Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画Kansas City, Missouri |

|

|

Index/Glossary

Hakama thru Hikimayu |

|

|

|

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Hakama, Hakkan jigoku, Hakke, Hako-makura, Hakoseko, Hakuuchigami, Hama, Hana, Hanabishi, Hanabi, Hanagami Hanagatsuo, Hanamachi, Hanami, Hanamichi, Han-eri, Hanetsuki, Hanezu, Hangon Haniwa, Hanji-e, Hanmoto, Hannya, Hanshita, Hanshitagaki, Hara Budaya, Haraegushi, Hariko, Harimaze, Harimise, Hashika-e, Hashira-e, Hashira maki no mie, Hasu, Hatamoto, Hayagawari, Hebi, Hechima, Heian Period, Heike-gani, Heishi, Heko-iwai, Hengemono, Hentaigana, Hi, Hibukuro, Hikimaku, Hikimayu

袴, 八寒地獄, 八卦, 箱枕, 筥迫, 箔打紙, 濱 or 浜, 破魔矢, 花, 花菱, 花火, 花紙 or 鼻紙, 花鰹, 花街 or 花町, 花見, 花道, 半衿, 羽根突き, 朱華, 反魂香, 埴輪判じ絵, 版元, 般若, 版下, 版下書き, 祓串, 張子, 張交図, 張り見世, 麻疹絵, 柱絵,

早替り,蛇, 糸瓜, 平安時代, 平家蟹, 瓶子, 変化物, 変体仮名, 日, 火袋, 引幕, 引眉 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Hakama |

袴

はかま |

Wide legged trousers: Some sources describe it as a "man's formal divided skirt". Reading The Pillow Book of Sei Shōnagon finally answers for me the question of which sex wore these garments. Ivan Morris in footnote 336, p. 331, "Hakama (trouser-skirt or divided skirt worn by men and women..." Now we know. In a book review written by S. Yoshitake of Wilfrid Whitehouse's Ochikubo Monogatari or the Tale of the Lady Ochikubo we learn that "...both men and women began to wear [these] at an early age ..."

In kendo the hakama has seven pleats, five in the front and two in the back. "These pleats have been assigned a symbolic meaning, with each pleat standing for a particular samurai virtue." Those virtues are jin (仁) or benevolence/humanity, gi (義) or honor/justice, rei (礼) or gratitude, chi (智) or wisdom, shin (信) or truth/sincerity, chū (忠) or loyalty, and kō (孝) or filial piety, but often referred to as simply piety. (Quote and list based loosely on Kendo by Jeff Broderick.) This list corresponds to the seven Confucian virtues.

See also our entry on nagabakama.

We found the image to the left at commons.wikimedia. It shows hakama from the Barbier-Mueller collection, shown at the Musée du Quai Branly. |

|

Hakkan jigoku |

八寒地獄 |

The Eight Cold Hells

"The Eight Freezing Hells (hakkan-jigoku) and the Eight Burning Hells (hachinetsu-jigoku) were thought to be at the bottom of the continent south of Mt. Sumeru. The Hell of Incessant Suffering (abi) was considered the worst of all hells" Quoted from: The Tale of the Soga Brothers, translated by Thomas Cogan, p. 318. |

|

Hakke |

八卦 はっけ |

The 8 Trigrams: The Book of Changes summarizes the Ommyōdō formulation of both time and space. It depicts yin as two broken lines and yang as a whole line and identifies sixty-four hexagrams (arrangements of six yin and/or yang lines) considered to depict all possible combinations of the two forces in the universe. These sixty-four are formed by using cominations of eight basic trigrams (arrangement of three yin and/or yang lines), that are called the Eight Trigrams (Mandarin: pa kua; Japanese: hakke). (Quoted from: Spirit Tree: Origins of Cosmology in Shintô Ritual at Hakozaki by E. Leslie Williams, p. 70)

"The best known of the many

line ornaments found in Chinese arts and crafts is the pa-kua

八卦 consisting of eight trigrams

arranged in

To the left is a detail from a Kuniyoshi print. To see that page click on the image. |

|

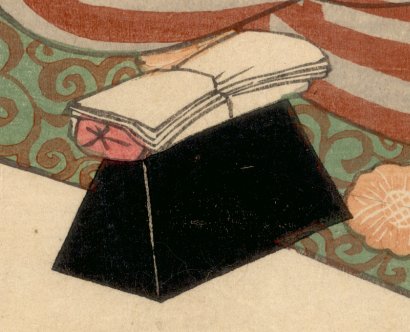

Hako-makura |

箱枕

はこまくら |

Box pillow: The evolution of the pillow must be a common trait among all groups. In ancient Japan it was said to be bundles of straw or wooden blocks. Large families were said to use a single log. The same was true for workers and apprentices. In the morning "...the father or employer would strike one end with a hammer to wake them up..." In time the hako-makura was invented and a small padded pillow was added to the top.

Eventually these box pillows became more elegant and delicate and were raised in height since the were set just beyond the futon. "This type of makura was used because the people, both male and female, dressed their hair elaborately in olden times and they did not wish to spoil the coiffure while sleeping. They rested their neck on the hako-makura wile their head would be free." Quote from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, p. 42. 1 |

|

Hakoseko |

筥迫 はこせこ |

"Women have never followed the male fashion of wearing the inrō, etc., suspended from the obi by a netsuke. Instead they have contented themselves with carrying a hakoseko..., or ornamental oblong wallet of specially woven silk or velvet, thrust into, but not entirely concealed by, the left bosom of the robe. This would contain the usual supply of soft paper handkerchiefs (hanagami), a small metal mirror, a powder-puff (mayuhake) and other small 'vanity' paraphernalia. Men carry pocket-books (kamiire) of quieter appearance... which they do not consider it necessary to display as in the case of the other sex ; these are also of flatter form and are not supplied with miniature toilet-sets." Quoted from: Publication: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1920, pp. 13-14.

"Both men and women sometimes wore a decorated cloth pouch (hako-seko) to hold sheets of paper (tatō-gami)." Quoted from: Japan Encyclopedia by Louis Frédéric, p. 5. |

|

Hakuuchigami |

箔打紙 はくうちがみ |

A special paper used in the preparation of gold and silver foil 1 |

|

Hama |

濱 or 浜

はま |

Censor whose seals were used in the 1840s & early 1850s. Full name Hama Yahei - 浜弥兵衛. 1 |

|

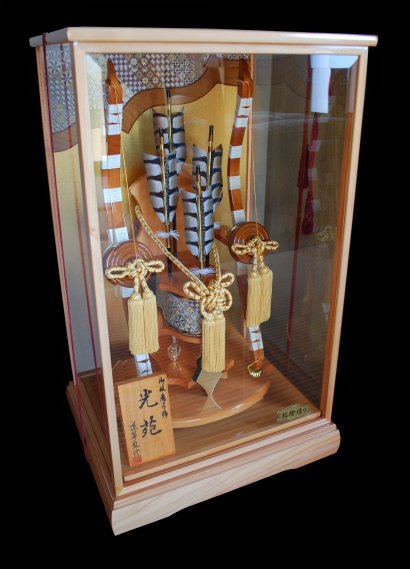

Hamaya |

破魔矢 はまや |

A Shinto ceremonial arrow used to drive away evil.

