JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

Hotoke thru Igaya Kan'emon |

|

|

|

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Hotoke, Hyakunichi, Hyō, Hyōbanki, Hyōshigi, Hyōtan, I, Ichiba machi, Ichikawa Danjūrō VIII, Ichikawa Danjūrō IX, Ichikawa Ebizō I, Ichikawa Ebizō V, Ichikawa Kodanji IV, Ichikawa Monnosuke III, Ichikawa Omezō I, Ichikawa Sadanji I, Ichimai-e, Ichimatsu moyō, Ichimura Uzaemon XVII, Ichinotani futaba gunki, Ichirō, Ichirō Gafu, Ichō, Ichō mon, Igaya Kan'emon

仏, 百日, 俵, 評判記, 拍子木, 瓢箪, 井, 市場町, 市川団十郎, 八世代市川団十郎, 九世代市川団十郎, 初代市川海老蔵, 市川海老蔵 (5代目), 市川小団次, 市川門之助, 市川男女蔵, 一枚絵, 市松, 市村羽左衛門十七代目, 一谷嫩軍記, 一老, 一老画譜, 銀杏, 銀杏紋, 伊賀屋勘右衛門 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|||

|

|

|||||

|

Hotoke |

仏 ほとけ |

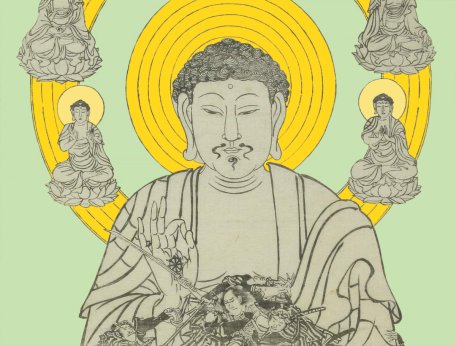

Buddha (or the dead): When I set out to add an entry for the Japanese name for a buddha - there are a myriad of buddhas - I started with the image to the left. Little did I know what I would find: hotoke also means 'the dead.' I am laying bare my ignorance of Japanese culture here for all to see, but I don't care because I love the adventure this project has opened before me. That said, now on to the word itself.

"During the Tokugawa period, many people knew what hotoke meant. After receiving a posthumous Buddhist name and after one's funeral was performed, it was believed that a deceased person was transformed into a deity. In addition, many people started calling the dead hotoke which is still heard in horror movies or TV detective stories in Japan nowadays. The religious feelings once found in this word have now completely disappeared. ¶ As long as Buddhist funeral and memorial services were properly held, anyone could become a hotoke after death; in this way, it was unnecessary for people to seek spiritual peace through religion." (Quoted from: Why are the Japanese Non-religious?: Japanese Spirituality : Being Non-religious in a Religious Culture, by Toshimaro Ama, published by the University Press of America, 2004, p. 23) |

|||

|

Toshimaro Ama, quoted above, notes that the Chinese used the character 仏 for Buddha. Butsu is the native Japanese pronunciation, but hotoke is based on an approximation of the Chinese one which sounds like 'hoto'. "Since ke means figure, hotoke means figure of the Buddha though this theory has yet to be confirmed. According to Yanagita, hotoke means 'an enshrined spirit,' in front of which an offering of food was placed in a container called hotoki." (Ibid., pp. 22-3) Aruga Kizaemon (有賀喜左衛門) disagreed with Yanagita's interpretation "...since the word hotoke was found in the Nihonshoki [日本書紀], which was compiled in the early eighth century, it was already widely used in society. According to Aruga, hotoke came from the word futoki, meaning 'the branch used in the ceremony to worship ancestors to bring their spirits back,' and that when Buddhist rituals were adopted, the name continued to be used." (Ibid., p. 23)

The image below is a detail from a print by Toyohiro. Clearly the large central figure is the Buddha surrounded in his halo by smaller figures of buddhas. Initially I thought these smaller images were bosatsu (菩薩) or bodhisattvas, but on closer observation I think I was wrong. Also, ignore the fighting figure below.

