|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY Ro thru Seigle |

|

|

The molecular model on Lonsdaleite is being used as a marker for new additions from January 1 to May 31, 2021. The piece of sulphur posted at Wikimedia by Rob Lavinsky was used from June 1 thru December 31, 2020.

The detail from the diadem of

the Empress Eugénie |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Rokudō, Rokudō no suji, Rokuro-kubi, Rokushaku, Rokushaku-kyūmai, Rōnin, Teddy Roosevelt, Rosoku-tate, Russo-Japanese War, Ryōgoku Bridge, Ryūgū, Ryū no tamago, Sagi, Sagi musume, Saigō Takamori, Saikaku, Sai no kawara, Sajiki, Sajiki, Sakaki, Sakoku, Sakura, Samegawa, Samurai,

Sanbasō, Sanko, Sanmaitsuzuki, Santō Kyōden,

Sanzu no

kawa, Saru,

Sasarindō, Sashimono, Sawamura Gennosuke II,

Sawamura Sōjūrō V, Sawamura Tanosuke II, Sayagata, Dean J. Schwaab, Sedai, Segawa Kikunojō V, Seigaiha and Cecilia Segawa Seigle

六道, 六道の辻, 轆轤首, 六尺, 六尺救米, 浪人, 蝋燭立て, 日露戦争, 両国橋, 竜宮, 鷺娘, 西郷高盛, 犀角, 桟敷, 歳時記, 犀角,賽河原, 榊, 鎖国, 桜, 鮫皮, 侍, 三番叟, 実盛物語, 算木, 珊瑚, 三鈷杵, 三枚続,

山東京伝, 三途の川, 猿,

笹, 笹紅, 笹竜胆, 指物, 沢村源之助, 沢村宗十郎, 澤村田之助, 紗綾形, 歳時記, 世代, 瀬川菊之丞 and 青海波 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Rokudō |

六道 ろくどう |

In Buddhism the Six Realms (or Paths) of Existence: "Discussions of the Six Paths, or circumstances into which a being may be born, usually treat them in ascending order of desirability: hell, the world of hungry spirits, the world of animals, the world of eternal armed conflict, the world of men, and heaven." (Quoted from: The Tale of Heike by Helen Craig McCullough, p. 469. |

|

"Karma determines 'the direction of travel, the rate of travel, and the specifics of one's next birth' across the cosmology of six paths. Insofar as one's karma is always in the process of becoming, one is always on the way to being reborn in another existence, another being. In ascending order, the six paths are: sufferers in hell (jigoku), hungry ghosts (gaki), animals (chikushō), warriors (shura), human being (ningen), and heavenly beings (tenjō)." (Quoted from: Theatricalities of Power: The Cultural Politics of Noh by Steven Brown, p. 51)

Plutschow cites the work of Tsukudo Reikan (筑土鈴寛: 1901-1947) who posited that tales like the that of the Heike and which were originally chanted were meant as prayers for the souls of those who were lost in the struggle. Plutshcow notes specifically as one example the drowning of the child emperor Antoku (安徳天皇). "He calls the Tales a monogatari literature to pray for victims' karma and claims them to be a 'Rokudō rinkai monogatari', or a tale about reincarnation into the Six Paths. Rokudō is a scheme of reincarnations according to karmic reward or punishment for anterior acts, which would push a person either up or down the Six Paths: Gods, Humans, Warriors, Animals, Hungry Ghosts and Sufferers in Hell. In one of the Tales' ending chapters entitled 'The Six Paths,' the events are explained by the Buddhist notion that all is subject to change, even life and its ages of glory and passion. Life is seen as a passage through Six Paths and thus the drowning of the child-Emperor Antoku is seen as a fall from what appears to be a substage of heaven into hell. Such fallen people as the Heike and the child-Emperor become then the Tales' evil spirits which must be dealt with by constant prayer. To appease these spirits was the sacred duty of the living." (Quoted from: Chaos and Cosmos: Ritual in Early and Medieval Japanese Literature by Herbert E. Plutschow, p. 224)

As you know Buddhism came to Japan via China which got it from India. "The transmission of Buddhism to China at the beginning of the common era introduced the principles of karma and rebirth, the heart of the Buddhist afterlife. Although the six paths of rebirth was a new concept to the Chinese, the realm of hungry ghosts immediately struck a resonating chord because of its similarities to traditional ideas of the dead as wandering, disembodied spirits; similarly the bureaucratic metaphor was transposed onto Buddhist retributive hells." (Quote from: The Making of a Savior Bodhisattva: Dizang in Medieval China by Zhiru, p. 199)

As for Japan - "The concept of the Six Paths entered Japan in the tenth century, and became influential in art and culture from the eleventh century onwards. Both as an intellectual doctrine and in religious practice it is closely related to the worship of Amida: the six forms of Kannon, his chief lieutenant and the most compassionate of all bodhisattvas, operate on his behalf in each of the six paths of existence to rescue sentient beings from the chains of causation." (Quoted from: Religion in Japan: Arrows to Heaven and Earth from an article by David Waterhouse, p. 18)

Our great contributor Eikei (英渓) points out that the information quoted above is based on a different interpretation of the purpose of the Six Paths. There are others. For example: "The six paths were a recurring theme in medieval Japanese literature, and remain more less familiar to people today, although other concepts of the afterlife are equally or more compelling. The Pure Land, for example, does not figure in the traditional Buddhist cosmology of six paths. Nor does the generic East Asian (originally Chinese) understanding of ancestral spirits sit very well with orthodox Buddhist cosmology as it was formulated in India. The ancestral spirits, as most Japanese today conceive of them, retain basically the same identities as when they were alive. As spirits, they can come and go, but they are often understood to occupy the mortuary tablets (ihai) enshrined in a family's household buddha altar (butsudan)." (Quoted from: Living Buddhist Statues in Early Medieval and Modern Japan by Sarah J. Horton, p. 115)

On the other hand William LaFleur in his Karma of Words: Buddhism and the Literary Arts in Mediaeval Japan states on page 27: "The basic portrait of the universe in terms of a taxonomy called the rokudō, or 'six courses,' was universally accepted by all the schools of Buddhism and included the belief that karmic reward or retribution for anterior acts pushed every kind of being up and down the ladder of the universe." The Chinese term for rokudō is liu-tao. 道 is the Tao of Taoism or the Way. ¶ The rokudō is mentioned in a quite a few Buddhist texts included the Lotus Sūtras of the Hokke-kyō.

Some have argued that the Japanese Buddhist concepts of heaven and hell were not as compartmentalized as the rokudō would indicate. "...instead of seeing the six realms as a primarily vertical structure of highly compartmentalized cosmic realms, Japanese assimilated the rokudō schema into the old horizontal cosmologies of yomi no kuni, 'the land of gloom,' and tokoyo no kuni, 'the land over there.' " (Source and quote from: Japanese Civilization: A Comparative View by S. N. Eisenstadt, p. 236)

Lafcadio Hearn noted that there is a Japanese Buddhist saying: "The six roads are right before your eyes." (Quoted from: In Ghostly Japan, p. 188) |

||

|

|

||

|

Rokudō no suji |

六道の辻 ろくどうのつじ |

Crossroads of the Six Realms - the place in this world that lies directly above the palace of Emma, the overlord of hell. |

|

Rokuro-kubi |

轆轤首

ろくろくび |

By using Yokai Attack: The Japanese Monster Survival Guide by Matthew Alt and Hiroko Yoda I discovered more about rokuro-kubi than I had found anywhere else in English. (pp. 134-7) There are two kinds: The first with a long extendable neck - often with purplish striations - which remains connected to the body and the second which is almost exactly the same but detaches itself from the body and roams about in search of sustenance. The rokuro-kubi is almost always seen in the form or an attractive well-dressed female. In fact, sometimes these yokai don't even know that they aren't human. It is only at night after they fall asleep that the transformation take place. Other than that they can lead rather ordinary lives, even getting married. Remember they tend to be rather fetching - at least most of the time. ¶ They feed on worms, grubs, other insects, lamp oil and human essence - mainly male. That could be one explanation for some men waking up tired and feeling drained. The ones that detach and fly about through the night often fly in packs. ¶ Alt and Yoda recommend that men avoid women who wear scarves and won't show their necks. They also note that while rokuro-kubi attacks may be somewhat debilitating they are seldom fatal.

