|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

|

Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

Mawata thru Mokumezuri |

|

|

The piece of sulfur posted at

Wikimedia by |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Mawata, Meido, Meiji Restoration, Meireki, Mekura, Mempō, Menbori, Menoto, Menrui, Meshitsukai, Mezu, Mikkyō, Miko, Mikoshi, Mikoshi-gura, Mikoshi nyudō, Mildew, Mimasu,

Minatomachi, Mingei, Mino, Minogame, Minogami, Mirume-Kaguhana, Misogi, Misu, Mitate, Mitsu buton, Mitsuda-sō, Mitsu gashiwa, Mitsu tomoe, Miyagi Gengyo,

Mizaru,

Mizuko, Mochi, Moegi, Mogusa, Mokkin, Mokkotsu, Mokugyo, Mokumezuri

真綿, 冥途, 明治維新, 盲, 面彫り, 乳人, 麺類, 召使, 馬頭, 密教, 御子, 神輿, 神輿倉 or 神輿蔵, 見越入道, 黴,

三升,

源為朝, 港町, 民芸, 蓑, 蓑亀, 美濃紙, 見る目嗅ぐ鼻. 禊, 御簾, 見立て, 三蒲団, 密陀僧, 三柏, 三つ巴, 宮城玄魚,

三猿,

艾, 木琴, 没骨, 木魚, 木目摺 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Mawata |

真綿

まわた |

Silk floss - "In 1789, the use of fabrics was limited for the common man as well as for the actor. All that was permitted was the use of hemp cloth and two types of plain silk: tsumugi, closely woven from heavy yarn of the cocoon of double silkworms (normally the cocoon is filled with only one worm), or mawata, spun from heavy thread from imperfect filament or silk waste taken from the contents of a cocoon broken through by a butterfly before the cocoon has been heated." Quoted from: Kabuki Costume by Ruth Shaver.

The image to the left is a detail from a Kiyonaga print, ca. 1778, at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. in a similar print by Harunobu in that same institution David Waterhouse tells us that the young woman in this image is a watasumi or low class prostitute who works at an eboshi shaping shop as a front.

The woman sits by a nurioke, "a floss shaper for making eboshi, ceremonial hats". It is covered with piece of white floss silk or mawata. |

|

Mayuzumi |

黛 まゆずみ |

Blackened eyebrows, eyebrow paint or an eyebrow pencil: After shaving off their real eyebrows early aristocratic women would sometimes paint on new false one's higher up on their foreheads. (See our entry on okimayu. There is a description there of one of the concoctions used.)

Above is a detail from a Yoshitoshi print.

眉墨 is an acceptable variant for mayuzumi. |

|

Meido |

冥途 めいど |

Land of the Dead (in Hell): In Buddhism this is described as "...the ghostly realm of gloom."Described as the place where miscarried or aborted fetuses and deceased young children go until they are rescued by Jizo. R.E. Florida wrote at the Digital Library & Museum of Buddhist Studies: "During the day there, they try to make the best of it and play with the pebbles they find [...on a deserted river bank called Saino-kawara], stacking them into the form of little pagodas. This play is more than it seems as their building of pagodas, for the benefit of their surviving relatives, is a powerful act of merit. However, when night falls, they become cold and afraid of the dark, and to make things worse malicious demons come and destroy their little structures." |

|

Meiji Restoration |

明治維新 めいじいしん |

Restoration of Imperial power in 1868 1 |

|

Meireki |

明暦

めいれき |

The reign period from 1655-58. During the third year of this era Edo was destroyed in the Great Fire. It lasted two days. "In the conflagration, literally thousands of mansions and great temples were destroyed, and well over a hundred thousand lives were lost. From the ashes of Edo soon arose, however, a new city, partially freed from the oppressive influence of Kyoto civilization, and gradually successful at fostering a characteristically Edo style of life and culture. In ukiyo-e, the Meireki Period marked an early peak of genre book illustration in Kyoto, including courtesan critiques that were to strongly influence Edo ukiyo-e of the following decades." Quoted from: "Historical Eras in Ukiyo-e" by Richard Lane in Ukiyo-e Studies and Pleasures, Society for Japanese Arts and Crafts, the Hague, 1978, p. 28.

To the left is an illustration from a book published in 1657. It is from the Genji mokuroku ( 源氏目録). |

|

Mekura |

盲 めくら |

Blindness: "The blind have played a key role in the history of Japanese shamanism. Most shamans were women, but blind men also served in this capacity. Even today in certain remote regions of northeastern Japan, a few old blind women still occasionally practice a sort of divination which is the modern remnant of shamanic tradition. In pre-Buddhist Japan, the blind were apparently understood to be particularly capable of communications with the gods. In more recent times as well, the congenitally blind in some areas have been trained from childhood to become shamanic intermediaries. This underlying belief in the spiritual 'sight' of the blind also helps account for the large number of blind biwa hōshi and even the existence of blind 'picture explainers.' " Buddhism, on the other hand, had a totally different approach. Anyone who was congentially blind, deaf, mute, lame or suffering from leprosy was not closer to the gods, but further from them. They were being punished for wrong-doings in a previous life. (Source and quotes: The Legend of Semimaru Blind Musician of Japan by Susan Matisoff, p. 22)

Note: There are a number of Japanese words for blindness. We have chosen this one even though English is our first language. |

|

Mempō (also menpō) |

めんぽ |

A half mask worn over the cheeks, chin and nose. NOTE: This next quote seems to contradict what we have just said. Once we have figured it out we will try to make all of the appropriate corrections. "According to Stone, there were five basic types [of face masks.] The first covered the entire face (mempo, membo, so-mempo) with removable pieces. The second covered the face below the eyes (hoate). The third covered the cheeks and chin, leaving the nose and the mouth exposed - thus resembling a monkey's face (saru-bo). The fourth covered the lower part of the face (often the chin only) and was referred to as swallow-face (tsubame-bo, tsubame-gata). The fifth covered the forehead and cheeks only. The masks which covered the chin had a hole (asa-nogashi-no-ana) to allow the perspiration to escape.... (A handkerchief, or fukusa, was worn between the mask and the chin.)" (Quoted from: Secrets of the Samurai: The Martial Arts of Feudal Japan by Oscar Ratti and Adele Westbrook, p. 217)

"These face masks... were patterned to represent 'faces of men, demons, or animals, and were cleverly made, old men selecting a youthful mask and vice-versa.' " There was the Korean face (korai-bo), the ghost (moriyo), the evil demon (akuryo), the Southern barbarian (namban-bo), the long nosed tengu, the old man's face (okina-men), that of a youth (wara-wazura) and even a woman's face (onna-men). (Ibid., p. 218)

The image to the left was taken by Pom² at the Musée Guimet and posted at commons.wikimedia.org.

See also our entry on sōmen. |

|

Menbori |

面彫り めんぼり |

Face carver: Now this is an odd term because as far as we can tell it only appears once in all of the literature on ukiyo prints in an article by Shigeyoshi Mihara in Monumenta Nipponica (Vol. 6, No. 1/2, 1943, pp. 245-261). That's it. No one else seems to use this term although one would expect that they would if this is being used properly. ¶ Rebecca Salter in her Japanese Woodblock Printing (p. 60) makes it clear how difficult certain carving tasks could be. "The apprenticeship of a carver would last at least ten years. He would start by carving very simple letters on scraps of leftover wood, would move on to carving the script for song books before graduation to the plain colour blocks for nishiki-e. He would still not be allowed to cut the single brush stroke outlines but could cut the patterns on textiles. In such spare time as he had, the apprentice would practice spacing these geometrical patterns with a compass and ruler because the artist rarely did more than give an indication of the textile patterns required of large areas on the blocks before learning the art of cutting the figure. ¶ His figure-carving career began with the hands and feet and, after mastering finger tips, he was allowed to cut the nose which had to be done in one pull and there was no chance of rectifying any mistakes. The ear and head including the outline of the face came next. This part of the composition called for considerable experience and judgment on the part of the carver. The aim at all times was to preserve the freshness of the brush-drawn line on the original drawing so if possible the carving was always done in the same direction as the brushstroke. The brush line, however, would be wider than the final printed line so it was up to the carver which side of the original line he followed and by how much he reduced the width. A true master carver was capable of carving a face line characteristic of each artist without reference to a drawing."

A term which might be synonymous with menbori is kashibori or head carver. |

|

Menoto |

乳人 (or 乳母)

めのと |

"Literally a wet nurse. In fact, a menoto was more than a wet nurse for the aristocracy. The big clans used to employ women of high birth to raise and educate their children. In the menoto system, the child was often taken away from his/her real mother and trusted to the menoto to be brought up separately. It used to be accepted as the right way to raise children. In Japanese: 乳人" This is quoted directly from Kabuki21.