I was led on this quest because of the odd nature of the use of such a sacred word like hotoke for such disparate meanings. However, it wasn't hotoke used for Buddha and dead people that got me going, but rather the use of hotoke for the name of a courtesan in the Heike monogatari (平家物語) first recounted in the early 14th century. In the 12th century shirabyōshi (白拍子) dancing became popular. It got its name from the long white overshirt worn during their performances. While both men and women participated they all wore men's clothes. Oh, and don't forget, the women also frequently acted as prostitutes. ¶ At the time when Taira no Kiyomori (1118-81: 平清盛) ruled his actions were both extravagant and capricious. He lavished gifts on one family of shirabyoshi dancers and one, Giō (祇王), in particular. She had his attention for three years and much envied by her peers. That is until one day when a sixteen year old beauty named Hotoke arrived from Kaga Province. "High and low in the city praised her to the skies. 'There have been many shirabyōshi from the old days on, but never have we witnessed such dancing,' the people said." Frustrated by not being invited to perform before Kiyomori she presented herself at his residence. " 'What is this? Entertainers like her are not supposed to present themselves without being summoned. What makes her think she can simply show up like this? Besides, god or Buddha, she has no business coming to a place where Giō is staying. Throw her out at once,' Kiyomori said." AT this point Giō argued that the girl was young and inexperienced and that the shogun should at least listen to her sing. So, Kiyomori relented an asked her to sing him an imayō (今様), a modern song. Hotoke sang beautifully so a drummer was called and she was to dance too. "Kiyomori was dazzled and swept off his feet by the brilliance of her performance, which revealed a skill quite beyond imagination." Ostensibly embarrassed, Hotoke asked to be allowed to leave when she found out that Giō had requested the performance. She stated this several times [The lady doth protest too much, methinks.], but by now Kiyomori had decided to make Hotoke his mistress and ordered that Giō be expelled. All of the gifts of rice and money which Kiyomori had given to Giō and her family were now transferred to Hotoke. Insult to injury, but it didn't stop there. ¶ Sometime later Kiyomori basically ordered Giō to come back to court to perform for Hotoke because she seemed bored. Giō didn't want to go, but her mother pointed out the hardship which would befall the family if she didn't. So... with great reluctance Giō returned to court. However, when she did perform it was an imayō which she sang through her tears:

In days of old, the Buddha was but a mortal; in the end we ourselves will be Buddhas, too. How grievous that distinctions must separate those who are alike in sharing the Buddha nature.

While others were moved Kiyomori's reaction was to order Giō to return often to entertain his new lover. On the verge of suicide Giō's mother argued against it. Instead the mother and her two daughters shaved their heads becoming Buddhist nuns, went to live in humble seclusion in the Saga mountains and prayed for salvation murmuring Buddha-invocations. At least a year later someone knocked at their door startling them. Even more startling was who the visitor was. It was Hotoke who - in her own way - begged their forgiveness. She cried "A woman is a poor, weak thing, incapable of controlling her destiny." The message of Giō's performance had touched her and she asked Kiyomori to let her go, but he refused. Hotoke had come to realize that all was illusion and that temporal joys were completely transitory. She knew that at some point Kiyomori would replace her with a younger beauty like he had her predecessor. She also felt that she was encumbering her soul to such a degree that it would be eons after her death before she would ever be saved from the torments of hell. Then she removed her hood for her hosts to see that she too had shaved her head and become a nun. Then Hotoke pled: "...please forgive my past offenses... I want to recite Buddha-invocations with you and be reborn on the same lotus petal."

Source and quotes from: The Tale of the Heike, by Helen Craig McCullough, published by Stanford University Press, 1988, pp. 31-7.

[Note: Fritz von Papen urged Hindenburg to name Hitler as Chancellor of Germany assuring the aged President that he could control the Nazi leader and we all know how that came out. But that is history while in a cinematic vein there is always the story of Margo Channing, a woman at the top of her game, who lets young, sycophantic Eve Harrington into her life only to loose her men, his theatrical roles and her pride. That was in "All About Eve". The pattern repeats itself.]

In Ancestor Worship in Japan by Robert John Smith (published by Stanford University Press, 1975, p. 50) the author states: "When the Japanese speak of the individual or collective dead, they most commonly use the word hotoke (buddha). The source of this uniquely Japanese notion that all men become buddhas merely by dying is by no means clear. Certainly nothing in orthodox Buddhism suggests such a happy automatic fate, nor does the idea square with the concept of rebirth. Even the wandering spirits are a kind of hotoke. It may well be that the explanation lies in a fundamental misunderstanding of the idea of nirvana (Japanese nehan [涅槃]) dating from a very early period of Japanese history..." Smith continues: "In some senses, then, hotoke has come to mean simply the spirit of the dead, and to say that a man has become a buddha is only to day that he has died. The household altar quite commonly contains no representation of a buddha, but only the memorial tablets for the dead of the house." (Ibid., p. 52) Ronald P. Dore took a survey of some of the Japanese citizens of one district in Tokyo. He asked them if hotoke and Hotoke were the same thing. 51% said they are different. (City Life in Japan: A Study of a Tokyo Ward, published by the University of California Press, 1958,) |

