JAPANESE PRINTS

A MILLION QUESTIONS

TWO MILLION MYSTERIES

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

Ihai thru Izumiya |

|

|

|

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

|

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA諡 |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers or highlighted words to go to linked pages. |

|

Ihai |

位牌

いはい |

A Buddhist mortuary or memorial tablet. The ihai is said "...to provide the spirit a place to dwell."

"...the Buddhist god shelf, universal in all houses except the very poor or makeshift ones, on which the memorial tablets (ihai) of the family's dead are kept." (Quote from: The Great Loochoo: A Study of Okinawan Village Life by Clarence J. Glacken, p. 65)

"On New Year's day... the Japanese must rise, and after washing and arraying himself in festal attire, salute the rising sun, then offer thanks to the gods of heaven and earth, and bow himself down before the ihai (tablets) of his ancestors at the household altar, and not till then turn his attention to the living." (Quoted from: Japan: Travel and Researches by J. J. Rein, 1884, p. 438)

Another wooden Buddhist (grave) tablet is the sotoba (卒都婆).

From Lafcadio Hearn's Glimpses of an Unfamiliar Japan, Vol. 2: "There are differences, however, of size; and the ihai of a man is larger than that of a woman, and has a headpiece also, which the tablet of the female has not; while a child's ihai is very small."

"This ihai is simply the constituting element in the family altar, its sine-qua-non. One more significant item which may be kept in the butsudan is the «book of the past», the kachoko, where the death-days of all the dead who are to be taken care of (at the actual altar) are entered." (Quoted from: Grave and Gospel by Jan-Martin Berentsen, p. 30)

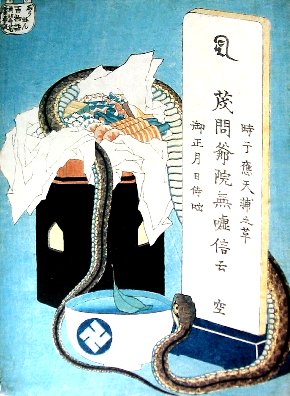

To the left is a Hokusai print showing a snake slithering around an ihai. |

|

Religion and Societies: Asia and the Middle East Carlo Caldarola wrote (p. 632): "Funeral ceremonies and ancestors' death anniversary rites are performed by a priest of the family temple, either in the temple itself or in front of the family altar. In some sects, a portion of the funerary ashes is deposited at the family temple. In other, an ihai, a duplicate of that in the family butsudan, is also left at the family temple. Whereas Shinto shrine affiliation is prescribed by residence, Buddhist temple affiliation depends mainly on kinship ties, and thus most persons belong to the same temple as their parents. [¶] "Household rites are performed primarily to benefit the spirits of the dead. Japanese Buddhists hold that the spirits (reikon, tamashii) of the dead do not become 'happy spirits' (hotoke) until the forty-ninth day after death, at which time they stop wandering around the house and leave for the grave. Hence some families keep the deceased's ashes in the house until that day. During that time a new ancestral tablet, sometimes with a photograph of the deceased, is placed upon a low table under the family altar. Incense sticks are burned continuously, and fresh water or tea, and rice, are offered daily. After the forty-ninth day, the hotoke becomes one with the family ancestral group, except on special occasions.... Theoretically, anniversary rites for individual ancestors should be performed for 50 years after the date of their demise..."

In an appendix to an 1880 translation of the 'Chiushingura' is a section on ihai: "These tablets are inscribed with the posthumous name (okuri-na) [諡] of the deceased and date of his death. When the wife survives the husband , she often has her name added in red letters, which upon her death are converted into black ones." (Chiushingura: or, The LoyalLeague : a Japanese Romance, pp. 178-9) From the same translation is a wonderful passage: "Yuranosuke, drawing from his bosom the ihai of his dead master, placed it reverently on a small stand at the upper end of the room, and then set the head of Moronaho, cleansed from blood, on another opposite to it. He next took a perfume from within his helmet, and burnt it before the tablet of his lord, prostrating himself and withdrawing slowly, while he bowed his head reverently three times, and then again thrice three times. [¶] 'O thou soul of my liege lord, with awe doth thy vassal approach thy mighty presence, who art now like unto him that was born of the lotus-flower to attain a glory and eminence beyond the understanding of men! Before the sacred tablet tremblingly set I the head of thine enemy, severed from his corpse by the sword thou deignedst to bestow upon thy servant in the hour of thy last agony.' " (Ibid., p. 142) And then Yuranosuke burst into tears.

And what about the pets? That was dealt with in 1904 in the 5th edition of The New Far East by Arthur Diósy (p. 105): "We shall find the modern Japanese described as a gentle creature, so full of the milk of human kindness that he will pay for Buddhist prayers to be said for the soul of his dead dog, or cat, or ox, and cheerfully disburse thirty Sen for the decent burial, in the grounds of a temple, with a short service, of his lamented fourfooted friend, occasionally even a larger sum, so that poor doggie, or puss, may have a mortuary tablet, or ihai, to keep its memory green."

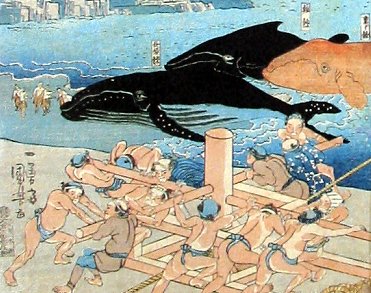

And tehn there were whales: "Important rituals are performed at Buddhist temples after the [whaling] season. To prevent a killed whale turning into a 'hungry ghost' (gaki) that may cause accidents and disease, it may receive a funeral similar to a human being's. The whate is give a posthumous name (kaimyō) that is inscribed on a memorial tablet (ihai) and registered in the death registry (kakochō) of a Buddhist temple. Moreover, memorial rites (kuyō) are held where temple priests recite from the sacred osegakikyō sutra, which is also recited for human beings lost at sea... At least twenty-five memorials and festivals (matsuri) are held every year in Japan to honour killed whales. Tombs and memorial stones for whales exist in forty-eight locations... A tomb in Kōganji (a temple dedicated to whales in Yamaguchi prefecture) marks the burial site of whale foetuses and has been declared a national historical monument. Towards the end of April, several temple priests read sutras for several days and nights to help the whales be reborn in a higher existence." (Quoted from: Unveiling the Whale: Discourses on Whales and Whales by Arne Kalland, p. 156)

Above is a detail from a Kuniyoshi print of fisherman hauling in dead whales.