One more interesting point about this creature: The first two kanji characters, 轆轤, can be translated as 'potter's wheel'. Think about it. When a ceramicist throws a pot it often shows striations which could easily be compared to the discolored lines found on the neck of rokuro-kubi. The kanji for -kubi means neck.

See also our entry on mikoshi nyudō.

C. Pfoundes wrote in 1875 in Fu-so mimo bukuro: a Budget of Japanese Notes "Some women are liable, while sound asleep and dreaming, to have their head leave their body, still slumbering, and roam about, the head only attached to the body by an almost imperceptible film. It is dangerous to arouse them till the head returns to its original position. |

|

Rokushaku |

六尺 ろくしゃく |

Palanquin bearers. It literally means 'six feet'.

Rokushaku were also employed in funeral processions. "The funeral took place after the procession from the home to the temple or funeral hall (saijō 斎場). The departure of the coffin [出棺] generally started at 10 a.m., but often enough it was behind schedule. The coolies were divided into rokushaku 陸尺, who carried the palanquin and the coffin, and hirabito 平人, who carried the paper flowers (renge 蓮華),fresh flowers, and lanterns." Quoted from: 'Changes in Japanese Urban Funeral Customs during the Twentieth Century' by M urakami Kōkyō in the 'Japanese Journal of Religious Studies'.

A rokushaku is also the name of the traditional g-string worn by Japanese men because of the supposed 6' length of cloth - or some such measurement.. |

|

Rokushaku-kyūmai |

六尺救米 ろくしゃく.きゅうまい |

A "tax used in paying the stipends of palanquin bearers; - rokushaku is said to be a corruption of ryokusha 力者, 'a strong person' who worked as a bearer of palanquins; it may also refer to a bar 6 shaku in length used for carrying palanquins." Quoted from: A Topical History of Japan, p. 82. |

|

Rōnin |

浪人

ろうにん |

A masterless samurai. Literally translated as 'floating men'. Originally this referred to peasants who left their land to work elsewhere where they continued to pay taxes. During periods of strife they hired out to fight for opposing armies. There was no intrinsic loyalty and they would frequently change sides.

During the Muromachi period (1333-1568) rōnin came to mean samurai who lost their overlords and hence their stipends. By the time of Hideyoshi the rising numbers of rōnin were seen as a rising threat to his regime. A few years later there may have been as many as 100,000 rōnin fighting on the side of Ieyasu with as many for his chief opponent. After Ieyasu's victory at Osaka there was no longer a need for services so these lordless samurai had to seek employment using some of the skill they had already developed - in the arts, as teachers, as instructors in martial arts, etc.

The most famous tale of masterless samurai were the result of criminal activity and confiscations. "...commonly known as the 47 Rōnin, who avenged the death of their lord in a dramatic vendetta in 1703 and were subsequently forced to commit suicide by the shogunate... Their selfless loyalty made them national heroes, and their story remains popular in the form of various dramas."

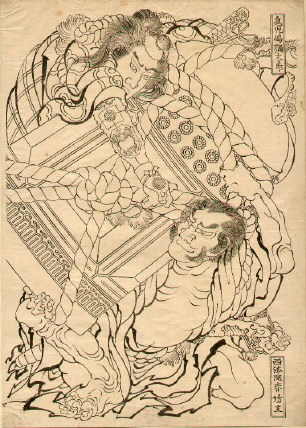

The image to the left is from a print by Kuniyoshi illustrating a scene from "Tale of the 47 Loyal Retainers" or Chūshingura mentioned above. The black and white patterning of their robes is specific group and their dramatization. (Source and quotes: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan entry by Charles Dunn, vol. 6, pp. 336-7) |

|

The first kanji character or rōnin is 浪 which means 'wave' as in ocean waves. The second character means 'men'. "Numbers of samurai, whose masters had been deprived of their positions or who had simply foresworn their allegiance to a lord, roamed the streets of Edo, creating social disorder. Known as ronin (wave men), they had no official income or right to fixed residence within the jokamachi. The life of the ronin was a mixed blessing, as they were accorded less respect than fully affiliated samurai in a country where identification was, and to some degree still is, consonant with respectability and recognition. The member of this dispossessed class eked out a living as best they could, hiring themselves as bodyguards to affluent merchants, or as instructors in military science: swordsmanship, equestrian skills, and archery. The more intellectually gifted became writers and calligraphy teachers, Confucian scholars or instructors in philosophy and Chinese literature. While employed they could live moderately well. Between posts they were reduced to sleeping in rudimentary shelters or beneath the eaves of temple roofs. While their existence may have been precarious, they enjoyed a degree of freedom almost unheard of in a city expressly conceived to inhibit personal choices and freedom of movement." (Quoted from: Tokyo: A Cultural History by Stephen Mansfield, p. 20) |

||

|

|

||

|

Roosevelt, Theodore |

|

President of the United States, winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1906 for negotiating the peace Between Japan and Russia. 1 |

|

During the conflict between Russia and Japan in 1904-5 both sides incurred terrible losses. But, Russia had definitely gotten the worst of it. They had lost on land and at sea. However, from a foreign perspective the cost to both sides was too great for the combatants to continue. Prior to Roosevelt's direct involvement there had been attempts at mediation. The Russians wanted to meet in one place, the Japanese in another. Finally the American President stepped in an suggested that both sides send emissaries to Washington, D.C. ¶ At the invitation of Roosevelt the representatives of the warring parties, Baron Kamura and Count Witte, met aboard the presidential yacht, the Mayflower anchored in Oyster Bay. ) On July 26 the New York Times said of this setting: "The Mayflower, which is one of the most luxuriously fitted vessels in the United States Navy, will furnish a suitable setting for the historic ceremony." ¶ Some authors claim that President surprised them when he suggested they all sit down together at lunch, breaking standard diplomatic protocol, but this may not be true because the N.Y. Times had already reported that the meal was already on the schedule. Whatever the circumstances this gathering may have helped break the ice and smooth the way somewhat for future negotiations. ¶ Since Washington could be insufferably warm in August, even on the water, the ambassadors were transported in separate vessels to the naval shipyard in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Like most such meetings things did not start off well. Japan wanted territorial gains including keeping Sakhalin Island which they had captured, special fishing rights, indemnity from the Russians for all of their wartime expenses, etc. Besides, the Japanese blamed the Russians for starting the war and thought that alone should make them pay for it. ¶ By August 29th the Japanese agreed to drop the indemnity in exchange for partitioning Sakhalin Island. No matter how it was worded that basically saved the day and the two parties came to an agreement. The treaty was signed on September 5. The next year President Roosevelt was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts.

"It was symbolic of the uncertain situation that the signing of the Portsmouth treaty should have been the occasion not for jubilation and thanksgiving but for mob attacks on police stations and official residences in Tokyo. The public, whose expectations had been raised by military successes and whose patriotic fervor had added fuel to insular arrogance, expressed their anger at what they viewed as meager fruits of victory. They thought they deserved more than was obtained at the peace conference and blamed this on the government and the United States who had mediated between the two combatants. It was as if domestic order was unraveling at the very moment when it should have been solidified." (Quoted from: The Emergence of Meiji Japan, edited by Marius B. Jansen, text by Akira Iriye, Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 324-5)

Americans were generally on the side of the Japanese in the war. The Kaiser had prodded his cousin, the Tsar, into starting the conflict, but when told of the naval victory of the Japanese at Tsushima congratulated the Japanese ambassador to Germany even comparing their accomplishment with that of the British over the French and Spanish at Trafalgar. (Source: Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852-1912, by Donald Keene, Columbia University Press, 2002, p. 617)

"Just before the peace treaty was signed, [Roosevelt] wrote the American minister in Peking, 'I was pro-Japanese before, but after my experience with the peace commissioners I am far stronger pro-Japanese than ever." (Ibid., p. 628) |

||

|

|

||

|

Rosoku-tate |

蝋燭立て

ろうそくたて |

A type of candle stand. We are not sure, but believe that this form of candle stand could only involve a single cup and spike.

