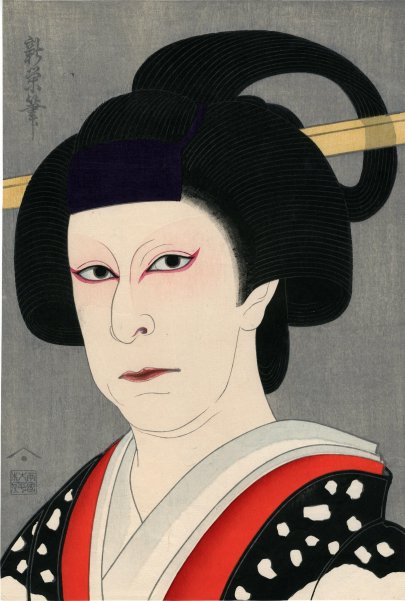

A silk cloth worn by an onnagata at the top of the forehead where the shaved forelocks would have been. Often the cloth is purple, but not always. Cautionary note: Not all onnagata are portrayed on prints wearing this cloth. 1

The image shown above is of a Shun'ei print from the Lyon Collecction. Below is a detail from that print.

|

|

Professor Leiter has an informative entry on the murasaki bōshi in his New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of kabuki jiten (p. 423). He translates it literally as 'purple headgear'. According to Leiter Torii Shōshichi was the first onnagata to wear this in the 17th century. "Although boshi now means a hat, it did not when this term was coined." Originally this attachment to the wig was worn during special ceremonies ostensibly to keep dust of the actor's forelock. However, after they were forced to shave that part of their hair handsome young actors began wearing "...a fashionable man's silk band (yarō bōshi) on their heads in order to maintain their physical attractiveness. This proved effective as it not only made the actor's face seem smaller, but introduced a nice variation between the whit skin and the black hair."

Gary Leupp discusses the forced cutting of the forelocks of kabuki actors in his Male Colors: The Construction of Homosexuality in Tokugawa Japan (University of California Press, 1997) "By denying youth - and female-role actors this adornment, the authorities intended, according to the Tōkaidō meishoki, 'to make them unsightly to look at,' and for a time, indeed, the shaven-crowned actors proved a turnoff for Tokugawa audiences. The Edo meishoki says they looked 'like cats with their ears cut off.' Even so, 'it seems later they were not thought so ugly.' " (p. 131) Later Leupp adds that "Actors were obliged to maintain these shaven pates and at times even had to report to an inspector, who would insure that their forelocks were less than a half-inch long. Forbidden to use wigs, they soon hit upon the device of placing purple scarves over their foreheads; officials permitted this, presumably because they found the effect suitably unerotic, but (testifying to the malleability of the libido) the purple scarf itself soon assumed erotic connotations." (p. 132)

According to Kabuki: A Pocket Guide by Ronald Cavaye and Tomoko Ogawa (Tuttle Publishing, 1993, p. 82) the purple cloth was also called a katsura. A gray cloth would be employed for the role of an old woman.

Above is a detail from a photo of the purplish-red leaves of the katsura (桂) tree in a Belgian park in the springtime. This was taken by Jean-Pol Grandmont and was placed at Commons Wikimedia. Surely this is what gives the murasaki bōshi its other name. To see the full, beautiful image go to the site linked above.

Samuel Leiter in his New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of kabuki jiten (1997 edition, p. 281) addresses the issue of forelocks and katsura - and just about everything else. "Ever since the Kamakura period (1185-1333), Japanese men have borrowed the warrior's custom of shaving their crowns (sakayaki), a practice first begun to keep heads relatively cool under heavy helmets. Only boys continued to wear hair on their crowns. This hair, worn as a forelock (maegami), was considered physically alluring, especially to homosexual spectators. It would have to be ceremoniously removed when a boy reached his maturity at sixteen. In yaro kabuki the forelock-less actors were forced to rely on performing skills rather than beauty to attract audiences." |

||

|

|

||

|

Murasaki-e |

紫絵

むらさきえ |

A category of pictures in which purple was used extensively while the use of red was avoided.

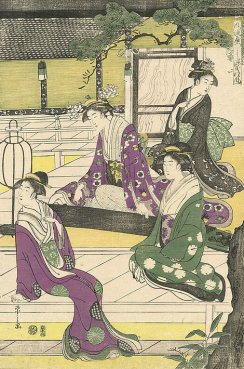

The image to the left is by Eishi and was sent to us by a very generous contributor. Thanks! |

|

Murasaki Shikibu |

紫式部 むらさきしきぶ |

The author of The Tale of Genji. Mildred Tahara gives her dates as ca. 979 - 1016. |

|

This 11th century masterpiece by Lady Murasaki (ca. 973-1014) is considered by many sources to the first great novel written anywhere. Not only that it has remained an adored classic among the Japanese through the centuries and has infiltrated many of the various layers of the culture.

Almost nothing is known about the life of this author. She is believed to have died in ca. 1014. She was born into a family which had turned increasingly to literary pursuits. Even though the study of Chinese poetry was mainly a masculine domain she showed a precocious ability in this field. In 999 she was married to Fujiwara Nobutaka who was many years her senior. Two years later she was a widow. In 1006 or 1007 she entered the service of one of the major consorts of the emperor Ichijō. There she was surrounded by witty and brilliant talents who must have stimulated her latent abilities. Source: The Princeton Companion to Classical Japanese Literature, by Earl Miner, Hiroko Odagiri and Robert E. Morrell, 1985, p. 202.