The image below was posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Katoris.

|

|

It can also be described as a demon-quelling arrow. Here 魔 means demon or evil spirit. E. Leslie Williams in Spirit Tree: Origins of Cosmology in Shinto Ritual at Hakozaki notes on p. 155 that "The popular idea exists that amulets and talismans are only effective for the year in which they are bought. At the end of the old year, these ritual items must be returned to the shrine to be burned..." and new ones must be purchased to replace them.

The hamaya is the most commonly purchased amulet at New Years which is then taken home and displayed to absorb evil spirits throughout the year.

Louis Frédéric in the Japan Encyclopedia (p. 283) says that after purchasing the arrows the visitor to a shrine places them "...between the backs of their necks and their collars." Later he adds that "Hamaya, adorned with white feathers and with a kabura ('turnip-shaped' whistle) in their heads, are still placed on rooftops of newly built houses to ward off bad luck."

A hamayumi or small bow is given to a new born male at his first New Years celebration. |

||

|

|

||

|

Hana |

花 はな |

Japanese term for flower or a beautiful woman 1 |

|

Hanabishi |

花菱 はなびし |

A flower shaped family crest |

|

Hanabi |

花火

はなび

|

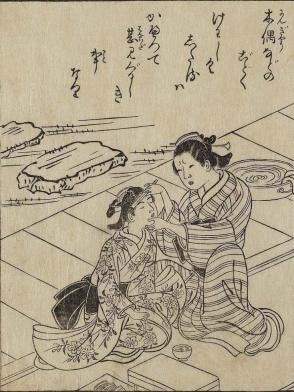

Fireworks

Thanks to our generous correspondent E. we are able to show you two very different images illustrating the Japanese enjoyment of fireworks. The top one is a detail from a print by Kuniyoshi of a public viewing whereby boatloads of spectators are out on the water oooing and aaahing - in Japanese, of course. The second image on the left is a detail from a book illustrations by Utamaro showing a boy lighting a 'pinwheel'. Look closely and you will notice the flame he is using to ignite the fuse. This is the more private experience. Close up and personal.

Thanks E!

|

|

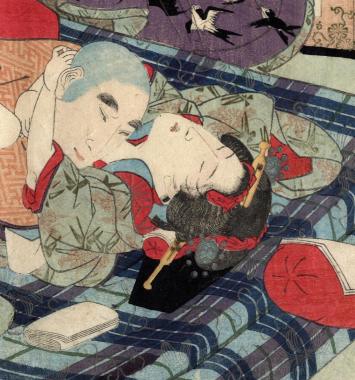

Hanagami |

花紙 or 鼻紙

はながみ |

Tissue paper, paper handkerchief: "Handkerchiefs were introduced to Japan only in the early Meiji days. The people have always used paper for blowing their nose or wiping their hands and mouth. The use of paper in this way is quite old. As it si recorded that the Chinese were already using paper in this way in the sixth century, the custom must have come to Japan about the same time. ¶ It has become etiquette for the Japanese to carry neatly folded hanagami (tissue paper) in one's bosom or sleeve." Quoted from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese, by Mock Joya, The Japan Times, Ltd., 1985, p. 15.

"The hanagami used by Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the 16th century administrator, is still preserved at the Myoho-in Temple, Kyoto. It is interesting to note that at the Vatican Museum there is displayed hanagami carried by Hasekura Rokuemon, who ws sent to see the Pope by Lord Date Masamune in 1615. The paper carried by the envoy must have greatly interested the Romans and is still preserved there. ¶ anagami is originally meant for toilet purposes, but it also has many other uses. It often takes the place of little dishes for placiong sweets." (Ibid.) |

|

Hanagami is often seen in Japanese pornographic imagery. Below is a detail from a detail from a print in the Lyon Collection. To see the whole image click on the picture below, but be FOREWARNED - not only is it a shunga image, i.e., pornographic, but it is a homosexual theme, too. |

||

|

|

||

|

Hanagatsuo |

花鰹

はながつお |

Dried bonito shavings: You can find it under hanakatsuo (flower bonito) or katsuobushi (鰹節), too.

To the left is a wreath made of dried bonito just waiting to be flaked. This comes from a Hiroshige illustration. Above is a block of dried bonito which was posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Andy King50. |

|

The Connoisseur's Guide to Fish & Seafood by Wendy Sweetser (p. 202) it says of bonito flakes: "Produced in Japan by steaming, drying, smoking and curing fresh bonito until it becomes hard enough to be shaved into flakes, a process that takes six months. The shaved flakes are an essential ingredient in the Japanese soup stock, daishi."

In 1,001 Foods to Die For it notes that when serving wafer-thin sashimi shaved bonito flakes are included in the ponzu sauce (ポン酢醤油) which also includes soy, lemon juice and a light rice wine. "Now largely sold in packets, bonito flakes used to be literally shaved off a curved block of the fish and bear a strong resemblance to wood shavings. (In Chinese they are known by the name that traslates as 'firewood fish'.)" (p. 274)

See also our entry on katsuo. |

||

|

|

||

|

Hanamachi |

花街 or 花町

はなまち |

Red-light district: Literally 'flower street' or 'flower town'. The term itself is a euphemism for the term 'pleasure district' which in its turn is a euphemism for... We are sure you know the grittier expressions.

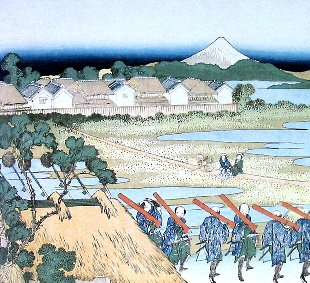

To the left is a detail from a print by Hokusai from a series of 36 views of Fuji. In the middle ground is an enclosure with structures. Those are the 'pleasure houses' of Senju, its hanamachi. It dates from the early 1830s.

Most Western references to hanamachi are centered around geisha. Other than that there is little solid informatin to be found on the Internet using this term. |

|

Hanami |

花見 はなみ |

Cherry blossom viewing (or the viewing of any other flower) |

|

Hanamichi |

花道 はなみち |

A raised walkway through an audience to a stage |

|

Han-eri |

半衿

はんえり |

A replaceable neck piece or collar - "When the ceremonial kimono is worn, the han-eri (neck band) must always be white; thus the phrase shiro-eri mon-tsuki (white collar and crest) has much the same meaning for us as 'black tie' has in the West." Quote from: Japanese Etiquette an Introduction, pp. 68-69.

