|

|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

|

|

|

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画Kansas City, Missouri |

|

|

|

Index/Glossary

Sekichiku thru Sh |

|

|

|

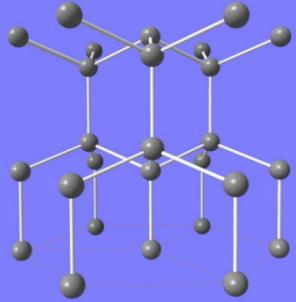

The molecular model on Lonsdaleite is being used as a marker for new additions from January 1 to May 31, 2021. The piece of sulphur posted at Wikimedia by Rob Lavinsky was used from June 1 thru December 31, 2020.

The detail from the diadem of

the Empress Eugénie |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Sekichiku, Sekisho, Semi, Sen, Sendai Hagi, Sengaki,

Senjafuda,

Seno Jūrō Kaneuji, Seppuku, Seriage, Seridashi, Setsubun, Setsuwa bungaku, Settsugekka, Shachi, Shaka, Shakujō, Shamisen, Shank's Mare, Sharebon, Shibaraku, Shichifukujin, Shichigosan, Shide, Shigenobu, Shigoki, Shiitake tabo, Shika, Shikake-e,

Shintai, Shintō, Shinzō, Shiokuni, Shiori, Shippō, Shiraki, Shiranami-mono, Shiratama, Shirizaya-no-tachi, Shishi, Shishimai, Shishi no za, Shishō, Shishu no zōjigoku, Shitadashi Sanbasō,

Shizuki Tadao, Shōbu , Shōchikubai, Shodō,

Shōdō Shōnin,

Shōgi,

Shōhō,

Shōmei, Shōmenzuri, Shōnetsu jigoku, Shonzui, Shōrui Awaremi no Rei, Shosa, Shugendō,

Shugō jigoku,

石竹, 関所, 蝉, 銭, 先代萩, 線書き,

千社札,

瀬尾十郎兼氏, 切腹, 迫上, 迫出, 節分, 説話文学, 雪月花, 鯱, 釈迦, 錫杖, 三味線, 洒落本, 暫, 七福神, 七五三, 紙垂, 重信, 志ご貴,

椎茸髱, 鹿,

仕掛け絵,

七五三縄 or 注連縄, 死絵, 新造, 死に装束, 神体, 新造, 汐汲み, 栞, 七宝, 白木, 白浪物, 白玉, 尻鞘の太刀, 獅子, 獅子舞, 師子座, 四生,

四種の増地獄,

舌出三番叟,

下絵付け, 志筑忠雄, 菖蒲, 松竹梅, 書道,

勝道上人,

娼妓,

正保,

燭台, 正銘, 正面摺, 焦熱也獄, 祥瑞, 生類哀れみの令, 所作,

修験道, 衆合地獄,

襲名,

|

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

||

|

Sekichiku |

石竹

せきちく

|

Pink (or carnation) - the flower and not necessarily the color - motif used as a family crest or mon. The pink is a dianthus. Below is a Sweet William Dwarf (美國石竹) posted at Flickr by beautifulcataya. This example is clearly a hybrid.

There is a haiku by Kyoroku (許六: 1655-1715) quoted in Chado the Way of Tea: A Japanese Tea Master's Almanac by Sasaki Sanmi, p. 357:

石竹や紙燭して見る露の玉

Sekichiku ya

The light from the paper

lantern is reflected

The image to the lower left is the Rainbow Pink (石竹科) posted by Kai Yan and Joseph Wong at Flickr. |

||

|

Sekisho |

関所

せきしょ |

Barrier/checking station: "Government installations at strategic points along traffic routes, where travelers were stopped for inspection from ancient times through the early modern period. The system of barrier stations was established under the Taika Reform of 645, with primary emphasis on those in the Kinai region, or home provinces." Originally there were three major barriers overseen directly by the government: Suzuka in Ise Province; Fuwa in Mino; and Arachi in Echizen. These could be controlled in case the emperor abdicated, died, there was a rebellion or national emergency. In time the three initial barrier stations became less important and private barriers were put up elsewhere and fees were charged for passing through these. "During the Muromachi period (1333-1568) there was a conspicuous proliferation of barrier stations as the shogunate and regional lords sough additional sources of revenue. The sekisho tended to impede the flow of traffic and goods, and they were abolished in the late 16th century by the national unifiers Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi." They were revived in spades during the Tokugawa period and abolished by the Meiji government on March 2, 1869. (Source and quotes from the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 7, p. 57)

To the left is an image of the Hakone sekisho posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Steph Gray. According to Fodor's Tokyo guide book this is one of the most popular tourist sites in Hakone. According to the The Cambridge History of Japan this barrier post was established in 1636. The 2009 Fodor's Tokyo gives the starting date as 1618. Timon Screech relates the story of an artist who reached the Hakone barrier only to realize that he had lost his papers. He tried twice to cross over without permission. This was referred to as sekisho yaburi (関所破り) or 'barrier-breaking', a criminal act. A third attempt was punishable by death. (See: Shogun's Painted Culture: Fear and Creativity in the Japanese States, 1760-1829, pp. 257-8) In Ogyu Sorai's Discourse on Government (Seidan): An Annotated Translation (fn. 546, p. 252) it is noted that at barriers like Hakone all kasa hats and other headgear had to be removed, the doors of norimono (palanquins) had to be opened and riders had to remove one foot from his stirrups. However, this might have been more an ancient sign of respect as opposed to a security issue. |

||

|

The literal translation of sekisho is 関 seki which means 'barrier' or 'gate' and 所 sho which means 'place'.

During the Tokugawa period the sekisho were used to regulate traffic and trade, but also to prevent the smuggling of arms into Edo and the illegal transportation of women as hostages out. The expression used at the time was de onna - iri teppō or "women leaving, guns entering". Travellers were required to carry and show a document of passage called a sekisho-tegata (関所手形). Some sources say these were written on wooden panels.

According to the catalogue of the exhibition Circa 1492: Art in the Age of Exploration it says "Commerce was hampered as well by poor roads and by private toll barriers (sekisho) on the road and rivers, mostly controlled by powerful temples but also by Shinto shrines and perhaps by some shugo." Note: Shugo (守護) were military governors during the Kamakura and Muromachi periods.

In vol. 4 of the The Cambridge History of Japan (p. 114-15) it says that "In the tenth month of 1568, Oda Nobunaga, claiming that he represented public authority (tenka) and that he was acting in the best interests of all people, abolished the toll barriers within his holdings, which at that time officially included just the two provinces of Owari and Mino.... Moreover, he also abolished toll barriers in territories that he occupied later, such as Ise and Echizen, thus advancing a policy of encouraging unrestricted trade. ¶ However, Nobunaga's toll barrier policy did not proceed beyond certain self-imposed limitations. He did not, for example, abolish the imperial checkpoints at the seven entrances to Kyoto." Nobunaga's policies were not totally consistent. Merchants under his protection could ship items toll free while others still had to pay.

From Excursions in Identity: Travel and the Intersection of Place, Gender, and Status in Edo Japan (p. 19): "By allowing transit only between certain hours, checkpoints provided the government with the illusion of controlling not only space but also time. As a general rule, barrier gates were open only between six in the morning and six in the evening. ...exceptions were made to accommodate official travelers, known as the bearers of the 'packhorse red seal' (tenma shuin)."

By the late Edo period many guards would turn a blind-eye to some who would try to skirt the barriers. One village officer from Echigo province noted in his diary in 1774: "There is a checkpoint here and women are not allowed through the barrier. So they circumvent it by taking a boat at Aisaki beach. It costs thirty mon." At other times guards could be bribed. Ibid., pp. 90-1

Daimyō were not permitted to set up sekisho on major roads during the Tokugawa period, but they were permitted to set up barriers on lesser roads within their domains. This they called bansho (番所). Bansho translates as guard house. "The forces maintained at sekisho were modest, ranging from a handful to several dozen guards..." There were physical examinations to make sure that women were not disguising themselves as men, "...or young boys dressed as girls, were trying to slip through." Source and quotes: The Making of Modern Japan by Marius Jansen, pp. 139-140.

As if travel wasn't difficult enough in the late 18th century, marriages between individual on either side of a sekisho was made nearly impossible to bear since even the bride/wife would have to apply for permission to travel back to her parent's home for each and every visit. This put a damper on marriages of couples who lived on either side of the barrier. (This information comes from: Breaking Barriers: Travel and the State in Early Modern Japan by Constatin Vasporis, p, 154.) |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Semi |

蝉

せみ |

Cicada - There is a Bashō peom which contrasts polar opposites:

stillness -- seeping into the rocks cicada's screech

In a comment on this haiku Moran wrote: "A poem by Tu Fu says, 'Cicadas' voices merge together in an old temple.' Bashō further enhanced the poetic beauty of the scene by introducing the image of rocks absorbing the voices."

Another, Sanga, wrote: "This poem's meanings goes beyond its words and points toward the profound secrets of Zen."

In Traditional Japanese Theater: An Anthology of Plays, edited by Karen Brazell, is the script of The Cicada (Semi): a parody of a noh ghost play, translated by Carolyn Haynes. In the preface it says: "A small group of kyōgen plays... are direct parodies of noh ghost plays. In noh, it is usually the ghost of a well-known warrior or a talented or beautiful woman who comes to life on stage, whereas in kyōgen the human ghosts are more lowly: an unskilled umbrella maker (Yūzen), a pushy flutist (Rakuami), and an overworked teahouse proprietor (Tsūen). Another group of kyōgen ghosts are innocent victims of thoughtless slaughter: a field potato (Tokoro) and an octopus (Tako), as well as the cicada of this play." |

||

|

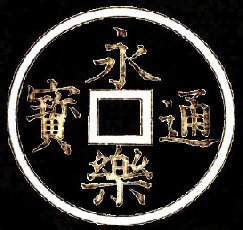

Sen |

銭

せん |

This motif represents the sen which is one hundredth of a yen. "In a society said to despise both merchants and money, the appearance of coins as a heraldic motif may seem surprising." Originally the Japanese did not mint their own coins, but imported them from China. This formed a major part of their trade.

Coins were also important in the Buddhist death rituals. Six coins were placed by the body of the deceased to help the soul on its journey to the nether world. This would act as alms paid to six gods of the afterlife.