Even the name, Murasaki Shikibu, is somewhat shrouded in mystery. "She seems to have been known during her lifetime as Tō no Shikibu... Tō, the Sino-Japanese reading for the character fuji or 'wisteria,' clearly designates the Fujiwara family, to a cadet branch of which she was born. Shikibu refers to the Shikibushō or Ministry of Rites, in which both her father and brother held office.

Two theories have been advanced to explain the Murasaki element: that because it means 'purple' it refers to the wisteria of her family name; and that it derives from the name of Genji's great love in the Genji monogatari." Note that very few names of women from that period are known to us today. Source and quote from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan entry by Edward G. Seidensticker (vol. 5, p. 267).

"Some twelfth-century readers believed that Murasaki Shikibu must have gone to hell for concocting such a tale." Quoted from: Encyclopedia of Erotic Literature, p. 932.

At the end of the nō play Genji kuyō Lady Murasaki is revealed to be the Kannon, Goddess of Mercy. |

||

|

|

||

|

Murayama Sakon |

村山左近 むらやま.さこん |

According to Ruth Shaver in her Kabuki Costume on page 38 says that Maruyama Sakon was the first true onnagata. Even though Nagoya Sanzaburō was the first man to dress in women's clothes in this art form it was Sakon who changed the theater forever. "Undoubtedly to offset the inevitable boredom of all-male casts, the role of the onnagata - the female impersonator - the ultimate in Kabuki allurement, was born. Maruyama Sakon is credited with being the original onnagata of an all-male troupe, though Nagoya Sanza previously had appeared in female dress. Sakon first appeared as a woman in Kyoto in 1649. Later he brought his act to Edo, where he danced at the Murayama-za, a theater owned by his elder brother, Maruyama Matasaburō. Sakon's innovation was enthusiastically accepted and became so popular that he soon had onnagata rivals, among whom the most highly acclaimed during the next form of Kabuki, known as Yarō Kabuki, were Ukon Genzaemon, Nakamura Kazuma, and Kokan Tarōji."

Shaver goes on to say that we do not know much about Sakon's costumes. "It is known only that he wore a silk kimono and a beautifully colored oblong silk cloth over his partially shaven head and that he used cloths of different colors for various roles. It can be assumed that he used female make-up." (Ibid., p. 39)

|

|

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston |

ボストン美術館

|

Hugo Munsterberg wrote: "Because of this great interest and enthusiasm for Japanese prints, important collections of them were formed in both Europe and America long before Japan itself became aware of their aesthetic and historical significance. The most outstanding public collection was that at the Boston Museum, which acquired 10,000 prints from Fenollosa and is to this day the best and most extensive collection of ukiyo-e in the world. Other fine collections were formed in London at the British. Museum which in 1906 acquired the collection of Arthur Morrison, consisting of no fewer than 1,851 prints, as well as in Paris, Berlin, Hamburg, and Dresden. There were also numerous private collections, notably in Paris, among which. the Vever Collection was probably the most illustrious."

The image to the left comes from this museum's web site. |

|

Mushikago |

虫籠 むしかご |

Insect cage

The image to the left is a detail from a print in the Lyon Collection. Click on it to see more information. Below is a photo posted at commons.wikimedia by Mitsu yome.

|

|

The Mustard Seed Garden Painting Manual

|

芥子園画伝

かいしえんがでん

|

There was very little cultural contact with China in the 18th century. That is why the publication in 1753 of "The Mustard Seed Garden Painting Manual" hit the Japanese marketplace with such a bang. There was a thirst among many Japanese artists for a clear understanding of Chinese painting. "It offered age-old principles, practical advice, dozens of actual pictures, and a might dose of encouragement.... it quickly became the philosophical bible of a new generation of painters who were already looking to China for inspiration and example."

I am mentioning this for two particular reasons: "Here is the first use of wood grain [ita-mokuhan] as a pattern, the first use of gradation printings [bokashi], the first use in prints of contrast of texture and color saturation: the result is printed textures that look like colored acquatint."

Source and quotes: Ehon: The Artist and the Book in Japan published by the New York Public Library and the University of Washington Press, 2006, p. 82.

A cultural phenomenon: Decades ago a great scholar told me that "The Mustard Seed Garden Painting Manual" was far more popular in Japan than it ever was in China. It first appeared there in 1679.

Like so many other ehon this was published in several volumes over several years - not to mention later editions. The examples to the left originally appeared in 1748. However, these probably are from a later date, but still from the original blocks. At our request our great contributor E. sent us this bird and flower page. Thanks E!

The detail of the pomegranate gives a sense of the care used to translate the Chinese version into a marketable Japanese commodity. |

|

Myōseki |

名跡

みょうせき |

Most translations of myōseki as 'family name' do not even come close to the true usage of this term. In the West we have a number of practices that hardly exist in the East: kings and queens, the nobility, popes and even certain families are in the habit of naming new members after previous ones. The popes are the only ones among this grouping who rarely if ever have any blood relationship to their predecessors - unlike certain earlier periods - but who adopt their names all the same - of course, with the addition of the next sequential number. |

|

In Japan there is a different practice: In sumō, the theater, and among courtesans it is considered an honor to have the name of a famous predecessor bestowed upon you. In the case of kabuki it often involved the adoption of an young trainee who lived up to expectations. In the arts Hiroshige I is followed by his adopted son, Hiroshige II, who also married the master's daughter. Toyokuni II was the son-in-law of Toyokuni I.

