JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画

formerly of Port Townsend, Washington |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

Nehanzō thru Nyūdō |

|

|

The molecular model on Lonsdaleite is being used as a marker for new additions from January 1 to May 31, 2021. The piece of sulphur posted at Wikimedia by Rob Lavinsky was used from June 1 thru December 31, 2020.

The detail from the diadem of

the Empress Eugénie |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Nehan, Nehanzō, Neko, Nekomata, Nengō, Neoi, Nerikawa, New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of kabuki jiten,

Nigimitama, Nihachi, Nihon zutsumi, Nijūshikō, Nikkō, Nimaistuzuki, Ninja, Niō, Nise Murasaki inaka Genji, Nishiki-e, Niwaka, Nobori, Noh, Nokori-enogu,

Norimono,

Nunobiki, Nunomezuri, Nurude,

Nusa,

Nushi, Nyoi-hōshi,

Nyonin kinsei, Nyūdō

涅槃, 涅槃像, 猫, 猫又, 年号,

根生, 練革,

和魂, 二八, 日本堤, 二十四行孝, 日光, 二枚続, 忍者, 仁王, 偐紫田舎源氏, 錦絵, 俄, 幟, 能, 残り-絵の具,

乗り物,

布引, 布目摺, 白膠木, 幤, 主, 如意宝珠, 入道 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

Nehan |

涅槃 ねはん |

Nirvana or Buddha's passage to spiritual existence |

|

Nehanzō |

涅槃像 ねはんぞう |

Death of Buddha picture -

"Paintings of the death of Buddha, called in Japan Nehanzō (Nehan

means Nirvāṇa and zō means image) are not so numerous in Japan's

Buddhist art, in comparison to paintings of Amida, Jizō etc."

The image to the left is

from the Lyon Collection. Click on it to see an enlargement of it for better

viewing. |

|

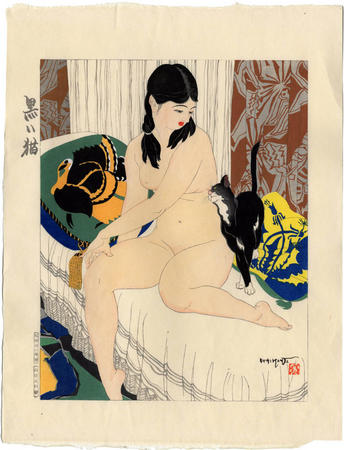

Neko |

猫

ねこ |

Cat(s): Also an affectionate term for a geisha. (See our entry on shamisen.)"

The character used for cat in China is the same as the one used by the Japanese - 猫. However, in China it is referred to as a mao "...given to it in imitation of its mewing, but the composition of this name is intended to express an animal which catches rats in grain. [The italics are those of the author C.A.S. Williams.]

Chinese characters are often created from the combination of certain basic elements, but I am not one who is accomplished at parsing these. The left hand element (i.e., the radical) which means 'dog' or 'animal' works well with the right hand element which means 'seedling' when standing alone.

I want to thank our great contributor Eikei (英渓) for helping me with a clear understanding of this kanji character. |

|

Many sources claim that cats arrived in China at the same time as Buddhism. However, the Kodansha Encyclopedia entry is not that specific. "The domestic cat (Felix catus) was introduced to Japan from Korea and China in ancient times, although there are no reliable records as to the precise date or route. Judging from historical records which note that a black cat was presented to Emperor Kōkō (830-887; r 864-887) from China and that one was presented to Emperor Ichijō (980-1011; r 986-1011) from Korea, it may be gathered that the cat was still a rare and highly prized animal in the 9th and 10th centuries. It is believed to have become fairly common by the close of the Heian period (794-1185). As a rule systematic breeding has not been practiced in Japan, but the variety known as the Japanese cat has since ancient times been described as a white hort-haired cat with black and brown spots. Cats with long tails were once favored, but from the latter half of the Edo period (1600-1868) those with stubby tails became popular." This entry was written by Imaizume Yoshiharu.

There a plenty, even oodles, of Japanese representations of cats which are just cats. One such example is the Ishikawa Toraji (石川寅治) print below.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Nekomata |

猫又 or 猫股 ねこまた |

A mythical two-tailed monster cat.

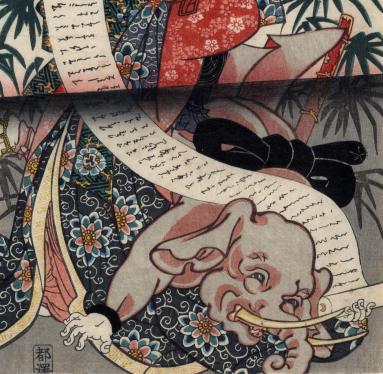

To the left is a woodblock print by Kuniyoshi (歌川国芳) from the Lyon Collection. Click on it to learn more.

A Kyōsai preparatory drawing of a nekomata. |

|

Nengō |

年号 ねんごう |

"NENGŌ, or 'ERA-NAMES', represent the principal Japanese method of dating from early times to the present day. Prior to the Meiji Restoration of 1868 they were often used independently from the reigns of individual Emperors, being changed by the Bakufu authorities more or less at will (sometimes, simply to indicate a hoped-for change of luck after a 'Cabinet reorganization' or natural calamity). ¶ Of the thirty-six nengō of the Tokugawa Period (1600-1868) some were as brief as a year or two, others extended over two decades. The more famous nengō: Kan-ei, Genroku, Kansei, Tempō - have come to represent and embody the characteristics of their times..." Quoted from: "Historical Eras in Ukiyo-e" by Richard Lane in Ukiyo-e Studies and Pleasures, Society for Japanese Arts and Crafts, the Hague, 1978, p. 27. |

|

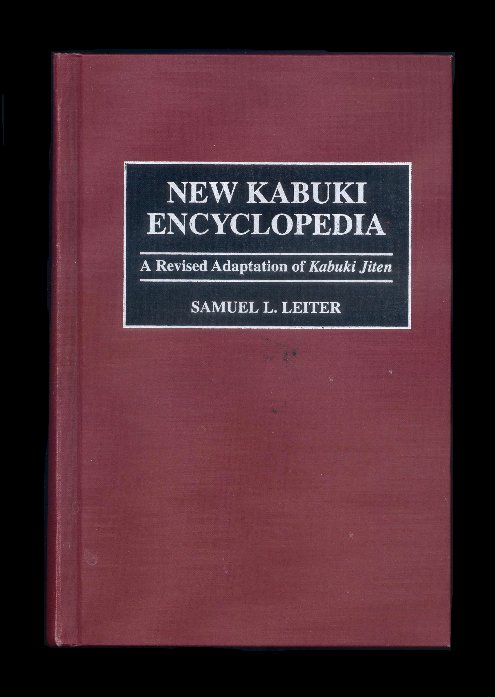

Neoi |

根生 ねおい |

"'Root-born,' an actor who is a true-born son of a vicinity where the generation of his ancestors lived and where he has acquired patrons... For example, it is common to refer to one of the Ichikawa Danjūrō line as an Edo neoi [江戸根生] actor."

Quote from: New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of kabuki jiten, by Samuel L. Leiter, 1997, p. 466.

