|

JAPANESE PRINTS A MILLION QUESTIONS TWO MILLION MYSTERIES |

Ukiyo-e Prints浮世絵版画 |

||

| Kansas City, Missouri |

|

INDEX/GLOSSARY

Kara thru Ken'yakurei |

|

|

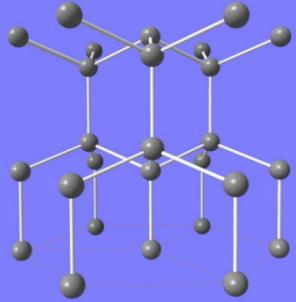

The molecular model on Lonsdaleite is being used as a marker for new additions from January 1 to May 31, 2021. |

|

|

|

TERMS FOUND ON THIS PAGE:

Kara,

Kara-kasa,

Karasu Tengu, Karazuri, Karigane, Kariginu, Kariyasu, Karuta-e, Karyōbinga, Kasa, Kasa, Kashirabori, Kashiwa, Kasuga Taisha, Katabami, Katabira Katagami, Kata-hazushi, Katakiuchi, Kataoka Nizaemon VIII, Katō mado, Katsuo, Katsuobushi, Katsura, Katsureki-mono, Katsushika Hokusai, Kawagoshi ninsoku, Kawakita, Kawarazaki Sanshō, Kawatake Mokuami, Kawatake Shinshichi, Kaya, Kayaribi, Kazaguruma,

Kazami, Kazashi, Kebori, Donald

Keene, Keian, Keichō,

Keisai Eisen, Keisei, Kemari, Kensaki, Kensaku and riken, Kentō and Ken'yakurei

空摺, 雁金, 狩衣, 刈安, 加留多絵, 迦陵頻伽, 傘, 笠, 頭彫, 柏, 春日大社, 酢漿草, 帷子, 斤田, 型紙, 片外し, 敵討ち, 片岡仁左衛門, 火頭窓, 鰹, 鰹節, 桂, 活歴物, 葛飾北斉, 川越し.人足た, 河原崎 三升, 河竹黙阿弥, 河竹新七, 蚊屋, 蚊遣り火, 風車, 汗衫, 翳, 毛彫,

慶安, 慶長,

剣先, 羂索 & 利剣 and 見当 |

|

|

|

One more note about this page and all of the others on this site: If two or more sources are cited they may be completely contradictory. I have made no attempt to referee these differences, but have simply repeated them for your edification or use. Quote anything you find here at your own risk and with a whole lot of salt. |

|

|

TERM/NAME |

KANJI/KANA |

DESCRIPTION/ DEFINITION/ CATEGORY Click on the yellow numbers to go to linked pages. |

|

Kara |

唐 から |

T'ang China and by extension China. In islation the character 唐 is pronounced tō. Ivan Morris wrote in The World of the Shining Prince: Court Life in Ancient Japan on page 8: "The prefix kara ('Chinese') in front of any object was invariably a mark fo elegance and value, like the word 'imported' in the more expensive shops of London and New York."

Kara-kasa is one such example - see the entry below. The umbrella was an ancient Chinese invention and was a marvel when it was first brought to Japan during the period or earlier. There is also the karaginu (唐衣) which is a short coat worn by noblewomen during the Nara and Heian Periods. |

|

Kara-kasa |

唐傘

からかさ |

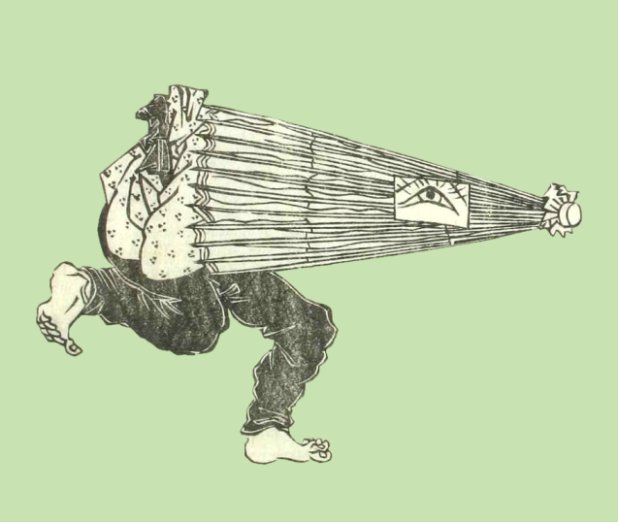

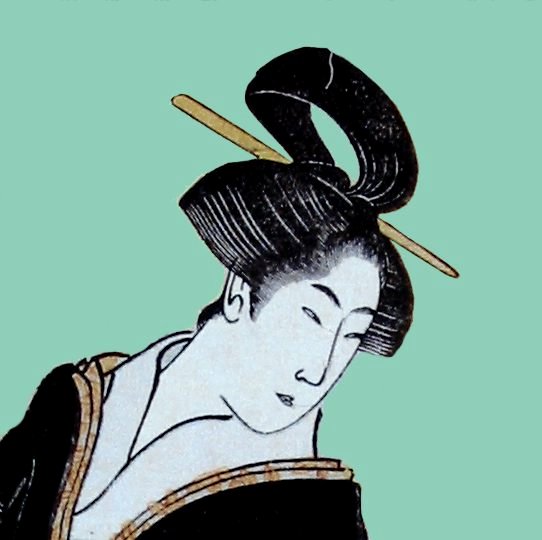

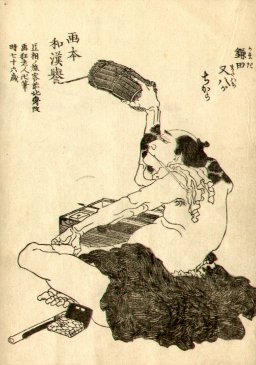

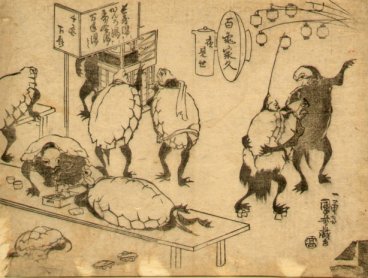

The print to the left shows the actor Arashi Sangorō III pretending to be an umbrella monster. The accompanying poem reads: "My flower umbrella/ tattered and worn/ in the guise of a monster!" Julia Meech wrote: "A one-legged umbrella monster with a long tongue appeared on the scene with the surge of ghost plays in the early 19th century.... The knee of Sangorō's retracted left left is just visible under the rim of the umbrella.... This umbrella demon has a depression on his head, suggesting that he is doubling as a kappa, another nasty goblin from Japanese folklore..." (Source and quotes from: Rain and Snow: The Umbrella in Japanese Art, by Julia Meech, Japan Society, Inc., 1993, cat. entry #92, p. 118)

The image shown above is a detail from a book illustration also by Toyokuni I.

In their authoritative book on surviving Japanese monsters Hiroko Yoda and Matt Alt have a whole section on the 'Haunted umbrella'. It is paired with the 'Haunted lantern' because they are often seen together. They are known for their "Freakishly large tongue... [and] Single gnarly leg..." Their "Offensive Weapons" are "Bronx cheers, eerie moans, [and] erratic movement." Their weakness: Being ignored. They hate that, but that is okay because they have very short attention spans. Also, there is no record of their ever having actually injuring or killing anyone.

"The most popular portrayal of the Kara-kasa, whose name simply means 'paper umbrella' or 'paper parasol,' is of a cyclopean umbrella with a lolling tongue and a gross-looking hairy male leg in place of a handle, but other versions - perhaps subspecies? - have been reported as well." Sometimes they have two eyes shown close together and sometimes just one. (Source and quotes: Yokai Attack! The Japanese Monster Survival Guide, by Hiroko Yoda and Matt Alt, Kodansha International, 2008, pp. 106-109)

Kara-kasa literally means 'paper umbrella'. |

|

|

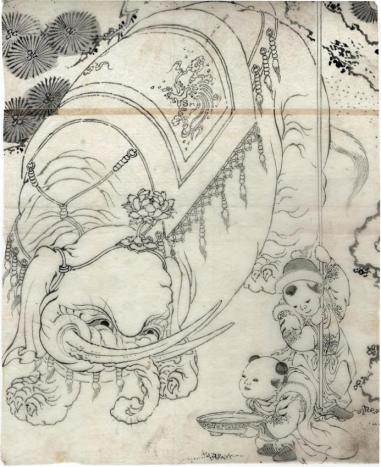

唐子

からこ |

Chinese children, almost always males, or Japanese children dressed up as Chinese children.