The same succession lines were true of famous courtesans who were renowned for their beauty and their skills both on and off the mattress. Courtesans had only a few short years to reach the top, burn brightly and then dim only to be replaced by younger, more supple women. If a truly famous courtesan of one house attained a reputation comparable to that of another famous earlier beauty of that house the new one might be allowed to use the name of her predecessor.

If we practiced this in the West there probably would have been a Marilyn Monroe (マリリンモンロー) II or III, several Rembrandts or even have been cursed by a Beethoven (ベートーヴェン) V or VI by now. Thank goodness we haven't. Let's leave that custom to the Japanese who seem to do quite well with it - but not always.

One more note - and I am not absolutely positive about this - but the Jews never name children after their parents directly either for religious or superstitious reasons. I add that only because of the great variances between different cultures. All of this fascinates me.

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Eizan from the 1830s. It shows the courtesan Hanamurasaki. Cecilia Segawa Seigle in her Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan (pp. 127 and 128) noted: "Thus the last of the legitimate tayū was Hanamurasaki, whose name disappears after the New Year 1761..." Later she added: "One notes that the names Hanamurasaki and Komurasaki were immediately transformed into succession names of the lower-rank sancha in 1762 at the Corner Tamaya. Yet the hallowed tayū name Takao was never again used at any house after 1761. |

||

|

|

||

|

Nabeshima ware |

鍋島焼

なべしまやき |

"...(nabeshima-yaki). Porcelain ware. Blue and white, celadon, and polychrome porcelains, mainly for table use, made in or near Arita, Hizen Province (now Saga Prefecture), Kyūshū, from 1628 to 1871. The Iwayagawachi kiln (1628-61) produced underglaze blue and white ware that was not of the highest quality. The Nagawara kilns (1661-75) made excellent blue and white and polychrome pieces. Both kilns were patronized by the local daimyō. On a larger scale, the Nabeshima daimyō, lords of the Hizen domain, operated a kiln for their own exclusive needs at Ōkawachi from 1675 to 1871; the finest work, of a technical perfection unrivaled by other Edo period (1600-1868) porcelain, was done in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, with a subsequent decline in quality most marked after 1804. ¶ Nabeshima ware production was closely supervised, technical secrets were carefully guarded, and defective pieces were destroyed. At Ōkawachi, bodies were made and fired and transfer technique designs executed; overglaze polychorme pigments were applied and fired by a small number of artisan families in Arita. Among the carefully and uniformly potted pieces, dishes were most common, in four standard sizes with a characteristic high foot with a comb design. Less common were sake and food cups and least frequent were jars, flower vases, water containers, and incense burners. ¶ Nabeshima designs - the most inventive, varied, striking, and asymmetrical among Japanese porcelains - were outlined in soft, pale, dull underglaze blue or, if polychrome, finished in strong, transparent, thinly applied red, yellow, and bluish green overglaze enamels. They mainly comprised flowers, shrubs, leaves, fruits, and vegetables, at times treated with considerable abstraction or else in textile patterns. After 1696, designs with a central white area as derived from Imari porcelains... became characteristic, with the backs of dishes having underglaze blue decoration, usually peonies, chrysanthemums, scrolls, or jewels bound with ribbons. ¶ Starting with Soeda Kizaemon (d. 1654), the kilns were managed for many generations by the Soeda family and pigments were prepared by the Imaizumi family in Arita. Imaemon XII (1897-1975) and his son Imaemon XIII (b. 1926) have carried on the family traditions at a high technical level." Quoted from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, volume 5, p. 299. The entry is by Frederick Baekeland.

The image to the left is from the Kyūshū Ceramic Museum. It was posted at Wikimedia.common and is credited to Georges Le Gars. It is dated ca. 1690-1710s. |

|

Nadeshiko |

撫子

なでしこ |

Dianthus or pink - one of the Seven Flowers of Autumn - The archaic meaning is a caressable girl or as Haruo Shirane translates it, "petting a child". In the Tale of Genji This name in Japanese is generally written in kana.

In the Hahkigi (Broom Tree) chapter of the Tale of Genji Tō no Chūjō describes to Genji his affair with a woman who was not his wife. They had a child together which the woman referred to as the 'little pink' or the Yamato nadeshiko. "O, let your compassion touch this little pink with fresh dew!" In time the child became known as Tamakazura.

In Royall Tyler's translation of the Tale of Genji Tō no Chūjō goes to his lover and says:

I could never choose one from the many colors blooming so gaily, yet the gillyflower I feel is the fairest of them all.

In a footnote to this poem Tyler notes: "The tokonatsu ('gillyflower') and the nadeshiko ('pink') are the same flower, but the words have different associations. Nadeshiko refers to the child, tokonatsu to the mother. This is partly because of a play on toko (the 'sleeping place' of lovers) in Kokinshū 167 by Ōshikōchi no Mitsune, to which Tō no Chūjō alludes a line or two later. 'No speck of dust will I allow to soil this bed / gillyflower, abloom since you and I first lay down toegether."