Source and quote from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 108.

Mock Joya gives a slightly different explanation for the use of the funereal coins: "...copper coins, or pieces of paper on which the outlines of coins were roughly painted, were placed in the coffin. The ancients believed that Sanzu-no-kawa (Sanzu River) divided this world from Gokuraku (Paradise), and so coins were required to pay for the ferry ride across the river. Since they also believed it was a lengthy journey to Gokuraku straw sandals and a strong staff to lean on were placed in the coffin to aid the traveler."

Quoted from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese (p. 317) |

||

|

Sendai Hagi |

先代萩 せんだいはぎ |

Alternate name for the kabuki play "Date Kurabe Okuni Kabuki" 1 |

||

|

Sengaki |

線書き せんがき |

An outline drawing used to cut the key block. A hanshita is a traced drawing used for the same purpose. |

||

|

First the artist does a loose, conceptual drawing of what will be the final product. If it is figurative more emphasis is generally put on facial features than the rest of the drawing. From this initial step - see our entry on genga - a much more precise outline drawing is prepared. Hiroshi Yoshida in discussing his technique mentions that he uses minogami which has been sized with dōsa. "It is important that the lines should be clear and definite. Ink is to be avoided, for it blurs when the paper is pasted face down on the block to be cut. When taking a pen, sumi should be used." ( Japanese Woodblock Printing, 1939, p. 15) Of course, Yoshida is describing a 20th century method using 20th century tools. He even suggests that one not rush the process. "One should hang it on the wall for a number of days and contemplate it, thinking about the later processes which must eventually follow. If one is too hasty, and it is found necessary to alter or add something afterward, it will be extremely difficult to make the change. It is very essential that one should give all the thought possible just here, before pasting the sen-gaki on the block for cutting." (Ibid.) The artist should be able to extrapolate from this lined piece to the finished product - even the colors which will be used. ¶ Yoshida addressed certain technical problems which could arise. For example, "If two or more colours meet, an extension of one of the lines which is not to remain in the print afterward is generally necessary in the outline drawing for guidance to secure the exact fitting together of the different colours to be applied. Suppose there are to be some glowing clouds in the sunset sky, and a part of them is hidden behind a mountain. When a separate block is made for the clouds and another for the mountain, it is difficult to know afterward the exact position of the clouds in relation to the mountain and just where the line of the cloud touches the slope of the mountain. So the line of the cloud must be extended to cross the line of the mountain slope, thus indicating the exact location which the artist wished to give the clouds. In this case the unnecessary part of the line known as muda-bori [無駄彫 or むだぼり], or "unnecessary cutting," which was extended into the mountain should be taken away after the trial printing is made, and the exact position fixed by the register marks." (p. 16) |

||||

|

|

||||

|

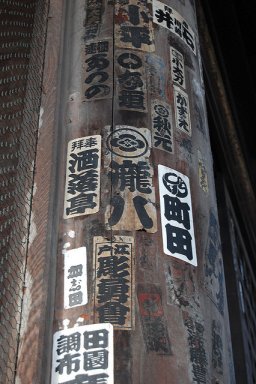

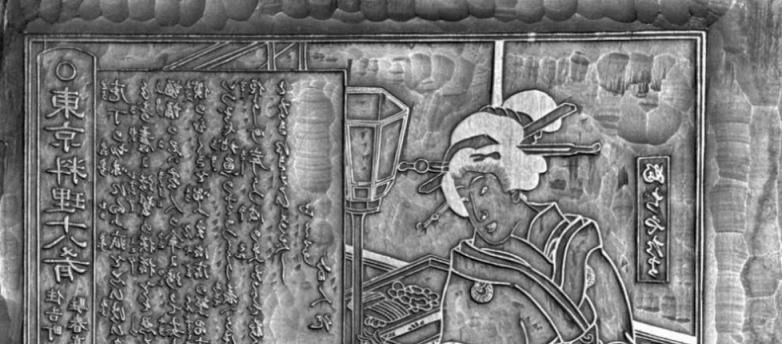

Senjafuda |

千社札

せんじゃふだ |

Small prints posted on shrine pillars by pilgrims. Literally "thousand shrine slip". These are said to be remnants of ancient beliefs in the the power of words combined with pilgrimages. Rebecca Salter in her Japanese Popular Prints: From Votive Slips to Playing Cards (p. 94) tells us that "Chinese pilgrims carried a protective seal which they impressed in the soil of the road to ward off evil spirits as they went. In Japan, it was recommended to write the kanji for 'tiger' on the palm of the hand to terrify wild animals and evil spirits. When crossing a river, the traveller was advised to carry something bearing the kanji for 'earth/ground' to ensure safe passage to the other bank. Senjafuda... are an extension of the belief in the power of the word..." Today individuals commission printed slips with their names and then travel en masse with others to plaster their prints on the buildings "...at each holy site." (Ibid.) ¶ "The classic senjafuda for pasting was and still is a woodblock, printed in sumi ink on a slip of paper about..." 5" high by 2" wide. (Ibid., p. 96)

The photo to the left was posted at Flickr by Jpellgen. It shows the senjafuda attached to one of the entryway pillars to the Zenko-ji. |

||

|

|

線香花火

せんこうはなび

|

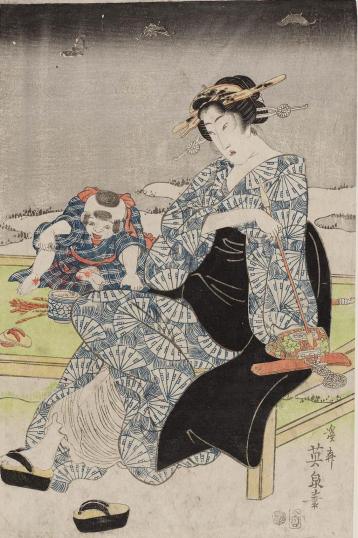

Sparkler(s): We were researching an Eisen shunga print when we stumbled across another Eisen of a woman with a child. The women in both prints are wearing robes made from the same blue and white fan pattern. But it was in the second example that started us on our search for information and graphics dealing with senkō hanabi. Below is an example of that second print found at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Below that is a detail of that image in which we have enhanced the contrast for better viewing.

The image shown above to the left was posted at Wikimedia Commons by Gabriel Pollard and shows a sparkler being used to celebrate Guy Fawkes day. Below that is a 2015 photo of sparklers for sale by hiropiro, also posted at Wikimedia Commons. |

||

|

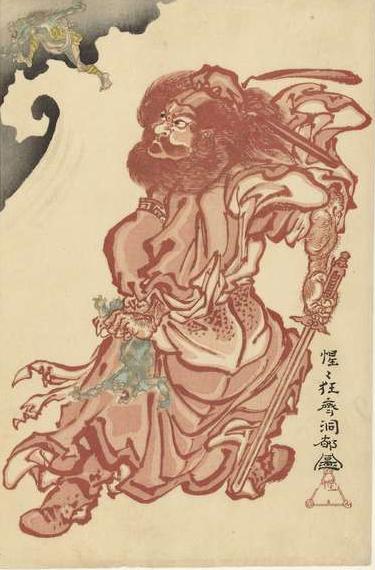

Sennin |

仙人 せんにん |

Also known as a 'sen'. In Hepburn's dictionary - first published in 1867 - it defines this term as "A sort of imaginary beings, who live amongst the mountains; genii, fairy." Sen ni naru means to become a genius. However, most modern dictionaries define it as hermit or wizard. |

||

|

"Persons manifesting the ideals of religious Taoism, who were imagined to have attained supernatural powers, especially immortality, by means of ascetic exercises practiced in remote mountain regions." Similar figures in India, the rishi, shared many of the traits of the sennin. They had psychic powers and could levitate. "In China, adepts were believed to preserve a youthful appearance indefinitely by drinking elixirs containing such ingredients as powdered cinnamon, mica, deer horn, and cinnabar, and allegedly could levitate, ride clouds, and make the wind blow. The concept of [these] xianren was introduced to Japan along with Taoism, and the earliest references to Japanese sennin appear in Nara-period (710-794) legends concerning Ōtomo no Sennin, Azumi no Sennin, and Kume no Sennin." The founder of the Shugendō cult was said to be a sennin. "The term was adopted by Buddhists and occasionally used as a designation for the Buddha, because of his mastery over life and death, but more often for religious figures of great accomplishment who belonged to heterodox faiths." (Source and quotes from: "sennin" by Inokuchi Shōji in the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 7, p. 67)

There is an unusual reference to sennin in Mock Joya's Things Japanese (p. 364): "Sennin (hermits) were... said to have lived on pine needles." This makes a reference on page 63 in Japanese Sword Mounts by Helen Gunsaulus that much more comprehensible in a description of an elaborately worked tsuba: "Beneath an old pine-tree with golden needles stands the Chinese sage, Fung Kan, known in Japan as Bukan Zenji. He is one of the rishi or sennin (sien nung), beings endowed with supernatural powers who enjoy rest for a period after death, being for a time exempt from transmigration.... Bukan Zenjin is always accompanied by a tiger..."

