JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

O thru Ri |

|

|

The molecular model on Lonsdaleite is being used as a marker for new additions from January 1 to May 31, 2021. The piece of sulphur posted at Wikimedia by Rob Lavinsky was used from June 1 thru December 31, 2020.

The detail from the diadem of

the Empress Eugénie |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Obake, Oban, Obi, Obidome, Obijime, Obon, Ochanomizu, Odawara-jōchin, O-fuda, Ōgi, Ohaguro, Ohara Koson, Oikake, Oiran, Ōji, Oke, Okimayu, Okoso-zukin, Ōkubi-e, Okuni, Omamori, Omigoromo, Omiwa, Omiyage, Omocha, Omohan,

Omon-guchi,

Omozukai, Oni,

Onkotogami, Onmyōdō, Onmyōji, Onna budō, Onnadate,

Onnagata, Onoe Kikugorō III,

Onoe Kikugorō V, Onryō, Oranda-tsūji, Orchid (Ran), Orihon, Osaka, Osaka Prints, Oshidori, Oshiguma, Otafuku, Otokodate, Ōtorige, William Perkin, Plum (Ume), Po Chü-i, Port Arthur, Prussian blue, Publisher, Rai, Raijin, Rain & Snow: The Umbrella in Japanese Art, Rakkan, Raku, Rangaku, Ranpeki, Rasetsu, Rasetsukoku, Reikon, Rembrandt, Rembrandt: Experimental Etcher, Rengeza, Rietberg Museum, Rikugei, Rimbō

御化け, 大判, 帯, 帯止め or 帯留, 帯締め, 御盆, 御茶ノ水, 小田原提灯, 御札 扇, お歯黒, 小原古邨, 老懸, 花魁, 桶, 置眉, 大首絵, 阿国, 御守り, 小忌衣, 御神酒徳利口先 (?), お土産, 玩具,

主版, 大門口,

主遣い, 鬼,

陰陽道, 陰陽師, 女武道, 女伊達, 女形,

尾上菊五郎,

蘭, 折本, 大阪, 鴛鴦, 押隈 or 押し隈, お多福 蘭学, 蘭癖, 羅刹, 羅刹国, 霊魂, 男伊達, 大鳥毛, 梅, 白居易, 旅順, 版元, 雷, 雷神, 羅漢, 楽, 蓮華座, 六藝, 輪宝 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

Obake |

御化け おばけ |

A monster, ogre or goblin. According to Kunio Yanagita (柳田 国男), the great modern expert on folklore (1875-1962), obake are different than yurei (幽霊) or ghosts. Obake haunt a particular place while yorei haunt a particular individual. Despite their ominous description obake are said to be more humorous than scary. |

|

Oban |

大判 おおばん |

A woodblock print size generally 15" x 10". This the most commonly encountered size for 19th c. ukiyo prints. |

|

Obi |

帯 おび |

The sash of a kimono and like the word 'torii' obi is a word which has entered our vocabulary. Often used in crossword puzzles. |

|

Obidome |

帯止め or 帯留 おびどめ |

A brooch worn on the obijime.

The image of the modern obidome shown above was posted at commons.wikimedia by 雪割小桜. There are metal rings attached to the back of this piece. The obijime must be threaded through it. |

|

There is an interesting quote from a 1910 'Scientific American: Supplement' article on pearl diving in Japan: ""In the last ten years the Japanese have altered their opinion of pearls. Never in the history of the country has the pearl been more highly prized as an article of feminine adornment than at present. Pearls are used largely in the 'Obidome' or obie fastener, embroidery and the like."

The obidome is also referred to as a pocchiri (ぽっちり).

"There are three main accessories for the obi — the obi-jime (obi braid), obi-dome or pocchiri {obi clasp), and obi-age (obi support). Together they build up an extravagant, multi-layered look for the obi, proclaiming the money and craft that have been put into the artist who wears them. This is of course especially true of the maiko look; geisha tone things down in all aspects of their costume." Quoted from: Geisha: A Unique World of Tradition, Elegance and Art by John Gallagher, p. 218. |

||

|

|

||

|

Obijime |

帯締め おびじめ |

A decorative cord used to hold an obi in place. Traditionally these cords were made of silk.

|

|

Obon |

御盆 おぼん |

A Buddhist celebration during which the deceased are said to visit the homes of their relatives for several days. |

|

Lanterns are hung to guide them home. Food is set for them and at the end lanterns are placed in rivers, lakes, ponds, etc. to aid the souls of the deceased to return to the netherworld. It is celebrated in some areas as early as mid-July and as late as mid-August in others. There are also regional variations in the practice of this event.

Often the spirits of the dead are accompanied by other more vengeful, uninvited spirits which have returned to wreak havoc and vengeance. Because of that the Obon dance is performed in an attempt to scare off the malicious spirits.

Celebrated as early as 657 this festival may have its roots in Zoroastrianism in Persia combined with Buddhist practices. Some sources say that the Buddhist monk Mokuren (もくれん) saw a vision of his deceased mother starving in hell and he offered her a bowl of rice. That was around July 15th and hence its origin and timing. |

||

|

|

||

|

Ochanomizu |

御茶ノ水 おちゃのみず |

A district of Edo/Tokyo 1 |

|

Odawara-jōchin |

小田原提灯

おだわらぢょうちん |

"The cylindrical chochin (in which the paper-covered spiraling bamboo shade collapses into the wooden end caps) were associated with the region of Odawara in particular, and to this day bear its name, Odawara-jochin." Quoted from: Bamboo in Japan by Nancy Moore Bess and Bibi Wein, p. 121.

We found both of these examples at Pinterest. The one with the rabbit was posted there by Christine Davis and the one above was placed there after being posted at Nippon-Nippon at tumblr. |

|

O-fuda |

御札

おふだ |

A protective charm. Note the wooden plaques strung together on a cord hanging around the figure's neck. 1

"Fuda are generally made of a flat piece of wood often both slightly pointed and broader at the top than at the bottom, on which an inscription of some sort, often the names of the shrine temple and its kami/Buddha, has been written in cursive brush strokes. They are generally also wrapped in white paper so that the inscription is visible and are tied with a bow of colored string. They are of various sizes." The larger ones are considered more efficacious. "The Kōrien-Narita-san temple... has a whole array of fuda for traffic safety (the primary riyaku [benefit: 利益] associated with the temple), up to approximately a metre in height: the prices vary accordingly. Another common type of fuda is a piece of paper on which an image (usually of Buddha), often accompanied by a sacred inscription, has been imprinted."

Source and quotes from: Religion in Contemporary Japan, by Ian Reader, University of Hawaii Press, 1991, p. 176.

"Basically fuda sacralise an area: once acquired they are placed in, for example, the butsudan [household Buddhist shrine: 仏壇] or kamidana [small Shintō shrine or shelf: 神棚] or elsewhere in the house from whence they protect the environment and surrounding." These protective symbols appear on trains and ferries, too. "Similarly I have a paper fuda depicting Fudō, given to me by a priest in Shodōshima: I was, he told me, to place it in the hallway of my house facing the door, and this would keep the house safe from burglars and other miscreants." (Ibid., p. 177)

See our entry on Fudō Myōō.

To the left is a detail from a cropped photo of an O-fuda stand. It was placed in the public domain by Tomomarusan at http://commons.wikimedia.org/. |

|

Ian Reader points out that "At Narita-san, for example, fuda and o-mamori are placed before the image of Fudō... and, through rituals performed by priests, Fudō's power and spirit passes into the talismans and amulets. They are sacrilised, no longer wood and paper but actually Fudō himself." (Ibid.)

Lafcadio Hearn tells us that "Homes are protected from evil spirits by holy texts and charms. In any Japanese village, or any city by-street, you can see these texts when the sliding-doors are closed at night: they are not visible by day, when the sliding doors have been pushed back into the tobukuro [戸袋]. Such texts are called o-fuda (august scripts): they are written in Chinese characters upon strips of white paper, which are attached to the door with rice paste: and there are many kinds of them. Some are texts selected from sutras... Some are texts from dhâranîs - which are magical. Some are invocations only, indicating the Buddhist sect of the household... or little prints, pasted above or beside windows or apertures - some being names of Shintō gods; others symbolical pictures only, or pictures of Buddhas or Bodhisattvas. All are holy charms - o-fuda: they protect the houses; and no goblin or ghost can enter by night into a dwelling so protected, unless the o-fuda be removed. [¶] Vengeful ghosts cannot themselves remove an o-fuda; but they will endeavor by threats or promises or bribes to make some person remove it for them."

Quoted from: The Writings of Lafcadio Hearn, Houghton Mifflin, 1922, pp. 283-4. |

||

|

|

||

|

Ōgi |

扇

おうぎ |

A folding fan: The image to the left is only one of the motifs used for a family crest or mon. However, in this case it could also be used as a butterfly mon. This shows the level of creativity of the Japanese sense of design. |

|

In 1960 U. A. Casal in his "Lore of the Japanese Fan" published in the Monumenta Nipponica (p. 61) gave a reasonable explanation for why the Japanese never warmed to the feather fan like we did in the West and elsewhere. "...the feather-fan was never greatly developed in Japan. It would not be surprising if this were partly due to its connection with the killing of birds. Not only was killing contrary to all Buddhist tenets, and at times rigorously forbidden in whatever form, but anything dead was also taboo in Shintō."

Editorial note: While this information may seem obvious to you, it was an 'A-ha, I get it!' moment for me.

Ōgi are also called sensu (扇子). The folding fan can also be called a suehiro (末広).

The word ōgi has its origin in afugi (あふぎ) or "something which creates wind." This was its early pronunciation.