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

Hyakunichi |

百日

ひゃくにち |

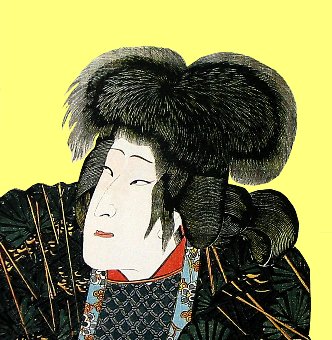

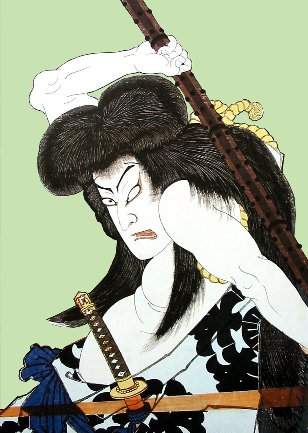

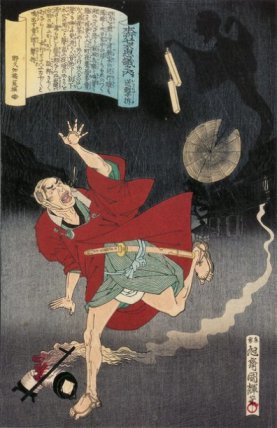

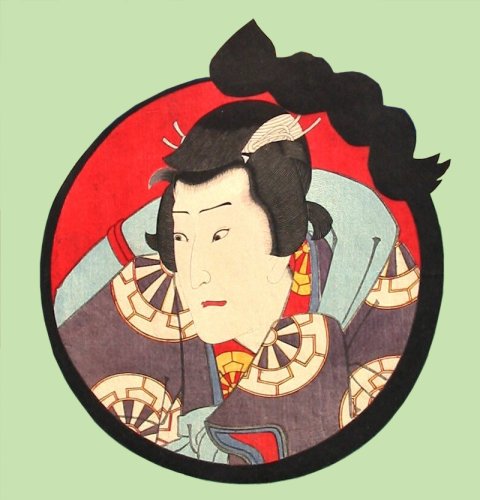

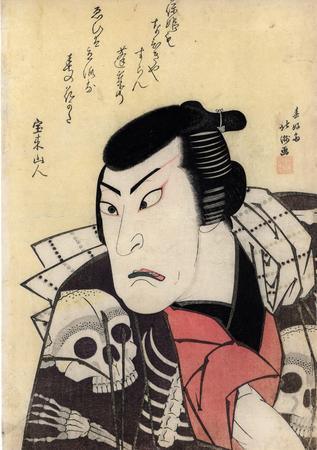

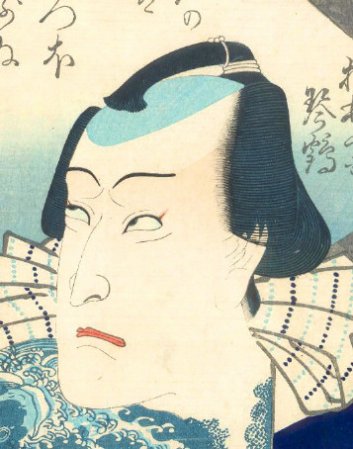

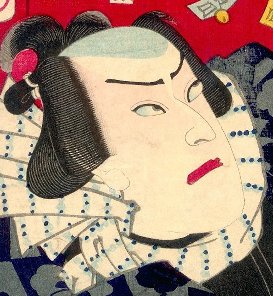

A type of wild, bushy wig (鬘) worn by villains meant to indicate a head of hair uncut for at least 100 days. It is also called a daibyaku. There is also a 50 day look in the gojūnichi. "Long hair stands up bristle-like from the crown. The wig's name is highly conventional as no one's hair could grow this long in 100 days.... The main version, the hyakunichi no tare, includes a long pony tail bound near the bottom with a gold rope...." The "...softness of the top hair also suggests that the character is not well, perhaps due to an excess of fear and anger." (Quote from: New Kabuki Encyclopedia by Samuel L. Leiter, p. 179)

The figure on the left (with the red ground which we added) is of Kagekiyo by Kuniyoshi. Both fellows shown above are from prints by Kunichika. The one on the left represents Omatsu and the one on the right Yamanaka Tōtarō. |

|||

|

Hyō |

俵 ひょう |

Bale of rice - There is a very early publication in French, 1728, Ceremonies et Coutumes Religieuses des Peuples Idolatres, which describes Daikoku seated on a bale of rice. "Le bale de ris est chez les Orientaux l'emblême de l'abondance."

In 1732 Englebert Kaempfer published his Histoire naturelle, civile et ecclésiastique de l'Empire du Japon, originally written in German, in which he referred to Daikoku as the god of merchants and one of his symbols of wealth was rice.

The image to the left, from the Lyon Collection, is an image isolated from a print by Toyokuni I. It shows a woman who is a stand-in for the god Daikoku, the god of prosperity, who is often seen with his mallet and occasionally bales, too. Click on the image to see the full, unadulterated print.