Lady Sarashina (1009-1059), said to be the author of the Bridge of Dreams, refers to the Yamato-nadeshiko or the Japanese pink as 'the flower of Japanese womanhood.'

The photo to the left was posted at Flickr by Pixie Led. |

|

Nagabakama |

長袴

ながばかま

|

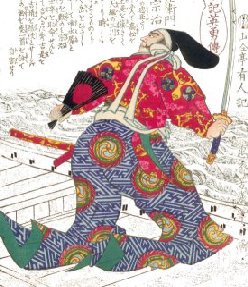

Long ceremonial trousers: To the left is a detail from a print by Toyokuni III. Although the figure is kneeling you can clearly see the length of the right pant leg. It would still be long and dragging even if he were standing.

The image to below is by Yoshiiku from 1867, but representing Shimizu Muneharo

(清水宗治:

1537-1582). As a child my parents sometimes bought me pants which were too long expecting me to grow into them. That saved them on money and shopping and I was instructed to roll up my cuffs. But being a child this didn't always work so well and there were numerous times when I tripped or even fell on my face. Recently that memory was brought back to me when I ran across an entry on nagabakama. I always wondered how and why grown men would wear such attire. Now I know. "The long culottes dragged on the floor as the samurai moved across a room and made it difficult for their wearer to engage in any surprise moves during a court appearance before the shogun." That makes sense.

Quote from: Matsuri: Japanese Festival Arts, by Gloria Granz Gonick, UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, 2002, p. 70. 1

See also our entry on hakama. |

|

There is a good description of the logistics of wearing these trousers in The 47 Ronin Story: "The voluminous legs were overlong by several feet and were supposed to stretch out flatly behind the wearer for aesthetic effect. This required great care in walking and Lord Asano, naturally impatient, felt hemmed in and vulnerable. He had a constant urge to kick holes in the legs and strut in his normal manner instead of mincing along like a woman in a tight kimono. Kataoka finished laying out the cloth so that his master was pointed in the right direction, then bowed deeply and withdrew." |

||

|

|

||

|

Nagamochi |

長持

ながもち

|

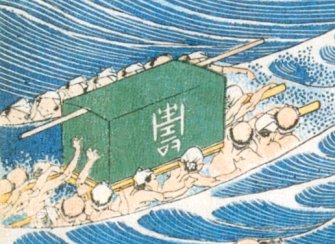

A large oblong chest for clothing and other personal possessions. "Nagamochi (long chest) is now seen only as an ancient relic in old families or among museum collections, but up to the early Meiji ear, it was an important household necessity.... Nagamochi appeared first in the 11th or 12th century..." Originally they may have been made of woven bamboo, but in time they were most frequently made of paulownia or white fir because of their lightness and abilities to stay somewhat dry. In time wealthier households had more elaborate chests which were often lacquered and decorated with family crests. In fact, these became a matter of pride when parents could provide their daughters with such chests as a part of their dowries. Sectioned tansus with drawers were a later invention.

Source and quotes: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 38.

The images to the left are two details from prints by Hokusai. However, I have to admit that I am so abysmally ignorant about the fine points of Japanese furniture that I am only guessing that these images represent nagamochi. The one above is from a Chūshingura scene with one figure standing atop a large orange colored chest. The one below shows laborers struggling to keep a similar chest afloat while fording a river.

The fellow standing atop the chest in the top image is Amakawaya Gihei (天川屋義平) from Act X of the Chūshingura. 1 |

|

Nagare kanjō |

流灌頂

ながれかんじょう |

A consecration cloth - look to the bottom of the image to the left. A cloth suspended by four short bamboo poles over which water is poured. This may be placed above a grave stone. Jim Breen defined kanjō as: "灌頂 【かんじょう; かんちょう】 (n) (1) {Buddh} baptism-like ceremony performed by the buddhas on a bodhisattva who attains buddhahood; (2) {Buddh} baptism-like ceremony for conferring onto someone precepts, a mystic teaching, etc. (in esoteric Buddhism); (3) {Buddh} pouring water onto a gravestone; (4) teaching esoteric techniques, compositions, etc. (in Japanese poetry or music)..." It is the third definition which applies here.

The image to the left is a detail from a Hokushu print in the Lyon Collection. Notice the lotus pads near the cloth. Another Buddhist symbol.

"The nagare kanjō that... was typically erected in running water, along with a wooden stupa, for use in a Buddhist ritual intended to free the souls of women who died during pregnancy or childbirth from the agonies of Blood Pool Hell. The ritual took various forms, but most often involved passersby chanting a prayer and pouring a ladle of water over the cloth; people would continue doing this until the words that had been written on the cloth (or sometimes the red with which the cloth had been dyed) were completely washed away." Quoted from: 'The End of the “World”: Tsuruya Nanboku IV’s Female Ghosts and Late-Tokugawa Kabuki' by Sataoko Shimazaki in the Monumenta Japonica 66/2, pp. 217-218.