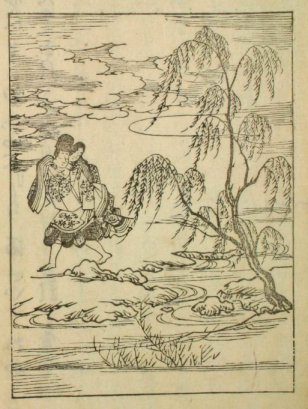

The image to the left is by Kiyonaga and is from the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Above is a preparatory sketch for an unknown woodblock. It comes from the Lyon Collection. |

|

Karakurenai |

韓紅

からくれない |

A deep red made from multiple dyeings - up to 8 times - using a pigment from safflower. During the Heian period the safflower may have come from China. Because safflower dye was as expensive as gold this color was 'kinjiki' (禁色) or forbidden for use by anyone but the highest court nobles.

“紅” is in the ancient reading of “kurenai”, but became a color name read as “beni” during the Edo period.

Two early poets, Ariwara Narihira (在原 業平: 825-880) and Ki no Tsurayuki (紀貫之: ca. 872-945), both made use of this term and its allusive powers.

Unheard of even in

Narihira

Wtih the passing years their color has been transformed into Chinese red - those tears that might once perhaps have been taken for white beads.

Tsurayuki |

|

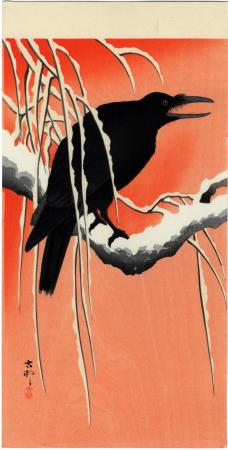

Karasu |

烏 からす |

Crow - This bird in Japan has many shades of significance. For instance, its croaking was thought to be an prediction of a fire when heard in the night. "Nevertheless the crow is a messenger to gods, more especially the gods of the temple of Kumano, where karasu is depicted many times over and were ravens have their nests in the trees, surrounding the temple. Legend has it that in ancient days the ravens of Kumano brought a kind of peacurd to the monks of Koyasan, who paid for it with small copper coins. Therefore ravens in general are thought to have supernatural power and are never molested." Quoted from: Animals in Far Eastern Art... by T. Volker, p. 39.

The image to the left is from the Lyon Collection. To see more about this print click on it. |

|

Karasu Tengu |

烏天狗

からすてんぐ |

A crow-billed goblin or tengu.

The image to the left was posted at commons.wikimedia by WolfgangMichel. |

|

Karazuri |

空摺 からずり |

Blind printing or embossing.

Von Seidlitz said that Shigenaga was the first to use blind printing in ca. 1730. |

|

Karigane |

雁金

かりがね

|

Wild geese crest or

mon: According to Merrily Baird the return of migrating geese was so

important that it gave its name to the 8th lunar month. This is not so odd

when one considers how the months and days got their names in the West.

Source: Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design, pp. 111-112.

John W. Dower (The Elements of Japanese Design pp. 94-5) that in some of the earliest depictions of flying geese in Japanese art a simple "v" was used. Later when geese were portrayed in crests the head was added. However, the form seen to the left is referred to as the "knotted goose". These two stylistic approaches were far more popular in the use of family mons than more realistic examples.

|

|

The other night - today is March 30, 2007 - I was reading Roger Keyes catalogue of the Osaka prints in the Philadelphia Museum of Art and ran across an entry about two death or memorial prints dedicated to the passing of a famous actor. One shows Utaemon IV accompanied by 'his farewell poem': "Returning geese, if you are going to the country of the west, please take me with you." Keyes notes that "Migrant geese often appear in memorial or farewell poems. The country of the west is Amida Buddha's Western Paradise."

Source and quote from: The Theatrical World of Osaka Prints, by Roger S. Keyes and Keiko Mizushima, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1973, p. 188.

That led me to dig a little deeper. I remembered a reference to bird dances from the Kojiki (古事記: 712), the most ancient Japanese text which portrays indigenous, non-Buddhist beliefs. "Bird bones have been found resting on the chests of ancient human skeltons, and the Kojiki alludes to a custom whereby mourners dress up as birds. The evidence suggests, then, that the ancient Japanese believed that the dead turned into birds, or perhaps birds carried them to another world."

Quote from: Japanese Death Poems: Written by Zen Monks and Haiku Poets on the Verge of Death, introduction and commentary by Yoel Hoffmann, Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1996, p. 34.

There is also a reference in the Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan (Vol. 3, p. 13 - entry by Saitō Shōji) which states that "In the reign of the legendary emperor Nintoku in the KOJIKI (712), there is an anecdote in which the laying of an egg by a goose was taken as an auspicious sign of the emperor's enduring rule. (Geese normally do not lay eggs during the season of their stay in Japan.)" Geese are also used as a poetical allusion to the coming of autumn.

The image to the left of flying geese is a detail from a print by Bunrei and was sent to us by our generous contributor E. Once again thanks E! |

||

|

|

||

|

Kariginu |

狩衣 かりぎぬ |

Kariginu - "informal clothes worn by the nobility from the Heian period onwards". |

|

Later in the Heian period, noblemen adapted working-class men's clothing style. Their pants were tied around the ankles for ease of movement. The nobleman's outer robe became the sporty and informal kariginu. a belted hunting (kari) robe (ginu) with unsewn sides, upper shoulder seams, and cords to tighten the sleeve openings. These features allowed greater mobility..." Quoted from: The Kimono Inspiration: Art and Art-to-wear in America, p. 138.

In the Historical Dictionary of Shinto by Picken it says on page 154: "Most of the liturgical vestments of modern Shinto clergy were developed in the Heian period (794–1185), modeled on the court dress of T'ang Dynasty China (618–907). The kariginu originated as a hunting garment worn by nobles and soldiers. The shaku, a flat wooden scepter, was used in the T'ang court as a memo pad, but is now carried by priests as a symbol of office."

As part of the formal abdication ceremony the emperor would change out of court robes into a kariginu.

"For summer wear the kariginu was of thin unlined silk, but for winter use it was lined. There were no strict rules as to colour or pattern, but old men generally wore white, while for those below the fifth rank the kariginu was patternless and was then known as hoi (or hōi)." Quoted from: Publication: Victoria and Albert Museum, Issue 120, p. 37.

"Court servants wore a sort of kariginu of starched white calico, known as shirahari or hakucho. It had no running-strings on the sleeves. Their sashinuki trousers, also white, reached to the knee only, and below them leggings (kiahan) were sometimes worn; their unsocked feet were shod with sandals (zori) for outdoor use. They wore no sword." Ibid., p. 38

"Kariginu was worn in all four seasons. There were several differences in its substance according to the ages of the wearers. Above the fifth rank it had lining, and below the sixth rank it was called Nuno-Kariginu, or grass cloth, and the silk fabric or the kind of gauze was never worn. Obi or girdle of Nuno-Kariginu was a piece of cloth used in Shita-gasane. Above the third rank it was a silk damask of Suo-no-Sudzushi (a kind of damask) in summer, and in winter it was a white silk Fusencho damask. Below the fourth rank it was of pure blue, and made of the woven cloth called Komeori in summer, and in winter its outer surface was white, and the lining black , &c. In white Kariginu the black cloth was made its outer surface, which change was called turning the girdle. All these kinds of Kariginu had a Sode-Kukuri, or sleeve binder, which also differed in its substance according to the age of the wearer in the same way as Konaoshi." Quoted from: The Health Exhibition Literature, 1884, p. 606. |

||

|

|

||

|

Kariyasu |

刈安

かりやす

|

Kariyasu or Miscanthus tinctorius: This is one of the plants - a grass, in fact - used to create a yellow colorant in dyeing fabrics. Apparently it was also used in printing woodblock images although none of the contemporary books on technique seem to make references to it. Perhaps this is due to the fact that this was one of the colors which faded greatly and therefore would not be part of the palette of modern printers. However, it is mentioned in Japanese Woodblock Prints: A Catalogue of the Mary A. Ainsworth Collection by Roger Keyes as one of the early traditional organic colorants. (cf. "Identification of Traditional Organic Colorants Employed in Japanese Prints and Determination of their Rates of Fading" by Feller, Curran and Bailie - pp. 253-261.)