This is so Marx Brothers: "It is a recorded historical fact that Fujiwara Tadahira [藤氏忠平], who lived from A.D. 880 to 949 and gained a high reputation as an aesthete and dilettante, had a cuckoo painted on his fan, which he never opened without first without imitating the cry of the bird." (Casal - p. 75)

There is a legend that the Emperor Gosanjō (1069-1073: 後三条) was a very frugal man. He owned and loved a hi-ōgi (檜扇) or fan made of wood slats. As it aged and cracked he pasted paper onto it and the modern folding fan was born. (C. - 76)

In footnote 49 on page 95 "In the Orient it is considered highly impolite to breathe into another's face. The Buddha forbade garlic and other pungent herbs. It is possibly due to this belief in the breath's impurity that the underling has to kowtow when speaking to the lord: his breath is directed towards the ground and will not affect the atmosphere. Often the Oriental will hold his hand or his fan over the mouth when speaking..." Personally I wish this was done a little more in the West.

Another rule of etiquette was used when passing items from one person to another: "It being impolite, generally speaking, to pass a thing from hand to hand, a fan may serve as a tray, either to proffer or to receive. Begging monks never took alms except on a partly opened fan. (To open it completely would have looked greedy.) (C. - 95) In "The Tale of Genji" the prince is handed a delicate flower this way presented on a highly perfumed white fan.

"The Japanese actor, whether of the No or Kabuki stage, could not exist without a fan. With an incredibly calm mimic, wielding his fan he can "outline" any kind of object, suggest the thatched roofs of a village, the floating of a boat, the rising of smoke or the pouring of a liquid, even the appearance of some supernatural, weird being. By the clever manipulation of his fan, he can underscore his pensiveness, sorrow, jollity, or drunkenness." (C. - 96)

Casal argues (p. 101) that fans were carried in the winter too because of

their ancient linkage to function as a tool which could dispel evil spirits.

That is also the reason why all guests at weddings carried them. "For

At the name giving ceremony a prominent relative who would be comparable to our 'godfather' would present a baby boy with two ōgi representative of the two swords carried by the samurai which in their turn stand for "courage and endurance." (C. 101-2)

Every year the Emperor is presented with a special fan referred to as 'a humble thing' or kenjō (献上). The front shows a flowering plant while the back is a plain black sprinkled with silver. (C. - 102)

Whenever a person would set out on a long journey friends would present the traveler with a fan with valedictory sayings painted on it. (C. - 103)

"In the early days of the telegraph in Japan, when poles and wires were full of hidden menaces to the natives, many of them would not willingly pass under the overhanging danger. If unavoidable, they would screen themselves against the diabolical wires by opening the fan and holding it over the head." (Ibid.) Is this so different from the controversy in modern society about living too close to power lines? |

||

|

|

||

|

Ohaguro |

お歯黒

おはぐろ

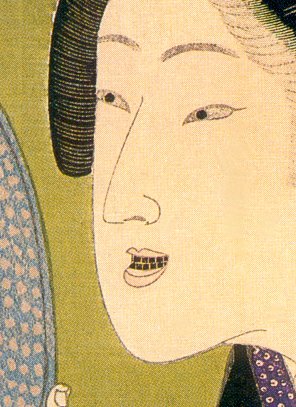

|

Tooth blackening: An ancient practice going back to the Heian period, i.e., 9th century, whereby women mainly stained their teeth black. The dye was made from a mixture of oxidized "...iron shavings melted in vinegar and powdered gallnuts." During the Muromachi period (1336-1568) this practice gained popularity among the lower classes and "...was done from the age of puberty. In the Edo period (1603-1868), married women were required to dye their teeth black."

Quoted from: Dictionary of Japanese Culture by Setsuko Kojima and Gene A. Crane, p. 253.

The powder was often applied using a split-bamboo toothbrush.

(See also nurude.)

John Stevenson in Yoshitoshi's Women: The Woodblock Print Series "Fuzoku Sanjuniso" (Avery Press, 1986, p. 34) notes: "Blackened teeth were considered beautiful, possibly because teeth were a visible part of the skeleton, which as a symbol of death was unclean. Though teeth-blackening was the special mark of married women, courtesans also used it as a sign of adulthood. It formed part of the ceremony held for the debut of a trainee courtesan when she became a shinzo at the age of about fourteen."

See also our entry on nurude on our Mom thru N index/glossary page to see an image of sumac galls used in the making of this product. |

|

In The World of the Shining Prince: Court Life in Ancient Japan (pp. 203-4) Ivan Morris discusses several of standards used to judge beauty such as pale skin. The higher the rank the whiter the skin color had to be even if that meant applying layers of powder. "Heian women observed two customs that, attractive as they no doubt were to the gentlemen of the time, would hardly add to their appeal for Western men, or indeed for most modern Japanese. They plucked their eyebrows and then carefully painted in a curious blot-like set, either in the same place or about an inch above. They also went to the greatest trouble to blacken their teeth with a type of dye usually made by soaking iron and powdered gallnut in vinegar or tea. During later centuries this bizarre custom spread throughout the country and came to denote a woman's married status; in Heian times it was restricted t the upper classes, but not to married women."

Morris added a reference about the eccentric heroine of "The Lady Who Loved Insects". She refused to shave her eyebrows or blacken her teeth and this disgusted both her attendants and a potential suitor. "'Ugh!' said one of her maids. 'Those eyebrows of hers! Like hairy caterpillars, aren't they. And her teeth! They look just like peeled caterpillars.' A certain Captain of the Guards, who has been interested in the girl, is put off by her dark, thick eyebrows, which give her face an unpleasing boldness, and particularly by her unblackened teeth, which gleam horribly when she smiles.'" (p. 204)

In a footnote Morris notes that during the Han dynasty in China women plucked or shaved their eyebrows. However, tooth blackening appears to have been practiced only in Japan. Van Gulik argued that this fashion statement may have originated in the South Seas.

In a second footnote Morris states: "In the Tokugawa period, courtesans, who were know as 'brides of the night', also blackened their teeth."

In the Safflower chapter of The Tale of Genji the prince has returned to "His young Murasaki.... In deference to her grandmother's old-fashioned manners her teeth had not yet received any blacking, but he had had her made up, and the sharp line of her [applied] eyebrows was very attractive."

Quote from: The Tale of Genji, by Murasaki Shikibu, translated by Royall Tyler, Viking Press, 2001, vol. 1, p. 130.

The mixture used for tooth blackening was referred to as hagurome (歯黒め).

In Act 2: Scene 3 of the Tokaido Yotsuy kaidan Oiwa looks in the mirror and sees the results of the poison which her husband has given her. Despite her horrific disfigurement she prepares to go out. "Bring me my tooth blackening" she demands. Takuetsu, a masseur in the employ of her husband, argues against this: "But you are still sick and weak. You've just given birth. It's not safe for you to go out." She insists. Then it is noted that "She rinses her mouth, wipes her teeth dry, and then sits down in the center of the room. She rinses her mouth, wipes her teeth dry, and then applies the blackening.... She messily covers the corners of her mouth, which makes it look as though her mouth is monstrously wide."

Source and quotes from: Traditional Japanese Theater: An Anthology of Plays, edited by Karen Brazell, translation and commentary by Mark Oshima, Columbia University Press, 1998, p. 477.

Staining the teeth is not unique to the Japanese. In The Kama Sutra of Vatsayayana by Sir Richard Burton women are praised for having good teeth capable of being stained - a positive cosmetic feature. Tattooing is also mentioned.

In A Brief History of the Smile by Angus Trumble (published by Basic Books in 2004, pp. 63-5) notes that the Achual tribe of the Amazon basin still practice tooth staining their teeth. About the Japanese practice Trumble says: "According to one school of thought, ohaguro originated in the Buddhist idea that white teeth reveal the animal nature of men and women and that the civilized person should conceal them, if by no other means than beneath a coating of black dye." Or, the author speculates, that the samurai class had their wives and daughters stain their teeth black to make them less desirable for rape or abduction. Trumble adds "That many sources agree that the practice was also thought to protect against tooth decay..." "Well before the twelfth century, tooth-blackening marked a girl's coming of age. So did okimayu [置眉], the practice of shaving off her eyebrows and substituting painted ones..." Even some early noblemen and samurai began blackening their teeth. "One warrior, upon removing the helmet of a slain nobleman, found his opponent to be a boy of sixteen, his face powdered, his teeth elegantly blackened." Later it was only women, again, who stained their teeth intentionally. By the 18th century it was almost universal. By the 19th it came to be used only by married women.

Basil Hall Chamberlain gives a recipe for tooth blackening in his Things Japanese (pp. 63-64) quotes A. B. Mitford from his Tales of Old Japan who in turn was quoting an Edo druggist: "Take three pints of water, and, having warmed it, add half a teacup full of wine [i.e., sake]. Put into this mixture a quantity of red-hot iron; allow it to stand for five or six days, when there will be a scum on top of the mixture, which then should be poured into a small teacup and placed near a fire. When it is warm, powdered gall-nuts and iron filings should be added to it, and the whole should be warmed again. The liquid is then painted on to the teeth by means of a soft feather brush, with more powdered gall-nuts and iron, and after several applications, the desired colour will be obtained."

Wang Bao (王褒), a 1st century B.C. Chinese author, "... writes that there are countries whose people braid their hair, scar their faces, [and] blacken their teeth..." Wang was not writing about the Japanese, but about others from extreme southern China and from Southeast Asia. It is known that tooth blackening was a common cultural practice among many different groups and was even common on certain Pacific islands. This proves how old tooth blackening is. Perhaps the Japanese were also aware of such practices.

Quote from: "Tattoo in Early China, by Carrie Reed", Journal of the American Oriental Society, vol. 120, No. 3, Jul. - Sep. 2000, p. 363.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Ohara Koson |

小原古邨 おはらこそん |

Artist 1877-1945 1 |

|

Oikake |

老懸

おいかけ

|

As I have mentioned elsewhere, if you live long enough, you will find there is a word for everything - sometimes two - sometimes more -generally more. Well, that is the case with oikake - those, unusual to the Western eyes on first glance, side-flaps to the courtly headdress. ¶ In The Japanese Theatre by Benito Ortolani (pp. 17-18) describes an ancient type of Shinto music and dance, a mikagura (御神楽), performed specifically for the emperor. It is still performed today, albeit in a shortened form. In the first part, the niwabi (庭燎) "...Within the compound of the imperial palace in front of the shrine dedicated to the goddess Amaterasu... where the sacred mirror is kept, a garden fire (niwabi) was lit. The director of the performance (ninjo) [the chief kagura dancer: 人長] first entered into the dancing area, which was covered with straw mats and which was situated in front of the fire. At the sides sat about seven musicians and fifteen or sixteen singers... ¶ [The ninjo] is considered to be the successor to god Futotama in Uzume's myth, who had the task of organizing and directing the ritual perfomances, and of speaking the words of conjuration and summoning. The ninjo role was performed by a member of the imperial guard, costumed as a noble warrior of the Heian period, with its special court hat (kammuri) and feather-like eye-protections (oikake) at the sides, which had the function of keeping the dust from the warrior's eyes."