"The nagare kanjō was one such ritual. Special burial practices were also developed for pregnant women who had the misfortune to die before giving birth. The fear that the baby might still be alive in the dead woman’s womb led to the practice of separating the mother and baby, either physically or symbolically. By the early modern period, if not earlier, it was common for the fetus to be surgically removed from the dead mother before burial." (Ibid., p. 219) |

|

Nagasaki |

長崎 ながさき |

Port city used for foreign trade 1 |

|

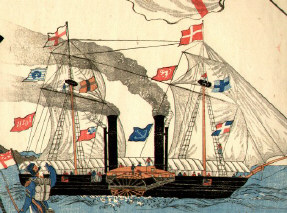

Nagasaki-e |

長崎絵

ながさきえ

|

"The presence of artists in Nagasaki was not accidental since the government employed copyists to reproduce line for line all pictures and paintings that were imported... It is supposed that the Nagasaki prints were designed by such men as a sideline. The prints were usually unsigned and of those few that do carry a signature...little is know of the artists. These prints were published and sold in Nagasaki itself - presumably as souvenirs. The printing techniques were similar to those used in Edo, although the sizes of paper used were often larger and the pigments were slightly different... They all seem to be decidedly rare."

Quoted from: The Art of Japanese Prints, by Richard Illing, Gallery Books, 1980, p. 155.

The center image to the left is the full print. The top and bottom are details of that print. We really want to thank the fellow who sent this image to us so we could post it for you to see. One of these days I will find a way and place to post the full image in a large format. It is truly beautiful and perhaps the finest examples of Nagasaki-e I have ever seen. Of course, that is a personal opinion and simply a matter of taste. |

|

Nage-zukin |

投げ頭巾 なげずきん

|

A gauze hat or hair covering. Literally it means a throw-down (投げ) hood (頭巾). A.L. Sadler in his Cha-no-Yu: The Japanese Tea Ceremony gives an origin for this name: "This Tea-caddy was called 'Nage-zukin' or 'Throw-down-cap,' because when its owner brought it to Shuko for his opinion, the Master was so struck with admiration at it that he instinctively took off the skull-cap he happened to be wearing and threw it on the ground." |

|

Naginata |

薙刀

なぎなた |

Halberd: "The naginata was the principal weapon of foot troops from the 11th century until well into the 15th century. It was the favorite weapon of Buddhist warrior-monks. Early naginata tended to have shorter shafts and longer blades than those of the 17th century onward, when samurai women were trained in their use. Contrary to common belief, the naginata remained in the arsenal of men until the abolition of the feudal system following the Meiji Restoration (1868)." Note that some authors contest the use of the word 'halberd' as a cultural comparison. Others use the term 'glaive'. I take no position. You can draw your own conclusions.

Generally the wooden shaft was 4 to 8 feet in length with a curved blade that was 1 to 2 feet long. At the bottom of the shaft was an iron cap.

Source and quote: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan entry by Benjamin H. Hazard (vol. 5, p. 308)

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Kuniyoshi from ca. 1840.

Several older and some newer sources say it was used mainly by women who fought along side the men. This was said to had begun during the Momoyama period (1563-1602). When it was swung in a circle it was meant to mow down the opponent.

In A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration, and Use of Arms and Armor in All Countries and in All Times: In All Countries and in All Times by George Cameron Stone (Penguin reprint, 1999, p. 463) it states "A Japanese spear with a head like a sword blade curving back very much near the point. It is sometimes called the 'woman's spear,' because women were taught to use it, mainly for exercise, but so that they were prepared to use it in case of necessity. The shafts are lacquered and decorated with metal mountings. Like all Japanese spears it was carried sheathed. ¶ There are three varieties; the most usual one has a tang that fits into the shaft; the naginata-no-saki has a socket on the end of the blade into which the shaft fits. It is the rarest form. The oldest form is the tsukushi naginata which has a loop, or loops, on the back of the blade into which the handle fits."

One account says that Oda Nobunaga, wounded by an arrow, grabbed a naginata to fight off attackers before he locked himself in his quarters and was either burned to death or committed suicide. (Secrets of the Samurai: The Martial Arts of Feudal Japan, by Oscar Ratti and Adele Westbrookp, published by Tuttle, 1991, p. 57) "Among the weapons the samurai woman handled with skill was the spear, both the straight (yari) and the curved (naginata), which customarily hung over the doors of every military household and which she could use against charging foes or any unauthorized intruder found within the precincts of the clan's establishment." (p. 115) In 1843 there were still said to be two school of martial arts which specialized in training using the naginata. (p. 157)

The first kanji character, 薙, in combination with other characters means 'to mow down'. |

|

Nagoya Sanzaburō |

名古屋山三郎 (?) なごや.さんざぶろう |

According to legend kabuki theater was started by a historical female religious figure, Okuni, in the late 16th century. She was said to have had a mentor/lover in Nagoya Sanzaburō. "Born in 1576, the seventh child of a samurai, young Sanzaburō , or Sanza as he is popularly known, studied for the priesthood at a Kyoto temple until 1590. Then, at the age of fourteen, already bored with the austerities of priesthood, he gladly became a page to Gamō Ujisato of Aizu, a Christian daimyō. The death of Ujisato in 1595 brought Sanza back to Kyoto with a fortune bequeathed to him by his late master. ¶ Lombard states in The Japanese Drama that Sanza 'led a life of social freedom, and was popularly known for excellence in social arts, including the Kyōgen' (comic interludes of the Nō). This was the background of the man who it is said became Okuni's mentor as well as lover for a few years. ¶ Sanza, a musician proficient with the fue (flute) and tsuzumi (hand-drum), taught Okuni popular songs to which he wrote ribald lyrics. Together, they borrowed freely from the Nō and Kyōgen. These performances put Okuni on the highest rung of the ladder of popularity. In these, Okuni donned a man's costume and Sanzaburō a woman's, a reversal of their apparel which made them look ungainly for those times, but which the public nevertheless found exceedingly refreshing and humorous. The male members of the audience in particular found the spectacles of a young woman dancing in masculine attire to be highly beguiling and erotic." Quoted from: Kabuki Costume by Ruth M. Shaver, p. 35-36.