In Japan and Her People, Volume 2 published in 1904 Anna C. Hartshorne tells the story of a beautiful young girl who is engaged to marry a samurai. They are very much in love. However, he has to go away to fight and while gone she dies. Her parents place an ihai at her 'grave'. They then set out on a religious pilgrimage. While they are gone the young samurai returns and hearing that the girl is dead decides to kill himself. But, just as he is about to act, he hears her lovely voice tell him that she has not gone and they get married and she bears him a son. When her parents return they hear that the samurai had married and when they see him they scold him for being so fickle. When he insists he has not been, but has, in fact, married their daughter he insists that they look inside the house for themselves. There on the bed is indeed their baby grandson and lying next to him is the ihai.

Whereas social standing was not meant to be a part of a Buddhist funeral there were subtle clues separating individuals and this had to do with the posthumous name placed on the ihai. "More important than the sheer numbers of funeral services is the fact that so many of them were performed for people confined to low levels of social status. Funeral sermons usually avoid mentioning social ranks, but they can be inferred from references to the laypersons' Buddhist ordination titles, which reflected the rigid hierarchical distinctions of Japanese society. Analysis of Buddhist titles in Sōtō funeral sermons reveals the relative social standing of the audience for each. These titles often appear in conjunction with stereotyped words of praise for the deceased reveal his or her occupation. Analysis of titles used in medieval Sōtō goroku [literally 'recorded sayings' written in Chinese] confirm that only a small percentage of the funeral sermons recorded were delivered for members of the clergy." (Quoted from: Sōtō Zen in Medieval Japan by William Bodiford, p. 199) Now for footnote 65 on page 279 which is real eye-opener: "The starting point for this type of analysis is... a sixteenth-century guide to rituals used at rural Rinzai temples. This text explains in detail the proper titles to be used on mortuary tablets (ihai). More than thirty different titles are used for every type of person, from an emperor, to a yamabushi, to a blind man..."

Ancestor Worship in Contemporary Japan by Robert John Smith wrote in 1974 (p. 79) that "The origin of memorial tablets (ihai) in Japan is uncertain. They take many forms, varying by period, region, and sect of Buddhism. Two possibilities for their origin is suggested...: one is that they are Confucian, deriving from the wooden tablets on which the Chinese write the names and ranks of generations of ascendants...; the other, which seems far less likely, is that they may be related to the shaku, the flat tablet through which the Shinto gods descend from heaven." Smith noted that this points at the nearly ubiquitous division between the 'continentalists' and the 'nativists'. ¶ "Memorial tablets appear to date from the Kamakura period when Buddhist funerals were becoming common..." Smith adds that it is difficult to determine the age of an ihai even when a date is included because tablets which are destroyed or lost in floods or fires "...will often be remade. But I did see many from the nineteenth century and earlier, primarily in rural areas, that are three or four times the size of the standard tablets of today and made of unlacquered wood with the inscription in india ink rather than carved into the surface and filled with gold."

"Nichiren Shōshū believers do not enshrine ihai in the family altar."

Lafcadion Hearn is one of those who believed that the ihai came to Japan via Chinese Confucianism. |

||

|

|

||

|

Ihara Saikaku |

井原西鶴 いはらさいかく |

One of the most influential novelist in Japanese literature, especially during the Edo period. He helped to establish a most libidinous genre during the age of ukiyo-e. Saikaku lived from 1642-93. Recently we found a reference to one of his tales in which men sail off to an island of women. We are quoting it here because it goes a long way toward making the point of how outrageous his work could be. |

|

"Saikaku’s Kōshoku ichidai otoko 好色一代男 of 1682, published in the same Genroku era as Ryūsen’s maps, celebrates the Island of Women as the final frontier of sex tourism. The libidinal adventures of Yonosuke conclude with the hedonistic hero building a boat on Penis Island and, with seven of his like-minded friends, setting sail from Izu for the Island of Women. Knowing that it would be a destination from which “they weren’t ever going to return,” they left Japan fully equipped with “250 pairs of metal masturbation balls, … 600 latticed penis attachments, 2,550 water-buffalo-horn dildos, 3,500 tin dildos, 800 leather dildos, 200 erotic prints, … and 900 bales of tissue paper” (Ihara 2002 [1682], 56)." Quoted from: Demonology and Eroticism: Islands of Women in the Japanese Buddhist Imagination by D. Max Moerman, Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 36/2, Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture, 2009, p. 370. |

||

|

|

||

|

Ikari |

錨

いかり |

An anchor. There are multiple variations on the anchor for different family crests or mons. The image to the left below is a detail from a Yoshiiku triptych showing one small area of a robe of a courtesan decorated with an anchor.

|

|

John W. Dower said that the anchor stood for "steadfastness and staying power". Maude Rex Allen in 1917 said it was safety and hope. A publication from 1894 gave ikari as safety only.

The ikari-sō (錨草) or Epimedium grandiflorum var. thunbergianum got its name because it looked so much like the traditional Japanese anchor. The sō (草) part means 'grass', but not in the way we refer to grass. We do not know how long this plant has had this particular name. The image below is shown courtesy of Shu Suehiro at http://www.botanic.jp/plants-aa/ikaris.htm. It is listed in Chado, The Way of Tea: A Japanese Tea Master's Almanac by Sasaki Sanmi as one of the flower/plants which can accompany the tea ceremony.

The ikari is one of the 20 precious items associated with the 7 Propitious Gods. See our entry on the takaramono to see the other 19.

Lafcadio Hearn in his Romance of the Milky Way and Other Studies and Stories from 1905 quotes a poem about the "ship-following ghost": "That Shape, carrying that anchor on its back, and following after the ship - now at the bow and now at the stern - ah, the ghost of Tomomori."

Louis Frédéric in the Japan Encyclopedia (p. 375) writes: "Ikari kazuki. Title of a Noh play: an old boatman and the spirit of Tomomori tells a wandering Buddhist monk about the deaths of the child-emperor Antoku and the warrior Tomomori, who drowned himself during the Dan no Ura by holding an anchor in his arms."

"The Heike's account of the death agonies of the Taira at Dannoura is one of the most poignant and tragic scenes in Japanese literature. Kiyomori's widow, embracing her grandson, the child emperor Antoku, and carrying also the jewels and sword of the sacred regalia leaps into the sea (the jewels are retrieved, but the sword is lost); Lady Kenreimon'in, Antoku's mother, also plunges into the sea, but is fished out by the Minamoto. Many Taira warriors, including Tomomori, commit suicide by drowning. Donning additional armor and holding or shouldering anchors to ensure that they sink to the bottom, they leap into the sea one after another. In several cases, they go to their deaths holding hands. Thus Tomomori and his foster brother Ienaga, having earlier vowed to die together, plunge hand-in-hand into the waves." (Quote from: Warriors of Japan as Portrayed in the War Tales by Paul Varley, pp. 145-6)