Below is a print by Shunzan in the Rijksmuseum. It shows Daikoku leaning again a bale of rice, with his mallet in his right hand and his left hand on a rat, another symbol of prosperity. We found this image at commons.wikimedia.

|

|||

|

In The Scheming World by Ihara Saikaku it says: "When New Year's Day dawns, men sell pictures of Saikoku, the god of wealth, calling out, 'Get your lucky fortune! Get your bales of luck!' " |

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

Hyōbanki |

評判記 ひょうばんき |

Written commentary on notable events or persons, i.e. a critique: "...the earliest examples of this type of manual published in Japan dealt with prostitutes and were more guidebooks than genuine critiques. First practical guides appeared in the 1620s to help people visiting the pleasure quarters and by the 1680s there were more than a hundred of these books on the market." These were called yūjo hyōbanki or 'critiques of prostitutes'. Source and quote from: "The Audience Evaluated. Shikitei Samba's Kyakusha hyōbanki" by Jacob Raz, Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 35, #2, Summer 1980. |

|||

|

Hyōshigi |

拍子木

ひょうしぎ

|

Wooden clappers used in kabuki theater "...for sound effects such as running feet and clashing swords." (Quoted from: The Actor's Image: Print Makers of the Katsukawa School, Timothy Clark, Osamu Ueda and Donald Jenkins, Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 264.)

"Another characteristic kabuki sound that may be classified with ceremonial music is the wooden clappers known as hyōshigi (or simply as ki). These not only mark the beginning of a play, but at times - as wehn they are beaten while the curtain is being drawn - become almost an integral part of the production... [or]...to point up the moment when an actor strikes a mie." (Quote from: Kabuki, by Masakatsu Gunji, published by Kodansha International, 1985, p. 51.)

This humorous Kuniteru image was posted by Tobosha at commons.wikimedia.

"Wooden clappers (hyōshigi) are one of the things peculiar to Kabuki. It is simply a matter of banging together two sticks of white oak, but one side of each is carved so that it has a convex shape. These two sides are banged together, and the accepted view is that the best sound is only produced if they are cut back form the same piece of wood." (Quote from: Japan on Stage: Japanese Concepts of Beauty as Shown in the Traditional Theatre, by Kawatake Toshio, published by 3A Corporation, Tokyo, 1990, p. 115.)

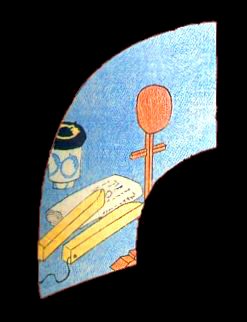

The image to the left of the fan is a detail from a print by Kunisada from ca. 1826.

A Popular Dictionary of Buddhism by Christmas Humphreys says: "Two solid pieces of hard wood used as clappers in Rinzai Zen monasteries to mark periods in the meditation. The blocks may be six inchest [sic] to twelve inches long; the noise made is startling."

"In kabuki, the drawing of a hikimaku [draw curtain] was accompanied by the bangs of hyōshigi (wooden sticks) that were clapped against each other in various sound patterns to signal opening and closing of scenes."

We found the lower image to the left at commons.wikimedia. |

|||

|

Hyōtan |

瓢箪 ひょうたん |

Gourd: Dower tell us that no family adopted the gourd as a crest because it of its baseness since it was often used to carry saké and saké led to licentiousness. (Source: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, pp. 54-5)

Despite what Dower says about the humble gourd Hideyoshi took it as one of his signifying crests. Of lowly birth his family was well below the level of families which would use a crest or mon. "...when, in 1575, [Hideyoshi]... obtained a command, he adopted a water gourd as his emblem, and added another one for every victory he gained, until the number grew into a large bunch, and he was called The Lord of the Golden Water Gourds." (Quoted from: The Story of Japan, by R. Van Bergen, published by American Book Company, 1897, p. 74.)

Nikolai Gogol tells us in "The Diary of a Madman" that "There are plenty of instances in history when somebody quite ordinary, not necessarily an aristocrat, some middle-class person or even a peasant, suddenly turns out to be a public figure and perhaps even the ruler of a country." So the story of the peasant Hideyoshi rising to top and unifying Japan on the way is not absolutely unique. The first Han emperor was said to have been born a peasant. And while Napoleon wasn't born of common stock he wasn't in line to rule an empire until he crowned himself. Since then many madmen have thought they were Napoleons or at least the movies would make us believe so. Gogol's madman was a lowly clerk but he believed himself to be the King of Spain. Perhaps that is why we could say he was out of his gourd. (The madman also thought dogs could talk and that he read their written correspondences.)