"Possibly tired of the gay life, Sanzaburō changed his name to Kyūemon and became a samurai attached to the feudal lord Mōri Tadamasa at Tsuyama in Mamasaka Province. One of the few instances where fully documented evidence about Sanzaburō is obtainable records the fact that Sanzaburō died in 1604 in a quarrel with a fellow retainer." (Ibid., p. 37) |

|

Nakamura Daikichi I |

中村大吉 なかむらだいきち |

Kabuki actor.

|

|

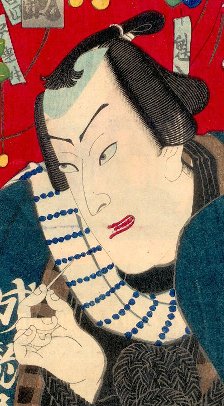

Nakamura Fukusuke I |

中村福助 なかむら.ふくすけ |

The son of Nakamura Tomishirō and the brother of Nakamura Fukusuke II. Fukusuke I (1831-99) debuted in Osaka as Nakamura Tomatarō and later took the name Nakamura Tomasaburō. In 1838 he was adopted by Utaemon IV and moved with him to Edo in 1839 where he took the name Fukusuke. In 1860 he took the name Shikan IV by which he is best known. Extremely versatile and highly respected. In 1893 while performing an acrobatic-flying routine, a chūnori, the wire snapped and he fell breaking his leg. At his age and considering the state of medicine at the time this must have been a life altering event. Click on the image above to see the full print featuring this portrait. |

|

Nakamura Shikan |

中村芝翫 なかむらしガン |

Kabuki actor's name, but here the name of a fictitious twin brother of Nakamura Utaemon III 1 |

|

Nakamura Shikan IV |

中村芝翫

なかむらしガン |

Kabuki actor. |

|

Nakamura Utaemon III |

三代 中村歌右衛門

さんだい.なかむら うたえもん |

Kabuki actor (Shikan 芝翫, Baigyoku 梅玉, 1778-1838). In the early 1820s Utaemon seriously twisted his leg in Edo. In 1825 in Osaka he injured it again and became extremely ill. "A week later he had recovered enough to continue acting through the end of the second month when the New Year's performances ended, but billboards had already announced a 'retirement performance' [isse ichidai kyōgen] for the next month."

Source and quote from: The Theatrical World of Osaka Prints, by Roger S. Keyes and Keiko Mizushima, Philadelphi Museum of Art, 1973, p. 98.

"Utaemon's 'retirement' performance was so well received, and his spirits and health so revived, that he never left the stage, but continued acting without pause until his death at the age of sixty in 1838."

Ibid., p. 100

Michael Jordan retired from basketball only to return to it later. Sugar Ray Leonard retired several times. This is not uncommon with boxers. So, is it any surprise that Utaemon III decided to stay on the stage for another fourteen years after it was announced he was leaving?

|

|

Nakanochō |

中野町

なかのちょう |

The main boulevard running directly through the Yoshiwara or red-light district of Edo. Although it was only a few blocks long it was memorialized in many prints which often showed the procession of the oirans and their attendants dressed in the finest garb.

"The third of the major events of the Yoshiwara had its beginning in 1741. In the spring of that year, proprietors of Nakanochō teahouses conceived the idea of beautifying the boulevard by planting cherry trees and applied for permission from the authorities to do so. It is said they were denied permission for planting trees and were told to use potted cherry plants with blossoms instead."

Quote from: Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan, by Cecilia Segawa Seigle, University of Hawaii Press, 1993, p. 108.

The image to the left is a detail from a polyptych by Toyokuni I showing the oirans and their retinues viewing the cherry blossoms on the Nakanochō. |

|

Nakazori |

中剃り

なかぞり |

Shaving the pate |

|

Namazu |

鯰

なまず |

Giant catfish - believed to be the cause of earthquakes - or so I thought. There is an extremely informative web site written by Gregory Smits at Penn State University which gives the most thorough history of the namazu which I have seen in English so far. Note that Dr. Smits gives a load of links to other namazu imagery or other relevant sites. This is my summary of his information as best I understand it.