Our literal translation might also read as 'breast' or 'milk' person.

"In Japan, the ill-defined role and institution of wet nurse (menoto 乳母) provided a vital conduit for political and social change. From the tenth through the fourteenth century, court nobles, imperial princes, and, increasingly, provincial warriors relied on wet nurses rather than biological mothers to raise their children. Menoto became a locus of affection that was equal to, and sometimes stronger than, kinship ties. ¶ Wet nurses constituted a malleable institution of social and political power. They gained prestige in court and provincial society..." Quoted from: 'Thicker than Blood: The Social and Political Significance of Wet Nurses in Japan, 950-1330' by Thomas D. Conlan in the Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, 2005.

Another pronunciation for menoto can be uba (うば).

The image to the left is a Nagahide print showing a wet nurse. It is from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

|

Menrui |

麺類 めんるい |

One of the generic terms for noodles. Often translated as vermicelli. "Noodles in Japan can be divided into two distinct types: the buckwheat noodles associated with Tokyo and northern Japan and the wheat noodles of Osaka and southern Japan. I was born in Tokyo, and when I first went to Osaka as a young reporter, the first thing that struck me was the pallor of their noodle broth and the way you could see the noodles so clearly in it. I had always heard Osaka people were stingy, so I just assumed they used less soy sauce. Later I found out it was because they use usukuchi (light) soy sauce, which is just as flavorsome but lighter in color than the Tokyo variety. I thought they were being mean, too, with their green onions, using the tough green portion we throw away in Tokyo. But I discovered that the Osaka onions — unlike the variety I used in Tokyo cooking, which are mostly white — are mostly green. But then everything seemed so different, although the cities are only 372 miles (600 kilometers) apart. The accent — even the words used. For instance, they refer to eels in Osaka as mamushi, the name we give to poisonous vipers up north! ¶ Japan's noodles vividly exemplify this cultural division between north and south. Soba, cold-climate buckwheat noodles, are at their best in Tokyo and the north, and are mainly eaten there, while udon, those made of wheat, flourish from Osaka right down to southernmost Kyushu. Historically buckwheat noodles are the older. ¶ Oddly enough, the buckwheat variety claims more connoisseurs and sparks more controversy than udon, although aficionados of both kinds like to savor noodles al dente and eat them plain, with just the broth and nothing else. In the case of the cold buckwheat noodles served in summer, real connoisseurs hardly add any broth at all. In the urban sophistication of seventeenth-century Edo (now Tokyo), eating cold soba with a lot of broth came to be considered boorish and a sign that the eater was a country bumpkin and did not appreciate good noodles." Quoted from: Japanese Cooking: A Simple Art, pp. 305-6. |

|

Meshitsukai |

召使 めしつかい |

A servant or domestic help -

|

|

Mezu |

馬頭

めず |

A creature with a human body and a fearsome horse's head. His role in hell is to punish those who have been cruel to horses.

We found the image to the left at wikimedia.

The horse-headed figure above is a detail from a triptych in the Lyon Collection.

In the Encyclopedia of Demons in World Religions and Cultures by Theresa Bane it refers to this creature as 'Horse Faces' or 'Horse Head'. "A mortal who once held an official position in life, he was rewarded for his incorruptible integrity in death by being given a position in the nether world befitting his honesty and virtue. Higher in rank than Ox-Head, Horse Faces has the title of Constable and First Torturer. ¶ Horse Faces stands on the king’s right and in art he is portrayed as a human figure with a white horse head standing in the “breathing defiance” pose. He is often depicted as having numerous magical charms and talismans and, carrying a pronged fork or trident in his grip, brings magicians and sorcerers to their appropriate punishment. Horse Faces was once worshipped as a god of divination in Japan and a god of vengeance in China." |

|

Mikkyō |

密教 みっきょう |

Esoteric Buddhism of the Shingon and Tendai sects |

|

Miko |

御子

みこ |

The female shamans - maidens - of Shinto shrines. They are also known as fujo (巫女) or even fuyo.

An observation: Considering how pervasive Shintoism is in Japanese culture it is amazing that it doesn't show up in print images more. It does occasionally, but only in the most subtle ways and rarely if ever is the focus point. I have personal theories about why this might be, but they are only my theories and probably would just come across as hot air. However, if anyone out there reading this has any ideas on this subject I would love to hear from you. Not on to the subject at hand - the miko.

The image above shows two miko walking behind a kannushi or Shinto priest leading a wedding procession. The bride and groom are shown immediately behind the miko and sheltered beneath a large red umbrella. This photo and the isolated detail to the left is shown courtesy of Melanom and Shinichi Sugiyama as posted at http://commons.wikimedia.org/.

|

|

A miko originally was "...a medium who acts as the bridge between the people and the ancestral deities, and performs magic rituals of purification, healing, and divination." Quoted from: Handbuch der Orientalistik, by Benito Ortolani, Horst Hammitzsch, W J Boot, Bertold Spuler, Hartwig Altenmüller, published by Brill, 1990, p. 2

Chinese chronicles describe late 2nd century Japan, the land of Wa, as being engulfed by warfare. Much of the nation eventually united around Himiko* (or perhaps Pimiko) - 卑弥呼 - a young woman who may have only been a teenager at the time, but who was said to have mastered 'The Way of the Demons' or kidō (鬼道). According to the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan (vol. 3, p 139, entry by Saeki Arikiyo) Himiko's "...rule was doubtless invested with a strongly religious character. After she became queen, very few persons were allowed to see her. She is said to have had 1,000 female laves in her service, and only one male was allowed to enter her living quarters, in order to bring food, drink, and messages. Her private quarters and their palisadelike out enclosure were strictly guarded at all times by soldiers." The Handbuch der Orientalistik states that "Queen Himiko... was probably a miko.... In her exalted position as supreme ruler she might well have begun a primitive form of the ceremonies that later became the duty of the emperor as head of the Shinto religion." (Handbuch, p. 2) ¶ "...a number of kagura [sacred dances and songs of Shintoism] are still performed after sunset, because it is during darkness that the miko perform their conjurations, when the spirits of the dead appear, and the help of the protector kami against the evil influences is most needed. In general, shamanistic activity requires darkness also as a symbol for the journey of the shaman from the limits of normal consciousness into the light of the dimension where the sacred communications take place." (Handbuch, p. 6)

*It is interesting that the kanji 鬼 is the opening character for the goddess of childbirth and children, Hariti (鬼子母神), and also for witch or demoness (鬼女), and wizard or genius (鬼才) among other words.

The Handbuch (p. 22) states: "The word miko is used mainly for priestesses, female shamans/mediums, and shrine maidens, but male miko are not rare in primitive Japanese tradition. Miko were chosen through sacred lot or, in some communities, because of family tradition. Some of the first rulers of primitive Japan were probably miko, and the principal miko of the great Shinto shrines have enjoyed since their foundation a very prominent social position. ¶ It seems that originally the miko were supposed to be virgins, who would abandon their practice when they married. There are, however, many cases of miko who continued in their funcitons after their marriage. Besides the miko belonging to the shrines, there were aruki miko (wandering miko) who also would act as mediums conjuring the souls of the living and the dead, pronounce divine oracles, and pray for the faithful. A relatively high percentage of these miko were blind. A number of miko became professional entertainers and prostitutes. ¶ The importance of the miko for the performing arts cannot be overestimated. The beginning of several forms of later genres of theatre are connected with miko... The first kabuki is attributed to a wandering miko, the legendary Okuni."

Today the miko play a far different role. They are generally girls from the family of priests. "They take care of menial duties and also perform elegant, slow, dignified kagura dances, in which it is often hard to discover even a trace of imitation of the original trance phenomena." (Ibid.) In the early dances the miko became a receptacle for the kami itself. ¶ The Handbuch (p. 23) tells us that the two oldest words for dance in Japan are mai (舞) and odori (踊り). "Mai is derived from the custom of the shamaness of circling around and around to reach a state of trance (mau is a contraction of mawaru=to rotate, to move in circular motion). Odori is traced back to the fact that male shamans would leap repeatedly up and down to induce the deity to possess them (odoru means to leap, to jump)." The stamping of feet might be meant to pacify spirits, the raising of hands to welcome possession, and the linear movements meant to cover the cardinal points.

There are two other ways of writing miko: 神子, 巫子.

When a child or young adult has suddenly disappeared it was traditionally assumed that the victim has been abducted by a supernatural power. The locals would go searching the area thoroughly. "If these measures failed to bring the child back within a fixed period of time, the relatives could as a last resort request a miko or white witch to recite appropriate spells. If these in their turn did not prove efficacious within seven days the child was given up as hopelessly lost."