Miscanthus tinctorius is a tall grass which grows on the slopes of mountains. These images taken by Shu Suehiro were from his hike on Happō One Mountain in the Japanese Alps not far from Nagano. A popular ski area in the winter it is considered a great hiking region during warmer months.

According to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston this yellow "...dye is primarily composed of anthraxin and related flavonoids..." which are mainly luteolin glycosides. They also note that when the mordant is alum this colorant is not very lightfast. Perhaps that is why it is so difficult for us today to identify this colorant in early prints. Hence, luteolin is the main colorant.

When fresh, I believe, this dye can be a bright yellow. When mixed with other dyes everything from mustard yellow to a moss green can be produced.

In an article by Watanabe Hitoshi and Takahashi Yasuhiro published in the "Bulletin of Japan Association of Botanical Gardens" in 2006 they stated that "...the true M. tinctorius population is very small.... The length of beard at the tip of the spikelet and the density of down on the leaf blade are the most important features" The spikes are discarded and only the stem and leaves are used [in creating the dye.] The harvest should be dried quickly before soft, ground water with the least number of impurities is added. Camellia ash helps bring out the brightest color.

Shu Suehiro has very generously given us permission to use the three photos to the left. He operates a wonderful and expansive web site dedicated to Japanese plants. We would urge you to take a look. There is much of interest there.

http://www.botanic.jp/index.htm

Don't forget that color descriptions are not exact. As there are many shades of green or blue for example, there are many slight variations within each of the colors shown here which may or may not conform precisely to your own perceptions of what they should be. Several sources have said that kariyasu is the color of a Buddhist monk's 'safron' robe. That is why we are posting the photo below. It is greatly cropped from an image posted at commons.wikimedia.org. by MichaelJanich.

|

|

Karuta-e |

加留多絵

かるたえ |

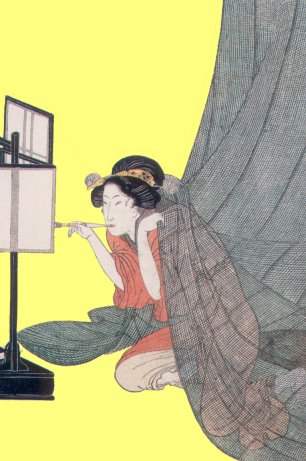

Playing card picture(s): The image to the left is by Shunsho (春章) and Shigemasa (重政) from the 1776 edition of the "Seiro bijin awase sugata kagami" (青楼美人合姿鏡).

This image was generously contributed to our site by E. Thanks E!

|

|

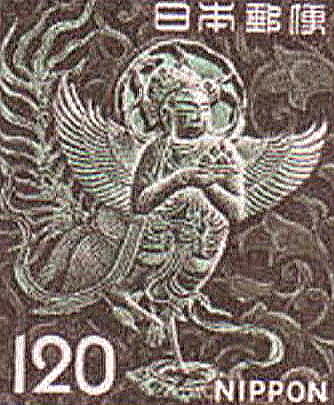

Karyōbinga |

迦陵頻伽 (?)

かりょうびんが |

A heavenly singer. Half-bird, half-human. Its voice is likened to that of the Buddha. In Royall Tyler's translation of "The Tale of Genji" (vol. 1, chap. 7, p. 135 Genji's voice is praised 'to the heavens': "His singing of the verse could have been the Lord Buddha's kalavinka voice in paradise." It brought the emperor to tears. Arthur Waley in his translation (p. 150) states: "...and in the song which follows, the first movement of the dance his voice was sweet as that of Kalavinka whose music is Buddha's law." Seidensticker (p. 140) said that Genji's audience "...could have believed they were listening to the Kalavinka bird of paradise." |

|

The karyōbinga is the Japanese name of the kalavinka, i.e., the bird which sings in paradise. Long before the introduction of Buddhism the Japanese had a traditional lore devoted to human/bird hybrids. They appear in the Kojiki which is the earliest written account of Japan's distant past.

As of now we don't have an example of a karyōbinga in an ukiyo print which we can display here, but we are almost positive we have seen one somewhere. If anyone can help us in this search please contact us.

We know such a thing exists because there is a hand-colored print by Torii Kiyomasu I in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts with a karyōbinga. Dated from the first decade of the 18th century it illustrates a scene from a kabuki play "The Treasure Boat of the Land of Brahma" (Bontenkoku takarabune - 梵天国宝船). Remember - many early kabuki plays had a strong religious element to them and that this figure is not to be confused with other bird-men (or -women, if you like.) |

||

|

|

||

|

Kasa |

傘

かさ |

An umbrella

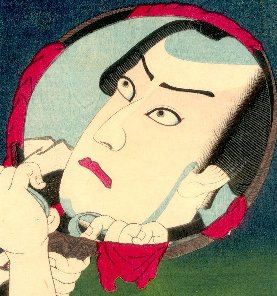

The image to the left shows the underside of an umbrella. We found it at commons.wikimedia. The Kunisada print shown above is from the Lyon Collection. To see a larger image click on it. |

|

Kasa |

笠

かさ |

(Bamboo) hat: "The sedge hat had patrician rather than peasant association in traditional Japan, and thus it was not anomalous that the haughty upper classes developed this as a design."

Quoted from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 114.

Either kasa or amagasa (雨笠) may be used to mean rain hat. Since kasa was a homophone for the word for syphilis, leprosy, a boil or skin eruption (瘡). For this reason rain hats became inextricably linked to certain afflictions like smallpox and also socially transmitted diseases. Straw hats became a symbol of divine protection. "Children were to begin wearing these hats before catching smallpox. Motoori Norinaga 本居宣長 (1730-1801), too, refers to this protective hat in his Kojiki den 古事記伝. He notes that someone who prays for a benign case of smallpox should go to the shrine of Sagi dymyōjin and borrow a bamboo hat, which is to be placed and honored in the house. Once recovered, the person is to make a second hat and to return it to the shrine with the first. Others will then borrow it in turn. That is why hats accumulate at the shrine."

Quoted from: "Demonic Affliction or Contagious Disease?: Changing Perceptions of Smallpox in the Late Edo Period", by Hartmut O. Rotermund, published in the Japanese Journal of Religious Studies, 2001, vol. 28/3–4, p. 378. |

|

Kashirabori |

頭彫 かしらぼり |

Head carver: "There were two categories of carvers, the kashirabori (literally carvers of the head) and the dōbori (carvers of the body). The kashirabori were the most highly skilled and had overall responsibility for the blocks and would hand out work to the dōbori in line with their abilities."

Source: Japanese Woodblock Printing, by Rebecca Salter, University of Hawai'i Press, 2001, p. 61.

For more information see also our entry on menbori. Like the term menbori there are very few references to kashirabori in English. |

|

Kashiwa |

柏

かしわ |

The oak leaf was once used as a surface for offerings to the gods. "By the late Heian period, the oak tree was regarded as the residence of the protective deities of forests and groves. This was one of the more popular crests among the warrior class, particularly among close devotees of Shinto."

Quoted from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 114.

Remember there are numerous other variations on this motif which were used as crests or mons. |

|

Kasuga Taisha |

春日大社

かすがたいしゃ |

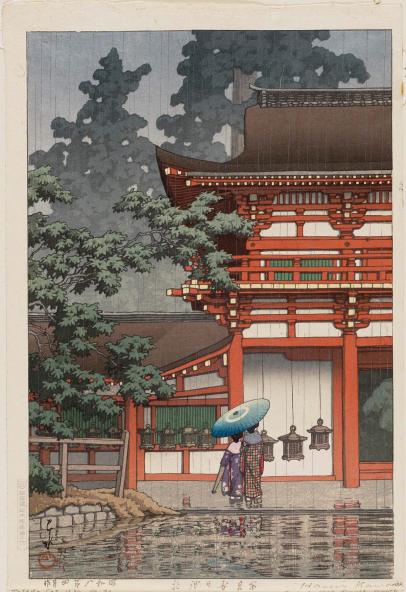

The Kasuga Grand Shrine in Nara - According to legend the god Takemikazuchi no Mikoto rode a deer from Kashima to the Kasuga forest and thus was the beginnings of the sacred nature of these shrine grounds. This is also the source of reverence for deer at this shrine, because they are thought to be the messengers of the gods.