I am speculating here, but it would seem to me that judging from other observations of crowd behavior show an almost irrational attachment to hometown heroes. This would have probably been even more pronounced with kabuki because there were major differences in performing styles between actors from Edo - rough and tumble - and that of Osaka - more delicate, more feminine. Fan loyalty in this case carries a geographic element to it to boot. |

|

Nerikawa |

練革 ねりかわ |

Worked rawhide: "Quality was the greatest distinguishing feature between these early schools, but over the centuries this would change to include other features such as the shape and style of helmet bowls that they produced and the manner in which they fabricated them. The Iwai, for example, one of the oldest of these guilds were renowned for the items of armour that they made from rawhide, or nerikawa. |

|

New Kabuki Encyclopedia: A Revised Adaptation of kabuki jiten |

|

A major source book compiled by Samuel L. Leiter, but a bit confusing in its descriptions. 1 |

|

|

鼠木戸

ねずみきど |

Literally a 'mouse door' - Samuel L. Leiter wrote in reference to 'The Kanamaru-za: Japan's Oldest Kabuki Theatre': "It is not clear from the picture, but there are three entrances (kido) into the theatre, left, center, and right, under the eaves. Those to the left (the okido, "large entrance") and right (goyo kido, "honorable use entrance") are of normal height, but the entrance in the center is very low, forcing theatregoers to bend over in order to enter... This is the nezumi kido ("mouse entrance"), so named because of its supposed resemblance to a mouse hole. It was standard in all Edo-period theatres as an effective means of crowd control: since only one person at a time could enter, it was difficult to get in without a ticket. I did not avoid banging my head upon entering. In the nineteenth century, my head might also have been bashed-had I started a fight or tried to gate-crash-by a stick-bearing guard hired to keep order."

The Kanamura-za is not located in a major metropolitan area. Theaters in large cities often had adjoining teahouses (shibai jaya) through which patrons could enter. |

|

Nichiren |

日蓮

にちれん |

Buddhist priest (1222-82) who was an evangelist of the Hokke or Lotus sect.

"...though based upon the canonical scriptures [the Lotus sect] was of truly Japanese origin. It was founded by a Japanese teacher and it was hostile to all other forms of Buddhism. It was militant and intolerant, and therefore exceptional in a country where the common religious tradition was tolerant to the point of indifference." Nichiren "...held that the truth was to be found only in the Lotus Sutra, and called upon believers to strengthen their faith by repeated utterance of the formula 'Namu-myōhō-renge-kyō,' meaning Homage to the Wonderful Law of the Lotus Sutra."

Nichiren preached an apocalyptic doctrine and he claimed that his coming as a bodhisattva was foretold. He was also fervently patriotic. "...though he preached and wrote energetically about peace, he was a most quarrelsome and intractable saint...who used violent language to condemn the leaders of other sects..." calling them liars, fiends and devils. However, his invectives were not limited just to his religious rivals. He also attacked the governing classes. Tried for treason he was due for execution when he was spared at the last moment. Nichiren described this as a miracle. Over the ages many other miracles have been attributed to him. Convinced of his messianic role he never relented that all of Japan should follow him. Nevertheless, by 1282 when he died everyone had not come on board.

"Nichiren is the most remarkable figure in his country's religious history, and he is certainly among the first dozen of her great men." (Source and quotes: A History of Japan to 1334, by George Sansom, Stanford University Press, 1993, pp. 426-8)

Sansom also believes the roots of Japanese nationalism begin with Nichiren and not centuries later.

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Kuniyoshi showing Nichiren performing a miracle during a storm at sea. This was sent to us by our generous contributor E. Thanks E! 1 |

|

"In 1222, a child was born, who was named Nichiren, because his mother dreamed that the sun (nichi, in Japanese) had entered her." (Quoted from: Story of the World's Worship; : A Complete, Graphic and Comparative History of the Many Strange Beliefs, Superstitious Practices, Domestic Peculiarities, Sacred Writings, Systems of Philosophy, Legends and Traditions, Customs and Habits of Mankind Throughout the World. Ancient and Modern by Frank S. Dobbins, 1901, p. 658) |

||

|

|

||

|

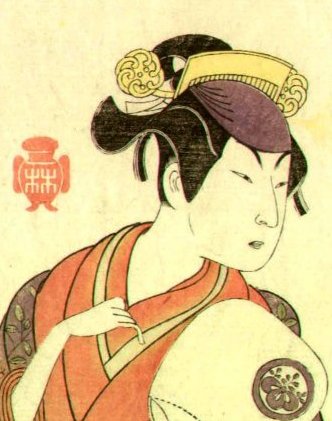

Nigao-e |

似顔絵

にがおえ

|

A true likeness in portraiture: Prior to the late 18th century most print portraits had a generic look to them. Only an identifying crest or accompanying text enabled the viewer to discern which actor he was looking at. Donald Jenkins noted that in print form prior to that "...the faces of actors were indistinguishable from one another and all but interchangeable." Then Bunchō and Shunshō began to draw the face with individualized characteristics such as a hooked nose, narrow chin or high cheekbones. Suddenly it was clear to anyone who knew the theater well which actor was portrayed. (Quote from: The Actor's Image: Print Makers of the Katsukawa School, Timothy Clark, Osamu Ueda and Donald Jenkins, Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 16)

Jack Hillier in his The Art of the Japanese Book (vol. 1, pp. 330-35) stresses that the publication of the Ehon Butai Ōgi (絵本舞台扇) 'The Picture-book of Stage Fans' in 1770 was one of the greatest collaborations ever between two artists "...when...Shunshō and Bunchō brought [an] amalgam of dramatic portraiture and Harunobu-esque colour and grace to a peak..." Bunchō, Hillier notes, suppressed his individualistic artistic instincts to work cohesively with Shunshō. Each actor image was displayed within a fan or ogi motif. Only the two different artists' seals make the attributions iron clad. Shunshō (bottom left) used his Hayashi seal and Bunchō (top left) used a seal featuring his family name, Mori.

We want to thank our correspondent E. for providing these images and helping us graphically to make our point. Images are almost always better than words - or, at least, better with words. Thanks E!

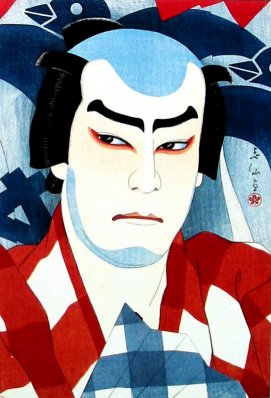

Between 1925 and 1929 one of my favorite 20th century Japanese print artists, Natori Shunsen, produced a series of 36 actor prints in which the term nigao-e plays a major part. They were published by Watanabe Shozaburō. The title of the series was Shunsen nigao-e shū (春仙似顔集) or "A Collection of 36 Portraits by Shunsen". Below is just one example from this series is this portrait of Jitsukawa Enjaku II ([二代目]実川延若) as Danschichi Kurobei (団七力郎兵衛).