Note: the photo to the left was posted at Flickr by yokokick. |

|

Russo-Japanese War |

日露戦争 にちろせんそう |

First great conflict with a Western power 1904-05. 1

I grew up shortly after the end of World War II. The conflict left a lot of bad feelings toward Japan so it is surprising to see how attitudes had changed so greatly since the turn of the 20th century. (See the comments made by Teddy Roosevelt in the section above.) ¶ The Americans and the British were definitely pro-Japanese at that time, especially vis a vis that of their rival, the Russians. In his "Letter from Japan" dated August 1, 1904 Lafcadio Hearn wrote: "This contest, between the mightiest of Western powers and a people that began to study Western science only within the recollection of many persons still in vigorous life, is, on one side at least, a struggle for national existence. It was inevitable, this struggle,—might perhaps have been delayed, but certainly not averted. Japan has boldly challenged an empire capable of threatening simultaneously the civilizations of the East and the West,—a mediæval power that, unless vigorously checked, seems destined to absorb Scandinavia and to dominate China. For all industrial civilization the contest is one of vast moment;—for Japan it is probably the supreme crisis in her national life." (Quoted from: The Writings of Lafcadio Hearn, edited by Elisabeth Bisland, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1922, p. 336. ) |

|

Ryōgoku Bridge |

両国橋

りょうごくばし |

"Located on the lower Sumida River between Nihonbashi and Honjo, Ryōgoku Bridge was the site of the most famous late-Tokugawa-period form of popular entertainment and entrepreneurship known as misemono (exhibitions, sideshows) ." (Quoted from: Civilization and Monsters: Spirits of Modernity in Meiji Japan by Gerald Figal, p. 21.) In fact, the author points out that the bridge had also become famous for its ghastly freaks and monsters. "A whale washed ashore and advertised as a monster sunfish, a hideous ugly 'demon girl,' a scale-covered reptile child, the fur-covered 'Bear Boy,' the hermaphroditic 'testicle girl,' giants, dwarfs, strong men (and women), the famous 'mist-descending-flower-blossoming man' who gulped air and expelled it in 'modulated flatulent arias,' and the teenager who could pop out his eyeballs and hang weights from his optic nerve, all attest to a libidinal economy in which a fascination with the strange and supernatural conditioned and sustained the production, consumption, and circulation of sundry monsters as commodities in 'the evening glow of Edo.' " (Ibid., p. 22)

The image to the left is from the series 100 Famous Views of Edo by Hiroshige. We found it at commons.wikimedia.

This was one of the major bridges in Edo and was constructed shortly after the major fire of 1657. "Officially known as Ohashi, the 'Great Bridge', it became known almost at once as Ryogokukbashi - the 'Two Provinces Bridge', as at that time the Sumidagawa was the boundary between Musashi province on the west and Shimosa on the east. The bridge became a center of amusements, the most lively in the capital. The numerous tea-houses and restaurants by the bridge were never quitet, ay or night. But things came to a fever pitch during the kawabiraki - the 'opening of the river', the main summertime festival connected with the Sumidagawa." Quoted from: Hiroshige: One Hundred Views of Edo by Mikhail Uspensky, p. 138. |

|

Ryūgū |

竜宮

りゅうぐう |

The underwater palace of the Dragon King - Carmen Blacker in her book The Catalpa Bow: A Study of Shamanistic Practices in Japan (p. 77) gives quite a vivid description of the palace: "The watery entrances, the lakes and pools, were believed to lead downwards to the world of Ryūgū. Plunge deeply enough into the pool and you would find yourself standing before the magical palace with its jade pillars, its walls of fish scales and carpets of sealskin."

An early name for Ryūgū was Tokoyo. Tokoyo is also the name of the Eternal Land as mentioned in the Nihongi. In Myth in History: Volume 2 of Mythological Essays by Peter Metevelis it says in footnote 11 on page 112: "[Ameterasu] first took up residence in her sanctuary [at Ise] after surfing ashore from the elesian land of Tokoyo across the sea (as did Toyo-tama Hime, the daughter of the sea god in the Ninigi cycle when she came ashore from the Dragon Palace)."

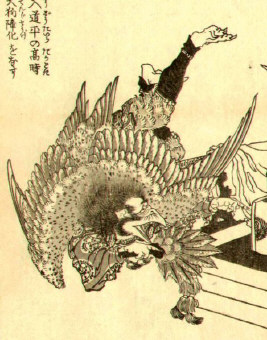

The image to the left is a Hokusai print of his version of Urashima Tarō visiting the underwater palace of the Dragon King. |

|

Metevelis also writes about the myth of a prince who looses a miraculous fishhook which he had exchanged with his brother. He looks for it in Ryūgū where he meets and marries the daughter of the Dragon King. She travels to the 'Middle Earth', our world, to give birth but abandons her husband and new born child because her husband observed the act of parturition. Her return to her father's palace closes off all future mortal travel there and therefore "...all hope of escaping mortality..." for the humans. "So now all fleshed souls are confined to Middle Earth, where death and metempsychosis are ordained." The prince had also received a gift of the tide-controlling jewel from his father-in-law. Whenever the prince brother might become belligerent toward him all he has to do is dip the jewel in the water and the tide will rise. Then when his brother has calmed down he dips it again and the tide ebbs. (Ibid., pp. 105-107)

In Buddhism as a Religion: Its Historical Development and Its Present Conditions by H. Hackmann from 1910 it says of one of the sūtras devoted to the life and teachings of Buddha that two of the sections are kept in the Dragon Palace for safekeeping. (p. 244) Hōnen Shōnin (法然上人: 1133-1212) wrote about the sūtras - both written and unwritten - covering the life of Buddha: "Among those already compiled, some are still hidden in the dragon palace and are not yet disseminated among humankind; others are still remaining in India and have not yet arrived in China." (Quoted from: Hōnen's Senchakushū : Passages on the Selection of the Nembutsu in the Original Vow, p. 130)

Carmen Blacker has written about a new sect called the Dragon Palace Family, Ryūgū Kazoku, which started at 11:30 A.M. on October 7, 1973 when a woman named Fujita Himiko has a vision. "She was standing outside a large cave near Kumamoto, Kyushu, in company with a woman ascetic called Shioyama, when with extraordinary suddenness the goddess Amaterasu Ōmikami appeared to her in the unusual form of a mermaid. With her fish tail, the goddess gave Himiko a slap on the cheek, and announced that now was the moment of her true arrival, her true emergence from the cave. The myth recounted in the Kojiki of her iwatobiraki (emergence from the cave) some two thousand years ago was a mere rehearsal of what was now to take place. She emerged now from the dark cave to bring the joyful news that the world would soon be suffused with the light and love of the Mother Goddess. Here was the megamisama no yomigaeri, the resurrection of the goddess; the world was soon to become nyoi-hōju, a wish-fulfilling jewel, [sic] ¶ Her companion, Shioyama, heard the sound of the slap, and of the goddess's voice, but was not sufficiently advanced to see the mermaid avatar. Only Himiko both saw and heard the full revelation." ¶ Himiko changed her name to Ryūgū Otohime, the Dragon Palace Princess. She also had a bronze statue of the mermaid-Amaterau placed inside the cave. Her powers were enhanced after her encounter with the supreme goddess, but she had had experiences before that. "...she had displayed minor psychic powers, experiencing encounters with divinities both in dream and waking vision. Near the Nachi waterfall, for example, in the course of a pilgrimage from Yoshino to Kumano, she had seen the Thirty-six Boys of Fudō Myōō. Now she found that she could both see and converse with all kinds of spiritual beings, both benevolent and troublesome. In consequence, she was now able to heal all types of sickness, both physical and mental, which are caused by invisible spiritual beings. She was able to see the unhappy ghost, or the neglected divinity, who was causing the headaches, the arthritis, the depression, the lethargy, and after listening to its story she could perform the correct ritual for bringing the entity to its due salvation." ¶ But the possessions didn't stop with the mermaid-goddess. Others powerful spirits and goddesses entered Himiko to use her as their human vehicle. Clearly this was going to be a golden age. (Quoted from: Collected Writings of Carmen Blacker, pp. 146-7) For related material see our entries on mermaids or ningyo on our Neko thru Nusa page and on miko on our Kutsuwa thru Mawari-dōrō page.