Quoted from: "Supernatural Abductions in Japanese Folklore", by Carmen Blacker, published by Nanzan Unviersity, Asian Folklore Studies, Vol. 26, No. 2, 1967, p. 111. For more on abductions see our entry on kamikakushi.

"In the Edo period, women known as 'wandering miko,' many of them loosely affiliated to large shrines, traveled through Japan, alone or in groups, until their activities were suppressed in 1873. The main characteristic of these women was that they were in motion, which contrasts with the relative immobility of monastic reclusion or of domestic life. The social evolution that transformed certain nuns into loose women, however, is by no means characteristic of Buddhism alone, since the priestesses (miko) of the Shintō shrines suffered the same fate. Originally, these asobime [遊び女] (courtesans; lit. 'play-girls') were perhaps sacred prostitutes... Admittedly, and the sacred were intimately connected in archaic Japanese religion." ¶ The author notes later that a Jesuit priest, Luis Fróis, visiting Japan in the late 16th century, had commented on the fact that women did not seem to value their chastity highly and that rape was not an impediment to marriage later on.

Source and quote from: The Power of Denial: Buddhism, Purity, and Gender, by Bernard Faure, published by Princeton University Press, 2003, p. 252.

The miko "...can enter a state or trance in which the spiritual apparition may possess her, penetrate inside her body and use her voice to name itself and to make its utterance. She is therefore primarily a transmitter, a vessel through whom the spiritual beings, having left their world to enter ours, can make their communications to us in a comprehensible way." (Quote from: The Catalpa Bow: A Study of Shamanistic Practices in Japan by Carmen Blacker, p. 22) ¶ "Corresponding with each of these figures is a particular kind of trance. With the medium, infused or possessed by a spiritual being a number of physical symptoms are commonly found. These include a violent shaking of the clasped hands, stertorous breathing or roaring, and a peculiar levitation of the body from a seated cross-legged posture. I have seen both men and women propel themselves some six inches into the air from this position, again and again for several minutes on end. A violent medium is always considered more convincing than a docile one, the non-human character of the voice and behavior indicating more vividly the displacement of the medium's own [self]..." (Ibid.) |

||

|

|

||

|

Mikoshi |

神輿

みこし |

A portable shrine - "The year 1095 saw the first use by these monks of a palanquin containing the presence of the god of the mountain, Sannō 山王, something that became a common sight whenever monks had a grievance. In 1123, for example, seven of these shrines for example, seven of these shrines were carried down into the capital, as a result of which a pitched battle ensued, and in 1165 a disagreement between Enryakuji and Kofukuji led to the destruction of Kiyomizudera 清水寺, one of Kōfukuji's branch temples in the capital. ¶ Kōfukuji's equivalent to the palanquin was a sacred sakaki tree 榊, known as the shinboku 神木, which symbolised the presence of the Kasuga deities and was often used to show the 'displeasure' of the gods at decisions that adversely affected temple or shrine. Sometimes just moving the tree-deity from its usual resting place to the main gate of Kōfukuji, an act known as shinboku dōza 榊木動座, was enough to insure a favourable decisision; sometimes it was taken by carefully choreographed stages all the way to the capital by a large group of peasants and laborers associated wtih the temple (shuto 衆徒 ) preceded by a similar group to the shrine (jinin 榊人) and left either at the Fujiwara college, the Kangakuin, or at Hōjōji. It was first used in this fashion as early as 1007. Warriors sent to intercept the procession often never lifted a finger to impede the passage of such a potent symbol, and matters were made worse because of a general reluctance to challenge these intimidating groups..." Quoted from: The Religious Traditions of Japan 500-1600 by Richard Bowring, p. 219.

The image to the left if cropped from a larger and much more striking photo posted at commons.wikimedia by 663highland. |

|

"For the community-at-large, the procession is the most exciting and at the same time the most meaningful part of a festival. The essence of the procession, as the Japanese term meaning "august-divine-going" suggests is the movement of the kami through the parish. This is accomplished by a symbolic transfer of the kami from the inner sanctuary to an ornate and gilded sacred palanquin (mikoshi), which becomes temporarily the abode of the kami. Actually, the sacred symbol itself usually is not removed. Instead, after an appropriate ritual, some symbolic substitute, such as a sacred mirror (shinkyo) or a gohei, is used. But in addition to the main palanquin, there are many others made by the parishioners, including some small ones for the children to carry. Within these, as a symbol of the kami, is placed a piece of paper on which the kami's name is written." Quoted from: Shinto: the Kami Way by Ono and Woodard, p. 68.

Above is a mikoshi posted at Flickr by scarletgreen.

"In 869 the mikoshi (portable shrines) of Gion Shrine were paraded through the streets of Kyoto to ward off an epidemic that had hit the city. This was the beginning of the Gion Matsuri, an annual festival that has become world famous." Quoted from: Buddha, His Life & Teachings by Neeraj Gautam.

"The sacred palanquins, the mikoshi, are so widespread today that the word matsuri evokes their image. These sometimes enormous golden palanquins shelter a divine symbol which may be quite simply a piece of paper stuck to its ceiling or a twig, a mirror, etc." Quoted from: Asian Mythologies by Yves Bonnefoy, p. 291.

"Like Taira Kiyomori, Yorimasa had also stood up to the warrior monks, but earned their admiration when he showed great respect to the mikoshi, the sacred palanquin, in which the kami was believed to dwell: 'Then Yorirnasa quickly leapt from his horse, and taking off his helmet and rinsing his mouth with water made humble obeisance before the sacred emblem, all his three hundred retainers likewise following his example." Quoted from: Samurai Commanders (1): 940-1576 by Stephen Turnbull, p. 13.

"Chancellor Moromichi Cursed for Attacking Priests: During the Horikawa reign (1086-1107), the priestly horde at Mt. Hiei had come down to the capital carrying a portable shrine in order to make demands on the Imperial court. Chancellor Moromichi , feeling that this was an impudent thing for them to do, issued orders against such activity and had the priests attacked. Some arrows struck the portable shrine itself, and an Assistant Head Shinto Priest by the name of Tomozane was injured. Consequently Moromichi was cursed [by the Kami of Hie Shrine] and soon died." Quoted from: Future and the Past: Translation and Study of the "Gukansho", an Interpretative History of Japan Written in 1219, p. 88.

In The Gates of Power by Mikael Adolphson (pp. 267-8) it says: "The monks became enraged and brought several mikoshi of Hiesha to the Konpon chūdō, where they read sūtras and called on the Hachiōji kami to bring down a curse on the regent. Moromichi fell ill, 'which everyone attributed to the Sanno god's anger.' The Heike monogatari then goes on to explain that Moromichi's mother made three vows, favoring the Lotus Sūtra and the kami on Mt. Hiei, in an attempt to have her son spared, but the god remained implacable, responding through a medium as follows: 'I can never forget the misery I suffered when the authorities shot and killed some of my priests and shrine attendants instead of granting their modest request and when others of my people returned, wounded and weeping, to complain to me of their wrongdoings.' Yet because of the lady's compassionate vows, the kami granted her son an additional three years. ¶ Though the account in some of its details is likely exaggerated, there are some useful lessons here that further indicate the dilemma for dispatched government warriors. First, they were expected to refrain from harming any of the protesters, since the latter were under the protection of Enryakuji and its deities. Second, it was a crime to damage any of the sacred palanquins regardless of the gōso's validity; an arrest for the firing of arrows at a local palanquin in 1105 represents represents another early example. In fact, the court was consistent in punishing its own warriors for such offenses. During the Hakusanji Incident of 1177, for instance, arrows were fired at some of the mikoshi, leading to the arrest of the six warriors deemed responsible." Note: A gōso (強訴) is a 'direct petition'.