The image shown above is from a 1921 print by Hasui at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The photo to the left was found at Wikipedia Commons where it was posted by nnh. |

|

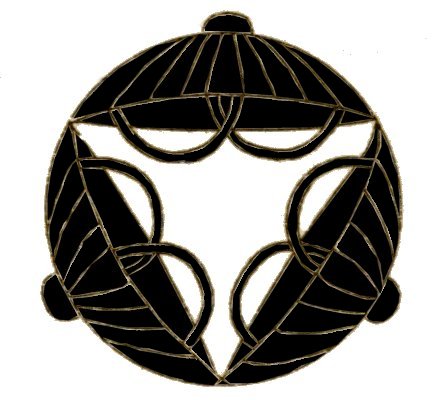

Katabami |

かたばみ

|

The oxalis or wood sorrel: "In the early days in Japan, the leaf of the wood sorrel was used to make a medicinal salve, and also to polish mirrors." Popular as a design during the Heian period it was often later used by member of the warrior class. Because the plant spread prodigiously warriors saw this as an auspicious sign of their own fertility. An added martial element to the katabami mon or crest was the insertion of blades radiating outward as in the example to the left.

Source and quote from: The Elements of Japanese Design, by John W. Dower, p. 84.

Remember there are numerous other variations on this motif which were used as crests or mons.

The image to the left on the bottom is shown courtesy of Paghat the Ratgirl who offers a wonderful and literate web site about plants - and so much more. Do yourself a favor and visit it often at: http://www.paghat.com/gardenhome.html

When swords are added to katabami motif the pattern is referred to as the ken-katabami (剣酢漿草) or 'sword katabami'.

On 10.12.19 we discovered that we had erroneously listed this entry as 酢奨草. This was a mistake and we apologize. We corrected our mistake and changed it to 酢漿草.

Above is a detail from the roof at Himeji Castle. |

|

Katabira |

帷子 かたびら |

"...unlined fabric of asa-hemp." Source: Karen Mack

For more information go to our entry on yukata. |

|

Katada Hori Chō (aka Katada Chojirō) |

斤田

かただ.ほり.ちょう |

Master carver of woodblocks working in the early 1860s to as late as 1878. We know that he worked for more than one publisher: Kakumotoya Kinjirō, Izutsuya, Iseya Zenazburō, Etsuka, Tsunoi and Arai Kisaburō. His seal appears on prints of Toyokuni III, Kunichika and Chikuyo. |

|

Katagami |

型紙

かたがみ

|

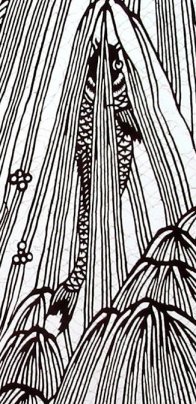

Literally 'paper pattern': Mulberry paper specially treated with astringent persimmon juice cut into intricate and delicate patterns to be used as stencils for fabric designs. Known since the 12th century these stencils were used to produce katazome. Ukiyo prints are rife with such dye-resist kimonos.

To the left are the cover (below) of Carved Paper: The Art of Japanese Stencil, the best book on the subject out there in English. (Edited by Susan Shin-Tsu Tai with contributions by Susanna Campbell Kuo, Richard L. Wilson and Thomas S. Michie, published by the Santa Barbara Museum of Art and Weatherhill, Inc., 1998)

The top image is a detail of the leaping fish on the cover. Notice the fine threads which help hold the delicate design together. Some katagami have such threads and some do not.

|

|

Kata-hazushi |

片外し

かたはずし |

A hairstyle of a palace servant.

At various times sumptuary laws were enacted by the ruling powers in an attempt to control social behavior. This extended to artists and their publishers and pretty much everyone else. Certain images were proscribed and it became a battle of wills as to who could outwit whom. In The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro (text volume, p. 247) Timothy Clark (ティモシー .クラーク) commented on this by addressing the subject of altered forms.

One Utamaro print clearly shows a woman wearing a kata-hazushi hairstyle. A different, but still original printing show another hairstyle.

"A second printing exists in which the head area of the block has been plugged and recarved with a normal Katsuyama-style hair-do... Perhaps this was done to avoid any possible censure from the authorities for showing a hair-style immediately associated with a samurai household."

The detail to the left is not one of those Utamaro examples, but is from a print by Toyokuni I. |

|

Katakiuchi |

敵討ち

かたきうち |

Revenge, vengeance - "On the seventh day of the second month of 1873, less than five years after the Meiji restoration, Justice Minister Shimpei Eto decreed blood revenge illegal and ended the practice of katakiuchi (blood revenge).... Until this time, however, for almost a millenia revenge held an honored place in Japanese culture..." Quoted from: Revenge Drama in European Renaissance and Japanese Theatre: From Hamlet to Madame Butterfly by Kevin J. Wetmore, p. 6

"In her seminal study of Japanese culture, The Chrysanthemum and the Sword, Ruth Benedict dedicates a significant portion of the text to the study of debt and obligation in Japanese society, observing that revenge is a kind of giri, meaning a debt that can and must be repaid. Katakiuchi was strongly regulated by the bakufu. The right of revenge, with the unwritten caveat that the intended victim of revenge also not be someone of value to the bakufu, was only granted when one's lineal forbear (or feudal lord) had been murdered and the killer had escaped justice. Ikegami Eiko also lists two reasons for private (unauthorized) revenge: burei-uchi (disrespect killing), which is the killing of a commoner by a samurai for disrespectful behavior—'a collective defense of the honor of the samurai class.' Second is megataki-uchi (wife revenge), the killing of an unfaithful wife and her lover by a wronged husband (women did not have this right; husbands could cheat without fear of revenge—at least not socially sanctioned revenge). ¶ Registered revenge, however, remained the feudal ideal. It consisted of a series of steps and was extended even to peasants Ikegami traces the steps of the process: First, the wronged individual petitions his daimyō for permission to revenge. Then, the daimyō submits the names of the revenger and the intended victim to the Shogun, who has them placed on a list along with the names of sukedachi (assistant avengers), who also had to be registered. A copy of the written permission is given to the avenger, who may then find and kill his intended victim. Upon completion, the revenger reports his success to the shogunate. No counter-revenge could be taken by the victim's relatives or retainers against the avenger, and justice was considered done and the matter closed. A successful avenger was honored and praised, but one who had not completed his revenge for whatever reason had no status and could not return home. As Ikegami reports , registered revenge allowed the Shogunate to 'present themselves as the official guardians of the samurai's honorable spirit while controlling and normalizing its violent content.' " (Ibid., pp. 6-7)

To the left is a print by Yoshitoshi called 'The Widow's Revenge'. |

|

Kataoka Nizaemon VIII |

片岡仁左衛門 かたおか.にざえもん |

Nizaemon VIII (1810-63) was born in Echigo (越後) and began his acting life as Ichikawa Shinnojō (市川新之丞), the adopted son of Ichikawa Danjūrō VII. He became the manager of a theater or zamoto (座元) in Osaka specializing in children's kabuki or kodomo shibai (子供芝居). After Shinnojō/Nizaemon had a falling out with his adoptive father he changed his name to Mimasu Iwagorō (三枡岩五郎). When he became a pupil of Arashi Rikan II Iwagorō took the new name of Arashi Kitsujirō (嵐橘次郎). While studying with Rikan II Kitsujirō learned how to perform outside of shrines and temples. When Nizaemon VII adopted him Kitsujirō changed his name again in the 4th month of 1833 to Kataoka Gatō I (片岡我当). Nizaemon VII died in 1837. At that time in the 8th month Gatō took his adoptive father's haiku writing pen-name or haimyō (がごう). Now he was called Kataoka Gadō II (片岡我童). (Professor Leiter notes that "...a different sequence of ordinal numbers is used for bearers of the haimyō.") He came to be regarded as one of the great performers of leading male roles. In 1854 he joined the Nakamura-za in Edo and three years later in the first day of the 4th month of 1857 he changed his name to Nizaemon VIII. "Since his good looks resembled those of the immensely popular Danjūrō VIII, he was almost as popular in Edo as in Kamigata. After eight years away, he returned to Osaka in 1862, dying there a year later." (Leiter, p. 297) Although he played a full range of roles Leiter says he was most successful as a handsome young lover. Two of his own sons and one who he adopted all became successors to the name Nizaemon. ¶ We know that he was the subject of prints by Hirosada, Toyokuni III, Yoshitsuya, Hirokane, Yoshikuni and Kunisada II. Click on the image above to see the full unaltered print. |

|

Katō mado |

火頭窓

かとうまど |

A cusped, bell-shaped window: "The form of the flame-shaped window, katō-mado (literally, firelight window), which is also called andon-mado, is almost alien to the whole composition of rectangular planes, linear construction, and geometrically simple forms, and suggests that its major function is of a decorative nature. It is a rather common sight in shrines and temples, while its use in the residence is confined to the wealthier class who can afford to accentuate the place of the picture recess, tokonoma, by an ornamental window and a more effective light source than could be provided by a sliding door, shoji." Quoted from: Measure and Construction of the Japanese House by Heino Engel, p. 124.