In the Chinese classic "Journey to the West" the Monkey King can not find a suitable weapon on earth. So, he travels to the palace of the Dragon King who welcomes him accompanied by his 'shrimp soldiers and crab generals'. He offers Monkey a selection of weapons, but none of them seem quite right. The 'trout-captain' had brought out a great sword. The 'whitebait-guardsman' along with the help of an 'eel-porter' displayed a 9-pronged spear. The 'bream-general and carp-brigadier' presented a huge halberd. Although they all have great heft and some are even imbued with magical powers none of them suited this visitors. Exasperated the Dragon King says that he has offered Monkey the best he has. Monkey does not believe him. Finally Dragon Mother reminds her the king of a humongous iron rod which is kept in the treasury. It was the tool used to pound the Milky Way flat. She says: "Just give it to him, and if he can cope with it, let him take it away with him. [¶] The Dragon King agreed, and told Monkey. 'Bring it to me and I'll have a look at it,' said Monkey. 'Out of the question!' said the Dragon King. 'It is too heavy to move. You'll have to go and look at it.... It turned out to be a thick iron pillar, about twenty feet long. Monkey took one end in both hands and raised it a little. 'A trifle too long and too thick!' he said. The pillar at once became several feet shorter and one layer thinner. Monkey felt it. 'A little smaller still wouldn't do any harm,' he said. The pillar at once shrunk again, Monkey was delighted. Taking it out into the daylight he found that at each end was a golden clasp, while in between all was black iron. On the near end was the inscription 'Golden Clasped Wishing Staff. Weight, thirteen thousand five hundred pounds.' " Soon he could wish it to just the right size. Once armed Monkey then extorted a suitable suit of armor out of the Dragon King and his brothers. (Source and quotes from: Monkey, translated by Arthur Waley, pp. 34-37)

Hokusai's Monkey King with the iron staff he got from the Dragon King.

The Monkey King is known in China by the name Sun Wukong (孙悟空).

Much of the story of Urashima Tarō (浦島太郎 or うらしまたろう) takes place in the Dragon Palace. |

||

|

|

||

|

Ryū no tamago |

龍ノ卵 りゅうたまご |

Dragon's egg - "We find the following details in the Shōson chomon kishū (1849). The abbot of the Shingon monastery had a so-called dragon gem (龍ノ玉, ryū no tama), which was considered to be an uncommonly precious object. On cloudy days it became moist at once, and when it rained it was quite wet. In reality it was not a dragon-gem, but a dragon's egg (ryū no tamago, 龍ノ卵). Such eggs are hatched amid thunderstorm and rain; then they destroy even palaces and uproot big trees, and it is therefore advisable to throw them away before-hand on a lonely spot in the mountains. The abbot, however, deemed it not necessary to take this precaution with the dragon's egg in his possession, because it was dead. 'Thirty years ago', he said, 'the egg became moist as soon as the weather was a little cloudy, and its luster was magnificent; but as it afterwards did not show moistness any more even on rainy days, nor grew any longer, it is evidently dead'. MIYOSHI SHŌSON (the author) himself went to the monastery to see this wonderful egg, and gives a picture of it... which shows the dragon fetus inside. Its dimensions were: length, 4 sun, 8 bu; breadth, 4 sun, 6 bu; it was like a " diamond-natured thunder-axe-stone" (玉質雷斧石, gyoku-shitsu rai-fu-seki), called by the people Tengu no ono... or 'Tengu-axe'), but it seemed to be still harder and sharper than these. Its colour was red, tinged with bluish grey, just like the thunder-axe-stones, but its lustre was more like that of glass than is the case with the latter. There were some spots on the egg, which Shosan considered to be dirt left on it by the dragon which produced it." Quoted from: The Dragon in China and Japan by M. W. De Visser, pp. 218-19. |

|

Sagi |

鷺

さぎ |

Heron - Merrily Baird says that "...like other animals of a white color, is considered an emblem of longevity, and from China comes the practice of regarding the bird as a mount of the gods and the Taoist sennin. When paired with the lotus in China, the heron traditionally conveyed a wish for success in the bureaucratic examinations that provided the major means of professional advancement. ¶ Despite its beauty, the heron as a design motif appers infrequently in Japanese art compared to birds such as the crane, plover, and wild goose. This is due partly to the fact that a heron lends itself best to artistic treatment on a large scale, where it is usually the single focus of a design. The limited depiction of herons also reflects an inauspicious connotation, for the word sagi is a homophone for 'fraud' and 'false pretenses.' "

Save for his thin voice The motionless heron Is but a drift of snow

Sōkan (1465-1554)

The photo to the left was posted at commons.wikimedia by Druvaraj S. We found the image of the sagi in the rain at Pinterest. The artist is by Gakusui (1899-1982). |

|

Sagi musume |

鷺娘

さぎ.むすめ |

The Heron Maiden.

Mark Oshima in an entry in the Encyclopedia of Contemporary Japanese Culture (pp. 75-6) says: "Sagi Musume (The Heron Maiden) was reworked under the influence of Anna Pavlova's The Dying Swan. When the dancer playing a woman who is the spirit of the heron would have posed handsomely at the end of the classical version, the modern version has the character sinking slowly to the floor in lifelessness. Other artists rework the classics under the influence of such dancers as Martha Graham. However, for all of these innovations, the main work consists of preserving and transmitting the classics of the past as they have always been performed."

Above is a photo of Anna Pavlova costumed for the Dying Swan. This was posted at commons.wikimedia by Mutter Erde.

In the older versions the Heron Maiden would end her performance standing on a red dais. It was Onoe Kikugorō VI (1885-1949) who gave us the newer version. (Source: Kabuki: A Pocket Guide)

The image to the left is by Kitano Tsunetomi (北野恒富) from 1925. |

|

The Heron Maiden was first performed by Segawa Kikunojō II in 1762 in Edo. It quickly became one of the most important of the dance play repertoire. "...it featured the first use of the revolving stage (mawari butai) for a dance play." ¶ "The Heron Maiden portrays the resentful spirit (onryō) of a heron, who, having assumed the form of a young woman, falls in unrequited love with a man. Five costume changes take place as, before our eyes, we the heron first take the form of an innocent young girl and then an older and more experienced woman. In the end, she is wounded, and, having resumed the form of a heron, dances out her death throes. In short, this play depicts different facets of a woman's psyche, as well as a kind of montage of both human and avian identity." (Source and quotes: Kabuki Plays on Stage: Brilliance and Bravado, 1697-1766, pp. 316-7) ¶ In many of the printed images the Heron Maiden is carrying an umbrella. "The play's meaning is clear enough.... the maiden's umbrella... symbolize[s] the wheel of karma, driving the dancer into the jaws of hell in retribution for her wrongful attachment to a man. One can only pity this spirit and feel that her fate was excessively cruel." Because of this the segment of her torture in hell has been shortened for modern audiences. (Ibid., p. 318) [Onryō is 怨霊].

Above is a detail from a print by Harunobu showing an actor in a theatrical performance.