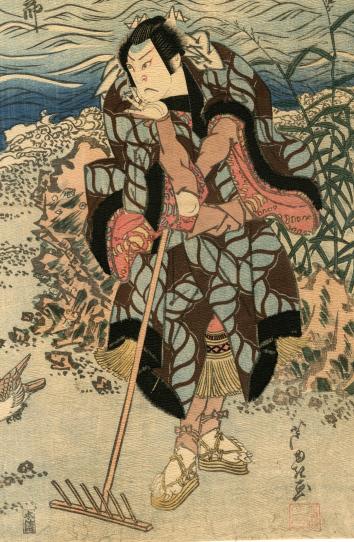

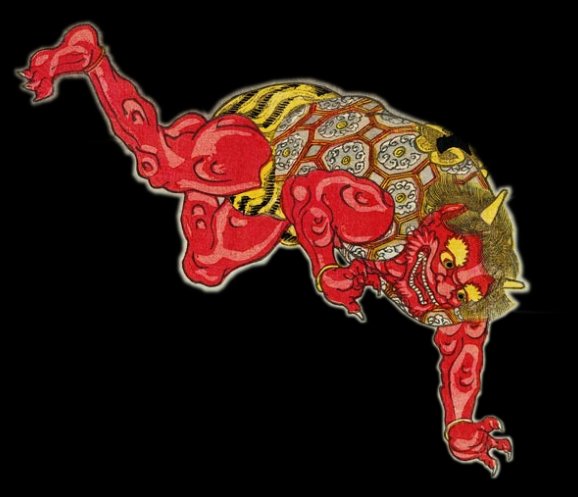

Above is an image by Kuniyoshi of the ghost of the drowned Tomomori with his ikari.

Looking for physical evidence of the attempted Mongol invasion of Japan in 1274: "In 1994 archeologists discovered three wood and stone anchors at Kozaki harbor, a small cove on the southern coast of the island of Takashima. The largest anchor was still stuck into the seabed with its rope cable stretching toward the shore, and providing a tantalizing clue that a wreck lay nearby." (Source and quote from: The Samurai Swordsman: Master of War by Stephen Turnbull, p. 39)

"Forced by the Japanese raids to stay in their ships, and unable to drop anchor in protected harbor waters, the Mongol fleet was obliterated." (Ibid., p. 41) |

||

|

Ikarizuna |

碇綱

いかりずな |

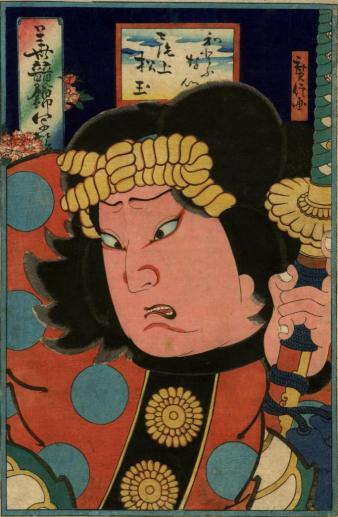

Anchor rope - The images to the left and below represent Watōnai, a popular character in kabuki play. His robe is often decorated with an ikarizuna and he often wears part of one as a headband. Both are from the Lyon Collection. The image to the left is by Hironobu from 1865.

Detail of an Ashiyuki diptych from 1824. |

|

Ikiryō |

生霊 いきりょう |

Jim Breen's web site defines this term as a "vengeful spirit (spawned from a person's hate)".

"Michizane transformed into a troubled spirit after his death, but similar transmogrifications might occur even while the human in question was alive, the most notorious case being that of the living spirit (ikiryō) of Lady Rokujō in Murasaki Shikibu's Genji monogatari (The Tale of Genji; early eleventh century). In a series of disturbing episodes, the spirit of the still-very-much-alive Rokujō detaches itself from her body to haunt and torment her rivals — all unbeknownst to her. Even to the "changing thing" itself, corporeal appearance is deceptive; present in one place, she is also present elsewhere, simultaneously self and other, her form betraying a dangerous instability guided by an intensity of emotion beyond her control." Quoted from: Pandemonium and Parade: Japanese Monsters and the Culture of Yokai by Michael Dylan Foster, p. 6. |

|

Lady Rokujō is so jealous of Genji's new lover that her spirit leaves her body and causes the young woman's death. In the Noh play Aoi no Ue Rokujō's carriage is forced to let the carriage of Lady Aoi, Genji's latest lover, pass by. "When Lady Rokujo's demonic spirit threatens Lady Aoi, a Buddhist monk is summoned. He battles the demon, using prayers against the staff of the demon, and ultimately drives her out. The play fiddles with the original by having Lady Aoi survive her encounter with the demon. Otherwise, it's a straightforward cautionary Buddhist story, with Lady Rokujo lamenting the fleeting nature of happiness on earth (and, with a roving-eyed boyfriend like Genji, she's easy to agree with), and using Buddhist prayers to save Lady Aoi's life."

Philip Gabriel in his Spirit Matters: The Transcendent in Modern Japanese Literature from 2006 (pp. 122-123) notes that the ikiryō plays a role even in the works by our contemporary Haruki Murakami. It is hinted at in Kafka on the Shore. After a particular incident Kafka, the young protagonist, asks: "What triggers people to become living spirits? Is it always something negative?"

"In a thorough study of Heian literature Fujimoto Katsuyoshi has found no precedent for possession by living spirits (ikisudama; ikiryō) in extant monogatari; there are merely scattered references to ikiryō in chronicles and brief narratives (setsuwa). According to Fujimoto, the full-blown phenomenon of mono no ke as a living rather than as a dead spirit (shiryō) is Murasaki Shikibu's invention, replacing the traditional quarrel between a new wife and the spirit of her deceased predecessor. Fujimoto argues that Murasaki Shikibu's innovation requires us to focus on the possessor ('tsuku ningen ni shoten o ate'). ¶ Excitement over Murasaki Shikibu's originality in emphasizing Rokujō's role as living possessing spirit can become a distraction. It can draw readers and critics so deeply into the psychology of the ikiryō that the possessed person is all but forgotten. If that happens, the reader has ironically repeated the neglect that motivated Aoi to seize the woman's weapon of spirit possession. By becoming possessed, Aoi hopes to be seen and heard and no longer neglected by Genji. It is understandable that Genji, feeling the need to defend himself against charges of neglect, fixes his attention on Rokujō's jealous possessing spirit, but it would be a mistake for us to do the same. If we look at the possession solely through Genji's eyes, we will fail to understand Aoi's strategy. In the Aoi case, Murasaki Shikibu shows us the possessed person and the possessing spirit as parties of equal weight operating within the same phenomenological framework, a shared reality. It is therefore important to refrain from demonizing this exceptional ikiryō as if it were merely another vengeful shiryō." Quoted from: A Woman's Weapon: Spirit Possession in The Tale of Genji by Doris G. Bargen, pp. 86-87. |

||

|

|

||

|

Ikkyū |

一休

いっきゅう |

Zen priest - poet and thinker (1394-1481) One of the noted abbots of Daitoku-ji. 1