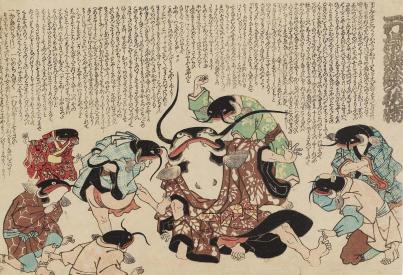

In the image to the left Edoites are attacking the catfish they believe is responsible for the 1855 earthquake. |

|

1. The namazu is Not exactly/actually a catfish: "The Japanese word namazu refers to a wide variety of fish that in English might be called catfish or bullheads. Generally, namazu does not refer to a specific species of fish. In artistic and literary contexts, it is often best to think of namazu less as actual fish swimming around in waterways of Japan than as cultural symbols. And what did namazu symbolize? When it first made an appearance in a work of Japanese highbrow art at the start of the fifteenth century, we cannot determine with certainty what namazu symbolized. As time went on, however, these metaphorical fish gradually began to symbolize disorder. By they [sic] late eighteenth century, the namazu typically stood for one specific type of disorder: earthquakes." A whole genre of namazu pictures developed immediate after the quake of 1855, but in time this fish became a political satire stand in for "...(puffed up) government officials...", etc.

Benkei as a catfish - anonymous - Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Note: The two major on-line kanji sources I use both give namazu as catfish.

2. In the 15th century there were various explanations for earthquakes based mainly on Chinese concepts. One theory is that quakes were caused by dragons which were referred to as namazu. In time this word seemed to morph into meaning a giant catfish. In fact, it was believed that it could be the movement of any large mythic animal which supported the earth. Or, it could even be the result of male and female deities having sex. There were other theories, but I like that last one best.

3. In the early 15th century the concept of catching or controlling a catfish with a gourd became popular. According to Dr. Smits this was not a Zen kōan, but did become a stock metaphor for attempting the impossible. By the 17th century folk art images were sold to pilgrims in the city of Ōtsu. "...one popular motif... was the image of a person, or, more typically, a monkey, suppressing a giant namazu with a bottle gourd." For centuries the term hyōtan-namazu (瓢箪鯰) or gourd-namazu was used for trying the impossible. This term is hardly used or understood today. "During the eighteenth century, the notion developed that the deity of the Kashima shrine [Kashima daimyōjin 鹿島大明神] just NE of Edo (Tokyo) pressed down on an oval-shaped boulder called the 'foundation stone' (kamame-ishi [要石]). This boulder, in turn, pressed down on the head of a huge underground namazu." Occasionally the shrine god would have to leave town for a meeting at the Izumo shrine. At those times Ebisu (or even Daikoku) would take over. If any of them was ever distracted, inattentive or fell asleep the namazu would thrash about causing an earthquake. "(Incidentally, there was an alternative explanation in which the movement of a giant pheasant located at the Kashima Shrine caused earthquakes.)"

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

4. After the quake of 1855 two different types of namazu were considered: The destructive and the restorative. Actually even the destructive kind could act in a restorative manner. Cities had to be rebuilt. Lives had to be made whole again. Many people often felt the quake was retribution for imagined and real ills. This is not far removed from the Judeo-Christian concept behind the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah or even the invocations used by modern theologians in their attempts to explain the destruction wrought on September 11, 2001 and/or the flooding of New Orleans following hurricane Katrina in 2005.

***** In 1964 Cornelius Ouwehand published his Namazu-e and Their Themes: An Interpretative Approach to Some Aspects of Japanese Folk Religion. In that volume he noted that the Kashima deity sometimes suppressed the namazu with a sword too and that in certain prints the giant catfish might be replaced by a whale. In a book review by M. E. in the Monumenta Nipponica it is noted that "The interpretation of the namazu pictures is further complicated by the appearance of the fish in human form, as child, as a man or woman, as a representative of various crafts and trades, but still showing a connection with the gourd or water or both by a distinctive mark on his clothes. At times the namazu as causer of earthquakes is abused and hated, at times he is adored as avenger of social injustices ..." M. E. continues "Besides their religious significance in connection with the earthquake legend we find in the pictures also criticism of existing social conditions through ridicule, irony and puns on words."

Kashima deity napping - ca. 1855 Anonymous - Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Who is the Kashima deity? Ouwehand traced the history according to M.E.: "In the myths the god Kashima is Takemikazuchi which arose from the blood of the fire-god Kagutsuchi when his father Izanagi killed him with his sword. Takemikazuchi is the sword-fire-god and thunder-lightning god at the same time." M. E. is critical of the jumble of concepts dealt with by Ouwehand. However, I wasn't quite sure which jumble he was referring to. If it was the dual nature of the namazu then time and scholarship seem to be on Ouwehand's side. |

||

|

|

||

|

Nami |

波 なみ |

Waves |

|

Nanushi |

名主 なぬし |

Censors (seals): Starting in ca. 1790 the government sought to keep better control over the production or woodblock prints. They wanted to make sure that nothing seditious (or overly luxuriant) was being published. The kiwame (極) was the first general seal used in one form or another for decades. "Then in 1842, in the thirteenth year of Tempō, under a reform instituted by Mizuno (水野) , Lord of Echizen (越前守), still another, more rigid, regulation was enforced, and the kiwame seal was replaced by that of the 'nanushi, a censor."