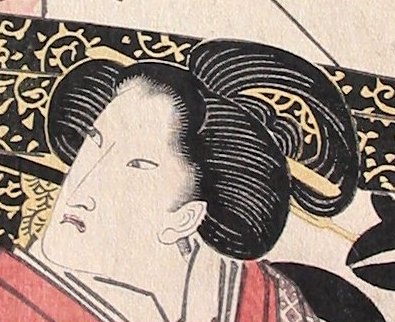

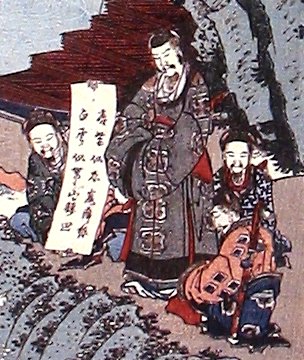

The two images to the left are by Shunshi and actually come from different versions of the same image. The detail above is from a Shunko print representing one of the Six Great Poets. |

|

Oiran |

花魁 おいらん |

Highest order of courtesan 1 |

|

Ōji |

王子 おうじ |

This is not only the word for prince, but it also describes a type of kabuki wig. "An even more exaggerated form of male hairstyle with a large bushy growth on top and voluminous side locks that hang down over the chest is the ōji, or 'prince' wig, worn frequently by villainous lords in jidaimono." Quoted from: A Guide to the Japanese Stage: From Traditional to Cutting Edge by Cavaye, Griffith and Senda, p. 75. |

|

Oiran dōchū |

花魁道中

おいらんどうちゅう

|

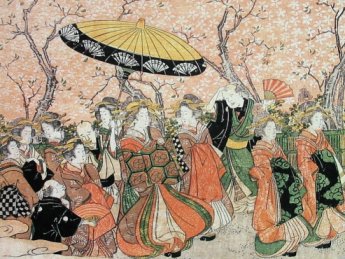

A grand procession of courtesans: "Originally the word dōchū described the ceremonial processsion made by the shogun's officials between the cities of Kyoto and Edo. Since the Yoshiwara had streets named Edo and Kyoto, the procession of a courtesan to an ageya or a teahouse was likened to that of a grand daimyō."

Quote from: Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan, by Cecilia Segawa Seigle, University of Hawaii Press, 1993, p. 225.

Seigle adds: "...the procession of a leading oiran on the most formal occasion consisted of some twenty or twenty-one persons."

Ibid.

J. E. De Becker in his Yoshiwara: The Nightless City (p. 34) stated: "In the old days the tea-houses in Ageya-machi were allowed to contruct balconies on the second stories of their establishements for the convenience of those guests who desired to witness the procession of courtesan (Yūjo-no-dō-chū) that formed one of the most interesting features in the life of the Yoshiwara."

"The high-ranking courtesans all have male attendants, who hold parasols over them and their teenage shinzō (protégés). The girls are kamuro (attendants). The parasols are used here as symbolic markers of status rather than serving any practical function."

Quote from: The Women of the Pleasure Quarter: Japanese Paintings and Prints of the Floating World, by Elizabeth de Sabato Swinton, et al., Hudson Hill Press, 1996, p. 54.

The top example to the left is a detail from a print by Eizan. The one at the bottom is from a Yoshitoshi print and is here taken out of context, but is being used to help convey the concept. |

|

Oke |

桶

おけ |

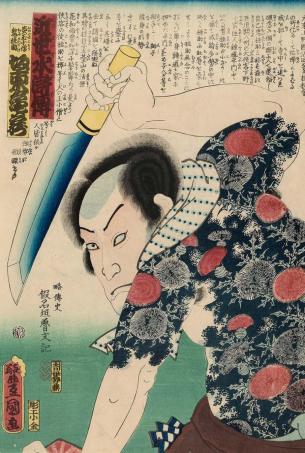

Bucket: The image to the left shows a detail from a print by Kuniyoshi where Danshichi Kurobei is washing off the blood of his father-in-law whom he has just slain. This image was sent to us courtesy of E. Thanks E!) |

|

Okimayu |

置眉

おきまゆ |

Shaving the eyebrows and replacing them with false one higher up the forehead: "Well before the twelfth century, tooth-blackening marked a girl's coming of age. So did okimayu, the practice of shaving off her eyebrows and substituting painted ones; konezumi [こねずみ?], a mixture of lampblack, rouge, gold leaf, and sesame oil was occasionally used, but there were plenty of other recipes and a variety of brushes and spatulas with which to apply the gooey makeup. At first these 'adult' cosmetic procedures were adopted by girls of thirteen, but eventually, in the nineteenth century, the acceptable age climbed to seventeen."

Quoted from: A Brief History of the Smile, by Angus Trumble, published by Basic Books, 2004, p. 65

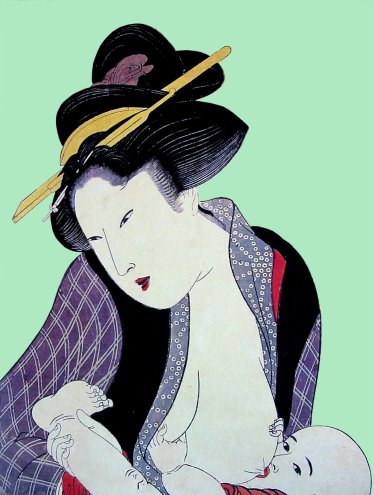

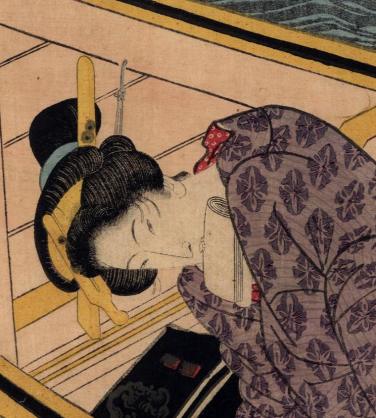

The above image with the moth eyebrows is from a detail of a Yoshitoshi print.

"By the eighteenth century... the shaving of eyebrows was only done by brides, or by mothers following the arrivals of their first-born child." (Ibid.)

The image to the left of a mother breast feeding is a detail from an Utamaro print. Notice her lightly printed areas where her eyebrows have been shaved off. |

|

Okoso-zukin |

お高祖頭巾

おこそずきん |

A scarf or kerchief formerly worn by women during cold and/or inclement weather. In a bitter, frigid wind only the eyes were left visible. Clearly the okoso-zukin could be adjusted to meet the conditions.

As you may have noticed there seems to be a specialized word or phrase for just about everything. Take as an example this garment. I had seen it in prints by Kiyonaga, Utamaro, Eisen and Kunisada among others, however it wasn't until recently that I found a specific reference naming it. What I can't be sure of is the color. Most frequently it is black, but sometimes I think it could be white too. And what about similar coverings worn by men? Are those also referred to as okoso-zukin?

A thought: I don't know about you, but just knowing the name of something somehow helps me understand the milieu in which it existed. That is one of the purposes of this list of index/glossary pages. Yet there is so much more to discover. It is never ending. The tip of the iceberg. |

|

Ōkubi-e |

大首絵

おくびえ |

Large portrait head 1 |

|

Okuni (aka Izumo no Okuni) |

阿国 おくに |

Okuni, the mythic or real figure, is credited with the origin of what we now call kabuki theater. It began at the end of a turbulent era of wars and deadly rivalries. "In the wake of this new era public tastes, legend has it that Okuni, a priestess of the great Izumo no Ōyashiro Shrine in central Izumo Province (now Shimane Prefecture), journeyed across the mountains to not-so-distant Kyoto, ostensibly to obtain contributions for the maintenance of the shrine through performances of a prayer-dance. This dance, the nembutsu-odori (literally 'dance of prayer to Buddha') was an outgrowth of five centuries of teaching prior to Okuni by such priests as Kūya, Ippen, and during Okuni's time by the priest Hōsai, who believed that the principles of Buddha could be most easily understood not by difficult or tedious preaching but by plunging into ecstasy through song and dance. Later the nembutsu-odori became familiar as a folk dance. ¶ Okuni's arrival in Kyoto about 1600 is considered a historical event in the annals of popular theater in Japan, for it presaged the beginning of various theatrical forms which gradually evolved into the present-day Kabuki. ¶ Okuni belonged to a class of young maidens known as miko or shrine virgins, albeit of questionable virginity, who served the gods of the Shintō shrines, danced before them, and made themselves generally available for any menial task. Since people from all walks of life visited the shrines, inevitably bawdyhouses abounded in their vicinity. The miko often performed in these houses after dancing for the gods." Quoted from: Kabuki Costume by Ruth M. Shaver, p. 34.

To the left is an image from a composition designed by Hokushū from 1821. It is his theatrical interpretation of what Izumo no Okuni might have looked like - at least as portrayed in a contemporary kabuki play. Click on the image to see the full image at the Lyon Collection. |

|

"Upon reaching Kyoto, Okuni proceeded to a dry place in the bed of the Kamo River, since it was there that low-class entertainers could perform without being taxed, and the space was free for the asking. At the foot of Gojō Bridge she made use of a koyagake butai (outdoor stage) for her performances. This type of temporarily built open stage - made of logs, bunting, and matting - can be seen today at circuses and shrine festivals. The word koyagake itself is a very old and popular expression meaning 'hut-styled' or 'temporarily built.' " (Ibid., p. 35)

"Only by examining old painting can we envisage the costumes worn by Okuni. When presenting her first dance inKyoto, she is thought to have appeared in a priest's black silk robe over an ordinary kimono, both ankle-length. A nurigasa (nuri, painted; kasa, hat; that is, a lacquer-coated, umbrella-shaped hat) covered her head, while around her neck was hung a scarlet breast-length strap of karaori (brocaded silk) on which was fastened a kane (small metal gong). Okuni struck the kane with a wooden hammer called a shumoku as she sang the well-known tunes of the day and danced in a most enticing manner." (Ibid.)