"The Sanja festival (Asakusa, Tokyo, May May 17)) [sic] for example, always leaves someone injured, as the shrine porters violently crash into each other. In the Kenka-matsuri (Fight festival) of Nada, Himeji-shi, Hyōgo prefecture (October 15), porters deliberately bump the shrines into each other, hammering the roofs with poles so that the ornaments fall off. Often the collisions are so violent that the portable shrines fall over. The same happens during the Aramatsuri of Yaizu Tenjin shrine (Yaizushi , Shizuoka prefecture, August 12-13) and at the Okutsuhime shrine (Wajima-shi, Ishikawa prefecture, July 13-August 1) to mention only a few. This violent behavior is not limited to the shrines; the porters also shout obscenities and injure each other, behavior which must be forgiven and forgotten when normal time returns. The obscenities exchanged by the mikoshi carriers indicates the social leveling following the festival's abolition of all differentiation. ¶ Other such behavior appears in the so-called hadaka-matsuri (naked festivals), during the Koshōgatsu (the 'Little New Year' of January 14-16). Young men, often braving bitterly cold weather, carry their portable shrines into a river, lake or ocean. At the Dorokake-matsuri of Katori shrine (Noda-shi, Chiba prefecture, April 3) the portable shrine is taken into a pool of mud near Tone river.20 While they do so, they display the same clamorous, violently competitive behavior — running, singing, shouting, and jumping. They behave as if they were divinely possessed, surrendering themselves to a dizzy state of ecstatic exhaustion. As the kami presence gradually takes over, their procession becomes increasingly erratic and exuberant. The immersion of shrine and porters in cold water can be seen as a symbol of the death and rebirth of creation, destroyed and regenerated at the same time. ¶ These examples show how much unruly behavior still characterizes a number of modern festivals. We can only presume that ancient Japanese festivals were more violent than those of today, when the law, extending equally to ordinary and festival time, curbs such behavior out of respect for human health and safety." Quoted from: Chaos and Cosmos: Ritual in Early and Medieval Japanese Literature by Herbert Plutschow, pp. 55-56.

"When in 749 Emperor Shōmu abdicated to become a novice monk in favour of his daughter Kōken (r. 749-58), a second oracle was was reported from a kami called Hachiman enshrined at Usa in Kyushu. Hachiman expressed a desire to travel to the capital. His palanquin, the prototype of the mikoshi, was met on the road by a retinue of high officials, received at the capital and installed in a special shrine. A high-born priestess of the Hachiman shrine (who was also a Buddhist nun) then worshipped in the Todaiji in a ceremony attended by the whole court, including the retired Shomu, his daughter the Empress Koken and five thousand monks. Dances were performed and 'a cap of the first grade was conferred upon the god. Subsequently extensive lands were granted to the Tōdaiji." Quoted from Shinto in History: The Ways of Kami, by John Breen and Mark Teeuwen, p. 174.

In Classical Japanese: A Grammar (vol. 2, p. 350) by Haruo Shirane it says: "The prefix mi- was originally used to designate high places. As a nominal prefix, mi is often used with words related to the emperor, royal family, gods (kami) and buddhas to create words such as the following..." miko (prince or princess), mikoto (words of the emperor), mikari (hunting by the emperor), miyuki (imperial procession), mikoshi (carriage of the gods), mitama (spirit of a god), minori (Buddist law), etc.

"The Shrine Prototype Actual shrine structures were probably built in response to the need to summon a deity in order to offer prayers for a bountiful crop or express thanks for a good harvest. These early structures, the prototypes of the shrines we know today, are found either in a central location in a village or before mountains, boulders, and other places where the gods were thought to dwell. These original constructions were most likely temporary in nature. The configuration of the early shrines is unknown, but possibly resembled the portable shrines (mikoshi) still carried on poles during festivals today. Indeed, the arrangement of the foundation stones at Kasuga Shrine... and Kumano Shrine... suggest that their principal structures were originally moveable." Quoted from: What is Japanese Architecture?: A Survey of Traditional Japanese Architecture by Kazuo Nishi and Kazuo Hozumi, p. 40.

Some Japanese companies have been known to take kami and mikoshi to foreign sites, like Scotland, where they have established new businesses. Source: Religion in Contemporary Japan by Ian Reader, p. 76.

Women and mikoshi: John Dower in Embracing Deafeat: Japan in the Wake of WW II (p. 242) said: "Many initiatives took place locally without garnering headlines. When a neighborhood festival was resumed in Yokohama in the summer of 1946, for example, after a hiatus of five years due to the war, women for the first time ever were allowed to participate in carrying the mikoshi, or portable shrine. They thereby joined men at the center of the festivities and stepped within a Shinto circle that traditionally had excluded them for being physically and morally impure. In such ways, cherished practices associated with the 'good morals and manners' of the past began to be transformed subtly from below."

"Mikoshi or portable shrines represent another element of rural celebrations. Mikoshi vary considerably in degree of elaboration. One of the simplest is the tawara, which consists of several bales of rice secured to a wooden base. Long carrying poles extend horizontally forward and back to assist the participants in lifting the propduring processions. Others such as the yakata or 'palace' are intricately carved altars, decorated with lacquered wood and gold leaf. Both types are hoisted upwards on the shoulders of groups of four or more festival goers for use in ceremonies such as the tawara'momi (literally 'rice bale jostle'). In this noisy event, the shrines are rocked violently back and forth to the accompaniment of flute and drum music. The event is sometimes extended into a competition, as one group tries to throw the bearers of other mikoshi off balance by drowning out their beat. Shrines can even be rammed together at the height of the action." Quoted from: An Invitation to Kagura: Hidden Gem of the Traditional Japanese Performing Arts by David Petersen, p. 265.

In footnote 18 (pp. 197-8) of Ceremony and Ritual in Japan: Religious Practices in an Industrialized Society it says: "In the Tokyo area where my family and I lived during the spring of 1991, the Shinto shrine, Tomioka Hachimangu, had the first portable shrine built for them since 1923. According to the Japan Times (5 June 1991) it was presented by the Sagawa Kyūbin Company which had close connections to that area of Tokyo, Fukagawa. The 'portable' shrine (mikoshi) weighed over 4 tons, was covered with 34 kilograms of gold, diamonds and rubies, cost one billion yen to build and required 400 men and women to carry it."

Stefan Verstappen in The Thirty-six Strategies Of Ancient China it says on page 69 that warrior monks used both force and psychology to win the day: "Although feared for their fighting prowess with a naginata, the monks also employed another tactic in the form of psychological warfare. They would carry into battle a huge portable shrine, known as a mikoshi. Within the shrine it was believed there lived the spirit of one of the many gods the Yamabushi worshipped. Any offense against the mikoshi was considered an offense against the deity itself. During battle, enemy archers dared not unleash their arrows into the Yamabushi ranks for fear of striking the mikoshi and incurring the wrath of god. At other times the monks would carry the mikoshi into the town square, chant curses on the townsfolk and return to the mountains leaving the mikoshi in the village. The towns people were loath to go near it believing the town and everyone in it was cursed by its presence. Only after the townsfolk had gathered together a suitable 'donation' would the monks return and haul the dreaded shrine away."

"Analogous is a Shinto god whose presence, forever invisible, is symbolized by a shrine building, as if the shrine itself were the god. Even when the god is brought out in a festival to make his annual tour around the community, he is transferred in a mystic rite from his residential shrine into a temporary portable shrine (mikoshi) with no moment of exposure. This spatial confinement of the god likely has magical implications, for, as T.M. Luhrmann (1989) argues, invisibility generates supernatural potency. (As if to ensure invisibility and thereby maximize magical efficacy, mystic Shinto rites are often conducted in the dark, between midnight and predawn.) ¶ The emperor, then, was not only a ritual worshipper possessing privileged intimacy, including commensality, with his hidden ancestor-gods (who are central Shinto gods), but he himself embodied godlike potency, which was preserved and enhanced by his invisibility. Like a god confined in the hidden interior of a shrine, he was in no position to use his potency; instead he could only make it available to a magician outside the shrine, to 'the carrier of the mikoshi,' who invoked the name of the august one inside, hidden, invisible. Guarding the shrine of the emperor-god was the enormous bureaucracy of the Imperial Houshold Ministry." Quoted from: Above the Clouds: Status Culture of the Modern Japanese Nobility by Takie Sugiyama Lebra, pp. 346-7.

John Kenneth Nelson in A Year in the Life of a Shinto Shrine (p. 228) describes mikoshi kiyoharai as "Purification of the portable shrines." |

||

|

|

||

|

Mikoshi-gura |

神輿倉 or 神輿蔵

みこしぐら |

The structure where mikoshi are stored when not being used.

The image to the left was posted at Flickr by Jpellgen. |

|

Mikoshi nyudō |

見越入道

みこしにゅうどう |

"Mikoshi niudo is an immense bald-headed monster that lolls out his tongue, looking down over the tall folding screens." (Quote from: Fu-so mimo bukuro: a Budget of Japanese Notes by C. Pfoundes, 1875)

"A demon in folk legends, said to have a third eye on its forehead, and a very long tongue." (Quote from: Japan Encyclopedia by Louis Frédéric, p. 631)

The image to the left is taken from a print by Yoshitoshi.