Source and quote from: "Ukiyoe: Some Aspects of Japanese Classical Picture Prints", by Shigeyoshi Mihara, Monumenta Nipponica, Vol. 6, No. 1/2. (1943), footnote 13, p. 257. |

|

In an interesting 1913 article in "The International Studio" (p. 313) entitled "The Dating of Japanese Colour-Prints in 1842" J. J. O'Brien Sexton quotes a passage from Captain F. Brinkley's Japan: Its History, Art, and Literature (vol. 7, p. 50): "At one time (1842) and that not by any means the Golden Age of the Art, the Yedo Government, in a mood of economy, deemed it necessary to issue a sumptuary law prohibiting the sale of various kinds of chromo-xylographs - single-sheet pictures of actors, danseuses, and 'dames of the green chamber': pictures in series of three sheets or upwards, and pictures in the printing of which more than seven blocks were used. The prohibition held for twelve years only -"

[Chromo-xylographs = colored woodblock prints; 'dames of the green chamber' = courtesans, i.e., prostitutes of the Yoshiwara.]

According to Sexton the nanushi were administrative counselors, i.e., "Toshiyori", who had nothing to do with the production of the woodblock prints. (p. 314)

Peter Kornicki in The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth Century (p. 351-2) notes that from 1761 to 1786 "...some artist's signatures did appear on shunga, often disguised as signatures on screens or hidden in the design. In 1842, in the midst of the Tempō reforms, the Edo authorities noticed that prints were already being published with faked censorship seals suggesting that they had been approved in the hope of getting around the new restrictions, and surviving copies of a particularly flagrant example were confiscated. Later, in the late 1840s and early 1850s, some prints, such as a triptych by Utagawa Kunisada which contravened the recent ban on the representation of actors and courtesans in prints, carry the imprint of a seal advising retailers not to hang it up for display but to sell it 'under the counter' (shitauri シタ売). This is in a sense a form of self-censorship, but it also demonstrates the willingness of publishers to bend the rules." It was also clear that the government "...did not have either the resources or the will to control the circulation of illicit or subversive..." printed matter.

Properly speaking a nanushi was a headman or leader of a village or town.

Andreas Marks defines the term nanushi: "With the enactment of the Tenpō reforms in 1842, the censorship system was changed and from the sixth month on, nanushi 名主, minor government officials, were selected to carry out the approval by applying their name seal to prints." |

||

|

|

||

|

Naraku (sometimes naraka) |

那落 ならく |

From a Sanskrit word for 'hell' (नरक): "one of the three negative modes of existence... The hells are places of torment and retribution for bad deeds; but existence in them is finites, i.e., after negative karma has been exhausted, rebirth in another, better form of existence is possible. Like the buddha paradises... the hells are to be considered more as states of mind than as places. ¶ Buddhist cosmology distinguishes various types of hells, essentially adopted from Hinduism. There are hot and cold hells divided into eight main ones, among which the Avici is the most horrible, each surrounded by sixteen subsidiary hells. The inhabitants of the hells suffer immeasurable torment for various different lengths of time. They are hacked into pieces, devoured alive by birds with iron beaks, and cut up by the razor-sharp leaves of hell trees. The hells are ruled by Yama." Quoted from: The Shambala Dictionary of Buddhism and Zen, p. 155. |

|

Nashi |

梨

なし |

Japanese pear: This fruit has no particular connection with ukiyo-e. However, I am reading The Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon in the Penguin Classics version, translated and annotated by Ivan Morris. This is a book everyone interested in traditional Japan should read. Sei Shōnagon is a woman who doesn't seem to have thought twice about expressing her prejudices and one of them was about the nashi. It was too juicy not to include here. In her section on flowering trees she said: "The blossom of the pear tree is the most prosaic, vulgar thing in the world. The less one sees this particular blossom the better, and it should not be attached to even the most trivial message. The pear blossom can be compared to the face of a plain woman; for its coloring lacks all charm. Or so, at least, I used to think. Knowing that the Chinese admire the pear blossom greatly and praise it in thier poems, I wondered what they could see in it and made a point of examining the flower. Then I was surprised to find that its petals were prettily edged with a pink tinge, so faint that I could not be sure whether it was there or not." She then recalls that the pear blossom was compared to the face of Yang Kuei-fei and decides that "...it really is a magnificent flower."

Two items: Morris notes that Sei Shōnagon is mistaken about the comparison of the flower to the face of Yang Kuei-fei. Actually her visage was compared to the delicacy of jade. And, in a footnote he adds: "It was customary to attach flowers or leaves to one's letters; the choice depended on the season, the dominant mood of the letter, the imagery of the poem it contained, and the colour of the paper."

For our comments on the Yang Gui-fei motif in Japanese art go to our entry on our Yakusha thru Z index/glossary page.

In the Chinese poem, "A Song of Unending Sorrow", by Bai Juyi's (772-846) Yang Gui-fei's spectre is described after death as thus:

Her face, delicate as jade, is desolate beneath the heavy tears, Like a spray of pear blossoms in spring, veiled in drops of rain.

The image of the pear blossoms is from the web site operated by Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. |

|

Nazuna |

薺

なずな |

Nazuna or shepherd's purse were said to have been sold by vendors at temple complexes during the Edo period. People would "...take these flowers home and offer them to the Buddha. As they consider the nazuna to be a charm against insects, they hang them with a thread in their andon (行燈, lamps with paper shades)." Quoted from: Ancient Buddhism in Japan by de Visser, p. 57

The photo to the left is being shown courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/. |

|

|

The photo of the lotus pods which we have used as wallpaper is by Kenpei and was posted at Commons Wikimedia. |

|

|

LINKS TO OUR OTHER INDEX/GLOSSARY PAGES Click on any of the pages listed below!

|

||

HOME

HOME