"Many, if not all, of the events surrounding the story of Okuni's life are based on legend. Documentation fails to record accurately where fiction ends and truth begins. So be it what it may, fate stepped into Okuni's life int he form of a handsome man-about-town, Nagoya Sanzaburō, who undoubtedly had been drawn to Okuni by her physical charms and daring exhibitionism." (Ibid.)

Earl Roy Milner in The Princeton Companion to Classical Japanese Literature (p. 64) gives a slightly different take on the role of Okuni for the start of kabuki theater. "In this initial period we search in vain for great plays. And yet from 1610 or 1615 puppets begin to be used in the theater. Moreover, at the beginning of the period Kyoto saw the rise of both male and female players. Of the female the most famous is the troupe, or rather troupes, that went under the name of 'Okuni Kabuki.' The new government's attitude toward women did not help, for although various kinds of female performers were crucial to the development of the drama that followed, the female troupes in Kyoto were effectively quelled by a government that passed edicts in the name of morality. Young male troupes were interdicted on similar grounds, but the times favored adult males."

"We now know that the 'Okuni kabuki' of actresses does not have the priority once thought. The belief that they were first has a certain appropriateness in the fact that women had long been shamans and had performed (as miko) in Shinto rites. Moreover, from Kamakura times and following there had been performers such as the shirabyoshi. It now seems that 'Okuni' is a role or player title such as 'Danjūrō.' In any event, Okuni kabuki has no priority over that of male actors or, for that matter, over jōruri." (Ibid., p. 70)

Miner dates the first kabuki performances by "Okuni" as from ca. 1597. In another entry he gives the first date as 1603.

There is a lot of discussion of promiscuous sexuality in reference to Okuni. Louis Crompton deals with that topic directly in Homosexuality and Civilization on p. 425: "The origins of kabuki were, if anything, even less respectable than Nō. In 1603, in a dry riverbed in Kyoto, a temple attendant named Okuni performed dances whose appeal was more sexual than religious. An immediate sensation, she organized a troupe of women whose performances advertised their availability as after-hours prostitutes. women whose performances advertised their availability as after-hours prostitutes. Quarrels broke out over the women, and in 1629 the government banned the so-called women's kabuki, a term that signified 'eccentric' or 'off-beat' and carried a hint of titillating improprieties. It was replaced by the boy's kabuki, in which boys in their early teens played the roles of both sexes and were, like their predecessors, on call for private intimacies."

Okuni teamed up with her mentor/lover Nagoya Sanzaburō. She dressed as a man and he as a woman for their performances. "To her Japanese audience with its jaded appetite, Okuni's entertainment was welcome and stimulating. Okuni hastened to capitalize on her popularity by collecting the entrance fees for the dance performances and fees from the eager patrons for her troupe's after-hours profession, prostitution. The shine's needs were forgotten." (Shaver, p. 36) |

||

|

|

||

|

O-mamori |

御守り

おまもり |

An amulet or charm: "O-mamori are smaller [than fuda], usually consisting of a small brocade bad or sachet with draw strings. On the bag are written the shrine or temple name and the particular riyaku [benefit] it is for. Inside the bag there is usually a piece of paper or wood with a further inscription such as the text of the Hannya Shingyō [the Heart Sutra]. Like much else in the world of Japanese religion, styles may change to reflect the contemporary mood: in the 1980s plastic o-mamori shaped like credit cards (and indicative of Japan's growing development of plastic money) have come into prominence. Many shrines and temples now provide, besides the more traditonal o-mamori, some in the form of a credit card." Some o-mamori double as phone cards, but always with religious inscriptions and blessings. Now one is not only protected by a talisman or amulet, but one can also make a phone call. [How convenient.]

Source and quotes from: Religion in Contemporary Japan, by Ian Reader, University of Hawaii Press, 1991, pp. 176-7.

See our entry on o-fuda above.

O-mamori are more personal than fuda since they are meant to protect only the possessor and not the whole area. Some can be worn while other, the kind that function as both talisman and phone card, can be carried in a wallet. Children carry them on their school satchels while drivers may hang them [like fuzzy dice] in their cars [or I suppose like little statues of Jesus or Mary mounted on the dashboard]. (Ibid., p. 177)

The image to the left is by Rama who placed it in the public domain at http://commons.wikimedia.org/. |

|

Omigoromo |

小忌衣

おみごろも |

Samuel L. Leiter wrote: "A kabuki costume, unknown off the stage, consisting of a long, trailing, haori-like brocade over-robe with a high, standing tuxedo collar, whose pattern and fabric contrast with that of the garment's main part. Jidai mono lords, nobles, and generals wear it. At the front is a thick, knotted, and tasseled golden cord, loosely holding the robe together. The accompanying kimono is of white silk with a padded, front-tied obi Some characters also wear trailing hakama (nagabakama) or baggy sashinuki. It is seen, for example, on Yoshitsune in Yoshitsune Senbon Zakura."

While Leiter may have only been focused on the kabuki stage there was another use of the omigoromo. However, in his defense, that omigoromo is not styled the same way.

" ‘‘ Omigoromo” is a kind of ceremonial jacket used for the Shinto rites at the Imperial Court since the reign of Emperor Saga (Konin period;809−823)and now it is only used in ‘‘Daijousai” festival, where the Emperor worships his ancestors with newly −cropped rice in the first year of his enthronement.“Omigoromo” were incinerated after the ceremony, so it is rare to find any extant these days" Quoted from: Characterization of the “Omigoromo ” Stored by Showa Women’s University

The image to the left is from the collection of the Tokyo National Museum. It dates from the 19th century. |

|

Omikidokkuri no kuchisashi |

御神酒徳利口先 (?) おみきどくりのくちさし |

Omiki is sacred wine

or saké. In The Writings of Lafcadio Hearn (Houghton Mifflin Company,

1922, pp. 72-73) the author writes

"The most curious objects to be

seen on any ordinary kamidana are the stoppers of saké-vessels or o-mikidokkuri

('honorable saké-jars'). These stoppers - o-mikidokuri-no-kuchisashi - may

be made of brass, or of fine thin slips of wood jointed and bent into the

singular form required. Properly speaking, the thing is not a real stopper,

in spite of its name; its lower part does not fill the mouth of the jar at

all: it simply hangs in the orifice like a leaf put there stem downwards. I

find it difficult to learn its history [a problem this writer often faces];

but, though there are many designs of it - the finer ones being of brass -

the shape of all seems to hint at a Buddhist origin. Possibly the shape was

borrowed from a Buddhist symbol - the Hoshi-no-tama, that mystic gem whose

lambent glow (iconographically suggested as a playing of flame) is the

emblem of Pure Essence..." Tokkuri is a saké bottle with an elongated mouth. During certain Shinto ceremonies a special white porcelain container is used like the one shown to the left. Drinking the saké at this time is meant to link the participant with the gods.

The (?) to the left above means I haven't the slightest what characters to use - especially the 口先. It was a guess on my part since I was unable to find the exact term. |

|

Omiwa |

おみは

|

Omiwa is the main female character in the play Imoseyama Onna Teiken (妹背山婦女庭訓). She can often be identified by the spool of thread she holds.

The image to the left is from the Lyon Collection. To see more about this print click on the image. |

|

Omiyage |

お土産 おみやげ |

Souvenir - Japanese woodblock prints were often produced to act as souvenirs of famous or scenic places or of actors in kabuki performances. |

|

Omocha |

玩具 おもち |

Toys: Now understood as toys, but traditionally these were not viewed the same way. Formerly they were considered as talismans or amulets. According to Josef Kyburz in his Omocha: Things to Play (or not to Play) With states that the word 'omocha' may have made it first appearance in a comic novel, The Bathhouse of the Floating World or Ukiyoburo (浮世風呂) by Sanba Shikitei (三馬式亭: 1776-1822) in 1809. However, in this case the plaything is another human being toyed with. That does not mean that there were not toys prior to that, but that they were referred to differently. For example, there were hobbyhorses and tops which were mentioned as early as 937. ¶ Still the term 'omocha' did not catch on quickly as meaning a toy. "It was only towards the very end of the Meiji era (1868-1912) that the word omocha, born of popular Edo idiom, came into common usage, and it was later still, in the 1930s, that it was definitely established in the written language as the standard generic term. The alternative gangu 玩具 appeared in the first years of the Taishō era but has remained to this day a learned word, originally created by toy collectors using a high-sounding Sino-Japanese pronunciation for asobigu 遊具 [referring to something to play with]... Gangu [an alternate pronunciation of omocha] was coined and adopted as a taxonomic concept in reaction to the influx of Western playthings, when it became evident that the latter had already driven traditional Japanese toys from the child's world, at least in urban society." Yet the author still makes distinctions between the two variant readings: the first, omocha, is closer to a toy while gangu is more of a plaything. (Kyburz, p. 3) |

|

So what is an omocha? Kyburz sites the work of Frederick Starr who delivered a paper in 1926 to the Asiatic Society of Japan. Starr lists four categories: 1) Real toys made for play; 2) "...objects, more or less intended for children's pleasure, but somewhat related to temples or shrines..."; 3) religious objects sold by temples and shrines which look like toys but possessing protective powers and never made for play; and 4) ema or votive plaques. This last category may seem a bit odd except Kyburz clears it up in a footnote: "Ema were until at least Starr's time an integral part of all Japanese omocha collections, and have remained so in some much more recent ones." Yanagita offered a different list and left votive plaques off altogether. |

||

|

|

||

|

Omohan |

主版 おもはん |

The omohan is the key block from which all of the black line prints are pulled. Generally there is one line print for each color (or area) of the finished product. Then separate blocks are carved based on the images printed from the omohan. |

|

Ōmon-guchi |

大門口

おおもんぐち |

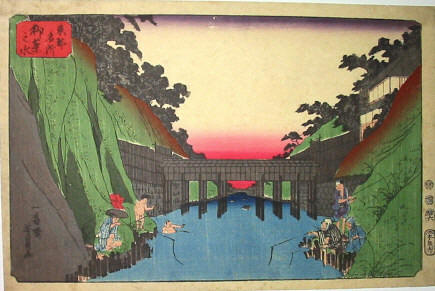

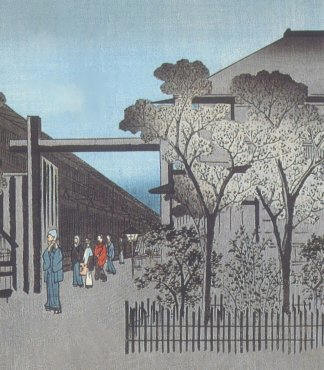

The entry gate into the Yoshiwara red-light district. The image to the left is a detail from an 1858 Hiroshige print showing clients leaving the Yoshiwara through the Omon Gate at dawn. |

|

Omozukai |

主遣い おもづかい |

The chief bunraku puppeteer who controls the head and right arm. It takes decades of hard work and training to attain this level. Today the greatest masters are name Living National Treasures. In an article from the Japan Times from 2003 it notes that Kiritake Kanjurō III apprenticed for 15 years just to handle the legs or ashi (脚), another 10 years working the left hand or hidari (左).