In The Kimono Inspiration: Art and Art-To-Wear in America han-eri is described as "A decorative neckband that covers the juban's collar." (p. 192) The juban is an undergarment.

The New Nelson Japanese-English Character Dictionary defines 'han'eri' as "a quality collar for an under kimono".

The image to the left was posted at commons.wikimedia by Hazel88. Below is an Ito Shinsui print from 1929 called A Neck Collar.

|

|

"The collar (han-yeri) which protects beyond the outer dress or kimono is attached to the shita-juban and is almost always of a richer material than the body of that inner garment." Quoted from a 1922 publication of the Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, pp. 43-44.

"The The under-kimono (shi- tagi) is occasionally of light color, but the collar (han- yeri) which projects beyond the outer garment as in the case of the woman's costume, is always of black for winter and of white silk for summer wear." Ibid., p. 52.

"Sometimes a chemisette, or han-yeri, of

delicately worked or embroidered silk is worn under the kimono to

show a pretty edge round the open neck and to keep the chest warmer as

well." Quoted from: The Real Japan: |

||

|

|

||

|

Hanetsuki |

羽根突き はねつき |

"...a game played by women at New Year's and is similar to the Western game of badminton. Hanetsuki is played without a net, however, and can be played alone." (Source: The Shogun Age Exhibition, cat. entry #268, p. 259)

Hane (羽根) means 'feather'. |

|

Tan Taigi (炭太祇: 1709-1771) wrote:

playing hanetsuki unaware of the ways of the world they run boisterously

hanetsuku ya yo gokoro shiranu ōmatage

This is quoted from Haikai Poet Yosa Buson and the Bashō Revival by Cheryl A. Crowley, p. 83.

According to Michiko and James Vardaman in their Japan from A to Z: Mysteries of Everyday Life Explained: "The original meaning of the game concerned enabling its player(s) to avoid the bite of the mosquito in the year to come. The shuttlecock resembles a dragonfly, and everyone knows that dragonflies are helpful in decreasing the mosquito population. Therefore, one's protection from the troublesome insect grows in proportion to the length of time that the shuttlecock stays in the air." |

||

|

|

||

|

Hanezu |

朱華

はねず |

A color which is the combination of kuchinashi and benibana. This color was mentioned in the Man'yōshū. In the Nihon Shoki it is mentioned as an imperial color worn by the emperor and by princes. It was listed in the kinjiki (禁色), the codified code of the Heian period as one of the colors worn at court. Others were forbidden to wear it. In fact, kinjiki literally means 'forbidden colors.'

Ōtomo Sakanoe no Iratsume (大伴坂上郎女: born between 695 to 701 - died in ca. 750) composed 84 poems which were included in the Man'yōshū. One of them mentions hanezu, which was a difficult color to capture and to hold.

I swore not to love you, |

|

Hangon kō |

反魂香 はんごんこう |

"...incense which supposedly allows the spirit of a departed loved one to be seen in the smoke". |

|

Haniwa |

埴輪

はにわ |

"Haniwa are ritual objects that were made during the Kofun period (3rd to 6th century A.D.) for burial in tombs. Haniwa take many forms, with some, like this fine example, showing detailed representations of the equipment of armored warriors of the period." This is a quote from the curatorial files at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in reference to one of their pieces but is also applicable here.

The Encyclopedia Britannica says: "Haniwa, (Japanese: “circle of clay”) unglazed terra-cotta cylinders and hollow sculptures arranged on and around the mounded tombs (kofun) of the Japanese elite dating from the Tumulus period (c. 250–552 ce). The first and most common haniwa were barrel-shaped cylinders used to mark the borders of a burial ground. Later, in the early 4th century, the cylinders were surmounted by sculptural forms such as figures of warriors, female attendants, dancers, birds, animals, boats, military equipment, and even houses. It is believed that the figures symbolized continued service to the deceased in the other world.

The image to the left is from the collection of the Tokyo National Museum. It was posted at commons.wikimedia by Daderot. |

|

Hanji-e |

判じ絵

はんじえ |

A rebus: When I was small I remember playing with books filled with picture puzzles. Clearly they were created for my age group and skill level and were probably a very good learning tool. Even as I grew older the rebus continued to show up in everyday life. For example, "I (heart) New York" is known and understood by all. Or, nearly all. However, sometimes the rebus plays a more significant role - be it political or sinister or politically sinister. Timothy Clark notes in the Utamaro catalogue that "Although the use of picture-riddles in various series was certainly a playful pictorial device, it also started out as a necessary response to the edicts of 1793 forbidding the inclusion in prints of the names of women other than Yoshiwara courtesans. By another edict of the 8th month, 1796, these picture-riddles were forbidden [themselves]..."

Quote from: The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, text volume, p. 167.

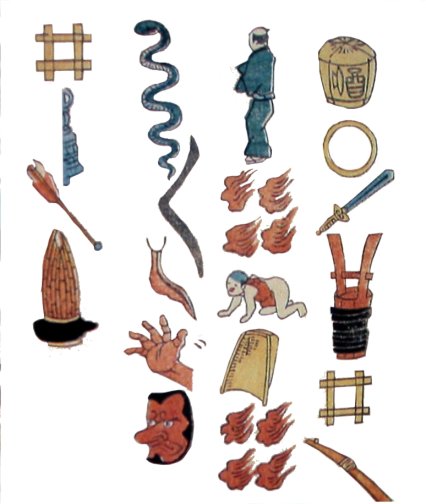

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Kuniyoshi created decades later. |

|

Hanmoto |

版元 はんもと |

Publisher - In a doctoral dissertation at Harvard in April 2017 Kit Brooks wrote: "Hinohara Kenji has drawn attention to the suggestive differences between the modern term “publisher” (shuppansha 出版社) and the Edo-period term hanmoto 版元, which is often used as its equivalent. Hanmoto were the bodies through which printed works were issued, but they were also responsible for determining their content and assigning labor to the craftspersons involved in their production. Hanmoto identified prospective or popular niches in the market and commissioned artists and writers to undertake specific projects, which were then sold through their own ezōshi-ya and jihon’ya. Hanmoto therefore had a great deal of creative control over printed ukiyo-e works, a nuance that is suggested by the meaning of the characters “han 版” and “moto 元,” as “origin of the block.” The role of these publishers in overseeing the content of the works sold in their stores has been underestimated, and is only recently receiving scholarly attention" |

|

Hannya |

般若

はんにゃ

|

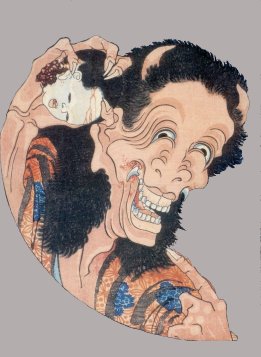

A female demon most poignantly portrayed by a frightening mask worn in certain Noh dramas.