Below is a beautiful photograph of a gourd taken by Pixeltoo. This person was placed in the public domain at http://commons.wikimedia.org/.

|

|||

|

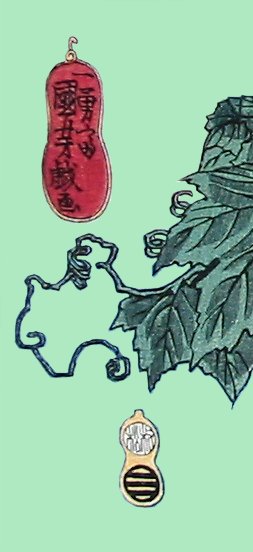

Timothy Clark tells us that Kuniyoshi used the gourd as a hidden, veiled reference to Hideyoshi. It was illegal to portray Hideyoshi directly so the gourd acted as a symbolic substitute which Kuniyoshi's contemporaries would recognize.

The above image is a detail from a Kuniyoshi fan print design. Notice the head, arms, legs, torso and gourd are all created from gourds. Pretty darned amazing. Even the gourd man's member is the top of a gourd inverted. Makes me laugh.

Not only was the figure on the fan print created wholly out of gourds, but Kuniyoshi placed his signature within this device -seen in red cartouche shown above - while the publisher, Iba-ya Senzaburō, and date seal appear in the yellow gourd almost as though it were conspiratorial. Maybe it was simply an agreement made by like minds.

Other publishers in both Osaka and Edo also used the gourd to frame their logos. |

|||||

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

I (pronounced ē) |

井

い

|

A well motif used in fabric designs and family crests or mons. This pattern is also referred to as an igeta (井桁) or well-curb, i.e., the border around the mouth of a well. John W. Dower also notes that it can be called an izutsu (井筒). He added: "The well crib was one of the most popular motifs in Japanese heraldry and stands as an excellent example of the virtuosity of Japanese artists in elaborating upon a simple basic theme. Unlike many other motifs, it does not appear to have conveyed several layers of meaning, but was selected primarily for its simple beauty, and for denotative purposes. The latter function derived from the fact that a great variety of Japanese surnames contain the ideograph for i..." (Quoted from: The Elements of Japanese Design, p. 128)

Some of the families that used the i as their crest or mon: the Inoue (井上) as daimyō at Hamamatsu in Totomi, at Shimotsuma in Hitachi and at Takaoka in Shimosa; the Ii (井伊 or いい) as daimyō at Yoita in Echigo and Omi in Hikone; the Sakai (酒井) as daimyō at Katsuyama in Awa, at Obama in Wakasa; the Imai (今井); the Mizoguchi (溝口) as daimyō at Shibata in Echigo; the Nagai (長井); Wakabayashi (若林); Niinomi (新家); Demura (出村); Ide (井出); Orii (折井); Usui (臼井); Tamei (爲井); Kawashima (川島); Komai (駒井); Yamashita (山下); Miyazaki (宮崎); and Kamei (亀井) as daimyō at Tsuwano in Iwami. (Source: Mon: The Japanese Family Crest by Kei Kaneda Chappelear and W. M. Hawley, p. 79) |

|||

|

Ichiba machi |

市場町 いちばまち |

"Market towns (ichiba machi) originated in the Kamakura period as areas the government authorized to sell produce and other goods on certain days of the month." (Quoted from: Handbook to Life in Medieval and Early Modern Japan by William Deal, p. 61) |

|||

| Ichikawa Danjūrō VII (cf. Ichikawa Ebizō V) |

市川団十郎

いちかわ.だんじゅうろう |

||||

|

Ichikawa Danjūrō VIII |

八世代市川団十郎

ばちせだ.いちかわ.だんじゅうろう |

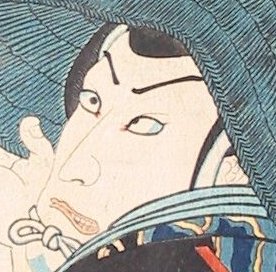

Popular Kabuki actor (1823-54) who committed suicide at the height of his popularity. The son of Danjūrō VII. 1, 2 This portrait was created a number of years after Danjūrō VIII had died. To see why this seems credible please click on the image above. |

|||

|

Ichikawa Danjūrō IX |

九世代市川団十郎 いちかわ.だんじゅうろう |

Actor 1839-1903: One of the greatest actors of the Meiji period (1868-1912). The fifth son of Danjūrō VIII and one of his concubines. "He was soon adopted by actor manager Kawarazaki Gonnosuke VI and raised by him. His upbringing was then extraordinary, Gonnosuke's wife, determined that the boy should become important, made him train intensively in acting and dancing, as well as in classical Japanese art and learning, including the tea ceremony, Chinese literature , painting and calligraphy."