See also our entry on rokuro-kubi. |

|

Mildew (kabi in Japanese) |

黴 かび |

In 1917 Ficke said: "Mildew discoloration is ineradicable." (Quoted from: Chats on Japanese Prints, by Arthur Davison Ficke, published by Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1917, p. 443)

I am mentioning this here as a warning for any serious collector. Of course, it was said in 1917 and I am not completely up on the contemporary science of conservation, but would reiterate what Ficke has said to any potential buyers or collectors. If a print has mildew all caution should be taken - even if the print is free. That is my very strong opinion. Often referred to as foxing its spread can be halted, but generally at great expense by professionals. The print should be worth the cost. I am not sure if the effects of mildew can ever be reversed completely.

In 1913 Frederick William Gookin, writing for the Japan Society in his Japanese Colour-prints and Their Designers (p. 22) called mildew "...the dread foe of the Japanese housewife..." I don't know why he singled out housewives when he was talking about this scourge, but whatever... |

|

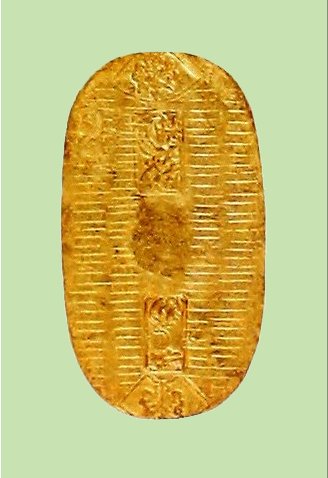

Mimasu |

三升

みます |

Masu means measure and in this case in particular it referred to measurements of rice. A triple masu crest was adopted by Ichikawa Danjūrō I (1660-1704) supposed after a fan gave him an object with this design. After that it was worn by his namesakes. There may also be another connection in that Ichikawa Danjūrō I wrote more than fifty plays for himself to star in, but he did this under the pen name Mimasuya Hyōgo (三升屋兵庫). |

|

|

三升連 みますげん |

"...the Mimasu-ren, a sub-group of the Go-gawa poetry club that served also as a fan club for Ichikawa Danjūrō V, and later Danjūrō VII." Quoted from: 'Actor surimono by Hiroshige. Kyōka circles and the patronage of poetry prints' by John Carpenter in Andon 89, December 2010, p. 55.

|

|

Mimeguri [Inari] Shrine |

三囲神社

みめぐりじんじゃ |

A shrine devoted to Daikoku and Ebisu, two of the seven propitious gods. These were patrons of wealth and fishing. Located in the Mukojima area of Edo [now Tokyo] across the Sumida River from the Asakusa district. This was an important stop along the river passage for people on their way to visit the Yoshiwara. One of the attractions was the well-known restaurants.

We found at commons.wikimedia this Toyokuni III triptych of a kabuki scene of figures near the entrance to the Mimeguri shrine.

The image to the left is a Kiyonaga triptych showing a group of visitors to the shrine caught in a sudden shower. |

|

Kunisada triptych of bijin caught in a sudden rain shower on their way to the Mimeguri Shrine. This particular example is from the Lyon Collection and shows clear references to the earlier example by Kiyonaga. Click on the image to go to the Lyon Collection piece.

"The theme of 'A Sudden Shower at the Mimeguri Shrine' had already been dealt with by Kiyonaga in a triptych in 1787. In that version there are thunder, i.e., storm demons in the sky. ¶ In the Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts in 1916 it states: "Men and women are seeking shelter in a gateway. Above, in the clouds, the demons of a thunder-storm are conferring over a haiku (a short poem in seventeen syllables) composed by the Japanese poet, Kikkaku (1661-11707). ¶ The reference is to a tradition that on the 28th of June, in the year 1693 Kikkaku went with his disciples to the Mimeguri Inari Shrine, at Mukojima, Tokyo, where, to his surprise, he encountered a crowd of highly excited farmers. Upon inquiry he learned that they had been praying for rain to terminate the long drought which threatened their crops with ruin, and in response to suggestions from his companions, coupled with the persistent appeals of the farmers, - who, because of his bald head, mistook him for a Buddhist priest, - he composed the following haiku, which he recited with great earnestness before the altar:

'If thou art indeed the God who watched over farms, send forth, I pray, thy showers!'

To the great delight of all this prayer was instantly answered, and the nourishing rain descended in torrents. The Japanese expression meaning 'watch over,' as used in the foregoing poem, is mimeguri, a homonym of the name of the Shrine. Such plays upon words are a marked characteristic of Japanese poetry."

Artists who produced prints referencing Mimeguri or its district include Harunobu, Buncho, Kiyonaga, Masayoshi, Toyoharu, Toyohiro, Utamaro, Choki, Eishi, Shunman, Toyokuni I, Shuntei, Kuniyasu, Hokusai, Kuniyoshi, Eisen, Shunko, Hiroshige, Sadakage, Hiroshige II, Hiroshige III, Ikkei, Yoshiiku, Yoshitoshi and Kiyochika. |

||

|

|

||

|

Mimi-tsuki |

耳付

みみつき |

The deckle edge of a sheet of handmade Japanese paper.

The process of paper making is incredibly labor intensive. Gathering, treating and beating fibers hardly gets at sense of it. Numerous books have been written on the subject. But here we concerned mainly with the end product, i.e., the sheet of paper.

A keta [ 桁] or wooden frame called a deckle is essential in forming sheets of paper. Liquid loaded with fibers in suspension is ladled from a vat and poured into the keta "...which is lined with a fine slatted bamboo gauze (su) held together with silk thread. The water drips through the gauze and leaves a thin sheet of paper resting on the top." The deckle is shaken to form even sheets. Repeating the ladling process creates thicker paper. The outside edges of each sheet are thinner and clearly show the deposited fibers. This outer edge is the mimi-tsuki. [Source and quote from: Japanese Woodblock Printing by Rebecca Salter, p. 40-41.] |

|

Traditionally deckle edges were trimmed. However, in the 20th century, especially in the shin hanga movement, these edges have often been left uncut and have been considered a desirable quality. These distinctive sheets are often found on the prints of Hiroshi Yoshida, Kotondo, Shinsui, Natori Shunsen, Jacoulet, et. al.

Both Hiroshi and Tōshi Yoshida have written about this deckle edge.

In his 1939 book Japanese Wood-block Printing Hiroshi Yoshida wrote: "Mimi-tsuke (paper with uncut edges) is generally characterized as good paper; the natural edges are preserved for beauty. Cheaper ones have their edges trimmed." (p. 69.)

In 1966 Tōshi Yoshida and Rei Yuki wrote in their Japanese Print-Making: A Handbook of Traditional and Modern Techniques: "Good handmade paper is slightly dark in tone, and its edges are invariably left untrimmed. Paper in this state is known as mimi-tsuki (with ears). The quality of the paper can thus be tested by drawing out the fibers in long tough threads. If the paper is of good quality, these fibers can hardly be torn." (p. 52)

The example to the left was sent to me by my great friend and supporter Mike Lyon. He told me that this sheet was made by Iwano Ichibei (岩野市兵衛), a Living National Treasure. |

||

|

|

||

|

Minamoto Tametomo |

源為朝 みなもとためとも |

We have discussed Tametomo elsewhere. He is mentioned as a god who defends people against smallpox. (See our entry on hōsō.) He is also the hero of one of Bakin's masterpieces described by Aston in his A History of Japanese Literature (published by William Heinemann, 1907, p. 355). "For intelligence and valour he had no peer. His stature was seven feet. He had the eyes of a rhinoceros, and the arms of a monkey. In strength he had no equal, and was skilled in drawing the nine-foot bow. Nature seemed to have destined him for an archer, for his left arm was four inches longer than his right. His eyes had each two pupils."

Above is the book jacket to volume 5 of the collection of the Hokusai Museum. It clearly shows Tametomo in a display of this strength. Not even breaking a sweat. (This series is a great visual resource for anyone interested in Hokusai's art.)

Tametomo is the hero of Bakin's 1805 masterpiece Yumibari-tsuke (弓張月). (A History of Japanese Literature, by William George Aston, published by William Heinemann, 1907.) Bakin wrote that at the age of 12 Tametomo was allowed to attend a lecture at court by Shinsei, a great scholar. When the topic of great archers came up Tametomo interrupted the gathering by bragging that it was moot to even discuss such matters when he, the greatest archer of all time, was right there before them. ¶ Shinsei was startled by the boy's braggadocio so a challenge was set forth. If the boy could survive arrows being shot at him by two of the best archers in Japan he would win. If not, he would most likely die. Tametomo wanted to know what he would get if he won. Shinsei said the boy could have his head. ¶ Tametomo stood before the archers and "Not only the sovereign but all present wrung their hands till they perspired, expecting every moment to see Tametomo's life fade faster than the dew beneath the sunbeams." Norishige and Norizaku let fly. Tametomo caught one arrow with his right hand and the other with his left right before it struck home near his heart. Frustrated the two archers, not wanting to kill the boy, nevertheless redoubled their efforts swearing that this time he would not be able to catch the next round. One came so fast that all Tametomo could do was entangle it with his sleeve. The other was even faster leaving the boy no option but to catch its tip between his teeth "...and at once crunched its head to atoms." Everyone was amazed because it had happened as fast as a bolt of lightening. At this point Tametomo yelled "Now, your Reverence, you will be so good as to give me your head..." Fortunately at this point the boy-wonder's father interceded and the scholar was spared. (Aston, p. 358) |

|

Minatomachi |

港町 みなとまち |

A port city. |

|

Mingei |

民芸 みんげい |

Folk art - It could be translated literally as 'people's crafts'. |

|

Mino |

蓑

みの

|

A straw raincoat.