In an entry on hannya masks Mock Joya states: "As to the origin of this fierce female mask, it is traditionally said that there was once a very jealous woman, and in his attempt to cure her of evil, a Buddhist priest named Hannya-bo (般若坊) carved out such a mask to impress upon her how ugly she was at heart."

"The hannya mask also seems to have some connection with the hannya sutra of Buddhism [the kanji is the same]. In the Noh play named Aoi-no-ue, the vindictive ghost of a woman causes the suffering of many persons, and a priest prays for her salvation, chanting the hannya-kyo sutra, and then the evil spirit disappears."

Quotes from: Mock Joya's Things Japanese (p. 403)

The demonization of women as everyone knows is not limited to the Japanese. One woman's weakness causes the Fall. To be fair the man was weak too and deserve much of the credit. Pandora opens the box, Helen causes the war - although in both cases there were underlying circumstances well beyond their control. But still, even with the advancements women have made in the last century old bigotries die hard. Perhaps that is one of the reasons why an anagram for mother-in-law can be so bitingly witty: Woman Hitler.

A puzzling connection: As noted above the kanji for hannya has two diametrically opposed meanings. However, this is not completely inscrutable. Remember that the fierce and daunting image of Fudō Myōō which to the unaccustomed eye would seem evil is actually just the opposite. He saves souls where it would look likes he would be punishing them. There are other such examples within East Asian traditions and this should serve as an object lesson that appearances can most certainly be deceiving.

The top image to the left is a detail from a print by Hokusai while the one below that is isolated from a print by Yoshitoshi.

A noh mask from the Tokyo National Museum.

"A vampiric demon from Japan, the hannya (“empty”) feeds exclusively off truly beautiful women and infants. It is described as having a large chin, long fangs and and horns, green scales, a snakelike forked tongue, and eyes that burn like twin flames. ¶ Normally, the hannya lives near the sea or wells but it is never too far from humans, as it can sneak unseen into any house that has a potential victim (a sleeping woman) inside. Just before it attacks, the hannya lets loose with a horrible shriek. While the woman is in a state of being startled, the vampire possesses her, slowly driving her insane, physically altering her body into that of a hideous monster. Eventually it drives her to attack a child, drink its blood, and eat its flesh." Quoted from: Encyclopedia of Demons in World Religions and Cultures by Theresa Bane, p. 157. |

|

Hanshita |

版下

はんした |

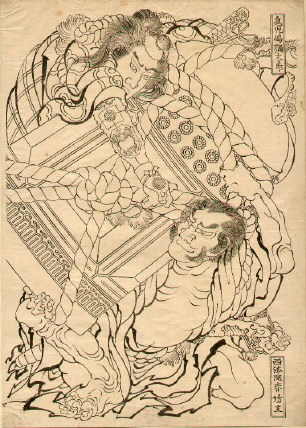

Line drawing laid down on the keyblock for carving. The example shown here is attributed to Hokusai. It is illustrated in an article in "Andon" by Richard Illing entitled "Hokusai drawings - from draft to finished print".

Properly speaking for this drawing to be a true hanshita it would have been destroyed in the publishing process. But since it wasn't it gives us a superb example of what a hanshita would have looked like.

A hanshita is a traced drawing made for cutting the keyblock. A sen-gaki is an outline drawing. |

|

Hanshitagaki |

版下書き はんしたがき |

"How did the block-printing process turn a manuscript text into a printed book in the Tokugawa period? Firstly, the manuscript was passed to a copyist, called hanshitagaki 版下書き or hikkō 筆耕, who wrote out a clean copy or hanshita, in cases where the publisher set store by the calligraphic quality of the finished product, an able calligrapher might be asked to do this, but in other cases, particularly the cheaper genres of fiction in the nineteenth century, it is clear that calligraphic quality was not a consideration and the task might be carried out in-house. In some cases authors prepared their own hanshita, or had one of their pupils do this. It is only in very rare instances that the hanshita survives, for it was normally used at once to prepare the printing blocks, but in some cases the author's own manuscript does survive, such as Bakin's manuscript of his Keisei suikoden, showing red corrections to the text and his outline sketches of the illustrations he wanted the artist to provide." Quoted from: The Book in Japan: A Cultural History from the Beginnings to the Nineteenth Century by Peter Kornicki, pp. 47-48. |

|

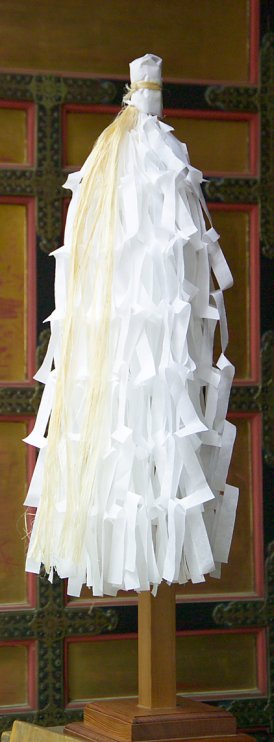

Haraegushi (or haraigushi) |

祓串

はらえぐし |

"Purification wand. A wooden stick up to a metre long with streamers of white paper and/or flax attached to the end. It is normally kept in a stand. In a movement known as sa-yu-sa (left-right-left) the priest waves and flourishes the haraigushi horizontally over the object, place or people to be purified. An alternative is a branch of evergreen (e.g. sakaki) with strips of paper attached (o-nusa); the smaller version for personal use is called ko-nusa."

Quoted from: A Popular

Dictionary of Shinto, by Brian Bocking, NTC Publishing Group, 1997, p.

45. (Bocking spells this differently: haraigushi.) To the left is a cropped photo placed in the public domain by Fg2 at http://commons.wikimedia.org/. We are grateful for the chance to use it. This haragushi is from Nikko.

The paper strips are called shide. |

|

Hariko |

張子

はりこ |

Papier mâché - "The relationship between dogs and childbirth is expressed in another manner by the administrators of Obitoke-dera sheds more light on the issue of syncretism. In Japanese folkways the dog is also considered to possess powers to ward off evil, powers called mayoke. Kuramoto Gyôkei, the head priest of Obitoke-dera, propounded these canine supernatural abilities in an interview, perhaps as an advertisement of the popular item with the cute nickname omamori wanchan, “doggy amulet.” Omamori wanchan is based on hariko inu [張り子戌], the papier maché figure of a dog placed near a sleeping baby to protect the child. Obitoke-dera’s hand-made, purse-sized dog gives us an insight into the way magic and miracle constitute a part of Obitoke-dera’s symbolic world. It also mirrors the marketing of religious strategies present in Japan’s maternity industry that I have discussed throughout this dissertation." Quoted from: 'Religion, Commerce, And Commodity In Japan's Maternity Industry' by Lisa Kuly, a PhD dissertation from Cornell, May 2009, pp. 146-147.