"A further expression of great emotion may be seen in both dances and plays when the actor performs the exaggerated pose called the ebizori [蛯反り]. This involves bending the body backwards from a kneeling position into a shape resembling a prawn (ebi). These poses are usually performed by animals and creatures of the other world at times of extraordinary stress or emotion. The heron maiden in Sagi Musume performs and ebizori when describing the excessive tortures of hell." (Quoted from: A Guide to the Japanese Stage: From Traditional to Cutting Edge, p. 87) ¶ "The current version is based on a revival of 1892 by Ichikawa Danjūrō IX when the hikinuki costume changes were first introduced." (Ibid., p. 132) The dance illustrates "...the Buddhist doctrine that emotional craving and attachment to this world will keep one from salvation." (Ibid.)

Costume changes are important for the role of the Heron Maiden. Earle Ernst wrote in The Kabuki Theatre (p. 186): "In the costume change called hiki-nuki ('pulling-out') the parts of the outer kimono are basted together and when the threads are pulled out by a stage assistant the outer costume falls from the body of the actor. This change, usually employed in dances, shows a change of mood rather than a change of character. In the dance White Heron Maiden the heroine changes costumes four times in this fashion to show the passing of the seasons of the year." Hikinuki is 引抜き

James Michener said that the Heron Maiden is also referred to as the spirit of the snow.

Horikoshi Nisōji (壕越二三治: 1721 to ca. 1781) wrote a number of tokiwazu (常磐津) - a type of music created in ca. 1739 and meant to accompany a performance - danced dramas for the theater. Despite his importance within the theatrical world and all of his innovations his Sagi Musume is the only work which has survived according to Samuel L. Leiter. Kabuki Plays on Stage: Brilliance and Bravado, 1697-1766 says that the author of the play performed today is anonymous.

Among other artists who have created prints on this theme were Harunobu, Bunchō, Shunshō, Koryūsai, Utamaro, Chikanobu, Kunichika, Kunisada, Yoshitoshi, Kunimasa III and Toshihide. |

||

|

|

||

|

Saigō Takamori |

西郷高盛

さいごう.たかもり |

One of the leaders who helped overthrow the Tokugawa regime and place the Meiji Emperor at the head of government in 1868. He died in 1877 in the Satsuma Rebellion (西南の役) against that same regime.

The image to the left is from a photo taken by Fg2 and posted at commons.wikimedia. The statue made in 1898 by Takamura Kōun (高村光雲: 1852-1934) is in Ueno Park. Below is a doctored version of a print by Yoshitoshi from 1878 in which the ghost of Saigō has returned with a letter he wants to deliver.

For a bit of interesting information about Saigō Takamori see our entry on hoshi on our Hoshi thru Hotaru page. |

|

|

||

|

Saikaku |

犀角

さいかく |

Rhinoceros horn cup: one of the "Myriad Treasures" which are said to have protective qualities. Of Chinese origin. 1

One source says that the "8 Treasures", another name for the "Myriad Treasures", was first used during the reign of the Yuan Dynasty in China. Please note that the "8" aren't always the same items. Sometimes there is no rhinoceros horn among them.

The Chinese believed in the mystical powers of rhinoceros horns. They could either act as an aphrodisiac when ground into a powder or if carved and polished into libation cups they could prevent poisoning because of their supposed sensitivity to mercury. (They also promoted the idea that one couldn't be poisoned if one ate off of celadon plates because either the porcelain would 1) discolor or 2) scream out to the potential victim right before he is about to ingest the tainted food. One has to wonder how many people died believing this. It reminds me of the slaughter of natives at Wounded Knee where the warriors thought they had been either made invisible or invincible. I don't remember which.) ¶ According to Grahame Clark in his Symbols of Excellence: Precious Materials as Expressions of Status (Cambridge University Press, 1986, p. 22) notes that images of the rhinoceros appear as early as decorations on Shang bronzes, but "The earliest artefacts made from rhinoceros horn to survive are some plain wine cups in the Shoso-in collection at Nara dating from the Tang dynasty."

Ctesias of Cnidus, a 5th century B.C. physician, said it was only the horn of the unicorn which protected people from poisonings and insured good health.

Source: "Chinese Clay Figures", by Berthold Laufer, Published by Field Museum of Natural History, 1914, p. 75, footnote 2. This section is called "History of the Rhinoceros".

Our word 'rhinoceros' means 'nose horn'. (Ibid., p. 88) |

|

The first Japanese reference to the rhinoceros came from the Buddhist monk Chōnen (奝然) when he traveled to China in the late 9th century. When writing of the animals found in Japan he included rhinos and elephants, but there were no such animals native to his homeland. Why then did he mention them? Perhaps he meant them metaphorically. That is what some scholars think. Other scholars think it was a transcription error and that Chōnen had actually said that there were no rhinos or elephants in Japan. But this is unresolvable and hence moot. (Ibid., pp. 89-90)

When the Emperor Shōmu (聖武) died in 756 his Empress deposited his treasures, including the rhinoceros horn cups, in the Shōsōin (正倉院). The concept of the horn as an aphrodisiac was a Taoist belief which has persisted until today. Both the Taoists and the Buddhists use it as one of the '8 treasures'. In the 4th century Ge Hong was "...said to be the first to draw attention to the tongtian rhinoceros horn, 'giving passage to heaven', which enabled the wearer to travel under and through water." It was also believed to function as a panacea. ¶ Friedrich Hirth said that carved rhinoceros objects were being imported into China from the Roman east and India as early as the 5th century.

Source and quotes from: The Arts of China to AD 900, by William Watson and Chuimei Ho, Yale University Press, 1995, 75.

Since horn is strongly fibrous ivory is easier to carve. This makes for differences in the end results of the two materials. (Ibid.)

Robert Beer in his Handbook of Tibetan Buddhist Symbols (Serindia Publications, Inc., 2003, p. 48) tells us that "In Chinese medicine the rhinoceros horn is known as 'dragon's tooth', and as a phallic symbol of erect virility it is highly esteemed..." Goofy me, that thought hadn't even occurred to me.

It would seem that the representation of a couple of rhino horns in Chinese is described by a character which is homophonous for another character which mean 'happy'. |

||

|

Sai no kawara |

賽河原 さいのかわら |

Children's Riverbed Hell: "Seven- and eight-year-old children held hands with three- and four-year olds, all of them stricken with inexpressible grief. 'What’s the meaning of this?' Nitta asked, taking in the sight. The Bodhisattva explained: 'These are children who died without compensating their mothers for the pain they caused them during their nine months in the womb. They’re to suffer on the riverbed like this for nine thousand years.' A blazing fire swept the expanse, and the stones all burst into flames. As the children had nowhere to run, they were burned up until only their ashen bones remained. Soon, a number of demons arrived. Shouting 'Arise! Arise!' and beating the ground with iron staves, they restored the children to their former selves." Quoted from Keller Kimbrough's translation of The Tale of the Fuji Cave.

In an essay on Beckett and the Japanese Theatre the author Carol Fisher Sorgenfrei compared three of the characters in Endgame to the children of Sai no kawara. "In Japanese folk belief, children who die before the age of ten exist in a state of eternal purgatory called sai no kawara. There they build prayer pagodas for their parents , only to have the demons daily knock the rock structures down. Thus, even innocent children are prevented from helping the ghosts of their parents through filial prayers." |

|

"The beliefs and practices I have described reflect changes that took place at the beginning of the Tokugawa period in the way infants were regarded. In earlier times, children who died before they reached the age of seven did not have to be buried because they were not yet entirely “human”; they were considered closer to deities or to the other world. It was only from the late Muromachi and early Tokugawa periods that children really came to be viewed as human, as we can see from their appearance in illustrated hell scrolls of a type of hell or limbo specifically for small children that took the form of a dry riverbed and was known as sai no kawara 賽の河原. The gradual incorporation of infants and children into pacification rituals is seen in Shiryō gedatsu monogatari kikigaki 死霊解脱物語聞書 (Stories Heard about the Salvation of Dead Spirits, first published 1690, first illustrated edition 1712). In this Buddhist tale, which illustrates the priest Yūten’s holy powers and features his exorcism of the famous ghost Kasane 累, Yūten gives a Buddhist name to the spirit of a sixyear-old boy drowned in a lake by his parents." Quoted from: 'The End of the “World”: Tsuruya Nanboku IV’s Female Ghosts and Late-Tokugawa Kabuki' by Sataoko Shimazaki in the Monumenta Japonica 66/2, p. 221. |

||

|

|

||

|

Sajiki |

桟敷

さじき |

The gallery of a theater.