In 1817 Toyokuni I produced his manual for "The Quick Instruction in the Drawing of Actor Likenesses" or Yakusha nigao hayageiko. There is a copy of this in the collection of the British Museum and it is a page is illustrated in Chushingura and the Floating World: The Representation of Kanadehon Chushingura in Ukiyo-e Prints by David Bell (2001, p. 111).

Early in his career - ca. 1794 - Utamaro also used the term nigao in the title to one of his series of prints of beautiful women. This may have been influenced by the appearance of those remarkable prints being produced at that time by Sharaku. |

|

"Toyokuni's depiction of highly stylized facial features in a conventional three—quarters view of the head follows pictorial precedents established in nigao, or 'true likenesses'... Nigao offered a system of standardized, highly stylized caricature—like 'distillations' of likenesses of individual actors. Introduced by Katsukawa Shuncho from the 1760s the convention was widely employed well into the nineteenth century." Quoted from: Chushingura and the Floating World: The Representation of Kanadehon Chushingura in Ukiyo-e Prints by David Bell, 2013, p. 32. |

||

|

|

||

|

Nigimitama |

和魂 にぎみたま |

"The nigi-mitama, which is the counterpart of the ara-mitama, is described as mild, quiet, refined, peace, what gives peace, what makes adjustments to maintain harmony, a spirit empowered to lead to union and harmony..." Quoted from: Shinto: At the Fountainhead of Japan by Jean Herbert, p. 44. |

|

"At the shrine, usually nigimitama is enshrined in the main- or inner-shrine called honden..." The nigimitama is also installed in the ihai, the mortuary or memorial tablet. Source: The Essence of Shinto: Japan's Spiritual Heart by Motohisa Yamakage, p. 134.

"It is understood that the idea of one spirit, four souls is inherent in all things. With minerals, aramitama is the predominant influence, whilst with plant and animal life nigimitama is foremost." For example, in trees nigimitama represents the sap and resin. In humans it "Governs the blood, body fluid, lymphatic fluid, skin, hair, brain, eyeballs, etc." (Ibid., pp. 134-135)

In footnote 164 of Motoori Norinaga's The Two Shrines of Ise: An Essay of Split Bamboo (p. 55) it says: "It is believed that one god can have several spirits, each of a different character. A god's mild, luck-bringing aspects are worshipped as his 'Gentle Spirit' (nigimitama), and his forceful, destructive aspects as his 'Turbulent Spirit' (aramitama)."

According to Shinto: A Celebration of Life by Aidan Rankin (p.32) a balance between aramitama and nigimitama means that things will work smoothly, as they should. An imbalance can cause spititual and physical illnesses. "Their sundering can result in death, which is departure of the animating principle, or essence, from the physical being." |

||

|

|

||

|

Nihachi |

二八 にはち |

Soba udon mixture 1 |

|

Nihon zutsumi |

日本堤 にほんづつみ |

The Nihon zutsumi was a dike or embankment which led to the New Yoshiwara from the direction of Asakusa (浅草). |

|

According to J. E. De Becker in his Yoshiwara: The Nightless City (pp. 15-16) it may have been constructed as early as 1621 and originally was made up of two roadways. In time one of them disappeared to public work projects. The remaining dike/road ran 5004' long and 60' wide with a horse path taking up half of that. "At the time of the construction of the Nihon-dsutsumi, a large number of lacquer-trees (urushi-no-ki) were planted on both sides of the road, forming a veritable avenue,* and it was a common joke to warn an habitué of the Yoshiwara by saying significantly - 'When you pass along the Sanya road, mind you don't get poisoned by lacquer!'"

De Becker added the asterisk: "Trees planted in this manner by the authorities were called 'goyō-boku,' or 'government trees.' Lacquer trees are poisonous, and the sap produces a severe rash on the skin if handled."

But that wasn't the only hazard of traveling atop this dike. According to Cecilia Segawa Seigle in her Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan (pp. 57 and 114-5) individuals and groups were made more vulnerable to assaults and robberies. This was especially true of men who were leaving the Yoshiwara after a night of debauchery. She also relates one early account which she says some scholars consider vulgar. I am not a scholar, but I would tend to agree with that assessment so I am not going to repeat it here. However, if you would like to read it for yourself you can find it on pp. 44-45 of Seigle's book.

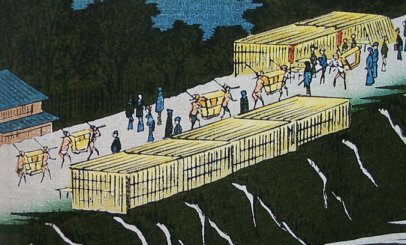

The image shown above is a detail from a print by Hiroshige ca. 1858. Noticeable is the lack of lacquer trees lining both sides of the route. Curious, hmmm? Maybe they were removed for safety reasons. Who knows?

De Becker noted that the original name for the road was written differently as 二本 which can be translated as 'two lines'. |

||

|

|

||

|

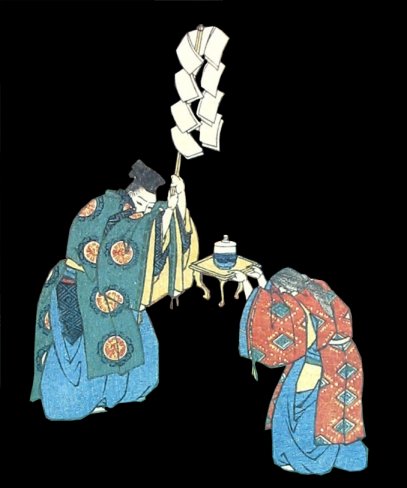

Nijūshikō |

二十四行孝

にじゅうしこう |

24 Paragons of Filial Piety: As early as the beginning of the eleventh century it was common practice among the highest members of the imperial court to perform a fumihajime or ritual reading of part of the Confucian, Chinese based, nijūshikō by a son of seven or eight. "Ostensibly to show the child how to read, it was a purely symbolic event, during which the elaborately robed young principal sat in silence while a Reader (Jidoku) intoned, and a Repeater (Shōfuku) repeated, a few words from a suitable text, usually the Classic of Filial Piety (Hsiao-Ching). At Crown Prince Atsuhira's fumijajime, held on the Twenty-eighth of the Eleventh Month, 1014, in Tsuchimikado Mansion, only the title and the first four characters of the Hsiao-Ching were read. As was usual the assembled dignitaries then adjourned to another part of the mansion for a banquet." (Quoted from: Footnote 1, Chapter 12 (Clustered Chrysantemums), A Tale of Flowering Fortunes:Annals of Japanese Aristocratic Life in the Heian Period, translated by William H. McCullough and Helen Craig McCullough, Stanford University Press, 1980, vol. 2, 1980, p. 429)

Both of the illustrations here of filial piety are from prints by Kuniyoshi. The irony is that the "24 Paragons of Filial Piety" were assimilated from the immutable Chinese concepts handed down by Confucius while the images are most definitely adaptations of Western art.

|

|

An indication of the consistency of tradition in the Imperial Court comes from Donald Keene's Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852-1912 (Columbia University Press, 2002, p. 3). Keene quotes from the memories of Higashikuze Michitomi, a childhood friend of the future Meiji Emperor. "On the seventh day of the sixth month, his ninth birthday, there was the ceremony of 'first reading.' It was not that the prince had never read anything before he was nine. He had in fact already read the Classic of Filial Piety and the Great Learning... and the ceremony was purely a formality. The prince sat in the middle level wearing an ordinary court costume, his sleeves held back by threefold purple cords and laced trousers with violet hexagonal patterns." A low desk is placed before the prince and one of the court figures "...of the third rank came forward and seated himself before the desk. He read the preface to the old text of the Classic of Filial Piety three times. The prince immediately read through this text in the same way." The desk was then taken away and the prince withdrew.