In footnote 127 (p. 147) to the above text it says: "Families traditionally placed a hariko inu at the lowest level of the Hina Matsuri display of dolls set up on "Girl's Day" celebration held on 3 March, though modern day doll sets do not usually include the figure of a dog."

The image to the left was posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Kuribo. It shows hariko inu or paper maché dogs for sell. |

|

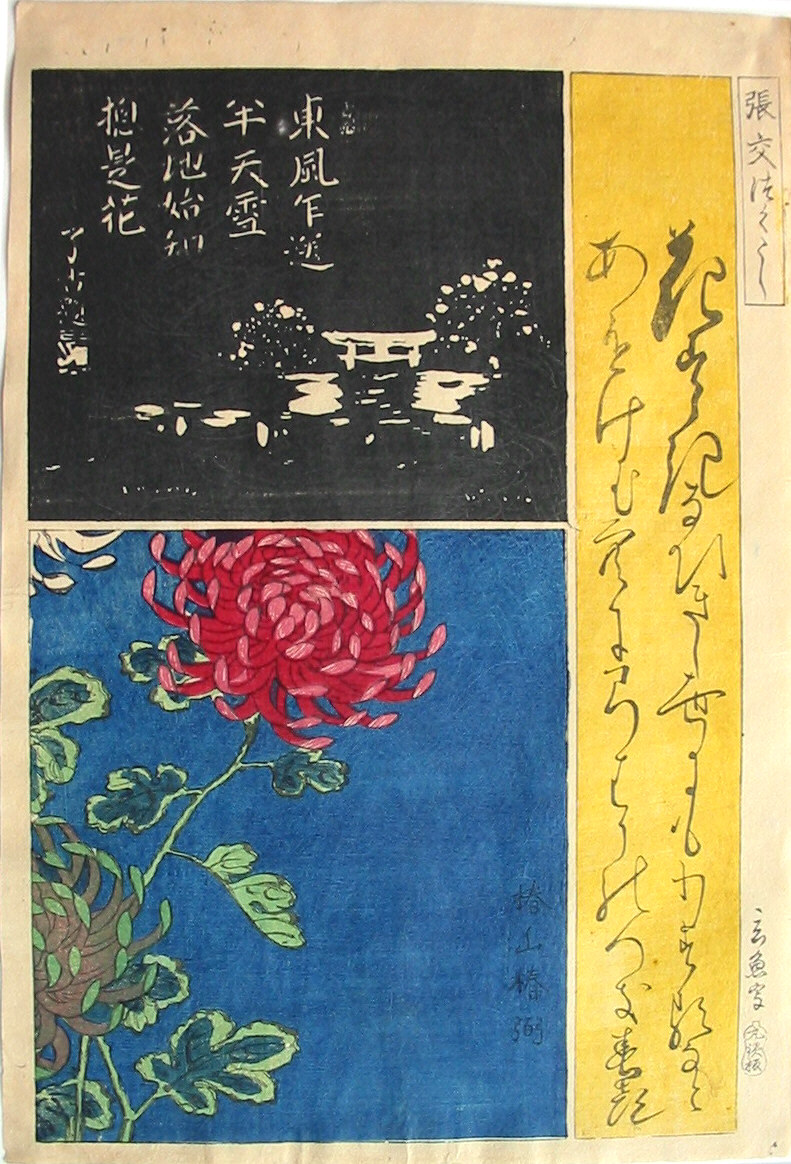

Harimaze |

張交図 はりまぜ |

A composite print with several separate images in various motifs. Often this type of print was cut by the owner into its component parts. 1 Note that occasionally these single sheets include images by more than one artist.

"Sheets of two or more subjects or designs printed on the one sheet and intended to be cut afterwards; very uncommon."

Quote from: A Guide to Japanese Prints and Their Subject Matter, by Basil Stewart, Courier Dover Publiscations, 1979, p. xv

The term harimaze is also a description used for folding screen - harimaze byōbu (貼交屏風) to which various cut-outs have been applied for decoration. These additions might be from old sections of painted scrolls, fans, religious tokens such as stamped images of the Buddha, etc. Not only that but these screens were popular before the creation of this genre of Japanese woodblock prints and were probably the inspiration for this style among publishers.

Scrapbooks could be called harimaze-cho (貼雑帖) - literally a 'paste and mix book'. [Note that the kanji is not the same as that used for the prints.]

We know that Hiroshige, Kuniyoshi, Toyokuni III, Sadanobu, Gengyo, Gekko, Yasuji and Kyōsai worked in this genre. We will add other names as we come across them. |

|

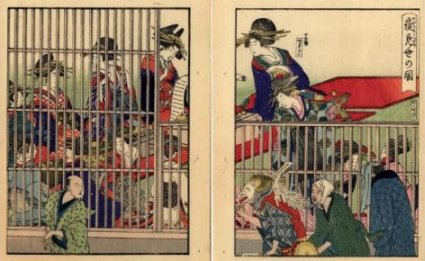

Harimise |

張り見世

はりみせ |

The lattice work of a brothels "display window."

"Establishments had a grill or cage front, behind which the women were on display. Some of the most famous print artists depicted these street scenes. Large lattice houses were the most costly, and the lowest houses had horizontal bars instead of vertical one, so a man - no matter how befuddled by sake - could not mistake the cost and class of the woman he was seeking." Quote from: Yoshiwara: The Pleasure Quarters of Old Tokyo, by Stephen and Ethel Longstreet, Yenbooks, 1989, p. 32.

"Symbolic of the system's general dehumanization of the women was the practice of harimise, or displaying prostitutes behind gratings in rooms fronting upon the thoroughfares of Yoshiwara and other big city quarters. The keepers used these 'cages' to entice customers who would then make their selections. The displays also attracted gawkers and the general public." Quoted from: Molding Japanese Minds, by Sheldon Garon, Princeton University Press, 1997, p. 97.

"Many former prostitutes recalled feeling like animals in a zoo. Writing in a noted women's journal, one summed up her five years of sitting inside the grating as 'the greatest humiliation a woman can suffer.' Bowing in large part to foreign criticism, the authorities in Tokyo, Osaka, and other cities banned the harimise in 1916." (Ibid.)

(See also magaki.)

The image to the left is from an ehon in the Lyon Collection. |

|

"Symbolic of the system's general dehumanization of the women was the practice of harimise, or displaying prostitutes behind gratings in rooms fronting upon the thoroughfares of Yoshiwara and other big-city quarters. The keepers used these 'cages' to entice customers, who would then make their selections... The displays also attracted gawkers and the general public. Regulationists in nineteenth-century Europe generally strove to make 'visible invisible.' Italian laws prohibited brothel prostitutes from standing in windows or doors, and the windows of brothels had to be covered with smoked glass. Yet in Yoshiwara, as one Western lawyer observed at the turn of the century, 'To Europeans and Americans it is a strange sight to see family parties, including modest young girls, wending their ways through the crowded streets on the night of the Tori-no-machi [festival], buying various knick-knacks and gazing at the painted beauties in their gorgeous dresses of glossy brocade and glittering gold.' Many of the prostitutes recalled feeling like an animal in a zoo. Writing in a noted women's journal, one summed up her five years of sitting inside the grating as 'the greatest humiliation a woman can suffer.' Bowing in large part to foreign criticism, the authorities in Tokyo, Osaka, and other cities banned the harimise in 1916." Quoted from: Molding Japanese Minds: The State in Everyday Life by Sheldon Garon, p. 97.