Above is a photo of a traditional Japanese mino taken by Jnn and posted on http://commons.wikimedia.org/. Jnn placed this in the public domain and for this we are appreciative. We altered the background to isolate the image.

The image to the left is a

detail from a ca. 1838 Toyohide print showing Kanpei with his rifle and |

|

Minogame |

蓑亀

みのがめ |

Long-tailed turtle - a symbol of longevity. Actually the tail is algae growing on the backs of some older turtles. 1

There is a Japanese helmet crest, a maidate, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art which shows a minogame. "One of Taoism's four supernatural animals, together with the dragon, the phoenix and the kirin, the minogame (thousand-year tortoise) symbolises the element earth. In addition it is the embodiment of longevity, as expressed by its tail of marsh grass. The minogame is also a companion and emblem of two of the Seven Gods of Good Forturne, Fukurokuju and Jurōjin." Quoted from: The Gods of War: Sacred Imagery and the Decoration of Arms and Armor, Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 44.

Menuki from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Early 19th century. |

|

Minogami |

美濃紙 みのがみ |

A special paper made from mulberry bark. This paper is also known as kozō (楮). It is used in making the preliminary drawing or hanshita which is laid down on the woodblock surface for carving the keyblock. It has to have special qualities - mainly strength - to withstand the process which ends up in its destruction. This long-fibered paper was also used in producing traditional lacquer ware and even in puppet making. |

|

In Margaret Price's 1999 Classic Japanese Inns and Country Getaways she states that "In the days when washi (handmade paper) was made entirely by hand, Mino was one of the biggest, most active centers in the country. Echizen papers from the Sea of Japan coast were the choice of artists and calligraphers, but Mino fed the voracious appetite for books among the increasingly literate residents of Edo (Tokyo) during the Edo period. The fine blemish-free Mino paper, sold at bulk discounts, was so popular with Edo woodblock printers that the size of the Mino folding frames determined the standard sizes of books. And rather as Westerners now call crockery 'China,' the generic name for the most common scroll-mounting paper is still mino-gami. ¶ The only visible remains today of the hundreds of papermakers who once lined the banks of the Itadorigawa river are the two hon-mino-gami (genuine Mino paper) masters who are designated 'living national treasures.' Their homes still have tall boards propped out in front to dry the fruits of their considerable labor."

In a publication from 1879 professors W. E. Ayrton and John Perry stated that mino-gami was used to polish metallic mirrors because it was softer than silk.

One of my favorite sculptors from any nation in the 20th century was Isamu Noguchi. When he visited Gifu Prefecture in 1951 to watch the cormorant fishing which was done at night by torch light he was inspired to create his Akari lamps which are made up of minogami paper strips stretched over bamboo frames. I have always liked these but did not realize until I was researching this topic that it was minogami which was used. Below is a detail from a photograph of hanging Akari lights posted on the Internet at commons.wikimedia by Evrik.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Mirume-Kaguhana |

見る目嗅ぐ鼻

みるめかぐはな |

Two disembodied heads which sit atop Yama's pole in hell. They are used to judge the sins of souls which have died recently. Kaguhana, the all-smelling, can detect all bad acts and Mirume, the all-seeing, can detect all of a sinner's faults.

The two images shown here are taken from prints by Yoshitoshi. |

|

Misogi |

禊 みそぎ |

Purification - "Another type of misogi is found at the Amano Shrine in Kishu, where people carry a portable shrine (mikoshi) to the ocean beach and pour sea water over it for ritual cleansing." Quoted from: The Essence of Shinto : Japan's Spiritual Heart, p. 92.

Shinto purification by cold water. |

|

Misu |

御簾

みす |

Bamboo blinds - In the Princeton Companion to Classical Japanese Literature (p. 489) there is a drawing showing the interior of a Heian palace. Number 17 is the misu described as the "Sovereign's Bamboo Blind of State".

"During a game of kickball at sunset in the spring, Kashiwagi accidentally glimpses the Third Princess behind the hanging shades of her rooms when her cat runs out and momentarily lifts the bamboo blind (misu), stirring his feelings." Quoted from: Envisioning the Tale of Genji: Media, Gender, and Cultural Production by Haruo Shirane, p. 179.

The image to the left was posted at Flickr by mrhayata. |

|

Mitate |

見立て みたて |

Properly the translation of this term is 'selection or choice', but sometimes loosely as 'parody.' |

|

In an article in "Impressions: The Journal of the Ukiyo-e Society of America, Inc." Number 19, 1997, Timothy Clark points out that this term has often been overused and misunderstood. In fact, sometimes it is "an inventive pairing of disparate things, what I described earlier as 'a brain-teasing collision.'"

"A very common pictorial device in Ukiyo-e prints and paintings - reflecting a common pattern of thought in Edo society as a whole - was that of mitate-e, variously translated, but not completely summed up, by such English words as 'parody', 'travesty', 'burlesque', 'analogue'. The basic form of such 'parody pictures' was already apparent in certain genre paintings before Ukiyo-e had ever appeared, and consisted of an ancient tale or incident, acted out or otherwise alluded to in some way by characters wearing contemporary dress."

"The range of subjects suitable for reworking in this way was expanded and codified in a series of printed books and albums by Okumura Masanobu [奥村正信: 1686-1724] during the early decades of the seventeenth century and was often drawn from Chinese and Japanese classical literature or lore, generally reworked in Japanese No plays, popular ballad singing, or Kabuki during the intervening centuries. The tone adopted varied from outright burlesque...to...simple parallels..."

The use of the mitate was often necessitated by effort to avoid government restrictions. "...to avoid censorship by the military government of reporting of contemporary events, many plots are relocated in the distant Kamakura period and the characters given new, but similar-sounding names. Popular literature of the eighteenth century, too, made extensive use of such techniques..."

Source and quotes: Ukiyo-e Paintings in the British Museum, by Timothy Clark, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992, p. 21.

Charles J. Dunn said it best when he described a mitate as "...a term often translated as 'parody,' but implying an imaginary situation, such as did not represent an actual event, therefore better translated in my opinion as 'imaginary scene'..." Quoted from: A Kabuki Reader: History and Performance, edited by Samuel Leiter, p. 83.

"The term derives from two roots: mitateru (見立る, "to liken one thing to another") and e (絵, "picture"). The mitate technique arose first in poetry and became prominent during the Heian period (794–1185). Haiku poets revived the technique during the Edo period (1603–1868), from which it spread to the other arts of the era. Such works typically employ allusions, puns, and incongruities, and frequently recall classical artworks."

"This is a broad term that has been associated with many ukiyo-e by art historians while many of these do not have the term mitate in their titles. As Timothy Clark has pointed out in his sampling of 6,806 Japanese prints from the British Museum’s collection, more often than the word mitate, one finds fūryū (“up-todate” or “elegant”), yatsushi (“reworking”), and fūzoku (“affiliated”). See Timothy Clark, “Mitate-e: Some Thoughts, and a Summary of Recent Writings,” Impressions: The Journal of the Ukiyo-e Society of America..." Quote from a footnote by Bryan Fijalkovich.

Sarah E. Thompson pointed out in her article in "Parody and Poetry: Japan versus China in Two Eighteenth-Century Ukiyo-e Prints" Impressions in 2002 that Masanobu may have been the first print artist to use the mitate in his compositions. However, by the time of Kuniyoshi 100 years later, those same witticisms and juxtapositions that Masanobu used had become less impactful in their freshness and their capacity to shock or surprise their viewers. Thus, the same imagery as mitate had morphed into something different, something less surprising. |

||

|

|

||

|

Mitsu buton |

三蒲団

みつぶとん

|

Bedding was obviously very important to courtesan. Not only for comfort for her and her clients, but also as a symbol of prestige. Only the highest order of prostitutes were allowed to own three layers of futons - hence the mitsu buton.