In her translation to another Japanese classic, the "Tales of Ise", Helen Craig McCullough wrote about the influence of Confucianism on Heian society (平安時代 - 794-1195): "Heian society was hedonistic, but not debauched, extravagant but not unrestrained. Excess of any kind was vulgar, vulgarity was the unpardonable sin. Confucian influence thus helps to account for the restraint, refinement and elegance of Heian court life and Heian court poetry - and also, it must be added, for the tyranny of tradition, the concern of form at the expense of content, and the bloodless quality of the typical Heian courtier as he appears in literature, all graceful poses, fine robes and fashionable airs." (Tales of Ise: lyrical episodes from tenth-century Japan, Stanford University Press, 1968, p. 22.)

In the 8th century there was an empress who "...issued an edict that each household in Japan should provide itself with a copy of Hsiao Ching, the Confucian 'Classic of Filial Piety'..." (Quoted from: The World of the Shining Prince: Court Life in Ancient Japan, by Ivan Morris, Kodansha International, 1994, p. 95)

Morris continues: "It is hard to say how much this stress on the family unit derived from Confucian influence and how much from early native tradition. The circulation of books like the 'Classic of Filial Piety' must have helped to give concrete, systematic form to ideas until then were somewhat amorphous and ill-defined. The stress on family continuity, and the widespread habit of adoption that it involved, were certainly related to Confucian doctrine, which regarded the absence of posterity as the greatest of crimes. Ancestor worship and its numerous ramifications were mainly of Chinese origin; there is nothing in the native religion that prescribed the worship of deified men by their descendants." (Ibid., 95-6) ¶ Morris notes that even early on by the time of Murasaki Shikibu adherence to Confucian concepts was more window dressing than sincere practice: "...we often get the impression that the precepts laid down by Confucius and his followers did not weigh too heavily on them when it came to their actual behaviour. Prince Genji, for instance, may have paid lip service to the theories of the family cult and filial piety, but from a Confucian point of view his life could hardly been less exemplary. Yet Murasaki presents him almost as an ideal hero and no doubt most of her contemporary readers accepted him as such. It was not until centuries later that Genji, Fujitsubo, and other characters in the novel were condemned for their flagrant breaches of Confucian ethics." (Ibid., p. 96)

The Daigaku-ryō (大学寮) or 'University Bureau' was established in the 7th century to train mostly the sons of higher rank court officials for the posts of state administrators. Based on contemporary Chinese models they studied among other things - you guessed it - the Confucian 'Classic of Filial Piety'.

"The Classic of Filial Piety and the Analects served as primers for Chinese sociopolitical concepts. If the Analects provided the locus classicus for the polestar monarch... the Classic of Filial Piety homologized the relationship between fathers and sons with that between rulers and subjects to extend the duties of filial piety beyond the household..." (Quote from: The Emergence of Japanese Kingship, by Joan R. Piggott, Stanford University Press, 1997, p. 172) |

||

|

|

||

|

Nikkō |

日光

にっこう |

Nikko has been a center for mountain worship since ancient times, and has always been feared as the home of gods and supernatural beings. Its history began in 766, when the priest Shōdō Shōnin climbed the mountains of Nikko and built Shihonryū-ji Temple to the gods of the mountains. Since that time, Tōshōgu Shrine, Futarasan Shrine, Rinnō-ji Temple and 54 other shrines and temples have been built here, making hte area one of Japan's most important religious centers. It is also an unparalleled sightseeing area, with its shrine and temple buildings, displaying the peak of Japanese art and crafts, blending harmoniously with the beautiful and mysterious natural scenery." Quoted from: Illustrated Must-see in Nikko, p. 14.

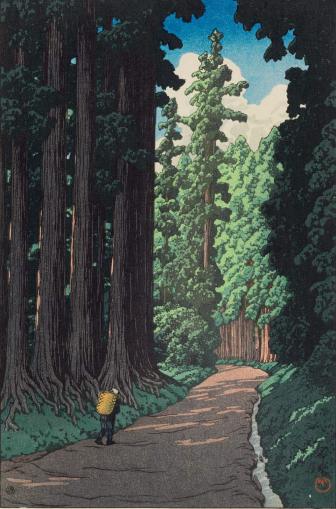

The Hasui print to the left is entitled "The Road to Nikko". It dates from 1930. The photo shown above was posted at Flickr by Albert. |

|

Nimaitsuzuki |

二枚続

にまいつづき |

A Japanese woodblock diptych or two-panel composition. (See also ichmai-e and sanmaitsuzuki.)

|

|

Ninja |

忍者

にんじゃ |

Timothy Clark translates this phrase as "shadow warrior". 9 Quote from: The Actor's Image: Print Makers of the Katsukawa School, Timothy Clark, Osamu Ueda and Donald Jenkins, Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 112)

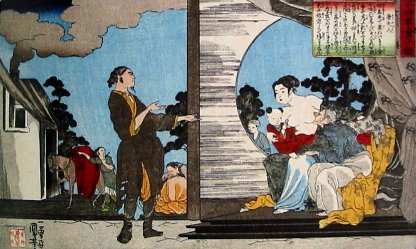

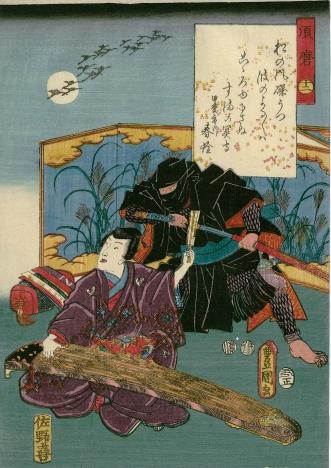

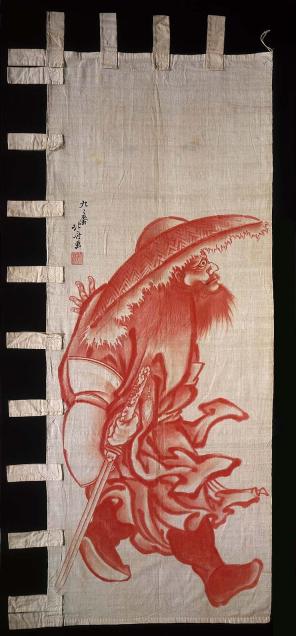

Below is an 1883 Toyonobu of a ninja sent to assassinate Nobunaga. He must be the one standing in the entryway.

|

|

Practitioners of the ancient art of subterfuge. "...a supposedly magical art for making oneself 'invisible' by artifice or strategem in order to evade detection, used especially by those engaged in espionage. Also known as shinobi [忍び]." The author of the entry in the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan refers to ninja as "secret agents".