The image to the left is of a print by Sekino Jun'ichiro from the Lyon Collection. To see more about this print click on the image. |

|

Oni |

鬼

おに |

A demon, devil, ogre or evil spirit. (In Japan in the game of tag when touched the person is not told you're 'it', but is called the 'oni'.) In hell it is red and blue oni which torment the dead.

"Oni were customarily portrayed with one or more horns protruding from their scalps. They sometimes had a third eye in the center of their foreheads, and varying skin colors, most commonly black, red, blue, or yellow. More often than not, the oni were scantly clad, carryed [sic] an iron mace, and wore a loincloth of fresh tiger skin. Though oni were not exclusively male, for there were female oni, the popular image of oni was predominantly that of a male character."

Detail from a Kuniyoshi print of two demons being driven away when beans are thrown at them. |

|

Oni are capable of changing shapes. They can take the forms of either human males or females at will. The historic hero Raikō once noted that "Oni are transformers — if they learn that punitive force is coming, they will turn into dust and leaves, and it will be hard for us ordinary humans to find them."

These demons can also cause natural disasters or possess household objects.

Babies born with teeth were thought to be the children of oni and were often put to death.

Oni are often associated with lightning an thunder.

"...oni are not exclusively evil beings. An oni can also be a supernatural entity that brings good fortune and wealth."

During Setsubun (節分) is a holiday at the end of winter. "Traditionally, on the night of setsubun, people scatter beans, one for each of their years, saying “oni wa soto, fuku wa uchi”... (Demons out, Fortune in). In some rites, a male member of the community pretending to be an oni (wearing a paper oni mask) enters a house, but is chased outside while people scatter their beans."

Yamaoka Genrin (山岡元隣: 1631–1672), "...a widely recognized intellectual of the day..." claimed that yang was the work of kami and yin that of oni.

All of the information and quotes but the very first comment at the top of this entry on oni has come from a paper entitled 'Transformation of the Oni' is by Noriko Reider and was published in the Asian Folklore Studies, Volume 62, 2003: 133–157.

"It is difficult to translate the term oni because an oni is a being with many facets. It may be imagined as some ambiguous demon, or it may be impersonated as an ugly and frightening humanlike figure, an ogre. However, it is not an intrinsically evil creature of the kind, like the devil, who, in monotheistic religions, is the personification of everything that is evil. The difficulty in describing oni, is in itself, it seems to me, part of the oni's character as a basically elusive and ambiguous creature. At setsubun, when people throw beans to dispel the oni, they do it with so much fun so that the onlooker may get the impression that an oni is nothing more than a character from children's stories." Quoted from the foreword to Japanese Demon Lore: Oni from Ancient Times to the Present.) |

||

|

|

||

|

|

鬼薊

おにあざみ

|

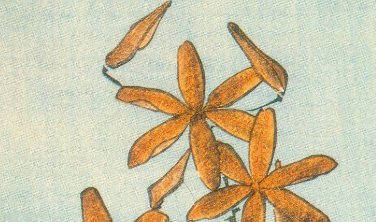

A thistle of the aster family (Cirsium borealinipponense): Botanic.jp says "It is a perennial herb that is endemic to Japan and distributed northward form Chubu district to the Japan Sea side of Touhoku district. This herb grows in montane to sub-alpine grasslands and can reach 50-100 cm in height."

Literally it could be translated as 'devil thistle'.

Photo of a flowering oni-azami at the botanical site run by Shu Suehiro.

The images to the left are from a Toyokuni III print in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The top one shows the entire print from 1862 and below that is a detail of the tattoo on the figures back. |

|

Oni no nenbutsu |

鬼の念仏

おにのねんぶつ |

Noriko Reider wrote in Japanese Demon Lore: Oni from Ancient Times to the Present: "The most well-loved figure in the entire Ōtsu-e repertoire is called oni no nenbutsu (oni intoning the name of the Buddha), which depicts a praying oni dressed in the Buddhist priest's garb with a gong around his neck, a striker in one hand and a Buddhist subscription list on the other. As McArthur comments, an oni as a a Buddhist priest seems contradictory, for the oni who is considered to be evil strives for Buddhahood itself. Some of the “inscription to the paintings warns against superficial appearance of goodness, while others suggest that even the most evil beings can be saved by Buddhism... The depicted image of an oni in Buddhist garb is quite humorous and friendly. Ōtsu town is one of the fifty-three stations of Tōkaidō (Eastern Sea Route) connecting Edo and Kyoto. Undoubtedly, the praying oni were popular souvenirs for the traveler who journeyed on to Tōkaidō. As Juliann Wolfgram notes,

The image to the left is an ōtsu-e painting of a "Demon Intoning the Name of Buddha" is from the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art. It dates from the 1700s. |

|

Onkotogami |

御事紙

おんことがみ |

A packet of folded papers euphemistically referred to as 'paper(s) for the honorable act', while in fact they were the papers used by prostitutes to clean themselves after engaging in sex.

The image to the left is a detail from an erotic print by Kunisada. Holding the onkotogami in the mouth, by the teeth, was considered an erotic imagery clear to any worldly Japanese at that time. This example comes from the Lyon Collection. |

|

Onmyōdō (also Ommyōdō) |

陰陽道 おんみょうどう |

Literally 'The Way of Yin and Yang'. Also known as On'yōdō. "...originally [it] referred to the world view and practices found in the... I Ching or Book of Changes..."

|

|

Onmyōji |

陰陽師 おんみょうじ |

A diviner, sorcerer, exorcist or medium who uses their knowledge of yin and yang as a source of their powers. |

|

Onna budō |

女武道

おんなぶどう |

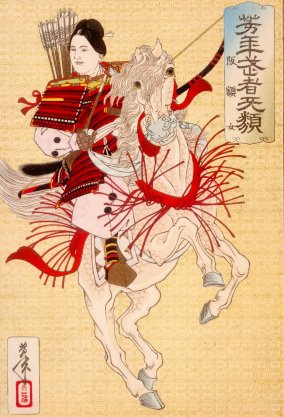

A female warrior.

The image to the left is from a print by Yoshitoshi of Hangaku Gozen (板額御前). |

|

Onnadate |

女伊達 おんなだて |

"...a female champion of the oppressed..." Her male counterpart is the otokodate. (See that entry below.) |

|

Onnagata (or oyama) |

女形

おんながた

|

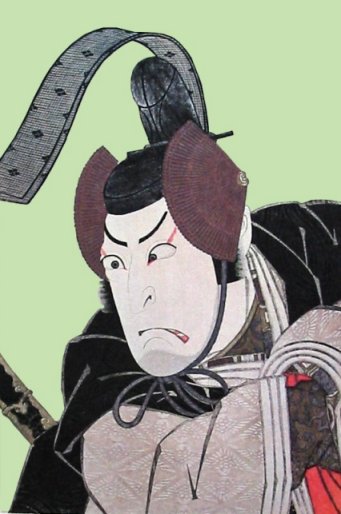

A male actor performing in a female role in the kabuki theater. There is a long tradition of male only theater. In Shakespeare's day this was true. However, in Japan kabuki was first performed by women - that is until they were outlawed. Then young boys played many of the female roles until, of course, they were outlawed too. There was nothing left to do for the theater than to adapt and to draw on the talents of its remaining all male casts. Many of these men who were definitely heterosexual at home became the paragons of femininity and were often the trend setters for real women who chose to emulate them.

Donald Shively in an essay noted that "The Edo onnagata, Segawa Kikunojō II [1741-73], had three homes, three mistresses, and supported fifty-three people." ("The Social Environment of Tokugawa Japan", in Japanese Aesthetics and Culture: A Reader, Nancy G. Hume, SUNY Press, 1995, 226.) I mention this because many people believe that onnagata were gay, but this was not necessarily so. Maybe some of them were and maybe some were bisexual, but like the rest of the male population some of them like just plain liked women - exclusively.