In Ernest Eitel's volume, Hand-book of Chinese Buddhism, Being a Sanskrit-Chinese Dictionary..., originally published in 1888, defined 仙人, here spelled 'richi', are separated into five categories. In India it was believed that a mortal could become an immortal after a short transitional period instead of the 1,000,000 years for the normal transmigration. However, in China the Buddhists and Taoist thought the change could happen immediately. The five classes are: 1) 天仙, the deva rishi, "who are believed to reside in the Seven Circular Rocks which surround Mount Meru; 2) 神仙, spirits who roam about in the air. In Japan these are referred to as shinsen or Taoist immortals; 3) 人仙 are human rishis or immortals who dwell among men; 4) 地仙 are earth rishis or immortals who live in caves; and 5) 鬼仙 or roving demons who form "...a 7th class of sentient beings." (p. 130)

There is a Nō play entitled Ikkaku sennin (一角仙人) or The One-horned Immortal by Komparu Zembō (金春禅鳳: 1453?-1532?). In 1921 when Arthur Waley gave a synopsis of this play and a translation he treated it with some discretion and delicacy leaving the source material somewhat hazy. Waley said: "A Rishi lived in the hills near Benares. Under strange circumstances [Waley added a footnote here - in French - which did little to clarify matters] a roe bore him a son whose form was human, save that a single horn grew on his forehead, and that he had stag's hoofs instead of feet. He was given the name Ekashringa, 'One-horn.' " (Quoted from: The Nō Plays of Japan by Arthur Waley, p. 245) "Under strange circumstances..." ¶ After much digging we found an unadulterated source for this play. Based on a common theme of the seduction of a hermit/celibate by a courtesan says: "In the country of Vārāņasī there was an immortal (sage) living on a mountain. One day in the fall when he was urinating into his bath basin, he caught sight of two deer copulating. Sensual thoughts germinated in him and his seed flowed into the basin. The female deer drank [from the basin] and soon became pregnant. ¶ In due month she gave birth to a baby, who was human except that it had a horn on its head and the hooves of a deer. When the deer was about to deliver, she went to the immortal's dwelling, and she [left the baby there] to be entrusted to the immortal, and then she left." ¶ When the immortal came out of his cave he saw the baby and knew it was his. He raised this hybrid child and educated him in many mystical ways so that the child "...obtained five supernatural faculties." ¶ Later the single-horned figure was climbing the mountain when a torrent of rain came down causing him to slip. "...he fell and injured [himself]. In a rage, he chanted an order to stop the rain. Because of his virtue, all dragons and gods no longer sent rain. Consequently crops failed and people were pining and could not make a living." The local king consulted with his councilors one of whom told him the cause of their problems. So, the king offered half of his holdings to anyone who could make the immortal lose his "five supernatural faculties" and bring back the rain. A famous 'harlot' - Waley's term - said she could if the creature had any human in him and in proof she would come back to the court riding his back. ¶ "The courtesan then hired five hundred carts to carry five hundred beautiful women, and five hundred wagons to carry all kinds of pleasure pills made from herbs and all kinds of strong wine..." They dressed in clothes made from bark making them look like hermits and set up their shelters near the cave of the one-horned creature. He saw them and approached, was charmed and seduced and in the end the 'harlot' asked the rishi to bathe with her. She aroused such passions in him through her touch that he lost his supernatural powers and it began to pour for seven days and seven nights. When the fruit and pills and wine ran out the creature asked for more, but the 'harlot' said there were no more except at her home. However, after they set out in that direction the woman said she was too tired to walk and the creature offered to carry her. ¶ In time the one-horned creature was allowed to return to his home and there he relearned what he had lost and regained his five powers. (Source and quotes: The Water God's Temple of the Guangsheng Monastery: Cosmic Function of Art, Ritual and Theater by Anning Jing, pp. 179-81) ¶ "In the Nō play... the Rishi has over-powered the Rain-dragons, and shut them up in a cave. Shāntā, a noble lady of Benares, is sent to tempt him. The Rishi yields to her and loses his magic power. There comes a mighty rumbling from the cave." (Waley, p.245)

In Traditional Japanese Theater edited by Karen Brazell (p. 68) is an even more cogent description of the theme discussed above: "The tale of a powerful ascetic who, having locked up the rain gods and caused a drought, has his powers destroyed by a beautiful woman is familiar to audiences throughout Asia. In Japan, popular versions found in the Taiheiki (chapter 37) and the Konjaku monogatari (book 5, tale 4), as well as in the Noh play Ikkaku sennin (One-horned wizard)..." When seduced "The wizard joins her dance until he collapses, and the dragon gods, played by child actors, are able to escape from the cave (a stage prop), taunt the wizard... and cause the rains to fall." ¶ A variant on this was written for the kabuki theater, Saint Narukami. It strays considerably from the Nō play.

There is a mention of a sennin in English from a book from 1790, Bell's New Pantheon or Historical Dictionary of the Gods, Demi Gods, Heroes and Fabulous Personages of Antiquity by John Bell (p. 142). The passage says that the 'Budha' "...at nineteen years of age became disciple of a famous hermit called Arara Sennin [阿羅邏仙人]." Engelbert Kaempfer in his 1727 book on Japan said that Buddha left his wife and son to study with this man "...who lived on top of Mount Dandoku. The latter exhorted him to lead an austere life and constantly meditate on heavenly, spiritual subjects, while sitting in particular posture of spiritual contemplation where the feet are twisted and place on top of each other in an unnatural fashion and the hands rest folded in the lap, with the thumbs raised touching each other at the tip."

In 1203 the Shōgun went out on a hunting trip to foot of Mt. Fuji. Near the base of the mountain was a large carve which the locals the Cave of Man. Intrigued the Shōgun sent his bravest warrior, Shirō Tadatsune, into the cave to see what was in there. Tadatsune was armed with a special sword and accompanied by a group of brave companions. The exploration was terrifying and horrific and not all of the band survived. At one point they entered a large cavern with "a pillar of blue ice", a stalactite. "One of the men had said that he had heard this kind of stalactite was a mineral from which the Sennin immortals prepare the nectar of immortality - so he had been told." (Source and quote: Samurai Zen: The Warrior Koans by Trevor Leggett, pp. 84-5)

Above is a blue stalactite from a Polish cave. This photo was posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Tanja5. Maybe they have sennin in Poland too. |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Seno Jūrō Kaneuji |

瀬尾十郎兼氏 せんお.じゅうろう.かねうじ |

Character from the kabuki play "Genpei Nunobiki no Taki" 1 |

||

|

Seppuku |

切腹

せっぷく |

A form of ritual suicide through disembowelment. Also known as harakiri.

The image to the left is a Kuniyoshi print from the Lyon Collection.

|

||

|

Seriage |

迫上

せりあげ |

A trap lift for actors.

"The stage itself, in wing space, position of lighting instruments, facilities for flying scenery and so forth, follows the Western model. However, the stage retains the use of machines which were developed by the Japanese independently of their development in other countries. These are the seridashi, the seriage, and the mawari-butai."

"The first use of the seriage... appeared in 1736." Quotes from: The Kabuki Theatre, by Earle Ernst, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1974, p. 29.

"A half century prior to the revolving stage, various types of traps were introduced to kabuki. Generically, all these devices, which raise actors or scenery up to the stage level through a hole in the floor or lower them out of sight, are called seri, literally 'press' or 'push.' When a trap is raised, this is referred to as seriage, 'push up,' or seridashi, 'push out.' Quote from: Studies in Kabuki: Its Acting, Music, and Historical Context, by Brandon, Malm and Shively, Published by the Institute of Culture and Communication East-West Center, 1978, p. 116.

"During the eighteenth century there was a great development of Kabuki theatre machines, all of which first appeared in the doll theatres of Ōsaka. The first trap-lift for small pieces of scenery appeared there in 1727 and was first used by the Kabuki at the Nakamura-za in Edo in 1736. In 1744 a trap-lift for actors was also installed in this theatre. A larger trap-lift (yatai-seriage) capable of thrusting up large pieces of scenery, such as temple gates and the walls of rooms, appeared in the Chikugo-shibai, a theatre in Ōsaka in 1748." Quotes from: The Kabuki Theatre, by Ernst, p. 53. [We added this while working on our entry on yatai on our Yakusha thru Z page.] |

||

|

Seridashi |

迫出 せりだし |

A trap lift for scenery for the kabuki theater.

"The seridashi is a trap-lift which brings scenery from below to the level of the stage floor and vice versa. This invention of Namiki Shōzō seems to have first appeared in November 1727." (Quote from: The Kabuki Theatre, by Earle Ernst, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu, 1974, p. 29) |

||

|

Setsubun |

節分

せつぶん |

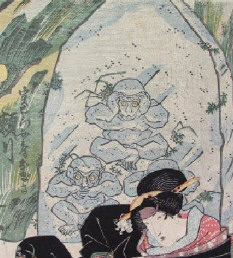

"On the last day of winter, setsubun, the parting of the seasons, people perform a ceremony at temples and in many private houses where they throw beans at imagined or impersonated frightening figures called oni. When they throw the beans they shout: “Oni wa soto, fuku wa uchi” (Oni get out, luck come in)" Quoted from the foreword to Japanese Demon Lore: Oni from Ancient Times to the Present.)

The image to the left shows Kintoki driving out the oni. It is from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and is by Hosikawa Sōri. |

||

|

Setsuwa bungaku |

説話文学 せつわぶんがく |

In the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 7, entry by Douglas Mills, p. 72 it says: "setsuwa bungaku ('tale' or 'anecdotal literature'). Though coined as the equivalent of the Western fairy tale, or märchen, as distinct from densetsu (legend) or shinwa (myth), the word setsuwa now has a very general meaning. Not only are individual items of legend and myth as well as fairy tales termed setsuwa, but so too are the episodes about Chinese history interpolated in the Kamakura-period (1185-1333) war tales, or anecdotes about ordinary life, including the everyday life of courtiers of the Heian period (794-1185). In practice, 'setsuwa literature' is a blanket term used to refer to a number of collections of short tales or anecdotes compiled between 800 and 1300 AD. The category excludes the more literary and lyrical genre of uta monogatari (poem tales). Those collections do not contain fairy tales or myths. They feature the unusual or the remarkable and make much of hte supernatural; but their stories purport to recount incidents that actually happened, or were thought to have happened, in real life. ¶ Many collections deal exclusively with Buddhism, Buddhist miracles, and pious Buddhist figures." |

||

|

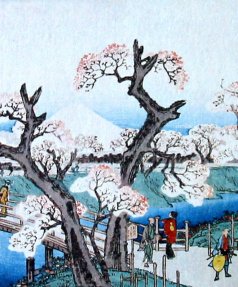

Settsugekka |

雪月花

せつげっか

|

Snow, Moon, Flowers: A popular motif in Japanese art which has its origins in 6th century China intellectual theory. Composed by Xie He [謝赫] the "Six Rules of Painting" were published in three volumes: 'Snow', 'Moon' and 'Flowers'.

Merrily Baird stated: "The Japanese term 'snow, moon, and flowers' (settsugekka) refers to the Three Beauties of Nature, with each of the beauties said to be a reminder of the transience of life."

Source: Merrily Baird, Rizzoli International Publications, Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design, 2001, p. 38.