Early photo of courtesans on display in the Yoshiwara. We found this at Pinterest. |

||

|

|

||

|

Hashika-e |

麻疹絵

はしかえ |

Measles prints - "The measles kami was not deemed to have the same liking for red [as smallpox did], so measles prints tend to have the appearance of normal multicoloured prints usually combining text and image. Most of the measles prints were produced in response to the terrible epidemic of 1862 which claimed many lives. At its summer peak, Edo coffin-makers could hardly with a daily rate of about 200 funerals." Quoted from: Japanese Popular Prints: From Votive Slips to Playing Cards by Rebecca Salter, p. 122.

"Homophonous Japanese linked hashika (measles) with hashika (the beard on wheat) so wheat features in the symbolism of the illness. As prevention a holly leaf (a protector against evil spirits) was inscribed with a poem about wheat, plus the name and age of the child not yet affected and thrown into the river. As an alternative, a print might include a holly leaf and the purchaser was invited to cut out the leaf and cast it into the river instead. Legendary heroes and Shinto deities were also called upon for protection, but if the illness had already struck, the prints contained endless lists of things considered good and bad for the patient. Remedies such as the ground horn of the black rhinoceros were prohibitively expensive, so good nutrition was the only alternative. Foods considered beneficial included beans, lotus root, kumquat, abalone and apples, bad foods included eggs, aubergines, river fish, spinach and noodles. There were of course many contradictions in the list. ¶ A huge number of activities were also advised against including taking baths, sexual relations and going to the barbers; all these prohibitions had economic consequences, particularly in the pleasure quarters. More esoteric prohibitions included the smell of burnt hair, garlic, armpits, sewers, situations where people are angry or agitated and rather strangely, the sight of a woman dressing her hair. The exhalation of a drunken person who had eaten leeks and tuna was also considered inadvisable." (Ibid.)

The 1862 Yoshifuji hashika-e print to the left comes from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

|

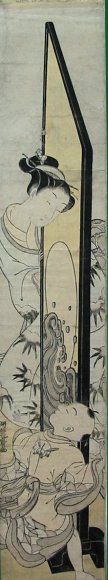

Hashira-e |

柱絵 はしらえ |

Pillar print: Roger Keyes stated in the catalogue of prints at Oberlin College that: "They were sold in paper mounts as hand-scrolls and were hung on the narrow support posts on the walls of rooms in houses." Later he added that: "Jacob Pins has pointed out that the early pillar prints were printed on a single sheet of paper, but that from the 1790s on they were printed on two sheets joined around the middle. The vogue for pillar prints diminished in the early nineteenth century."

Quote from: Japanese Woodblock Prints: A Catalogue of the Mary A. Ainsworth Collection, Roger Keyes, Allen Memorial Art Museum, Oberlin College, 1984, p. 100.

In the introduction to Pins catalogue Keyes wrote: "This is the first book in any language devoted to those miracles of grace and ingenuity, the hashira-e... The pillar print is an improbable shape, half a person's height, yet narrower than the palm of a hand."

Keyes points out the Japanese had a "...tradition of hanging long decorated strips of wood, bamboo, textile, ceramic, or paper on the hashira of buildings.... So it was natural and even inevitable that woodblock prints would eventually be designed and used as pillar coverings." Keyes goes on to tell us that Pins "...shows, the first long narrow prints appeared by accident."

Source and quotes from: The Japanese Pillar Print: Hashira-e, by Jacob Pins, Robert G. Sawers Publishing, 1982, p. 9.

Binyon referred to "...Masanobu’s magnificent hashira-ye produced about 1740 and in the following years.... One of these bears an inscription in which Masanobu calls himself the originator of the hashira-ye." Quoted from: Japanese Colour Prints by Laurence Binyon, p. 35.

To see a larger version of the print to the left click on the image. |

|

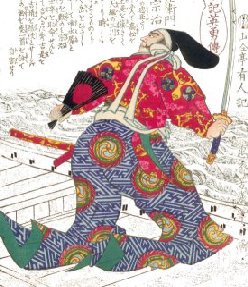

Hashira maki no mie |

柱巻の見得

|

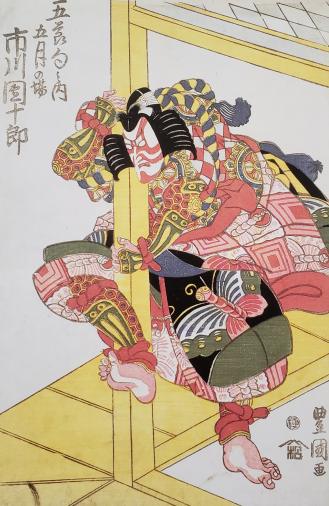

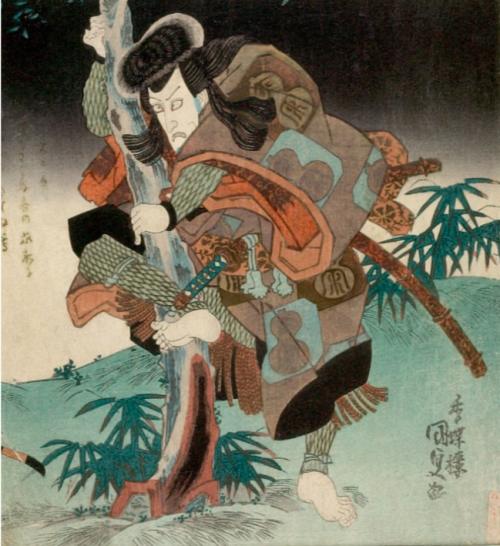

A mie is a pose. There are many variations when it comes to kabuki theater. This one is the 'pole-grasping pose'.

The images above and below are from the Harvard Museums. The print is by Kunisada. The image to the left is by Toyokuni I.

|

|

Hasu |

蓮

はす |

The sacred lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) - "It is an aquatic perennial plant that is distributed widely from Japan to China, West Asia and northern Australia. This plant grows in ponds or bogs, puts out shoots from the rhizomes in muds. Pale pink or white flowers come from July to August. There are many cultivars. This root is named lotus root, used for food. Hindu scriptures say that the cosmos was filled with water at first, the lotus-leaf was coming out of water and grew a thousand-petalled lotus flower of pure gold when the god create the womb of the universe. Thus, the lotus is the first product of the creative principle from the cosmic water."