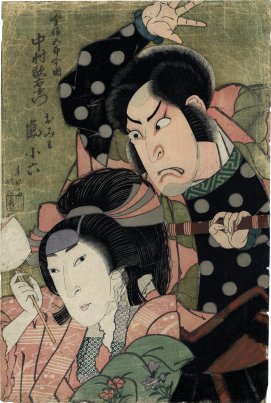

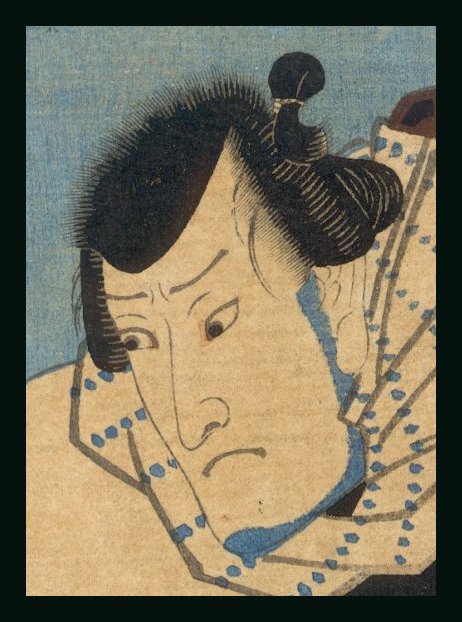

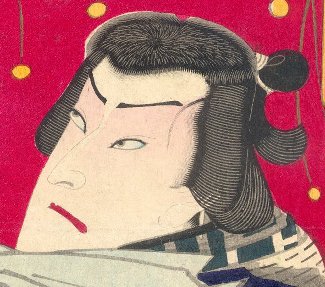

The image to the top left is a detail from the 20th century master Natori Shunsen (名取春仙) of Nakamura Tokizo as Yamauba Yaegiri from 1952. The one below that is by Toyokuni III from 1849-53.

One of the tell tale signs that you are looking at an onnagata print is the cloth which covers a part of the forehead. (See our entry for murasaki bōshi.) However, this is not always true and can be a tricky matter when one is trying to identify the subject matter. The bottom example to the left is just such a case. Although it is clearly identified and known to be an onnagata there is no murasaki bōshi. That example is also by Toyokuni III from 1860. 1, 2

The kanji for onnagata, 女形, can also be read as oyama and these terms seem to be interchangeable with each other.

|

|

Onoe Kikugorō III |

尾上菊五郎

おのえ.きくごろう |

Kabuki actor (1808-60). He held this name Kikugorō III in 1815.

|

|

|

四代目尾上菊五郎

|

Kabuki actor (1808-60). He held this name from 9/1855 until 6/1860. "Kikugorō devoted himself exclusively to female roles (onnagata). In the 1850s he was the most popular performer of middle-aged female roles." Quote from a footnote in Andon 96, May 2014, p. 63.

The image to the left is a shini-e or memorial print from 1860. It is from the collection of the Tokyo Metropolitan Library. |

|

Onoe Kikugorō V |

尾上菊五郎

おのえ.きくごろう |

Kabuki actor (1844-1903). |

|

Onryō |

怨霊

おんりょう |

Onryō "...were the individual spirits of those who died in unnatural or untimely circumstances and thus roamed this world creating havoc until placated (either by taking revenge on the wrongdoer or by acts of pacification by the living, e.g. exocism, recitation of Buddhist scriptures and of the name of the Buddha Amida... [whereas] goryō were the functional spirits of those who died of political intrigue and were believed to have transformed into epidemic or disaster-causing spirits." (See our entry on goryō on our Ges thru Hic page.)

The image of Oiwa to left is from an exhibition in 2018 at the musée du quai Branly - Jacques Chirac.

|

|

Oranda-tsūji |

阿蘭陀通事 おらんだ.つうじ |

"...the bi-annual visits of the Dutch traders were an important chance for the shogun and Japanese scholars to gain access to information on world affairs and new developments. According to Stanlaw (2004 : 47), the linguistic aspects of these encounters were managed by the so-called oranda-tsuuji (Dutch interpreters), who also served as customs officials. Dutch was the only Western language that was allowed to be studied during the sakoku and the oranda-tsuuji were the only ones who were given this privilege. These scholars also observed the Dutch doctors and occasionally conversed with them to gain insight on Western medicine. This unofficial interest became the foundation of ran-gaku (Dutch Studies), the study of Western science and medicine during the isolation. This field was expanded when shogun Tokugawa Yoshimune lifted some of the bans established by his predecessor and allowed the importing of books containing secular knowledge, thus enabling the oranda-tsuuji to expand their knowledge of the Dutch language together with other topics, resulting in the first Dutch-Japanese dictionary in 1796." English in Japanese Language and Culture: A Socio-Historical Analysis by Kai Hilpisch, p. 8.

Haruma wage (波留麻和解) was the name of the first Dutch-Japanese dictionary. |

|

Orchid (Ran) |

蘭

らん

|

One of the "Four Gentlemen" or Shikunshi which are flowers which mirror positive human traits. The other three are plum, bamboo and chrysanthemum. Borrowed from the Chinese and linked to confucian concepts.

"One of the 'four princes' of Chinese painting, the orchid nonetheless failed to attain even middle-class status in Japanese heraldry, and was one of the more neglected design motifs. No family appears to have used it as a crest."

Quote from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, published by Weatherhill, 1991 edition, p. 66.

The quote seen above is rather odd because there are at least ten different designs for crests or mon using an orchid pattern which I am aware of. If families didn't use them then who did? Businesses? And why? 1 |

|

Orihon |

折本

おりほん |

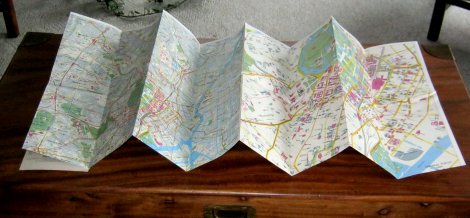

"The development of alternatives to the roll in China is difficult to date, but it appears that at some time during the Tang period long rolls consisting of sheets of paper pasted together began to be folded alternately one way and the other to produce an effect like a concertina. It has been supposed that this form was suggested by the palm-leaf books which transmitted Buddhist texts from India to China. However that may be, it is in any case a fact that the concertina form was primarily used in China, and subsequently in Japan, for Buddhist texts. Books of this format are called orihon 折本 in Japan, and the format survived until the nineteenth century and beyond for printed Buddhist sūtras and occasionally for other books, such as reference lists, calendars, and folding maps." Quoted from: The Book in Japan: A Cultural HIstory from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth Century by Peter Kornicki, p. 43. |

|

Ōsaka (as regards their prints vs. those of Edo) |

大阪 おおさか |

City second only to Edo in the production of Ukiyo prints. |

|

"The Ōsaka printers used a wider range of colours than those from Edo. Their number of basic pigments was greater, while also more mixtures were made, mixtures of the basic pigments with each other, and with black and white. In two or three black pigments, often applied with refinement and highly determining the atmosphere of a print."

Quote from: Ōsaka Kagami, by Jan van Doesburg, published by Huys den Esch, 1985, p. 6.

"Despite the considerable contact with developments in Edo, since both actors and artists traveled freely between these centers, the prints produced in Osaka have an individual character which usually renders them unmistakable."

Osaka "...prints date almost exclusively from the first half of the nineteenth [century]. Typically they are finely engraved and printed, with pure, opaque pigments on high-quality paper. Editions were small and often for private rather than public circulation and many of the artists were either amateurs or, at most, part-time designers. Certainly by contrast with the professional artists of Edo there were few Osaka artist with any considerable output..."

Quote from: The Art of Japanese Prints, by Richard Illing, published by Gallery Books, 1983, p. 145.

"The enthusiasm with which the great Japanese printmakers of Edo were suddenly discovered in Europe during the third quarter of the nineteenth century did not extend to their contemporaries in Osaka. In some ways this is strange..."

"As the stature of the Edo masters came to be recognized in the West, the Osaka school continued to attract little attention; instead, its flamboyance was dismissed with notable condescension." Only the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston purchased numerous Osaka prints.

Source and quotes from: The Theatrical World of Osaka Prints, foreword quotes by Evan H. Turner, Director, authors Roger Keyes and Keiko Mizushima, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1973, p. 9.

According to Keyes and Mizushima there are three reasons for the neglect of Ōsaka prints vis-à-vis those from Edo. The first is historical: The great center of production was Edo even when the output and innovations had been greatly influenced by styles already fully developed by artists from the Kyōto-Ōsaka region.

"The second unfortunate consequence of the notion that Japanese prints are an Edo art form has been the neglect of other schools.... The only regional prints to seriously rival those of Edo on their own ground of quality in design, engraving, and printing, were those produced in Osaka. But in a century of the study and collecting of Japanese prints, those of the Osaka school have been virtually ignored." Since they were neglected for so long they weren't available to students and collectors for study.

The third reason for the neglect of Osaka prints was due to the fact that they almost exclusively limited their subject matter to kabuki while Edo artists gave us warriors, ghosts, landscapes, beauties, parodies, erotica, etc.

Ibid, quotes by Keyes, pp. 15-17. |

||

|

|

||

|

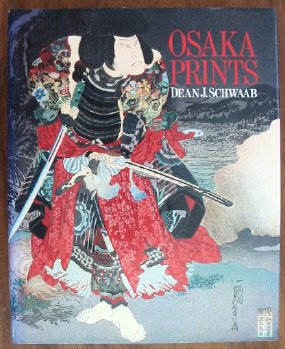

Osaka Prints |

|

A good source book by Dean J. Schwaab published by Rizzoli in 1989. Lots of excellent information and color plates and a good source of material for students of this area of Japanese woodblock prints. 1 |

|

Oshidori |

鴛鴦

おしどり |

Mandarin duck(s): Aix galericulata

For more thoughts and images dealing with oshidori please go to our new blog at |