In the Castles of the Samurai: Power and Beauty (p. 102) it says that this style of window was introduced from China in the 13th century.

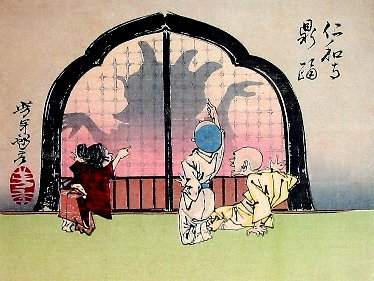

The image to the left is from a print by Yoshitoshi. Ignore the figues and the silhouette and concentrate on the shape of the window. |

|

Katsuo |

鰹 かつお |

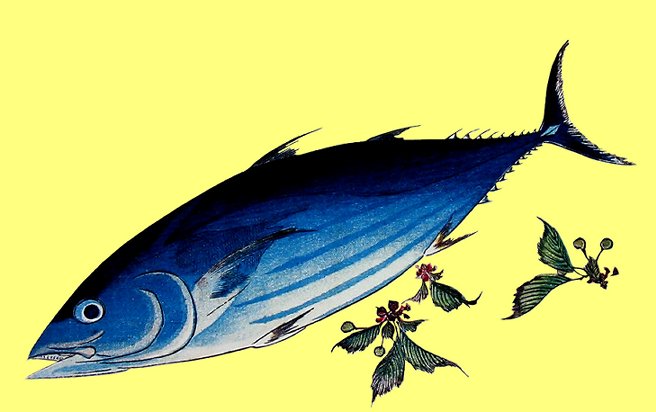

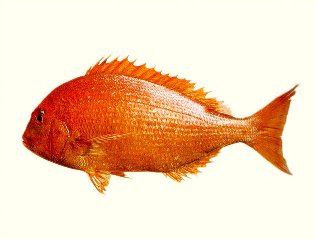

Bonito: Katsuwonus pelamis - also known as the skipjack tuna, et al. It was formerly called the Euthynnus pelamys.

The detail above is our adulterated image from a print by Hiroshige. |

|

When Edward Strange wrote about the original print by Hiroshige in 1925 he identified the plants floating near the fish as being cherries. However, this appears to be a mistake. In the unadulterated version of this print there are two poems printed above the fish. One reads:

Fresh bonito taste best when you let it melt in your mouth under the snow of Kamakura.

"The name of the flower depicted here means literally 'under the snow'." That flower is the saxifrage. (Source and quotes: Hiroshige: Prints and Drawings by Matthi Forrer, cat. entry #84)

This is a minor point, but a great quote from page 8 of Yoshiwara: The Pleasure Quarters of Old Tokyo by Ethel and Stephen Longstreet which makes mention of bonito. "The Americans, being sinning males, soon became well acquainted with the famed geisha and courtesan houses along the river Sumida. A geisha party that meant soft glow from many-colored lanterns, the dissonant sounds of the samisen, a mossy garden with elegant trees, a banquet with pickled sea urchin eggs, green tea, dried seaweed, bonito entrails, mushrooms and cuttlefish served with maple leaves and chrysanthemums."

Below is a photo of a Katsuwonu pelamis caught off the coast of Java. It was posted at commons.wikimedia.org by Wibowo Djatmiko.

|

||

|

|

||

|

Katsuobushi |

鰹節

かつおぶし |

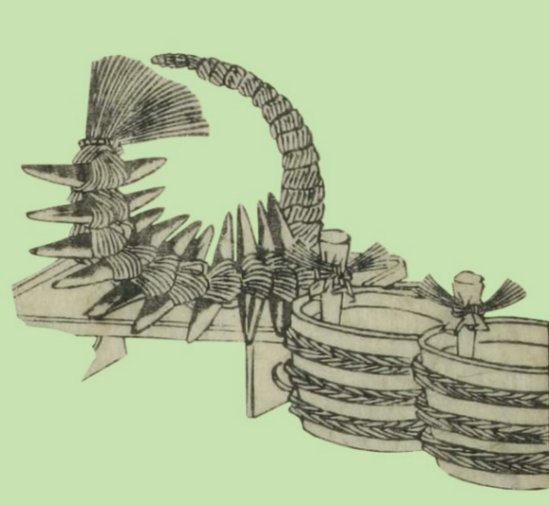

Dried bonito. The image to the left (by Kunisada) shows these dried pieces of fish incorporated into a woven wreath. 1

The image above is by Toyokuni I.

Donald Keene quotes a senryū, normally a comic poetic form, with a poignant messge.: "Stuck in his sleeve/ When he goes begging for milk,/ A dried bonito". Keene interprets this as a father with a new born whose mother died in childbirth. In exchange for the milk he is ready to present them with a dried bonito. (Source and quote: World Within Walls, by Donald Keene, Holt, Rheinhart and Winston, 1976, p. 531) |

|

"Smoked and dried, katsuo bushi, it is given as a present at weddings, births and other family feasts. For katsu also means to win and katsuo, success in life." Quoted from: The Animal in Far Eastern Art: And Especially in the Art of the Japanese Netsuke, with References to Chinese Origins, Traditions, Legends, and Art by T. Volker, p. 21. |

||

|

|

||

|

Katsura |

桂

かつら |

One of several woods like hōnoki and yamazakura used to print woodblocks. This type is often used in modern printmaking. 1 |

|

Katsureki-mono |

活歴物 かつれきもの |

Kabuki's 'living history plays' 1 |

|

Katsushika Hokusai |

葛飾北斉

かつしか.ほくさい |

Major 19th c. artist (1760-1849). He was said to have moved at least 93 times in his life and was said to have changed his name more than any other artist. "In his 60s, he adopted the name Iitsu, which some scholars translate as “one year old again.” " According to a March 18, 2015 article in the Wall Street Journal, even though Hokusai was well known in Japan some people believe he took on he job of producing images of Mt. Fuji to help pay off a gambling debt incurred by his grandson.

Hokusai was not much of a braggart. He felt that he had produced something good when he created 'The Great Wave' after he turned 70. He said that everything created before that was "not worth bothering with." Of course we disagree. Yet he wrote: “At 75 I’ll have learned something of the pattern of nature, of animals, of plants, of trees, birds, fish and insects. When I am 80 you will see real progress. At 90 I shall have cut my way deeply into the mystery of life itself. At 100, I shall be a marvelous artist. At 110, everything I create; a dot, a line, will jump to life as never before.”

The image to the left was sent to us by our generous correspondent E. and is one of that collector's favorite images. Thanks E! 1 |

|

Kawagoshi ninsoku |

川越し.人足た かわごし.にんそく |

The men who carry travelers across a river. "The Tokugawa government infamously maintained a ban on the construction of bridges over major rivers for purposes of defense. At such places “river-crossing men" (kawagoshi ninsoku [川越し人足]) were stationed to carry travelers and their luggage, either on their shoulders or on carrying boards. The Ōi River was regarded as the most difficult spot to cross along Japan's main artery at the time, the Tōkaidō Road." Quoted from: Japanese Women Poets: An Anthology by Hiroaki Sato.

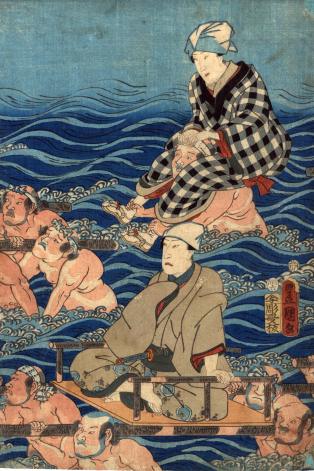

The image to the left is one panel of five by Toyokuni III showing actors being conveyed across the Ōi River. To see the full composition at the Lyon Collection click on the image. |

|

Kawakita |

かわきた |

A village where a special kind of ganpi was made. 1 |

|

Kawarazaki Sanshō |

河原崎 三升

かわらざき.さんしょう |

Kabuki actor (1839-1903). |

|

Kawatake Mokuami |

河竹黙阿弥 かわたけ.もくあみ |

Kabuki playwright 1816-93 1 His poetry name was Juami Kisui. |

|

Kawatake Shinshichi |

河竹新七 かわたけ.しんしち |

(See above) A name used by Mokuami until 1880. 1 |

|

Kaya |

蚊屋 or 蚊帳

かや |

Mosquito net: There is a small but beautiful group of three prints by Utamaro each showing two women, one under or behind mosquito netting and the other nearby just outside of it, dating from ca. 1794-5. Inspired either by Utamaro or his publisher Tsutaya these prints are remarkable examples of the carver's and printer's art. Poetically entitled "Woven in Mist" or kasumi-ori (靄織) the name captures it all. (Actually the full title is "Model Young Women Woven in the Mist", but I think you get my point.)