"As plays grew in complexity during the eighteenth century , so did architectural arrangements of kabuki theatres, which by the 1720s were roofed structures seating up to 1,000 spectators. Access to expensive seats in two tiers of box seats (sajiki) that lined the sides of the playhouse was through adjoining theatre teahouses (shibai jaya), which provided not only theatre tickets but food and drink and a place to rest during an all-day performance."

Shibai jaya is 芝居茶屋.

Quoted from: The Man who Saved Kabuki: Faubion Bowers and Theatre Censorship in Occupied Japan, by Shirō Okamoto, University of Hawaii Press, 2001, p. 3. This quote is from the introduction by Samuel L. Leiter and James R. Brandon. This quote also appears in Kabuki Plays on Stage: Brilliance and Bravado, 1697-1766, Brandon and Leiter, University of Hawaii Press, 2002, p. 3. |

|

Lighting and the sajiki in early kabuki theaters is discussed in Crosscurrents in the Drama: East and West edited by Stanley Vincent Longman (University of Alabama Press, 1998, p. 33): "The chief source of kabuki lighting from the 1720s or 1730s was actually from removable sliding doors (madobuta or akari mado) high up over the left and right galleries (sajiki), where theatre workers manipulated the amount of daylight streaming in."

The above quote is from the essay entitled "From London Patents to the Edo Sanza: A Partial Comparison of the British Stage and Kabuki, ca. 1650-1800" by Samuel L. Leiter.

Madobuta is 窓蓋; Akaru mado is 明かり窓.

"The seat at the back of all , where the police or representative of the Government sits, is the Tsoombo Sajiki - i.e., the deaf-box, where they are supposed to see only and not to hear."

Quoted from: Gleanings from Japan, by Walter G. Dickson, published by W. Blackwood and Sons, 1889, p. 53.

Dickson's 'Tsoombo Sajiki' was the tsunbosajiki (聾桟敷) or upper gallery or blind seat. 聾, tsunbo, means deafness or a deaf person.

Gregory M. Pflugfelder in his Cartographies of Desire: Male-male Sexuality in Japanese Discourse, 1600-1950 (University of California Press, 1999, p. 118) notes that there was a government edict in 1668 which forbid sexual contact between actors and patrons within the theater during performances and stipulated that sajiki were not to be "...outfitted with hanging blinds so as to screen out the regulatory gaze."

Joseph Henry Langford in his Japan of the Japanese (published by Scribner, 1914, p. 162) noted that sajiki "...are the best and most expensive seats..."

Nancy G. Hume (Japanese Aesthetics and Culture: A Reader, SUNY Press, 1995, p. 203) states that when kabuki theaters evolved into more substantial structures that sajiki were added to provide spaces for customers who wanted more comfort and privacy. She added that "Boxes of the first tier were known as quail boxes (uzura sajiki [鶉桟敷]) because their wooden bars made them resemble crates for keeping quail. ..." (Ibid., p. 207)

Centuries before the use of the word sajiki to stand for 'boxes' it meant 'viewing stand'. Jacob Raz (Audience and Actors: A Study of Their Interaction in the Japanese Traditional Theatre, published by the Brill Archive, 1983, p. 49) notes that in the early 12th sajiki - he calls them 'special raised seats' - were built for festival viewing by warriors. "As for the audience's seats, we can see that though sometimes, particularly when performances were held at nobles' mansions, members of the upper classes were provided with higher seats, and later with especially built sajiki, the bulk of the audience was still in the same space and on the same level as the performers." (Ibid., p. 50) A diary from the 15th century stated that "...the sajiki seats were thirty to fifty times as expensive as the ground seats." (Ibid., p. 75) In modern theaters the better seats tend to cost 5.7 times more for kabuki or 3 times for noh. (Ibid., pp. 77-78) Hence, the sajiki seating started out as an elitist privilege because only the wealthy could afford it. (Ibid., p. 78) The fees charged by temples and shrines went to "...repairing and rebuilding..." (Ibid., p. 76) Some early sajiki were constructed privately for exclusive usage. (Ibid., p. 81) By the time of the Taiheiki in the 14th century the shōgun's party might occupy up to five boxes, while lesser nobles would reserve fewer seats and sometimes special sajiki would be for upper class women who would be hidden behind curtains of thin cloth so they could see out, but others could not see in. (Ibid. p. 83) ¶ By the early 15th century sajiki were occasionally dealt with somewhat differently: "It is recorded that priests used to hire sajiki there and send the bills to their shrines, which recognized them as expenses. This new custom of playgoing on the expense account spread to other places, and it became common for officials to recover their sajiki expenses." (Ibid., pp. 84-85) ¶ "Generally speaking, the theatre was divided into sajiki and doma [ground level]. As time passed, both sajiki and doma became more complex and subdivided. By the Genroku period [1688-1703], the sajiki was already divided into kami (upper [上]) sajiki and shimo (lower [下]) sajiki..." The lower levels were also broken up into different groupings on occasion. The sajiki were not only connected physically to teahouses, but also to the dressing rooms of the actors. After a series of raucous parties the government ordered in 1723 that the sajiki passageways be removed. "A spectator may not call upon an actor or see the actor in a tea-house. It is also illegal to see an actor at his residence." (Ibid., p. 171) [No wonder so many people skulked around hiding their faces under hoods or oversized woven hats.] ¶ "As mentioned before, rich samurai would often come to the theatre and sit in the sajiki, at the invitation of wealthy merchants who had business contacts with them. During the third moon, when the ladies-in-waiting had their annual vacations, they would also come to the theatre and, like the samurai, surreptitiously occupy the sajiki. The bakufu's regulations for the theatre therefore ordered that 'hanging bamboo blinds in the sajiki is prohibited. Curtains and folding screens in the sajiki must also be removed'. The first part of the order was intended to prevent the samurai and ladies-in-waiting from hiding behind the bamboo blinds; the second meant that the increasingly decorated sajiki irritated the bakufu. These two orders, like their predecessors, were not followed. [¶] Sajiki patrons included a popular type of spectator called kabesu - a word made up of the first syllables of kashi (cake), bento (lunch box), and sushi (vinegared fish and rice). This patron, who did not want to miss a scene, would have meals sent to him from the tea-house, and would watch the whole performance while eating." (Ibid., p. 172) [¶] "At the very back of the theatre was the ōmukō ('great beyond') or mukō-sajiki, and the rearmost seats in this part were called tsunbo-sajiki ('deafman's sajiki'), as it was almost impossible to hear the dialogue." (Ibid.) |

||

|

Sajiki |

歳時記 さいじき |

Almanac of seasonal words, often for haiku poets. This linking of words to seasons was first established in the Kokinshū (古今集) in the early 10th century. |

|

|

||

|

Sakaki |

榊

さかき |

Sacred Shinto tree. There are a couple varieties of evergreen shrubs referred to as sakaki or may be a description of one of three species of trees - pine, cedar or oak. As a shrub it has dark, narrow glossy leaves with fragrant flowers and black fruit. It is used in a number of ritual ceremonies and at times is intentionally set afire.

Mentioned in the Nihonga as being decorated with jewels, a mirror and cut paper. (See tamagushi)

The image to the left is that of the Japanese cleyera. It is from the web site of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. Brian Bocking in A Popular Dictionary of Shinto (p. 149) says "Sakaki generally means cleyera ochnacea or theacea (japonica)." The article in the Encyclopedia Britannica indicates it could be either cleyera japonica or ochnacea.