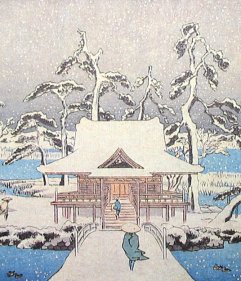

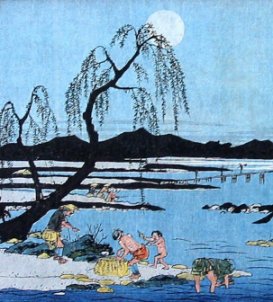

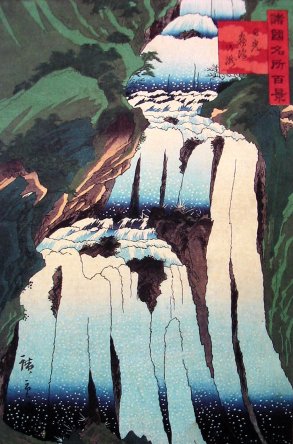

To the left are three details from a series of prints by Hiroshige originally published in ca. 1843. The series carried the title Meisho setsugekka (Famous Places of Snow, Moon and Flowers). |

||

|

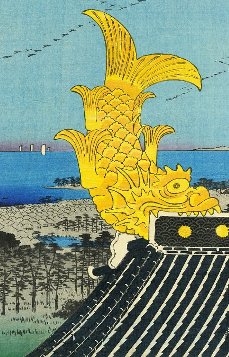

Shachi |

鯱

しゃち |

In the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan (vol. 5, p. 309) it says of Nagoya Castle that "The five-storied donjon was destroyed during World War II, but its exterior has since been reconstructed. Also reconstructed were replicas of its pair of famous golden shachi (dolphinlike sea creatures), almost 3 meters (10 ft.) high and covered with gold scales, which now decorate the gable roof ends of the new ferroconcrete main keep."

This creature was placed on

other rooftops, but this particular golden one is called the kinshachi

(金鯱).

Above is a trimmed detail from a photo by 663highland posted at commons.wikimedia. It is of one of the shachi at Okayama Castle.

Many dictionaries refer to this kanji character as a shachihoko (しゃちほこ) or "fabulous dolphin-like fish". Jim Breen gives it as 鯱鉾 a "mythical carp with the head of a lion and the body of a fish" which is an auspicious symbol of protection and well-being.

A large kinshachi was displayed at the Vienna International Exhibition in 1873 and proved to be an enormous success. (Source: Modern Japanese Art and the Meiji State: The Politics of Beauty by Doshin Sato, p. 111.

The image to the left is a detail from a Hiroshige II print. |

||

|

In the DK Eyewitness Travel Guide: Japan by John Benson (p. 208) describes these rooftop decorations as "Dolphin-like shachi-gawara motifs on the roof are of a mythical beast believed to protect the main tower from fire."

A tip: If you wish to see more, i.e., the most examples of this motif try copying and pasting the kanji characters for shachi-gawara 鯱瓦 into a Google image search. The results are startling. Don't let your lack of Japanese language deter you.

In the 1903 Up-to-date Guide for the Land of the Rising Sun by H. Hotta (pp. 89-90) it says: "The Dolphins measure 8.7 feet in height and 7.3 feet in circumference. It is said to have been made from old Japanese coins, valued some 3,200,000 yen."

At the Allerton Park in Monticello, Illinois is a property bequeathed to the University of Illinois. Near the Sunken Garden is a set of pylons surmounted by copies from ca. 1931 of the Nagoya Castle shachi. The photos abaove and below were both found at Flickr. The top one was posted by Broken Thoughts and the one below by Tau Zero. Both have been trimmed. "On the pylons in the Sunken Garden, looking very much like glittering sea creatures diving into a vast subterranean world, surfaces modeled in wonderful deep and shallow designs, teeth huge and fearsome, are sixteen guardian fish, reduced-scale versions of originals at Nagoya Castle, Japan. Several are recent reproductions necessitated by thefts, but most are the original bronzes covered by three layers of gold leaf (now badly worn) that Allerton had made by Yamanaka and Company, Tokyo. ¶ Representations of these mythological, scaly-armored aquatic fire protectors, called shachi, were used as roof ornaments in Japanese palaces and castles, and until its destruction in World War II, Nagoya Castle possessed the most famous pair: a male and female mounted atop the high inner tower, first created in the seventeenth century and remade several times, in 1726, in 1827, and again in 1846. (The castle, built c. 1610 was reconstructed in 1959.) The postwar versions are of copper covered with eighteen-karat gold mixed with bronze, but the nearly nine-foot-high originals were of wood plated with lead and then encased in a layer of gold." Quoted from: A Guide to Art at the University of Illinois: Urbana-Champaign, Robert Allerton Park, and Chicago by Muriel Scheinman, pp. 125-26.

In Architecture and Authority in Japan by William Howard Coaldrake (p. 128) it says that "...from the time of Azuchi Castle [shachi] became a ubiquitous presence on all castle roofs."

There is a kabuki play from 1782 called Keisei Kogane no Shachihoko. According to a review in The Japan Times from 2010: “Keisei Kogane no Shachihoko” was an exciting tale that Gohei [the playwright] staged in appropriately striking ways. Its popularity led to a remarkably long run at theaters and to establishing Kakinoki Kinsuke as a household name. The legend of Kinsuke riding a kite to the top of the Nagoya Castle in order to steal the gold shachihoko remained a popular theme in Japanese theater and literature throughout the 19th century. Mysteriously, though, the play fell out of favor and ceased to be staged. |

||||

|

|

||||

|

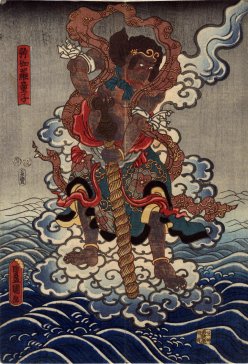

Shaka |

釈迦

しゃか |

This is the Japanese name for the historical Buddha Shakyamuni 563 BC to 483 BC. His is also referred to as Siddhartha.

|

||

|

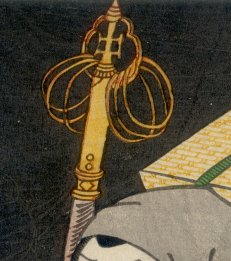

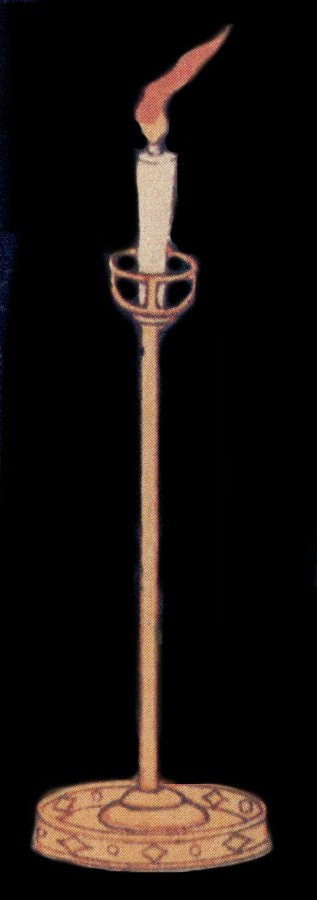

Shakujō |

錫杖

しゃくじょう

|

"...a wooden staff with metal cap on which a metal ring is loosely hung so that a jingling noise is made in walking. This noise is intended to warn beetles, snakes, and other small creatures on which the monk might possibly tread of his approach so that they can get out of the way."

Quoted from: The Shambhala Dictionary of Buddhism and Zen, p. 192.

A pilgrim's staff is also referred to as a kongodue (金剛杖). Because it warns creature of its approach it is known in China as an alarm staff. But the jingling serves another function in that it is meant to drown out all other worldly sounds from the ears of the carrier.

The Buddha was said to have used a sandalwood staff with pewter head and rings.

Source: Chinese Symbolism and Art Motifs, by C.A.S. Williams, Castle Books, 1974 edition, p. 5.

|

||

|

Shamisen |

三味線

しゃみせん

|

"A three-stringed plucked lute that was originally associated with the urban world of the pleasure quarters and theaters of the Edo period (1600-1868) and later became a concert instrument as well. It is called samisen in the Kyōto-Ōsaka area and the sangen when used in classical chamber music."

The shamisen may have its origins in a similiar instrument found in China, but definitely is traceable to one from the Ryūkū Islands. "Both the Okinawan (sanshin or jamisen) and the Chinese (sanxian or san-hsien) forms are still used today, but they differ greatly from the instrument used in Japan."

Shamisens vary in length from 3.6' to 4.6' according to the sound desired. "They are generally distinguished by the thickness of their unfretted fingerboard, but other differences are found in string gauges, bridge weights, body sizes, and the design and size of the plectrums (bachi). The wooden quince, and the heads which cover the front and back of the body are cat or dog skin. Pegs and plectrums are ivory, wood, or plastic. Strings are twisted silk or nylon." Of course the plastic and nylon parts were not available during the Edo period.

Source and quotes from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan entry by William P. Malm (vol. 7, pp. 76-7) |

||

|

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Eizan showing a geisha holding her shamisen. The detail below shows what is probably intended to be an ivory plectrum or bachi (撥).

"A geisha is often called a neko [i.e., cat]; but it is because cats' hides are used in making shamisen, their musical instrument. But some say that it is because a geisha is also to be petted."

Quoted from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese (p. 114)

According to Mock Joya the shamisen is of unknown origin and may have originated in Siam. It was introduced into Japan via the Ryūkūs during the Eiroku era (1558-1570). "It was a biwa (lute) player named Nakashoji who took interest in the new instrument when it first came to Sakai." In the Ryūkūs it was called a jahisen (snake-skin string) because that was what was used to cover the sound box. There it was played with a bow, but Nakashoji replaced that with the plectrum he used to play the biwa. He also made sound changes. "As it was impossible to obtain snake skins for the instrument, he covered it with cat-skin." Source and quotes from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese (pp. 494-5). |

||||

|

|

||||

|

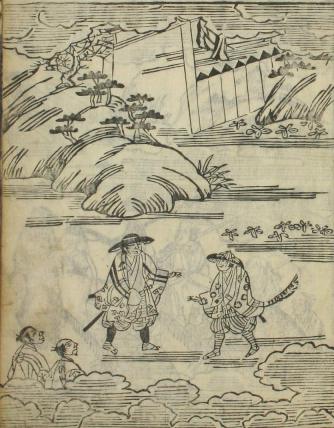

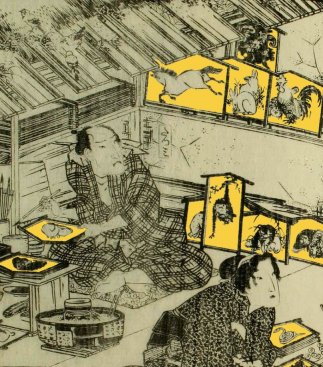

Shank's Mare |

|

A classic, serial, comic novel by Jippensha Ikku ( (1765-1831: 十返舎一九 ) which first appeared in 1802. It follows the adventures of two "amiable scoundrels", Yajirobei and Kitahachi, as they travel from Edo to Kyōto via the Tōkaidō road. The title in Japanese is the Tōkaidō Hizakurige ( 東海道膝栗毛). Although this book is a bit ribald it should be a must read for anyone interested in the culture of that age.