|

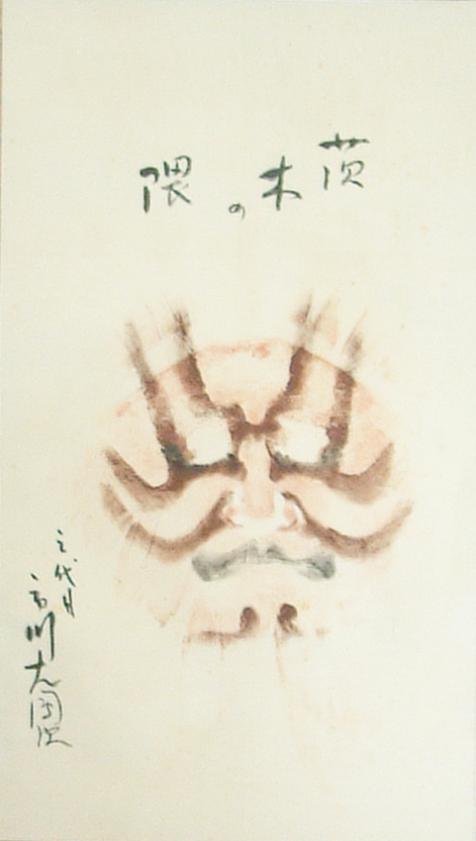

Oshiguma |

押隈 or 押し隈

おしぐま |

"The curtain closes to shouts and applause, and the assistants hurry to remove the actor's heavy costume and wig. The actor then hurries to his dressing room where he takes an oblong towel of silk, closes his eyes, and with great care presses the material first to his forehead. Then, working his way slowly down his face, he presses it around his eyes, under his nose, round to his ears, and beneath his chin. The material covers his face like a shroud. As the streaks of makeup begin to show through the perspiration-dampened cloth, an assistant presses the actor's fingers to the parts he has missed or that do not show up clearly. Then he peels off the silk to reveal the oshiguma, a perfect mirror-image of the actor's face in that particular role on that particular day. This procedure is likely to be repeated every day of the month-long run, and when the pressings are completely dry, the actor signs, dates, and stamps them with his personal seal. Oshiguma are highly valued mementos of the actor's performance and may be given away to the fans or occasionally sold for a charitable cause. ¶ Despite the great age of kumadori makeup style, the practice of taking an oshiguma appears to be a comparatively recent phenomenon, initiated by Ichikawa Danjuro IX (1838-) in the Meiji era. He is said to have hit upon the idea while pressing a cloth to his face to remove the makeup for the main role of Shibaraku. Advances in the quality of the actual makeup, which enabled it to stick and remain on the cloth, may have also contributed to the discovery. In any case the practice soon became common among the stars." Quoted from: Kabuki: A Pocket Guide by Ronald Cavaye, pp. 86-87.

The image to the left is an oshiguma of Ichikawa Sadanji III from the collection of the Mead Art Museum at Amherst. |

|

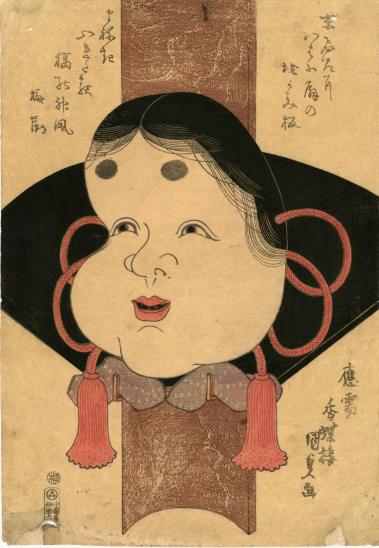

Otafuku |

お多福 おたふく |

"Otafuku is considered to be a reincarnation of the Shinto deity Uzume Mikoto, who helped to lure the sun goddess, Amaterasu, out of a cave during a dramatic eclipse sequence, as revealed in the Nihongi. In Tokyo, people carried pictures of Otafuku around on bamboo rakes during the festival of Tori no Machi at the three shrines called O Tori Jinja during the days of the Cock in the eleventh month. During the festival, people bought ornamental rakes and used Shinto symbols to attract good luck for the coming year. On these days the back gate of the Yoshiwara pleasure district would be thrown open." Quoted from: The Sound of One Hand: Paintings and Calligraphy by Zen Master Hakuin, fn. 59, p. 266.

"Oto, or Otafuku, is a

modification of Okame [the figure who lured Amaterasu out of the cave]... A

character found in Kyōgen after the fifteenth century. Otafuku is a term,

with a vulgar connotation, usually applied jokingly to 'big' women. Kyōgen

masks tend to emphasize one particular aspect of facial characteristics, and

in this case the exaggeration of the cheeks and mouth results in a grotesque

parody of female beauty."

Both examples shown above and to the left - a detail - come from the Lyon Collection. Click on them to go to the specific pages devoted to these prints. |

|

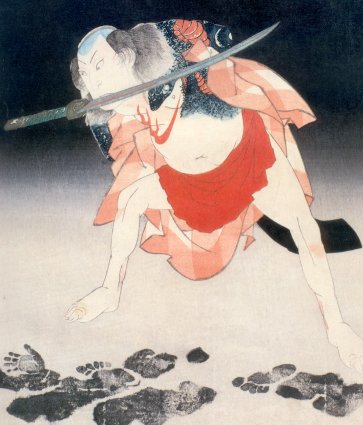

Otokodate |

男伊達

おとこだて |

A chivalrous commoner. Said to be a protector of the little man against abuses by samurai thugs and others abusing their authority. Although they were viewed somewhat the way we view Robin Hood that was probably a more romanticized than real interpretation. There were numerous such figures in late 18th and 19th century kabuki plays and ukiyo prints.

In time whole gangs of otokodate came together and may have preyed on the innocent themselves. In fact, some view them as the predecessors to today's yakuza.

The detail to the left is an image of Danshichi Kurobei by Hokuei. Kurobei is only one of many otokodate featured in kabuki and in serialized printed books. After getting out of jail for killing the retainer to an evil samurai he is often portrayed either slaying his wicked father-in-law, covered in blood or washing the blood of from his extremely messy deed. |

|

Since otokodate were not allowed to carry samurai swords they armed themselves with anything at hand which could be used as a weapon: iron staffs or even heavy iron fans called tessen (鉄扇 or てっせん). "Their fans were so deadly that even they were afterwards proscribed. By then the smoking of tobacco had become habitual, and the otokodate smoked out of hardly less lethal, foot-long metal-pipes." Quoted from: U. A. Casal in his "Lore of the Japanese Fan", Monumenta Nipponica, vol. 16, no. 1/2, 1960, p. 82

Sooooo... You must be asking yourself "Then why is Danshichi Kurobei holding a sword in his mouth in the image shown above?" Well, all I can say is 1) it must either be poetic license or 2) or he must have gotten ahold of a sword in the process of killing his wicked father-in-law or 3)... And you can fill in other possibilities here. |

||

|

|

||

|

Ōtorige |

大鳥毛

おおとりげ |

A feathered banner. All we could find was the name and the physical description of this item. It appeared in a footnote by Gerstle in a book on Chikamatsu. However, since we want to know the names of everything we see in Japanese prints we felt this was worth adding to the list. Maybe someone more versed can fill in more details later.

To the left is a detail from a Hiroshige print of a daimyo's procession in Edo at the Nihonbashi Bridge. It shows two types of ōtorige. |

|

Perkin, William |

|

Scientist 1838-1907. First creator of a synthetic aniline dye in 1856. |

|

Plum (Ume) |

梅

うめ |

One of the "Four Gentlemen" or Shikunshi which are flowers which mirror positive human traits. The other three are orchid, bamboo and chrysanthemum. Borrowed from the Chinese and linked to Confucian concepts. 1 |

|

Po Chü-i (or Haku Kyoi) |

白居易 (in Chinese)

はくきょい (in Japanese)

|

An important Chinese poet (772-846) who strongly influenced Japanese intellectuals and literary figures. As you will see from the entry below Po's works showed up in both visual and written from the as early as the turn of the 11th century to well into the 19th.

"...Po Chü-i became the favorite poet of the Heian times - some say because his poetry was reputed to be easy. He was the Chinese poet to whom allusions and from whom recollections, were most frequent in Heian Japan. His verses were offended used for kudai waka [Japanese poems based on Chinese texts], and he epitomized Chinese poetry. So far was that the case that a nō [play], Hakku Rakuten, depicted the divinity of Sumiyoshi who represented Japan and its poetry, driving away an invasion by the Chinese poet and his nation's prestigious poetry." ¶ Murasaki Shikibu, the author of the Tale of Genji makes and early reference to the poem "A Song of Unending Sorrow" by Po Chü-i. [In Chinese it is Chang-hen-ge (長恨歌): In Japanese it is the Chōgonka (ちょうごんか). See our entrries on nashi and Yang Gui-fei for more information.]

Source and quote: The Princeton Companion to Classical Japanese Literature, by Earl Miner , Hiroko Odagiri and Robert E. Morrell, 1988, p. 160.

In Japan he is known as Haku Kyoi (白居易) or Haku Rakuten or (白居天).

Alternate readings of his name in English are Bai Juyi and Bo Ju-yi.

The images to the left and above are details from a print by Hokusai. |

|

"The T'ang, everyone with an interest in Chinese literature agrees, was the great age of Chinese poetry, in the classical language. Three of its poets [Tu Fu, Li Po and Po Chü-i], because of their vast scope and creativity, loom particularly large... what is Po Chü-i most famous for? Simplicityof language, for one thing, especially in comparison with the others in the triad. For the large number of his works that have been preserved - far more than any of his contemporaries. And for an abiding desire to portray himself, whatever he may have been in real life, as a connoisseur of everyday delights, a man confronting the world, particularly in the years of old age, with an air of humor and philosophical acceptance." ¶ In his youth "...he embraced the Confucian ideal of poetry as a vehicle for exposing and righting the ills of time, he wrote caustic poems of social and political satire. Also a product of youth is the famous narrative poem 'Song of Everlasting Regret' richly romantic in tone, which tells of the tragic love between Emperor Hsüan-tsung and the beautiful Yang Kuei-fei... There are poems on religious themes reflecting his early interest in Buddhism and Taoism and his increasing devotion to Buddhist study and practice in later years. And then there are poems of intense sadness, occasioned by partings or deaths, in some cases the deaths of his own children, or by moods of deep depression, though he felt that by indulging in such outpourings of emotions he was in a sense betraying the Buddhist ideal of calm and detachment that was his professed goal. ¶ In the end, however, it is the simple, low-keyed works depicting his daily moods and activities, often almost prosy in expression, for which he is best remembered. These are the poems that exercised the greatest influence on the poets of succeeding centuries..." (Quoted from: Po Chü-i: Selected Poems, by Chu-I Pai, Juyi Bai and Burton Watson, Columbia University Press, 2000, pp. ix-x) |

||

|

|

||

|

Port Arthur |

旅順 りょじゅん |

Scene of a Japanese victory over the Russian in 1905. 1

Below is a Japanese lithograph of the destruction of the Russian Fleet at Port Arthur. We found this at commons.wikimedia. Text about the battle will follow eventually.

|

| Prussian blue |

プロシヤ青 |

A strong inorganic pigment imported into Japan beginning in the 1820s. 1 |

|

Publisher |

版元 はんもと |

|

|

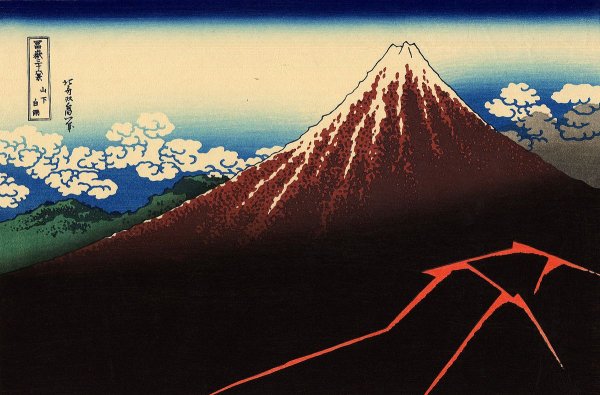

Rai |

雷

らい |

Lightning, thunder or thunderbolt - There is a story that as Hokusai was walking along one day there was a lightning strike very close nearby. After that he called himself Raishin (雷震) or Raitō (雷斗). Of course, this story sounds credible because Hokusai changed his name more than almost any other known artist.