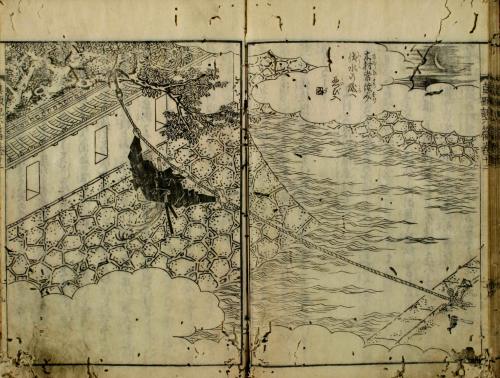

Above is a scene from the

Ehon Taikoki

There are numerous theories about the origin of the ninja, but as Tomiki Kenji says they "...are nothing more than legend." One school believes that Susanoo no Mikoto, the brother of the sun goddess, started it off by turning his new bride into a comb which he stuck in his hair. In another version a different god or kami ordered a pheasant to spy for him. By the time of the Sengoku period (1467-1568) the practices of the ninja were in full swing. These spies were similar to what we now know in the West as the CIA and MI-5 where often agents work surreptitiously behind enemy lines. But like the modern espionage institutions much of what we think we know about them is clouded in nearly complete secrecy and almost totally unreliable. (Source material from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan entry by Tomiki Kenji Suzuki, vol. 6, pp. 6 & 7) |

||

|

|

||

|

Ningyo |

人魚

にんぎょ

|

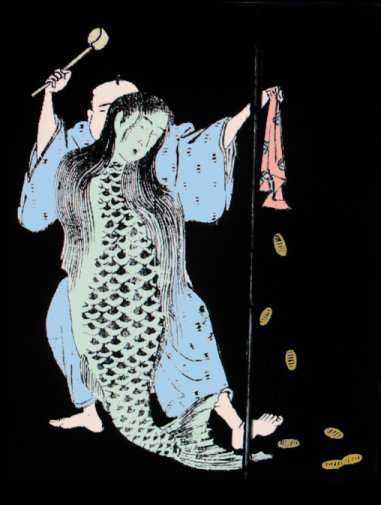

Mermaid (or merman): There is almost nothing I can find about Japanese mermaids in English in my reasonably large, reference library. This is quite odd. In fact, there are almost no mermaids portrayed in Japanese prints. I know of only a couple of example. However, there is an ehon illustrated by Toyokuni I with numerous images. But what the exact story is I don't know. (The image to the left is a detail of one of Toyokuni's early 19th century illustrations. The coloring is mine. Sacrilege. Note also the gold coins which the fellow is dropping at her tail.)

There is the tale of Yaohime (八百姫) or the 800 year old virgin: In one version it is the 5th century. Several men are invited to a feast by a very strange man. However, none of them will eat any of the equally strange looking food. As the guests are leaving one of them grabs a piece of meat, takes it home, wraps it in paper and puts it on a shelf at home. His young daughter finds it and tastes it. As a result she becomes strikingly beautiful and never grows older than fifteen. After 800 years she dies and a shrine is erected to honor her. ¶ "There are many ancient records of ningyo or mermaids appearing in the sea around Japan." Most sketched 'from life' are said to be strikingly beautiful. Sometimes they are shown with arms and breasts and sometimes their whole body is that of the fish with only the head that of a human as in the example to the left. (Source and quotes: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 233)

The description of mermaids given above allow for only two types: Those with breasts and those without because everything below the neck is supposedly fish. However, there appears to be a third category: The breasts are actually fins. Now there is the rub. Whenever you read something about Japanese culture or more specifically about Japanese prints and the author sounds definitive and absolute, don't believe it. If there is anything about Japanese prints which could be considered doctrinaire then let me know what it is. The image shown below is one such case in point. Look at her chest. Look at it carefully. (To be fair, it may just be the invention of this artists, but considering the fact that mermaids are not facts then it would seem the variations are almost endless and any artist can say 'She looked like this. Really. Exactly like this.' And, who is to prove otherwise.)

|

|

Niō |

仁王

におう

|

The two benevolent guardian kings found at the entry to Buddhist temples.

"Niō...the two Deva kings; a pair of guardian divinities of a temple. Statues of them stand at the sides of a temple gate or a Buddhist image. Their task is to guard the temple or the Buddhist image from evil spirits with their fierce countenances. They are also referred to as Kongō-Rikishi [金剛力士]: one is Kongō with his mouth open as if saying 'a' (あ) which implies 'beginning,' and the other, Rikishi, has his mouth closed as if saying 'n' (ん) which implies 'end,' these implications having to do with Buddhist doctrines."

Quote from: Dictionary of Japanese Culture by Setsuko Kojima and Gene A. Crane, p. 243.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary a Deva is "A god, a divinity, one of the good spirits of Hindu mythology."

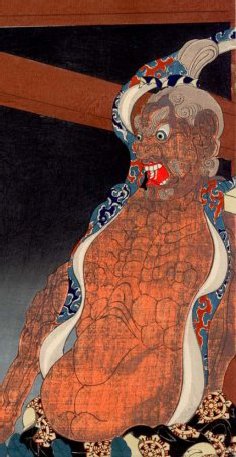

The images to the left both emphasize the 'human' nature of these figures. Although they would have been carved of wood they were meant to instill a sense of unearthly power in believers. The one on the top is a detail from a print by Kuniyoshi where he honors the remarkable sculptor Hidari Jingorō (左 甚五郎 - fl. late 16th to early 17th c.) who like Pygmalion was so adept at his craft that one could easily believe that his creations could come to life. In this case Kuniyoshi has used a kabuki actor's visage for his model. The one below is a detail from a vertical diptych by Kuniyoshi's pupil Yoshitoshi. That image was sent to us by our dear friend Mike. Thanks Mike! |

|

Nise Murasaki inaka Genji |

偐紫田舎源氏

にせむらさきいなかげんじ

|

"An imposter Murasaki and rustic Genji" was a serial novel written by Ryūtei Tanehiko (1783-1842: 柳亭種彦) and published by Tsuruya Kiemon (鶴屋喜右衛門) between 1829 and 1842. It was probably the most popular novel written in the 19th century and made even more so by the wonderful illustrations of Kunisada. In fact, Kyokutei Bakin (1767-1848: きょくてい.ばきん), a rival author and rather snippy competitor, "...ever acerbic, declared the illustrations the single best feature of the entire work." Bakin questioned in particular Tanehiko's lack of scholarship and it is known that after the latter died and an inventory was made of his rather extensive library there were no copies of "The Tale of Genji" by Murasaki Shikibu. But in the end this does not mean very much.

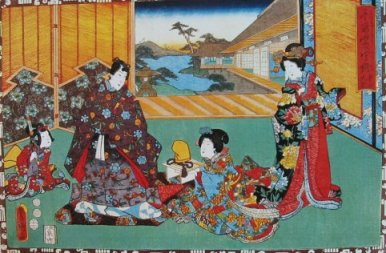

(The illustrations to the left and below are both by Kunisada. The top one is a detail sent to us by one of our valued correspondents. For this we thank him heartily. Remember these are only two examples of an enormous corpus of such prints which form their own genre.)

|

|

This new, nineteenth century variation on the theme of Genji had numerous intervening precedents going back several centuries. Even the great author of puppet plays, Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1724: 近松門左衛門) composed works which have been described as "freewheeling adaptations of Genji..."