The original publisher in Edo may have been Yamashiro-ya Sahei (山城屋佐兵衛).

For anyone who is interested 'traveling by shank's mare' according to the Merriam Webster dictionary is traveling on 'one's own legs.' This expression dates back to ca. 1795. This first translation into English by Thomas Satchell "...was published by subscription in Kobe in 1929." For that reason it had a very small audience until it was reprinted in 1960 by Tuttle. This copy is from 1992. Satchell did not permit his name to appear on the title page. It shows up at the end in Romaji. He moved to Japan in 1899 and became editor of the Yokohama Japan Herald in 1902. Despite being married to a Japanese woman and having two daughters he was arrested and interned until the end of the war. He died in 1956. Ikku added his preface 12 years after the first part was published. In it he states: "You will find many bad jokes and much that is worthless in the book, which is moreover overburdened with many poems where sound and sense conflict. Along with this there is much of the one-night love-traffic of the roads..." |

||

|

It is said that Basil Hall Chamberlain called this novel "the cleverest outcome of the Japanese pen." James Seguin De Benneville in his 1906 volume Sakurambō called Jippensha Ikku the Japanese Rabelais. I have read Rabelais and would consider this a compliment. Some of my friends wouldn't agree. In 1908 William George Aston noted that Ikku's novel was printed in 12 parts starting, as we said, in 1802 and finishing in 1822. "It occupies a somewhat similar position in Japan to that of the Pickwick Papers in this country [i.e., England], and is beyond question the most humorous and entertaining book in the Japanese language. (A History of Japanese Literature, published by W. Heinemann, 1908, p. 371) Later Aston adds: "Still, people of nice taste had better not read the Hizakurige." To this he piles on: "The great drawback to the fun of the Hizakurige is that it is unrelieved by any serious matter." Here Aston is comparing Ikku to Shakespeare. (p. 373)

The finest example of the kokkeibon (滑稽本) or 'funny book' genre may be this novel. "The work that established the importance of the kokkeibon was unquestionably Tōkaidō Dōchū Hizakurige (Travels on Foot on the Tōkaidō) by Jippensha Ikku." Published in 43 volumes because the "...public demand again and again compelled Ikku to prolong the adventures of his irrepressible heroes, Kitahachi and Yajirobei. These utterly plebeian, typically Edo men are full of a lively if coarse humor, and have a knack of getting involved in comic and usually unsuccessful intrigues with women. The readers' interest in bowel movements was apparently inexhaustible; the number of references to soiled loincloths suggests that the subject was particularly enjoyed, and indicate also the general level of humor." Neither of the heroes cares about honor or reputation and are driven by lust. (Source and quotes from: World Within Walls: Japanese Literature of the Pre-Modern Era 1600-1867, by Donald Keene, published by Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1976, pp. 412-13) |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Sharebon |

洒落本 しゃれぼん |

"Sharebon, or "witty books," which first appeared in the Kamigata cities during the cultural boom of the 1740s, were prose works modeled on erotic pamphlets from China. They portrayed the licensed quarter and its clients, pointedly satirizing those who bungled the local etiquette. And they used dialogue and other verbal and visual devices, rather than kibyōshi-style pictures, to evoke the world of their characters. They later became popular in Edo, with Santō Kyōden publishing them to great effect until he collided with Sadanobu in 1791. By the 1800s, sharebon had evolved into less witty, more melodramatic, and more widely popular stories of the romantic entanglements and social quandaries of the quarter, focusing on "the personal, non-professional relationships among courtesans, patrons, entertainers, and brothel keepers." " Quoted from: Early Modern Japan by Conrad Totman, p. 419. |

||

|

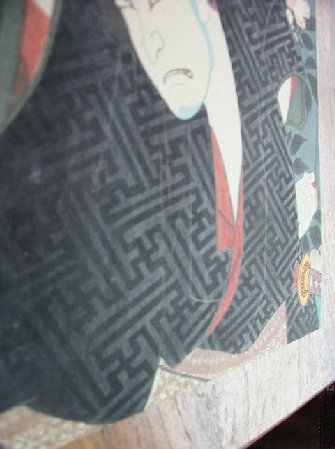

Shibaraku |

暫

しばらく |

"Stop Right There!": One of the greatest and most dramatic moments of the kabuki theater occurs when the hero is walking down the hanamichi or walkway toward the stage dressed in a spectacular persimmon red costume. Just as a murder is about to take place he yells "Shibaraku".

This role was created by Ichikawa Danjūrō II (1688-1758). In time this became the opening act of the season opener no matter what play was being performed. "Just a Minute! is one of the finest examples of the Danjūrō family style (ie no gei), its hero powered by godlike qualities of magnificence, might, and theatricality but also contained roles of every type (yakugara), thus effectively presenting the members of the new troupe through the display of their varied talents." (Quote from: Kabuki Plays on Stage: Brilliance and Bravado, 1697-1766, vol. 1, edited by James R. Brandon and Samuel L. Leiter, University of Hawai'i Press, 2002, p. 44)

"More than a play, Shibaraku is a time-honored ritual based on the folk tradition of good repelling evil. The semihumorous plot, replete with witty wordplay, reflects the pleasure-seeking spirit typical of the common people in the Edo period." (Quote from: The Kabuki Guide, by Masakatsu Gunji, Kodansha International, 1987, p. 122)

The detail to the left is from a print by Toyokuni I.

The term shibaraku can be translated a number of ways: little while; Wait A Second!; Wait A Minute!; Wait!; Stop Right There!; and probably a few more I am not aware of. |

||

|

Shichifukujin |

七福神

しちふくじん |

The Seven Gods of Good Luck: Ebisu, Daikoku, Bishamon, Fukurokuju, Hotei, Juroji and Benten. "As W. E. Griffis tells us in his 'Religions of Japan' (p. 216) 'Ryōbu Buddhism is Japanese Buddhism with a vengeance. Take for example, the little group of divinities known as the Seven Gods of Good Fortune which forms a popular appendage to Japanese Buddhism and which are a direct and logical growth of the work done by Kobō as shown in his Ryōbu system.' These popular deities, known by the name Shichifukujin, are nominally a Buddhist assemblage, but, in truth, they come from four distinct sources: Shintoism, Buddhism, Brahmanism, and Taoism. They are in evidence in almost every Japanese home, certain of them appearing on the 'god-shelf.' "

In a 1922 publication by the Field Museum in Chicago said: "The Seven Gods are not regarded with the awe and dignity that one would think appropriate for deities. They are very often treated in a humorous manner, and commonly Bishamon is pictured as making love to the goddess Benten."

Burleigh Mutén and Rebecca Guay in their Goddesses: A World of Myth and Magic say "The Buddhist people say that if you purchase a picture of the ship and place it under your pillow that night, Benten will reward you with lucky dreams."

The image to the left shows the 7 gods in the treasure ship or takarabune.

Laurence Binyon in his Japapnese Colour Prints wrote on page 127 that "...the Seven Gods of Good Luck, who are universal themes of playful art." |

||

|

Shichigosan |

七五三

しちごさん |

The Britannica says: "Shichi-go-san, (Japanese: “Seven-Five-Three”), one of the most important festivals for Japanese children, observed annually on November 15. On this date girls of three and seven years of age and boys of five years of age are taken by their parents to the Shintō shrine of their tutelary deity to offer thanks for having reached their respective ages and to invoke blessings for the future. In former times the day was also marked by five-year-old boys of the samurai class being dressed in a hakama (pleated, divided skirt) and presented to their respective feudal lords, seven-year-old girls wearing the formal obi (stiff sash), and the three-year-old girls having their hair arranged on top of their heads, all for the first time." |

||

|

Shide |

紙垂

しで |

The zig-zag, cut paper streamers attached to a sacred wand made from a sakaki (榊) tree used in Shinto rituals to ward off evil spirits. They also are added to shimenawa which are the twisted straw rope which indicate a sacred space.

(See haraegushi, tamagushi, sakaki, nusa and shimenawa.)

The photo to the left was posted at Flickr by Thomas. |

||

|

Shigenobu |

重宣

しげのぶ |

Early name of Hiroshige II 1, 2

I am so sorry. I made a terrible mistake several years ago and it wasn't until now that I realized my error. This Shigenobu is not 重信. That Shigenobu had actually been a pupil and son-in-law of Hokusai and not Hiroshige. This Shigenobu had been the son-in-law and pupil of Hiroshige and his name is represented by the character 重宣. If that weren't confusing enough there were at least five print artists of different eras who used 重信.

In a February 7, 1922 sale catalogue of the Alexis Rouart collection written by Frederick W. Gookin it says on p. 262 "Pupil and son-in-law of Hiroshige. Personal name Sukuki [sic] Chimpei. First studio name Shigenobu; also signed Ichiyūsai. In February 1859 (first month Ansei 6) became Hiroshige II. In 1865, he divorced his wife that she might marry his fellow pupil Shigemasa, to whom he then gave the Hiroshige name, taking that of Risshō for himself, and retiring to Yokohama. He also signed as Hirochika II in his later years."