Above is a modern copy of one of Hokusai's most famous images - with lightning prominently represented in the lower right. The photo of the lightning strike to the left has been cropped from the original which was taken by John Fowler and posted at Flickr. |

|

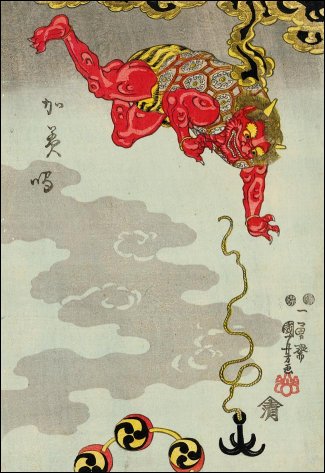

Raijin |

雷神

らいじん |

The god of thunder and lightning: Merrily Baird notes that "Japanese art depicts Raijin, who is also known as Raiden and Kaminari-Sama, in demonic form.... [W]hen he is without his thunderbolts, his primary attribute is a barrel drum or circlet of barrel drums decorated with the three-comma (mitsu tomoe) motif." (Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design p. 40)

"The rolling thunder is made by Kaminari-san [かみなりさん] or Raijin. He lives up on the summer clouds, and is always naked, wearing only a loincloth made of tiger skin. He has horns on his head and tusks in his wide mouth. On his back, he carries about a dozen round, flat drums, arranged in a circle, and holds drumsticks in his hands. When he beats his drums, the thunder rolls through the sky and puts fear into the people on earth. ¶ He comes down to this earth whenever he wishes to eat o-heso [お臍] or human navels. He is very fond of them, and this fondness causes him to fall from the sky. Whenever children run around naked in summer, mothers say, 'Put on your clothes or Kaminari-san will come and take your o-heso. Then little boys will hurry to cover themselves up. Many old people still put their hands on their stomachs whenever they hear the distant rolling of thunder." (Quoted from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, The Japan Times, Ltd., 1985, p. 345) |

|

The images shown above are from a print by Kuniyoshi from the early 1850s. Although I can't be sure it seems to represent an actor in a theatrical performance playing the role of the thunder god. These are shown courtesy of my great friend M. Thanks M! |

||

|

|

||

|

Rain & Snow: The Umbrella in Japanese Art |

|

An excellent catalogue by Julia Meech of a show held at the Japan Society in New York in 1993. It includes a description of the techniques of production and a history plus annotated entries on everything from Kuniyoshi to Christo. |

|

Rakkan |

羅漢 らかん |

Buddhist 'saints': In China they were referred to as lohans wile in India they were called arhats. It is also called arakkan (阿羅漢) in Japanese. |

|

Raku |

楽

らく |

"...under the guidance of Sen no Rikyū (1522-91), tea-master to the military lords Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a tile-maker called Chōjirō (1516-89) began to create a new kind of low-fired, hand-modelled tea utensil specifically for the tea ceremony. Chōjirō's successors took the name Raku 楽 (one of the characters of Hideyoshi's Jūraku Palace, where Chōjirō worked), and became official suppliers of tea wares used by the tea schools in Kyoto. Being simple and unstandardized in technique, and requiring only a small, unsophisticated kiln, Raku ware was ideally suited for oniwa-yaki [small garden-firing kilns]. Thus many private Raku kilns were set up at private homes or near the precincts of temples." Quoted from: Master Potter of Meiji Japan: Makuzu Kōzan (1842-1916) and His Workshop by Moyra Claire Pollard, Oxford University Press, 2002, p. 9.

To the left is a 19th century Raku-style tea bowl in the Freer/Sackler Galleries. It was posted at Wikimedia.commons by Gryffindor. |

| Ranpeki |

蘭癖 らんぺき |

"Dutch mania": A passion for

all things Dutch or Western in Japan during the reign of Tokugawa Yoshimune

in the 18th century. In 1858 Hotta Masayoshi, the feudal lord of Sakura, "Believing it impossible to keep the country closed, in 1858 he negotiated a commercial treaty with the American consul, Townsend Harris, provoking a crisis for which he was eventually put under house arrest. Hotta also devoted his energies to reforming his own domain, to which he brought scholars of both Eastern and Western learning. The famouse Confucian scholar Yasui Sokken taught at the domain school, and Satō Taizen, a well-known scholar of Rangaku (Dutch studies, or more generally, Western learning), started his school, Wada Juku, in Sakura and later, at the invitation of Hotta, established Japan's first private hospital, Jutendō, where he practiced surgery. Hotta's encouragement of Western studies earned him the nickname Rampeki (Dutch maniac)." Quoted from: Tsuda Umeko and Women's Education in Japan by Barbara Rose, p. 14. |

|

Rangaku |

蘭学 らんがく |

Originally it was Japanese studies of Holland, but in time came to mean the studies of all Western knowledge. "Around 1740 interest in European medical science was promoted by the Shogun, who ordered his librarian and his physician to learn Dutch. He also permitted the Japanese interpreters, who always accompanied the Dutch, to possess and read Dutch hooks, up till then forbidden goods to all Japanese. This more liberal climate seems to have encouraged Japanese physicians of the 'Dutch school' to start translating Dutch textbooks on medicine, of which the first one was printed in 1774. These physicians formed the nucleus of the so-called Rangaku-sha [蘭学者], or 'Hollandologists', who gave the study of Dutch - or rather European - medicine in Japan a new impulse. Many translations of medical texts followed." Quoted from: Warm Climates And Western Medicine: The Emergence Of Tropical Medicine, 1500-1900 by David Arnold, p. 44. |

|

In 1720 the 8th shogun Yoshimune (r. 1716-45) allowed the importation of Dutch books. "In addition to Dutch medical knowledge, to supplement the work of his doctors trained in Chinese medicine, Yoshimune was motivated by an interest in Dutch mathematics for its applications in astronomy and the related work of producing accurate calendars. He commissioned scholars to study the Dutch language, to collect Dutch books, and to develop the expertise to translate them, thereby sanctioning a nucleus of scholarly activity in his capital, Edo (now Tokyo); by the end of the eighteenth century, this set of studies became known as 'Dutch learning.' Apart from mathematics, astronomy, and medicine, Japanese students of Dutch learning pursued knowledge of world geography, natural history, perspective painting, and other related crafts and branches of learning. Although Dutch learning in the eighteenth century was markedly amateur, it became increasingly professional in the nineteenth century with the establishment of an official Translation Bureau in 1811 under the auspices of the shogunate's Observatory. During the first half of the nineteenth century, as American, British, and Russian ships encroached into Japanese waters, the shogunate added military science, gunnery, and ordnance to the content of Dutch learning."

"Japanese doctors, for example, would visit Dutch settlements in the guise of servants in order to find out about Western medicine." Quote from: Chinese Medicine by Paul Unschuld, p. 97.

"Japanese doctors... began to study European medicine, especially surgery, not only because it became fashionable, therefore profitable, but also because it produced more convincing results than Chinese methods in which they had been trained. Astronomy came into favour for its relevance to calendars, though the first clear illustrations of heliocentric theory came in fact from an artist, Shiba Kōkan. Much of what was done was in the 'amateur' tradition cherished by Chinese literati. Inō Tadataka (Chūkei), who was by trade a sake-brewer, turned in later life to the study of surveying. Using western instruments, he prepared a remarkably accurate map of the whole of Japan in the first few years of the nineteenth century. Other aspiring scientists, taking advantage of the visits made to Edo by the Dutch factors from Nagasaki, bombarded them with requests for clocks, telescopes, barometers, even Leiden jars. Colour prints of Dutch life at Deshima found a ready sale." Quoted from: The Japanese Experience: A Short History of Japan by W. G. Beasley, p. 203.

"In particular, reference should be made to the role of Osaka, the bustling commercial centre of Tokugawa Japan. The special character of Osaka Rangaku was that its emergence paralleled the growth of a bourgeois chonin life-style in Osaka and had an intimate relationship with the new forms of popular culture flourishing in that fast-growing city. Interestingly, this was a different atmosphere from the one in Edo which had seemingly been conducive to advances in medicine. Osaka, however, seemed to engender a rather strong sort of fascination with things Dutch, leading from the kind of basic concern with mathematics one might expect in a commercial environment to a serious study of Western astronomy and physics. Naturally, some of this kind of interest was little more than faddishness, characterized by the Japanese in such derogatory terms as komoshumi (hobby red-hairs) and Ranpeki (Dutch habits). However, in a more serious vein, the popular culture of Osaka seems to have given rise to the sort of practical rationalism which provided a basis for the investigation of Western science." Quoted from: Japan and the Dutch, 1600-1853 by Grant Kohn Goodman, p. 117.