The detail from the print to the left is not by Utamaro but by Kunisada created several decades later. Nevertheless, this image makes it clear how refined the representation of the mundane could be even in woodblock form.

Source: The Passionate Art of Kitagawa Utamaro, published by the British Museum Press, London, 1995, Text volume, p. 149.

We have added a more extensive entry on kaya to our new blog site. It is dated May 15, 2009. If you would like to read more than please visit it at https://printsofjapan.wordpress.com/?s=kaya. |

|

Kayaribi |

蚊遣り火 かやりび |

Smoky fire to repel mosquitoes. Below is a Kuniyoshi print from a filial piety series. The boy has started a smoky fire to keep mosquitoes away from his father.

|

|

Kazaguruma |

風車

かざぐるま |

Pinwheel (of windmill): One type of clematis is given this name because of its resemblance to pinwheels. Also, one source says that there is a slang term, kazaguruma, referring to a policeman who only circles high crime areas.

Ōkuma Kotomichi (大隈言道: 1798-1866) wrote poems about children. At least one included a kazaguruma.

Sleeping on the mother's back the pinwheel spins even in the baby's unconscious hand.

Quoted from: Early Modern Japanese Literature: An Anthology, 1600-1900, edited by Haruo Shirane, translated by Peter Flueckiger, pp. 958-9.

The text reads: いもが背にねぶるわらはのうつつなき手にさへめぐる風車かな

Kazaguruma

imo ga se ni neburu warawa no utsutsu naki te ni sae meguru kazaguruma

"In Japan, the wind-mill is a common toy, and is made of paper vanes fastened on slips of bamboo, which are arranged like the spokes of a wheel. The vanes are usually alternately red and white, or other colors. It is commonly called kazaguruma (wind-mill), and sometimes hanaguruma (flower-mill), the latter name being applied to a special kind." (Quoted from: Korean Games with Notes On the Corresponding Games of China and Japan by Stewart Culin, p. 22) |

|

Kazami |

汗衫

かざみ |

A formal type of Heian court clothing for women. The character 汗 or ase means sweat or perspiration.

The image to the left was sent to us by E. our wonderful contributor. It is a detail from a 1789 book illustration by Shunsho portraying a Heian poetess in kazami garb.

Thanks E! |

|

Kazashi |

翳 かざし |

While doing

research on Japanese fans I ran across a reference to the kazashi

which I thought was too good to pass up. U. A. Casal in his

"Lore of the Japanese Fan" (Monumenta Nipponica, vol.

16, no. 1/2, 1960, p. 94) wrote: We may note that long into historical

timer; the nobles of Japan used a so-called kazashi", a fan-shaped object

with a long handle, to

For more information in general on fans see our entries on ōgi and uchiwa. |

|

Kebori |

毛彫 けばり |

Hair ( or hair line) carving: Some sources state that it takes the most experienced carvers to create the fine hairs seen in some prints. It is far too difficult for beginners. Only a master can do this. The lines had to be cut in a precise, but not boring way.

This term is also applied to metal work carving techniques. In this case skill and uniformity count a great deal, but some experts say kebori is not the most important or difficult form of engraving.

Note: I have no idea why, but kebori, written with the same characters, can mean 'fishing lure or fly'. |

|

Keene, Donald |

ドナルド・キーン |

Contemporary expert on Japanese literature and culture. 1, 2 |

|

Keian |

慶安 けいあん |

The reign period from 1648-52 "...marked an end to overt 'Guerilla' activities (whether by rōnin or Christians), and the consolidation of feudal institutions. The genre/ukiyo-e style reached its culmination in painting, and began to spread its influence more widely in printed book illustration as well." Quoted from: "Historical Eras in Ukiyo-e" by Richard Lane in Ukiyo-e Studies and Pleasures, Society for Japanese Arts and Crafts, the Hague, 1978, p. 27.

Above is a woodblock printed image and text from this period, 1651, to be exact. We are not showing it because of its aesthetic qualities but as an example of what was being printed at this time. |

|

Keichō |

慶長

けいちょう |

The name of one of the reign periods, nengō, 1596-1615. This ear "...marked both the peak of the Momoyama Period in Kyoto and the commencement of the Edo period, with the new city of Edo (Tokyo) as the political capital. The nation was unified by the Tokugawa Clan and urban culture took strong root, Kabuki and jōruri drama began to flourish, and the courtesan quarter in Kyoto came to form a center of upper-class social and cultural life in that ancient city. During Keichō the amorphous Tosa and Kanō genre styles first began to develop in the direction of ukiyo-e, and printed book illustrations in Japanese style was introduced. Within a generation these two forces were to combine to create the first ukiyo-e in printed form." Quoted from: "Historical Eras in Ukiyo-e" by Richard Lane in Ukiyo-e Studies and Pleasures, Society for Japanese Arts and Crafts, the Hague, 1978, p. 27.

The image to the left is from the 1608 edition of the Tale of Ise (伊勢物語). The scene represents the Akutagawa elopement passage. |

|

Keikikyū |

軽気球

けいききゅう |

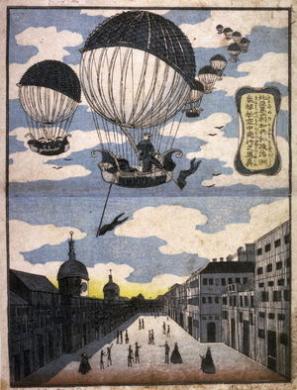

A dirigible -

The image shown above is an 1865 Yoshitora triptych. The 1861 Yoshitora print to the left is in the collection of the Achenbach Foundation. |

|

Keisai Eisen |

渓斎英泉 けいさい.えいせん |

|

|

"A popular and prolific

painter, book illustrator, and designer of ukiyo-e woodblock prints; a

playwright, novelist, biographer, and amateur historian. Real name Ikeda

Yoshinobu. Eisen was born in... Edo... the son of Ikeda Yoshiharu, a poet,

calligrapher, and devotee of the tea ceremony. His earliest works are

thought to be two illustrated novelettes published in 1808 and 1809 signed

Keisai Shōsen [

Source and quotes from: Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan, entry by Roger Keyes, vol. 4, pp. 189-90.

"A new style emerges in Kunisada's beauty prints following his return to Edo. The 1823 triptych Morning After Snow is an example. The rounded, elegant quality that distinguished his earlier prints has given way to an angular, sharp-edged line, Suzuki Jūzō suggests that Keisai Eisen... a student of Eizan, was the artist who initiated this change."

Quoted from: Kunisada's World, by Sebastian Izzard, Japan Society, Inc., 1993, p. 26.

The first use of Prussian blue on oban prints of women may have been on those of Eisen in ca. 1830. See our aizuri-e entry on our first index/glossary page.

Ibid, p. 29.

"Eisen... began to design his typical standing courtesans in a bout 1821 and the curves of Eizan gave way to compositions made up of short straight lines showing the increasingly stooping, 'hunchbacked' women, who all seem to be in the grip of intense emotion. In 1823 for three or four years he started to produce some striking half-length portraits of geisha... In 1829 he started quite a vogue by designing prints coloured almost entirely in different shades of berorin, a new, blue pigment. These are known as aizuri-e. His pupil Teisei Sencho continued to produce prints of courtesans in the same style and Eisen became increasingly involved in landscape prints... and kacho-ga [i.e., bird and flower pictures]..."

Quote from: The Art of Japanese Prints, by Richard Illing, published by Gallery Books, 1983, p. 82.

"Eisen... is less well known as a designer of kacho-ga but his working this field shows a sensitive artistic talent and can well stand comparison with his more famous contemporaries."

Ibid., p. 106.