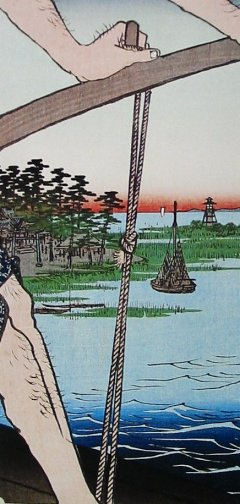

The image to the left is by Hiroshige II, formerly known as Shigenobu. As one of his major critics had said "Some of the work of Hiroshige II is very good..." Very good indeed. This print is a masterpiece. |

||

|

Shigenobu/Hiroshige II has received some very bad press. The stage was set by the first decades of the 20th century to look rather unkindly on the work of Hiroshige's artistic heir. Writers like Arthur Davison Ficke were hardly sparing in their criticisms. ¶ We know that some of Hiroshige's last series of prints, '100 Views of Edo', was published posthumously and that several of the prints were designed by Shigenobu. In his Chats on Japanese Prints Ficke placed this series in a section entitled 'Fifth Period: The Downfall' and described the views of 'Yedo' as having "...119 plates, including, besides much rubbish, 25 masterpieces". (Published by Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1917, p. 393)

Ficke continued to disparage the late works by Hiroshige which Shigenobu helped produce. It would seem most of Ficke's criticisms were aimed at the latter: "...certain of the plates are of so banal a character that it is impossible to believe them to be from the great man's hand. Doubtless the distinction between the work of the two artists cannot always be drawn with certainty; but as a general rule we may regard the work as that of Hiroshige II if we find the figures stiff and wooden, if the composition is lacking in any central unity, or if some large ugly object is thrust into the foreground with the hope of thus putting the background into its proper relative place." (Ibid.) ¶ Ficke wasn't totally unkind to Shigenobu and did throw him a bit of a bone - a very qualified bone. "Some of the work of Hiroshige II is very good; upon the accidental destruction of one of the plates of the 'One Hundred Yedo Series,' he produced a new design that is admirable. But he lacked originality, and at his best merely trod in the footsteps of his master. Most of his designs are flat and uninspired. About 1865 he fell into disgrace, and moved to Yokohama, where he gave up his name, and is said to have worked henceforth under the name of Hirochika II. He died in 1869." (Ibid., pp. 397-8)

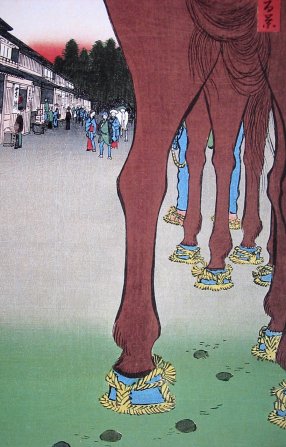

Five years after Ficke dumped on Shigenobu Basil Stewart tried to put the last nail in the coffin. Stewart conceded that Hiroshige claimed on the title page that this was the "masterpiece of his life", but Stewart truly questioned this conclusion. He claimed that certain prints in the series could only be by Shigenobu because the master never would have created such inanities. He referred to the "rear view of a horse" and the "boatman with the hairy legs" and others as being "...equally catastrophic" and could only be blamed on Shigenobu whose work displayed a crudeness which could only be his own. Stewart even believed that Shigenobu designed an 1855 Tokaido series which Hiroshige then put his signature to. (Source: A Guide to Japanese Prints and Their Subject Matter, by Basil Stewart, originally published by Dutton, 1922, p. 22)

On page 23 Stewart said: "Prints in which some large object, such as a tree-trunk, the mast of a ship, the body and legs of a horse, is thrust prominently into the foreground, blotting out the view, and thus spoiling the whole effect of the picture, may generally be ascribed to Hiroshige II; the method of indicating the foliage of trees may also sometimes serve to distinguish between master and pupil." |

||||

|

||||

|

However, not everyone has

agreed wholeheartedly with Ficke and Stewart's appraisals. In the Brooklyn

Museum catalogue of the "100 Views of Edo" it states: "Hairy legs so

prominently placed evoke distaste among Western scholars of Hiroshige's work

and hence a negative reaction to the print that is not found in Japanese

literature on the artist." (Quoted from: One Hundred Views of Edo: Woodblock

Prints by Ando Hiroshige, by Mikhail Uspensky, Parkstone Press, 1997, p.

164) ¶ Uspensky notes that scholars/connoisseurs who found the hairy leg

offensive found the rear view of the horse even more 'vulgar'. Not only were

they put off by the perspective of where the viewing must be standing or

squatting but also by the horse shit droppings seen on the ground. Uspensky

doesn't even mention the horse's scrotum which is clearly visiible. No

wonder they wanted to blame Shigenobu for this breech of good taste. In the 19th century John Ruskin, the English artist and critic, who was raised in stately homes filled with magnificent Greek and Roman statuary, married an incredibly beautiful young woman. However, it is said that on their wedding night Ruskin was unable to consummate the marriage when he realized that his new bride had pubic hair. The statues of ancient goddesses didn't have any and so he was repulsed that his 'goddess' would. They divorced or got an annulment or some such thing and she went on to marry the painter John Everett Millais who was obviously less easily offended or if he was he was able to overcome his personal disgust. A personal note: I have a rather large library of books dealing with Japanese art and culture. Basil Stewart's A Guide to Japanese Prints and Their Subject Matter and don't recommend it when asked. Years ago when I first worked for a man who sold Japanese prints he had a major customer who thought Stewart wrote the bible on them and believed every word of it. He quoted it often and used it to guide his purchases. My boss sold or gave away copies of Stewart's book to anyone who wanted them. He, himself, had never read it. He told me so. As if the confusion over who did what were not enough I thought you might want to compare the signatures of the master and his pupil. I have posted two typical examples below. The differences between them are incidental. Fight the urge to niggle or quibble here. Don't even quibble about niggling. There are many others which could have been posted which would be even closer and then absolutely indistinguishable. |

||||

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

Shigoki |

志ご貴

しごき |

A sash of soft cloth tied under the obi. It can be used to tie up flowing robes or to tuck them in whenever necessary - like when one is wading through water.

Nelson gives the kanji for shigoki as 扱. It has many other disparate meanings but here is defined as a woman's undergirdle or waistband. I suspect that this is the more appropriate character, but don't know for sure. (The New Nelson Japanese-English Character Dictionary, p. 476) |

||

|

Shiitake tabo |

椎茸髱

しいたけたぼ |

A hairstyle "...with the sidelocks drawn out in 'mushroom' shapes."

Quote from: The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, text volume, p. 150.

I won't swear to it, but I think the detail from the print by Toyohiro to the left illustrates an example of a bijin with a shiitake tabo hairstyle. |

||

|

Shika |

鹿

しか

|

Deer have an ancient connection with religious belief system throughout Eastern Asia. In China Taoists thought that deer were able to find the Fungus of Immortality. In Japan they came to be associated with the kami or gods. In fact, deer are often seen as companions to two of the Seven Propitious Gods.

Fake deer heads were often donned like masks for dances during festivals and antlers became a symbol of strength and virility. Stylized representations adorned the helmets of warriors or were used in family crests. Even the wearing of deer skins was thought to be empowering.

Shamanistic divinations were made from deer bones. Pulled from a fire and allowed to cool the cracks were read, i.e., interpreted. The Chinese practiced the same art but with bones and shells of other creatures.

The image of the deer on the green grass to the left and on top is from a photo I shot from my balcony here in Port Townsend, Washington. The image in the center is a detail from a 20th century print by Koitsu. The one on the bottom was sent to me by a correspondent in Maine. Thanks D! |

||

|

Shikake-e |

仕掛け絵

しかけえ

|

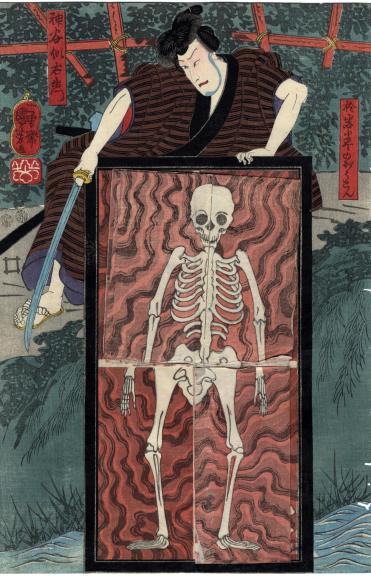

A mechanical print - Extra flaps of printed paper are attached to an image. As they are manipulated a different image will appear. The example to the left come from a Kuniyoshi print in the Lyon Collection. The full range of this particular print provides four different images. Quite a remarkable feat. Below is the same print in another one of its forms. Click on that image to see all of the variations.

Some sources refer to this type as a 'trick print'. |

||

|

|

樒

しきみ |

An evergreen plant, Japanese star anise, used during ritual suicide ceremonies. See our entry on seppuku. Branches of these plants were placed at grave sites, too.

In 'Foxfire: The Selected Poems by Yosa Buson A Translation' by Alan Persinger at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee it says:

No totomo ni

In a burnt field

To the left is a photograph of a shikimi plant in bloom. It comes from the web site operated by Shu Suehiro. The one above is was posted at Wikimedia commons by hurum.koh. |

||

|

Shima |

縞

しま |

Stripes - a common fabric pattern |

||

|

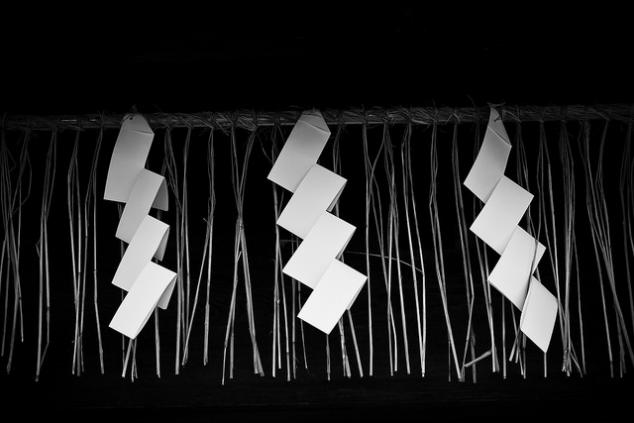

Shimenawa |

七五三縄 or 注連縄

しめなわ

|

Braided rice straw ropes which have the power to keep evil spirits away. Also, for Shintoism, it marks a sacred spot or presence of a kami, i.e., spirit - such as a shimenawa draped around a tree or rock.