Cecilia Segawa Seigle states: "The tsumiyagu, or 'display of bedding,' was another event that enhanced an oiran's prestige, though it was not as important as sponsoring a new oiran. For courtesans, bedding was a necessary professional accoutrement, of course, and receiving a set of luxurious bedding in splendid fabric as a patron's gift was an occasion for special display. The quilts (futon) and coverlets that a high-ranking courtesan used were all of silk or silk brocade thickly stuffed with light cotton. The taya and oiran used three layers of these quilts for their beds."

Quote from: Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan, by Cecilia Segawa Seigle, published by the University of Hawaii, 1993, p. 187.

Tsumiyagu may be 積夜具.

The image to the left is a detail from two prints of a triptych by Kunisada showing an actor as a courtesan in her bed chamber holding the coat of her lover. Behind her one can see the beautifully covered stacked futons. The detail on the bottom shows more clearly the three separate tiers. |

|

Mitsuda-sō |

密陀僧

みつだそう |

Lead oxide used for the pigments litharge and masicot.

To the left is a chunk of galena ore with a layer of mustard yellow massicot. It was posted at Wikimedia commons by Rob Lavinsky. |

|

Mitsu gashiwa |

三柏

みつがしわ |

A crest or mon of three oak leaves. (See our entry for kashiwa.) |

|

Mitsu tomoe |

三つ巴

みつどもえ |

A circle formed of three comma shapes. These may represent heaven, earth and mankind.

Friedrich Hirth, a German born sinologist, argued that the ancient mitsu tomoe represents rolling thunder and hence that is why the thunder god is often beating a drum with the three comma motif. "But this ornament is not at all limited to the drums of the thundergod; it is, on the contrary, very frequently seen even on the drums beaten by children at the Nichiren festival in October. At many Japanese temple festivals which have no connection whatever with the thundergod or the dragon, the same ornament is seen on lanterns and flags. Hirth explains its frequent appearance on tiles as a mean of warding off lightning, based on the rule 'similia similibus'. " This motif on tiles was believed "...to drive away evil influences..." (Source and quotes from: Dragon in China and Japan, by M. W. de Visser, reprinted by Kessinger Publishing, 2003 - originally 1913, pp. 104-5)

"I formerly believed it to be the Yang and Yin symbol, the third being the T'ai Kih ( 太極, the primordium, from which Yang and Yin emanate). This primordium, which in China is represented by the whole figure, should by mistake have been represented by the Japanese by means of a third comma. Yang and Yin, Light and Darkness, however, are represented by one white and one black figure, somewhat resembling comma's and forming together a circle. It would be very strange if the ancient Japanese, who closely imitated the Chinese models, had altered this symbol in such a way that its fundamental meaning got lost; for replacing the two white and black comma's with two or three black ones would have had this effect. Moreover, in Japanese divination, based on the Chinese diagrams, the original Chinese symbol of Yang and Yin is always used and placed in the midst of the eight diagrams. Thus the futatsu-tomoe and mitsu-tomoe are apparently quite different from this symbol, and Hirth rightly identifies them with the ancient Chinese spiral, representing thunder." (Ibid., p. 105) |

|

"...variations of the so-called 'comma' motive, signifying good luck, which include the 'three commas' (mitsu-domoye), which Raiden, the thunder-god, has marked on his drum, and the mitsu-komochi-domoye ('three pregnant commas,' three large 'commas' enclosing smaller ones)." (Quoted from: 'Guide to the Japanese Textiles' by A. D. Howell Smith at the Victoria and Albert Museum, 1919, p. 41)

This Kuniyoshi figure is from a triptych in the Lyon Collection.

"Although the yin-yang emblem in question does appear in Japan (especially in divination practices), where it is called futatsu-tomoe, or the 'two comma designs', more common, however, is the so-called mitsu-tomoe, the ' three comma designs'. Functionally identical to the dual comma-shaped yin-yang emblem, the mitsu-tomoe comprises three interlocking comma-shaped patterns in a circle, graphically representing a kind of spherical whirl design. An example of such a design is shown on the drum worn on the breast of the namazu fireman remain in the guise of the fire/thunder god Fudo... The frequent appearance of the mitsu-tomoe on objects like drums, particularly also on those objects connected with the temple and its rituals, is ascribed to its evil- averting properties. The fact that drums often featured the mitsu-tomoe design, logically leads to the assumption that the design is associated with thunder. Indeed, the reverberant sound of the drum is easily likened to the peals of thunder, and, in addition, the thunder god Raijin is usually depicted wielding a series of drums each one affixed with the mitsu-tomoe design. Accordingly, De Visser for example is firmly convinced that the comma-shaped emblems are nothing but designs indicative of rolling thunder. But there is more to it. Earlier, as it will be remembered, mention has been made of the ambivalent qualities of certain deities, differentiated as the rough spirit (aramitama) and gentle spirit (nigimitama). These two aspects, moreover, admitted of two additional spirits, the most important being the sakimitama or luck spirit. According to the details set forth by Herbert, the mitsu-tomoe actually represents these three aspects. Significant is the explanation of the sakimitama, where saki is claimed to be the function of saku (to split, to analyse, to differentiate). Based on these arguments, there seems to be little doubt that sakimitama is the mediating element that reconciles as it were the two opposing aspects of one god, or, in general terms, comprises the mediator between the dual forces of the universe, embodied by the yin-yang element." Quoted from: Irezumi: the Pattern of Dermatography in Japan by Willem R. van Gulik, pp. 168-9.

"...[the tomoe] was made the mon of the Hachiman shrine and thus represented that god of war." Quoted from: Mon: The Japanese Family Crest by Kei Kaneda Chappelear, p. 76.

The images shown above and below are details from the Tsurugaoka Hachiman Shrine. We found this at commons.wikimedia.

|

||

|

|

||

|

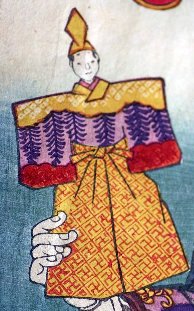

Miyagi Gengyo |

宮城玄魚 みやぎ.げんぎょ |

Artist 1817-80: He was also known under the name Baisotei Gengyo (梅素亭玄魚). He was also known as an author of gesaku (戯作) or comic compositions. There is a memorial print of Kuniyoshi done by Yoshiiku. One of the dedicatory poems is by Gengyo. He contributed art work to prints designed by Toyokuni III and some texts too.

Above is an inset by Gengyo from a print series collaboration with Toyokuni III in the mid-1850s.

|

|

Mizaru |

三猿

みざる |

The three monkeys who see, hear and speak no evil. "BY THE VILLAGE road, and more often at the dividing line between two villages there stands a koshin-zuka or a koshin stone tablet. Koshin is one of the most common deities worshipped by rural folks. As it usually stands on a village road, it is regarded as the guardian of the road or the protector of travellers. But originally it was the guardian deity for the local people." Such stone carvings are common, but according to Mock Joya no one is quite sure what they represent. However, many of these markers display the three monkeys and were known to all Japanese. Supposedly their origin is Chinese. "It is generally said that it was the Buddhist priest Dengyo (767-822) who first engraved the three wise monkeys on the koshin tablet, as he placed great value on the old teaching. If this be so, the three monkeys are a later addition to the original koshin tablet which was already an object of public worship."

The painted wood carving shown above is from the Tōshōgū shrine devoted to Tokugawa Ieyasu at Nikkō. It was said to be created by Hidari Jingorō (fl. late 16th c. to the early 17th c.:左甚五郎) who some believe was as great a sculptor as Japan has ever produced. In fact, Basil Hall Chamberlain in his Things Japanese was unequivocal in his praise: "Japan's most famous sculptor was Hidari Jingorō, born in A.D. 1594. (p. 84) Chamberlain said he died in 1634. Some legends say that his creatures come to life at night and roam about. In that Jingorō is compared to Pygmalion.

This carving is mounted above the entry to the 'stable' where the sacred white horse is kept for the use of the gods. Katherine M. Ball in her Animal Motifs in Asian Art: An Illustrated Guide to Their Meanings and Aesthetics (Courier Dover Publications, 2004, p. 122) says that these three moralizing monkeys are of Buddhist origin and are "...designed to warn against the three principal temptations."

For other images of these monkeys go to our page http://www.printsofjapan.com/Kunisada_Hear_No_Evil.htm.

The photo of this famous carving was posted at commons.wikimedia by Fg2. |

|

|

水車

みずぐるま

|

Waterwheel

The image to the left above is a detail from an 1858 Toyokuni III print. The detail below it goes with the Hokkei surimono shown below. It comes from the Marino Lusy collection. Below that is a detail from another print from that collection. This print was designed by Sadamasu.

|

|

Mizuhiki |

水引 |

A cord made of twisted paper, used in various ways in hair styles, or to wrap decorative packages. (See also our entry on motoyui.) |

|

Mizuko |

水子

みずこ

|

Archaically it meant an infant.