"Growing up in Ankoku-ji, one of the ten secondary temples (Jissatsu) of the Five Mountains (Gozan) Zen monasteries, Ikkyū earned renown for both his talents in composing kanshi (poems written in Chinese) and his serious pursuit of the truth of Zen when he was still a teenager. Increasingly dissatisfied with the corruption of the Gozan monasteries, Ikkyū fled Ankoku-ji to study under Ken'ō, an eccentric monk who had refused his own seal of transmission, the document certifying a Buddhist priest's enlightenment. From the time when he was a young disciple of Ken'ō until he died as the abbot of Daitoku-ji temple in 1481, Ikkyū was an extremely serious priest who fiercely attacked anyone who was lacking in sincere Zen spirit. At the same time, he was also an eccentric monk who frequented brothels and bars, an unusual kanshi poet whose versus juxtaposed transcendental Zen experience with explicit descriptions of sexual love." (Quoted from: Basho And The Dao: The Zhuangzi And The Transformation Of Haikai, by Peipei Qui, pp. 102-3)

Donald Keene makes the point in his Some Japanese Portraits that the first person in all of Japanese history of whom a true biographical sketch can be written in a Western sense is Matsuo Bashō (松尾芭蕉: 1644-94). One of the reasons is the material he left behind plus that written about him by students and friends. Other than that most biographical material lacked substance partially because "...individuality was not a quality emphasized by the Japanese of feudal times. Even in portraiture it is almost impossible between faces..." (Keene, p. 17-18) Sometimes differences in gender are difficult to make out. See, for example, the works of Harunobu where you can't always tell if it is a young man or young woman you are looking at. Even Utamaro makes it difficult at times. ¶ "Something resembling individuality did, however, exist in Japan, the tradition of eccentricity. In a feudal society where conformity was demanded of its members, people tended to behave in a manner appropriate to their age, occupation, and status in society without much display of strong individuality.... But the eighteenth century was also a golden age for eccentric, and their antics were indulgently observed and reported by chroniclers." Note the image to the left which ostensibly shows Ikkyū passing gas in the most glaring way as though he was a modern American teenage boy or frat member. |

|

As the story goes Ikkyū was born the son of an emperor on New Year's Day in 1394. This may or may not be true, but "But there is evidence in [his] poetry that he believed himself to be of imperial stock, and he often visited the palace to see the emperor. When Go-Komatsu was dying in 1433, Ikkyū was summoned to his bedside." However, he was not raised as a prince because he mother had been banished from the court before his birth. Yet, before she died she wrote to him and extolled him to be such a great priest that even the Buddha and his minions would look up to him. (Ibid., p. 19) ¶ At 5 he was sent to study for the priesthood. Clearly he was precocious and extremely pious. He accomplished things in his youth expected only of the most scholarly and adept adult priests. When his teacher Ken'ō (謙翁) died in 1414 Ikkyū was despondent and "...spent a week in meditation by the shores of Lake Biwa before finally deciding to commit suicide by throwing himself into the lake. He was saved by a man sent by his mother who, knowing of his despondency, had feared he might turn to self-destruction." (Ibid.) ¶ After he gave up suicide as a viable option he went to see if he could become a pupil of the stern disciplinarian Zen master, Kasō Sōdon (華叟宗曇: 1351-1428). Kasō refused to see him but Ikkyū persisted. One day when the master was going out he saw Ikkyū standing by the gate. Kasō ordered his assistant to throw water on him. When he returned Ikkyū was still waiting so Kasō accepted him as a pupil. In 1418 Kasō gave Ikkyū his name which means 'a pause'.

At the age of 26 he attained enlightenment. Sitting in a boat on Lake Biwa while meditating he heard a crow's cry and "...he cried out in wonder. He felt that all his uncertainties had been purged away. When he told Kasō what had happened, the latter said merely, 'You have attained the status of an arhat. You are still not a man of supreme accomplishment.' Ikkyū replies, 'If that is the case, I am delighted to be an arhat and have no desire to be a man of supreme accomplishment.' Kasō responded, 'You are truly a man of supreme accomplishment.' " ¶ In 1422 at a ceremony at the Daitoku-ji everyone all of the priests showed up wearing fine robes - except Ikkyū who was dressed very shabbily. When asked why he chided the other monks as being false and said "I alone ornament this assembly." Afterwards Kasō was asked if he had selected his successor and he said he had: "Ikkyū, though at times he acts like a madman." (Ibid., p. 21)

"Ikkyū's 'madness' was the expression of unending rage over the stupidity and corruption of the priesthood. He took for his sobriquet the name Kyōun, 'crazy cloud,' and the character kyō, 'crazy,' is sprinkled throughout his poetry. In his revolt against the hypocrisy of other priests, who pretended to lead the lives of saints, he went to the opposite extreme." (Ibid.) He rejected the idea that a Buddhist priest should not eat fish, drink saké or indulge in sexual intercourse. He even wrote a poem called The Brothel quoted by Keene on page 22:

To lie with a beautiful woman - what a deep river of love! Upstairs in the brothel a whore and an old Zen priest are singing. I derive such pleasure from her embraces and kisses I've never once thought of renouncing the flames of passion.

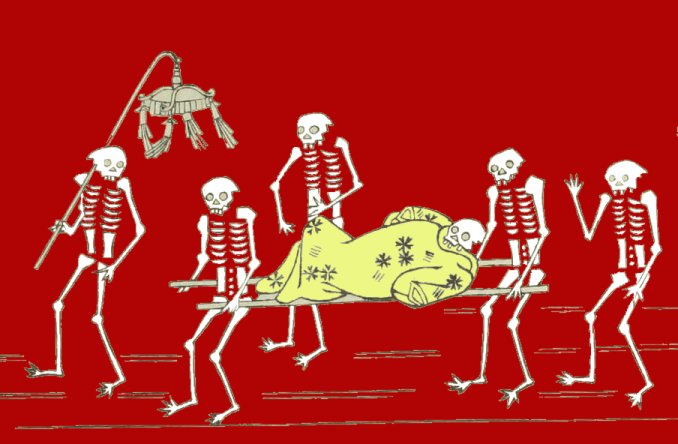

Ikkyū seems to have saved his most severe attacks for those on the 39th abbot of the Daitoku-ji, Yōsō (1376-1458). The temple had burned down and Yōsō had set about rebuilding it. He got lots of financial support from well-to-do laymen. However, Ikkyū thought that money was also raised from others by offering salvation and so he called Yōsō "...a poisonous snake, a seducer and a leper..." which he was in fact. [Here Ikkyū plays a role similar to that of Luther and other protestants who were enraged by the sale of indulgences by the Catholic church in Europe in the 16th century.] After Yōsō died Ikkyū was hardly less sparing of his successor, Shumpo (1410-96). These "...attacks so enraged Shumpo's followers that in 1457 an attempt was made on his life." Keene says: "Ikkyū's attacks on Yōsō were intemperate and probably unfair, but they reveal his uncompromising insistence on maintaining the spirit of Zen." However, Ikkyū was equally harsh on himself and said that his sins would "...fill the universe" and that also he "may... serve in perpetuity as a master of hell." (Ibid. p. 23) ¶ At 76 he fell in love with a blind woman named Mori. "Despite his love for Mori and other women (and also boys), Ikkyū remained convinced that human beings were no more than skeletons clothed in flesh. His curious work Gaikotsu (Skeletons), written in 1457, described under the guise of a dream about skeletons his belief that the beauty and glory of this world are illusions." ¶ In Skeletons Ikkyū describes a scene of skeleton pall-bearer carrying the skeleton of another one in a funeral procession. Draped over the corpse is an elaborate robe. Nearby in the original volume is a poem questioning such lavish behavior when in the end all comes to naught anyway. Below is an illustration of that scene with my coloring and sans text:

In 1886 Yoshitoshi published a diptych of an encounter between Ikkyū and the Hell Maiden. That is a skull the priest is carrying atop the end of a pole. It seems to mock the umbrella carried by one of her attendants. "The subject derives from a story associated with the medieval-era Rinzai Zen priest Ikkyū, who was legendary for his fondness for engaging both Buddhist devotees and cynics, including a courtesan nicknamed Jigoku Dayu, in lively dialogues on Buddhist philosophy." (Quoted from: Faith and Power in Japanese Buddhist Art, 1600-2005 by Patricia Graham, p. 211)

|

||

|

|

||

|

Ikō |

衣桁

いこう |

Clothes rack or clotheshorse: "The iko (clothes rack) was used for displaying fine clothing in a room. This kind of iko was not collapsible and was used to show the design on the clothing (kimono) in full. Small iko that could be folded were used temporarily in sleeping rooms..." Quoted from: Songs from a Bamboo Village.

Both images come from the Lyon Collection. |

|

Imina |

諱 いみな |

Real or posthumous name according to some sources. However, Mark L. Blum in his The Origins and Development of Pure Land Buddhism: A Study and Translation of Gyōnen's Jōdo Hōmon Genrushō (page xviii) gives a more complex and nuanced interpretation. "The term imina 諱 (忌名) is supposed to be the actual name of someone as referred to by posterity, but its usage is problematic in that it may indicate a given lay name (Sadakane 定兼 is the imina for Shinkū 眞空) or it may designate a commonly used monastic name (Genkū 源空 is the imina for Hōnen.) Originally the imina was contrasted with the eulogistic, posthumous denominative okurina 諡 (贈名), but in this period these two signifiers were often not distinguished, with the result that the character 諡 could also be read imina." |

|

Inazuma |

稲妻

いなずま |

A flash of lightning. Often used as a mon or crest in any one of a number of diverse variations. The kanji can also be vocalized as 'inaduma'. 1

There is a novel from 1807 by Santō Kyōden, Mukashi banashi inazuma hyoshi (An Old Time Lightning Bolt Tale) in which the two major antagonists wear kimonos which identify them iconographically. Fuwa Banzaemon carries a sword called 'Thunder' and wears robes with a lightning and cloud motif. His opponent Nagoya Sanzaburō's sword is the 'Amorous Swallows' and his robe is decorated with the 'swallows-in-the-rain' motif. The image shown below is a large detail from a diptych by Kunisada from 1816 in the Lyon Collection.

|

|

Inden |

印伝

いんでん |

Lacquered deerskin or shikagawa (鹿皮). It was a technique first used on armor and later for such items as purses or tobacco pouches.

Preparation: The deerskin is a applied to a revolving drum over a smoky straw fire. Handmade paper stencils, katagami, are used to apply a pattern which is lacquered later. At the end, the individual pieces are cut and sewn together.

In a May 20, 2010 article in the Japan Times by Alice Gordenker it says there are two ways of applying the patterns to the deerskin. In the first the skin is dyed "black, brown, red or navy blue. Then, using stencils cut from Japanese paper, they apply natural lacquer [the urushi-tsuk or 漆付け method] to create durable designs in both traditional and modern patterns." In the second "the fusube [燻べ] method, which is actually much older, it's smoke that creates the patterns. Artisans tie deerskin around a rotating cylinder, secure paper patterns on the leather and turn the entire affair over a fire. The smoke darkens the exposed leather, creating patterns and leaving a smoky aroma that lingers even after many years of use."

The photo on the left of the deerskin purse with lacquered design of dragonflies or tombo was posted at Flickr by Eiko Eiko. The item shown above was posted at the same site by jin jing. |

|

Inga |

因果 いんが |

Karma, cause and effect: |

|

Ingaōhō |

因果応報 いんがおうほう |

Karmic retribution |

|

Ine |

稲

いね |

A rice plant motif. There is hardly anything which could have a greater significance to the Japanese. Staff of life, the measure of one's wealth, religious emblem - it covered it all in the most positive ways. The importance of the rice farmer in Japan even today should give one an indication of the overriding esteem in which the plant is held. |

|

Ingō |

院号 いんごう |

A posthumous Buddhist name. |

|

Innō |

陰嚢

いんのう |

Scrotum - the scrotum of the tanuki was often portrayed in an exaggerated manner. Add to that the comic nature of these images even when we don't know what the joke is. |

|

Inrō |

印籠

いんろう |

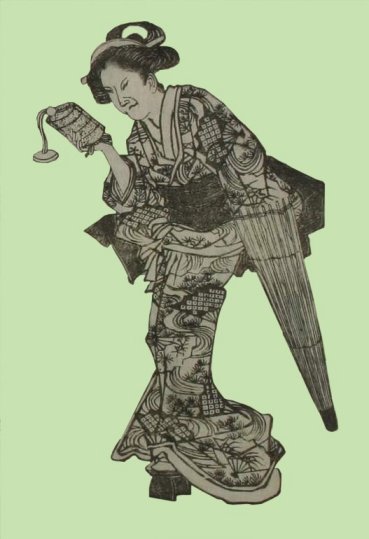

Inrō: Literally seal + basket. Isn't it odd that in the whole world of ukiyo prints inrō are hardly ever shown. In fact, the large image to the left from a book illustration by Toyokuni I dating from the early 19th century is the only one I can think of. Perhaps they show up in certain surimono, but in general they are almost non-existent. Of course, this is not the case in the real world. Inrō have been a hot-market item for the last fifty years or so. Anyone familiar with Japanese objets d'art knows what these are. ¶ Kimonos didn't have pockets and people needed a way to carry their medicines, inks for writing or cosmetics for beautification. There were pouches which could be carried, but the inrō were far less intrusive. ¶ However, originally they served a different function: As the kanji suggests they were used to carry one's personal seal and seal-paste so that their mark could be affixed to documents. "Their decoration encompasses in miniature virtually the entire range of lacquering styles and techniques current during the period. The rich variety of themes and styles among inrō reflects their importance as an emblem of the taste, status, and wealth of the owner. ¶ Inrō may have one or more compartments surmounted by a lid. The usual shape has a rectangular face and a flattened, elliptical cross-section, which hangs conveniently close to the body when suspended from the obi. Cord-channels run vertically through all the sections of an inrō, so that the sections are held in place by a silk cord threaded through all the sections. The ends of the cord are passed through a bead, then secured to a toggle, usually a miniature carving, known as a netsuke."