Joseph Campbell says about shimenawa "...the august rope of straw that was stretched behind the goddess [Amaterasu] when she reappeared, symbolizes the graciousness of the miracle of the lights return. [The sun goddess had locked herself away in a cave in a fit of pique. It plunged the universe into darkness. The other gods tricked her into leaving her seclusion and blocked her retreat with a shimenawa.] The shimenawa is one of the most conspicuous, important, and silently eloquent, of the traditional symbols of the folk religion of Japan. Hung above the entrances to temples, festooned along the streets of the New Year festival, it denotes the renovation of the world at the threshold of the return. If the Christian cross is the most telling symbol of the mythological passage into the abyss of death, the shimenawa is the simplest sign of the resurrection. The two represent the mystery of the boundary between the worlds - the existent nonexistent line." (The Hero with a Thousand Faces, New World Library, 2008, p. 184)

In a section on straw in Wrapping Culture: Politeness, Presentation and Power in Japan and Other Societies by Joy Hendry (Oxford University Press, 1993, p. 43) she states that "....straw has also been used for many ritual purposes. Clearly visible all over Japan, for example, are the large straw plaited ropes, or shimenawa, which hang in the archways at the entrance to shrines... These serve to mark off the sacred space inside, and smaller versions of them may be used to give ritual value to the objects. One example is the adornment with straw of the tai, or sea bream, which often forms part of a bride's betrothal gifts. A thin straw rope, decorated with paper as mentioned above, is used to mark off sacred space for the ceremony preceding the construction of private houses and many public buildings, and in preparation for festivals in some parts of the country such a rope is hung around the whole district.

The image to the left below is a detail from a print by Toyokuni III in the Lyon Collection. |

||

|

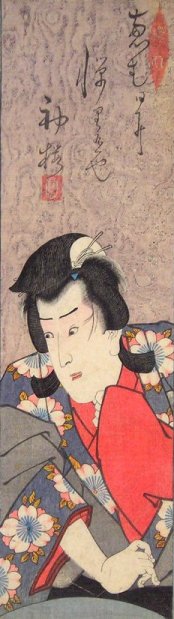

Shini-e |

死絵 しにえ |

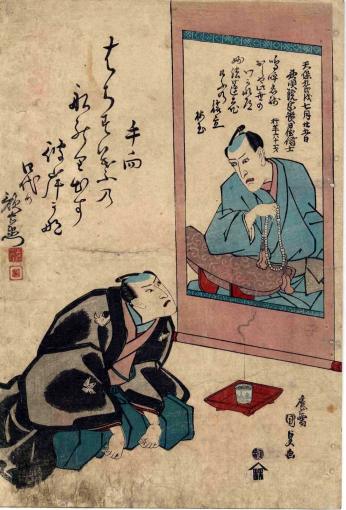

"Death Print" or memorial print: Literally a death (死) picture (絵). They had also been referred to earlier as tsuizen-e (追善絵). This term has a very clear association with a Buddhist service in commemoration of the anniversary of a death. 1, 2

The term shini-e did not come into general use until about the middle of the 19th century. Source: "Memorial Portraits of Kabuki Actors: Fanfare in the Floating World" by Christine M. Guth, Impressions, #27, 2005-06, p. 25.

Kunisada shini-e from Ritsumeikan University

"The term shini-e has been commonly used since the 1850s to refer to a posthumous portrait in woodblock-printed form of a musician, sumo wrestler, artist or most often, kabuki actor, but its modern usage varies. (Although many courtesans were celebrities during their lifetime, there are no shini-e of them - probably because they did not enjoy a large enough following to justify the cost of producing a commemorative print.)" (Ibid., p. 23)

Guth also noted that the standard shini-e have "...vital statistics including the actor's name and date of death, posthumous Buddhist name (hōmyō), mortuary temple and death poem (jisei), information that gives the image ritual connotations. These connotations are underscored by the term tsuizen that appears on some posthumous portraits. Shorthand for tsuizen kuyō, this alludes to the Buddhist memorial services (kuyō) for transferring merit (tsuizen) to the deceased so that they will be assured an auspicious rebirth." (Ibid.) |

||

|

"The first shini-e are thought to have been produced in 1777 in memory of the actor Ichikawa Yaozõ II (1735-1777). A few further recorded examples from the 1780s and early 1790s are also known, but a posthumous portrait of Danjúrõ VI (1778-1799) by Utagawa Kunimasa (1773-1810) is the earliest surviving work with the defining features of shini-e...The actor wears a robe of geometric design beneath the stiff, sleeveless coat and pleated trousers (mizukamishimo) of formal samurai attire. His head is turned to reveal his distinctive profile with its pronounced nose and jutting chin. The iris he holds in his right hand is an allusion to the fifth month, when he died. His professional name, Ichikawa Danjūrō, followed by the word tsuizen, ap- pears to the right, with the artist's signature and publisher's seal below this. A poem referring to his untimely death and purporting to be by Danjūrō himself is inscribed above and around his head and shoulders, its downward movement reiterating that of the decorative flow of ink from the upper edges of the page." (Ibid., p. 25) |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Shini sōzoku |

死に装束 しにしょうぞく |

Light blue court robe worn for burial or suicide 1 |

||

|

Shinkyō |

神橋 しんきょう |

The Sacred Bridge at Nikkō. "One day, while Shōdō Shōnin was on a journey, he saw four strange-looking clouds rise from the earth to the sky. He pressed forward in order to see them more clearly, but could not go far, for he found that his road was barred by a wild torrent. While he was praying for some means to continue his journey a gigantic figure appeared before him, clad in blue and black robes, with a necklace of skulls. The mysterious being cried to him from the opposite bank, saying : " I will help you as I once helped Hiuen." Having uttered these words, the Deity threw two blue and green snakes across the river, and on this bridge of snakes the priest was able to cross the torrent. When Shodo Shonin had reached the other bank the God and his blue and green snakes disappeared." Quoted from: Myths and Legends of Japan by Frederick Hadland Davis, p. 242.

Above is a photograph posted at Wikipedia commons by Fg2.

For more infomation see our entry on Yoshitoshi print of Tokugawa Ieyasu on this bridge. |

||

|

Shintai |

神体

しんたい |

A physical object in which a kami, i.e., god, is said to be exist. 1 |

||

|

Shintō |

神道 しんどう |

"Shinto is a relatively recent term applied to alleged native cults and thought. It is not to be understood as an independent and unified indigenous religious system. Strongly shaped by Buddhism and other continental, especially Chinese, traditions, it was only in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that scholars tried establish a Shinto religion and a state ideology by isolating what they believed to be unspoiled native elements from the combined Shinto-Buddhism religion that had, until then, pervaded the religious life of most Japanese. A matsuri perspective on Shinto especially allows one to detect continental religious practice probably imported by the kikajin immigrants before the seventh and eighth centuries. It was Buddhism, no doubt, that helped shape Shinto when it was at best a body of disparate tribal and imperial cults." Quoted from Matsuri: The Festivals of Japan by Herber Plutschow, p. 4.

The Oxford Dictionary online defines it as "A Japanese religion dating from the early 8th century and incorporating the worship of ancestors and nature spirits and a belief in sacred power (kami) in both animate and inanimate things. It was the state religion of Japan until 1945." |

||

|

Shinzō |

新造 しんぞう |

The lowest order of official prostitutes who also attend to the needs of the highest ranking courtesans. 1 |

||

|

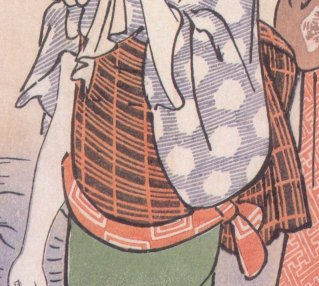

Shiokumi |

汐汲み

しおくみ |

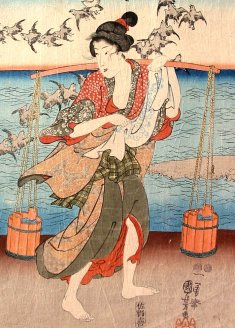

Salt gathering or gatherer: Enden (塩田) or salt fields were historically the main source of salt in the Japanese diet. Saltwater from the seaside could be boiled down or sand deposits laden with copious amounts of salt could be doused with seawater and then boiled to render an edible product. |

||

|

Years ago I attended the lectures of a visiting scholar, Raymond Mauny, who stressed the importance of the ancient salt trade routes in West Africa. These traversed the Sahara at great peril. However, salt was so highly valued that it was traded for gold and other precious items.

In 1930 Gandhi led a group of men on a march to the sea to gather salt in contravention British orders. The British had imposed a salt tax which Gandhi thought iniquitous.

"When an unwelcome visitor finally leaves the house, the old-fashioned housewife will hurry to the kitchen and, taking a pinch of salt, scatter it all over the house entrance." This is an act of purification which always overpower evil. Sumo wrestlers toss salt before a match to drive away evil spirits and as an indication that they will fight fairly. Even attendees at funerals purify themselves with salt before reentering their homes.

Source and quote from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, pp. 305-6.

The story of the salt gathering maidens was a popular theatrical theme. In short: "Literary works based on the legend of the sisters Matsukaze [松風] and Murasame [村雨] began with the medieval nō play Matsukaze. In the Edo period, the story develops in many directions, but plays for the puppet and Kabuki theatres are known as 'Matsukaze' pieces'... When performed as a Kabuki dance, the title is always 'Shiokumi' (Drawing Brine). Ariwara no Yukihira [在原の行平], who had been exiled to Suma, falls in love with both the sisters Matsukaze and Murasame, who live by the sea making salt from the brine. When he departs to go back to the Capital, he gives them his golden court hat and hunting cloak..."

Quote from: The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, entry by Timothy Clark, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, text volume, p. 155-6. |

||||

|

|

||||

|

Shiori |

栞

しおり |

Bookmark

There was a time in the 18th century when the Japanese were believed to be the most literate people in the world. Naturally this would call for a lot of bookmarks. Whereas this might not seem particularly pertinent to a discussion of ukiyo prints it is. Many artists, such as Utamaro, often used a bookmark cartouche to post the title of a print series. In time some artists even designed whole prints mimicking the shiori itself.

The cartouche seen above is a detail from a print by Kunisada. (You can see the whole print by clicking on the number in the column to the right.) The image below is a detail from a print by Toyokuni III created in the shape of a bookmark. That image was sent to us by our great contributor Eikei.