This quote and the image to the left are from the website run by Shu Suehiro. |

|

Hatamoto |

旗本 はたもと |

"Swashbuckling and potentially violent gangs of hatamoto (banner men), young samurai who worked directly for the shogunate, were a common feature of life during the early days of Edo. Short of money, they would refuse to pay their bills; when flush, they became violent at an imagined slight when a shopkeeper might offer change for a bill paid. The 'White Hilt Gang' was typical of this unstable element on the streets of the city. Their longer than average swords were decorated like their obi (sashes) with white fittings. In summer they chose - perversely - to wear long kimonos, in winter short ones, placing lead in the bottom hems and edges of their cloths [sic] to make them swing, an effect intended to lend a swagger to their movements." (Quoted from: Tokyo: A Cultural History by Stephen Mansfield, p. 20) |

|

Hato-bue |

鳩笛 はとぶえ |

Pigeon-whistle: "Structurally, a folk-toy such as the 'pigeon-whistle'... a local product of the town of Usa (Oita prefecture), is a well-functioning wind instrument, but its primary purpose lies in the multiple layers of symbolic meaning associated with it: the pigeon is the emblematic animal of the god Hachiman (whose main sanctuary is Usa) and functions as his messenger and means of communication; the sound of the whistle, a strikingly close imitation of the bird's cooing, is, by a tangle of associations too complicated to unravel here, deemed to be highly auspicious; and the whistle itself is thought to possess a magical efficacy against children's choking..." according to Josef Kyburz in his article Omocha: Things to Play (or not to Play) With. |

|

Hayagawari |

早替り or 早変わり はやがわり |

According to Samuel L. Leiter in the New Kabuki Encyclopedia: " 'Quick-change technique,' used when actors playing more than one role in the same scene, or expressing sudden reversal of character, make quick costume and makeup changes. Also called hayagoshirae. It is one of the main categories of stage tricks (keren). Characters make radical alterations in age, sex, social status, occupation, and morality. The costumes are specially rigged by such devices as havign the obi sash sewn on the kimono itself. Occasionally, a stand-in (fukikae) is used as a means of heightening the effect. ¶ The quick-change idea had been around since early in the eighteenth century... but it began to take on special importance when two late eighteenth-century actors popularized it. The lead was taken by Asao Tamejūrō I of Osaka. In 1776, for example, Tamejūrō acted in a play in which, using a sheaf of freshly cut rice and a stalk of rice straw, he had a big hit acting both a murderer and his victim." There was a boom in hayagawari in the early 19th century. |

|

Earle Ernst in The Kabuki Theatre wrote: "The quick-change (hayagawari) , unlike the others, does not take place before the eyes of the audience but is done offstage, and it is for this reason regarded as somewhat vulgar trick by Kabuki purists..." One actor's abilities at this technique were so startling that he was called on by the authorities to answer for his actions. Some felt he used magic, while others accused him of secretly being a Christian.

"In Osome and Hisamatsu, Nanboku exploits all the possibilities of the hayagawari or quick-change technique, in which a leading actor plays several roles at once. The technique is carried to the extreme in this play, with the leading actor playing almost all the major roles. This requires split-second timing and a high level of skill, and Nanboku found an actor equal to the task ln Iwai Hanshiro V, for whom especially he wrote the play. Due to Tokugawa government restrictions, women were not allowed to perform on the stage and this led to the development of the onnagata, actors specialized in woman's roles. The art of the onnagata was refined and polished to a high degree, and Hanshiro was the leading practitioner of his day. In this play he was called on to portray practically all the types in the onnagata repertory, including a young well-bred girl, a lady-in-waiting of a daimyo house, a young man of good family, a hard-boiled brazen of a woman, a dignified motherly type, a madwoman, and a humble country wife. In some performances the lead onnagata may also take the role of a geisha." This is quoted from the 1970 abstract of a Seniors Scholars [sic] Paper by Caryl A. Callahan of Colby College. |

||

|

|

||

|

Hebi |

蛇

へび

|

Snake or serpent: The snake is one of the 12 zodiac signs. W. Michael Kelsey wrote in an article, 'Salvation of the Snake, The Snake of Salvation: Buddhist-Shinto Conflict and Resolution', in the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies (8/1-2 March-June 1981):

To the left is a picture of a Japanese rat snake. We found it posted by Yasunori Koide. It is known as an aodaishō (アオダイショウ - 青大将) in Japan. |

|

Hechima |

糸瓜

へちま

|

Sponge gourd, dishcloth gourd, loofah - Shu Suehiro's site, botanic.jp, says: "Loofah (Luffa cylindrica) belongs to the family Cucurbitaceae (the Gourd family). It is an annual herb that is native to West Asia. It was introduced into Japan in early Edo Era (about 350 years ago). The stems is a trailing vine, and the tendrils are alternate with the leaves. The yellow female and male flowers bloom in August to September. The cylindrical, 30-60 cm long fruits are borne following bloom. Its juice is used as a skin toner and its fruit is also eaten as a green vegetable. The dried fruit is also the source of the loofah or plant sponge." The image seen below is from that site.

Eliza Scidmore wrote in her Jinrikisha Days in Japan from 1891, pp. 9-10: "The waraji, or sandals, worn by these coolies are woven of rice straw, and cost less than half a cent a pair. In the good old days they were much cheaper. Every village and farm-house make them, and every shop sells them. In their manufacture the big toe is a great assistance, as this highly trained member catches and holds the strings while the hands weave. On country roads wrecks of old waraji lie scattered where the wearer stepped out of them and ran on, while ruts and mud-holes are filled with them. For long tramps the foreigner finds the waraji and the tabi, or digitated stocking, much better than his own clumsy boots, and he ties them on as overshoes when he has rocky paths to climb. Coolies often dispense with waraji and wear heavy tabi, with a strip of the almost indestructible hechima fibre for the soles. The hechima is the gourd which furnishes the vegetable washrag, or looffa sponge of commerce."

The images to the left (above) are by Querren at commons.wikimedia and (below) by Arbyreed at Flickr. |

|

Hechima sap has been referred to as 'loofah water' and was said to have several salubrious properties. It was thought to be a cough remedy even for patients with tuberculosis, while the sap was used by women as a skin lotion and the dried plant used for scrubbing. This is significant since the great haiku poet Shiki, who had tuberculosis, died on September 19, 1902 had written several death poems in the days before the end. All of them made references to hechima. (This information and poems below are provided by Yoel Hoffmann in his book Japanese Death Poems: Written by Zen Monks and Haiku Poets on the Verge of Death.)

Hechima saite

The loofah blooms and

Tan itto |

||

|

|

||

|

Heian Period |

平安時代 へいあんじだい |

One of the greatest ages of cultural flowering in Japan (794-1185). Named after the newly constructed city of Heiankyō which is now known as Kyōto. Literally "Capital of Peace and Ease." Seat of the imperial court. "...the Heian period has long been an established division of history, seen by the Japanese as the apogee of the nation's aristocratic age, when some of its finest literary works were produced and one of the world's most exquisitely refined cultural styles flourished."