Sakaki are used in the Aoi Matsuri (Hollyhock Festival). "Sakaki toru (break off evergreen boughs) is a summer seasonal word; one breaks sacred sakaki boughs from Kamiyama 神山 mountain to prepare for the Aoi festival of the Kamo shrines in the middle of the fourth month." (From footnote 80 of The Journal of Sōchō.) |

|

Sakoku |

鎖国 さこく |

A self-imposed ban on contact with foreigners instituted in 1653 by the Tokugawa regime in 1653. "There were, however, some exceptions to the sakoku. Besides contact to the Asian continent, there was still contact to Europe via the Dutch traders. This contact was 'restricted to the small artificial island of Dejima in Nagasaki Bay', but the bi-annual visits of the Dutch traders were an important chance for the shogun and Japanese scholars to gain access to information on world affairs and new developments." English in Japanese Language and Culture: A Socio-Historical Analysis by Kai Hilpisch, p. 8. |

|

"What started as early as the 1640s as a curiosity about Western medical practice grew during the eighteenth century into a profound interest in Western science and technology in general. In 1800, for instance, Shizuki Tadao [志筑忠雄: 1760-1806], the pioneer who introduced the principles of Western linguistics to Japan, wrote an introduction to Newton's work in physics and astronomy on the basis of John Keill's Inleidinge tot de waare natuuren sterrekunde (Introduction to the True Natural Science and Astronomy) of 1741. ¶ Shizuki was the same author who invented the term Sakoku ('closed country') while translating Engelbert Kaempfer's chapter on the question of Japan's right to 'stand off' from other nations and turn its back on international relations." Quoted from: Visible Cities: Canton, Nagasaki, and Batavia and the Coming of the Americans by Leonard Blusse, p. 49.

"In some sense the very consciousness of the system [i.e., sakoku] came rather late and, as Ronald Toby points out, was a product of the Dutch influence. The sakoku was coined by Shizuki Tadao in 180I when he was ordered to translate Kaempfer's defense of the system by the authorities." Quoted from: Rangaku and Westernization by Marius Jansen in Modern Asian Studies, 18, 4 (1984), p. 541. |

||

|

|

||

|

Sakura |

桜

さくら |

Cherry blossom motif used as a family crest or mon: This flower is the most frequently mentioned in Japanese literature. It was first mentioned in 712 A.D. in the earliest known writings. In the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan entry by Matsuda Osamu (vol. 1, p. 268) the cherry blossom's popularity in Japan is contrasted with the Chinese fascination with the flashier peony. Because the cherry flower is more delicate and short lived it suits the Japanese aesthetic and sense of temporality better. In the 8th century Man'yōshū, an anthology of poems, the plum blossom is mentioned more often than that of the cherry, but this probably shows the strong influence of Chinese literature. However, by the Heian period the general word for flower, hana, came to mean the cherry flower. Motoori Norinaga (本居宣長 - 1730 to 1801) wrote that all one had to do was smell the fragrance of the cherry blossom in the early morning 'to know the essence of the Japanese spirit.'

As a family crest the sakura was not as popular. Perhaps its delicacy dictated against a more martial use. |

|

Samegawa |

鮫皮

さめがわ

|

Ray skin used as both a decorative and practical covering for the hilt of a Japanese swords. (See our entry for tsuka.) Like so many other things in this world there seem to be a lot of misconceptions around this material. Generically it is referred to in the West as sharkskin, but this may not be true. Either way this is what I was told and believed in 1984 and only recently have learned otherwise. Another misconception came in a conversation I had with a fellow recently. I told him I was going to add an entry on samegawa into this site and he said something like: "Oh, that stuff is so common." Well...that may be true for those who are interested in looking at Japanese swords, but if you look a little more closely you will realize that this material was used much more selectively than one would think today. Obviously samegawa was applied to the sword hilts of the elite and ruling classes because it must have been fairly costly in its gathering, processing and application.

The word used in English for samegawa is shagreen. Based on a French term meaning 'rough skin' it came by extension to a close relationship with the word chagrin. |

|

Samurai |

侍 さむらい |

"The sixteenth century was the golden age of the old-style samurai, the jizamurai, as they are often called: the men who lived out in the countryside, on fiefs with which they had long associations and over which they exercised a substantial degree of independent control, dispensing rough and ready justice, gathering taxes, and mobilizing the inhabitants for the tasks of both war and peace." ¶ The samurai were "... a constant dilemma..." for their local daimyōs who needed their support in dangerous times, but had to negotiate with them to keep it and thus diminished their own power. Samurai were free enough to change sides if they were displeased or even raise their own militias against their local overlord. (Source and quotes from: Warrior Rule in Japan by Marius Jansen, pp. 206-7)

Under the Tokugawa shogunate "All castle-town samurai had to serve at one time or another in Edo, where their bills could only be paid in cash, and it was not long before the money economy spread to provincial towns and villages as well. (Quoted from: The Meiji Restoration by William Beasley, p. 44) See our entry on jōkamachi for more on the castle towns. |

|

Sanbasō or sambasō |

三番叟

さんばそう |

"Awaji puppet performances can be divided into two broad categories according to whether the targeted audience is divine or human. In practice, however, the audience often consists of both deities and humans. Performances intended for deities (shinji, 'sacred matters') have human beings as "onlookers" and even sponsors. The two examples of these sacred rites in the Awaji tradition are the Sambaso rite, used as a purifying ceremony and invocation of the deity's blessing at events inaugurating something - from new rice-paddy dikes to a marriage— and the Dance of Ebisu, a lively performance enacting the life and love - namely, sake - of Ebisu, the deity of fishermen and shop owners." Quoted from: Traditional Japanese Theater: An Anthology of Plays, edited by Karen Brazell, The Awaji Tradition by Jane Marie Law, pp. 394-95.

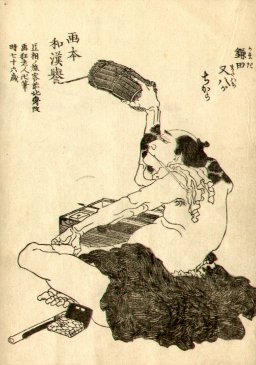

The image to the left on top is from the Walters Museum of Art in Baltimore. I found it at commons.wikimedia. The image shown above comes from Ursinus College and was posted at Flickr. The print by Kuniyoshi shows an actor as a sanbaso marionette and comes from the Lyon Collection. Click on it to go to the page devoted to it. |

|

"During the Tokugawa period, every kabuki program began at dawn with a sophisticated ritual dance featuring the character of Sanbasō. Performed by a low-ranking actor, the dance was built around three short scenes (dan): 'waving sleeves and stamping' (momi no dan), the conventional 'jumping like a crow' (karasutobi), and the 'bell-tree' (suzu no dan), in which the dancer shakes a wand covered with small bells. It would be hours before the major stars appeared and the main play began, so only the most determined fans would attend. Today the dance is performed regularly for the New Year's production, and occasionally at other times as well. ¶ Kabuki's various Sanbasō dances have their origin in the ritual nō play Okina, which in turn derives from early agricultural rituals intended to ensure prosperity. 'Okina' means 'old man,' and the central character symbolizes longevity and eternal youth. Okina exhibits many features that are different from nō proper, marking it as sui generis: the main actor (shite) puts on his mask in front of the audience; the steps at the front of the stage are used for an entrance; the music includes percussion patterns not found in any other nō play; and the dance has no plot. The nō performance begins with Senzai, played by the secondary actor (waki), taking the Okina mask from a small onstage altar. After the shite dons the Okina mask, he performs a short, solemn dance and leaves the stage. An actor of comic kyogen roles playing Sanbasō then dances a light-spirited imitation or parody of Okina's movements. Sanbasō is known as the 'black Okina,' since he wears a black version of the old-man mask." Quoted from: Kabuki Plays on Stage: Darkness and Desire, 1804-1864, p. 52. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

三本傘

さんぼんからかさ |

A triple umbrella motif most often associated with the kabuki character Nagoya Sanzaburō. Originally the umbrella, an importation from China during the Heian period, was considered a luxury good. Therefore the representation of the umbrella was meant to convey superior status. There were also two Japanese families that used the three umbrellas as their family crest: the Mure (牟礼) and Magaribuchi (曲淵).