Quote from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan entry by Ann Yonemura (vol. 3, p. 313) |

|

Inuōmono |

犬追物 いぬおうもの |

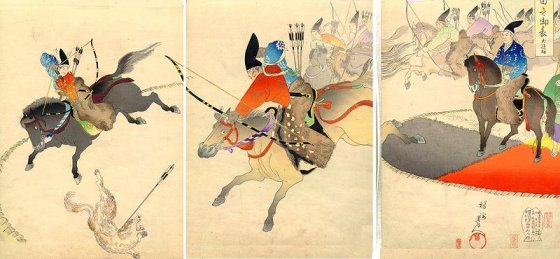

Dog-hunting sport: "Equestrian archery refers to the technique of shooting a bow from horseback. Equestrian archery dominated the battlefield only from the Heian period (794–1185) through the Kamakura period. Since this was so long ago, it is impossible to know what equestrian archery on the battlefield was actually like. In the past there was a sport called inuōmono (dog chasing), where archers on horseback chased dogs around a circular enclosure while shooting blunted arrows at them. Records indicate that this sport was practiced up until the beginning of the Meiji period, but today it is completely extinct. Since the line of transmission has been broken, just as with battlefield equestrian archery, it is nearly impossible to tell what inuōmono was like." Quoted from: Shots in the Dark: Japan, Zen, and the West by Shoji Yamada, p. 60

This triptych by Chikanobu was posted at commons.wikipedia. It dates from 1897.

"Practice in shooting at moving targets could be provided by shooting dogs, a speciality of the Hojo family that drew scorn from Toyotomi Hideyoshi in 1590 when he confronted them with firearms." Quoted from: Warriors of Medieval Japan by Stephen Turnbull, 49.

"Inu-oi-mono. 'Dog hunt,' sport practiced by samurai starting in the Kamakura period and consisting of shooting buttoned arrows at dogs. Within a large, roped-off circular area was another circle about 15 m in diameter in which dogs were released. Samurai on horseback galloped outside the larger circle, shooting at the dogs and trying to knock them over. This sport disappeared, along with the samurai class, in 1868. The game originated in China, where a popular Taoist divinity called Zhang Xian personified the art of archery (through confusion with the term zhanggong, 'archery' ), as he was represented holding hands with a child and hunting the heavenly dog with a bow and arrow." Quoted from: Japan Encyclopedia by Louis Frédéric, p. 392. |

|

Inzō |

印相

いんぞう |

The Buddhist mudra or sign made by the position of the hand or hands. "In Buddhist iconography every buddha is depicted with a characteristic gesture of the hands. Such gestures correspond to natural gestures (of teaching, protecting, and so on) and also to certain aspects of the Buddhist teaching or of the particular buddha depicted."

Quoted from: The Shambhala Dictionary of Buddhism and Zen, p. 148.

The examples to the left were provided by our generous contributor E. Thanks E!

The top example represents the abhaya mudra which is a gesture of fearlessness and granting protection. The bottom one is the varada mudra which stands for the granting of wishes.

There are several other mudras not shown here. For those of you who are interested I would suggest a search on Google or whatever else serves as your favorite search engine.

|

|

Iori |

庵

いおり |

A shelter or hermitage which often used as a stylized family mon or crest. Although this example includes a floral motif under the roof and between the beams of the shelter there are many other variations on this form. The floral motif need not be there. Nor does the shelter have to look exactly like this one.

The iori-mokko (庵木瓜) is a hermitage crest with a magnolia under the roof. The Fitzwilliam curatorial files note: "The motif alludes to Suketsune's hunting lodge at Susono below Mount Fuji, where he was finally murdered by the Soga brothers."

The image shown above by Kunisada is from the Lyon Collection. Whereas the iori motif is more often used to decorate the robes of Suketsune, but here appears on the robes of the Soga brothers. Click on it to see a much larger reproduction. |

|

Ireki |

入れ木

いれき |

A wood inlay or plug - often used to replace parts of woodblocks instead of carving whole new blocks. To the left is a print by Toyokuni III of Nakamura Utaemon IV in the role of Matsuemon. It dates from 1849. In 1862 Utaemon played that part again, but this time under his new name Shikan IV. So, a plug was carved, using the old woodblock. That print was by Yoshitora. The original 1849 image detail is on the left below while the Yoshitora detail is on the right.

Our choice of these example was inspired by an article by John Fiorillo in Andon 81. |

|

"It is generally quite difficult to determine whether an actor print is an ireki variation of the original design, unless we have impressions of both prints at hand. The reason is that the wood grain of the original block and the outline of the inserted plug are often not visible, as these parts are obscured by the pigments applied with the color blocks. Fortunately, when the original color blocks were used for the ireki edition, there were some cases in which the second head was smaller than the original, resulting in a visible white line or small unprinted area between the new head and the adjacent design elements." (Ibid.) |

||

|

|

||

|

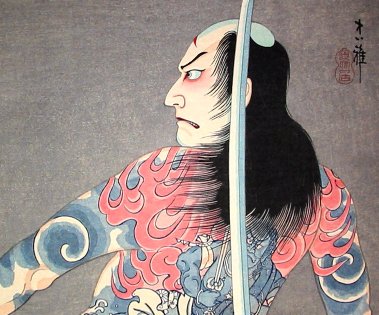

Irezumi |

刺青

いれずみ

|

A term for tattoo which is also called horimono. To the left (top) is a detail from a print by Tadamasa of Danshichi Kurobei from 1950. Below that is a larger detail showing Fudō Myōō.

|

|

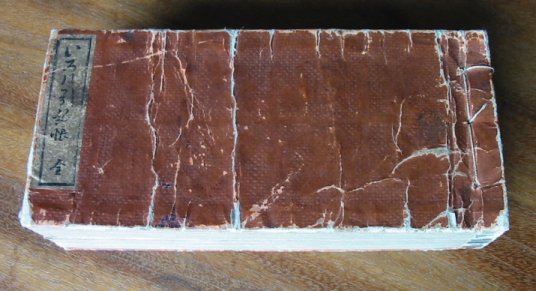

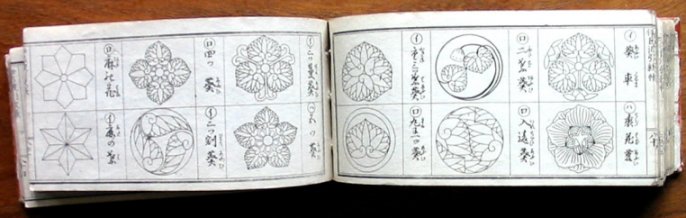

Irohabiki monchō |

いろはびき.もんちょう |

"Book of crests in the order of the iroha alphabet": Edited by Tanaka Kikuo, published by Matsuzaki Hanzō, Tokyo, 1881. Copper plate illustrations. 2 1/4" x 6 3/8". "These crests are arranged in the order of the Japanese kana syllabary, or alphabet, known as the 'iroha.'"