Later it meant a fetus, a stillborn fetus and in time it was a term used

for an aborted child. "With the dramatic rise in abortions eventually came

the creation of mizuko kuyō. Mizuko (literally 'water

baby/child') is an alternate term for a fetus, though it has largely taken

on the meaning of a fetus lost through miscarriage, stillbirth, or,

especially, abortion. Kuyō is a memorial rite, derived from the verb

'to offer,' as in to offer prayers and apologies. There are countless

varieties of kuyō in Japanese Buddhism, and they are among the most

common religious practices - everything from ancestors to sushi to broken

sewing needles receive kuyō rites. The actual procedural details of

mizuko kuyō differ according to the particular person or group

performing the rite, but they fall into several general patterns. Typically

a woman approaches a Buddhist priest and requests the service. The ceremony

is held in the main worship hall of the temple or a special shrine

specifically for mizuko kuyō (a mizuko jizōdō), where

the priest chants sutras, expresses the wish that the mizuko will

become a Buddha, and prompts the layperson to make offerings of incense,

toys and food. Often the woman purchases a small, childlike statue of Jizō,

dresses it with bibs and knitted hats, and prays to it for forgiveness; in

some temples a memorial plaque (ihai), normally used to enshrine

ancestors, takes the place of the statue." (Quoted from: Mourning

the Unborn Dead: A Buddhist Ritual Comes to America by Jeff Wilson, p.

7) See also our entry on ihai.

"Another way in which laypeople ritualize pregnancy losses that is outside the aegis of priests is by purchasing votive tablets (ema) and writing messages to the spirit of Jizō." (Ibid.)

The rather odd image to the left (above) is a detail form a Meiji period Japanese print showing a pregnant woman with a cut-away shot her fetus. The image below that is by our friend Angela. |

|

Mizusashi |

水差し

みずさし |

Water jug or pitcher: "Mizusashi were used in the Japanese tea ceremony — water drawn from the jar would be poured into the iron kettle to cool the near-boiling water." This is quoted from a Japan Times article by Yoko Haruhara from June 18, 2003.

To the left is a 17th century mizusashiin the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Ki-Seto ware. There is another photograph of this piece at Wikimedia.commons. We chose to use the Met's photo. |

|

Mochi |

餅

もち |

A sticky rice cake. It is eaten at New Year's, but not exclusively then, because it is said to bring good luck and prosperity. 1 |

|

Moegi |

萌葱

もえぎ |

A light yellowish green. The female character Omiwa (おみは) often wears this color on her kimono in the second act of Imoseyama Onna Teiken (妹背山婦女庭訓).

"Sometimes I think there must be more shades of green than any other color on earth. I love green — I find myself drawn to buy green sweaters, green pants, green handbags. But all these greens rarely match. A blue-green brings out the worst in a yellow-green, and a Kelly green doesn't go with anything. Sometimes I look down in dismay at the clash of greens as I am rushing out of the house. Often the only thing to do is to add a scarf, in yet another green, in the hope that people will think it was a deliberate attempt to imitate multi-verdant nature. ¶ One of my favorite greens is a light-hued, yellow-infused, slightly subdued shade that doesn't really have a good tag in English. If 'chartreuse' were not so high octane, it would come closest. When I was poking around in the closets of medieval Japanese empresses while researching a chapter for my book Kimono, imagine my delight to discover that this color was hugely popular in the twelfth century. It is called moegi — 'sprout green.' Embodied in the name is the freshness of the new growth that outsprouts from the earth before greening up and darkening with sun exposure. I must have been subliminally influenced by this color, the Greek name for which is khloros, when I named our younger daughter Chloë." Quoted from: East Wind Melts the Ice: A Memoir Through the Seasons by Liza Dalby, pp. 23-24.

"An ensemble called moegi no nioi would have layered ever paler yellow-green robes one upon another and been highlighted by a scarlet under-robe peeking out at the throat and sleeve. I would have adored it." (Ibid., p. 24)

In a footnote (#16, p. 651, vol. 2, A Tale of Flowering Fortunes: Annals of Japanese Aristocratic Life in the Heian Period, edited by the McCulloughs) it says: "The colors of yellowish-green combination (moegi) are usually said (on the basis of uncertain authority) to have been either yellowish-green for both the outer surface and the lining or light green for the outer surface and blue for the lining. Hagitani 1971-73, 2: 150."

Basil Hall Chamberlain defined moegi as "dark green".

In Europe, until the discovery of chemical dyes and synthetic inorganic pigments in the nineteenth century, the greens used in the fine and decorative arts were made from naturally occurring plants or minerals (sap green, malachite green). In Japan, however, there was no vegetable yielding green in isolation so that it was necessary to overdye, using first yellow then indigo. The result was that moegi (yellow-green) became the type of green most frequently found. Generally speaking, silk dyed in this way turns out an attractive yellowish-green color, but on cotton the method produces a somewhat drabber olive-green." Quoted from: The Colors of Japan by Sadao Hibi, pp. 46-48. |

|

Mogusa (or moxa) |

艾

もぐさ |

Mugwort (Artemisia princeps), moxa - "Groups of cheery pilgrims come chattering down from the forest, untie their sandals, wash their feet, and disappear within the temple; where the old priest writes sacred characters on their bared backs to indicate where his attendant shall place the lumps of sticky moxa dough. Another attendant goes down the line of victims and touches a light to these cones, which burn with a slow, red glow, and hiss and smoke upon the flesh for and hiss and smoke upon the flesh for agonizing seconds. The priest reads pious books and casts up accounts, while the patients endure without a groan tortures compared with which the searing with the white- hot irons of Parisian moxa treatment is comfortable. The Mine priest has some secret of composition for his moxa dough which has kept it in favor for many years, and almost the only revenue of the temple is derived from this source. Rheumatism, lumbago, and paralysis yield to the moxa treatment, and the Japanese resort to it for all their aches and ills, the coolies' backs and legs being often being often finely patterned with its scars." Quoted from: Jinrikisha Days in Japan by Eliza Scidmore, 1891, p. 36.

|

|

Mokkin |

木琴

もっきん |

Xylophone - The Encyclopedia Brittanica entry online is rather dismissive: "The simple mokkin xylophone found in the off-stage music of the Japanese Kabuki theatre may have come from the Chinese merchant colony of Southeast Asia or from their tea house ensembles in Nagasaki. Xylophones have not played a major role in East Asian music, however."

William Malm in Nagauta: The

Heart of Kabuki Music - "In closing one should mention the sixteen-keyed

xylophone (mokkin) borrowed from Chinese music. This instrument is meant to

support comic dances and is played in a desultory

Detail from a Kuniyoshi print in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

To the left is a Kunimitsu print from the collection of Waseda University. |

|

Mokkotsu |

没骨

もっこつ

|

Timothy Clark describes a series of three Utamaro full-figure portrait prints "...that avoid black outlines whenever possible and replace these with coloured outlines, or 'boneless' (mokkotsu) areas of colour with no outline at all."

The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, Text volume, p. 185.

Those three prints are among the greatest examples of their type. However, if you look closely you will find that elements of prints by many other artists show this 'boneless' technique as part of the overall design. To the left are two details from a Toyokuni I print showing both lined and lineless areas. To see the full print click on the number to the right. 1

In isolation the kanji characters for this term could mean 没 for hide and diappear and 骨for skeleton or bone. |

|

Mokugyo |

木魚 もくぎょ |

A fish gong (or drum) struck at a Buddhist temple while sutras are being chanted. "At a proper time after setting the food on the counter with reverence, burn incense, spread the bowing mat on the floor in front of the food counter, and make nine full bows in the direction of the monks' hall. Then fold up the bowing mat, make a standing bow, and stand with hands held together on the chest, as the wooden fish-shaped board is hit. Make a standing bow and send out the food." Quoted from: Enlightenment Unfolds, edited by Kazuaki Tanahashi, p. 252.

"The temple block comes from the East, particularly China, Japan, and Korea: in China it is called a muyu, in Japan a mokugyo, and in Korea a moktak. It is normally carved from camphor wood, is hollowed out in the centre, and has a horizontal slit, thus somewhat resembling the mouth of a fish. It is in fact sometimes known as the 'wooden fish,' and some temple blocks are ornately carved, the stem perhaps being shaped like a fish tail..." Quoted from: Practical Percussion: A Guide to the Instruments and Their Sources by James Holland, p. 50.

The image to the left is a detail from a triptych by Kuniyoshi now in the Lyon Collection. Click on the fish to see the whole thing. The photo shown above was posted at Flickr by Masaru Yoshiyama. |

|