The image to the left is from the collection of the Fitzwilliam Museum. It is a surimono by Kunisada. |

|

Sanemori Monogatari |

実盛物語 さねもり.ものがたり |

An alternate name for the kabuki play Genpei Nunobiki no Taki. 1 |

|

Sangi |

算木

さんぎ |

Divination rods: "In sangi divination, six square sticks with all four sides differently marked were used to tell fortunes. In sangi calculation, several hundred short sticks colored either black or red were laid out in a prescribed manner and used to perform either addition or subtraction." Several families used the sangi as a family crest or mon because of the augury of its being an auspicious sign.

Remember: There are numerous variations on this motif used as family crests. |

|

Sango |

珊瑚

さんご Above is a detail from the sleeve of the robe of a courtesan. Below is an example of living red coral posted at commons.wikimedia by Nick Hobgood.

|

Coral - often portrayed among the Myriad Treasures or takaramono (宝物). Sango is considered one of the seven precious things brought to Japan on the takabune (宝船). The seven vary according to different accounts. One group includes lapis lazuli. Some sources say they are "...gold, silver, coral, crystal, agate, emerald and pearl..."

Occasionally the term sangojū (珊瑚樹) is used. It describes a branch of coral.

Above is a piece of coral posted by Gryffindor at commons.wikimedia. It is from the collection of the Natural History Museum, Vienna.

The importation of coral was banned in 1668. Source: Asian Material Culture, essay by Martha Chaiklin, p. 51.

|

|

Sanko |

三鈷杵

さんこ |

A three-pronged vajra. The sanko shown below is from the collection of the Brooklyn Museum. See also our entry on kongōsho.

There is a story that while Kūkai was in China he threw a three-pronged vajra. It landed in a pine tree in Japan where the Shōryū-ji (青龍寺) was established. The three story pagoda there was posted at commons.wikimedia by Reggaeman. There is a similar story about a thrown dōkko. |

|

Sanmaitsuzuki |

三枚続 さんまいつづき |

A Japanese woodblock print triptych or three-panel composition. (See also ichmai-e and nimaitsuzuki.) |

|

Santō Kyōden |

山東京伝 さんとう.きょうでん |

Major popular author who lived from 1761-1816. He originally was successful as the Ukiyo-e artist Kitao Masanobu. 1 |

|

Sanzu no kawa |

三途の川 さんずのかわ |

A river which flows into Hell and is the final separating barrier for souls of the deceased between the temporal world and their damnation. |

|

Saru |

猿

さる |

Monkey. This is also the creature used as the ninth symbol of the zodiac, but in that case the character used is 申 although it too is pronounced 'saru'. 1, 2 |

|

|

猿回し さるまわし |

Monkey trainer |

|

Sasa |

笹

ささ |

Bamboo grass: "...the Japanese term for [a] species of bamboo that grow to only one or two meters. Although less frequently used in painting formats... bamboo grass is especially well suited for presentations in crest and textile designs..."

Quoted from: Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design, by Merrily Baird, p. 72. |

|

Sasabeni |

笹紅

ささべに

|

"Bamboo grass" rouge is the name for the application of rouge over charcoal on the lower lip causing the lip to appear green. This was a fashion statement. 1

"...pure Carthamin... has a metallic, gold-green lustre, reminding one of certain aniline dyes and the sheath-wings of several species of... beetles. The Japanese girls dissolve it in water for reddening their lips. In Kiōto they often put it on so strong and concentrated that the green metallic lustre appears instead of the red colour."

Quoted from: "The Industries of Japan: Together with an Account of Its Agriculture, Forestry, Arts, and Commerce" by Johannes Justus Rein, 1889, p. 177.

See also our entry on benibana on our Aoi thru Bl index/glossary page.

There is also more information to be found on one of our pages devoted to a Kunisada print. |

|

The image of the Hiroshige from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston shown above, Komagata Hall and Azuma Bridge (Komagata-dō Azuma-bashi), shows a red flag, which is a sign of a beni-ya or beni shop, where a person could purchase more of this cosmetic. One small cup full required approximately 2,000 safflowers and would allow for about 50 single-layer applications. It would take about 1/3 of a cup to get the desired iridescent green. According to Sawako Takemura Chang, if one could not afford the more expensive sasabeni then the lower lip could be painted with sumi ink first and then covered with over with ordinary beni giving a bluish tint.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Sasarindō |

笹竜胆

ささ.りんどう |

Dwarf bamboo and bellflower crest of the Murakami (村上 ) branch of the Minamoto ( 源), i.e., the Genji clan.

Surimono by Kunisada in the collection of the Havard Museums.

|

|

Sashimono |

指物

さしもの |

A banner worn on a pole attached to a soldier's back, for easy identification. The example shown below is from the 18th to 19th century. It is on silk and created long after the need for wartime battles. It comes from the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

"One of the most striking features of Japanese armour of the period was the sashimono, a long banner worn from a crossbar and pole arrangement attached to the back of the armour. These banners were marked with the mon, or crest, of the commander of the samurai's unit. Naturally, Lords didn't usually wear sashimono; they had standards and standard-bearers. The banners of different units within an army could be similar, to provide instant recognition. (In Akira Kurosawa's films Ran and Kagemusha, these banners are in evidence in all battle scenes; in reality there would have been thousands.)" Quoted from: Sekigahara 1600: The final struggle for power by Anthony J Bryant. |

|

Sawamura Gennosuke II |

沢村源之助

さわむら.げんのすけ |

|

|

|

四代目沢村源之助

さわむら.げんのすけ |

Kabuki actor 1859-1936.

Below is one of the mon that he wore. It shows three gingko leaves forming a circle.

|

|

Sawamura Sōjūrō IV |

沢村宗十郎

さわむら.そうじゅうろう |

Kabuki actor 1784-1812. 1 |

|

Sawamura Sōjūrō V |

(

( |

Kabuki actor (1802-53). This is the same actor as Sawamura Gennosuke II (see above). He became Sōjūrō V in 1844.

Lyon Collection Sōjūrō V from 1847

|

|

Sawamura Tanosuke II |

澤村田之助

さわむら.たのすけ |

Kabuki actor (1788-1817). 1 |

|

Sayagata |

紗綾形

さやがた |

A decorative motif of interlocking manji or swastikas. This pattern is remarkably prolific in ukiyo prints although often it is not immediately obvious. |

|

Schwaab, Dean J. |

|

Author of Osaka Prints 1 |

|

Sedai |

世代 せだい |

Generation |

|

Segawa Kikunojō V |

瀬川菊之丞 せがわきくのじょう |

Kabuki actor 1802-32

Segawa literally means 'shallow river.' 1 |

|

Seigaiha |

青海波

せいがいは |

A decorative motif composed of partially concentric circles stacked to represent waves.

This word literally translates as 'blue ocean waves' although the wave pattern does not necessarily have to be in blue. Above is a detail from a lacquer box by Shibata Zeshin (柴田是真: 1807-91) at the Met. Their curatorial files state: "The combed pattern on the waves illustrates Zeshin's revival of the "blue wave" (seigaiha-nuri) technique, in which lacquer thickened with egg white or clay is placed on a surface and then combed into a pattern with a bamboo brush."

It is also said of Zeshin that "He resucitated the once supposed lost style of the Seigaiha 青海波, and also invented the art of painting with lacquer on paper or on silk." Quoted from: Kokka, Issues 212-216, 1908, p. 285. |

|

Seigle, Cecilia Segawa |

|

Author of Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan 1

In 1994 Lawrence Rogers wrote of Ms. Seigle's book on the Yoshiwara that "This scholarly work is the definitive monograph in English on the Yoshiwara in premodern times." |

|

LINKS TO OUR OTHER INDEX/GLOSSARY PAGES Click on any of the pages listed below!

|

||

HOME

HOME