Source and quote from: Rain and Snow: The Umbrella in Japanese Art, by Julia Meech, published by Japan Society Inc., 1993, p. 119.

These crests were originally used by certain families, but "By the Edo period, however, even commoners, although they had no surnames, adopted emblems for their fancy clothing. Tradesmen took crests for trademarks and used them to decorate everything from toys to umbrellas. Kabuki actors and courtesans also aped the elite and often took more than one crest." Later Meech added: "There are between 4,000 and 5,000 design variations. During the the [sic] Edo and Meiji periods they were published in designers' catalogues know as monchō, usually in black and white." (Ibid.)

The Irohabiki monchō in the show at the Japan Society is from the collection of the Newark Public Library. |

|

Iroko |

色子 いろこ |

A kabuki actor who is also a male prostitute. |

|

Irozato |

色里 いろざと |

Red-light district. It is also referred to as iromachi (色町). |

|

Ishi |

石

いし |

Ishi is the Japanese word for stone. The image to the left is just one of many different variations on a popular choice of family crests. John Dower identifies these as paving stones. "Among the rigidly prescribed court costumes of prefeudal Japan, the check pattern was so esteemed that its use was restricted to courtiers who ranked higher than the third rank. The 'paving stone' motif reflects this esteem, rather than any particular significance attached to such stones themselves."

Quoted from: The Elements of Japanese Design p. 142. |

|

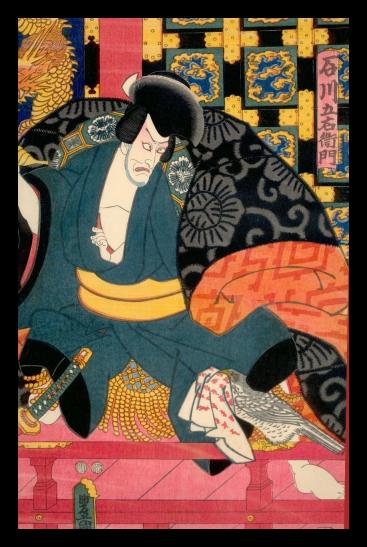

Ishikawa Goemon |

石川五右衛門

いしかわごうえもん |

|

|

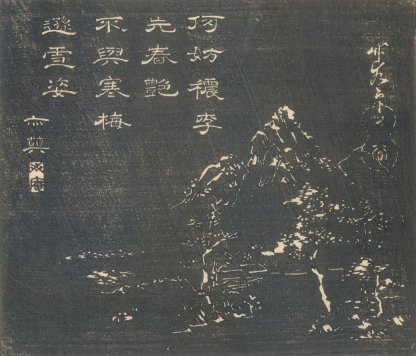

Ishizuri-e |

石摺絵 いしずりえ |

'Stone-printed picture(s)': Made in imitation of the ancient Chinese art of stone rubbings. "...in Japan, it was normally wood that was engraved and the more correct Japanese term is takuhon - a 'book of rubbings'." Quote from: The Art of the Japanese Book, by Jack Hillier, published by Sotheby's, vol. 1, 1987, p. 311.

To read more about 'stone-printed pictures' click on the image to the left.

Ishizuri can also be written as 石搨.

Michener in his Floating World (p. 76) said that Masanobu "...seems to have invented the use of gold dust, triptychs, pillar prints, mica grounds and ishizuri-e (stone-printed picture)." However, a little earlier Michener did note that "...some of his [i.e., Masanobu's] claims cannot be supported and many innovations attributed to him were probably the work of men less addicted to personal advertising."

Conrad Totman in Early Modern Japan (p. 393) added: "Successive generation of printmakers enriched the genre with other techniques. Besides developing color printing, Masanobu experimented with a technique called ishizuri, or 'stone rubbing,' in which a print's background was blackened and its lines appeared white. Some later print makers used this method, but it never gained wide popularity." |

|

板暈

いたぼかし

|

Ita-bokashi is a printing technique for creating soft edged, lineless gradations within an image. The block is chamfered by sanding down or cutting away the edge. Rebecca Salter notes that this method was often used for the folds of garments. This is commonly the case with shini-e or memorial prints among others, but clearly was also used for subtle gradations in areas other than that of fabrics. See the images to the left.

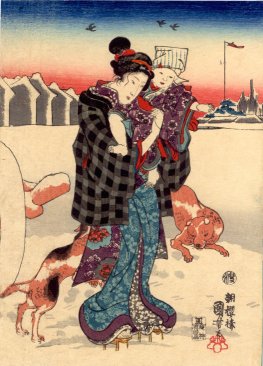

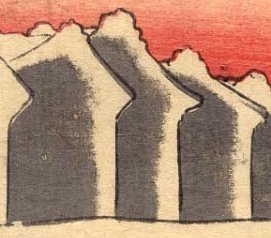

The image on top to the left is a Kuniyoshi chuban print - one of a triptych. It shows a woman holding a child standing in the snow while dogs frolic behind her. A close inspection of this print offers three distinct areas of ita-bokashi: the warehouses in the background; the reddish fur on the dogs; and the shading in the snow caused by the human and animal traffic.

This image was sent to us by my friend M. Thanks M!

Rebecca Salter in her Japanese Woodblock Printing (University of Hawai'i Press, 2001, p. 120) stated that ita-bokasi is "....gradation through chamfering the edge of the block. Often used to show folds in garments."

In Japanese Woodblock Printing by Hiroshi Yoshida (1939, p.4) lays out what he believed to be the salient features of color prints. In point 4 of 9 the author states: "Clarity is the life of wood-block printing. To be sure, there are methods known as ita-bokashi (where the block is cut down gradually in order to produce a soft edge in printing), in which clearness is sacrificed. This method is called into aid only when absolutely necessary, yet it still remains true that block printing is by nature essentially based on clear-cut blocks and clean printing." |

|

|

Itame-mokuhan |

板目木版

いためもくはん |

The printing of a wood grain within a print. A wood plank is soaked in water to open up the grain and is then inked and printed to intentionally reproduce the nature of the wood itself.