The image of Danjūrō tweezing in a mirror shown to the left is by Kunichika and dates from 1871. To see the full print click on the image.

For his connection with the dramatist Mokuami and for a discussion of the actor's influence on the theater click on the #1.

|

|||

|

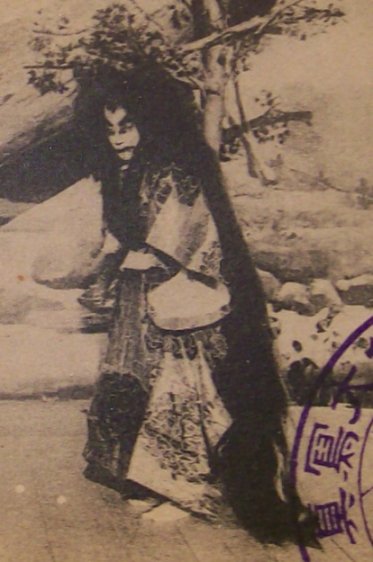

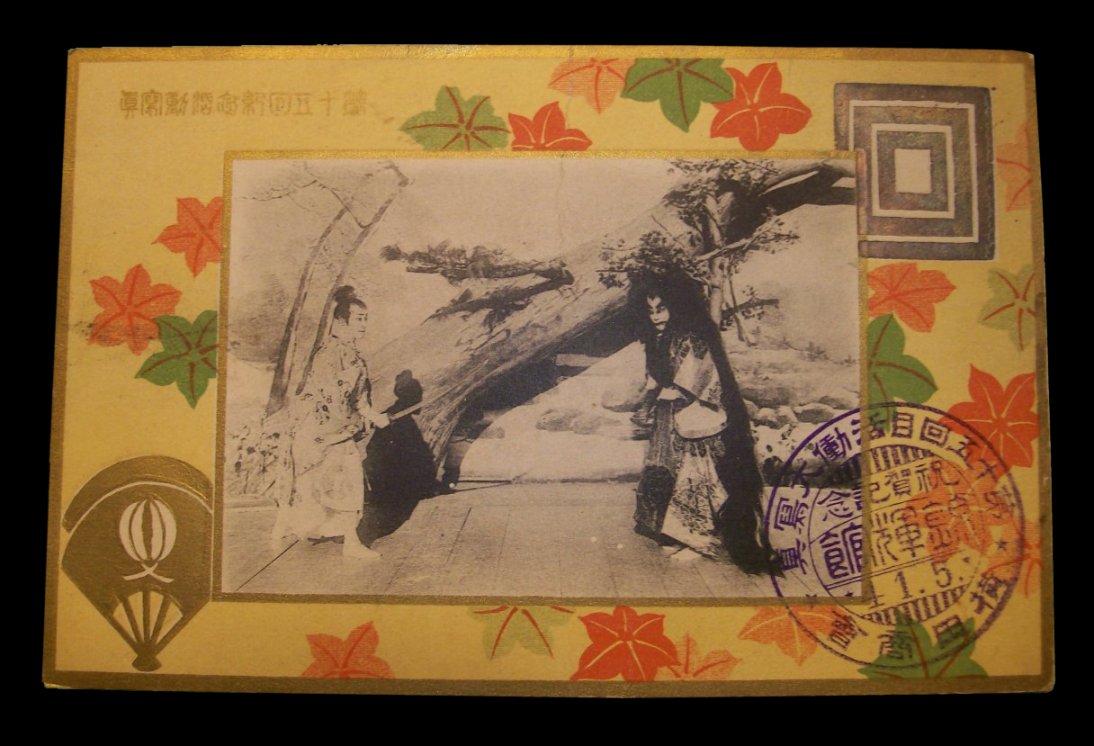

Some time back we received an email from Dan in Nebraska asking about a postcard he had just acquired. This led to a short correspondence and an wonderful series of discoveries - due mainly to the diligent research of Dan. What he found was remarkable. (Below is the image of the card itself.) ¶ In A Hundred Years of Japanese Film: A Concise History, with a Selective Guide to Videos and DVDs by Donald Ritchie and Paul Schrader (published by Kodansha in 2001, p. 18) it states clearly that Danjūrō took a dim view of the new field of cinematography. "Originally the leading kabuki actor Ichikawa Danjuro IX was against the idea of motion pictures, dismissing them as (apparently unlike kabuki) merely vulgar amusement. In fact, kabuki actors - thought not Danjuro himself - had already appeared before the Lumière cameramen when they visited Japan, but this apparent contradiction was acceptable since those performances were for export. However, Danjuro was eventually won over by the argument that his appearance would be a gift for posterity." ¶ In 1899 Shibata Tsunekichi "...decided to shoot in a small outdoor stage reserved for tea parties behind the Kabuki-za, but that morning there was a strong wind. Stagehands had to hold the backdrop, and the winds carried away one of the fans Danjuro was tossing..." ¶ The theatrical setting was for Maple Viewing or Momiji-gari. Here Danjūrō IX, on the right, is paired with Onoe Kikugorō V. Sure the card shown below is a product of this session - this historically fascinating session.