Thanks 英渓!

Take a look at the prints you own. If your collection is large enough at least one of them will probably have a bookmark cartouche on it. Now you know what that form is called. That is, assuming my information is correct. Don't quote me.

Shiori-gata (栞形) is the precise term used to indicate a bookmark-shaped cartouche. 1

|

||

|

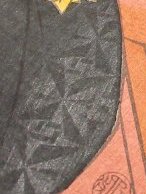

Shippō |

七宝

しっぽう

|

The Seven Treasures composed of gold, silver, pearls, agate, crystal, coral and lapis lazuli.

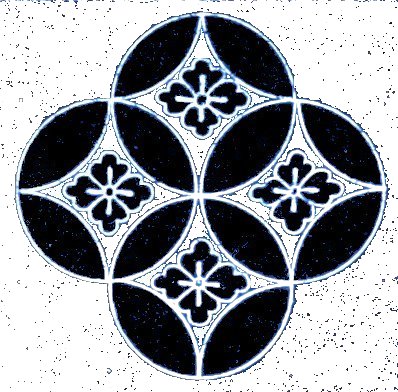

Shippo also has two other related meanings. The first is a Japanese term for cloisonné and the second is a decorative motif which displays none of the precious items listed above, but consists only of interlocking circles. See the image detail from a Kiyonaga print to the left.

"The shippo design appeared in the late Heian period as an abstraction from a large overall pattern of overlapping circles, the overlap being exactly equal on all four sides. Its name appears to derive from one of those inimitable Japanese puns, this one shi-ho, or 'four directions.' "

Quoted from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 134.

I have added the two family crests or mons at top left and below in order that you can see two variations on this motif.

This pattern is also referred to as shippo tsunagi (七宝繋).

|

||

|

Shiraki |

白木 しらき |

Plain or unfinished wood. "...the eye attuned to plain, unfinished shiraki seems a uniquely Japanese sensibility. Elsewhere in the world, the taste for woodgrain runs strong.... Yet probably no other culture exhibits such fondness for fresh, clean, planed wood surfaces. Very recently, some furniture coming out of Scandinavia in particular has begun to feature plain pine for its aesthetic value, but this is largely due to a Japanese influence on the vocabulary of Modernism. ¶ Just how and when the Japanese came to this appreciation of unfinished wood is difficult to pinpoint. The most that can be said is that it relates to certain indigenous religious beliefs existing on the Japanese archipelago from before the transmission of Buddhism in 538, and specifically to the cult of purity and abstinence from defilements. The Grand Shrine of Ise... and other shrine architecture is of plain wood, as are almost all ritual implements of Shinto. For fundamental to their design was the understanding that all utensil objects, architecture included, were to be discarded after use. This clearly ties in with the nature of woods such as Japanese cypress and cryptomeria — fragrant and beautifully bright when new, but all too quickly soiled. ¶ While any conscious valuation of unfinished wood that existed prior to the influx of Chinese culture was no doubt limited to a priest-aristocracy, such awareness still remains strongly rooted in the cultural life of the Japanese people even today." Quoted from: Traditional Japanese Furniture by Kozuko Koizumi. |

||

|

Shiranami-mono |

白浪物 しらなみもの |

Stage works with thieves and lowlifes as the heroes |

||

|

Shiratama |

白玉 しらたま |

A courtesan of the Tamaya brothel 1 |

||

|

Shirizaya-no-tachi |

尻鞘の太刀

しりざやのたち |

"...a removable fur sheath was provided for the scabbard to protect it from the weather. The type of fur used was determined by the rank of the wearer, and deer, wild boar, or bear skins were commonly used for this purpose." (Quote from: The Shogun Age Exhibition, cat. entry #19, p. 52)

The images to the left and below are from a detail of a print by Yoshitoshi from his "100 Aspects of the Moon".

|

||

|

Shishi |

獅子

しし |

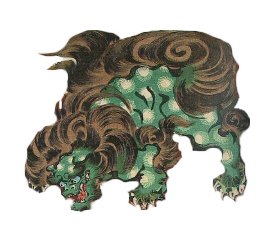

Lion: "According to Buddhist tradition, the shishi was a lionlike (though still essentially imaginary) beast that was a disciple of the Buddha, and it was shown in pictures reclining at the Buddha's feet or else supporting the seated Buddha. Consequently the phrase 'Lion Throne' (Shishi no Za)... The shishi also came to be associated with the deity Monju (Sanskrit Monjushri), the bodhisattva of wisdom and intellect, and is most commonly shown supporting this deity on one side of the Buddha while a white elephant supports the bodhisattva Fugen (Sanskrit Samantabhadra) on the other." (Quoted from: Kabuki Plays on Stage: Restoration and Reform, 1872-1905, p. 42)

Rebecca Salter in her Japanese Popular Prints: From Votive Slips to Playing Cards (p. 122) says: "From the animal kingdom an imaginary beast known for his skill at exorcism, shishi (lion) was recruited. A lion dance with a fierce shishi head worn by the dancer was used to drive out demons and likewise a look from the shishi was considered enough to drive the smallpox kami away." |

||

|

Shishimai |

獅子舞

ししまい |

Lion dance.

This lonely little, but festive lion dancer image to the left is a detail from a larger surimono. Although it is signed the signature is as yet unread. It has been sent to us by E., one of our favorite correspondents and a great and generous contributor to this web site. Thanks E! |

||

|

Shishi no za |

師子座 ししのざ |

Buddha's throne: "Shishi no za, a buddha's seat, so called because a buddha among men is like a lion among beasts." (Quote from: Tale of Flowering Fortunes : Annals of Japanese Aristocratic Life in the Heian Period by the McCulloughs, p. 622) There are a number of similar alternatives for the throne of Buddha which could be used.

Haile Selassie, the emperor of Ethiopia, was known as the Lion of Judah, King of the Jews because of his ostensible descent from the House of Solomon. For that reason the lion was seen on his crest and on his national flag. |

||

|

Shishō |

四生 ししよう |

The Four Types of Beings of the Buddhist canon: born of a womb, of an egg, of moisture like insect, and spontaneously from nothing due to their karma. |

||

|

Shishu no zōjigoku |

四種の増地獄 |

The Four Additional Hells |

||

|

Shitadashi Sanbasō |

舌出三番叟

しただしさんばんそう |

Sanbasō with His Tongue Stuck Out: This is both the name of this motif and the name of a play written by Sakurada Jisuke II (桜田治助: 1734-1806). Nakamura Nakazō I (中村仲蔵: 1736-90), a famous dancer-actor, was known for his tongue-sticking-out performances. As Sanbasō he used this technique. "It is said that Nakazō imitated a traditional child's toy, modeled after a humorous character's head whose tongue sticks out when a string is pulled. When Sanbasō, absorbed in the joy of his dance, sticks out his tongue, it greatly enhances his comic charm. This tongue-sticking-out business also became an important part of Nakazō's villain roles, where the tongue is painted bright red for emphasis. Sekibei in The Barrier Gate... provides an example. Sticking out the tongue may also incorporate a spell to ward off evil spirits." Quoted from: Kabuki Plays on Stage: Darkness and Desire, 1804-1864, p. 53.

The above detail comes from a robe worn by a female figure in a print by Toyokuni III from the late 1840s. |

||

|

|

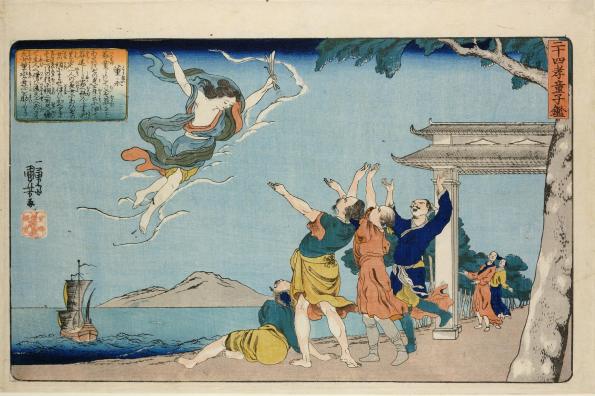

下絵

したえ |

A rough sketch -

The image to the left is from the collection of the British Museum. Their curatorial files note: "First-stage preparatory drawing for woodblock print (shita-e). Toei bidding farewell to Heavenly Weaver; Chinese-style gate and Western sailing ship in background; rider on horseback on verso; with pentimenti. Ink on paper."

The image shown above, also from the collection of the British Museum, is a fine example for comparison between the initial thoughts for this print and the finished product. |

||

|

Shita-etsuke |

下絵付け したえつけ |

"For underglaze painting (shita-etsuke), cobalt and iron compounds are most commonly used almost exclusively." |

||

|

Shita-uri |

した売 |

There has been a bit of confusion about the meaning of this seal. Some sources say it means "under the counter". Others say it means "restricted".

Richard Lane gives a completely different reading and interpretation in his Hokusai: Life and Work. In it he describes a print of Tsutaya's retail operation: "On a shelf toward the rear are displayed newly published prints and books (the prints seen stacked on the front mats are the so-called shita-uri, 'floor-sales', consisting of lower quality items and outdated actor prints)." [We do not agree with Lane on this assessment of prints which appear with this seal.]

Christie's auction house translated this term as 'limited edition'. We feel that this is probably the more appropriate use.

The seal seen to the left is a detail from the Toyokuni III print shown below.

|

||

|

Shizuki Tadao |

志筑忠雄 しづき.ただお |

Shizuki Tadao (1760-1806) is the man who coined the phrase 'sakoku' to describe Japan's self-imposed isolation.

Communications between groups of Japanese intellectuals located in different cities were difficult during the 18th c. "Some time in the 1780s the Nagasaki interpreter, Shizuki Tadao (1758-1806), wrote Ōtsuki Gentaku that a servant of his had just just been conscripted as coolie for a daimyo procession to Edo, and so he was taking advantage of this to write to ask him for 'any book you have there that describes stimulating and interesting theories of physics or astronomy, whether in Chinese or a Western language. I would particularly like to see a mathematics book on logarithms you said you were writing...' " Quoted from: Rangaku and Westernization by Marius Jansen in Modern Asian Studies, 18, 4 (1984), p. 544. |

||

|

Shōbu |

菖蒲

しょうぶ |