The images to the left are both details from a Toyokuni III print sent to us by our great contributor Eikei (英渓).

|

|

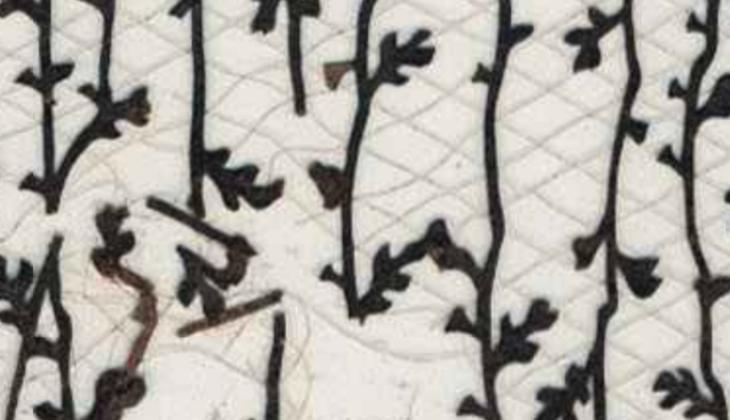

Itoire |

糸入れ

|

In the glossary of Carved

Paper: The Art of the Japanese Stencil from an exhibition at the Santa

Barbara Museum of Art in 1998 it states:

Method of reinforcing a stencil

by

The image to the left is a detail from a katagami owned by Mike Lyon. It shows the web of threads and in places it has been distorted or been broken due to use or because of some kind of accident. |

|

Itomaki |

糸巻

いとまき |

A card of thread motif from the late feudal era. Similar, but more elaborate designs shows spools of thread with each length indicated. However, here this motif is simplified to it barest minimum. In fact, it is so simple that if you didn't know what you were looking at you probably would not have a clue as to its true meaning.

While looking for more information on the term itomaki we ran across a curious entry. The Japanese for a manta ray is itomaki ei (糸巻鱝). Since our Japanese is not good enough to explain this we can only surmise that it has to do with the shape of this fish. It would be interesting to know when this term was first used. The photo shown below was posted at commons.wikimedia and originally comes from NOAA.

Sasaki Sanmi in Chado: The Way of Tea describes a particular cake called an ito-maki "...moulded in the shape of... a spool... in two different colours: red and white. It is also made of rakugan-ko and is used as a dry confectionery in association with Tanabata." |

|

Itsutsuginu |

五衣 いつつぎぬ |

"...literally - 'five silks', were women's undergarments in Heian times, belonging to the Imperial jūnihitoe dress." Quoted from: Ogyū Sorai's Discourse on Government (Seidan): An Annotated Translation by Olof G. Lidin, fn. 349, p. 182.

"Also, with regard to women's clothes, when making, for example, the 'five-fold silk dress' (itsutsuginu 五衣), the material, size and length should accord wtih the husband's or father's rank and stipend." Ibid.

Another term used for itsutsuginu is kasaneuchigi(襲内着?). Kasane 襲 literally means a 'combination of colors created by layering of garments' plus uchigi 内着 'everyday clothes' or 'underwear'. The Princeton Companion to Classical Japanese literature defines this term as a 'Five- (or more) layered robe'.

Ruth Shaver in her Kabuki Costume refers to kasaneuchigi as kasane uchiki. |

|

Iwai Hanshirō V |

岩井半四郎 いわい.はんしろう |

Kabuki actor who began his career under the name Iwai Tojaku. Ruth Shaver wrote: "Iwai Hanshirō V, an extremely 'pretty' actor, was the representative onnagata of the Bunka-Bunsei era. The public called him by the pet name of me-senryō or thousand-ryō eyes, for his eyes were remarkably beautiful and expressive. (Kawarasaki Gonjurō I was also called me-senryō.) Hanshirō was a skillful actor, showing his amazing versatility in a wide range of roles, from musume-gata (young women) to tachi-yaku (leading male characters). He established the role of the akuba (bad woman), and his stylization remains the kata for roles of wicked women.... The black costume worn by Gompachi originated with Hanshirō..." Quoted from: Kabuki Costume, pp. 83-84.

"Hanshirō was prolific in contriving fresh ideas for patterns. His Hanshirō kanoko (small-spot shibori or tie-dyeing resembling the spots on a fawn's hide) in the asanoha (hemp-leaf) pattern in blue and red was first used for the costume of Yaoya Oshichi - Oshichi the greengrocer's daughter - in a play given in March 1809 at the Morita-za. ¶ The Iwai-gushi, a crescent-shaped comb designed by Hanshirō for use in the role of Mikazuki Osen, was considered very chic and became the rage among style-conscious ladies. It was one of the numerous things described as having iki, the commoners' word for aplomb, dash, and spruceness." (Ibid., p. 84)

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Kunisada. It is in the Lyon Collection. Click on that image to see the whole thing and a lot more interesting information about it.

|

|

Iwai Kumesaburō II |

二世岩井粂三郎 (a correction)

いわい.くめさぶろう |

Kabuki actor 1799-1836 1 |

|

Iwai Kumesaburō III |

三世岩井粂三郎

いわい.くめさぶろう |

Kabuki actor 1829-82. He also performed under the name of Iwai Hanshiro VIII. 1 |

|

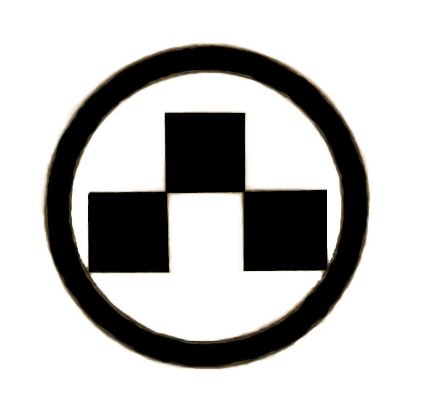

Izumiya Ichibei |

和泉屋市兵衛

いずみやいちべ え |

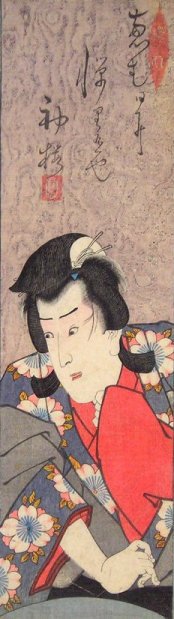

Publisher who also acted as a censor. His gyōji seal is seen to the left. Seen on prints in a period from III/1811-1814. It can be found on the 1813 Kunisada print shown below from the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Izumiya Ichibei was also a major publisher.

|

|

LINKS TO OUR OTHER INDEX/GLOSSARY PAGES Click on any of the pages listed below!

|

||

|

The photo of grapes was posted at commons.wikimedia by Péter Jankó. They aren't Japanese grapes, but they were too beautiful to pass up. |