We want to thank Dan of Nebraska for bringing this card to our attention and for letting us post it. He has said that he is interested in selling this card. If anyone wants to purchase this postcard they should contact us at jv@printsofjapan.com and we will put you in touch with Dan directly. |

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

Ichikawa Ebizō I |

初代市川海老蔵

いちかわ.えびぞう |

“Ichikawa Ebijūrō I (1777-1827)

was also known by his pen name Shinshō and his art name Sankitei. His clan

sobriquet (yago) was Harimaya. Initially a disciple of Danzō IV using

the name Ichizō, he later became a student of the great Ichikawa Danjūrō VII

in Edo, through the introduction of Utaemon III (Shikan). In 1815 Danjūrō

awarded him the acting name Ebijūrō (derived from Danjūrō’s two name Ebizō

and Danjūrō) and the pen name (haimyō) Shinshō, which takes a

character from Danjūrō’s own pen name Sanshō. After seven years in Edo, he

returned to Osaka in the tenth month, 1815, to re-launch his career as a

rough, villain-role specialist (jitsuaku, katakiyaku). He

mostly played opposite Shikan, but also performed with Rikan I and Rikan

II.”

The image of Ichikawa Ebijūrō I to the left is from ca. 1822 and is in the Lyon Collection. The print is by Hokushū. |

|||

|

Ichikawa Ebizō V |

市川海老蔵(五代目)

いちかわ.えびぞう |

Actor 1791-1859. He also performed under the name Danjūrō VII. The father of Danjūrō VIII - see above. |

|||

|

Ichikawa Kodanji IV |

市川小団次

いちかわ.こだんじ |

Kabuki actor 1812-66. 1

Above is a detail from an 1847 diptych by Toyokuni III showing Kodanji IV dancing on the edge of a sword. |

|||

|

Ichikawa Monnosuke III |

市川門之助

いちかわもんのすけ |

Kabuki actor 1794-1824. |

|||

|

Ichikawa Omezō I |

初代市川男女蔵

いちかわ.おめぞう |

Kabuki actor 1781-1833. 1

Omezō I was said to have been overshadowed in Edo by the arrival of Utaemon III. "A critical work of the period quoted in Kabuki Nenpyō (Kabuki chronology) says, " A great ball of fire has come to Edo from Osaka. [Ichikawa] Omezō [I] has been quite burned out, [Bandō] Mitsugorō [III] is in danger from the accompanying gale, [Matsumoto] Kōshirō [V] was quite disposed of." Quoted from: A Kabuki Reader: History and Performance edited by Samuel L. Leiter, article by Charles J. Dunn, p. 79. |

|||

|

Ichikawa Sadanji I |

初代市川左団次

いちかわさだんじ |

Kabuki actor. |

|||

|

Ichimai-e |

一枚絵 いちまいえ |

A single, stand-alone, woodblock print. (See also nimaitsuzuki and sanmaitsuzuki.)

Ichi (一), of course, is the word for 'one', while mai (枚) is the counter word for sheets of paper.

This is also referred to as an ichimaizuri (一枚摺). |

|||

|

Ichimatsu moyō |

市松

いちまつ

|

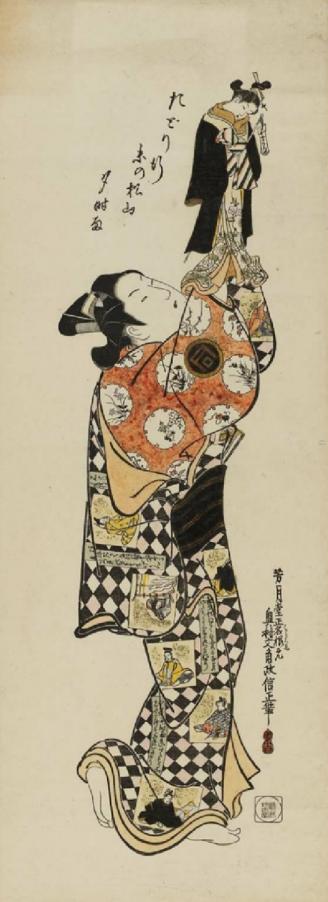

A checkered pattern. Also referred to as ishi-datami (石畳) which literally means 'paving stones'.

There are other words which mean plaid: benkeijima (弁慶縞) is one of them and could be translated somewhat like 'strong man's stripe'; and benkeigoushi (弁慶格子) which would substitute 'grid' or 'lattice work' at the end. I have no idea about the origin of this phrase, but will let you know if I find out.