It was during this period that what had been the slavish adoption of Chinese influences were assimilated and became much more truly Japanese. The reason for the original move to Heiankyō is unclear, but it may have had something to do with the court's wish to get away from the Buddhist influences on the civil service. A second reason may have been due to a struggle for power between various aristocratic factions. Superstition also played a role: The living were eager to move away from the vengeful spirits of deceased nobles.

What followed the Heian period were the feudal states of the Kamakura period - from a centralized power run by a civil aristocracy to one of dispersed militarized states.

Source and quotes from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, vol. 3, p. 165, entry by G. Cameron Hurst III. |

|

Heike-gani |

平家蟹

へいけがに |

Heike-gani or Heike crabs were "...so-called because the patterns on their shells resemble transmogrified human faces of the Heike warriors who perished at Dannoura", a sea-battle fought in 1185.

The image to the left is from a detail of a Kuniyoshi print showing the Heike trying to get revenge on their enemies.

"Another interesting Japanese crab, the Doryppe Japonica, comes more often from the Inland Sea. A man's face is distinctly marked on the back of the shell, and, as the legend avers, these creatures incarnate the souls of the faithful samurai, who, following the fortunes of the Tairo [sic?] clan, were driven into the sea by the victorious Minamoto. At certain anniversary seasons, well known to true believers, the spirits of these dead warriors come up from the sea by thousands and meet together on a moonlit beach." Quoted from: Jinrikisha Days in Japan by Eliza Scidmore, 1891, p. 42.

The image shown above was posted at Flickr by Héctor García. |

|

Heishi |

瓶子 へいし

|

Saké bottle motif: Dower in his The Elements of Japanese Design says next to nothing about this item used as a family crest. It would be hard to imagine that anyone other than a brew master would want to wear such an image. However, wrapped saké bottles were often presented as gifts to the gods and therefore would have an auspicious aura connected to them.

|

|

Heko-iwai |

へこいわい |

The ceremony when a boy is seven and receives his first loincloth or fundoshi (褌). |

|

Hengemono |

変化物

へんげもの |

Quick change performances in the kabuki theater. "The record Íor the number of quick changes in a single performance appears to be twelve, a feat matched by Utaemon III in such performances as Mataknina jūnibake ('Really again! Twelve changes') in3/1817 at the Kado Theater, Osaka.' An examination of kabuki records and surviving ukiyo-e prints indicates that the most common numbers of quick changes for single performances were seven and nine. Yet taking on so many roles was a formidable challenge for only one actor, and there were instances in which performances of hengemono were shared by several actors." Quoted from: 'Ryūsai Shigeharu: 'Quick change' dances in the Utaemon tradition' by John Fiorillo and Peter Ujlaki, Andon, 72-73, October 2001, p. 116.

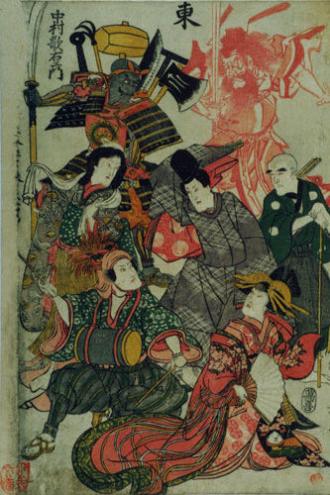

The image to the left is by Toyokuni I from the Waseda University collection and dates from 1811. It shows Nakamura Utaemon III in seven quick change costumes and roles. |

|

Hentaigana |

変体仮名 へんたいがな |

An obsolete form or kana script - It "...was derived from the fast-written grass-script style of characters." "Hentaigana-character mixed script ultimately became the norm in later periods and is the basis of modern Japanese writing. However, some other combinations still occurred in relatively recent times." These quotes are from: The Languages of Japan and Korea by Nicolas Tranter.

Hentaigana had variant forms and it would seem that it was up to the author and the moment which of those variants would be chosen. Therefore, it is very difficult to be sure how passages written in this form are to be read. It wasn't until 1900 that kana was standardized by law.

According to one source this confusion in the reading of the characters might sometimes be intentional. Hokusai may have been one artist who used this to his advantage.

Donald Richie in Viewed Sideways: Writings on Culture and Style in Contemporary Japan describes the development of four different types of script in Japan. "The fourth is the fluid sosho, from which came hiragana (or, as it was once called, hentaigana). It is so loose that it is often difficult to read and the Japanese say that anything more flowing than sosho is illegible." |

|

Hi |

日

ひ |

Sun motif crest or mon: "The circular red 'rising sun' first appeared as a popular decorative pattern on fans in the early Heian period. It was not adopted as a national emblem until 1854..." and wasn't put on the flag until 1870.

Source and quote from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 44. |

|

Hibukuro |

火袋 ひぶくろ |

The light chamber on a Japanese lantern. The kanji characters translate literally as 'fire' (火) 'bag' (袋). |

|

Hikimaku |

引幕 ひきまく |

Draw curtain in kabuki theater. "Unlike the Noh stage, which has remained practically unchanged since its inception, the Kabuki playhouse has undergone five major developments. ¶ The first occurred in the latter part of the seventeenth century with the addition of a draw-curtain (hikimaku) and the hanamichi." (Quoted from: Kabuki: A Pocket Guide by Ronald Cavaye)

The hikimaku can also be a jōshiki maku (定式 幕) or a vertically striped traveling curtain.

"While the major theatres boasted a pull curtain (hikimaku), the minor theatres only were allowed a drop curtain (donchō). The legal distinction between the 'grand' and 'minor' theatres was repealed in 1895, but the social distinction between the two theatre classes did not fade, and the nonlegal usage of terms such as 'minor' and 'major' theatre remained. Even today small-town theatres and actors are referred to pejoratively as drop-curtain theatres (donchō shibai) or drop- curtain actors (donchō yakusha), respectively. Unfortunately, using such derogatory terms fails to encapsulate the spirit of this type of kabuki." (Quoted from: Danjuro's Girls: Women on the Kabuki Stage by Loren Edelson) |

|

Hikimayu |

引眉

ひきまゆ |

The shaving off of the actual eyebrows and replacing them sometimes with pale painted on lines - or other artificial applied eyebrows higher up the forehead.

The 1748 image to the left is the left-hand page of a book, volume 2 of the Ehon masu kagami (絵本十寸鏡) designed by Nishikawa Sukenobu (1671-1750). It comes from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

|

LINKS TO OUR OTHER INDEX/GLOSSARY PAGES Click on any of the pages listed below!

|

||

|

|

This photo of the Imperial Palace in Kyoto being used as wallpaper is shown courtesy of Peppi17at |

|

.jpg)

HOME

HOME