The early chapters of the Rustic Genji hardly show a knowledge of the original 11th century masterpiece. Prince Genji was renamed Matsuuji (光氏) who was made the son of a shogun rather than that of an emporor. Even the styles were divergent. Compared to the elegant (ga: 雅) "Tale of Genji" this new version was considered vulgar (zoku: 俗). There was more of kabuki in the early part of this series than anything else. Tanehiko knew his market well and catered to its needs: dramatic struggles, the search for stolen treasures, twists which made sudden turns, love trysts in the pleasure quarters. All of this occured in a condensed fashion.

Bakin insisted that this novel was geared more to women and children than to educated men. There may be a grain of truth in this considering that most of Tanehiko's contemporaries were ignorant of Lady Murasaki's work. Her writing was too plodding and archaic for most of the population. Tanehiko spiced it up and the public loved it.

Originally Genji was set in the Heian period (794-1185: 平安). However, Mitsuuji's is a Muromachi (ca. 1336-1573: 室町) blade. But this is a Muromachi period unlike any other. Tanehiko modernized it with a slew of oddities. "He notes, even underlines in chapter prefaces, the deliberate anachronisms he has introduced: clocks, telescopes, tobacco, a sort of Greek fire borrowed from 'Southern barbarians,' and the shamisen, 'newly introduced from the Ryūkyūs."

In later chapters - Tanehiko died before finishing the novel - he moved much closer to the original "Tale of Genji". "...the author is at pains to provide some equivalent for even slow moving portions of the relatively static 'Suma' and 'Akashi' chapters." However, by the end of his efforts Tanehiko "...adhere[s] most conspicuously to the episode sequence of the original, even to the point of mechanical parallel transposition of consecutive Genji chapters into consecutive Inaka Genji half-chapters." Sometimes the Heian work is quoted "...verbatim or with minor modifications. While the tense theatrical style of the earliest chapters does surface sporadically, these final, most imitative segments represent the final victory of the 'elegant' component, and capitulation of the 'vulgar'." (Source and quotes from: The Willow in Autumn: Ryūtei Tanehiko, 1783-1842, by Andrew Lawrence Markus, Harvard University Press, 1992, pp. 119-158)

THE POINT: There are a load of Genji pictures out there - many if not most of them by Kunisada, aka, Toyokuni III - and they remain extremely popular among today's collecting public. Often these prints have those nearly ubiquitous Genji-mon or little crests which ostensibly represent identifiable chapters. But beware! They don't always line up with the texts - at least as best I can tell. And, goodness knows, they often have no clear connection with anything written from the brush of Lady Murasaki.

MORAL: Don't try to figure out the iconography of the Genji prints you own or see unless you are used to pulling your hair out. If and when there is a good/great English translation the Rustic Genji then we can revisit this problem.

******

"The love affairs that sprinkle the pages are described with conventional skill and heightened by the charm of Kunisada's illustrations, but there is something unpleasantly cold and deliberate about Mitsuuji's systematic use of the women he sleeps with to further his investigation. Judged in terms of the samurai morality, Mitsuuji is superior to Genji in that his love affairs are occasioned not by fleshly lust but by a higher purpose, recovery of the treasures. But it is hard for us to feel affection for this love machine or, for that matter, for the women of different social stations who vie to become his slaves." (Quoted from: World Within Walls: Japanese Literature of the Pre-modern Era, 1600-1867, by Donald Keene, Holt, Rhinehart and Winston, 1976, p. 433) ¶ Donald Keene makes it clear that Tanehiko was well aware of his model. "Tanehiko also had difficulties determining how faithful he should be to the plot of The Tale of Genji. His manuscripts are full of crossings out and additions, indicating his uncertainties, especially at the beginning of the work. It was with great reluctance that he finally dropped an opening paragraph directly modeled on Lady Murasaki's famous lines, but as a mark of tribute to the original author he pretended that a woman, a court lady named Ofuji, had written his work." (Ibid., p. 432) |

||

|

|

||

|

Nishiki-e |

錦絵 にしきえ |

Literally 'brocade print'. |

|

This is the term for style of colored woodblock prints which form the overwhelming majority of ukiyo production where each color requires the use of a separate block. It stands in contradistinction to that of earlier hand-colored prints. While many sources state that Harunobu originated this technique in 1765 there are at least two other examples by Shunshō from the previous year. This is according to Timothy Clark of the British Museum. "Some authorities maintain, however, that Shunshō's earliest nishiki-e actor prints date from 1768; see, for example, Rober Keyes's comments in Ukiyo-e Shūka, vol. 13 (1981), no. 126." (Quote from: The Actor's Image: Print Makers of the Katsukawa School, Timothy Clark, Osamu Ueda and Donald Jenkins, Princeton University Press, 1994, p. 94, note 2.) |

||

|

|

||

|

Niwaka |

俄 にわか |

Sudden, abrupt, unexpected, improvised: This is also the description of a form of 'spontaneous' entertainment held each year in the Yoshiwara or red light district of Edo. In time it was considered one of the three greatest events of the Yoshiwara and was performed in the eighth month. It originated in the early 18th century and became an annual event starting in c. 1732. "This was an entertainment planned in conjunction with the festival of Kurosuke Inari, Yoshiwara's patron fox-god. (Quoted from: Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan, by Cecilia Segawa Seigle, University of Hawaii Press, 1993, p. 108) "By the end of the eighteenth century, niwaka was an elaborate festival with a parade of floats carrying courtesans, shinzō, and kamuro performing to the music of drums, shamisen, and flutes. The procession stopped in front of every other teahouse and the courtesans, shinzō, and kamuro did a dance atop the float. It was a colorful festivity that grew larger and more extravagant with time. The Japanese love of festivals ensured that this event would attract many spectators from Edo, just as the Yoshiwara proprietors had hoped." (Ibid.) Geishas who participated arranged their hair to make them look like young men. (Ibid., p. 129) ¶ There must have been a hiatus in these performances at the Yoshiwara because Allan Hockley in his book on Koryūsai said they were revived in 1776 to help bring attention and business to the district. ¶ Niwaka is described as "...an amateur theatrical entertainment then popular [i.e., the early 18th c.] in the Osaka pleasure quarters that was heavily dependent upon wordplay." (Quoted from: Shikitei Samba and the Comic Tradition in Edo Fiction by Robert Leutner, p. 67) ¶ In a footnote Leutner says "It has often been pointed out Ikku's Hizakurige was strongly influenced by niwaka, another late-Edo comic storytelling art. (Ibid., p. 129) [See our entry on the Shank's Mare on our Seikichiku thru Sh page.]