Eisen was one of the artist who illustrated the first four of eighteen volumes of the Iroha Bunko (いろは文庫) by Tamenaga Shunsui (1790-1843: 為永春水), originally published in 1842. ¶ He also worked with Takizawa Bakin (1767-1848: 滝沢馬琴) in 1823, 27 and 41 on his 'Biographies of the Eight Dog Heroes' or Nansō Satomi Hakkenden (南総里見八犬伝) and on numerous other occasions. . ¶ Ryūtei Tanehiko (1783-1842: 柳亭種彦) was another one of the famous Japanese writers he worked with. And there were many more. |

||

|

|

||

|

Keisei |

傾城 けいせい |

"In the early Edo period, a popular epithet for these high-class courtesans was keisei (castle topplers.) Originating in China in the Han dynasty, the term referred generally to a beautiful woman, not a courtesan. The origin of the word is traditionally associated with a favorite subject of Emperor Wu of the Han, a handsome young man named Li. One day Li danced for the emperor, singing, 'In the north, there is a beauty peerless in the world. With one gaze, she topples a man's castle, with another gaze, she overthrows a man's kingdom.' Intrigued, the emperor asked whether such a woman really existed and found that Li was singing about his own sister. Upon summoning Li's sister, Emperor Wu indeed found her more than enchanting. Madame Li is not reputed to have toppled Wu's castle or kingdom, but other beauties are credited with bringing down dynasties by bewitching their enfeebled emperors, including descendants of Emperor Wu. In Japn the term 'castle toppler' was being used to refer to courtesans by the twelfth century." Quoted from: Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan by Cecilia Segawa Seigle, p. 36.

Several dictionaries translate keisei as beauty or siren. They also give it as prostitute or courtesan. |

|

Kemari |

蹴鞠

けまり |

An ancient ball game akin to hacky-sack in which a small group of noblemen attempt to keep a ball in the air for the longest time. It originated in China and was first mentioned in ca. 720 in the Nihon Shoki. The field was a small area bounded by trees and the ball was covered in deerskin. Soccer players practice similar moves among themselves as warm up exercises.

Lea Baten in her Playthings and Pastimes in Japanese Prints (p. 138) notes that there were two versions of this 'game'. In the other one "...a leather ball, stuffed with horsehair and shaped like two flattened ball halves sewn together, was kicked between goalposts of flowering trees."

The image to the left is a detail from a print by Chikanobu. It was sent to us by our generous contributor Eikei (英渓). Thanks Eikei!

"Les Japonais de l'époque de Heian pratiquaient également un jeu de ballon appelé kemari, ce qui signifie « balle au pied ». On délimitait pour ce jeu un terrain dans le jardin, à l'écart des bâtiments : quatre arbres d'essences différentes, espacés de six ou sept mètres, étaient plantés en carré : un pin, un prunier, un saule et un cerisier (arbres qui pouvaient être remplacés par des repères). Les arbres-repères devaient mesurer au moins quatre mètres cinquante - hauteur à laquelle devait être envoyée la balle - et leurs branches les plus basses se trouver un peu au dessus du niveau de la coiffure des joueurs qui étaient vêtus du « vêtement de chasse », utilisé pour l'exercice, et coiffés d'une bonnet. Le terrain était débarrassé de ses cailloux et aplani à l'aide de sel et de sable. (On le protégeait après le jeu en le couvrant de nattes.) Les participants étaient répartis en trois catégories : joueurs, assistants et arbitres. Au nombre de huit, les joueurs se répartissaient par paires au pied de chaque arbre. Les assistants (un par joueur) étaient chargés de ramener les balles égarées. Les arbitres choisis parmi des personnes d'âge plus mûr, veillaient au bon déroulement de la partie et comptaient les points. Leur nombre n'était pas fixe. Le ballon, fait de peau de daim, était, en prévision d'une partie, suspendu à l'aide de cordelettes de papier torsadé à une branche du pin ou du saule. La partie commençait par l'envoi de la balle, honneur qui revenait à l'un des joueurs. Le jeu consistait à recevoir et renvoyer la balle, à l'aide exclusivement des pieds, sans la laisser tomber sur le sol : la correction, l'élégance des déplacements sur le terrain, étaient pris en compte pour le calcul des points. On commençait à compter les points après cinquante passes du ballon. Si la partie n'avait pas été interrompue par la chute du ballon (ou la tombée de la nuit), la victoire était attribuée à mille points. Ce jeu, dont la première exécution de l'année pouvait donner lieu à une célébration au début du troisième mois, est illustré de manière très vivante dans le Rouleau enluminé du cycle annuel des célébration." Quoted from: Les plaisirs enchantés : célébration, fêtes jeux et joutes poétiques dans les jardins japonais de l'époque de Heian by Michael Viellard-Baron. |

|

Kensaki |

剣先 けんさき |

Point of a sword and a term describing the shape of a squid. |

|

Kensaku and riken |

羂索 & 利剣

けんさく & りけん |

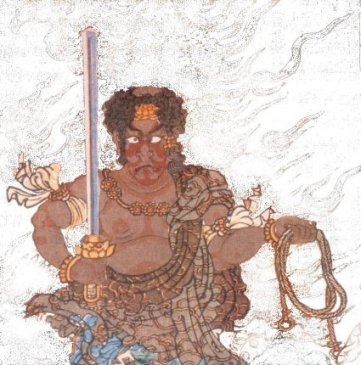

As I have noted before there seems to be a word for just about everything. And so it is with the two items held by Fudō Myōō, one of the five wise kings of Buddhism. He carries a sword referred to as riken with which he will destroys all of the enemies of Buddhist doctrine and the special cord called kensaku with which he lassoes souls worthy of salvation.

The image to the left is a doctored detail from a print by Toyokuni III.

"The noose (pāśa) is the attribute of other Buddhist divinities, most notably the wrathful Acalanatha (Jap. Fudō Myō-ō, 'the Dhāraṇī - King, Immovable'), who embodies the Wisdom that cuts away the passions and the erroneous forms of knowledge that impede the attainment of Enlightenment. He holds the sword of Wisdom in the right hand, with which he severs these hindrances, and in his left he holds the 'binding rope' (Jap. baka no nawa) with which he hobbles the demons of obstruction and draws in beings toward liberation." Quoted from: The Symbolism of the Stupa by Adrian Snodgrass, p. 124. |

|

Kentō |

見当

けんとう

|

The kentō is the registration marks carved on the printing block which allows the accurate alignment of numerous colors using many blocks for a single image. It is made up of two parts: The "L" shaped section called a kagi (鍵 or かぎ); and the "straight-line guide or trait carved on the block at a short distance from..." the kagi called the hikitsuke (溝? or ひきつけ).

The image to the left was provided by David Bull the originator of the Baren Forum. Clearly it does not represent the carved block itself, but rather comes from the printing of the hanshita (see our entry on that term) from that block. A printed image done in this manner obviously reverses the lines of the block. That is, the kagi on the carved block is placed in the lower right hand corner.

After posting the original entry the other day with the print of the little boy in the boat by David Bull our generous contributor E. sent us a fanciful example by Kuniyoshi which distinctly shows the kagi in the lower right. Unfortunately the hikitsuke does not appear on this copy.

Thanks E!

|

|

"Correct register of the various colour-blocks is secured by cutting an angle in the lower right-hand corner of the outline-block, and in the left-hand corner in the same straight line a slot. These two marks are cut in exactly the same place on all the other blocks, and in printing the sheets are imposed in such a way that their lower and right-hand edges fit exactly against these marks. By this simple device perfect adjustment of register is almost invariably secured." Quoted from: A History of Japanese Colour-prints by W. von Seidlitz, p. 14. |

||

|

|

||

|

Ken'yakurei |

儉約令 |

Sumptuary laws: [Think 'sumptuous'] - Laws meant to maintain traditional distinction between classes by regulating the consumption of articles or controlling luxuriant life styles. "They appear to increase in frequency and in minuteness from about the middle of the seventeenth century through the next two centuries of the regime."