One English-Japanese dictionary from 1876 states that benkeijima is composed of 3 shades while ichimatsu is made up of only two. I have no way of confirming this, but it seems reasonable. (Source: An English-Japanese Dictionary of the Spoken Language, by E.M. Satow and Ishibashi Masakata, Trübner & Co. and Lane, Crawford & Co., p. 229) |

|||

|

Above is an Okumura Masanobu print of Sanogawa Ichimatsu with a puppet It is from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

Ichimura Uzaemon XVII |

十七代目市村羽左衛門 いちむら.うざえもん じゅうしちだいめ |

Actor - Born 1916 1 |

|||

|

Ichinotani futaba gunki |

一谷嫩軍記 いちたに.ふたばぐんき |

Kabuki play: "Chronicle of the battle of Ichinotani" 1 |

|||

|

Ichirō |

一老 いちろう |

One of Gakutei's art names |

|||

|

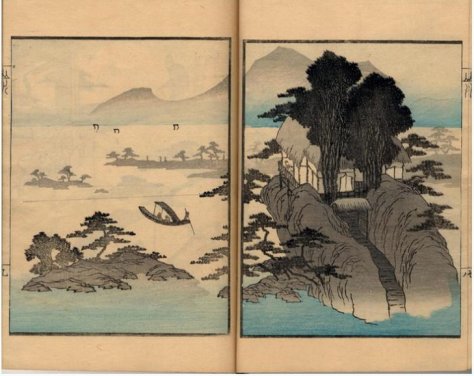

Ichirō Gafu |

一老画譜 いちろうがふ |

"Ichiro's Picture Album" (see listing above)

The double page sheets shown above come from this publication come from the Lyon Collection. Click on it to learn more. |

|||

|

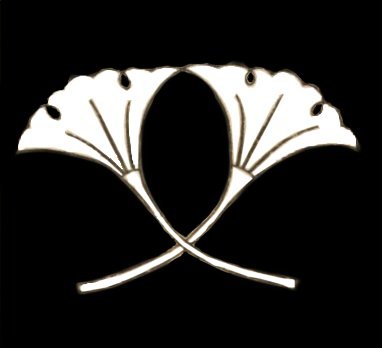

Ichō |

銀杏

いちょう |

Ginko: The leaf of this tree is often related to female fertility. It's "...golden colour brings good fortune, and... is therefore kept in a woman's chest of drawers."

But the most remarkable feature of the gingko tree and hence its association with female fecundity is due to a rather strange aspect of its growth. "Trunk and branches produce queer pendent overgrowths which look like woman's breasts; it is, therefore, a 'milk-tree', a tree of progeny."

Quotes from: U. A. Casal, "Lore of the Japanese Fan", Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 16, no. 1/2, 1960, pp. 84-85.

The images shown to the left and below are used courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm.

|

|||

|

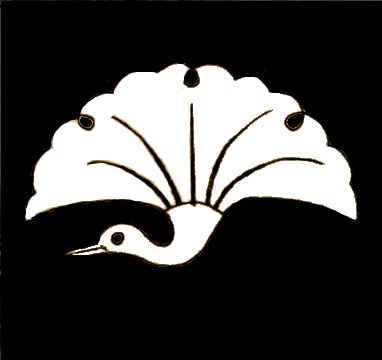

Ichō mon |

銀杏紋

いちょう.もん |

Ginko crest: Often used as a decorative motif. Brought to Japan from China this tree dates back several hundred million years. For whatever reasons, symbolic or because of its beauty and uniqueness, it can frequently be found at temples and shrines and was selected to border the moat surrounding the Imperial Palace in Tokyo.

Long before there was that famous Superman question - you know, the one about a bird or a plane - there was the ginko/bird. The crest shown to the left at the top of this section is a wonderful example of Japanese creativity. Someone, i.e., a Japanese 'designer' must have watched a ginko leaf falling and thought - in Japanese of course - "That looks a lot like a swooping bird." Ergo this particular crest.

|

|||

|

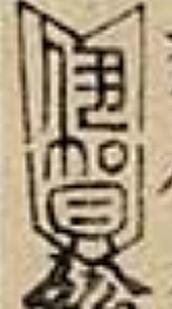

Igaya Kan'emon |

伊賀屋勘右衛門

いがやかんえもん |

This fellow was both a censor and a publisher. To the left is his censor's gyōji seal from an 1811 Kunimaru print in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The full image can be seen below. Seen on prints in a period from III/1811-1814.

|

|||

|

LINKS TO OUR OTHER INDEX/GLOSSARY PAGES Click on any of the pages listed below!

|

||

|

Kōgai thru Kushōjin |

||