In The Yoshiwara From Within, an unattributed 19th century account, the author state: "...the professional buffoons, belonging to the infamous quarter, as well as the singing and dancing girls, all in disguise, perform the low comedy, usually men in women's and women in men's dress. Besides, some ten or twenty singing-girls, wearing men's clothes, draw a gigantic lion-head made of wood, unitedly singing barbarous songs, accompanied with strange music. These are old standing customs. At this time they make their garments as beautiful and costly as possible, it being a matter of emulation among them." |

|

Nobori |

幟

のぼり |

A military, samurai banner - "A nobori (幟) is a tall identifying banner attached to a vertical pole and a top horizontal crosspiece. This level of support allowed the banner to remain visible regardless of wind. The banner's association with a particular commanding daimyō led to their frequent use to indentify army subdivisions." Quoted from: O-umajirushi: A 17th-Century Compendium of Samurai Heraldry, p. xvi.

|

|

Noh |

能

のう |

A classical form of Japanese theater. Andrew L. Markus in his article "The Carnival of Edo: Misemono - Spectacles From Contemporary Accounts" published by the Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies says "Though refined into an elite private art form during the late medieval period, the stately nō drama traces its origins to the popular public sarugaku 猿楽 'monkey diversion' show - and in some opinions ultimately to the sangaku 散楽 'miscellaneous entertainment' acrobatics of the Nara period." The illustration to the left comes from a "...hand-coloured tanryoku-bon 1660 book Kyogen-ki by an unknown artist."

This image was generously contributed to our site by E. Thanks E! 1 |

|

Nokori-enogu |

残り-絵の具 のこりえのぐ |

Cherry-wood blocks are desirable for their quality of nokori-enogu or as Hiroshi Yoshida notes "...it has power to retain a part of the pigment after printing. By the time about ten sheets have been printed, the block absorbs and retains some of the pigment which cannot be wiped off or printed away and which gives a desirable tone to the print." ( Japanese Woodblock Printing, 1939, pp. 16-17) |

|

Norimono |

乗り物 のりもの |

Literally it means 'vehicle', but in this case it is the elegant, lacquered, enclosed palanquin used by a daimyo or other high official when traveling.

In The Shogun Age Exhibition (cat. entry #239, p. 232) it states "...one rode facing forward with legs tucked underneath. Although the interior seems small and cramped, there was sufficient room for reading and writing and performing small tasks." Slats on the front and the sides could be adjusted from the inside for better views of the scenery. 1 |

|

Engelbert Kaempfer in his 18th century book on Japan discussed the differences (and similarities) between the common kago and the elegant norimono. [cf. kago on our J thru Kakuregasa index/glossary page] The "handsome and hollow" pole of the norimono "consists of four thin boards skillfully joined to resemble a narrow, solid pole with a rising curve in the center, and it is therefore much lighter than it appears from the outside. The height and length of these poles are regulated by law according to one's station, and the eminence and lofty station of rulers and high-ranking lords are mainly indicated by the height of these carrying-poles. Those who consider themselves to be greater than they actually are occasionally use poles with a curve higher than that permitted, but they often fare badly and with much humiliation are forced to remove it. This government regulation does not apply to women, and they are not prohibited from going beyond their station. The compartment itself is an oblong cubicle, and the largest are so big that a person can sit and rest comfortably. The walls are carefully woven from finely split bamboo, sometimes lacquered, delicate, and precious. On each side is a sliding door, and in it or next to it - sometimes also in the front or at the rear - is a small window. On occasion they also have a small flap at foot level so that people can sleep with their legs stretched out."

Quoted from: Kaempfer's Japan: Tokugawa Culture Observed, edited and translated by Beatrice M. Bodart-Bailey, University of Hawaii Press, 1999, p. 246. |

||

|

|

||

|

|

納札

のうさつ

|

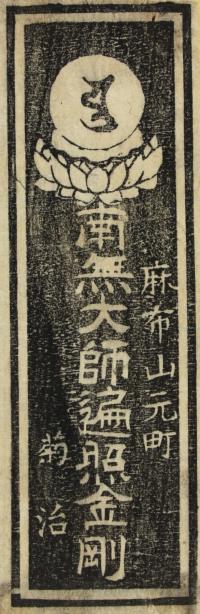

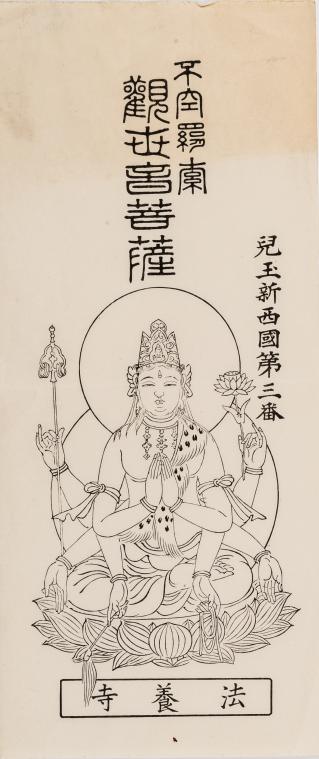

A votive tablet or card donated to a shrine or temple - Mayumi Takanashi Steinmetz, in a master's thesis at the University of Oregon in 1985, wrote: "Nosatsu is both a graphic art object and a religious object. Until very recently, scholars have ignored nosatsu because of its associations with superstition and low-class, uneducated ho.bbyists. Recently, however, a new interest in nosatsu has revived because of its connections to ukiyo-e. Early in its history, nosatsu was regarded as a means of showing devotion toward the bodhisattva Kannon. However, during the Edo period, producing artistic nosatsu was emphasized. more than religious devotion. There was a revival of interest in nosatsu during the Meiji and Taisho periods, and its current popularity suggests a national Japanese nostalgia toward traditional Japan." 納札 can be translated as 'placard for payment'.

Nōsatsu or senjafuda (千社札) devoted to the bodhisattva Kannon from the collection of the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon |

|

|

縫ぐるみ

ぬいぐるみ |

"Literally 'sewed wrapping', a costume of an animal worn by a lower ranked actor in a kabuki play. "Nuigurmi refers to animal costumes, of which the most important is the Kabuki horse. The horse is played by two actors who must skillfully coordinate their leg movements to simulate those of the horse. Famous plays in which horses appear include Ya no Ne (The Arrowhead), the final act of Chushingura, and Sanemori Monogatari (The Tale of Sanemori), which contains a humorous moment when the horse refuses to move on. Another famous Kabuki animal is the wild boar (played by one man) in Act V, "The Musket Shot," from Chushingura." Quoted from: Kabuki: a Pocket Guide by Ronald Cavaye.

These images come from a Toyokuni III triptych in Lyon Collection. |

|

Nuka bukuro |

糠袋

ぬかぶくろ |

"Before the introduction of soap and other modern cosmetics, Japanese women had their own way of beautifying themselves. First, in washing their faces they used nukabukuro or little cotton bags containing rice bran. The bag was moistened and applied to the face and hands, or all over the body when taking a bath.

The moistened bran gives off a whitish juice which is believed to be good for the skin."