Source and quote: 'Sumptuary Regulation and Status in Early Tokugawa Japan’ by Donald H. Shively, Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies, Vol. 25, (1964 - 1965), p. 124.

|

|

It was galling to the upper classes, i.e., samurai and daimyo, to see commoners wearing expensive garments. "The government therefore prescribed that consumption should be correlated precisely with status." (p. 126) There had been an attempt to prohibit embroidery from women's clothes, among other things, but this effort had failed. So, the government decided that only elaborate embroidery should be banned. More warnings were posted. Word was spread that a woman had been jailed for this offense. (p. 127) [One can't help but think of modern attempts being made in Christian and Islamic nations to impose dress codes on their populations.] An account from 1681 states that the shogun noticed that the women from a merchants household were 'over-dressed'. For this effrontery the man's lands and property were confiscated and he was banished. (128)

Shively relates the story of the wives of two wealthy merchants trying to outdo each other. One, a visitor to Kyōto, dazzled the locals with her stunning kimono. Her competitor, a resident of that city, then showed up with a robe embroidered with a pattern of nandina or nanten (南天) leaves. (Also known as heavenly or sacred bamboo.) The visitor would have won this competition until someone noticed that the berries of the nandina were made with real coral. (Ibid.) Note: This story is about the same merchant and his wife who were later banished for thier extravagance.

As early as 1648 Edo townspeople were told that their servants were not to wear silk, at least, not refined silk. In Osaka servants were forbidden from wearing obis made of silk or velvet and the same was true for their loincloths or shita-obi (下帯). "As a garment in which forbidden materials could be worn with the least danger of detection, fancy loincloths were in favor among both men and women throughout the Tokugawa period. In the same year there was another proclamation on this subject: 'The loincloths of sumō wrestlers should not be made of silk. Even when they were invited to the mansions (of samurai) they should wear cotton loincloths". Ibid.

In 1719 new edicts were handed down which banned townspeople from wearing wool capes, household articles with gold lacquer decoarations, 3 story structures, gold or silver leaf in the architectural details, having fancy gear for their horses, elaborate weddings or funerals (p. 130), wearing long swords or large short swords and... (on and on and on.) Actually the list does not go on and on, but it probably felt that way to the commoner residents of Edo. Besides there were other restrictions: No riding in palanquins; no elaborate altar's to the dead with artificial velvet flowers or gilding of any kind using silver or gold. Ibid.

At least townsmen could carry ordinary short swords or wakizashi (脇差), "but long swords were reserved for samurai." Footnote 15, p. 160.

No more than 2 soups or 5 dishes were to be served during festive occasions. (p. 130) At the time of low rice harvests in 1701 the drinking of sake was not even permitted. (Footnote 18, p. 160)

At one point dyers were told not to apply extra wax to heighten a sheen. Buddhist and Shintō priests were urged to dress simply and to tone down ceremonies and processions including the use of elaborate palanquins and umbrellas. (p. 130)

The popular late 17th century author Ihara Saikaku (1642-93: 井原西鶴) noted that many of the sumptuary laws were often ignored. "Even the loincloth for bathing is a double layer of crimson silk dyed in safflower, while the tabi are made of white satin. These are things that in former times even a daimyo's lady did not have." (p. 131)

In the pleasure quarters money trumped class. It was considered unseemly for members of the samurai class to visit such places, but they did so anyway. However, because of the stigma it was important that they not draw attention to themselves and so they dressed down. As a result, imagine their growing resentment the samurai had toward the conspicuous consumption so lavishly exhibited - even flaunted - by wealthy merchants. ¶ Shively Considering the role prostitutes played in society it only makes sense that they would want to present themselves as sumptuously as possible. However, in 1617 prostitutes were proscribed from the use of gold and silver appliqué on their clothing. Osaka proprietors were told "You should not dress prostitutes in kimono with embroidery or appliqué of gold or silver leaf, dapple tie-dyeing, or [woven material with] gold thread in it." Actors were also subject to clothing restrictions: no embroidery, red or purple linings or even purple caps. Shively notes that the wearing of purple was an Imperial Court prerogative. (p. 132) In 1636 the manager of a puppet troupe was jailed for displaying a purple curtain. (p. 133)

Shively hypothesizes that enforcement of sumptuary laws through confiscation may have been based more in greed or relief of a daimyo's debt than in an effort to punish an offender. He also notes that many merchants who were listed as agents of a daimyo, but who lived lavishly went untouched by the authorities. He adds: "The frequency with which laws were reissued suggests that the government relied more on admonition, exhortation, and threat than on actual penalties." (p. 134) Their lack of effectiveness was mocked by the term mikka hatto (三日法度) or 'three-day laws'.

In 1668 the government banned the importation of gold thread, coral, exotic woods, Dutch goods and "...curiosities in general." Later red blankets and woolen materials were added. Food items could not be sold too early or too late: Fresh tree mushrooms in the first month, fern shoots in the third, bamboo shoots in the fourth, eggplants in the fifth, etc. As a host don't even think of serving wild geese or ducks, cranes, swans or water chestnuts. And believe it or not these laws in general became even more detailed in the early 18th century: cakes and books, combs and bodkins; tobacco pouches, purses, incense burners, sake stands. Dolls couldn't exceed 9" and Buddhas were to be kept below 3'. By the middle of the 19th century the rules had reached the absurd as if they were already absurd enough. (p. 135)

Shively points out the it wasn't just the Japanese who imposed such rules and regulations. The French, the English, the Swiss and others had their own and very similar laws. And don't even get me started on the Puritans in Massachusetts. When I was younger Missouri still enforced many of its 'Blue laws'. Almost nothing could be sold on Sunday except for groceries so everyone drove across the state line to Kansas to buy most of what they wanted. Kansas merchants prospered and Missouri merchants suffered piously. ¶ Even the ancient Greeks, Romans and Chinese tried to impose their wills. In fact, the earliest Japanese attempts to control the populace through a dress code were modeled on those of T'ang dynasty China. (p. 136)

"Living in a castle town, the chonin [townsman] was constantly reminded of his mean station. Not only the location and size of his residence were restricted, but in theory his furnishings, food, and clothing were all expected to be scaled accordingly. The whole manner of living was determined by status - such motor habits as the manner of walking, sitting, bowing, even to the way of talking and the vocabulary and verb forms." (p. 143)

Note that some townspeople who were in the direct service of the shogun or a daimyo were permitted to carry two swords as the samurai did. (Ibid.)

The sumptuary laws were not applied to the townspeople exclusively. Every group, from the lowest to the highest, had their restrictions. Often this was an effort to maintain social distinctions, but it was also meant to curb spending and encourage thrift. Even the daimyo and their wives were subjected to these rules. Only so much was to be spent on clothing, gifts, weddings, religious celebrations, etc. Even the size of a lord's retinue was governed by his rank - especially when traveling in processions to and from their home territories or on pilgrimages. "All of these instructions seem to have been rather ineffective." (p. 148) Everyone was ranked and within each rank their were further distinctions between the highest and the lowest. These too had their rules.

Marriages between different daimyo families were held by law in Edo in the 17th century. (p. 149)

Prior to the peaceful times of the Tokugawa era daimyos earned glory on the battlefield. However, as residents of Edo their only glory came from opulence and this pitted one against the other financially. (p. 150) The government was not as concerned with this kind of high level competition because it helped drain the purses of the daimyo and thus kept them weak.

Shively quotes a government statement from 1710: "In clothing and houses, provisions for banquets, and articles of gifts, some are extravagant and others are too frugal. Both of these are at variance with propriety. The superior and inferior should observe their proper station..." (p. 152)

*** "We are inclined to consider sumptuary laws (ken'yakurei) as being entirely negative, a device for repressing the lower orders. Although most of the Tokugawa sumptuary regulations carried the message of not exceeding one's level, it was of equal importance to live up to one's level." (p. 153)

Farmers could not wear silk even if they harvested it. They couldn't wear striped material or pattern dyed cloth. "Purple, crimson, and plum colored dyes were forbidden, but pale yellow, grey, dark blue and persimmon could be worn." If a farmer returned from living in a city he had to redye any inappropriate colors or patterns. "Ordinary farmers were not to wear cotton rain capes or use umbrellas." Etc! Farmers were encouraged to eat grains and not consume the rice they grew. They were not to drink sake or brew it. (p. 154) "Ordinary farmers were not to have floor mats (tatami), paper-covered sliding doors, or verandas." Merchants were generally barred from entering agricultural villages and the list of items which could not be sold to farmers was great. This included a ban on books because keeping a farmer uneducated kept him closer to the land. Farmers were even encouraged to divorce lazy wives. (p. 155) |

||

|

LINKS TO OUR OTHER INDEX/GLOSSARY PAGES Click on any of the pages listed below!

|

||

|

|

The wallpaper on this page is from a photo of flowers my friend Hiroko brought me Thanksgiving 2010 along with some great food.

Hiroko has been a good friend since I moved to Port Townsend. She is bright, talented and fun to talk to. What more could one want in a friend? |

|

HOME

HOME