Quote from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 7. |

|

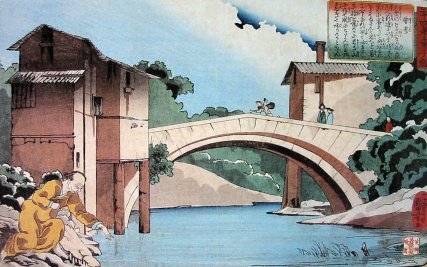

Nunobiki |

布引 ぬのびき |

A term which means stretched cloth or the proper name of a waterfall. 1 |

|

Nunomezuri |

布目摺

ぬのめずり

|

"Textile printing": "...technique of producing textile weave (using no pigment) in finished print..."

Quote from: Japanese Print-Making: A Handbook of Traditional & Modern Techniques, by Toshi Yoshida & Rei Yuki, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1966, p. 168.

In the Yoshitoshi detailed example to the left one can clearly see the textile pattern below the printed text. The image below that shows the full print. The area with the nunomezuri is in the upper left. Such details are very easy to miss. That is why an extremely close reexamination of the prints you already own is well worth the effort. 1

|

|

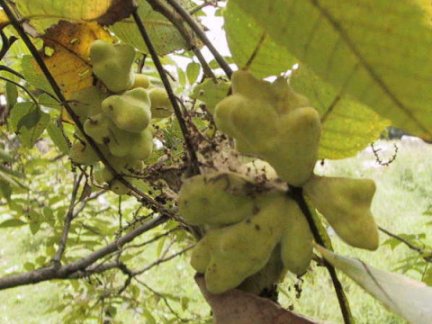

Nurude |

白膠木

ヌルデ |

Japanese sumac rhus javanica. The crushed gall of this plant is used in making of tooth blackening powder applied by married women in the premodern era. (See our entry on ohaguro for a more extensive discussion of tooth blackening.)

These two images, one showing the sumac tree in flower and the other picturing the galls, are being shown courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm. You should make sure to visit Shu's wonderful site. |

|

Nusa |

幤

ぬさ |

A wand composed of a branch of the sakaki tree adorned with a zig-zag cut paper used as a Shinto offering.

(See also the entries for tamagushi, sakaki, shide and shimenawa.)

幤 is also pronounced hei. Also, as nusa it can be an offering of cut paper, cloth or rope.

W. G. Aston in his Shinto: The Way of the Gods describes variations on the nusa or gohei. "The clothing of the ancient Japanese consisted of hemp, yuju (a fibre made of the inner bark of the paper mulberry), and silk. All these materials are represented in the Shinto offerings... Silk, however, was at this time still somewhat of a novelty, and, therefore, religion being conservative, it takes a less conspicuous place. But hemp and bark-fibre, with the textiles woven from them, are very common offerings. They were more convenient than perishable articles of food for sending to shrines at a distance from the capital, and as cloth was the currency of the day, it was a convenient substitute for unprocurable or objectionable articles." ¶ Aston describes one type of nusa called the "...oho-nusa (great offering)... [which] consists of two wands placed side by side, from the ends of which depend a quantity of hempen fibre and a number of strips of paper. One of the wands is of cleyerica japonica, or evergreen sacred tree. The other is a bamboo of a particular species."

To the left is an image taken from a print by Hokusai showing a Shinto priest holding a single gohei. The photograph below was taken by nnh and placed in the public domain at http://commons.wikimedia.org/.

|

|

Nushi |

主

ぬし |

A guardian spirit, usually with mystical powers. Nushi has many other meanings, but all seem related in a way: "(1) head (of a household, etc.); leader; master; (2) owner; proprietor; proprietress; (3) subject (of a rumour, etc.); doer (of a deed); (4) guardian spirit (e.g. long-resident beast, usu. with mystical powers); long-time resident (or employee, etc.); (5) husband; (6) (fam)"

The giant carp at Bishamon falls is often referred to as a nushi. See the Sadahide fan print to the left. |

|

Nyoi-hōshi |

如意宝珠 にょいほうじゅ |

The cintāmaṇi stone or wish-fulfilling jewel. See also our entry on hōju. |

|

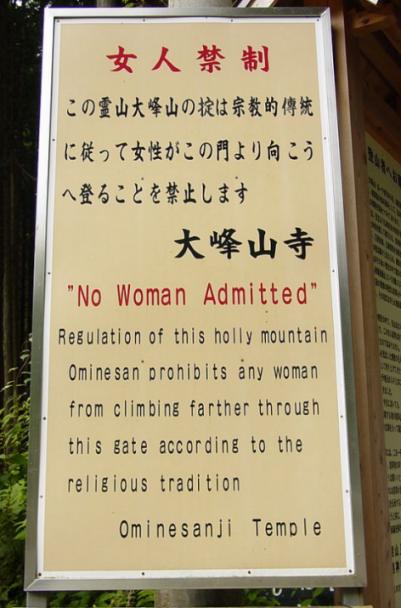

Nyonin kinsei |

女人禁制

にょにんきんせい |

Religious tradition has long dictated the exclusion of women from sacred sites like Sanjōgatake (山上ヶ岳), a sacred peak in the Ōminesan (大峰山) range, southern Nara 奈良Prefecture. "According to tradition, it was founded by En no Ozunu, the founder of Shugendō [修験道], a form of mountain asceticism drawing from Buddhist and Shinto beliefs. ¶ The sanctuary around the Sanjōgatake peak (山上ヶ岳) has long been considered sacred in Shugendō, and women are not allowed in the area beyond four "gates" on the route to the peak. On the neighboring Inamuragatake peak (稲村ヶ岳), altitude 1,726 m, it has been opened as a place of training for female believers since 1959, thus called "Women's Ōmine" (女人大峯 (Nyonin Ōmine)). [This information was found at Revolvy.]

There are stone carved warnings everywhere that read loosely: "Women are restricted from this point on!" (koreyori nyonin kekkai - 從是女人結界). However, in 1872 the Meiji government officially said that all previously off-limit sites should ostensibly be open to women everywhere.

Parsing the individual characters give us 女 (woman) + 人 (person) + 禁 (prohitibion) + 制 (rule).

Also referred to as nyonin kekkai (女人結界).

The photograph to the left was posted at Wikimedia Commons by Tim Notari. |

|

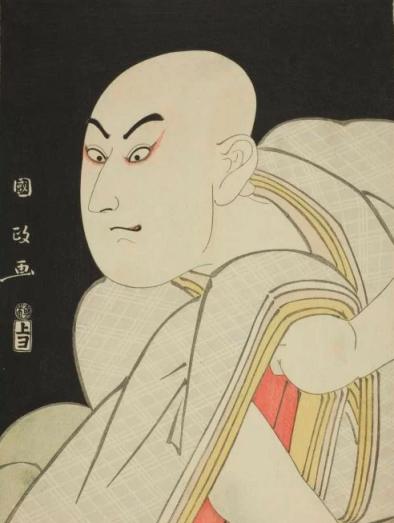

Nyūdō |

入道

にゅうどう |

A lay priest according to the Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary from the 1954 edition. Other dictionaries give more expansive definitions.

To the left is a detail from a late 18th century print by Kunimasa showing the actor Sawamura Sōjūrō III as the lay priest Taira no Kiyomori. |

|

LINKS TO OUR OTHER INDEX/GLOSSARY PAGES Click on any of the pages listed below!

|

||

HOME

HOME